Low Birth Weight Babies and Disability (2024)

Chapter: 2 Contributors to and Trends in Morbidity, Mortality, and Survivability among Low Birth Weight Infants

2

Contributors to and Trends in Morbidity, Mortality, and Survivability among Low Birth Weight Infants

Approximately 3.6 million live births occur in the United States each year; the annual birth rate has decreased overall after peaking in 2007 (Hamilton et al., 2023; Martin et al., 2010). About 10 percent of these annual births are preterm (Hamilton et al., 2023; Osterman et al., 2023), defined as a pregnancy leading to delivery at less than 37 weeks gestational age (WHO, 2023). The percentage of children born with low birth weight (LBW), defined by the medical community as less than 2500 grams (5.5 pounds) at birth (WHO, 2015), is between 8 and 9 percent, and in 2021 was 8.52 percent (Osterman et al., 2023). This chapter provides an overview of factors contributing to LBW and preterm birth, describes the professionally accepted clinical standards for defining gestational age as well as LBW and preterm births, presents data on survivability among LBW and preterm babies over the past 20 years and on morbidity and trends in the occurrence of long-term health effects, and gives an overview of advances in interventions in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) for infants born LBW or preterm and their parents.

CONTRIBUTORS TO LOW BIRTH WEIGHT

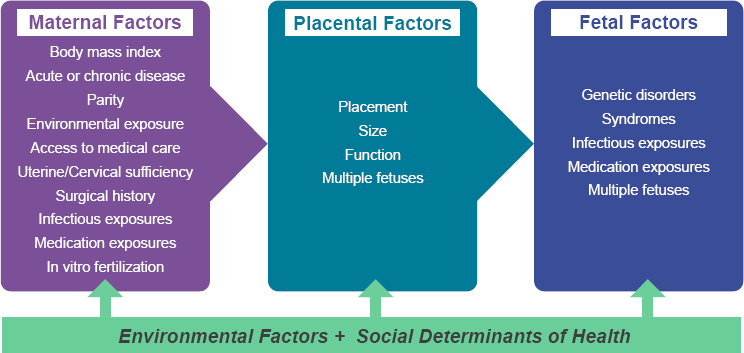

Contributors to LBW include preterm birth and maternal, fetal, placental, and environmental factors. Villar and colleagues (2012) propose a prototype phenotypic classification for the factors or domains that could impact gestational age and birth weight. The first domain includes maternal conditions, such as infections; trauma; chronic diseases; and pregnancy complications, such as eclampsia. The second domain comprises significant fetal conditions resulting from, for example, intrauterine growth restriction,

fetal anomalies, and multiple gestations. The third domain focuses on placental conditions affecting fetal growth or gestational age (Figure 2-1).

In addition to these domains, it is recognized that one’s physical environment and socioeconomic circumstances are associated with preterm birth. In particular, consistent data demonstrate an association between higher levels of air pollution and preterm birth (Bekkar et al., 2020). This environmental exposure may affect preterm birth through effects on the mother, but also potentially on the placenta (Basilio et al., 2022). Importantly, disparities in social determinants of health (SDOH), including race and ethnicity, driven by structural racism, also have been found to be associated with rates of preterm birth and fetal growth restriction (Bryant et al., 2010). Environmental and socioeconomic factors affecting preterm birth and LBW are interrelated. A study of the impact of air pollution on preterm birth showed a greater negative impact on Black and Hispanic compared with White populations (Dzekem et al., 2023). And in a study of redlining of neighborhoods in New York state, living in historically redlined versus nonredlined neighborhoods was associated with an increased risk of preterm birth (Dzekem et al., 2023; Hollenbach et al., 2021).

PROFESSIONALLY ACCEPTED STANDARDS DEFINING LOW BIRTH WEIGHT AND PRETERM INFANTS

Clinical Standards for Determining Gestational Age

The physiology of a newborn infant is often determined by gestational age: the younger the infant is in gestational age, the more adverse is the

infant’s physiology or functioning of the organs, especially the lungs, brain, circulatory system, and intestines. To best facilitate care after delivery, it is important to accurately determine and optimize dating estimates based on an assessment of the newborn infant. Although both estimated fetal weight and birth weight are associated with gestational age, neither can be used clinically to estimate gestational age. There are several standard measures for determining gestational age prenatally, including maternal reporting of the date of the last menstrual period, fundal height measurement, and ultrasonography. Gestational age in weeks and days is determined most accurately using the date of the last menstrual period in combination with a first-trimester (<14 weeks) ultrasound, termed the best obstetrical estimate of gestational age. This combination has a high degree of accuracy, providing an estimated due date within 5–7 days of the date of birth. Ultrasound dating after the first trimester can vary by as much as 21–30 days, depending on the timing of the ultrasound and its correlation with the date of the last menstrual period (ACOG, 2017). At present, ultrasonography during the first trimester of pregnancy is the best method for determining gestational age (ACOG, 2017; Naidu and Fredlund, 2023). Postnatally, two methods are used to assess gestational age in the newborn: the New Ballard Maturational Assessment (more commonly referred to as the New Ballard exam), which estimates gestational age within 2 weeks (Ballard et al., 1991; Donovan et al., 1999), and the Dubowitz Clinical Assessment (Dubowitz et al., 1970).

Low Birth Weight, Preterm, and Small for Gestational Age

As described in Chapter 1, infants born LBW (<2500 grams) comprise three general groups: those born preterm (<37 weeks gestational age); those born small for gestational age (SGA) (<10th percentile for gestational age [Murray and Richardson, 2017]); and those born both preterm and SGA. The medical community recognizes divisions within the LBW and preterm categories (see Box 1-2 in Chapter 1).

Although survival among preterm infants has improved in all gestational age categories, rates of both in-hospital and long-term morbidity among these infants do not appear to have improved appreciably (Bell et al., 2022; Younge et al., 2017). Their rates of cognitive impairment, behavioral impairment, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, autism spectrum disorder, and cerebral palsy, as well as chronic health conditions, such as hearing impairment, vision loss, chronic lung disease, asthma, epilepsy, the need for gastrostomy tube feedings, and tracheostomy, are elevated compared with their term counterparts. These morbidities are apparent in infancy; early, middle, and late childhood; and adulthood (Busque et al., 2022; Orchinik et al., 2011).

Similarly, there are risks associated with being born SGA (Goldstein et al., 2017; Murray and Richardson, 2017). Children born SGA, especially

when restricted beyond genetic prediction, are at increased risk of having medical morbidities and developmental delays associated with poor growth of the brain and body (Sacchi et al., 2020). Maternal, placental, congenital, infectious, and genetic factors are common etiologies of fetal growth restriction that can result in SGA newborns (Sharma et al., 2017).

CURRENT SURVIVABILITY RATES

Although estimates of survival can be based on birth weight, in the 21st century it is more common to consider survival rates based on gestational age. The reverse of survival is mortality, captured in the mortality indices available through the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). Assessing current rates of survivability among LBW infants is a medically complex issue. The committee acknowledges the role of such factors as congenital and genetic abnormalities in morbidities and mortality for this population. However, for the purposes of this report, the committee chose to examine only survivability based on gestational age and birth weight as outlined in the statement of task (Box 1-1 in Chapter 1). The infant mortality rate (IMR) for infants classified as “short gestation and low birth weight, not elsewhere classified” decreased in the United States over time between 2010 and 2021 (Table 2-1). Although the IMR has trended downward since

| Year | Infant Mortality Rate |

|---|---|

| 2021 | 80.7 |

| 2020 | 87.2 |

| 2019 | 92.3 |

| 2018 | 97.1 |

| 2017 | 97.4 |

| 2016 | 99.5 |

| 2015 | 102.7 |

| 2014 | 104.6 |

| 2013 | 107.1 |

| 2012 | 106.6 |

| 2011 | 104.1 |

| 2010 | 103.8 |

SOURCE: Ely and Driscoll, 2023, Table 3.

| Year | Less Than 32 Weeks | 32–33 Weeks | 34–36 Weeks | 37–41 Weeks | 42 Weeks or More |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 167.39 | 19.35 | 8.11 | 2.08 | 3.79 |

| 2020 | 175.88 | 20.11 | 7.92 | 2.04 | 4.17 |

| 2019 | 180.40 | 19.21 | 8.21 | 2.03 | 5.72 |

| 2018 | 185.79 | 21.95 | 8.21 | 2.05 | 5.39 |

| 2017 | 187.56 | 20.50 | 8.50 | 2.10 | 3.98 |

| 2016 | 190.15 | 20.12 | 8.65 | 2.19 | 4.31 |

| 2015 | 193.54 | 20.79 | 8.76 | 2.17 | 4.20 |

SOURCE: Ely and Driscoll, 2023, p. 5.

1995 (the first year of linked infant birth/death data), it remained essentially the same between 2020 and 2021 (5.42/1,000 live births in 2020 versus 5.44/1,000 in 2021) (Ely and Driscoll, 2023). Preterm birth and LBW remained the second leading cause of death among infants, accounting for 15 percent of infant deaths in 2021, down from 16 percent in 2020 (Ely and Driscoll, 2023; Murphy et al., 2021, “data table for Figure 5”), as well as significant morbidity and mortality among survivors.

Additionally, mortality rates decreased as gestational age increased, up to 41 weeks. From 2015 to 2021, infant mortality decreased across all gestational age groups, from <32 to 41 weeks. Among LBW infants, evaluated by gestational age, rates were as low as 0.8 percent for those born at 34–36 weeks and as high as 17 percent for those born at less than 32 weeks (Table 2-2).

Similarly, considering the IMR by birth weight shows decreased mortality in the LBW and very LBW categories over the 21-year period from 2000 to 2021 (Table 2-3). Consistent with improved survival at greater gestational ages, these data also show significantly improved survivability among infants born at 1500–2499 grams compared with those born at less than 1500 grams.

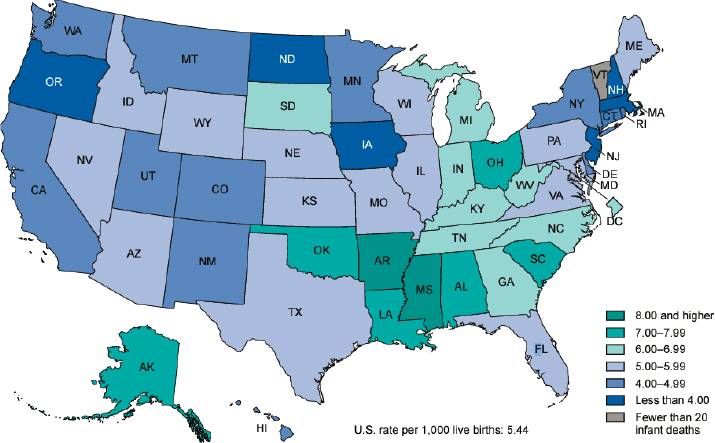

State and local differences in infant mortality rates are also available from NCHS (Figure 2-2). In 2021, the IMR in the United States was 5.44 per 1,000 live births (Ely and Driscoll, 2023). Twenty-five states had an IMR higher than the national rate, ranging from 5.45 in Wyoming to 9.39 in Mississippi (Ely and Driscoll, 2023, Table 5). Sixteen states had an IMR of 6.0 or greater. State and local resources for access to prenatal, perinatal, and neonatal care, as well as differences in access to services such as early intervention, likely contribute to the differences in infant mortality and outcomes among states (Brown et al., 2020; Friedman-Krauss and Barnett, 2023; Hirai et al., 2018; March of Dimes, 2023; Pineda et al., 2023; Radley

| Year | <1500 | 1500–2499 | <2500 | >=2500 | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 187.90 | 12.97 | 41.78 | 2.00 | Ely and Driscoll, 2023, Table 2 |

| 2020 | 198.38 | 12.49 | 43.15 | 1.98 | Ely and Driscoll, 2022, Table 2 |

| 2019 | 203.52 | 12.75 | 44.90 | 1.97 | Ely and Driscoll, 2021, Table 2 |

| 2018 | 204.07 | 13.26 | 45.89 | 1.99 | Ely and Driscoll, 2020, Table 2 |

| 2017 | 208.91 | 13.17 | 46.84 | 2.03 | Ely and Driscoll, 2019, Table 2 |

| 2016a | 2.09 | CDC, 2016 Table 3 | |||

| 2015a | 2.05 | CDC, 2015, Table 2 | |||

| 2014a | 2.00 | CDC, 2014, Table 2 | |||

| 2013 | 219.56 | 13.41 | 50.26 | 2.05 | Mathews et al., 2015, Table 1 |

| 2012a | 2.07 | CDC, 2012, Table 2 | |||

| 2011a | 2.08 | CDC, 2011, Table 2 | |||

| 2010 | 222.15 | 13.42 | 50.98 | 2.13 | Mathews and MacDorman, 2013a, Table 1 |

| 2009 | 231.23 | 13.83 | 53.02 | 2.21 | Mathews and MacDorman, 2013b, Table 1 |

| 2008 | 237.39 | 14.31 | 54.53 | 2.29 | Mathews and MacDorman, 2012, Table 1 |

| 2007 | 240.88 | 14.62 | 56.12 | 2.29 | Mathews and MacDorman, 2011, Table 1 |

| 2006 | 240.44 | 14.11 | 55.38 | 2.24 | Mathews and MacDorman, 2010, Table 1 |

| 2005 | 244.95 | 14.73 | 57.39 | 2.3 | Mathews and MacDorman, 2008, Table 1 |

| 2004 | 244.5 | 14.97 | 57.64 | 2.26 | Mathews and MacDorman, 2007, Table, 1 |

| 2003 | 252 | 15 | 59.04 | 2.29 | Mathews and MacDorman, 2006, Table 1 |

| 2002 | 250.8 | 15.1 | 59.5 | 2.4 | Mathews et al., 2004, Table 1 |

| 2001 | 244.4 | 15.2 | 58.6 | 2.4 | Mathews et al., 2003, Table 1 |

| 2000 | 244.3 | 15.8 | 59.4 | 2.5 | Mathews et al., 2002, Table 2 |

a Some data are unavailable for these years within these categories

et al., 2023). Federal programs and guidelines improve the equitable distribution of resources among states.

As described in Chapter 1, minoritized race and ethnicity have been associated with adverse birth outcomes, as reflected in the higher IMR in

SOURCE: Ely and Driscoll, 2023.

minoritized communities in the United States (Almeida et al., 2018; Ely and Driscoll, 2023; Hill et al., 2022; Jang and Lee, 2022; Kennedy-Moulton et al., 2022; Ro et al., 2019). In addition, as explained in Chapter 1, race must be considered not as a determinative variable in and of itself, but as a proxy for environmental and social factors that disproportionately affect these groups, including structural racism, various environmental exposures, and difficulties with health care access (Borrell et al., 2021; Boyd et al., 2020). Accordingly, it is important to develop interventions thoughtfully and with consideration of the larger influences informing racial differences.

OCCURRENCE OF LONG-TERM HEALTH EFFECTS AMONG CHILDREN BORN AT LOW BIRTH WEIGHT

Among deliveries at early gestational ages, the risk for disability appears to increase as gestational age increases from 22 to 28 weeks because the survival rate increases. Thus, it is critical to examine the rates of disability among survivors, which decrease and continue to decrease throughout this gestational age range. Survival without disability increases from 23 percent at 22 weeks to 71 percent at 27 weeks (Myrhaug et al., 2017). Among preterm births, the highest risk of morbidity and mortality is for those born at less than 32 weeks and 1500 grams (Khasawneh and Khriesat, 2020).

Mild, moderate, and severe impairments are identified using cognitive, motor, social, sensory, educational, and functional measures that are validated at different ages in infancy and childhood (see Chapters 3 and 4). Although cognitive, motor, behavioral, and functional/school outcomes improve as gestational age increases (Bhutta et al., 2002), outcomes vary within each gestational age category based on the nature and severity of the associated health condition(s). Although morbidity is inversely proportional to gestational age, all preterm and LBW neonates have increased rates of short- and long-term morbidities (Saigal and Doyle, 2008). Additionally, these outcomes correspond to brain volumes and connectivity, which can be measured as late as adolescence (de Jong et al., 2012; Ma et al., 2022). Differential health and developmental outcomes can be measured through adulthood.

Infants born at 22–28 weeks gestational age are the group of preterm neonates most rigorously studied by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Neonatal Research Network (NRN, n.d.; SUPPORT Study Group of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD Neonatal Research Network, 2010). Although the overall survival rate for this age group is now 78 percent, the rate of moderate to severe neurodevelopmental impairment (NDI) is 50 percent (Bell et al., 2022). Moderate NDI is defined as greater than 1 standard deviation below normative values for the Bayley-III cognitive or motor composite scores, or level 2 or 3 on the Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS) at 22–26 months adjusted age. Severe NDI is defined as 2 standard deviations below the normative values for the Bayley-III motor or cognitive composite scores, level 4 or 5 on the GMFCS, and/or bilateral blindness or bilateral severe functional hearing impairment (Bell et al., 2022).

There is some evidence that survival without NDI has improved over time among infants born extremely LBW and/or extremely preterm. Wilson-Costello and colleagues (2007) compared survival and morbidity among extremely LBW infants in their institution across three time periods (1982–1989, 1990–1999, and 2000–2002). They found an increase in survival (49 percent compared with 68 percent) between the first two time periods, but also an increase in morbidity (i.e., increased survival with impairment). In contrast, they found no increase in survival between the second and third time periods, but decreased morbidity. For example, the rate of cerebral palsy, which increased from 8 to 13 percent between the first two time periods, dropped to 5 percent in the third. Similarly, the overall rate of NDI, which included neurosensory abnormalities and/or subnormal scores on the Bayley mental development index, increased from 28 to 35 percent between the first two time periods, then dropped to 23 percent in the third (Wilson-Costello et al., 2007). Similarly, a cohort study of extremely preterm infants found that survival without major NDI increased from 42 to 62 percent

between 1991–1992 and 2016–2017 (Cheong et al., 2021). Another study comparing survival and morbidity among infants born extremely preterm (22–24 weeks) between 1998–2004 and 2005–2011 found a decrease in mortality (from 55 to 42 percent) and in NDI (from 68 to 47 percent) between the two time periods (Younge et al., 2016). Late-onset sepsis, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, and surgical necrotizing enterocolitis also were seen less often during the later time period (Younge et al., 2016). In contrast, in a population-based cohort of very preterm infants in Nova Scotia, while infant mortality decreased from 25.6 percent in 1993 to 11.4 percent in 2002, the rate of cerebral palsy increased from 4.4 to 10 percent during the same period (Vincer et al., 2006).

Infants with structural abnormalities—including congenital anomalies such as omphaloceles/gastroschisis, trachea-esophageal fistula, congenital diaphragmatic hernia, VACTERL syndrome, and Pierre-Robin syndrome, as well as renal, cardiac, and other anomalies associated with LBW, SGA, and at times postnatal growth restriction—are at high risk for morbidity and mortality and require significant high-end medical and multiple surgical interventions, leading to multiple hospitalizations and multidisciplinary follow-up visits. For example, SGA infants are twice as likely to be born with congenital heart disease (CHD), which is associated with increased mortality rates, developmental disorders, disabilities, and delay (Costello and Bradley, 2021; Lisanti et al., 2023). Given these risks, SGA infants with suspected CHD may be tested using pulse oximetry, electrocardiogram (ECG or EKG), echocardiogram, chest X-ray, cardiac catheterization or heart magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Mayo Clinic, n.d.). If CHD is confirmed, surgical intervention is required to correct the abnormality, and subsequent high-risk follow-up care is administered. In addition, many known and as yet unknown genetic disorders are associated with SGA, which can also be associated with multiple morbidities requiring multidisciplinary interventions and follow-up visits with specialists, along with multiple hospitalizations. Finally, babies born with metabolic disorders suffer postnatal growth restriction and require standard and novel interventions that must also be considered in this context.

ADVANCES IN PREVENTION OF AND ACUTE MEDICAL CARE FOR LOW BIRTH WEIGHT AND PRETERM BIRTH AND IMPROVED OUTCOMES

Advances in Prenatal Care

A number of advances in care for pregnant people have reduced perinatal mortality overall and rates of preterm and LBW birth. Certain high-risk maternal conditions confer an increased risk of preterm birth, and improved

management of these conditions has reduced the risk of experiencing such a birth. For example, the 2022 CHAP (Chronic Hypertension and Pregnancy) trial found a reduction in preeclampsia and preterm birth with better blood pressure control (Tita et al., 2022). Routine use of low-dose aspirin also can reduce the risk of preterm birth in individuals at increased risk of preeclampsia and is recommended by the United States Preventive Services Task Force (Davidson et al., 2021; Henderson et al., 2021). Other approaches have led to a reduction in perinatal mortality among neonates. For example, universal screening for group B streptococcus has led to a reduction in neonatal sepsis (Clifford et al., 2012). Additionally, maternal vaccination for influenza leads to a reduction in preterm birth, and maternal vaccination for pertussis reduces the risk of pertussis infection in infants (ACOG, 2018b; Skoff et al., 2023).

For patients at increased risk of preterm birth, a number of interventions have produced evidence for improved perinatal mortality or morbidity. Several large trials, for example—the largest in the United States—have examined the use of antenatal magnesium sulfate to reduce the risk of neonatal morbidity (Rouse et al., 2008). Since a systematic review demonstrated its overall benefit (Nguyen et al., 2013), antenatal magnesium sulfate has been used routinely. Antenatal corticosteroids given to pregnant persons at increased risk of preterm birth have been used for about 50 years to reduce morbidity and mortality (Wapner et al., 2016). Initially, this approach was applied to pregnancies at 24–34 weeks gestation, but the approach has been refined to reflect evidence generated by research over the past two decades. Several studies now support the use of a second course of antenatal corticosteroids in ongoing, at-risk pregnancies (Walters et al., 2022). Recently, a trial examining the use of antenatal corticosteroids from 34 0/7 to 36 6/7 weeks gestation found benefit in reducing morbidity among offspring (Gyamfi-Bannerman et al., 2016).

The broad approach used to reduce the incidence of preterm birth has had less success. Tocolytics have been a mainstay of efforts to prevent preterm birth in people with preterm labor, but consistent evidence demonstrates only a delay in birth of 48 hours to up to 7 days (Wilson et al., 2022). In people with a prior preterm birth, the current approach involves using ultrasound for cervical length screening and treating those with a short cervix with vaginal progesterone, cerclage, or both (Aubin et al., 2023).

Although advances in medical interventions play a vital role in reducing perinatal mortality and instances of LBW or preterm birth, it is important to recognize that nonmedical interventions can play a role in birth outcomes. Nonmedical interventions, such as group prenatal services and the use of community-based health workers including doulas, have been linked to advances in prenatal, perinatal, and postnatal care, as well as to reduced instances of LBW and preterm birth and decreased morbidity

and mortality among infants born LBW or preterm. Financial support, for example, such as the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and increases in state minimum wages, are associated with improved prenatal, perinatal, and postnatal care and with reduced disparities in birth outcomes. One study that examined the effects of state-level EITC laws on birth outcomes revealed that as the state EITC increased, so did improvements in birth outcomes. Specifically, in states with the most generous EITC levels, African American mothers experienced reductions in the risk of LBW birth, as well as increased duration of gestation (Komro et al., 2019). State minimum wage increases also are associated with reduced instances of LBW. Results published by Komro and colleagues (2016) illustrate how a single U.S. dollar increase in the minimum wage at the federal level reduced instances of LBW by up to 2 percent. Similarly, in a more recent analysis examining the effects of the minimum wage on infant health, the researchers found that a single U.S. dollar increase in the minimum wage at the federal level yielded a statistically significant increase in birth weight, fetal growth rate, and gestation length (Wehby et al., 2020).

According to a review of recent literature conducted by the Kaiser Family Foundation, state Medicaid expansion is associated with increases in health care access, health care utilization, and maternal and infant health outcomes, including the improvements in infant birth outcomes such as LBW (Everitt et al., 2022; Guth and Diep, 2023). Children born LBW can experience a wide array of medical complexities. Home care services, varying widely based on the needs of the infant and family, may also be a crucial support for child health and survival and overall family stability and wellbeing (Boss et al., 2020). In addition, community-based health workers contribute to advances in prenatal care. For example, doula-assisted mothers were found to be four times less likely to give birth to an LBW infant compared with non–doula-assisted mothers (Gruber et al., 2013). Furthermore, Straughen and colleagues (2023) found that urban area African American pregnant women who enrolled in a community-based health worker program were less likely to give birth to children admitted to the NICU and reported overall improved psychosocial health.

Fetal intervention and NICU consultation programs also have increased across the United States. Pregnant people now have greater access to surgeons who perform early procedures, such as ablation for twin–twin transfusion, that often lead to early delivery (Zaretsky et al., 2019). Obstetrics and neonatal teams partner to create pathways for resuscitation, at the border of viability, often allowing resuscitation, a procedure that used to be rare, at younger gestational ages, such as 22–23 weeks. As discussed earlier, while such interventions lead to greater survivability, there is a concurrent increase in morbidity among these infants because of the high rate of long-term neurodisability.

Postpartum Care for Birthing Parents

The immediate postpartum period (12–13 weeks following birth) has been described as the fourth trimester, reflecting the ongoing needs of all postpartum parents and their infants. It is a crucial time for recovery, medical treatment, psychosocial adjustment, and planning for constraints faced peripartum and thereafter. The impact of resources to support families during this time cannot be overstated (ACOG, 2018a; Lubker Cornish and Roberts Dobie, 2018; Savage, 2020). A recent study demonstrated an association between expansion of family leave coverage for the postpartum period and a reduction in infant mortality (Montoya-Williams et al., 2020). In addition, many delivering parents of LBW infants may themselves require more medical intervention compared with parents of children born at term—for maternal hypertension/pre-ecclampsia, for example, which may result in hospitalization and additional medical costs.

NICU Care

Most children born LBW require more than average medical services, including services based in the hospital, often in the NICU, and primary or specialty care settings. Preterm infants receive specific services in the NICU, such as initial stabilization, growth and developmental assessments, and determination of risk factors. In addition to life-saving interventions, including respiratory and nutritional support, routine screening may take place in the NICU, such as ultrasounds for intracranial hemorrhage and periventricular leukomalacia, vision screening, and hearing screening. These assessments may also lead to further consultation with in-house specialty care providers and therapists, who may address growth and feeding and other specific medical needs. Findings in the NICU may lead to additional service tracks, including treatments that start in the NICU and have specific follow-up pathways.

Within the NICU, dedicated care tracks, such as small-baby programs (Banerji et al., 2022), have emerged to target the medical and developmental needs of LBW children generally. Such programs entail population definition, space planning, and standardized care, including development promotion. Additionally, specialized interventions in the medical setting may be available for certain identified medical complications, including cerebral palsy (AACPDM, 2023).

Although there are no strict national guidelines or protocols for NICU care for infants born LBW or preterm, care in the NICU generally includes standard processes for resuscitation, such as that mentioned above at the border of viability; care for thermoregulation; ventilation; electrolyte, fluid, and weight management; and developmental and parental engagement. The American Academy of Pediatrics has also published standards that propose a baseline of components that should be included in neonatal care programs

at every level, ranging from special care nurseries (Level I) to complex subspecialty care services (Level IV) (Stark et al., 2023).

Advances in care that led to increased survival by the mid- to late 1990s among infants born very and extremely preterm include enhanced assisted ventilation, the introduction of surfactant, and the use of antenatal and postnatal corticosteroids (Cheong et al., 2021; Saigal and Doyle, 2008; Wilson-Costello et al., 2007). However, some advances in treatment, including, for example, mechanical ventilation and the use of postnatal steroids, also contributed to iatrogenic injury and adverse outcomes among survivors (Kang et al., 2022; Vincer et al., 2006; Wilson-Costello et al, 2007). In the past two decades, advances in neonatal care have focused on improving outcomes for children born preterm while maintaining or improving survival. Such advances include, for example, routine use of antenatal steroids and reduction in postnatal steroid use; shortened duration of mechanical ventilation, along with use of noninvasive ventilation, such as nasal continuous positive airway pressure or nasal intermittent positive pressure ventilation; use of antenatal magnesium sulfate for fetal neuroprotection; sepsis prevention initiatives; and management of blood pressure fluctuations to reduce rates of intraventricular hemorrhage (Cheong et al., 2021; Fathi et al., 2022; Kang et al., 2022; Payne et al., 2010; Shennan et al., 2021; Wilson-Costello et al., 2007). Advances in diagnosis and treatment of prematurity-related diseases have improved control of infection, seizures, intraventricular hemorrhage, necrotizing enterocolitis, patent ductus arteriosus, retinopathy of prematurity, and hearing loss (Kang et al., 2022; Patel, 2016; Pavel et al., 2022; Talavera et al., 2016; Vesoulis and Mathur, 2014; Wilson-Costello et al., 2007). Improved ventilation and medical management for respiratory distress have decreased respiratory insufficiency and bronchopulmonary dysplasia or chronic lung disease. And the use of specialized intravenous and enteral nutrition and advances in infection control have improved nutrition and infection prevention in LBW infants.

There is some evidence on the longer-term effects of medical interventions for very LBW infants (<1500 grams). For example, Chyn and colleagues (2021) found that infants just under 1500 grams were receiving more intense care in the hospital, seeing higher test scores in elementary and middle school, experiencing a 32 percent increase in the probability of college enrollment, and incurring a roughly $66,000 reduction in social program expenditures by age 14 compared with those born just above the 1500 gram threshold.

NICU-Based Programs for Neurodevelopmental Care

Complementing advances in medical interventions, hospital-based modifications in environments and specific developmental interventions to

promote optimal neonatal development have improved care and outcomes for LBW infants. Such modifications and interventions include implementation of kangaroo care; minimized handling of extremely LBW infants by medical staff through a reduction in the frequency of routine assessments and unnecessary cuff blood pressure measurements; reduction of direct lighting; increased involvement of parents in the day-to-day care of their infant, including breast feeding; and single rooms, although the opportunity for human interaction when developmentally appropriate appears to be more important than the nature of the physical space (Fathi et al., 2022). Interventions, both in the NICU and soon after discharge, involving physical, occupational, and feeding therapy, including positioning, movement, and massage, also have contributed to improved outcomes (Khurana et al., 2020; Séassau et al., 2023). Early neurodevelopmental testing, which can include generalized movement assessment and other early-detection tools for cerebral palsy, is important for both early detection and targeted intervention. As mentioned previously, specialized care interventions, such as bronchopulmonary dysplasia and small-baby programs, use specialized training and teams to improve outcomes (Banerji et al., 2022; Fathi et al., 2022; Sanlorenzo and Hatch, 2023; Shepherd et al., 2012). Family-centered rounds and care routines, including giving parents/caregivers broad access to their infants, encourage bonding and family involvement in caring for the child (Fathi et al., 2022).

Discharge Coordination for LBW Infants

Careful coordination of discharge for LBW infants optimizes care for their medical conditions and developmental trajectories, and includes education and training for parents providing care once the infant goes home (AAP, 2008; Smith, 2022). Multidisciplinary screening and evaluation of body systems before discharge (e.g., screening for congenital heart disease, auditory and retinopathy of prematurity testing, newborn blood testing for preventable diseases) are essential to a safe transition home (Smith, 2022). Many LBW infants will need home-based equipment and technology, such as oxygen, feeding tubes, and monitoring devices, that require careful coordination. Case management and social work teams provide valuable support for many families by helping them navigate public benefit programs such as Medicaid, Early Intervention, Supplemental Security Income, and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) and the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC). Coordination of discharge appointments, such as those for primary care and subspecialty care, decreases readmission to the hospital and minimizes postdischarge morbidity. Chapter 5 provides an overview of the availability and delivery of treatments, services, and resources following NICU discharge.

NEONATAL RESEARCH NETWORKS AND PROGRAMS SUPPORTING LBW INFANTS

The NICHD has provided guidance and funding for neonatal care in the United States since 1962. The NICHD Neonatal Research Network, which currently consists of 16 sites, develops research protocols “to investigate the safety and efficacy of treatment and management strategies for newborn infants” and “to provide evidence to guide clinical practice for critically ill newborns” (NRN, n.d.). Similarly, EPICure and Epipage are longitudinal cohort studies of babies born in the United Kingdom and France, respectively, with the goal of improving care and outcomes for children born preterm (Costeloe and EPICure Study Group, 2006; EGA Institute for Women’s Health, n.d.; Pierrat et al., 2021; Republique Francaise, n.d.). Short- and long-term morbidities persist even as survival rates improve for infants born preterm or LBW, especially among those born very preterm or very LBW. Some life-saving interventions, such as respiratory support, are necessary for survival but carry the risk of damaging the lungs, brain, eyes, and other organs (Cannavò et al., 2020; Kang et al., 2022; Lin et al., 2022). Life-saving interventions may be modified or new ones studied with the goal of reducing adverse secondary effects, while maintaining or improving survival (see, e.g., Schulzke and Stoecklin [2022] for updates on ventilatory management of extremely preterm infants).

States provide codes and rules to support hospital operations and care involving obstetrics and neonatal/follow-up practices. Level III and IV NICUs offer follow-up programing that often includes medical and developmental supports for LBW infants, who undergo sequential developmental testing and surveillance for delays and diagnosis as appropriate. The NICU/developmental evaluation clinics ensure appropriate family and infant involvement in early intervention or therapy, depending on the needs of the infant and family. It should be noted, however, that not all infants born LBW and their families have access to these essential follow-up services because of barriers resulting from social inequities in health and health care. In addition, access to high-level NICUs is often limited based on region, with many families having no easy access to intensive care. Further, state-level guidelines vary regarding the NICU level of care and access to high-risk follow-up clinics.

FINDINGS AND CONCLUSIONS

Findings

2-1. Accurately determining gestational age in weeks is important because of the relationship of gestational age to morbidity, mortality, and functioning among LBW infants.

2-2. Gestational age in weeks and days is determined most accurately using the date of the last menstrual period in combination with a first-trimester ultrasound (until 13 6/7 weeks), providing an estimated due date within 5–7 days of delivery.

2-3. Current medical practice relies on gestational age rather than birth weight to inform medical and developmental prognosis.

2-4. The physiology of a newborn infant is often determined by gestational age: the younger the infant in gestational age, the more immature is the infant’s physiology and the more adverse is the functioning of the infant’s organs, especially the lungs, brain, circulatory system, and intestines.

2-5. Among infants born preterm, survival has improved in all gestational age categories over the past 20 years. However, socioeconomic and racial/ethnic disparities in these outcomes remain.

2-6. Infant mortality rates in the United States vary across and within states, with 18 states having rates higher than the national average. Access to prenatal and neonatal intensive care, as well as early interventional programs, also varies across states.

2-7. Mortality and severity of morbidity among infants born preterm are inversely proportional to gestational age, although all preterm and LBW neonates have increased rates of short- and long-term morbidity.

2-8. In the past two decades, advances in neonatal care, such as routine use of antenatal steroids and reduced use of postnatal steroids, increased use of noninvasive respiratory support, and sepsis prevention initiatives, have focused on improving outcomes for infants born preterm while maintaining or improving survival.

2-9. Complementing advances in medical care, hospital-based modifications to environments and specific developmental interventions have been implemented in some neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) to promote optimal neonatal development. Examples of such interventions include the implementation of kangaroo care, minimized handling of extremely LBW infants by medical staff, reduced direct lighting, and increased involvement of parents in the day-to-day care of their infants.

2-10. There is a dearth of statewide and nationwide data measuring long-term functional outcomes for infants born in gestational age groups across the LBW spectrum.

Conclusions

2-1. Current estimates of survival are based on gestational age rather than birth weight.

2-2. Technological and medical advances in neonatal care have improved survivability for infants born at lower gestational ages. However, long-term morbidities (such as cognitive, motor, behavioral, and functional outcomes) remain high.

2-3. The risk of disability or poor health and developmental outcomes decreases as gestational age increases, but the highest-risk category remains infants who are born extremely preterm.

2-4. Infants born small for gestational age (i.e., at or below the 10th percentile for gestational age) are at increased risk of having developmental delays associated with poor growth of the brain and body.

2-5. Differences in state and local resources for access to prenatal, perinatal, and neonatal care, as well as differences in access to services such as Early Intervention and NICU follow-up programs, likely contribute to the differences across states in infant mortality rates and medical as well as developmental outcomes.

2-6. Interventions to decrease the adverse effects of social determinants of health (e.g., racial and structural inequities), which may also impact access to and engagement with care services, improve health outcomes, including medical and developmental morbidities.

2-7. Greater collection and availability of data on long-term functional outcomes for infants born at lower gestational ages may inform interventions and mitigate adverse health effects.

REFERENCES

AACPDM (American Academy for Cerebral Palsy and Developmental Medicine). 2023. Early detection of cerebral palsy. https://www.aacpdm.org/publications/care-pathways/early-detection-of-cerebral-palsy (accessed July 24, 2023).

AAP (American Academy of Pediatrics). 2008. Hospital discharge of the high-risk neonate, from the committee on fetus and newborn. Pediatrics 122(5):1119–1126.

ACOG (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists). 2017. Committee opinion no 700: Methods for estimating the due date. Obstetrics and Gynecology 129(5):e150–e154.

ACOG. 2018a. ACOG committee opinion no. 736: Optimizing postpartum care. Obstetrics and Gynecology 131(5):e140–e150.

ACOG. 2018b. ACOG committee opinion no. 741: Maternal immunization. Obstetrics and Gynecology 131(6):e214–e217.

Almeida, J., L. Bécares, K. Erbetta, V. R. Bettegowda, and I. B. Ahluwalia. 2018. Racial/ethnic inequities in low birth weight and preterm birth: The role of multiple forms of stress. Maternal and Child Health Journal 22(8):1154–1163.

Aubin, A. M., L. McAuliffe, K. Williams, A. Issah, R. Diacci, J. E. McAuliffe, S. Sabdia, J. Phung, C. A. Wang, and C. E. Pennell. 2023. Combined vaginal progesterone and cervical cerclage in the prevention of preterm birth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology Maternal-Fetal Medicine 5(8):101024.

Ballard, J. L., J. C. Khoury, K. Wedig, L. Wang, B. L. Eilers-Walsman, and R. Lipp. 1991. New Ballard score, expanded to include extremely premature infants. Journal of Pediatrics 119(3):417–423.

Banerji, A. I., A. Hopper, M. Kadri, B. Harding, and R. Phillips. 2022. Creating a small baby program: A single center’s experience. Journal of Perinatology 42(2):277–280.

Basilio, E., R. Chen, A. C. Fernandez, A. M. Padula, J. F. Robinson, and S. L. Gaw. 2022. Wildfire smoke exposure during pregnancy: A review of potential mechanisms of placental toxicity, impact on obstetric outcomes, and strategies to reduce exposure. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19(21).

Bekkar, B., S. Pacheco, R. Basu, and N. DeNicola. 2020. Association of air pollution and heat exposure with preterm birth, low birth weight, and stillbirth in the US: A systematic review. JAMA Network Open 3(6):e208243.

Bell, E. F., S. R. Hintz, N. I. Hansen, C. M. Bann, M. H. Wyckoff, S. B. Demauro, M. C. Walsh, B. R. Vohr, B. J. Stoll, W. A. Carlo, K. P. Van Meurs, M. A. Rysavy, R. M. Patel, S. L. Merhar, P. J. Sánchez, A. R. Laptook, A. M. Hibbs, C. M. Cotten, C. T. D’Angio, S. Winter, J. Fuller, A. Das; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network. 2022. Mortality, in-hospital morbidity, care practices, and 2-year outcomes for extremely preterm infants in the US, 2013–2018. JAMA 327(3):248–263.

Bhutta, A. T., M. A. Cleves, P. H. Casey, M. M. Cradock, and K. J. S. Anand. 2002. Cognitive and behavioral outcomes of school-aged children who were born preterm. JAMA 288(6):728.

Borrell, L. N., J. R. Elhawary, E. Fuentes-Afflick, J. Witonsky, N. Bhakta, A. H. Wu, K. BibbinsDomingo, J. R. Rodríguez-Santana, M. A. Lenoir, and J. R. Gavin III. 2021. Race and genetic ancestry in medicine—A time for reckoning with racism. New England Journal of Medicine 384(5):474–480.

Boss, R. D., J. C. Raisanen, K. Detwiler, et al. 2020. Lived experience of pediatric home health care among families of children with medical complexity. Clinical Pediatrics 59(2):178-187.

Boyd, R. W., E. G. Lindo, L. D. Weeks, and M. R. McLemore. 2020. On racism: A new standard for publishing on racial health inequities. Health Affairs Forefront. https://doi.org/10.1377/forefront.20200630.939347.

Brown, C. C., J. E. Moore, H. C. Felix, M. K. Stewart, and J. M. Tilford. 2020. Geographic hotspots for low birthweight: An analysis of counties with persistently high rates. INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing 57:e0046958020950999.

Bryant, A. S., A. Worjoloh, A. B. Caughey, and A. E. Washington. 2010. Racial/ethnic disparities in obstetric outcomes and care: Prevalence and determinants. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 202(4):335–343.

Busque, A. A., E. Jabbour, S. Patel, É. Couture, J. Garfinkle, M. Khairy, M. Claveau, and M. Beltempo. 2022. Incidence and risk factors for autism spectrum disorder among infants born <29 weeks’ gestation. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health 27(6):346–352.

Cannavò, L., I. Rulli, R. Falsaperla, G. Corsello, and E. Gitto. 2020. Ventilation, oxidative stress and risk of brain injury in preterm newborn. Italian Journal of Pediatrics 46(1):100.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2011. User guide to the 2011 period linked birth/infant death public file. https://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/health_statistics/NCHS/Dataset_Documentation/DVS/periodlinked/LinkPE11Guide.pdf.

CDC. 2012. User guide to the 2012 period linked birth/infant death public file. https://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/health_statistics/NCHS/Dataset_Documentation/DVS/periodlinked/LinkPE12Guide.pdf.

CDC. 2014. User guide to the 2014 period linked birth/infant death public use file. https://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/health_statistics/nchs/dataset_documentation/DVS/periodlinked/LinkPE14Guide.pdf.

CDC. 2015. User guide to the 2015 period linked birth/infant death public use file. https://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/Dataset_Documentation/DVS/periodlinked/LinkPE15Guide.pdf.

CDC. 2016. User guide to the 2016 period linked birth/infant death public use file. https://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/Dataset_Documentation/DVS/periodlinked/LinkPE16Guide.pdf.

Cheong, J. L. Y., J. E. Olsen, K. J. Lee, A. J. Spittle, G. F. Opie, M. Clark, R. A. Boland, G. Roberts, E. K. Josev, N. Davis, L. M. Hickey, P. J. Anderson, L. W. Doyle, and the Victorian Infant Collaborative Study Group. 2021. Temporal trends in neurodevelopmental outcomes to 2 years after extremely preterm birth. JAMA Pediatrics 175(10): 1035–1042.

Chyn, E., S. Gold, and J. Hastings. 2021. The returns to early-life interventions for very low birth weight children. Journal of Health Economics 75:102400.

Clifford, V., S. M. Garland, and K. Grimwood. 2012. Prevention of neonatal group B streptococcus disease in the 21st century. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health 48(9):808–815.

Costello, J. M., and S. M. Bradley. 2021. Low birth weight and congenital heart disease: Current status and future directions. The Journal of Pediatrics 238(November):9–10.

Costeloe, K., and EPICure Study Group. 2006. EPICure: facts and figures: Why preterm labour should be treated. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology 113:10–12.

Davidson, K. W., M. J. Barry, C. M. Mangione, M. Cabana, A. B. Caughey, E. M. Davis, K. E. Donahue, C. A. Doubeni, M. Kubik, L. Li, G. Ogedegbe, L. Pbert, M. Silverstein, M. A. Simon, J. Stevermer, C. W. Tseng, and J. B. Wong. 2021. Aspirin use to prevent preeclampsia and related morbidity and mortality: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA 326(12):1186–1191.

de Jong, M., M. Verhoeven, and A. L. van Baar. 2012. School outcome, cognitive functioning, and behaviour problems in moderate and late preterm children and adults: A review. Seminars in Fetal and Neonatal Medicine 17(3):163–169.

Donovan, E. F., J. E. Tyson, R. A. Ehrenkranz, J. Verter, L. L. Wright, S. B. Korones, C. R. Bauer, S. Shankaran, B. J. Stoll, A. A. Fanaroff, W. Oh, J. A. Lemons, D. K. Stevenson, and L. A. Papile. 1999. Inaccuracy of Ballard scores before 28 weeks’ gestation. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network. Journal of Pediatrics 135(2 Pt 1):147–152.

Dubowitz, L. M., V. Dubowitz, and C. Goldberg. 1970. Clinical assessment of gestational age in the newborn infant. The Journal of Pediatriacs 77(1):1–10.

Dzekem, B. S., B. Aschebrook-Kilfoy, and C. O. Olopade. 2023. Air pollution and racial disparities in pregnancy outcomes in the United States: A systematic review. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. Online ahead of print. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-023-01539-z.

EGA Institute for Women’s Health. n.d. EPICure. https://www.ucl.ac.uk/womens-health/research/neonatology/epicure (accessed October 4, 2023).

Ely, D. M. and A. K. Driscoll. 2019. Infant mortality in the United States, 2017: Data from the period linked birth/infant death file. National Vital Statistics Reports 68(10):1–20.

Ely, D. M. and A. K. Driscoll. 2020. Infant mortality in the United States, 2018: Data from the period linked birth/infant death file. National Vital Statistics Reports 69(7):1–18.

Ely, D. M. and A. K. Driscoll. 2021. Infant mortality in the United States, 2019: Data from the period linked birth/infant death file. National Vital Statistics Reports 70(5):1–18.

Ely, D. M., and A. K. Driscoll. 2022. Infant mortality in the United States, 2020: Data from the period linked birth/infant death file. National Vital Statistics Reports 71(5):1–18.

Ely, D. M., and A. K. Driscoll. 2023. Infant mortality in the United States, 2021: Data from the period linked birth/infant death file. National Vital Statistics Reports 72(11):1–19.

Everitt, I. K., P. M. Freaney, M. C. Wang, W. A. Grobman, M. J. O’Brien, L. R. Pool, and S. S. Khan. 2022. Association of state Medicaid expansion status with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy in a singleton first live birth. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes 15(1):e008249.

Fathi, O., L. D. Nelin, E. G. Shepherd, and K. M. Reber. 2022. Development of a small baby unit to improve outcomes for the extremely premature infant. Journal of Perinatology 42(2):157–164.

Friedman-Krauss, A. H., and W. S. Barnett. 2023. The state(s) of early intervention and early childhood special education: Looking at equity. National Institute for Early Education Research. https://nieer.org/policy-landscapes/special-education-report (accessed January 25, 2024).

Goldstein, R. F., S. K. Abell, S. Ranasinha, M. Misso, J. A. Boyle, M. H. Black, N. Li, G. Hu, F. Corrado, L. Rode, Y. J. Kim, M. Haugen, W. O. Song, M. H. Kim, A. Bogaerts, R. Devlieger, J. H. Chung, and H. J. Teede. 2017. Association of gestational weight gain with maternal and infant outcomes. JAMA 317(21):2207.

Gruber, K. J., S. H. Cupito, and C. F. Dobson. 2013. Impact of doulas on healthy birth outcomes. Journal of Perinatal Education 22(1):49–58.

Guth, M. and K. Diep 2023. What does the recent literature say about Medicaid expansion?: Impacts on sexual and reproductive health. KFF. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/what-does-the-recent-literature-say-about-medicaid-expansion-impacts-on-sexual-and-reproductive-health/ (accessed January 25, 2024).

Gyamfi-Bannerman, C., E. A. Thom, S. C. Blackwell, A. T. N. Tita, U. M. Reddy, G. R. Saade, D. J. Rouse, D. S. McKenna, E. A. S. Clark, J. M. Thorp, E. K. Chien, A. M. Peaceman, R. S. Gibbs, G. K. Swamy, M. E. Norton, B. M. Casey, S. N. Caritis, J. E. Tolosa, Y. Sorokin, J. P. Vandorsten, and L. Jain. 2016. Antenatal betamethasone for women at risk for late preterm delivery. New England Journal of Medicine 374(14):1311–1320.

Hamilton, B. E., J. A. Martin, and M. J. K. Osterman. 2023. Births: Provisional data for 2022. National Vital Statistics Reports, Report no. 28. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/vsrr/vsrr028.pdf (accessed August 4, 2023).

Henderson, J. T., K. K. Vesco, C. A. Senger, R. G. Thomas, and N. Redmond. 2021. Aspirin use to prevent preeclampsia and related morbidity and mortality: Updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA 326(12):1192–1206.

Hill, L., S. Artiga, and U. Ranji. 2022. Racial disparities in maternal and infant health: Current status and efforts to address them. KFF. https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/issue-brief/racial-disparities-in-maternal-and-infant-health-current-status-and-efforts-to-address-them (accessed January 25, 2024).

Hirai, A. H., M. D. Kogan, V. Kandasamy, C. Reuland, and C. Bethell. 2018. Prevalence and variation of developmental screening and surveillance in early childhood. JAMA Pediatrics 172(9):857.

Hollenbach, S. J., L. L. Thornburg, J. C. Glantz, and E. Hill. 2021. Associations between historically redlined districts and racial disparities in current obstetric outcomes. JAMA Network Open 4(9):e2126707.

Jang, C. J., and H. C. Lee. 2022. A review of racial disparities in infant mortality in the US. Children (Basel) 9(2):257.

Kang, H. G., E. Y. Choi, H. Cho, M. Kim, C. S. Lee, and S. M. Lee. 2022. Oxygen care and treatment of retinopathy of prematurity in ocular and neurological prognosis. Scientific Reports 12(1):341.

Kennedy-Moulton, K., S. Miller, P. Persson, M. Rossin-Slater, L. Wherry, and G. Aldana. 2022. Maternal and infant health inequality: New evidence from linked administrative data. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 30693. https://doi.org/10.3386/w30693.

Komro, K. A., M. D. Livingston, S. Markowitz, and A. C. Wagenaar. 2016. The effect of an increased minimum wage on infant mortality and birth weight. American Journal of Public Health 106(8):1514–1516.

Komro, K. A., S. Markowitz, M. D. Lingston, and A. C. Wagenaar. 2019. Effects of state-level Earned Income Tax Credit laws on birth outcomes by race and ethnicity. Health Equity 3(1):61–67.

Khasawneh, W., and W. Khriesat. 2020. Assessment and comparison of mortality and short-term outcomes among premature infants before and after 32-week gestation: A cross-sectional analysis. Annals of Medicine and Surgery 60:44–49.

Khurana, S., A. E. Kane, S. E. Brown, T. Tarver, and S. C. Dusing. 2020. Effect of neonatal therapy on the motor, cognitive, and behavioral development of infants born preterm: A systematic review. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology 62(6):684–692.

Lin, Y. W., S. N. Chen, C. H. Muo, F. C. Sung, and M. H. Lin. 2022. Risk of retinopathy of prematurity in preterm births with respiratory distress syndrome: A population-based cohort study in Taiwan. International Journal of General Medicine 15:2149–2162.

Lisanti, A. J., K. C. Uzark, T. M. Harrison, J. K. Peterson, S. C. Butler, T. A. Miller, K. Y. Allen, S. P. Miller, C. E. Jones, the American Heart Association Pediatric Cardiovascular Nursing Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular Stroke Nursing Council on Lifelong Congenital Heart Disease and Heart Health in the Young, and the Council on Hypertension. 2023. Developmental care for hospitalized infants with complex congenital heart disease: A science advisory from the American Heart Association. Journal of the American Heart Association 12(3):e028489.

Lubker Cornish, D., and S. Roberts Dobie. 2018. Social support in the “fourth trimester”: A qualitative analysis of women at 1 month and 3 months postpartum. Journal of Perinatal Education 27(4):233–242.

Ma, Q., H. Wang, E. T. Rolls, S. Xiang, J. Li, Y. Li, Q. Zhou, W. Cheng, and F. Li. 2022. Lower gestational age is associated with lower cortical volume and cognitive and educational performance in adolescence. BMC Medicine 20(1).

March of Dimes. 2023. Maternity care deserts report. https://www.marchofdimes.org/maternity-care-deserts-report (accessed September 29, 2023).

Martin, J. A., B. E. Hamilton, P. D. Sutton, S. J. Ventura, T. J. Mathews, S. Kirmeyer, and M. J. K. Osterman. 2010. Births: Final data for 2007. National Vital Statistics Reports 58(24). https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr58/nvsr58_24.pdf (accessed August 4, 2023).

Mathews, T. J. and M. F. MacDorman. 2006. Infant mortality statistics from the 2003 period linked birth/infant death data set National Vital Statistics Reports 54(16):1–30.

Mathews, T. J. and M. F. MacDorman. 2007. Infant mortality statistics from the 2004 period linked birth/infant death data set. National Vital Statistics Reports 55(14):1–32.

Mathews, T. J. and M. F. MacDorman. 2008. Infant mortality statistics from the 2005 period linked birth/infant death data set. National Vital Statistics Reports 57(2):1–32.

Mathews, T. J. and M. F. MacDorman. 2010. Infant mortality statistics from the 2006 period linked birth/infant death data set. National Vital Statistics Reports 58(17):1–32.

Mathews, T. J. and M. F. MacDorman. 2011. Infant mortality statistics from the 2007 period linked birth/infant death data set. National Vital Statistics Reports 59(6):1–31.

Mathews, T. J. and M. F. MacDorman. 2012. Infant mortality statistics from the 2008 period linked birth/infant death data set. National Vital Statistics Reports 60(5):1–28.

Mathews, T. J. and M. F. MacDorman. 2013a. Infant mortality statistics from the 2009 period linked birth/infant death data set. National Vital Statistics Reports 61(8):1–28.

Mathews, T. J. and M. F. MacDorman. 2013b. Infant mortality statistics from the 2010 period linked birth/infant death data set. National Vital Statistics Reports 62(8):1–27.

Mathews, T. J., F. Menacker, and M. F. MacDorman. 2002. Infant mortality statistics from the 2000 period linked birth/infant death data set. National Vital Statistics Reports 50(12):1–28.

Mathews, T. J., F. Menacker, and M. F. MacDorman. 2003. Infant mortality statistics from the 2001 period linked birth/infant death data set. National Vital Statistics Reports 52(2):1–27.

Mathews, T. J., M. F. MacDorman, and M. E. Thoma. 2004. Infant mortality statistics from the 2002 period linked birth/infant death data set. National Vital Statistics Reports 53(10):1–30.

Mathews, T. J., M. F. MacDorman, and M. E. Thoma. 2015. Infant mortality statistics from the 2013 period linked birth/infant death data set. National Vital Statistics Reports 64(9):1–30.

Mayo Clinic. n.d. Congenital heart defects in children. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseasesconditions/congenital-heart-defects-children/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20350080 (accessed January 25, 2024).

Montoya-Williams, D., M. Passarella, and S. A. Lorch. 2020. The impact of paid family leave in the United States on birth outcomes and mortality in the first year of life. Health Services Research 55 (Suppl 2):807–814.

Murphy, S. L., K. D. Kochanek, J. Xu, and E. Arias. 2021. Mortality in the United States, 2020. NCHS Data Brief (427):1–8.

Murray, M. J., and J. Richardson. 2017. Neonatology. In Core concepts of pediatrics, 2nd edition. Galveston, TX: University of Texas Medical Branch.

Myrhaug, H. T., K. G. Brurberg, L. Hov, K. Håvelsrud, and L. M. Reinar. 2017. NIPH systematic reviews: Executive summaries. In Prognosis and follow-up of extreme preterm infants: A systematic review. Oslo, Norway: Knowledge Centre for the Health Services at the Norwegian Institute of Public Health (NIPH).

Naidu, K., and K. L. Fredlund. 2023. Gestational age assessment. In StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526000.

Nguyen, T. M., C. A. Crowther, D. Wilkinson, and E. Bain. 2013. Magnesium sulphate for women at term for neuroprotection of the fetus. Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews (2):Cd009395.

NRN (Neonatal Research Network). n.d. Research to improve the health of low birth weight and premature infants. https://neonatal.rti.org (accessed September 25, 2023)

Orchinik, L. J., H. G. Taylor, K. A. Espy, N. Minich, N. Klein, T. Sheffield, and M. Hack. 2011. Cognitive outcomes for extremely preterm/extremely low birth weight children in kindergarten. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society 17(6):1067–1079.

Osterman, M. J. K., B. E. Hamilton, J. A. Martin, A. K. Driscoll, and C. P. Valenzuela. 2023. Births: Final data for 2021. National Vital Statistics Reports 72(1). Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. https://dx.doi.org/10.15620/cdc:122047.

Patel, R. M. 2016. Short- and long-term outcomes for extremely preterm infants. American Journal of Perinatology 33(3):318–328. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0035-1571202.

Pavel, A. M., J. M. Rennie, L. S. de Vries, M. Blennow, A. Foran, D. K. Shah, R. M. Pressler, O. Kapellou, E. M. Dempsey, S. R. Mathieson, E. Pavlidis, L. C. Weeke, V. Livingstone, D. M. Murray, W. P. Marnane, and G. B. Boylan. 2022. Neonatal seizure management: Is the timing of treatment critical? Journal of Pediatrics 243:61–68.e2.

Payne, N. R., M. J. Finkelstein, M. Liu, J. W. Kaempf, P. J. Sharek, and S. Olsen. 2010. NICU practices and outcomes associated with 9 years of quality improvement collaboratives. Pediatrics 125(3):437–446.

Pierrat, V., L. Marchand-Martin, S. Marret, C. Arnaud, V. Benhammou, G. Cambonie, T. Debillon, M.-N. Dufourg, C. Gire, F. Goffinet, M. Kaminski, A. Lapillonne, A.-S. Morgan, J. Rozé, S. Twilhaar, M.-A. Charles, P. Ancel, and EPIPAGE-2 writing group. 2021. Neurodevelopmental outcomes at age 5 among children born preterm: EPIPAGE-2 cohort study. BMJ 373:n741.

Pineda, R., K. Knudsen, C. C. Breault, E. E. Rogers, W. J. Mack, and A. Fernandez-Fernandez. 2023. NICUs in the US: Levels of acuity, number of beds, and relationships to population factors. Journal of Perinatology 43(6):796–805.

Radley, D. C., J. C. Baumgartner, S. R. Collins, and L. C. Zephyrin. 2023. 2023 scorecard on state health system performance. The Commonwealth Fund. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/scorecard/2023/jun/2023-scorecard-state-health-system-performance (accessed September 28, 2023).

Republique Francaise. n.d. EPIPAGE 2. https://francecohortes.org/en/cohorts-project/epipage-2 (accessed September 28, 2023).

Ro, A., R. E. Goldberg, and J. B. Kane. 2019. Racial and ethnic patterning of low birth weight, normal birth weight, and macrosomia. Preventive Medicine 118:196–204.

Rouse, D. J., D. G. Hirtz, E. Thom, M. W. Varner, C. Y. Spong, B. M. Mercer, J. D. Iams, R. J. Wapner, Y. Sorokin, J. M. Alexander, M. Harper, J. M. Thorp, S. M. Ramin, F. D. Malone, M. Carpenter, M. Miodovnik, A. Moawad, M. J. O’Sullivan, A. M. Peaceman, G. D. V. Hankins, O. Langer, S. N. Caritis, and J. M. Roberts. 2008. A randomized, controlled trial of magnesium sulfate for the prevention of cerebral palsy. New England Journal of Medicine 359(9):895–905.

Sacchi, C., C. Marino, C. Nosarti, A. Vieno, S. Visentin, and A. Simonelli. 2020. Association of intrauterine growth restriction and small for gestational age status with childhood cognitive outcomes. JAMA Pediatrics 174(8):772.

Saigal, S., and L. W. Doyle. 2008. An overview of mortality and sequelae of preterm birth from infancy to adulthood. Lancet 371(9608):261–269.

Sanlorenzo, L. A., and L. D. Hatch. 2023. Developing a respiratory quality improvement program to prevent and treat bronchopulmonary dysplasia in the neonatal intensive care unit. Clinics in Perinatology 50(2):363–380.

Savage, J. S. 2020. A fourth trimester action plan for wellness. The Journal of Perinatal Education 29(2):103–112.

Schulzke, S. M., and B. Stoecklin. 2022. Update on ventilatory management of extremely preterm infants: A neonatal intensive care unit perspective. Pediatric Anesthesia 32(2):363–371.

Séassau, A., P. Munos, C. Gire, B. Tosello, and I. Carchon. 2023. Neonatal care unit interventions on preterm development. Children (Basel) 10(6):999.

Sharma, D., P. Sharma, and S. Shastri. 2017. Genetic, metabolic and endocrine aspect of intrauterine growth restriction: An update. Journal of Maternal-Fetal and Netonatal Medicine 30(19):2263–2275.

Shennan, A., N. Suff, and B. Jacobsson. 2021. FIGO good practice recommendations on magnesium sulfate administration for preterm fetal neuroprotection. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics 155(1):31–33.

Shepherd, E., A. M. Knupp, S. E. Welty, K. M. Susey, W. P. Gardner, and A. L. Gest. 2012. An interdisciplinary bronchopulmonary dysplasia program is associated with improved neurodevelopmental outcomes and fewer rehospitalizations. Journal of Perinatology 32(1):33–38.

Skoff, T. H., L. Deng, C. H. Bozio, and S. Hariri. 2023. US infant pertussis incidence trends before and after implementation of the maternal tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis vaccine. JAMA Pediatrics 177(4):395–400.

Smith, V. C. 2022. NICU discharge preparation and transition planning: Introduction. Journal of Perinatology 42(Suppl 1):5–6.

Stark, A. R., D. Pursley, L.-A. Papile, E. C. Echenwalk, C. T. Hankins, R. K. Buck, T. J. Wallace, P. G. Bondurant, and N. E. Faster. 2023. Standards for levels of neonatal Care: II, III, and IV. Pediatrics 151(6):e2023061957.

Straughen, J. K., J. Clement, L. Schulz, G. Alexander, Y. Hill-Ashford, and K. Wisdom. 2023. Community health workers as change agents in improving equity in birth outcomes in Detroit. PLoS One 18(2):e0281450.

SUPPORT Study Group of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD Neonatal Research Network 2010. Target ranges of oxygen saturation in extremely preterm infants. New England Journal of Medicine 362(21):1959–1969.

Talavera M. M., G. Bixler, C. Cozzi, J. Dail, R. R. Miller, R. McClead Jr., and K. Reber. 2016. Quality improvement initiative to reduce the necrotizing enterocolitis rate in premature infants. Pediatrics 137(5):e20151119. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-1119.

Tita, A. T., J. M. Szychowski, K. Boggess, L. Dugoff, B. Sibai, K. Lawrence, B. L. Hughes, J. Bell, K. Aagaard, R. K. Edwards, K. Gibson, D. M. Haas, L. Plante, T. Metz, B. Casey, S. Esplin, S. Longo, M. Hoffman, G. R. Saade, K. K. Hoppe, J. Foroutan, M. Tuuli, M. Y. Owens, H. N. Simhan, H. Frey, T. Rosen, A. Palatnik, S. Baker, P. August, U. M. Reddy, W. Kinzler, E. Su, I. Krishna, N. Nguyen, M. E. Norton, D. Skupski, Y. Y. El-Sayed, D. Ogunyemi, Z. S. Galis, L. Harper, N. Ambalavanan, N. L. Geller, S. Oparil, G. R. Cutter, and W. W. Andrews. 2022. Treatment for mild chronic hypertension during pregnancy. New England Journal of Medicine 386(19):1781–1792.

Villar, J., A. T. Papageorghiou, H. E. Knight, M. G. Gravett, J. Iams, S. A. Waller, M. Kramer, J. F. Culhane, F. C. Barros, A. Conde-Agudelo, Z. A. Bhutta, and R. L. Goldenberg. 2012. The preterm birth syndrome: A prototype phenotypic classification. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 206(2):119–123.

Vincer, M. J., A. C. Allen, K. S. Joseph, D. A. Stinson, H. Scott, and E. Wood. 2006. Increasing prevalence of cerebral palsy among very preterm infants: A population-based study. Pediatrics 118(6):e1621–e1626.

Vesoulis, Z. A., and A. M. Mathur. 2014. Advances in management of neonatal seizures. Indian Journal of Pediatrics 81(6):592–598. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12098-014-1457-9.

Walters, A., C. McKinlay, P. Middleton, J. E. Harding, and C. A. Crowther. 2022. Repeat doses of prenatal corticosteroids for women at risk of preterm birth for improving neonatal health outcomes. Cochrane Database Systematic Review 4(4):Cd003935.

Wapner, R. J., C. Gyamfir-Bannerman, E. A. Thom, and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver Naitonal Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. 2016. What we have learned about antenatal corticosteroid regimens. Seminars in Perinatology 40(5):291–297.

Wehby, G. L., D. Dave, and R. Kaestner. 2020. Effects of the minimum wage on infant health. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 39(2):411–443.

WHO (World Health Organization). 2015. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems, 10th revision. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

WHO. 2023. Preterm birth. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/preterm-birth (accessed July 1, 2023).

Wilson, A., V. A. Hodgetts-Morton, E. J. Marson, A. D. Markland, E. Larkai, A. Papadopoulou, A. Coomarasamy, A. Tobias, D. Chou, O. T. Oladapo, M. J. Price, K. Morris, and I. D. Gallos. 2022. Tocolytics for delaying preterm birth: A network meta-analysis (0924). Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews 8(8):Cd014978.

Wilson-Costello, D., H. Friedman, N. Minch, B. Siner, G. Taylor, M. Schluchter, and M. Hack. 2007. Improved neurodevelopmental outcomes for extremely low birth weight infants in 2000–2002. Pediatrics 119(1):37–45.

Younge, N., P. B. Smith, K. E. Gustafson, W. Malcolm, P. Ashley, C. M. Cotton, R. N. Goldberg, and R. F. Goldstein. 2016. Improved survival and neurodevelopmental outcomes among extremely premature infants born near the limit of viability. Early Human Development 95:5–8.

Younge, N., R. F. Goldstein, C. M. Bann, S. R. Hintz, R. M. Patel, P. B. Smith, E. F. Bell, M. A. Rysavy, A. F. Duncan, B. R. Vohr, A. Das, R. N. Goldberg, R. D. Higgins, and C. M. Cotten. 2017. Survival and neurodevelopmental outcomes among periviable infants. New England Journal of Medicine 376(7):617–628.

Zaretsky, M. V., S. Tong, M. Lagueux, F. Y. Lim, N. Khalek, S. P. Emery, S. Davis, A. J. Moon-Grady, K. Drennan, M. C. Treadwell, E. Petersen, P. Santiago-Munoz, and R. Brown. 2019. North American Fetal Therapy Network: Timing of and indications for delivery following laser ablation for twin-twin transfusion syndrome. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology Maternal-Fetal Medicine 1(1):74–81.

This page intentionally left blank.