Low Birth Weight Babies and Disability (2024)

Chapter: Summary

Summary1

Each year in the United States, approximately 3.6 million live births occur, about 10 percent of which are preterm, defined as delivery at less than 37 weeks gestational age. The percentage of infants born with low birth weight (LBW), defined by the medical community as less than 2500 grams (5.5 pounds) at birth, is between 8 and 9 percent, and in 2021 was 8.52 percent. Although survival has improved in all gestational-age categories over the last 20 years, rates of both in-hospital and long-term morbidity do not appear to have improved appreciably. Looking at outcomes, particularly among deliveries at early gestational ages, the risk for disability appears to increase as gestational age increases from 22 to 28 weeks because the survival rate increases. However, disability among survivors decreases throughout this gestational age range: Survival without disability increases from 23 percent at 22 weeks to 71 percent at 27 weeks.

Most infants born preterm or LBW will not be severely impacted by developmental impairments and major or multiple neonatal health conditions. Research dating back as early as the 1990s, however, clearly indicates that these infants experience elevated rates of mild to moderate chronic health conditions, such as cognitive impairment, behavioral impairment, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, autism spectrum disorder, and cerebral palsy, as well as hearing loss, vision loss, chronic lung disease, asthma, and epilepsy—conditions that have meaningful functional impacts into childhood and throughout adolescence. Infants born at older gestational

___________________

1 This summary does not include references. Citations to support the text and conclusions herein are provided in the body of the report.

ages and higher birth weights typically are less frequently and less severely affected than those born at younger gestational ages and lower birth weights.

In August 2022, the Social Security Administration (SSA) requested that the Health and Medicine Division of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine convene an ad hoc committee of relevant experts2 to provide an overview of the current status of the identification, treatment, and prognosis of LBW babies, including trends in survivability, in the U.S. population under age 1 year. The committee was also asked to provide information on short- and long-term functional outcomes associated with LBW, the most common conditions related to LBW, types of services or treatment available, and other considerations. SSA requested that the committee’s report include findings and conclusions, but no recommendations.

STUDY APPROACH AND SCOPE

The committee and National Academies staff conducted an extensive literature search to identify sources pertaining to the epidemiology of LBW, as well as the diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment of disabilities resulting from being born LBW. The search included peer-reviewed scholarly articles from 2002 to 2022, with a focus on the United States, Canada, France, Norway, Sweden, and Denmark. Online databases used in the search include EMBASE, PubMed, ProQuest, and Scopus. Committee members and project staff identified additional relevant literature using traditional academic search methods and online searches. In addition to journal articles, the search included websites of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the World Health Organization, and SSA. The committee also engaged in discussion with a panel of experts who work with families of LBW babies.

Low Birth Weight

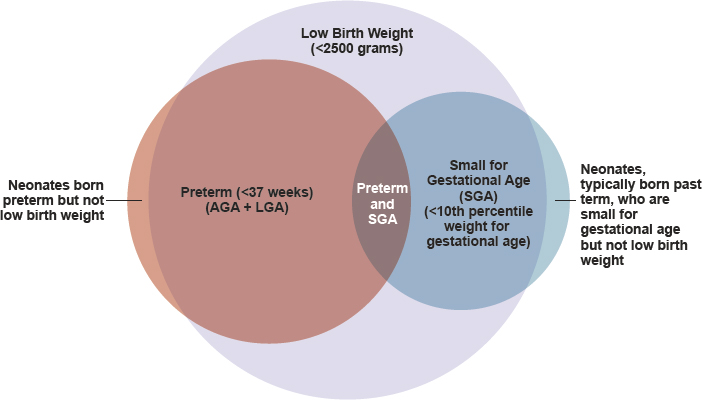

The term “LBW” is typically used to define infants born less than 2500 grams and comprises a heterogenous group of infants that fall into one of three categories: (1) those who are born preterm (as noted above, defined as less than 37 weeks gestational age); (2) those who are small for gestational age (SGA, i.e., weighing below the 10th percentile for gestational age at birth); and (3) those who are born both preterm and SGA (Figure S-1).

The majority of the report addresses infants in this third category, rather than those born SGA at full term. Note that, despite different though

___________________

2 The committee included experts in neonatology, developmental pediatrics, physical medicine and rehabilitation, rehabilitation therapies (occupational, physical, speech-language), psychology and neuropsychology, obstetrics, social determinants of health, statistics/epidemiology, epigenetics, economics, and public policy.

NOTES: AGA = appropriate for gestational age; LGA = large for gestational age. The proportions shown in the figure represent conceptual approximations.

often overlapping definitions, the terms “preterm birth” and “LBW” are often used interchangeably. Note further that, while most of this report employs the medical criteria for LBW, SSA uses different criteria in the weight cutoffs specified in its Listing of Impairments (listings) for LBW, as described below.

Disability and Low Birth Weight

Social Security Administration

The SSA provides means-tested benefits to low-income elderly individuals and those with disabilities or blindness in the United States through the Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program. SSI has covered children aged 0–17 with disabilities since its enactment in 1972. In June 2023, 991,000 children were receiving SSI disability benefits.

In determining a child’s eligibility for SSI, SSA first conducts a means test to determine whether the child is financially eligible for SSI benefits. If the child is determined to be financially eligible, state Disability Determination Services (DDS) assess the child’s impairment and apply SSA criteria to determine whether the impairment constitutes disability. These criteria state that a child under age 18 will be considered disabled if he or she “has a medically determinable physical or mental impairment, which results

in marked and severe functional limitations, and which can be expected to result in death or which has lasted or can be expected to last for a continuous period of not less than 12 months.”3 Once the DDS has established the presence of a severe medically determinable physical or mental impairment(s) that meets the duration requirement, it determines whether that impairment(s) meets, medically equals (is equivalent in severity to), or functionally equals (i.e., results in functional limitations equivalent in severity to) the criteria in SSA’s listings for children. Organized by body system, the listings describe impairments that SSA considers severe enough to cause marked and severe functional limitations in children.

In 1991 SSA defined LBW as a condition “functionally equivalent” to the criteria for a disability listing, meaning that infants born below certain birth weights are automatically classified as medically eligible for SSI. In 2015, LBW became its own medical listing, with the same birth weight criteria defined in 1991. Under listing 100.04A, infants with birth weight under 1200 grams are automatically eligible for SSI. Under listing 100.04B, infants at higher birth weights may be automatically eligible depending on their gestational age (see Table S-1). SSA defines birth weight as the first weight recorded after birth, as documented by an original or certified copy of the infant’s birth certificate or by a medical record signed by a physician.

For most children receiving SSI benefits for disability, SSA conducts periodic Continuing Disability Reviews (CDRs) to determine whether they are still considered to have a disabling condition. For children who qualify for SSI initially on the basis of LBW, CDRs are generally expected to be conducted by age 1 unless, at the time of the initial determination, SSA found that the infant would be expected to remain disabled at age 1.

| Gestational Age | Birth Weight |

|---|---|

| 37–40 weeks | 2000 grams or less |

| 36 weeks | 1875 grams or less |

| 35 weeks | 1700 grams or less |

| 34 weeks | 1500 grams or less |

| 33 weeks | 1325 grams or less |

| 32 weeks | 1250 grams or less |

SOURCE: SSA, 2023.

___________________

3 42 U.S.C. 1382(c).

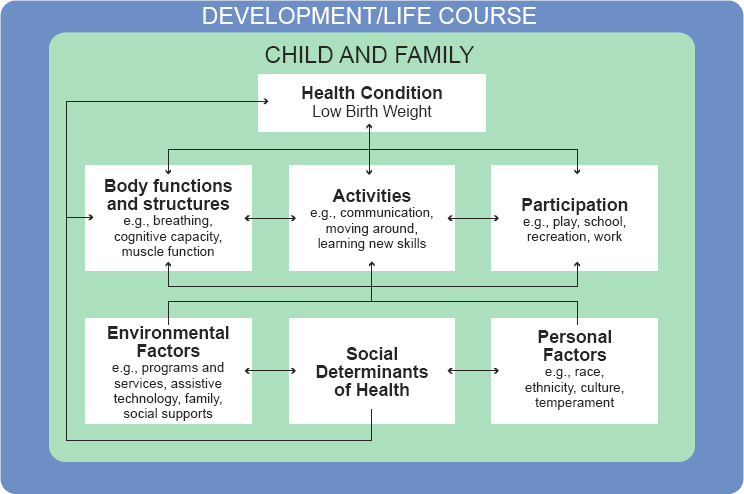

World Health Organization

The World Health Organization’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) and International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: Children & Youth Version (ICF-CY) exemplify a biopsychosocial model of functioning and disability in which disability “denotes the negative aspects of the interaction between an individual (with a health condition) and that individual’s contextual factors (environmental and personal factors)” (WHO, 2007, p. 228). To understand the impact of a health condition such as LBW on children’s health and well-being, one must appreciate a complex set of interacting factors. To guide its work, the committee developed a framework based on the ICF model of functioning and disability (Figure S-2). Because the well-being of children, especially in the first year of life but also throughout childhood and adolescence, is intertwined with the well-being of their caregivers, the committee’s framework is placed within the context of the child and family and is intended to describe the factors that affect this unit.

The impact of LBW, a health condition, can be described in terms of functioning in the three related but separate domains of the ICF-CY model.

SOURCE: Adapted from the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: Children & Youth Version model (WHO, 2007).

The body functions and structures domain describes the impact of LBW on the intactness of the child’s body structures (e.g., lungs, brain) and on physical and psychological functioning (e.g., breathing, cognition, muscle function). LBW also may affect a child’s functioning in the activities domain (e.g., communication, moving around, learning new skills). Functioning in the participation domain describes the child’s engagement in tasks that are part of a culturally important setting (e.g., play; school; recreation; or, later, work). As the arrows in Figure S-2 indicate, relationships among these levels can be bidirectional and either positive or negative. For example, breathing impairments, such as those resulting from asthma, may lead to difficulty with engaging in certain activities, such as sustained vigorous movement. However, learning relevant new skills, such as, in the case of asthma, asthma monitoring, may reduce its severity and the risk of long-term impairment.

The impact of a health condition such as LBW on activity and participation is most likely to be indirect; that is, the health condition gives rise to impairment(s) that in turn may limit the performance of desired or expected activities. Activity limitations, in turn, may give rise to participation restrictions by limiting the child’s ability to perform activities that are expected in a given situation. For example, a limitation in a child’s ability to sustain vigorous physical activity may result in a restriction on their participation in some athletic or playground activities. It should be noted that LBW, while identified as a single health condition in Figure S-2, is an umbrella term for multiple potential health challenges, including physical and mental health, that are associated with preterm birth and/or LBW. Each of these challenges, and the child, family, and environmental responses to them, may lead to consequences in each of the three major ICF domains, and these consequences also are likely to interact with each other. The ICF-CY framework also includes the impact of contextual factors, termed environmental (e.g., programs and services) and personal (e.g., race and ethnicity), on functioning and outcomes in all domains. To these, the committee added social determinants of health, which are recognized as critical for understanding the situation of LBW children. Although some concepts included in social determinants of health overlap with environmental or personal factors, the committee believed that they should be recognized as a separate component because of their importance with respect to LBW.

The multiple bidirectional arrows in Figure S-2 indicate the interactions among the elements depicted, implying a very dynamic process. Another important influence on these interactions is the developmental process and their occurrence in the context of the child’s development and life course, as depicted in the figure. A life-course approach to health and development recognizes that children’s health and well-being and functional capacity evolve over time; that development is continuous over the lifespan; and that development is plastic and sensitive to the timing of exposures to risks, opportunities, and interventions.

Treatment and Services

The committee’s statement of task asks for information about “the types of services or treatment” available to LBW babies. A variety of terms (e.g., “treatments,” “therapies,” “interventions,” “services”) are often used interchangeably in the context of health care, and for this reason, this report does not distinguish between treatments and services. Treatments and services encompass therapeutic agents, therapies, procedures, counseling, and assessments rendered to LBW infants by formally trained professionals with the goal of maximizing growth, health, development, and quality of life through the lifespan.

OVERALL CONCLUSIONS

The committee formulated overall conclusions in the following six areas: (1) morbidity and mortality, (2) developmental trajectories, (3) function and outcomes, (4) treatment and services, (5) social determinants of health, and (6) SSA’s disability criteria and LBW. In addition, most of the report’s chapters end with a set of findings and conclusions based on the evidence presented in those chapters. Many of these chapter-specific findings and conclusions provide the evidentiary support for the committee’s overall conclusions.

Morbidity and Mortality

Although all preterm and LBW neonates have increased rates of short- and long-term morbidity, morbidity is inversely proportional to gestational age. For example, approximately 7 percent of children worldwide who are born prior to 37 weeks gestation will experience long-term neurodevelopmental impairment. The highest risk for morbidity and mortality is among infants born at less than 32 weeks gestation and less than 1500 grams. The risk of impairment among children born preterm increases with birth at earlier gestational ages, with an estimated 24 percent of children born prior to 31 weeks and up to 52 percent of those born prior to 28 weeks showing impairment. Cognitive, motor, behavioral, and functional/school outcomes improve as gestational age increases.

- There is an inverse relationship between gestational age and mortality and health outcomes among infants born preterm, as well as health outcomes among infants born small for gestational age.

- Survivability has increased among preterm newborns over the past two decades. However, increased survivability at earlier gestational ages results in increased short- and long-term morbidities and functional limitations that may require lifelong intervention.

- Among infants born preterm, the risk of long-term impairments and secondary health conditions that adversely affect functioning is more strongly associated with gestational age than with birth weight.

- Children born preterm or LBW may experience a wide range of health conditions, including motor disorders (e.g., cerebral palsy, developmental coordination disorder), sensory disorders (e.g., vision loss, hearing loss), cognitive disorders (e.g., attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, intellectual developmental disorder), social-emotional behavioral disorders (e.g., anxiety, depression), and communication disorders (e.g., autism spectrum disorder).

- With continued improvement in neonatal care, more children will survive at younger gestational ages, and the population of those with morbidities will increase.

Developmental Trajectories

Development refers to an active process that depends on the codevelopment of various physiological and organ systems with experiences and the environment in the context of genetic and epigenetic factors. Developmental skills provide the scaffolding for function. Assuming a typical developmental trajectory, a child’s attainment of skills within the first years of life is rapid and expansive and continues at least into early adulthood. Although there is seldom a one-to-one correspondence between developmental and functional domains, skills in all developmental domains will impact those in all functional domains, especially over time. Disruption of development because of LBW or preterm birth can result in persistent altered developmental trajectories that will impact the degree of functioning and independence attained in adulthood. Development can be disrupted by genetic, medical, environmental, and psychosocial factors, including those identified as social determinants of health.

- Normal development is an active process that depends on the appropriate formation of neural networks and the integrity of physiological systems, as well as a developing child’s physical and psychosocial environments, beginning in utero and continuing after birth.

- Development occurs across multiple domains (i.e., motor, cognition, communication, social-emotional, adaptive).

- Anything that interferes with an environment (internal or external) conducive to optimal development can negatively affect a child’s development, potentially resulting in functional limitations or ongoing health conditions.

- Increasing medical and psychosocial risk factors may have an additive effect on development and function, resulting in increased complexity in the care and intervention needed.

- Infants who are preterm often require intensive and/or extended hospitalization, which significantly limits their ability to function normally in a family unit, impeding normal development and altering growth trajectories.

- Social determinants of health are among the environmental factors that can affect children’s development positively (opportunities) or negatively (barriers).

Function and Outcomes

Preterm or LBW status at birth is associated with significant risk for medical morbidities, social-emotional dysfunction, and various cognitive impairments. Affected children have variable outcomes in these areas related to gestational age and birth weight. Typically, those born at earlier gestational ages (e.g., <32 weeks) and lower birth weights (<1500 grams) are more likely to experience persistent and severe health problems and functional limitations relative to those born at later gestational ages and higher birth weights. Health conditions and impairments associated with preterm birth or LBW can affect every body system and have chronic, lifelong impacts on health, functioning, and well-being. As noted above, although not all children born LBW have significant medical comorbidities, increased survivability at early gestational ages has resulted in a new cohort of children with health conditions of varying severity. In addition, many children born preterm experience multiple medical comorbidities, with a clear additive effect on functional outcomes.

- Children born preterm or LBW have increased risk for associated impairments and health conditions that can have negative sequelae affecting all body systems, with lifelong impacts across all functional domains.

- All functional domains identified in SSA’s disability determination process for children may be affected by the impairments and health conditions associated with preterm birth and LBW.

- The occurrence of multiple medical comorbidities has a negative additive effect on functional outcomes.

- Some developmental problems associated with LBW, particularly those involving higher-order, or advanced, cognitive skills, may not be identified until a later age, when those skills are typically expected to appear.

- Social determinants of health, including socioeconomic status, structural racism, and access to resources, directly influence all outcomes across all medical and neurodevelopmental domains.

Treatment and Services

Children’s skills in all domains, as well as overall functioning, require close monitoring and prompt therapeutic intervention when delays or atypicalities are detected. Developmental outcomes can be improved by early screening and identification, which can lead to early implementation of effective interventions. Evidence increasingly shows that growth, health, and development are impacted by a wide range of medical, educational, and psychosocial determinants. In the past two decades, advances in neonatal care, such as routine use of antenatal steroids and reduced use of postnatal steroids, increased use of noninvasive respiratory support, and sepsis prevention initiatives, have focused on improving outcomes for children born preterm, while maintaining or improving survival. Complementing advances in medical care, hospital-based modifications to environments and specific developmental interventions have been implemented in some neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) to promote optimal neonatal development. Examples of such interventions include implementation of kangaroo care, minimized handling of extremely LBW infants by medical staff, reduced direct lighting, and increased involvement of parents in the day-to-day care of their infants.

The services and treatments currently available for LBW are strongly influenced by the life-course model of care, which emphasizes that interventions at different points in a child’s development have different impacts over time. In general, the earlier and more sustained a service is, the greater is its long-term impact on growth and development for LBW infants. Although research has not always been focused on effectiveness in relation to the age at which therapy starts, interventions provided during the emergence of skills earlier in life, rather than those aimed at modifying already learned behavior later in life, can be expected to lead to better outcomes.

- Appropriate and timely screenings, evaluations, treatments, and services are expected to improve outcomes among children born LBW. There is general consensus that the earlier and more sustained a developmental or educational intervention is, the greater will be its long-term impact on growth, development, and functioning for LBW infants.

- The foundation of development and the acquisition of developmental and functional skills is an active interplay between physiological and anatomical maturation and environmental experience, including parental and family interaction.

- In the past two decades, medical and nonmedical advances in neonatal care have focused on improving outcomes for children born preterm while maintaining or improving survival.

- Guidelines and systems for identifying children in need of intervention have evolved over the past 20 years to include the expectation of routine universal developmental surveillance and screening, referral, and interventions for developmental delays and health conditions, such as hearing loss.

- Barriers to accessing screenings, evaluations, and interventions (e.g., living in underresourced areas, insufficient numbers and distribution of professionals, fragmentation of services, lack of coordination across service sectors) significantly impact outcomes for children born preterm or LBW.

Social Determinants of Health

Social determinants of health have an impact on both maternal and neonatal outcomes, especially among disadvantaged populations. Maternal socioeconomic status is predictive of giving birth to an LBW infant, and family income has a negative and monotonic relationship with infant and maternal mortality. Beyond having fewer economic resources, significant racial and ethnic disparities affect outcomes for LBW infants and their mothers throughout the lifespan. Maternal and infant mortality rates and the likelihood of giving birth to an LBW infant are significantly higher among non-Hispanic Black mothers compared with other racial/ethnic groups. Access to NICUs is a challenge for disadvantaged populations, and social disparities dramatically effect neonatal follow-up, which can impact the health outcomes of LBW infants. Differences in infant mortality rates and outcomes among states are likely due in part to differences in state and local resources for access to prenatal, perinatal, and neonatal care, as well as differences in access to services such as early intervention and NICU follow-up programs.

Although disparities in perinatal and long-term outcomes secondary to social determinants of health are well documented, it can be challenging to quantify them for several reasons, including lack of consensus on how to measure them. In addition, while many studies examine one social determinant of health in isolation, families rarely face only one, making it difficult to interpret results. It also can be difficult to ascertain the ways in which social determinants of health interact and the pathways by which they affect outcomes. Finally, the effects of social determinants of health, such as toxic stress, on outcomes can be cumulative over a person’s life course, adding to the complexity of analysis.

Evidence indicates that targeted policy interventions can ameliorate some of these negative effects of social determinants of health and can reduce the likelihood of LBW birth and other adverse outcomes. For example, a number of social safety net programs involving cash transfers, food

benefits, and refundable tax credits have been shown to reduce LBW births and improve child and family outcomes. The expansion of public health insurance through Medicaid, the establishment of community health centers, and the provision of paid family leave have all been shown to reduce infant mortality. Thus, although social determinants of health have significant impacts on LBW rates and maternal and fetal outcomes, early (pre- and postnatal) interventions can help improve both health and economic outcomes.

- Numerous social determinants of health may have positive or negative effects on outcomes for LBW infants. Targeted interventions can ameliorate the negative effects of social determinants of health and improve outcomes for these infants across all domains.

- The prevalence of preterm birth and LBW, as well as rates of survival and health and developmental outcomes for these infants, may be negatively affected by social determinants of health, including but not limited to unstable and inadequate housing, food insecurity, unsafe neighborhoods, and structural racism.

- Targeted policy interventions, such as cash and food transfers, expanded access to health insurance, and paid family leave, can enhance child and family resiliency and improve outcomes.

SSA’s Disability Criteria and Low Birth Weight

SSI has been shown to improve outcomes for child recipients and their families. However, evidence for positive effects specific to infants eligible for SSI based on the LBW criteria is limited and mixed, indicating the need for additional research. As noted previously, the birth weight cutoffs specified by SSA in the criteria for its LBW listing differ from the current standard criteria used by the medical community. Notably, the 1200 gram criterion for SSI falls between the medical criteria for extremely LBW (<1000 grams) and very LBW (<1500 grams). Among children who are developing at the appropriate weight for gestational age, girls reach 1200 grams between 31 and 32 weeks gestation, while boys do so between 30 and 31 weeks. Birth during this timeframe is considered very preterm. Among children who are large for gestational age, birth weight does not drop below 1200 grams until 27 weeks gestation for girls and 26 weeks for boys. Birth during this timeframe is considered extremely preterm.

Similarly, the listing criteria for birth weight relative to gestational age do not correspond to the percentile cutoffs (3rd or 10th) used by the medical community to identify neonates who are considered small for gestational age. It is important to understand that among infants defined by the medical community as LBW (i.e., <2500 grams), only 16 percent, based

on birth certificate data from 2021, would automatically medically qualify for SSI based solely on SSA’s LBW listing criteria. Even among infants born very LBW (i.e., 1000 to <1500 grams), about 50 percent would not have met the SSA’s current LBW listing criteria even if they met the financial criteria for eligibility.

- The current criteria in the LBW listing in SSA’s Listing of Impairments do not consistently correspond to the current and standard medical definitions of LBW, preterm birth, or small for gestational age (SGA) neonates. Criteria based on birth weight do not take into account that gestational age is a better predictor of short- and long-term outcomes among infants born preterm.

- Among preterm infants, gestational age is a better predictor than birth weight of both short- and long-term outcomes.

- A birth weight of less than 1500 grams is considered very LBW and is close to the 50th percentile for weight at 32 weeks gestation. A birth weight of 1500 grams better corresponds to a gestational age of 32 weeks, after which the risk of severe impairments decreases.

- Infants born SGA (i.e., below the 10th percentile for gestational age) are at increased risk of having medical morbidities and developmental delays associated with poor growth of the brain and body. SGA is an important category of LBW infants born after 32 weeks gestation because their physiology and outcomes are comparable to those of appropriate weight infants who are born earlier.

- Persistent medical and neurodevelopmental conditions associated with LBW can provide alternative diagnoses or listings by which infants allowed disability benefits under the LBW listing may continue to qualify for benefits following a Continuing Disability Review.