Low Birth Weight Babies and Disability (2024)

Chapter: 5 Availability and Delivery of Treatments, Services, and Resources

5

Availability and Delivery of Treatments, Services, and Resources

Chapter 2 describes hospital-based interventions and screenings that have improved outcomes among children born preterm and/or low birth weight (LBW). Medical findings in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) may lead to additional service tracks, including treatments that start in the NICU and specific follow-up pathways. Additionally, specialized interventions in the medical setting may be provided for specific identified medical complications, such as cerebral palsy (Noritz et al., 2022a,b). The present chapter provides an overview of treatments, services, and resources available following discharge from the hospital, including their availability and delivery. It also addresses eligibility for Supplemental Security Income (SSI) disability payments on the basis of LBW and, to the extent possible, provides information on differences in outcomes between children who receive such benefits and those who do not.

LANDSCAPE SURROUNDING THE DELIVERY OF TREATMENTS AND SERVICES

The goal of treatments and services for LBW infants is to maximize growth, health, development, and quality of life through the lifespan; this report does not distinguish between the two. Treatments and services include medical care, therapeutic interventions, developmental and educational therapies, and supports and resources provided across multiple systems of care. Guidelines such as the Vermont Oxford Network’s Potentially Better Practices for Follow Through (VON, 2020) emphasize a culture of equity, promotion of development, mitigation of social risk, and quality

improvement to optimize the health and developmental outcomes of LBW infants.

Over the past 50 years, treatments and services for LBW infants defined by both legal statutes and medical guidelines have evolved considerably, influenced by civil rights legislation, changes in community expectations, and the life-course approach. For example, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) mandates free appropriate public education and ensures special education and related services for children and youth aged 3–21 throughout the United States and encourages the provision of early intervention services for children aged 0–2 in the natural environment.1 Additionally, the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) protects eligible individuals against discrimination in critical areas that include access to education, health care, and social services.2 It is increasingly recognized that, to the extent possible, children are best served by living in a community setting, supported by community services and provided a free appropriate public education in the least restrictive environment (Lichstein et al., 2018; Noritz et al., 2022a; Watkinson et al., 2023). The implementation of IDEA and the ADA has had a significant impact on the form of and expectations for services and increased the demand for resources.

As noted above, some of the services received by LBW infants are mandated by law or provided by entitlement, while others are recommended by consensus guidelines of medical or special societies; still others have evidence-based support but are neither mandated nor regulated. Services for LBW children are, in turn, impacted by a complex web of delivery systems that are often administered through the states, which results in variation in eligibility criteria as well as in actual receipt of and the quality of services. This variation stems from differences in, among other factors, state and local regulations; policy and funding decisions; workforces; and systemic factors, including social determinants of health.

As noted, the services and treatments currently available for LBW infants who are discharged to home reflect the influence of the life-course model of care (see Chapter 1), which emphasizes that points in a child’s development at which interventions are provided have long-term impacts. In general, the earlier and more sustained a service is, the higher is its long-term impact on growth and development for LBW infants. Although effectiveness research has not always focused on when it is best to start therapy, it is expected that interventions provided when skills emerge earlier in life are likely to lead to better outcomes compared with those aimed at modifying already learned behavior later on (Damiano and Longo, 2021).

___________________

1 Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, 20 U.S.C. § 1400 (2004).

2 Americans with Disabilities Act, 42 U.S.C § 12101 (1990).

The past 30 years has seen several important changes in the landscape of treatment and service availability and delivery for LBW children. First, increased survival rates at lower gestational ages have resulted in a greater number of children being born LBW (see Chapter 2). Second, the medical field has recognized the importance of attending to attachment and environmental influences as part of care in the NICU and beyond (Kim and Kim, 2022). Third, universal screening for specific conditions, such as hearing loss, in infants born LBW has led to earlier treatment and interventions (Wroblewska-Seniuk et al., 2017). Finally, the ways in which social determinants of health and the impact of structural racism create barriers to treatment and service access are increasingly recognized and understood (Hagan et al., 2017; Halfon and Forrest, 2018).

Parent-reported childhood disability (defined as activity limitations because of chronic conditions) has been on the rise since 1960, with an increase of more than 15 percent occurring between 2001 and 2011 among noninstitutionalized children under age 18 (Houtrow et al., 2014). Houtrow and colleagues (2014) found increases during that timeframe across all age groups, in both males and females, and among Hispanics and non-Hispanic White and Black individuals. Notably, there was a 20.9 percent increase in reported disability related to neurodevelopmental or mental health conditions, while reported disability related to physical health conditions decreased. For example, 1 in 36 children now carry a diagnosis of autism, compared with 1 in 150 just 20 years ago (CDC, 2023b; Maenner et al., 2023).

Although Houtrow and colleagues (2014) found increases in reported disability across all ages among Hispanics and non-Hispanic White and non-Hispanic Black individuals, the largest increase was among children under age 6. Interestingly, with respect to socioeconomic status, while there were significant increases in reported disability among children living in households at both ends of the income spectrum, the greatest increase was among children in households with incomes 400 percent or more above the federal poverty level. The greater relative increase in the prevalence of disability among more advantaged children may be due to several factors, including better access to care (e.g., diagnostic and treatment services), social differences in seeking and accepting diagnoses of mental health conditions, and undetected diagnostic biases (Houtrow et al., 2014). These changes in the landscape of childhood disability, as well as in recognition of and diagnostic criteria for developmental disabilities, increase demands on the systems that care for these children, resulting in, for example, longer wait times, inability to access services, and burnout among providers, potentially requiring service systems to modify their criteria for what services to provide and for whom.

The following sections describe the treatments and services for which LBW infants who are discharged to the home setting may be eligible.

The description uses a chronological framework beginning at the point of discharge from the hospital setting and transition to home or another setting and proceeding to school-based interventions. The chapter then addresses challenges to accessing medical and disability treatments and services, the particular challenge of navigating fragmented systems of care, and resources and outcomes for low-income children with disabilities.

TRANSITION TO HOME

Guidelines for discharging LBW children from NICU to home emphasize physiologic safety, parental/caregiver preparation for care at home, and follow-up by health care providers with experience in the care of these children (AAP, 2008a). For children with greater levels of medical or social complexity, additional considerations include the availability of home care services, community supports, subspecialty follow-up, and neurodevelopmental follow-up.

While most LBW children are discharged directly to home, some may be transferred to a “transitional care” facility as an intermediate step (Howard et al., 2017). These facilities are designed for children with complex medical needs who no longer require intensive care services but cannot yet be cared for safely at home. Reasons for admission to a transitional care facility may include the need for subacute medical care or additional caregiver training and a waiting period for home care services. In addition to subacute medical care, these facilities may provide nursing services and developmental services and screening, including independent services and those offered under Early Intervention or special education. Transitional care facilities for LBW children are emerging but are not yet commonplace.

Home Care and the Natural Environment

Treatment and services in the home setting are designed to support the health and well-being of the infant in a “natural environment.” The term “natural environment” generally refers to the home or community setting and is defined by Part C of IDEA as “settings that are natural or typical for a same-aged infant or toddler without a disability.”

In-home services vary considerably. They range from agency services to those provided by therapists, home health aides, and private duty nurses. The services provided range from weight checks, to parenting support and medical treatments, to specific developmental therapies (e.g., physical, occupational, and speech-language). In addition, IDEA provides for developmental therapies for eligible LBW infants (discussed later in this chapter) that are provided under the education system for children under 3 years of age. Children covered by Medicaid are also entitled to home health care

services through the Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment provision of the Medicaid statute of 1967 (Foster et al., 2019).

Given the medical complexity of some LBW children, home care services may be substantial, with home care providers becoming integral parts of the lives of families. Home care services can support child health and survival in the home environment, as well as family stability and wellbeing (Boss et al., 2020). The numbers of home care providers able to serve children with complex care needs are, however, insufficient, with barriers including a lack of workforce training, underpayment, and fragmented care delivery systems (discussed later in the chapter) (Foster et al., 2019).

Primary Care Services

Treatment and services for LBW infants immediately following NICU discharge typically originate with and are supported by the medical system, starting with primary care services. All children born LBW will have a primary care physician (PCP) who, in well-child visits, provides routine care, including growth measurements; developmental surveillance and screening at regular intervals; and support for growth, nutrition, and promotion of development. The schedule for these well-child visits is determined by the Periodicity Schedule (AAP, 2022b), which includes up to nine routine visits in the first 2 years of life. Primary care is considered to be universally available, although on average fewer than half of children have a “medical home” (KFF, 2021), that is, a comprehensive system of primary care directed by primary care and involving partnerships with specialty care providers, education providers, and families (AAP, 2023).

The standard for preventive care services, as recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics’ (AAP’s) Bright Futures, includes regular screening and surveillance for developmental, behavioral, and psychosocial needs during well-child visits (AAP, 2008b). The primary care practice reviews the results of this screening and may provide interventions that may include counseling, referral, or resources. The Periodicity Schedule, however, does not provide LBW-specific guidance.

As discussed in Chapter 3, developmental surveillance refers to

a longitudinal process that involves eliciting concerns, taking a developmental history based on milestone attainment, observing milestones and other behaviors, examining the child, and applying clinical judgment during health supervision visits (HSVs) (Lipkin and Macias, 2020). (Zubler et al., 2022, p. 1)

Universal developmental screening is used in the primary care setting to determine quickly and routinely whether a formal intervention or specialist

assessment is needed. Both are helpful in helping to identify whether a child has delays in developmental milestones (AAP, 2022a; CDC, 2023a), after which a referral to Early Intervention can be initiated if the need is identified. Universal screening and surveillance are not specific to LBW infants, but for all these infants receiving primary care, screening and surveillance protocols remain essential to earlier recognition and mitigation of any developmental delays.

Several limitations of the developmental screening process should be noted. First, the screenings are designed for the general population and not for children at increased risk for developmental delay. Second, there are no established LBW-specific norms for the screening tests currently used, which results in uncertainty about the appropriate criteria for identifying risk or delay. Third, LBW children may require more targeted screening methods given their increased risk profile to ensure that newly appearing delays or atypicalities are detected as early as possible. In addition, not all children receive regular primary care and the associated developmental screening and surveillance because of social determinants of health, including lack of adequate health insurance; limited family income and resources; and systemic drivers, such as structural racism and ableism (Houtrow et al., 2022).

Subspecialty Medical Care

The specialized medical and developmental needs of LBW infants often require the direct care of a pediatric subspecialist to provide the necessary medical management and direct follow-up care. NICU discharge protocols often lead to direct referrals and care by subspecialists for specific medical conditions that arise in the NICU. These conditions may include bronchopulmonary dysplasia, often managed by a pediatric pulmonologist in the outpatient setting; periventricular leukomalacia, which may lead to the need for pediatric neurology follow-up; or acute kidney injury, warranting pediatric nephrology follow-up. Pediatric rehabilitation physicians may also be involved in continued therapeutic care and may recommend or advocate for equipment such as orthotic or assistive devices or management of spasticity, sleep, and/or pain. Developmental and behavioral conditions such as autism, complex attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), or depression that become more apparent in later years may lead to referrals to neurodevelopmental neurology, developmental-behavioral pediatrics, or pediatric psychiatry or psychology. Postdischarge guidance for neurodevelopmental follow-up for LBW infants has been provided by the AAP (Davis et al., 2023). Given that pediatric subspecialists are often located at tertiary care academic pediatric centers and that shortages of pediatric subspecialists exist in many fields, access to specialty care remains a significant barrier to treatment and services for LBW children (Patel and Raphael, 2023). It is

also worth noting that pediatric subspecialists are often restricted by the monetary and time costs of developmental screenings, which may exacerbate these barriers (Dobrez et al., 2001). However, recent initiatives have been shown to improve developmental screenings for at-risk children and may work to mitigate barriers and other confounding factors that impede access to quality care (Meurer et al, 2022).

The myriad service needs of LBW children have led to the development of comprehensive neonatal follow-up programs. Postdischarge, high risk infant follow-up (HRIF) programs provide comprehensive medical and developmental surveillance for infants born LBW. The services of subspecialists and therapists providing dedicated management for specific complications, such as technology dependence, chronic lung disease, seizure management, and motor delays, may be coordinated through an HRIF and in some cases may be available as part of a single, integrated visit. HRIF programs vary widely in eligibility criteria, resources, and service provision, including visit frequency; developmental testing; and scope of care, which may range from surveillance to comprehensive care management, including centralized visits and dedicated care coordinators. Criteria for neonatal follow-up programs vary (Litt and Campbell, 2023), including differences by gestational age, birth weight, or illness severity (Litt and Campbell, 2023). Such programs are not consistently available to all LBW infants, raising issues of access and equity. Fraiman and colleagues (2022) found that about half of eligible infants participated in HRIF programs, with significantly less uptake among infants born to Black mothers and those whose primary language was not English, as well as those living in neighborhoods with a “very low” child opportunity index3 relative to those born to mothers who were White, whose primary language was English, and who were living in neighborhoods with a “very high” child opportunity index. In terms of infant characteristics, uptake was lower among those who were born at older gestational ages (~30 weeks versus ~28 weeks), had NICU comorbidities (i.e., bronchopulmonary dysplasia or intraventricular hemorrhage), and were transferred to another facility versus home (Fraiman et al., 2022).

In a study of 237 neonates born at 26–32 weeks gestation and referred to a neonatal follow-up clinic, 62 percent were lost to follow-up over a 2-year period (Swearingen et al., 2020). Swearingen and colleagues (2020) reported results similar to those of Fraiman and colleagues (2022), with loss to neonatal follow-up at first visit or over time being associated with older gestational age at birth (31–32 weeks) and being born to a Black mother, and a diagnosis of bronchopulmonary dysplasia, but not intraventricular

___________________

3 The Child Opportunity Index offers “a population-level surveillance system of child neighborhood opportunity, [defined] as neighborhood-based conditions and resources conducive to healthy child development” (Acevedo-Garcia et al., 2014, p. 1948).

hemorrhage, being associated with increasing follow-up over time. Hintz and colleagues (2019) also found an association between birth to Black mothers and lower odds of attending a first HRIF visit, and between a history of severe intracranial hemorrhage and higher odds of attendance. Other factors associated with HRIF attendance or increasing attendance include prenatal steroid administration, older maternal age (30–39 versus 20–29 years), lower birth weight (≤750 versus 1251–1499 grams; ~1122–1340 grams), private insurance, two parents as primary caregivers, higher HRIF program volume, and longer hospital stay length. Other factors associated with nonattendance or attrition include maternal cigarette smoking and, in one study, greater distance to HRIF program (Hintz et al., 2019; Swearingen et al., 2020). Swearingen and colleagues (2020) found that parent and provider scheduling issues accounted for 94.6 percent of loss to follow-up (76.2 and 18.4 percent, respectively), while parent perception of appropriate development accounted for 3.4 percent, lack of insurance coverage for 1.4 percent, and parent perception of alternative resources for 0.6 percent.

Early Intervention

Early Intervention (EI) refers to “the services and supports that are available to babies and young children with developmental delays and disabilities and their families”: Services may include speech therapy, physical therapy, and other services depending on the needs of the child and family (CDC, 2023c).4 Referral to EI can come from multiple sources, including parents and medical clinicians; for example, many LBW children are directly referred from the NICU or HRIF program. In 33 states, some subset of infants born LBW are automatically eligible for EI services under IDEA Part C; in the remainder of states, additional review for eligibility is required.

The EI team, which includes the parents, conducts a multidisciplinary assessment to identify the needs and priorities of the child and family to help identify the need and eligibility for specific services, such as occupational, physical, and speech-language therapy.5 After reviewing the assessment results, the EI team develops an Individualized Family Service Plan (IFSP), a goal-directed therapeutic plan. Implementation of the IFSP is overseen by a case manager. The IFSP is reviewed every 6 months to determine whether goals need to be modified. Depending on the needs, therapy services may be provided, most commonly in the home, to support the achievement of goals. Services may also include additional components such as applied behavioral analysis and augmentative and alternative communication.

___________________

4 34 CFR § 303.13 - Early Intervention services.

5 34 CFR § 303.321 - Evaluation of the child and assessment of the child and family.

At age 3 years, the need for services is reevaluated, and if the child is deemed eligible, services may continue to be provided by the child’s school system under IDEA Part B, described below. While IDEA mandates free appropriate public education (i.e., special education and related services),6 access to services can vary by local and state availability and regulations. Note that beginning at age 3 years, many LBW children who qualify will receive services through their state Medicaid long-term care program. Some may continue to receive EI services through their state’s IDEA Part C Extension Program. These children include those who qualify for IDEA Part B preschool services, as well as those with major medical conditions whose exposure to other children must be limited and those in low-resourced communities where comprehensive preschool services are limited.

EI is the backbone of therapeutic developmental services following discharge from the NICU. Early Head Start (birth to age 3) and Head Start (ages 3–5) are federally funded programs for children from income-eligible families that promote development and learning to help prepare children to succeed in school (ChildCare.gov, n.d.). These programs also provide support for children with identified physical and developmental delays, encourage family involvement in their child’s learning, and may link children and families to other available services.

A Cochrane Review and meta-analysis of 25 studies of EI for LBW infants showed statistically significant improvement in cognitive scores in infancy that persisted to preschool (Spittle et al., 2015). The authors identify primary and secondary objectives for this review. The primary objective was to compare the effectiveness of EI programs provided post–hospital discharge in promoting cognitive and motor outcomes among preterm infants compared with outcomes for preterm infants who received standard medical care during infancy, preschool age, school age, and adulthood. Secondary objectives included identifying effects of gestational age, birth weight, and brain injury on cognitive and motor outcomes; effects of timing on EI during inpatient stay with a postdischarge treatment component compared with standard medical follow-up; and effects of interventions focused on the parent–infant relationship, infant development, or both compared with standard medical follow-up. This review is important as it coalesces data for infants born extremely LBW (<1000 grams), very LBW (1000–1500 grams), and LBW (1500–2500) grams—all considered high-risk categories in the studies examined. The most important time window was found to be in infancy (<12 months of age) for early assessment and intervention.

Key findings from this review for at-risk infants reinforce that EI improves cognitive outcomes during infancy (developmental quotient [DQ]

___________________

6 34 CFR § 303.15 - Free appropriate public education.

standardized mean difference [SMD] 0.32) and preschool age (intelligence quotient [IQ] SMD 0.43) while also having a small effect on motor outcomes during infancy (motor scale DQ SMD 0.10). EI also has been shown to improve the family’s coping mechanisms and to strengthen the infant–parent bond (Palmer et al., 2023). Parent participation is the best predictor of outcomes for children at risk for disability in the first year of life (Landa, 2018; McManus et al., 2019).

EARLY LEARNING AND THE SCHOOL ENVIRONMENT

As described previously, IDEA is the federal law implemented in each state that mandates a free and appropriate public education for all eligible children with disabilities throughout the United States.7 Children become eligible for IDEA Part B services at 3 years of age if they have one or more of 13 qualifying disabilities and are found to require special instruction designed to help them access the general education curriculum. The child’s local public school district must either provide the services or pay for them out of district if they cannot provide them. However, it is worth noting that different states also have discretion in defining criteria for eligibility for Part B services.

Children are screened and evaluated through the local Child Find program. Some, like many LBW children, are directly referred from EI programs. Child Find programs are integrated into each school district in each state and tasked with locating and evaluating all children with disabilities aged 0 through 21 years who require special education and related services as part of IDEA. Anyone can refer a child to Child Find. Domains evaluated in preschoolers by Child Find include motor, communication, cognitive, social-emotional, and adaptive. If the child is found to need special education and related services, the educational team (including caregivers) prepares an Individualized Education Plan (IEP). Goals and services are chosen to optimize the child’s abilities and implemented, but do not have to be limited to a preschool setting in the child’s local public school. In fact, recent federal initiatives encourage more children to be served outside of public school facilities, such as childcare centers or community-based preschool settings, as long as these outside settings are identified as the least restrictive learning environment (Berman et al., 2022; HHS and DOE, 2015).

The child’s progress on the IEP is reviewed each year at a team meeting that includes the child’s caregivers. A full evaluation across domains is completed every 3 years by the Multidisciplinary Education Team. The IEP can remain in place through preschool, elementary school, middle school, and high school as long as the child requires special education

___________________

7 Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, 20 U.S.C. § 1400 (2004).

and related services in order to access the general education curriculum successfully. Specialists available to support the child may include special education teachers, learning disability specialists, psychologists, speech-language pathologists, educational audiologists, occupational and physical therapists, and counselors. Children who may require specialized supports can be referred and evaluated at any time during their educational career. Supports are provided during the day either in the classroom or in group or individual sessions outside of the classroom.

High school students on IEPs are required to have a transition plan in place by age 16 (although some states begin this process earlier). The transition plan may include vocational preparation and development of skills for activities of daily living to aid in the transition from school services to community activities, postsecondary education, employment, and independent living. High school students with IEPs and significant disabilities can receive support and instruction through the school district through 21 years of age.

CHALLENGES TO ACCESSING TREATMENTS AND SERVICES

A number of barriers affect access to and receipt of treatments and services available to children born LBW. These include financial constraints, geographic and physical inaccessibility, inadequate EI, limited health care resources, variation in eligibility criteria across service sectors and localities, and difficulty navigating transitions between services (such as IDEA eligibility) (Berman et al., 2022; DeVoe et al., 2009; HRSA, 2022; Musumeci and Chidambaram, 2019; Rural Health Information Hub, 2022; Ziegler, n.d.). In addition, the complexity of managing the child’s diverse services can be daunting for families.

It is challenging to assess the impact of nonreceipt of services because of ethical concerns about withholding services for research purposes; therefore, most of the available evidence comes from studies examining differences in outcomes across groups or regions that vary on one or more of these factors. Furthermore, most of the evidence is specific not to children born LBW but to the larger population of children with disabilities. Two studies provide insight into the negative impact of absent or delayed treatment and services. These studies, which looked at the effect of disruption of treatments and services among children with cerebral palsy during the COVID-19 pandemic, found a decline in function, worsened deformities, and increased pain and spasticity, among other effects (Bhaskar et al., 2022; Dogruoz Karatekin et al., 2021).

The complexity and fragmentation of treatments and services for LBW infants can be examined by applying the framework of long-standing principles of a system of services for children and youth with special health care needs. These principles of care emphasize the need for a medical

home, well-coordinated care, family–professional partnership, and adequate insurance. In 2022, the Maternal and Child Health Bureau (MCHB) published the Blueprint for Change for children and youth with special health care needs (CYSHCN), emphasizing that improvements in health equity, family well-being, access to services, and health care financing are needed to improve the system of services for this population (Brown et al., 2022; MCHB, 2023; McLellan et al., 2022). The Blueprint for Change data review found that more than 85 percent of CYSHCN families reported not receiving services in a well-functioning system (McLellan et al., 2022). Because of the presence of a chronic medical condition requiring ongoing care, many LBW infants fall under the definition of CYSHCN.

The Blueprint also recognizes the roles of structural racism and ableism in barriers to service access and public policies for CYSHCN. Additional disparities in family engagement, care coordination, and service receipt by race, ethnicity, household income, and disability status have been reported. Families describe stress and foregone care due to difficulties in accessing services and the need to personally provide direct home care and care coordination (McLellan et al., 2022).

The importance of early identification of needs and sustained treatments and services has been well established. Federal and state initiatives to develop a system of services for CYSHCN date back several decades, with increasing codification in law such as the Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment (EPSDT) benefit, IDEA, and the ADA. The EPSDT benefit “provides comprehensive and preventive health care services for children under age 21 who are enrolled in Medicaid,” including dental, mental health, developmental, and specialty services (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2023). The last 20 years has seen efforts to implement universal screening, surveillance, and comprehensive service delivery to address the needs of all children, including the specific service needs of LBW infants. These efforts have led to some successes but not to widespread access to treatments and services. For example, challenges for families seeking to transition from IDEA Part C to IDEA Part B services persist as the result of a range of demographic factors, such as geographic location, cultural and linguistic barriers, immigrant status, and/or socioeconomic circumstances (Berman et al., 2022; Ward et al., 2006). In addition, while IDEA mandates a free and appropriate public education for eligible children, it also requires school districts to spend a proportionate amount of IDEA funds to provide equitable services to eligible children who are “parentally placed” in nonpublic/private schools (DOE, 2011). These children are not, however, entitled to the same services they would receive if they were enrolled in a public school or were placed in a nonpublic school by the determination of the school district (DOE, 2011). As a result, many families continue to describe the system as fragmented.

Guidelines and expectations for LBW treatments and services at home and in community settings are impacted by workforce and system factors. Evidence suggests that while almost all children have a PCP, there are substantial gaps in attendance at recommended primary care visits, subspecialty visits, comprehensive HRIF visits (Hintz et al., 2019; Swearingen et al., 2020), and delivery of EI and special education services for eligible infants. Factors contributing to these gaps include workforce shortages and maldistribution; fragmentation of care services; and navigation demands placed on caregivers (see below), which lead to significant stress and frustration. Even the availability of services does not automatically result in access; the majority of parents reported their infants aged 9–35 months had not received developmental screening using a parent-completed screening tool in the prior 12 months (HHS, 2023).

In a study of infants born preterm (25–32 weeks gestation), D’Agostino and colleagues (2015) found that only 43 percent had been fully adherent to the eight well-child visits recommended in the AAP health supervision visit schedule from 1 to 18 months of age. Researchers also found that the children born preterm had had a higher number of non–health supervision visits, although these nonpreventive visits did not compensate for the preventive visits missed, resulting in immunization delays, as well as gaps in developmental assessments and screening for lead exposure and anemia (D’Agostino et al., 2015). As in the general pediatric population, two of the risk factors associated with nonadherence to the AAP health supervision schedule among preterm infants in the study were lack of private insurance and being Black; chronic illness was also associated with nonadherence in the preterm group (D’Agostino et al., 2015). Continuity of provider care was found to be a strong predictor of adherence to preventive care for the preterm group, as in the general pediatric population (D’Agostino et al., 2015). Similar to the finding of Swearingen and colleagues (2020) that scheduling issues accounted for most of the loss to follow-up in HRIF clinics, D’Agostino and colleagues (2015) found that close to half of the missed preventive care visits had never been scheduled during the time windows in which they were due.

The workforce that provides treatments and services for LBW infants includes medical professionals, mental health professionals, therapists, educators, and many others that support families at home and in community settings. Direct service providers thus are based in different sectors (e.g., medical, educational, financial), with different legal and financial support systems.

Access to the specialized workforce often needed for LBW infants also is limited by supply and geographic distribution. As a result of the shortage of pediatric subspecialists and their clustering around specialty centers, LBW infants may live hundreds of miles away from the specialized

providers they need. Further challenges to meeting the specialized needs of LBW infants include shortages of educators, therapists, home care services, and educational facilities, which in turn may lead to delays in diagnosis and treatment and ultimately the failure to receive services for which these infants are eligible. Training needs, payment models, and variation in eligibility criteria for services add to the inaccessibility of services. A recent audit of New York State’s EI program, for example, found that more than half of eligible infants had failed to receive the services to which they were entitled (DiNapoli, 2023).

NAVIGATING FRAGMENTED SYSTEMS OF CARE

Identification of the need for services among children born LBW typically begins within the medical system because of the child’s initial stay in the hospital and the need for medical subspecialty follow-up care and scheduled routine well-child visits in the primary care setting. Identification of service needs generally leads to a series of referrals; further screening and testing; and finally receipt of services, perhaps in a different service sector (e.g., education) and facilitated by additional sectors (e.g., disability services and financing). This process is sometimes described as care integration, as well as newer terms such as human-centered design and system navigation (Kuo et al., 2018b; Turchi et al., 2014). In turn, care integration may lead to still more services, such as care coordination, service coordination, and care navigation, for which an LBW child may be eligible. Families, however, describe the system as fragmented and frustrating and report often having to navigate it with minimal support. This fragmentation places many LBW children at risk of not receiving services for which they may be eligible.

Taking a more detailed look at this challenge, treatments and services for LBW children, even if a child is eligible, may depend on a series of events that include screening in one setting, referral to another provider, and a separate determination of service need. These referrals may occur within a system or across systems, each with varying levels of complexity and challenges. For example, a PCP may refer the child to a subspecialist, who may be able to assume direct management for the referred condition or share management responsibilities with the PCP. However, referrals across systems are also common, such as from the medical system (developmental concern) to the education system (service provision).

Postdischarge, referrals for treatments and services may originate from the NICU or parents/caregivers, or may be facilitated by a referring provider, an intermediary entity (such as a care provider), or another therapy discipline in states with direct access to care. Feedback to the referring provider may or may not occur. At each referral point, another screening or formal evaluation may take place to determine service eligibility,

leading to multiple steps from evaluation, to determination, to service provider assignment before a service is received. These evaluations may be further contingent on specific requirements within communities and states. As an example, the exchange of information involving medical providers is governed by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, while that involving educational providers is governed by the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act. As noted previously, while some states stipulate direct referral to EI for infants meeting all LBW criteria (e.g., less than 1000 grams at birth in Tennessee and Illinois), other states may establish a different process for determining the eligibility of LBW infants for EI services. States also set their own criteria for qualifying for EI, as well as benchmarks for the time from referral to evaluation or receipt of services (Friedman-Krauss and Barnett, 2023). Even with direct referral from the NICU, however, there can be a substantial delay in the process of evaluation and actual receipt of services within the EI system (Baggett et al., 2020).

The role of care coordination in access to services when the services the child and family need are difficult to access or sustain is increasingly recognized (Turchi et al., 2014). Designated care coordinators, who may also be known as service coordinators or service navigators, provide such services as assisting families in scheduling appointments; arranging transportation to increase access to services; and proactively planning for EI, services, and special education. LBW infants may be specifically eligible for care coordination that facilitates entry to and coordination of services, as well as access to services, including transportation and interpreter services. Care coordination can come from a variety of locations, including the medical home, an HRIF program or other specialty clinic, EI, managed care or an accountable care organization, or a dedicated care management agency such as a “health home.” Some children can have multiple coordinators, leading to a potentially ironic situation in which families end up “coordinating the coordinators” or acting as the primary care coordinator themselves (Kuo et al., 2018a).

Care mapping is another tool designed to help caregivers track and coordinate needed services (Antonelli and Lind, n.d.; Boston Children’s Hospital, 2023). Care mapping creates a comprehensive snapshot of services and resources that may be needed by a child and family. Typically, a family creates a care map by diagramming the components of services for their children and further grouping the services by sector. A typical care map for a child born LBW demonstrates the range of medical, home, educational, and facility-based services needed. The services are supported by access to insurance, transportation, income support, and community-based resources. Care mapping can therefore help families work together with care professionals to coordinate and plan care.

RESOURCES AND OUTCOMES FOR LOW-INCOME CHILDREN WITH DISABILITIES

The families of low-income LBW infants face a number of particular challenges. Both during NICU stays and after discharge, parents face a number of out-of-pocket expenses. They also need to spend significant time with their infants (Parker et al., 2023). These time commitments make it difficult for parents to work full time, and many parents in the United States receive no form of paid family leave. In addition, these families are likely to be negatively affected by social determinants of health, such as unstable and inadequate housing, food insecurity, unsafe neighborhoods, and structural racism (e.g., Cook et al., 2004; Matoba et al., 2019a,b; Parker et al., 2023).

At the same time, however, infants born to low-income families may benefit from a number of social safety net programs and targeted policy interventions, including cash transfers through the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program; food support through the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly Food Stamps) and the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children; and publicly provided health insurance through Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program. A growing body of evidence suggests that these programs reduce the likelihood of infants being born LBW, and that they have positive effects on other child outcomes as well (see Aizer et al., 2022) for a recent review). In addition, expansions of public health insurance through Medicaid (Currie and Gruber, 1996; Goodman-Bacon, 2018), the establishment of community health centers (Kose et al., 2022), and paid family leave programs (Montoya-Williams et al., 2020; Stearns, 2015) have all been shown to reduce infant mortality. However, none of this evidence is specific to LBW infants or infants with health conditions associated with LBW.

Low Birth Weight and Supplemental Security Income

As noted in Chapter 1, LBW infants born to low-income families may be eligible for cash transfers through the Social Security Administration’s (SSA’s) SSI program, which in most states comes with health insurance through Medicaid and food benefits through SNAP. SSI has provided cash transfers to low-income children with disabilities since its inception in 1974. The program initially served very few children, but the 1991 Supreme Court decision Sullivan v. Zebley expanded eligibility for children, and participation grew rapidly as a result, roughly tripling from 300,000 children in 1991 to 900,000 in 1996. SSI participation among children continued to grow through the 2000s, peaking at 1.3 million children in 2013 (1.7 percent of all children and 8.3 percent of children in households with income

below the federal poverty level), and falling since then. Neither the increase in participation in the 2000s nor the decrease since 2013 has been completely explained (Aizer et al., 2013; GAO, 2012; Schmidt and Sevak, 2017).

Children born preterm and/or LBW who meet the SSI financial eligibility requirements may qualify for benefits in two ways. First, as described in Chapter 1, LBW is its own medical listing for SSI eligibility. Under listing 100.04A, infants with birth weight under 1200 grams are automatically medically eligible for SSI; under listing 100.04B, infants at higher birth weights may be automatically eligible depending on their gestational age (see Table 1-1 in Chapter 1). As discussed previously, however, the weight criteria in the LBW listing do not correspond to any of the current standard medical definitions of LBW (<2500 grams), very LBW (<1500 grams), or extremely LBW (<1000 grams), and a relatively large number of infants considered LBW by the medical community would not qualify automatically for SSI based on the SSA rules even if they met the financial criteria. Of note, the 1200 gram criterion for SSI falls between the medical criteria for extremely LBW and very LBW. An analysis of raw birth certificate data for 2021 (Table 1-2) in Chapter 1 indicates that about 50 percent of infants born very LBW would not have met the current LBW listing criteria.

For children who are developing at the appropriate weight for gestational age, girls reach 1200 grams between 31 and 32 weeks gestation, while boys do so between 30 and 31 weeks gestation (Fenton and Kim, 2013). Birth during this timeframe is considered very preterm (i.e., 28–31 6/7 weeks gestational age). For children who are large for gestational age, birth weight does not drop below 1200 grams until 27 weeks for girls and 26 weeks for boys (Fenton and Kim, 2013). Birth during this timeframe is considered extremely preterm (i.e., less than 28 weeks). As discussed in Chapter 2, among children born preterm, gestational age is a better predictor than birth weight of survival and morbidity and takes account of variations in birth weight at a given gestational age. A birth weight of 1500 grams is close to the 50th percentile for weight at 32 weeks gestation, after which the risk of severe impairments decreases dramatically.

Similarly, the criteria for birth weight relative to gestational age shown in Table 1-1 in Chapter 1 do not correspond to the percentile cutoffs (10th or 3rd) used by the medical community to identify neonates who are considered small for gestational age (SGA) or severely SGA (Fenton and Kim, 2013). As described in Chapter 2, infants born SGA are at increased risk of having medical morbidities and developmental delays associated with poor growth of the brain and body. With respect to SSI, infants who are SGA (less than the 10th percentile for gestational age) make up an important category of LBW infants born after 32 weeks gestation because their physiology and outcomes are more similar to those of appropriate-weight infants who are born prior to 32 weeks.

Infants born preterm and/or LBW who do not qualify for SSI based on the LBW listing criteria may still qualify based on the presence of other diagnosed health conditions, but such determinations require diagnosis of the specific health conditions and additional documentation. In addition, as described in Chapter 4, the presence of many chronic health conditions associated with preterm birth or LBW will not be diagnosed until later in the developmental process. Cerebral palsy, for example, would not be diagnosed before 5–12 months of age. Other conditions (e.g., autism spectrum disorder, speech sound disorder, cognitive dysfunction) typically are diagnosed much later.

For most children receiving SSI benefits for disability, SSA conducts periodic Continuing Disability Reviews (CDRs), typically once every 3 years, to determine whether the recipient is still considered to have a qualifying disabling condition. Children who initially qualify based on the LBW listing are expected to be reevaluated at 1 year unless, at the time of the initial determination, SSA found that the infant would be expected to remain disabled at age 1. Altered developmental trajectories and/or diagnosed health conditions, such as those described in Chapter 4, can provide an avenue for continued receipt of benefits following the CDR at 1 year. Nevertheless, Hemmeter and Bailey (2015) found that between 1998 and 2008, CDRs led to cessation of eligibility for almost half of LBW SSI participants. Within 10 years of cessation, 9.4 percent of former LBW recipients had returned to the SSI rolls, and half of these had returned within the first 4 years after cessation.

SSA also conducts a redetermination of eligibility based on the adult SSI disability determination process when child SSI recipients turn age 18. The difference between SSA’s determination processes for children and adults introduces challenges for establishing/sustaining disability benefits across the 18-year-old threshold for child SSI recipients (NASEM, 2021). Hemmeter and Bailey (2015) show that more than a third of child SSI recipients lose eligibility at the age 18 redetermination, and SSI youth and their families face significant challenges in the transition to adulthood (Wittenburg and Livermore, 2021).

As described previously, some children with neurodevelopmental impairments and other health conditions associated with LBW or preterm birth require special instruction designed to help them access the general education curriculum. These children have IEPs that specify goals and services designed to optimize their abilities. As noted earlier, students with IEPs must have a transition plan in place by age 16, which may include vocational preparation and development of skills for activities of daily living to aid in the transition from school services to community-based activities, including employment. High school students with significant disabilities who have an IEP can receive support and instruction through the school district through

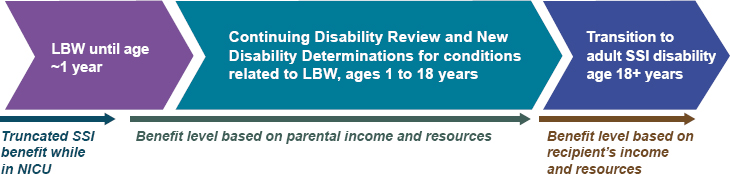

age 21. A person determined by SSA to no longer be medically eligible for benefits following the CDR at age 18 may continue to receive benefits while participating in an approved program of special education (e.g., IEP, 504 plan), vocational rehabilitation, or similar services (SSA, 2022). Also presented as Figure 1-1 in Chapter 1, Figure 5-1 illustrates the relationship between the SSA disability processes for children born LBW and the ages at which those processes occur, highlighting transition points within the timeline. Most notable are the reassessment at 12 months of children who originally qualify for SSI benefits based on LBW listing criteria and the reassessment at age 18 of those who are still receiving benefits to determine whether they continue to qualify under adult criteria.

Outcomes for Children Receiving Supplemental Security Income

Children receiving SSI benefits face high levels of disadvantage. Fully 71 percent live in a single-parent family (Bailey and Hemmeter, 2015), and in 2000 roughly half were non-White (Wittenburg, 2011). Cash transfers through the SSI program make up, on average, 45 percent of income for families of child beneficiaries. Almost half the parents of child SSI recipients have no earned income (Davies et al., 2009; Rupp, 2005), and SSI has been shown to be effective in reducing poverty for families of child beneficiaries (Bailey and Hemmeter, 2015; Duggan and Kearney, 2007). SSI benefits thus provide an important source of family income for children with disabilities.

Cash support through SSI has become increasingly important for families with children since the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWORA) of 1996 replaced the Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) program with the TANF program and gave states a great deal of flexibility to redesign their cash welfare programs. As a result, large reductions occurred in the number of low-income children receiving benefits through TANF. By 2015, 11 states had more children on SSI than on TANF, and expenditures on child SSI currently exceed federal and

state expenditures on TANF (Wittenburg et al., 2015). Evidence suggests that when benefits through AFDC/TANF become less available/more restrictive, SSI participation among single-parent families increases (Schmidt and Sevak, 2004). Although SSI is a federal program, it has varying local reach. Research has documented wide geographic variation in receipt of SSI among children living in poverty that is not fully explained by local economic conditions or differences in health (Schmidt and Sevak, 2017). The resources available to SSI recipients vary substantially across geographic locations as well (Wittenburg and Livermore, 2021), and rates of cessation of SSI at age 18 range from 20 percent to 47 percent across states (Hemmeter et al., 2017).

The evidence on SSI’s effects on outcomes for children comes largely from older children. Deshpande (2016) examined differential removal of children from SSI before and after the age 18 redetermination policy was implemented in 1996 and found that while youth removed from SSI at age 18 experienced increased earnings, those earnings made up only one-third of their loss in SSI cash transfers. Using a similar research design, Deshpande and Mueller-Smith (2022) found that youth removed from SSI at age 18 experienced a 20 percent increase in criminal charges over the next two decades and a 60 percent increase in the probability of being incarcerated.

A number of SSA demonstration projects (authorized in the Social Security Disability Amendments of 1980) directly targeted teenagers and young adults, with the goal of determining what policies would facilitate a successful transition to adulthood for SSI youth. These demonstration projects, summarized by Wittenburg and Livermore (2021), show in general that services and supports are important in improving outcomes for those youth and that more intensive services tend to be more successful. One example comes from the Promoting Readiness of Minors in SSI (PROMISE) demonstration, which included a focus on case management that connected recipients and families directly to services. PROMISE’s implementation of services was led by state agencies and required collaboration across those agencies, which reduced the amount of complexity faced by families. In addition, Wittenburg and Livermore (2021) make clear that any attempts to provide successful interventions for children receiving SSI require an understanding of child development processes (both cognitive and noncognitive) and of parental investments in children, both of which may be affected by the SSI program, as well as by the general challenges faced by low-income families (Schmidt, 2021).

Very little research exists on health or other outcomes for children who receive SSI disability payments on the basis of LBW, and there is no evidence to date on outcomes for eligible nonparticipants. Parker and colleagues (2023) provide suggestive evidence that SSI income may be protective against developmental risk among families with very LBW children facing material hardships.

Guldi and colleagues (2022) use data from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Birth Cohort (ECLS-B) and a regression discontinuity approach to examine the effects of SSI eligibility based on the SSI 1200 gram cutoff. Their results suggest that the SSI 1200 gram cutoff (which, as noted previously, is a cutoff not used by the medical community) matters a great deal in terms of participation: infants just under the threshold are 150 percent more likely to participate in SSI compared with similar infants just above the threshold. These authors also show that SSI eligibility for LBW infants reduces the likelihood of ever being without insurance in the first 9 months of life. SSI eligibility based on LBW does not change the probability of parental employment, but it reduces mothers’ hours worked by approximately 20 hours per week. It also improves parenting behavior, as measured by the Nursing Child Assessment Teaching Scale (NCATS), by 12 percent relative to parenting of infants just above the 1200 gram cutoff. The authors found no effects of LBW eligibility on infant mortality. However, Hemmeter and Davies (2019) examined infant mortality among SSI applicants. They found that, all else being equal, infants awarded SSI based on LBW were less likely to die by age 1 than were children awarded SSI based on other impairments.

Work by Ko and colleagues (2020) used a similar methodological approach and a sample of children continuously enrolled in Medicaid during their first 8 years of life. Results suggest that infants eligible for SSI based on the LBW criteria developed 15 percent fewer chronic health conditions through age 3 relative to a comparison group with birth weights just above the 1200 gram cutoff. The cumulative Medicaid expenditures incurred by eligible infants from birth to age 8 were 23 percent less than those for infants born just above the cutoff. However, work from the state of California by Hawkins and colleagues (2023) found no long-term improvements in educational or labor market outcomes for those who were eligible for SSI based on the LBW criteria relative to a comparison group with birth weights just above the cutoff. According to the authors, the results suggest that “the current level of support targeted to populations endowed with especially high levels of need across multiple dimensions are likely insufficient to achieve the earnings and health gains observed in more advantaged samples” (Hawkins et al., 2023, pp. 5–6).

It is important to note that even among infants automatically eligible for SSI because of birth weight below SSA thresholds, there is less than full take-up, and there is substantial variation in take-up by race, ethnicity, and other markers of disadvantage. Furthermore, there is variation in take-up across counties, suggesting that individuals in some areas may have less access, perhaps as the result of the interaction of structural barriers with existing policy and the support available to potential applicants (Guldi et al., 2023).

FINDINGS AND CONCLUSIONS

Findings

5-1. Evidence increasingly shows that the growth, health, and development of babies born preterm and/or low birth weight (LBW) are impacted by a wide range of medical, educational, and psychosocial factors.

5-2. There are no identified norms for screening and surveillance assessments specific to children born LBW.

5-3. The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) mandates an appropriate public education and provides subsidized special education services for infants, toddlers, children, and youth with disabilities throughout the United States. In many but not all states, infants born LBW are automatically eligible for Early Intervention services under IDEA Part C. Under IDEA Part B, children become eligible for school-based services at 3 years of age and may continue to qualify for such services through age 21.

5-4. States and local entities have their own criteria for children born LBW to qualify for treatments, services, and Early Intervention, as well as benchmarks for time to evaluate and administer treatment, leading to significant variability in receipt of care.

5-5. Families frequently experience systems of care as fragmented and express frustration at having to navigate this complexity with minimal support, which increases the risk that many LBW children will not receive services for which they are eligible.

5-6. If financially eligible, infants with a birth weight under 1200 grams are automatically medically eligible for Supplemental Security Income. (SSI) Infants at higher birth weights may be automatically eligible depending on their gestational age.

5-7. The weight criteria in Social Security Administration’s (SSA’s) LBW listing do not correspond to either the current standard medical definitions of LBW (<2500 grams), very LBW (<1500 grams), or extremely LBW (<1000 grams) or to the percentile cutoffs (10th or 3rd) used by the medical community to identify neonates who are considered small for gestational age (SGA) or severely SGA.

5-8. Infants born SGA are at increased risk of having medical morbidities and developmental delays associated with poor growth of the brain and body.

Conclusions

5-1. The earlier and more sustained a service is, the greater is its long-term impact on growth and development for LBW infants.

5-2. Efficient and timely information transfer from one service system or provider to another is important so that eligibility for services that address issues associated with LBW can be determined as early as possible.

5-3. A birth weight of less than 1500 grams is considered very LBW and is close to the 50th percentile for weight at 32 weeks gestation, after which the risk of severe impairments decreases dramatically.

5-4. Infants who are born SGA (less than the 10th percentile for gestational age) make up an important category of LBW infants born after 32 weeks gestation because their physiology and outcomes are more similar to those of appropriate-weight infants who are born prior to 32 weeks.

5-5. SSI has been shown to improve outcomes for child recipients and their families. There is limited evidence specific to infants eligible for SSI based on the LBW criteria, and this evidence is mixed. Additional research in this area is needed.

REFERENCES

AAP (American Academy of Pediatrics). 2008a. Hospital discharge of the high-risk neonate, from the Committee on Fetus and Newborn. Pediatrics 122(5):1119–1126.

AAP. 2008b. Recommendations for preventive pediatric health care. Pediatrics 2007:2901.

AAP. 2022a. Developmental surveillance and screening. https://www.aap.org/en/patient-care/developmental-surveillance-and-screening-patient-care (accessed July 21, 2023).

AAP. 2022b. Preventive care/periodicity schedule. https://www.aap.org/periodicityschedule (accessed July 21, 2023).

AAP. 2023. Medical home. https://www.aap.org/en/practice-management/medical-home (accessed July 21, 2023).

Acevedo-Garcia, D., N. McArdle, E. F. Hardy, U. I. Crisan, B. Romano, D. Norris, M. Baek, and J. Reece. 2014. The child opportunity index: Improving collaboration between community development and public health. Health Affairs (Millwood) 33(11):1948–1957.

Aizer, A., N. Gordon, and M. Kearney. 2013. Exploring the growth of the child SSI caseload. Disability Research Center paper no. NB13-02. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Aizer, A., H. Hoynes, and A. Lleras-Muney. 2022. Children and the US social safety net: Balancing disincentives for adults and benefits for children. Journal of Economic Perspectives 36(2):149–174.

Antonelli, R. C., and C. Lind. n.d. Care mapping: A how-to guide for patients and families. https://www.childrenshospital.org/sites/default/files/2022-04/integrated-care-mapping-families.pdf (accessed August 7, 2023).

Baggett, K. M., B. Davis, S. H. Landry, E. G. Feil, A. Whaley, A. Schnitz, and C. Leve. 2020. Understanding the steps toward mobile early intervention for mothers and their infants exiting the neonatal intensive care unit: Descriptive examination. Journal of Medical Internet Research 22(9):e18519.

Bailey, M. S., and J. Hemmeter. 2015. Characteristics of noninstitutionalized DI and SSI program participants, 2013 update. https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/rsnotes/rsn2015-02.html (accessed August 7, 2023).

Berman, K., K. Doan, K. Goldfarb, S. Nyman, and O. Wilson. 2022. Advancing preschool inclusion in community-based early childhood education programs. Illinois State Board of Education. Chicago, IL. https://www.isbe.net/Documents/IL-Inclusion-Report.pdf.

Bhaskar, A. R., M. V. Gad, and C. M. Rathod. 2022. Impact of COVID pandemic on the children with cerebral palsy. Indian Journal of Orthopaedics 56(5):927–932.

Boss, R. D., J. C. Raisanen, K. Detwiler, K. Fratantoni, S. M. Huff, K. Neubauer, and P. K. Donohue. 2020. Lived experience of pediatric home health care among families of children with medical complexity. Clinical Pediatrics 59(2):178–187.

Boston Children’s Hospital. 2023. Integrated care at Boston Children’s Hospital—Care mapping. https://www.childrenshospital.org/integrated-care/care-mapping (accessed July 21, 2023).

Brown, T. W., S. E. McLellan, J. A. Scott, and M. Y. Mann. 2022. Introducing the Blueprint for Change: A national framework for a system of services for children and youth with special health care needs. Pediatrics 149(Suppl 7):e2021056150B.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2023a. CDC’s developmental milestones. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/actearly/milestones/index.html (accessed July 10, 2023).

CDC. 2023b. Data and statistics on autism spectrum disorder. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/data.html (accessed July 21, 2023).

CDC. 2023c. What is “Early Intervention”? https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/actearly/parents/states.html (accessed July 31, 2023).

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 2023. Early periodic screening, diagnostic, and treatment. https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/benefits/early-and-periodic-screening-diagnostic-and-treatment/index.html (accessed November 17, 2023).

ChildCare.gov. n.d. Head Start and Early Head Start. https://childcare.gov/consumer-education/head-start-and-early-head-start (accessed July 31, 2023).

Cook, J. T., D. A. Frank, A. F. Meyers, C. Berkowitz, M. M. Black, P. H. Casey, D. B. Cutts, N. Zaldivar, A. Skalicky, S. Levenson, T. Heeren, and M. Nord. 2004. Food insecurity is associated with adverse health outcomes among human infants and toddlers. The Journal of Nutrition 134(6):1432–1438.

Currie, J., and J. Gruber. 1996. Saving babies: The efficacy and cost of recent changes in the Medicaid eligibility of pregnant women. Journal of Political Economy 104(6):1263–1296.

D’Agostino J. A., M. Passarella, P. Saynisch, A. E. Martin, M. Macheras, and S. A. Lorch. 2015. Preterm infant attendance at health supervision visits. Pediatrics 136(4):e794–e802.

Damiano, D. L., and E. Longo. 2021. Early intervention evidence for infants with or at risk for cerebral palsy: An overview of systematic reviews. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology 63(7):771–784.

Davies, P. S., K. Rupp, and D. Wittenburg. 2009. A life-cycle perspective on the transition to adulthood among children receiving Supplemental Security Income payments. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation 30(3):133–151.

Davis, B. E., M. O. Leppert, K. German, C. U. Lehmann, I. Adams-Chapman, Council on Children with Disabilities, and Committee on the Fetus and Newborn.. 2023. Primary care framework to monitor preterm infants for neurodevelopmental outcomes in early childhood. Pediatrics 152(1):e2023062511.

Deshpande, M. 2016. Does welfare inhibit success? The long-term effects of removing low-income youth from the disability rolls. American Economic Review 106(11):3300–3330.

Deshpande, M., and M. Mueller-Smith. 2022. Does welfare prevent crime? The criminal justice outcomes of youth removed from SSI. Quarterly Journal of Economics 137(4): 2263–2307.

DeVoe, J. E., L. Krois, and R. Stenger. 2009. Do children in rural areas still have different access to health care? Results from a statewide survey of Oregon’s food stamp population. Journal of Rural Health 25(1):1–7.

DiNapoli, T. P. 2023. Thousands of young children with disabilities not receiving early intervention service—Audit finds more than half did not receive services to which they were entitled; Black and Hispanic children faced greater barriers. https://www.osc.state.ny.us/press/releases/2023/02/dinapoli-thousands-young-children-disabilities-not-receiving-early-intervention-services (accessed July 21, 2023).

Dobrez, D., A. L. Sasso, J. Holl, M. Shalowitz, S. Leon, and P. Budetti. 2001. Estimating the cost of developmental and behavioral screening of preschool children in general pediatric practice. Pediatrics 108(4):913–922.

DOE (Department of Education). 2011. The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act: Provisions related to children with disabilities enrolled by their parents in private schools. https://www2.ed.gov/admins/lead/speced/privateschools/idea.pdf (accessed October 9, 2023).

Dogruoz Karatekin, B., A. İcagasioglu, S. N. Sahin, G. Kacar, and F. Bayram. 2021. How did the lockdown imposed due to COVID-19 affect patients with cerebral palsy? Pediatric Physical Therapy 33(4).

Duggan, M. G., and M. S. Kearney. 2007. The impact of child SSI enrollment on household outcomes. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 26(4):861–885.

Fenton, T. R., and J. H. Kim. 2013. A systematic review and meta-analysis to revise the Fenton growth chart for preterm infants. BMC Pediatrics 13:59.

Foster, C. C., R. K. Agrawal, and M. M. Davis. 2019. Home health care for children with medical complexity: Workforce gaps, policy, and future directions. Health Affairs (Millwood) 38(6):987–993.

Fraiman, Y. S., J. E. Stewart, and J. S. Litt. 2022. Race, language, and neighborhood predict high-risk preterm infant follow up program participation. Journal of Perinatology 42(2):217–222.

Friedman-Krauss, A. H., and W. S. Barnett. 2023. The state(s) of early intervention and early childhood special education: Looking at equity. New Brunswick, NJ: National Institute for Early Education Research.

GAO (Government Accountability Office). 2012. Supplemental Security Income: Better management oversight needed for children’s benefits. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-12-497 (accessed July 21, 2023).

Goodman-Bacon, A. 2018. Public insurance and mortality: Evidence from Medicaid implementation. Journal of Political Economy 126(1):216–262.

Guldi, M., A. Hawkins, J. Hemmeter, and L. Schmidt. 2022. Supplemental Security Income for children, maternal labor supply, and family well-being: Evidence from birth weight eligibility cutoffs. Journal of Human Resources. https://scholarworks.brandeis.edu/esploro/outputs/9924116689001921 (accessed August 7, 2023).

Guldi, M., A. Hawkins, J. Hemmeter, and L. Schmidt. 2023. Disparities and differential take-up of Supplemental Security Income in Florida: Evidence from birth weight eligibility cutoffs. Preliminary draft, May 16, 2023. www.lucieschmidt.com/s/GHHS_Disparities-and-Differential-Takeup-051623.pdf (accessed January 24, 2024).

Hagan, J. F., J. Shaw, and P. Duncan. 2017. Bright futures. Itasca, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics.

Halfon, N., and C. B. Forrest. 2018. The emerging theoretical framework of life course health development. New York: Springer International Publishing. Pp. 19–43.

Hawkins, A. A., C. A. Hollrah, S. Miller, L. R. Wherry, G. Aldana, and M. D. Wong. 2023. The long-term effects of income for at-risk infants: Evidence from Supplemental Security Income. Working Paper No. 31746. National Bureau of Economic Research. http://www.nber.org/papers/w31746 (accessed January 26, 2024).

Hemmeter, J., and M. Bailey. 2015. Childhood continuing disability reviews and age-18 redeterminations for Supplemental Security Income recipients: Outcomes and subsequent program participation. Research and statistics Note 2015-03. Social Security Administration. https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/rsnotes/rsn2015-03.html (accessed August 7, 2023).

Hemmeter, J., and P. S. Davies. 2019. Infant mortality among Supplemental Security Income applicants. Social Security Bulletin 79(2):51–63.

Hemmeter, J., D. R. Mann, and D. C. Wittenburg. 2017. Supplemental Security Income and the transition to adulthood in the United States: State variations in outcomes following the age-18 redetermination. Social Service Review 91(1):106–133.

HHS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). 2023. Increase the proportion of children who receive a developmental screening—MICH-17. Healthy People 2030. https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/children/increase-proportion-children-who-receive-developmental-screening-mich-17 (accessed July 21, 2023).

HHS and DOE (U.S. Department of Education). 2015. Policy statement on inclusion of children with disabilities in early childhood programs. https://www2.ed.gov/policy/speced/guid/earlylearning/joint-statement-full-text.pdf (accessed January 26, 2024).

Hintz, S. R., J. B. Gould, M. V. Bennett, T. Lu, E. E. Gray, M. A. L. Jocson, M. G. Fuller, and H. C. Lee. 2019. Factors associated with successful first high-risk infant clinic visit for very low birth weight infants in California. Journal of Pediatrics 210:91–98.

Houtrow, A. J., K. Larson, L. M. Olson, P. W. Newacheck, and N. Halfon. 2014. Changing trends of childhood disability, 2001–2011. Pediatrics 134(3):530–538.

Houtrow, A., A. J. Martin, D. Harris, D. Cejas, R. Hutson, Y. Mazloomdoost, and R. K. Agrawal. 2022. Health equity for children and youth with special health care needs: A vision for the future. Pediatrics 149(Supplement 7). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2021-056150F.

Howard, S. W., Z. Zhang, P. Buchanan, E. Armbrecht, C. Williams, G. Wilson, J. Hutchinson, L. Pearson, S. Ellsworth, C. M. Byler, T. Loux, J. Wang, S. Bernell, and N. Holekamp. 2017. The effect of a comprehensive care transition model on cost and utilization for medically complex children with cerebral palsy. Journal of Pediatric Health Care 31(6): 634–647.

HRSA (Health Resources and Services Administration). 2022. Children and youth with special health care needs. HRSA Maternal and Child Health Bureau. https://mchb.hrsa.gov/programs-impact/focus-areas/children-youth-special-health-care-needs-cyshcn (accessed August 7, 2023).

KFF. 2021. Percent of children with a medical home. https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/children-with-a-medical-home (accessed July 21, 2023).

Kim, S.-Y., and A. R. Kim. 2022. Attachment- and relationship-based interventions during NICU hospitalization for families with preterm/low-birth weight infants: A systematic review of RCT data. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19(3):1126.

Ko, H., R. Howland, and S. Glied. 2020. Supplemental Security Income improves the health of very low birth weight babies and reduces Medicaid costs: Evidence from New York. SSRN 4202332.

Kose, E., S. M. O’Keefe, and M. Rosales-Rueda. 2022. Does the delivery of primary health care improve birth outcomes? Evidence from the rollout of community health centers. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Kuo, D. Z., J. W. McAllister, L. Rossignol, R. M. Turchi, and C. J. Stille. 2018a. Care coordination for children with medical complexity: Whose care is it, anyway? Pediatrics 141(Suppl 3): S224–S232.

Kuo, D. Z., C. Ruud, and D. C. Tahara. 2018b. Achieving care integration for children with medical complexity: The human-centered design approach to care coordination. Palo Alto, CA: Lucile Packard Foundation for Children’s Health.

Landa, R. J. 2018. Efficacy of early interventions for infants and young children with, and at risk for, autism spectrum disorders. International Review of Psychiatry 30(1):25–39.

Lichstein, J. C., R. M. Ghandour, and M. Y. Mann. 2018. Access to the medical home among children with and without special health care needs. Pediatrics 142(6). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-1795.

Lipkin, P. H., and M. M. Macias. 2020. Promoting optimal development: Identifying infants and young children with developmental disorders through developmental surveillance and screening. Pediatrics 145(1). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-3449.

Litt, J. S., and D. E. Campbell. 2023. High-risk infant follow-up after NICU discharge: Current care models and future considerations. Clinics in Perinatology 50(1):225–238.

Maenner, M. J., Z. Warren, A. Robinson Williams, E. Amoakohene, A. Bakian, D. Bilder, M. Durkin, R. Fitzgerald, S. Furnier, M. Hughes, C. Ladd-Acosta, D. McArthur, E. Pas, A. Salinas, A. Vehorn, S. Williams, A. Esler, A. Grzybowski, J. Hall-Lande, R. Nguyen, K. Pierce, W. Zahorodny, A. Hudson, L. Hallas, K. Clancy Mancilla, M. Patrick, J. Shenouda, K. Sidwell, M. DiRienzo, J. Gutierrez, M. Spivey, M. Lopez, S. Pettygrove, Y. Schwenk, A. Washington, and K. Shaw. 2023. Prevalence and characteristics of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years—Autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2020. MMWR Surveillance Summaries 72:1–14.

Matoba, N., M. Reina, N. Prachand, M. M. Davis, and J. W. Collins. 2019a. Neighborhood gun violence and birth outcomes in Chicago. Maternal and Child Health Journal 23(9):1251–1259.

Matoba, N., S. Suprenant, K. Rankin, H. Yu, and J. W. Collins. 2019b. Mortgage discrimination and preterm birth among African American women: An exploratory study. Health Place 59:102193.

MCHB (Maternal and Child Health Bureau). 2023. Blueprint for Change. Health Resources and Services Administration. https://mchb.hrsa.gov/programs-impact/focus-areas/children-youth-special-health-care-needs-cyshcn/blueprint-change (accessed October 9, 2023).

McLellan, S. E., M. Y. Mann, J. A. Scott, and T. W. Brown. 2022. A Blueprint for Change: Guiding principles for a system of services for children and youth with special health care needs and their families. Pediatrics 149(Supplement 7):e2021056150C.