Low Birth Weight Babies and Disability (2024)

Chapter: 1 Introduction

1

Introduction

The Social Security Administration (SSA) provides means-tested benefits to low-income elderly individuals and those with disabilities or blindness in the United States through the Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program. SSI has covered children aged 0−17 with disabilities since its enactment in 1972, and while the program initially served few children, the number of children receiving SSI benefits grew rapidly in the 1990s and 2000s, reaching a peak of 1.3 million in 2013 (SSA, 2014). In June 2023, 991,000 children were receiving SSI (SSA, 2023b).

The maximum monthly individual SSI benefit in 2023 is $914 (SSA, 2023c). Child SSI benefits are an important source of income for the families of beneficiaries (on average making up 45 percent of income (Rupp, 2005). As a result, participation in SSI has been shown to reduce family poverty (Duggan and Kearney, 2007).

CONTEXT FOR THIS STUDY

In determining children’s eligibility for SSI, SSA first conducts a means test to determine whether they are financially eligible for benefits. If a child lives with parent(s), a portion of parental income is considered available to the child and will affect eligibility for benefits. If the child is currently in a medical treatment facility, parental income is not considered, but benefit amounts are limited to $30 per month. If the child is determined to be financially eligible, state Disability Determination Services (DDS) assess the child’s impairment and apply SSA criteria to determine whether the

| Gestational Age | Birth Weight |

|---|---|

| 37–40 weeks | 2000 grams or less |

| 36 weeks | 1875 grams or less |

| 35 weeks | 1700 grams or less |

| 34 weeks | 1500 grams or less |

| 33 weeks | 1325 grams or less |

| 32 weeks | 1250 grams or less |

SOURCE: SSA, 2023a.

impairment constitutes disability. These criteria state that a child under age 18 will be considered disabled if he or she “has a medically determinable physical or mental impairment, which results in marked and severe functional limitations, and which can be expected to result in death or which has lasted or can be expected to last for a continuous period of not less than 12 months.”1 Once the DDS has established the presence of a severe medically determinable physical or mental impairment(s) that meets the duration requirement, it determines whether that impairment(s) meets, medically equals (is equivalent in severity to), or functionally equals (i.e., results in functional limitations equivalent in severity to) the criteria in SSA’s Listing of Impairments (listings) for children. Organized by body system, the listings describe impairments that SSA considers severe enough to cause marked and severe functional limitations in children.

Based in part on concerns that low birth weight (LBW) might be linked to a greater likelihood of long-term disability, in 1991 SSA defined LBW as a condition “functionally equivalent” to the criteria for a disability listing, meaning that infants born below certain birth weight cutoffs are automatically classified as medically eligible for SSI (SSA, 1991). In 2015, LBW became its own medical listing, with the same birth weight criteria defined in 1991 (SSA, 2015). Under listing 100.04A, infants with birth weight under 1200 grams are automatically eligible for SSI. Under listing 100.04B, infants at higher birth weights may be automatically eligible depending on their gestational age (see Table 1-1). SSA defines birth weight as the first weight recorded after birth, as documented by an original or certified copy of the infant’s birth certificate or by a medical record signed by a physician.

___________________

1 42 U.S.C. 1382(c).

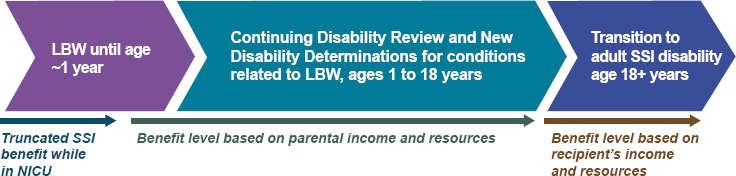

For most children receiving SSI benefits for disability, SSA conducts periodic Continuing Disability Reviews (CDRs) to determine whether they are still considered to have a disabling condition. For children, SSA is supposed to conduct a CDR at least once every 3 years for conditions that are expected to improve. For children whose initial qualifying diagnosis is based on LBW, CDRs are generally scheduled to be conducted by age 1 unless, at the time of the initial determination, SSA found that the infant would be expected to remain disabled at age 1. Hemmeter and Bailey (2015) found that between 1998 and 2008, CDRs led to cessation of eligibility for almost half of LBW SSI recipients. Within 10 years of cessation, 9.4 percent of former LBW recipients had returned to the SSI rolls, and half of these recipients had returned within the first 4 years after cessation. SSA also conducts a redetermination of eligibility based on the adult SSI disability determination process when child SSI recipients turn age 18. Hemmeter and Bailey (2015) show that between 1998 and 2008, eligibility was ceased in 34 percent of age 18 redeterminations. Rates of return to SSI among those whose eligibility was ceased at age 18 depend on the duration of receipt in childhood. Of those children receiving benefits for less than 2 years, 22 percent had returned to SSI within 10 years of age 18 eligibility cessation, compared with only 13 percent of those receiving benefits for more than 6 years as children.

Figure 1-1 illustrates the relationship between the SSA disability processes for children born LBW, and the ages at which they occur and transition points within the developmental timeline. Most notable are the reassessment at or around age 12 months of children who originally qualified for SSI benefits based on the LBW listing criteria, and the reassessment at age 18 of those still receiving benefits to determine whether they continue to qualify under the adult criteria.

STUDY CHARGE AND SCOPE

In 2022, SSA requested that the Health and Medicine Division of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine convene an ad hoc committee of relevant experts to provide an overview of the current status of the identification, treatment, and prognosis of LBW babies, including trends in survivability, in the U.S. population under age 1 year. Accordingly, the 15-member committee included experts in neonatology, developmental pediatrics, physical medicine and rehabilitation,

occupational therapy, physical therapy, speech-language pathology, psychology and neuropsychology, obstetrics and gynecology, social determinants of health, statistics/epidemiology, epigenetics, economics, and public policy (see Appendix C for biographical sketches of the committee members). The committee was also asked to provide information on short- and long-term functional outcomes associated with LBW, the most common conditions related to LBW, types of services or treatment available, and other considerations (see Box 1-1 for the committee’s statement of task).

SSA also specified that, while the listing section that includes LBW also addresses failure to thrive and the study might touch on that topic, the focus of the study would be on LBW babies.

STUDY APPROACH

The Concept of Disability and Low Birth Weight

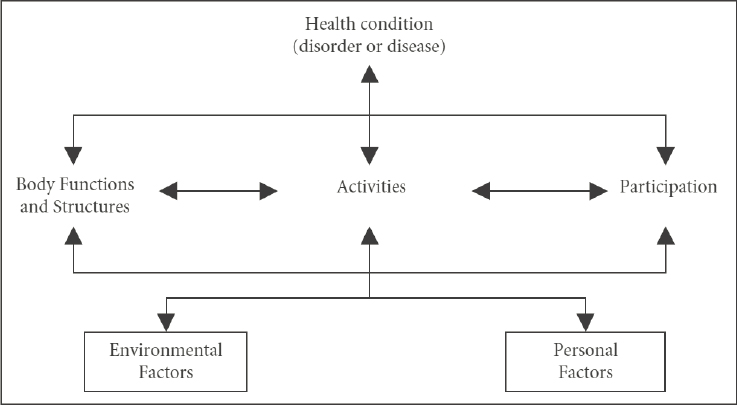

The World Health Organization’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) and International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: Children & Youth Version (ICF-CY) exemplify a biopsychosocial model of functioning and disability (Figure 1-2) in which disability “denotes the negative aspects of the interaction between an individual (with a health condition) and that individual’s contextual factors (environmental and personal factors)” (WHO, 2007, p. 228).

The ICF model captures functioning in three domains (shown in the middle tier of Figure 1-2): (1) body functions and structures, which encompass the physiological functions of the body, including psychological functions, and the functioning of body structures (e.g., movement of limbs, cardiac function); (2) activities, which involve the execution of actions or tasks (e.g., running, problem solving); and (3) participation, which is involvement of an individual in life situations (e.g., participation in school or organized sports) (WHO, 2007, p. 9). The ICF model refers to deficits in body functions and structures as impairments, deficits in executing activities as limitations, and reductions in participation as restrictions (WHO, 2007, p. 9).

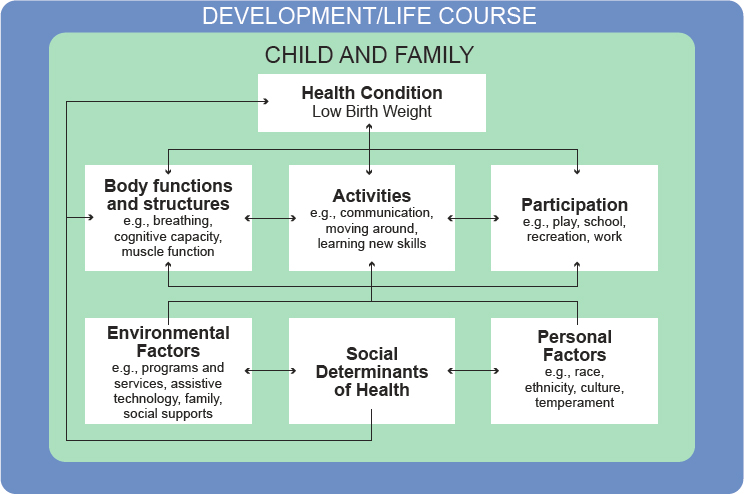

To understand the impact of a health condition such as LBW on children’s health and well-being, one must appreciate a complex set of interacting factors. To guide its work as it considered the evidence to address the questions outlined in the statement of task, the committee developed a framework based on the ICF model of functioning and disability (Figure 1-3). Because the well-being of children, especially in the first year of life but also throughout childhood and adolescence, is intertwined with the well-being of their caregivers, the committee’s framework is placed within the context of the child and family and is intended to describe the factors that affect this unit.

The impact of LBW, a health condition, can be described in terms of functioning in the three related but separate domains of the ICF-CY model. The body functions and structures domain describes the impact of LBW on the intactness of the child’s body structures (e.g., lungs, brain) and on physical and psychological functioning (e.g., breathing, cognition, muscle function). LBW also may affect a child’s functioning in the activities domain

SOURCE: WHO, 2007, p. 17.

SOURCE: Adapted from the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: Children & Youth Version model, WHO, 2007.

(e.g., communication, moving around, learning new skills). Functioning in the participation domain describes the child’s engagement in tasks that are part of a culturally important setting (e.g., play; school; recreation; or, later, work). As the arrows in Figure 1-3 indicate, relationships among these levels can be bidirectional and either positive or negative. For example, breathing impairments, such as those resulting from asthma, may lead to difficulty with engaging in certain activities, such as sustained vigorous movement. However, learning relevant new skills, such as, in the case of asthma, asthma monitoring, may reduce the impairment’s severity and the risk of long-term impairment.

The conceptual model recognizes that the impact of a health condition such as LBW on activity and participation is most likely to be indirect; that is, the health condition gives rise to impairment(s), which in turn may limit the performance of desired or expected activities. Activity limitations, in turn, may give rise to participation restrictions by limiting the child’s ability to perform activities that are expected in a given situation. For example, children’s limited ability to sustain vigorous physical activity may result in a restriction on their participation in some athletic or playground activities. It is important to keep in mind that LBW, while identified as a single health condition in Figure 1-3, is an umbrella term for multiple potential health challenges, including physical and mental health, that are associated with preterm birth and/or LBW. Each of these challenges, and the child, family, and environmental responses to them, may lead to consequences in each of the three major ICF domains, as described in later sections of this report. These consequences also are likely to interact with each other. Thus, for example, the activity limitations and participation restrictions experienced by a preschool child born LBW who has pulmonary and cognitive impairments will likely differ from those of a child with a similar birth history who has been diagnosed with cognitive and mobility impairments.

The ICF-CY framework also includes the impact of contextual factors—termed environmental and personal factors—on functioning and outcomes in all domains. Environmental factors include physical supports, such as assistive technology, that may support the performance of certain activities and more successful participation, but also include the provision of programs and services to the child and family, which may affect all three domains of function. Personal factors include children’s characteristics, such as motivation, persistence, and interests, that may influence how they respond to challenges and opportunities, as well as characteristics, such as ethnicity or gender, that may affect how others in their environment respond to them. The committee included a third contextual factor that more recently has been recognized as critical for understanding the situation of LBW children —social determinants of health (SDOH), described below. It must be noted that the factors included in each of these three domains often interact with

each other and that some aspects of SDOH may also be included in the ICF classification of environmental factors. For example, resources associated with the socioeconomic status of a child’s parents could be included in the figure as an environmental factor as well as one of the SDOH. Similarly, race/ethnicity is a personal factor that has been associated with SDOH. Despite the overlap between the concepts included in SDOH and those included in the ICF environmental and personal factors, the committee believed that the impact of this set of factors on health should be recognized as a separate component. These three sets of contextual factors also may have bidirectional relationships with each other. In addition, SDOH may contribute to the origin of a health condition by increasing the mother’s risk for preterm birth or a baby who is small for gestational age (SGA).

Although the arrows in Figure 1-3 depicting the multiple interactions among the elements of the figure imply a very dynamic process, another important influence must also be recognized: the occurrence of these interactions in the context of the child’s development and life course, as depicted in the figure. A life-course approach to health and development recognizes that children’s health and well-being and functional capacity evolve over time; that development is continuous over the lifespan; and that development is plastic and sensitive to the timing of exposures to risks, opportunities, and interventions. An increasing body of knowledge shows that many factors influence health and development outcomes before and after a child is born. For example, genetics and prenatal factors (e.g., maternal weight and nutrition), birth weight (low and high), and postnatal growth patterns appear to contribute to cardiometabolic risk factors later in life (Kumaran et al., 2017; Lurbe and Ingelfinger, 2021). Appropriate interventions during various developmental stages in response to an identified health risk (e.g., cardiometabolic risk) or developmental condition (e.g., cerebral palsy [CP]) can mitigate risk and reduce the impact of morbidities (Daniels et al., 2011; Jackman et al., 2022; Morgan et al., 2021). As a general rule, the earlier the intervention, the greater is its long-term impact. Thus from a life-course perspective, outcomes for the child and family reflect not only what the needs are and what is provided to address them, but also when (Hagan et al., 2017; Halfon and Forrest, 2018).

A life-course approach to health and development is fundamental to understanding how treatments and services may impact long-term prognosis and impairment for LBW infants. The plasticity of human development means that outcomes can potentially be impacted by early identification of risk factors and timely access to services, particularly at the time when they could have the most impact. Furthermore, early experiences supporting health, development, and well-being can protect against or mitigate future disease, including adult-onset conditions. The timing of significant

developmental progress in one area or domain, such as growth in speech and language abilities, may also greatly affect functioning in other domains, such as performing activities relevant to learning or engaging with peers. The complexity of developmental pathways and the influence of SDOH demand taking a holistic biopsychosocial approach to address the impact of LBW on child impairment, functioning, and prognosis (Hagan et al., 2017; Halfon and Forrest, 2018).

Social Determinants of Health

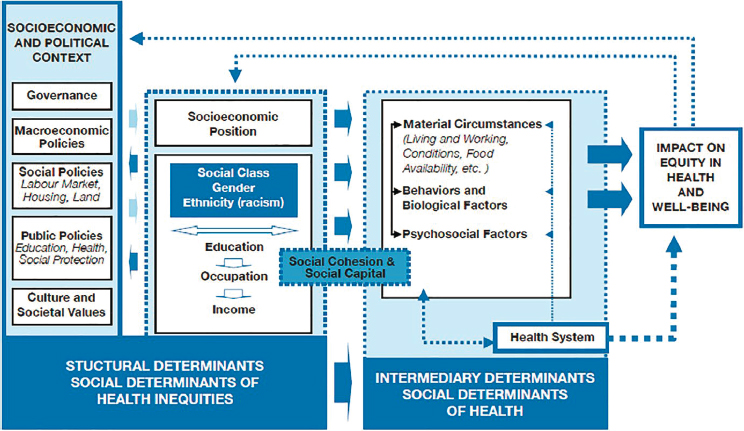

SDOH are the conditions in which people live that affect their health, functioning, and quality of life with respect to both risks and outcomes. SDOH can be grouped into the areas of economic stability (e.g., income, housing, food security); education access and quality; health care access and quality; neighborhood and built environment (e.g., safe housing, clean air and water); and social and community (e.g., social and community supports) (HHS, 2023). The conceptualization of SDOH as they pertain to LBW and neonatal outcomes continues to evolve, and includes such factors as maternal health conditions (e.g., gestational diabetes), childcare availability, and maternal work status. Figure 1-4 illustrates the complex interplay of social, economic, and political factors affecting SDOH and health disparities.

SOURCE: Solar and Irwin, 2010, p. 6.

Although minoritized race has been associated with adverse health outcomes, it must be remembered that race is not a biological factor, but a created sociopolitical construct that has been dynamic throughout history based on societal context. Accordingly, race must be considered not as a determinative variable in and of itself, but as a proxy for environmental and social factors that disproportionately affect these groups, including structural racism (Bailey et al., 2017; Krieger, 2014),2 various environmental exposures, and difficulties with health care access. It is essential that interventions be developed thoughtfully and with consideration of the larger influences informing racial differences (Borrell et al., 2021; Boyd et al., 2020; Roberts, 2023).

Ableism (i.e., bias or discrimination against people with disabilities) and structural ableism contribute to health disparities and barriers to activities and participation among people with physical and mental impairments. People with disabilities experience disparities in health outcomes and access to health care either directly through differential treatment within the health care system or through negative effects on education, employment, housing, and other SDOH (CDC, 2023; Dorsey Holliman et al., 2023; Iezzoni, 2011; Krahn et al., 2015; Valdez and Swenor, 2023). Children and adults with mobility and other physical impairments, including but not limited to CP and vision and hearing impairments, report barriers to participation in the built environment and “ableist attitudes” in the United States and other countries (Anaby et al., 2013; Reber et al., 2022; Smith et al., 2021). Similarly, a scoping review of participation in leisure activities among children and youth with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) found that out-of-school activities among children and youth with ASD take place mainly at home, alone or among family or with other adults. Barriers to participation include negative social attitudes, lack of support from family members and service providers, and lack of available programs (Anaby et al., 2013; Askari et al., 2015).

SDOH have an impact on both maternal and neonatal outcomes, especially among disadvantaged populations. Maternal socioeconomic status is predictive of giving birth to an LBW infant (Mahmoodi et al., 2013), and family income has a negative and monotonic relationship with infant and maternal mortality (Kennedy-Moulton et al., 2022). In addition, significant racial disparities affect outcomes for LBW infants and their mothers

___________________

2 “Structural racism refers to ‘the totality of ways in which societies foster [racial] discrimination, via mutually reinforcing [inequitable] systems . . . (e.g., in housing, education, employment, earnings, benefits, credit, media, health care, criminal justice, etc.) that in turn reinforce discriminatory beliefs, values, and distribution of resources’ [Krieger, 2014], reflected in history, culture, and interconnected institutions” (Bailey et al., 2017).

throughout their lifetime beyond those associated with having fewer economic resources.

Maternal and infant mortality rates are significantly higher among non-Hispanic Black mothers compared with other racial/ethnic groups (Ely and Driscoll, 2023; Hoyert, 2023). In 2021, the mortality rate for non-Hispanic Black mothers was 69.9/100,000 live births, compared with 26.6 and 28.0 for non-Hispanic White and Hispanic mothers, respectively (Hoyert, 2023). The infant mortality rates in 2021 were 10.55/1,000 live births for Black mothers, compared with 4.36 and 4.79 for White and Hispanic mothers, respectively (Ely and Driscoll, 2023). In addition, this population is almost twice as likely as White mothers to give birth to an LBW infant (Almeida et al., 2018). In California, the maternal and infant mortality rates for Black mothers and infants at the top of the income distribution are about 60 percent and 10 percent higher, respectively, than those for White mothers and infants at the bottom of the income distribution (Kennedy-Moulton et al., 2022). Access to neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) is a challenge for disadvantaged populations, and Black and Hispanic mothers with LBW infants in NICU settings are more likely than their White counterparts to experience high levels of chronic stress and to receive inadequate care (Glazer et al., 2021; Profit et al., 2017; Sigurdson et al., 2019). Even after being discharged from the NICU, high-risk infants typically require intense follow-up care. Social disparities dramatically affect neonatal follow-up, which can impact the health outcomes of LBW infants (Johnson et al., 2023).

SDOH, including but not limited to unstable and inadequate housing, food insecurity, unsafe neighborhoods, and structural racism, adversely affect the prevalence of preterm and LBW births, as well as rates of survival and health and developmental outcomes for these infants (Adappa and Barr, 2023; Hong et al., 2021; Johnson et al., 2023; Lorch and Enlow, 2016). Although disparities in perinatal and long-term outcomes secondary to SDOH are well documented, it can be challenging to quantify them for a number of reasons. First, many SDOH have been identified in the literature, but there is little consensus on how to measure them (Elias et al., 2019). Second, many studies examine one SDOH in isolation, but families rarely face only one, making it difficult to interpret results. In addition, it can be difficult to ascertain the ways in which SDOH interact, as well as the specific pathways by which they affect outcomes (Lorch and Enlow, 2016; Penman-Aguilar et al., 2016). Finally, the effects of SDOH, such as toxic stress, on outcomes can be cumulative over a mother’s life course, so that analysis would require using longitudinal data linking maternal experiences and infant outcomes, adding to the complexity of the analysis (Lorch and Enlow, 2016).

Evidence indicates that targeted policy interventions aimed at low-income families can reduce the likelihood of LBW and other adverse birth

outcomes. For example, a number of social safety net programs have been shown to reduce the incidence of LBW, including cash transfers through Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) (Currie and Cole, 1993); food assistance through Food Stamps (the previous name of today’s Special Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program [SNAP]) and the Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) (Hoynes et al., 2011, 2016); and refundable tax credits through the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) (Hoynes et al., 2015). In addition, the expansion of public health insurance through Medicaid (Currie and Gruber, 1996; Goodman-Bacon, 2018), the establishment of community health centers (Kose et al., 2022), and paid family leave programs (Montoya-Williams et al., 2020; Stearns, 2015) have all been shown to reduce infant mortality. Thus, although SDOH have significant impacts on LBW rates and maternal and fetal outcomes, early (pre- and postnatal) interventions can help improve both health and economic outcomes (Adappa and Barr, 2023; Hong et al., 2021; Lorch and Enlow, 2016).

Definitions Relevant to the Statement of Task

The definitions included here highlight the way in which certain terms from the statement of task are conceptualized and used throughout this report unless otherwise noted. These definitions are also captured in Appendix B, along with the definitions of other terms used in the report.

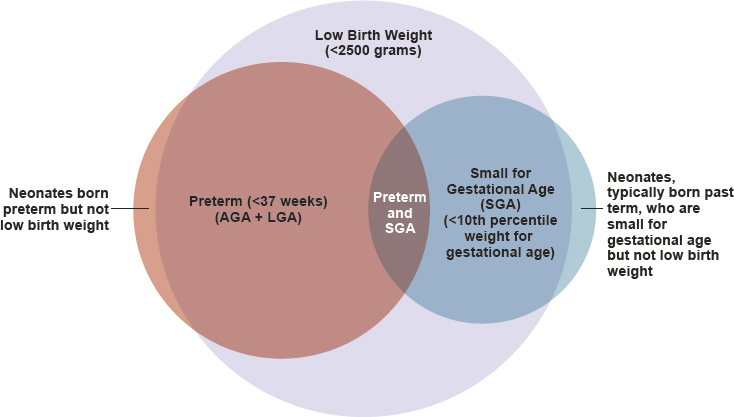

Low Birth Weight

The statement of task asks the committee to address a variety of topics pertaining to “low birth weight,” which is defined by the medical community as less than 2500 grams (5.5 pounds) at birth (WHO, 2015). The term “LBW” refers to a heterogenous group of infants that fall into one of three categories: (1) those who are born preterm (i.e., less than 37 weeks gestational age), (2) those who are SGA (i.e., weighing below the 10th percentile for gestational age at birth), and (3) those who are born both preterm and SGA (see Figure 1-5). Note that, despite different though often overlapping definitions, the terms “preterm birth” and “LBW” are often used interchangeably; most, but not all, preterm infants are also LBW. The sliver on the far left of Figure 1-5 depicts neonates born preterm but weighing 2500 grams or more. Preterm delivery is the leading driver of morbidity, mortality, and the developmental trajectory of LBW infants (Saigal and Doyle, 2008). An additional driver of morbidity and mortality is the growth status of the fetus and infant. Infants born SGA represent about 11 percent of all infants by gestational age (Jensen et al., 2019). Although most infants born SGA are also LBW, some full-term infants are SGA but not LBW. The

NOTES: AGA = appropriate for gestational age; LGA = large for gestational age. The proportions shown in the figure represent conceptual approximations.

sliver on the far right of Figure 1-5 depicts neonates born SGA but weighing 2500 grams or more.

Understanding that LBW comprises the three categories of infants born preterm, SGA, or both is important because the implications differ for each group. Infants born preterm, while LBW, often are the appropriate weight (i.e., in the 10th to 90th3 percentile), or even large (i.e., greater than the 90th percentile), for their gestational age. In the case of preterm LBW infants, treatments, associated secondary health conditions, and outcomes are driven more by gestational age at birth than by the infant’s weight at birth. In the case of infants who are SGA, some are small for nonpathologic reasons having to do with genetics (e.g., small parents). In other cases, SGA is associated with different etiologies, leading to differences from preterm birth in secondary health conditions, treatments, and outcomes. LBW infants also may be both preterm and SGA and at risk for the challenges associated with both groups. The majority of this report addresses infants born preterm and LBW, rather than those born SGA at full term.

The medical categories of LBW and preterm birth are broken down into subcategories with specific definitions. Although some literature defines or subcategorizes SGA using cutoffs of the 3rd or 5th percentiles for weight

___________________

3 The percentile was corrected after initial release of the report.

or length for gestational age (Saenger et al., 2007), the 10th percentile cutoff is most common. Box 1-2 provides the medical definitions for each of the LBW categories and subcategories.

It is essential to note that the birth weight cutoffs specified by SSA in the listing criteria (i.e., less than 1200 grams at birth or the birth weights relative to gestational age listed in Table 1-1) differ from the definitions currently used by the medical community. Notably, the 1200 gram criterion for SSI falls between the medical criteria for extremely LBW (less than 1000 grams) and very LBW (less than 1500 grams). Among children who

are developing at the appropriate weight for gestational age, girls reach 1200 grams between 31 and 32 weeks gestation, while boys do so between 30 and 31 weeks (Fenton and Kim, 2013). Birth during this timeframe is considered very preterm. Among children who are large for gestational age, birth weight does not drop below 1200 grams until 27 weeks for girls and 26 weeks gestation for boys (Fenton and Kim, 2013). Birth during this timeframe is considered extremely preterm. Similarly, the criteria for birth weight relative to gestational age shown in Table 1-1 do not correspond to the percentile cutoffs (3rd or 10th) used by the medical community to identify neonates who are considered SGA (Fenton and Kim, 2013).

Of the 3.7 million live births in 2021, 312,033 were LBW as defined by the medical community (i.e., <2500 grams) based on raw birth certificate data for 2021. Using those data, Table 1-2 shows, for each group encompassed by the medical definitions of LBW, how many infants would have been considered eligible for SSI in that year based solely on whether their birth weight met SSA’s LBW listing criteria. It is important to understand that, whereas most of this report focuses on LBW as defined by the medical community, SSA would consider only 16 percent of those infants as meeting the LBW listing criteria for SSI disability benefits, and fewer than 50 percent

| Medical Criteria | Eligible Based on 1200 gram Cutoff in Low Birth Weight Listing (%) | Eligible Based on Cutoffs for Birth Weight Relative to Gestational Age (%) | Total Eligible Based on SSI Listing Criteria for Low Birth Weight (%) | Ineligible Based on SSI Listing Criteria for Low Birth Weight (%) | Total in LBW Group/s |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extremely low birth weight (<1000 g) | 23,114 (100) | 0 | 23,114 (100) | 0 | 23,114 |

| Very low birth weight only (1000 g to <1500 g) | 9,152 (33) | 4,370 (16) | 13,522 (49) | 13,895 (51) | 27,417 |

| Low birth weight (1500 g to <2500 g) | 0 | 14,431 (6) | 14,431 (6) | 247,071 (94) | 261,502 |

| Total | 32,266 (10) | 18,801 (6) | 51,067 (16) | 260,966 (84) | 312,033 |

SOURCE: Committee tabulations of National Center for Health Statistics’ Natality Public Use File, 2021.

of infants born very LBW (1000 to <1500 grams) would meet the current criteria even if they met the financial criteria.

Treatments and Services

Section 4 of the statement of task asks about “the types of services or treatment” available to LBW babies. Because a variety of terms (e.g., “treatments,” “therapies,” “interventions,” “services”) are often used interchangeably in the context of health care, this report does not distinguish between treatments and services. The goal of treatments and services for LBW infants is to maximize growth, health, development, and quality of life through the lifespan. Treatments and services include therapeutic agents, therapies, procedures, counseling, and assessments rendered by formally trained professionals.

Information Gathering

The committee and National Academies staff conducted an extensive literature search to identify sources pertaining to the diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment of disabilities resulting from being born LBW. The search included peer-reviewed scholarly articles from 2002 to 2022, with a focus on the United States, Canada, France, Norway, Sweden, and Denmark. Online databases used in the search include EMBASE, PubMed, ProQuest, and Scopus. In addition to journal articles, the search included websites of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the World Health Organization, and SSA. Throughout the course of the study, committee members and staff identified additional relevant literature through targeted online searches.

Over the course of the study, the committee met a total of six times—three virtually and three in-person/hybrid. The meetings included two public sessions during which invited experts presented pertinent information regarding LBW babies. The first public session was dedicated to informing the committee about the processes related to LBW within SSA and the SSI program. The second public session included a panel discussion on working with families of LBW infants. Experts included law professionals, a neonatologist, and a pediatrician (see Appendix A). In addition, several National Academies reports informed the committee’s work, including Speech and Language Disorders in Children (NASEM, 2016), Mental Disorders and Disabilities among Low-Income Children (NASEM, 2015), Opportunities for Improving Programs and Services for Children with Disabilities (NASEM, 2018), and Childhood Cancer and Functional Impacts across the Care Continuum (NASEM, 2021).

REPORT ORGANIZATION

Chapter 2 reviews the medical standards for defining LBW and premature infants, current survivability trends, and advances in treatment over the last 20 years. Chapter 3 addresses typical developmental timelines and milestones within the first 2 years of life and the altered trajectories of children born LBW, preterm, and SGA. Chapter 4 provides an overview of selected health conditions and impairments that may affect infants born LBW. Chapter 5 presents a roadmap of available treatments and services. Finally, Chapter 6 contains the committee’s overall conclusions and summarizes the findings on which they are based.

REFERENCES

Adappa, R., and S. Barr. 2023. Social determinants of health and the neonate in the neonatal intensive care. Paediatrics and Child Health 33(6):154–157.

Almeida, J., L. Bécares, K. Erbetta, V. R. Bettegowda, and I. B. Ahluwalia. 2018. Racial/ethnic inequities in low birth weight and preterm birth: The role of multiple forms of stress. Maternal and Child Health Journal 22(8):1154–1163.

Anaby, D., C. Hand, L. Bradley, B. DiRezze, M. Forhan, A. DiGiacomo, and M. Law. 2013. The effect of the environment on participation of children and youth with disabilities: A scoping review. Disability and Rehabilitation 35(19):1589–1598.

Askari, S., D. Anaby, M. Bergthorson, A. Majnemer, M. Elsabbagh, and L. Zwaigenbaum. 2015. Participation of children and youth with autism spectrum disorder: A scoping review. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 2(1):103–114.

Bailey, Z. D., N. Krieger, M. Agénor, J. Graves, N. Linos, and M. T. Bassett. 2017. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: Evidence and interventions. The Lancet 389(10077):1453–1463.

Borrell, L. N., J. R. Elhawary, E. Fuentes-Afflick, J. Witonsky, N. Bhakta, A. H. Wu, K. BibbinsDomingo, J. R. Rodríguez-Santana, M. A. Lenoir, and J. R. Gavin III. 2021. Race and genetic ancestry in medicine—A time for reckoning with racism. The New England Journal of Medicine 384(5):474–480.

Boyd, R. W., E. G. Lindo, L. D. Weeks, and M. R. McLemore. 2020. On racism: A new standard for publishing on racial health inequities. Health Affairs Forefront. https://doi.org/10.1377/forefront.20200630.939347.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2023. Disability impacts all of us. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/disabilityandhealth/infographic-disability-impacts-all.html (accessed September 26, 2023).

Currie, J., and N. Cole. 1993. Welfare and child health: The link between AFDC participation and birth weight. American Economic Review 83(4):971–985.

Currie, J., and J. Gruber. 1996. Saving babies: The efficacy and cost of recent changes in the Medicaid eligibility of pregnant women. Journal of Political Economy 104(6):1263–1296.

Daniels, S. R., C. A. Pratt, and L. L. Hayman. 2011. Reduction of risk for cardiovascular disease in children and adolescents. Circulation 124(15):1673–1686.

De Pietro, M. 2023. What is the average baby weight by month? Medical News Today. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/325630 (accessed July 20, 2023).

Dorsey Holliman, B., M. Stransky, N. Dieujuste, and M. Morris. 2023. Disability doesn’t discriminate: Health inequities at the intersection of race and disability. Frontiers in Rehabilitation Sciences 4:e1075775.

Duggan, M. G., and M. S. Kearney. 2007. The impact of child SSI enrollment on household outcomes. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 26(4):861–885.

Elias, R. R., D. P. Jutte, and A. Moore. 2019. Exploring consensus across sectors for measuring the social determinants of health. SSM Population Health 7:e100395.

Ely, D. M., and A. K. Driscoll. 2023. Infant mortality in the United States, 2021: Data from the period linked birth/infant death file. National Vital Statistics Reports 72(11):1–19.

Fenton, T. R., and J. H. Kim. 2013. A systematic review and meta-analysis to revise the Fenton growth chart for preterm infants. BMC Pediatrics 13:59.

Glazer, K. B., S. Sofaer, A. Balbierz, E. Wang, and E. Howell. 2021. Perinatal care experiences among racially and ethnically diverse mothers whose infants required a NICU stay. Journal of Perinatology 41(3):413–421.

Goodman-Bacon, A. 2018. Public insurance and mortality: Evidence from Medicaid implementation. Journal of Political Economy 126(1):216–262.

Hagan, J. F., J. Shaw, and P. Duncan, Eds. 2017. Bright futures: Guidelines for the health supervision of infants, children, and adolescents, 4th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics.

Halfon, N., and C. B. Forrest. 2018. The emerging theoretical framework of life course health development. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. Pp. 19–43.

Hemmeter, J., and M. Bailey. 2015. Childhood continuing disability reviews and age-18 redeterminations for Supplemental Security Income recipients: Outcomes and subsequent program participation. SSA Research and Statistics Note No. 2015-03.

HHS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). 2023. Social determinants of health. https://health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health (accessed June 14, 2023).

Hong, X., T. Bartell, and X. Wang. 2021. Gaining a deeper understanding of social determinants of preterm birth by integrating multi-omics data. Pediatric Research 89(2):336–343.

Hoyert, D. L. 2023. Maternal mortlity rates in the United States, 2021. National Center for Health Statistics. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/maternal-mortality/2021/maternal-mortality-rates-2021.htm (accessed January 25, 2024).

Hoynes, H., M. Page, and A. H. Stevens. 2011. Can targeted transfers improve birth outcomes? Evidence from the introduction of the WIC program. Journal of Public Economics 95(7–8):813–827.

Hoynes, H., D. Miller, and D. Simon. 2015. Income, the Earned Income Tax Credit, and infant health. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 7(1):172–211.

Hoynes, H., D. W. Schanzenbach, and D. Almond. 2016. Long-run impacts of childhood access to the safety net. American Economic Review 106(4):903–934.

Iezzoni, L. I. 2011. Eliminating health and health care disparities among the growing population of people with disabilities. Health Affairs 30(10):1947–1954.

Jackman, M., L. Sakzewski, C. Morgan, R. N. Boyd, S. E. Brennan, K. Langdon, R. A. M. Toovey, S. Greaves, M. Thorley, and I. Novak. 2022. Interventions to improve physical function for children and young people with cerebral palsy: International clinical practice guideline. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology 64(5):536–549.

Jensen, E. A., E. E. Foglia, K. C. Dysart, R. A. Simmons, Z. H. Aghai, A. Cook, J. S. Greenspan, and S. B. Demauro. 2019. Adverse effects of small for gestational age differ by gestational week among very preterm infants. Archives of Disease in Childhood Fetal and Neonatal Edition 104(2):F192–F198.

Johnson, A., P. D. Dobbs, L. Coleman, and S. Maness. 2023. Pregnancy-specific stress and racial discrimination among U.S. women. Maternal and Child Health Journal 27(2): 328–334.

Kennedy-Moulton, K., S. Miller, P. Persson, M. Rossin-Slater, L. Wherry, and G. Aldana. 2022. Maternal and infant health inequality: New evidence from linked administrative data. Working paper 30693. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Kose, E., S. M. O’Keefe, and M. Rosales-Rueda. 2022. Does the delivery of primary health care improve birth outcomes? Evidence from the rollout of community health centers. Working paper 30047. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Krahn, G. L., D. K. Walker, and R. Correa-De-Araujo. 2015. Persons with disabilities as an unrecognized health disparity population. American Journal of Public Health 105(S2):S198–S206.

Krieger, N. 2014. Discrimination and health inequities. International Journal of Health Services 44(4):643–710.

Kumaran, K., C. Osmond, and C. H. D. Fall. 2017. Early origins of cardiometabolic disease. In Disease control priorities, 3rd ed. Vol. 5: Cardiovascular, respiratory, and related disorders, edited by D. Prabhakaran, S. Anand, T. Gaziano, J. Mbanya, Y. Wu, and R. Nugent. Washington, DC: World Bank. Pp. 37–55.

Lorch, S. A., and E. Enlow. 2016. The role of social determinants in explaining racial/ethnic disparities in perinatal outcomes. Pediatric Research 79(1-2):141–147.

Lurbe, E., and J. Ingelfinger. 2021. Developmental and early life origins of cardiometabolic risk factors. Hypertension 77(2):308–318.

Mahmoodi, Z., M. Karimlou, H. Sajjadi, M. Dejman, M. Vameghi, and M. Dolatian. 2013. Working conditions, socioeconomic factors and low birth weight: Path analysis. Iran Red Crescent Medical Journal 15(9):836–842.

Montoya-Williams, D., M. Passarella, and S. A. Lorch. 2020. The impact of paid family leave in the United States on birth outcomes and mortality in the first year of life. Health Services Research 55(Suppl 2):807–814.

Morgan, C., L. Fetters, L. Adde, N. Badawi, A. Bancale, R. N. Boyd, O. Chorna, G. Cioni, D. L. Damiano, J. Darrah, L. S. de Vries, S. Dusing, C. Einspieler, A. C. Eliasson, D. Ferriero, D. Fehlings, H. Forssberg, A. M. Gordon, S. Greaves, A. Guzzetta, M. Hadders-Algra, R. Harbourne, P. Karlsson, L. Krumlinde-Sundholm, B. Latal, A. Loughran-Fowlds, C. Mak, N. Maitre, S. McIntyre, C. Mei, A. Morgan, A. Kakooza-Mwesige, D. M. Romeo, K. Sanchez, A. Spittle, R. Shepherd, M. Thornton, J. Valentine, R. Ward, K. Whittingham, A. Zamany, and I. Novak. 2021. Early intervention for children aged 0 to 2 years with or at high risk of cerebral palsy: International clinical practice guideline based on systematic reviews. JAMA Pediatrics 175(8):846–858.

Murray, M. J., and J. Richardson. 2017. Neonatology. In Core concepts of pediatrics, 2nd ed. Galveston, TX: University of Texas Medical Branch.

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2015. Mental disorders and disabilities among low-income children. Edited by T. F. Boat and J. T. Wu. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NASEM. 2016. Speech and language disorders in children: Implications for the Social Security Administration’s Supplemental Security Income program. Edited by S. Rosenbaum and P. Simon. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NASEM. 2018. Opportunities for improving programs and services for children with disabilities. Edited by A. J. Houtrow, F. R. Valliere and E. Byers. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NASEM. 2021. Childhood cancer and functional impacts across the care continuum. Edited by P. A. Volberding, C. M. Spicer, T. Cartaxo, and L. Aiuppa. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Penman-Aguilar, A., M. Talih, D. Huang, R. Moonesinghe, K. Bouye, and G. Beckles. 2016. Measurement of health disparities, health inequities, and social determinants of health to support the advancement of health equity. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 22(Supplement 1):S33–S42.

Pignotti, M. S., and G. Donzelli. 2008. Perinatal care at the threshold of viability: An international comparison of practical guidelines for the treatment of extremely preterm births. Pediatrics 121(1):e193–e198.

Profit, J., J. B. Gould, M. Bennett, B. A. Goldstein, D. Draper, C. S. Phibbs, and H. C. Lee. 2017. Racial/ethnic disparity in NICU quality of care delivery. Pediatrics 140(3):e20170918.

Reber, L., J. M. Kreschmer, T. G. James, J. D. Junior, G. L. DeShong, S. Parker, and M. A. Meade. 2022. Ableism and contours of the attitudinal environment as identified by adults with long-term physical disabilities: A qualitative study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19(12):7469.

Roberts, D. E. 2023. The problem with race-based medicine. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation 102(7):567–570.

Rupp, K. 2005. Profile of children with disabilities receiving SSI: Highlights from the National Survey of SSI Children and Families. Social Security Bulletin 66:21.

Saenger, P., P. Czernichow, I. Hughes, and E. O. Reiter. 2007. Small for gestational age: Short stature and beyond. Endocrine Reviews 28(2):219–251.

Saigal, S., and L. W. Doyle. 2008. An overview of mortality and sequelae of preterm birth from infancy to adulthood. Lancet 371(9608):261–269.

Sigurdson, K., B. Mitchell, J. Liu, C. Morton, J. B. Gould, H. C. Lee, N. Capdarest-Arest, and J. Profit. 2019. Racial/ethnic disparities in neonatal intensive care: A systematic review. Pediatrics 144(2):e20183114.

Smith, M., O. Calder-Dawe, P. Carroll, N. Kayes, R. Kearns, E. J. Lin, and K. Witten. 2021. Mobility barriers and enablers and their implications for the wellbeing of disabled children and young people in Aotearoa New Zealand: A cross-sectional qualitative study. Wellbeing, Space and Society 2:e100028.

Solar, O., and A. Irwin. 2010. A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health. Geneva: World Health Organization.

SSA (Social Security Administration). 1991. Supplemental security income: Determining disability for a child under age 18 (final rules with request for comments; 56 FR 5534). Hearings, appeals, and litigation law manual. Woodlawn, MA: Social Security Administration. Part II-4-1-1.

SSA. 2014. SSI annual statistical report, 2013: Children under age 18. https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/statcomps/ssi_asr/2013/sect04.html (accessed July 20, 2023).

SSA. 2015. Revised listings for growth disorders and weight loss in children. Federal Register 80(70):19522–19530.

SSA. 2023a. Disability evaluation under Social Security: 100.00 low birth weight and failure to thrive: Childhood. https://www.ssa.gov/disability/professionals/bluebook/100.00-GrowthImpairment-Childhood.htm (accessed July 20, 2023).

SSA. 2023b. Monthly statistical snapshot, June 2023. https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/quick-facts/stat_snapshot/2023-06.html (accessed July 20, 2023).

SSA. 2023c. SSI federal payment amounts for 2023. https://www.ssa.gov/oact/cola/SSI.html (accessed July 20, 2023).

Stearns, J. 2015. The effects of paid maternity leave: Evidence from temporary disability insurance. Journal of Health Economics 43:85–102.

Valdez, R. S., and B. K. Swenor. 2023. Structural ableism: Essential steps for abolishing disability injustice. The New England Journal of Medicine 388(20):1827–1829.

WHO (World Health Organization). 2007. International classification of functioning, disability, and health: Children & youth version. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

WHO. 2015. International statistical classification of diseaes and related health problems, 10th revision. 5th ed. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

WHO. 2023. Preterm birth. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/preterm-birth (accessed July 1, 2023).