Low Birth Weight Babies and Disability (2024)

Chapter: 3 Developmental Domains and Trajectories

3

Developmental Domains and Trajectories

Children typically develop a wide range of skills across multiple domains beginning at birth and continuing into early adulthood. Anything that interferes with an environment conducive to typical development can negatively affect a child’s development, potentially resulting in delayed development or ongoing health conditions. Low birth weight (LBW) infants who are born preterm or small for gestational age are at increased risk for health conditions or impairments that can impede their skill development and negatively affect their ability to function.

This chapter explains the relationship between developmental skills and function and provides a crosswalk for the terminology used by each of four conceptual frameworks concerned with development and function in children. The committee was tasked with describing “the progression of the development for [LBW] babies and the age ranges normally looked at for this development” and “the age range in which differences in health and development exist between [LBW] babies and babies born at normal weights.” To address these tasks, the chapter gives an overview of typical developmental progress and describes altered developmental trajectories that may be seen in children who are born LBW. The chapter also reviews “clinical standards for calculating and considering the ‘corrected chronological age’ when evaluating possible developmental delays in children who were born prematurely.” A discussion of when developmental delays become disorders is provided to address the question of “points in time where it can be determined if an issue will be permanent or can improve,” as well as “variability in the period of time a child’s functioning can be expected to improve.”

DEVELOPMENTAL SKILLS AND FUNCTION

Development, indicated by attainment of milestones, is the framework for understanding infancy and early childhood. Developmental skills provide the scaffolding for function. For example, acquisition of large-muscle control and coordination enables sitting, standing, crawling, and ambulation (i.e., mobility); gaining the ability to control hand and finger movements enables independent feeding; and mastery of combining speech sounds into words enables communication. Development is a progressive process (e.g., sitting to standing to walking) that can be interrupted by impairments that can act as barriers to the development of later skills. In the literature and in infant and child assessments, developmental skills typically are grouped into developmental domains, while functional skills are grouped into functional domains, as described in the following section. Although there are similarities in terminology among some of the developmental and functional domains, there seldom is a one-to-one correspondence.

In addition, some skills can be considered in two different ways: as developmental milestones and as indicators of functioning. To illustrate, if the skill of drinking from a cup when held does not develop within the timeframe during which that skill is typically expected to be seen, this observation may be described as a delay in the child’s development. However, the absence of this skill has meaning in and of itself because drinking from a cup is a functional skill needed for participating in daily life. Thus within a developmental assessment, drinking from a cup is used as an indicator of whether overall development is progressing as expected, whereas within a functional assessment, it is treated as an indicator of the child’s progression in acquiring skills for daily living. Different sets of measures are used to assess developmental skills and function. Although the content of some items may be similar across the two types of measures, the interpretation of findings is different.

THE PROGRESSION OF DEVELOPMENT

Children’s development and function are inextricably bound not only to their health but also to their social milieu or environment, the latter providing opportunities and supports necessary for their progression in both domains. Children are expected to be dependent on the family and to evolve to independence gradually through their interactions with family and community. The critical relationship between child and family is reflected in the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) framework presented in Chapter 1. Delays in development and impairments (i.e., problems with body structures and functions) in children that affect the acquisition of functional skills, as well as children’s

environments and the opportunities and barriers to which they are exposed, can adversely affect the transition from typical childhood dependence to adult independence.

Development refers to an active process that depends on the interaction between the development of various physiological and organ systems and experiences and the environment in the context of genetic and epigenetic factors. Thus the foundation of development and the acquisition of developmental and functional skills lies in the active interplay between physiological and anatomical maturation and experience. Neurodevelopment depends on the formation of neural networks in the nervous system, which in turn depends on developing children’s physical and psychosocial environments, beginning in utero and continuing into their home environment with their primary caregivers and other family members. Such factors as parenting and parenting skills affect development, and the availability of appropriate learning opportunities and supports in the environment is crucial. Anything that interferes with an environment conducive to maximal development can negatively affect a child’s development, potentially resulting in delayed development or ongoing health conditions.

Development in LBW infants may be affected by related medical conditions (Chapter 4) and social exposures in their postbirth environment. Preterm infants often require intensive and/or extended hospitalization compared with their term counterparts. This is particularly true for LBW infants who are eligible for Supplemental Security Income (SSI) benefits based on the listings criteria for LBW. Although physiology is stabilized in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) and specialized treatments enable medical progress/survival, an infant’s ability to participate in the family unit is significantly limited. Developmental and growth trajectories are often impeded in the first weeks to months of life in the NICU (Cheong et al., 2020; Subedi et al., 2017). These infants need highly specialized coordination of care by their families and continuous adjustment to their circumstances.

Children and adults differ in important ways with respect to the effects of impairments on functioning. When a child has a health condition or an impairment that impedes development, the essential foundation for the acquisition of functional skills is affected. In contrast, when adults lose function in a certain area, they have lost a skill that was previously developed. Thus during rehabilitation, adults have prior experience with a skill they want to regain, whereas children lack that experience.

Applying a life-course perspective, practitioners attempt to provide support, management, and treatment for children and families that can lead to the greatest adult potential (see Chapter 1). Early diagnostic and developmental assessment facilitates initiation of interventions, including family-centered care and family-integrated care, which can improve family and

infant functioning both in the NICU and in the first years of life (Davidson et al., 2017; Franck et al., 2020).

DEVELOPMENTAL AND FUNCTIONAL DOMAINS

In determining children’s eligibility for SSI, the Social Security Administration (SSA) considers evidence of significant limitations in one or more of six domains of functioning. This evidence is obtained from assessments conducted by professionals and service agencies, which frequently describe children’s development using terminology and conceptual frameworks that differ from SSA’s, as well as from each other. To avoid confusion when describing the literature on LBW babies, this section provides a brief overview of each of four frameworks and the links among as well as the differences in their terminology: the developmental milestones of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP)/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), which specify primarily developmental domains, and SSA’s framework and the World Health Organization’s ICF, which specify functional domains.

American Academy of Pediatrics/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Developmental Milestones

Early child development has been described in terms of specific skills since the early 20th century, rooted in the landmark “maturational-developmental theory” of Arnold Gesell. In his Developmental Schedules (Gesell, 1925), Gesell divided development into motor, language, adaptive, and personal-social domains. The names and descriptions of these domains have been modified over the past century by different scales and measures, but the categories continue to be based on Gesell’s original work.

Currently, health care providers use milestones in developmental surveillance and screening, especially during well-child visits, to identify children with delays or other atypical development. Developmental surveillance is defined as

a longitudinal process that involves eliciting concerns, taking a developmental history based on milestone attainment, observing milestones and other behaviors, examining the child, and applying clinical judgment during health supervision visits (HSVs). Developmental screening involves the use of validated screening tools at specific ages or when surveillance reveals a concern (Lipkin and Macias, 2020). (Zubler et al., 2022, p. 1)

At present, the most widely used references for developmental milestones in the United States include those published by the AAP in its Bright Futures

manual (Hagan et al., 2017) and the CDC in its Learn the Signs. Act Early materials (CDC, 2023b). Recently, the AAP and CDC joined together to revise the milestones for use in developmental surveillance (Zubler et al., 2022), with renamed domains, to provide new evidence-based standards for early identification of developmental disorders through developmental surveillance and screening (Lipkin and Macias, 2020). The AAP/CDC developmental milestones are currently grouped into four domains:

- movement/physical development;

- language/communication;

- cognitive (learning, thinking, problem solving); and

- social/emotional.

The milestones are published in a set of developmental checklists (CDC, 2023a). Among the important changes in this new set is placement of the milestones in the well-child visit age group that corresponds to the age at which greater than 75 percent of children would be expected to achieve them as opposed to the 50th percentile used in prior lists, providing a clearer indicator of when a child is behind peers (Zubler et al., 2022). In addition, the AAP and CDC created sets of milestones corresponding to the recommended 15- and 30-month child health visits, not previously provided. Sequential failure to meet milestones across the four domains at which 75 percent of peers consistently perform is a red flag for developmental delays.

Zubler and colleagues (2022) note that milestones (e.g., play behaviors) often involve skills across several domains, and the decision about the domains in which to place them was guided by where parents would most likely identify them. Milestones serve as markers or indicators of whether a child’s development is progressing as expected. If the child is lagging, this should trigger further screening and evaluation to assess whether and what kind of problem may be present.

Individuals with Disabilities Education Act

IDEA, first enacted in 1975, ensures a free and appropriate public education for all children, from birth to 21 years of age, who are eligible for special education and related services.1 IDEA is divided into Parts C and B; Part B is discussed in Chapter 5. Part C mandates that all children under the age of 3 be screened and those who meet eligibility requirements be provided with early intervention services that address developmental

___________________

1 Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, 20 U.S.C. § 1400 (2004).

delay. It identifies five domains to be considered when evaluating a child for delayed development or disability:

- physical development (includes vision and hearing),

- communication development,

- cognitive development,

- social or emotional development, and

- adaptive development.2

The five domains are specified in the law but not defined further, although individual states may provide further definition or guidance to be followed for assessment. As listed, the IDEA domains are similar to those defined by the AAP/CDC milestones, with the exception of adaptive development, which is a functional domain.

Social Security Administration’s Framework

SSA identifies its own set of domains that are used for disability determination in children, including the LBW children who are the focus of this report. Under SSA regulations, a child may qualify for SSI in several different ways. First is through documentation of a medical impairment of a level of severity that meets the criteria specified in a particular listing. Children born LBW may automatically qualify for SSI by meeting the criteria in the SSA listing for Low Birth Weight and Failure to Thrive (SSA, 2023). A child may also qualify for SSI if diagnosed with an impairment that functionally equals one of the listings. To functionally equal the listings, an impairment (or combination of impairments) must be of listing-level severity; that is, it must result in “marked” limitations in two domains of functioning or an “extreme” limitation in one domain.3 Domains are broad areas of functioning intended to capture all of what a child can or cannot do. SSA uses the following six domains in its determination:

- moving about and manipulating objects,

- acquiring and using information,

- attending and completing tasks,

- interacting and relating with others,

- caring for [oneself], and

- health and physical well-being.4

___________________

2 Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, 20 U.S.C. § 1432.

3 20 CFR 416.926a(a).

4 20 CFR 416.962a.

SSA’s terminology emphasizes the areas of function that are limited and does not use the terminology of developmental domains.

International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health

Also relevant is the classification system for describing health, functioning, and disability developed by the World Health Organization—the ICF (WHO, 2001) and its related version for children and youth (ICF-CY) (WHO, 2007). The ICF and ICF-CY were created to provide a common framework and language for describing disability across different countries and service systems and are widely used in rehabilitation fields both in the United States and internationally. The ICF framework is the basis for the conceptual framework for this report, as described in Chapter 1.

The ICF framework is intended to capture domains related to health, functioning, and disability rather than domains of development. Its terminology is intended to provide a comprehensive system for describing the impact of a health condition on a person’s functioning at three levels of analysis: body functions and body structures, activity, and participation. In the ICF, body functions (denoted with b codes) are the physiological functions of body systems, including psychological systems. These are the basic abilities required to perform activities (discrete tasks or actions) and to participate (both denoted with d codes) in personally and socially desired settings and roles. From an ICF perspective, when a child is performing a milestone behavior (e.g., using gestures to indicate they want something; taking a few steps), the performance of the behavior indicates capability for activity (d codes). This interpretation is distinguished from inferences about the development or intactness of underlying functions (e.g., for language or mobility) based on observing the behavior, which concern body functions (b codes). The six domains that SSA considers are defined with terms somewhat similar to those of the ICF, as seen in Table 3-1, reflecting the shared emphasis on function of these two frameworks. The exception, health and well-being, would be described in the ICF using codes that reflect the specific areas of health-related concern (b codes).

As discussed, each of the four frameworks described here uses somewhat different terminology to denote domains or aspects of development. Because the frameworks of AAP/CDC and IDEA specify primarily developmental domains, whereas those of SSA and the ICF specify functional domains, a one-to-one correspondence between specific AAP/CDC or IDEA domains and the different functional domains seldom exists. Typically, all developmental domains will impact all functional domains, especially over time. Despite the differences in terminology, however, all of these frameworks are concerned with approximately the same aspects of the child’s development and daily functioning. Table 3-1 provides a simplified

| SSA Domains of Functioning | AAP/CDC Developmental Milestones | IDEA Part C Areas of Development | ICF Chapters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Moving about and manipulating objects | Movement or physical development | Physical | b7: Neuromuscular and movement functions |

| d4: Mobility | |||

| Acquiring and using information | Cognitive | Cognitive | b1: Mental functions |

| d1: Learning and applying knowledge | |||

| Attending and completing tasks | Cognitive | Cognitive | d2: General tasks and demands |

| Interacting and relating with others | Communication | Communication | b3: Voice and speech functions |

| d3: Communication | |||

| Social or emotional | Social or emotional | b122: Global psychosocial functions | |

| d2: Handling stress or managing behavior | |||

| d7: Interpersonal interactions and relationships | |||

| Caring for oneself | Adaptive | Multiple b codes reflect the underlying abilities required for self-care (feeding, toileting, etc.) | |

| d5: Self-care | |||

| Health and physical well-being | Adaptive |

NOTE: AAP/CDC = American Academy of Pediatrics/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; ICF = International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health; IDEA = Individuals with Disabilities Education Act; SSA = U.S. Social Security Administration.

crosswalk showing where and how the terms used in the frameworks most commonly correspond, and a few areas in which a domain may be identified and named in one framework but not another. In the latter case, the content of the “missing” area is likely captured under a different domain.

It is important to note as well that, although the lists of developmental and functional domains imply discrete categories, developmental and functional skills often span multiple domains. Organizing development into domains and lists of milestones is convenient for parental understanding

and identification of foci for intervention, but all developmental skills are interrelated with respect to functioning, and no single domain is sufficient for function.

TYPICAL DEVELOPMENTAL PROGRESS

Assuming a typical developmental trajectory, attainment of skills within the first years of life is rapid and expansive. Skills emerge in various domains at variable rates. Most early developmental measures assess skill attainment within the developmental domains specified in the CDC/AAP milestones—movement or physical development, communication, cognition, and social or emotional development. Table 3-2 provides broad context for selected general developmental skills expected in the first 2 years of life. The table summarizes age ranges during which 50–75 percent of youth achieve the various skills.

Of course, it is important to recognize and acknowledge that development is not complete at 2 years of age. Progress in each of the above four domains continues at the very least into early adulthood and perhaps beyond. In addition to the basic milestones in each domain listed in Table 3-2, more advanced or higher-order skills emerge over this extended timeframe. Children progress from learning and using words to engaging in simple conversations by age 3, repairing conversational breakdowns when not understood by age 4, and engaging in storytelling and more complex conversation by age 5 (ASHA, n.d.; CDC, 2023a). Similarly, many cognitive skills, particularly within the domain of executive functioning (e.g., impulse control, planning, problem solving, and decision making) are not fully developed until early adulthood, and the developmental trajectories of executive function extend from adolescence to old age (Best and Miller, 2010; Ferguson et al., 2021). It is exceptionally important to understand this continued developmental progress in children who may be at risk for altered developmental trajectories, including those born LBW or preterm.

ALTERED DEVELOPMENTAL PROGRESS

The most common alteration in developmental progress is a delay, whereby a child acquires skills more slowly compared with same-aged peers. However, some children may experience other alterations—for example, deviations in development, when a child develops skills out of the usual sequence, such as crawling before sitting or saying words before understanding their meaning. “Dissociation” is the term used when a child has differing rates of development in different developmental domains. For example, a child with delays in language development may have normal motor development, or a child with motor delays may have normal

TABLE 3-2 Selected Developmental Skills from Birth to 24 Months

| Age | Movement or Physical Development | Communication | Cognition | Social or Emotional Development |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| By 2 months | Holds up head when on tummy. Moves both arms and legs. Opens hands briefly. |

Startles at loud sounds. | Watches when others move. Looks at a toy for a few seconds. |

Quiets or smiles when talked to. Smiles at people. Looks at faces. Moves or makes sounds to get someone’s attention. |

| By 4 months | Holds a toy in hands. Holds head steady when in supported seated position. |

Seems to recognize your voice. Quiets if crying. Cries change for different needs. Makes cooing sounds. Turns head toward voice. |

If hungry, opens mouth when sees bottle. Explores hands. |

Smiles, moves, makes sounds to get or keep attention. Chuckles when prompted by something (e.g., funny face). |

| By 6 months | Rolls from tummy to back. Pushes up on arms when on tummy. Leans on hands to support self when seated. |

Moves eyes in the direction of sounds. Pays attention to music. Babbles long strings of sounds, such as mimi upup babababa. Takes turn making sounds with others. |

Notices toys that make sounds. Reaches for desired toys. Puts objects in mouth to explore. |

Responds to changes in tone of voice. Looks at self in mirror. Recognizes familiar people. Laughs. |

| By 9 monthsa | Gets into seated position by self. Sits without support. Moves items from one hand to another. Uses fingers to rake food toward self. |

Looks for objects when dropped out of sight. Bangs two objects together. |

May be shy/clingy when around strangers. Reacts when caregiver leaves. Responds to name. Shows several facial expressions for different moods. Points to objects and shows them to others. |

| By 12 months | Pulls to stand. “Cruises” while holding onto furniture. Drinks from a cup when held. |

Understands words for common items and people—words such as cup, truck, juice, and daddy. Starts to respond to simple words and phrases, such as “No,” “Come here,” and “Want more?” Listens to songs and stories for a short time. Uses gestures, such as waving bye, reaching for “up,” and shaking head no. Imitates different speech sounds Says one or two words, such as hi, dog, dada, mama, or uh-oh. This will happen around their first birthday, but sounds may not be clear. |

Puts items into containers. Looks for things seen hidden, such as a toy under a blanket. |

Plays games, such as peek-a-boo and pat-a-cake. |

| By 18 months | Walks independently. Drinks from open cup. Tries to use a spoon. Climbs onto/off furniture. Scribbles. |

Follows one-part directions, such as “Roll the ball” or “Kiss the baby.” Listens to simple stories, songs, and rhymes. |

Tries to use items in correct way. Stacks objects. Matches basic shapes/colors. |

Copies actions of others. Shows toys to others. Engages in simple pretend play (e.g., hugging baby doll). Shows others affection. Points to share objects/experiences of interest. Notices emotional response of others. |

| Age | Movement or Physical Development | Communication | Cognition | Social or Emotional Development |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| By 24 months | Kicks a ball. Runs. Walks up a few stairs with or without help. Eats with a spoon. |

Points to pictures in a book when named. Uses p, b, m, h, and w in words. Points to a few body parts when asked. Responds to simple questions, such as “Who’s that?” or “Where’s your shoe?” Uses a lot of new words. Starts to name pictures in books. Asks questions, such as “What’s that?”, “Who’s that?”, and “Where’s kitty?” Puts two words together, such as “more apple,” “no bed,” and “mommy book.” |

Holds item in one hand while using the other. Tries to use switches, knobs, or buttons on a toy. Plays with more than one toy at the same time. |

Looks to caregiver’s face when in new situations. Notices when others are hurt or upset. |

a The 75th percentile for crawling is 9.3 months (WHO, 2006). Notably, crawling was removed from the updated CDC/AAP milestones (CDC, 2023a) based on scarce normative data, inconsistency in definitions, variability in timing of onset, and lack of evidence that all typically developing children crawl (Kretch et al., 2022, citing J. Zubler, p. 445). For this reason the committee has not included crawling in the present table. It should be noted that, while the absence of crawling is not a developmental concern, atypical crawling may indicate a motor disability.

SOURCES: ASHA, 2015; CDC, 2023a

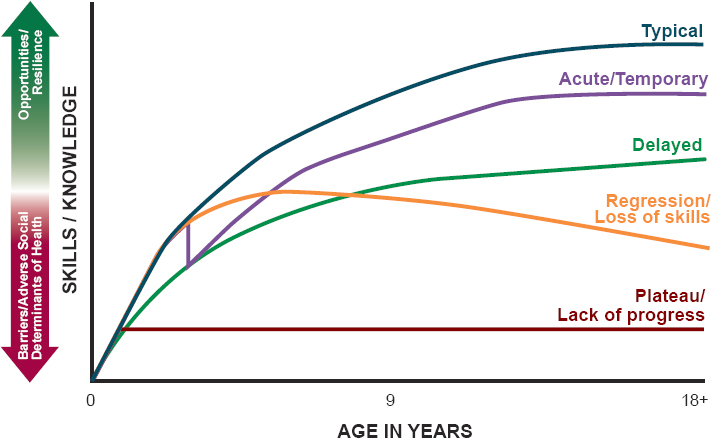

language function. “Regression” is the loss of developmental skills. It is less common than “dissociation” and suggests a serious ongoing problem that can be medical, neurological, or environmental (including social) in origin (Capute and Accardo, 1996). Acute injury or illness can cause a temporary regression in developmental skills. In some cases, such as a mild concussion, the child can have complete recovery and return to full baseline functioning. However, in most instances, any neurological injury or central nervous system illness will cause an acute change in function, and the child will then return to a more typical rate of developmental progress, although there may be some residual deficit. Figure 3-1 depicts typical, or average, and altered developmental trajectories.

The protracted developmental timeline for higher-order cognitive skills can be impacted by any early deviation from typical development and result in a child’s “growing into the deficit.” That is, the full impact of altered developmental trajectories may not be appreciated until a child reaches the age at which the acquisition of higher-level skills is expected, but the disruption in development can occur at any point in time. Even within the first years of life, typical developmental progress can be interrupted or impeded by various factors, genetic, medical, psychosocial, and environmental. Any early disruption can thus have lifelong consequences

with regard to cognitive developmental achievement (Anderson et al., 2005; Dennis, 2000; Pascoe et al., 2021; Taylor et al., 2004).

As indicated in other chapters of this report, myriad factors, including various genetic and medical conditions, contribute to the occurrence of LBW and preterm birth. These factors obviously disrupt the standard biological developmental process, potentially resulting in structural neuroanatomic differences (e.g., via intraventricular hemorrhage) or chronic health conditions that will persistently impact development (e.g., epilepsy) (Dennis, 2000; Pascoe et al., 2021; Taylor et al., 2004). Additionally, preterm birth results in a significant environmental change in that infants leave the protective environment of the womb earlier than they should, exposing them to various patterns of stimulation (e.g., lights and sounds) well before their bodies are ready to process that type and degree of stimulation (Almadhoob and Ohlsson, 2015; Kent et al., 2002; Lai and Bearer, 2008; Morag and Ohlsson, 2016; Wachman and Lahav, 2011; Williams et al., 2018). The integrity of the prenatal environment also is important, as it is well documented that the health and well-being of the mother are imperative for optimal infant prenatal physical development (Gray et al., 2004; Petterson and Albers, 2001).

Optimal development depends critically on the child’s health and postnatal environment and experiences such as enriched stimulation. In an attempt to monitor and improve outcomes for those born preterm or LBW, developmental follow-up clinics were established as a gold standard component of care for this population. Unfortunately, there are known disparities in access to these follow-up clinics on the basis of location (e.g., urban versus rural), structural racism, and socioeconomic status, although research on the latter is mixed (Fraiman et al., 2022; Fuller et al., 2023; Harmon et al., 2013; Roberts et al., 2016; Swearingen et al., 2020). In addition, eligibility criteria for high-risk infant follow-up clinics vary, resulting in unequal access among LBW infants (Litt and Campbell, 2023). As a result, many infants and families may not receive this careful monitoring.

Research has identified aspects of the home and neighborhood environment that are strongly associated with broad developmental outcomes (Manduca and Sampson, 2019). Factors often identified as social determinants of health, such as a child’s access to enriching resources within the home, school, and community, are strongly related to functional achievement (Davis-Kean, 2005; Shifrer et al., 2011). Children who live in poverty or are of lower socioeconomic status have reduced academic achievement, and there is even some evidence for their having differential patterns of neuroanatomical structural development (Farah et al., 2006; Hackman and Farah, 2009).

The impact of these biological, health, and social factors on developmental outcomes will vary depending on each child’s unique experience, resulting in various patterns of altered development as depicted in Figure 3-1. It is

important to keep in mind that this figure depicts hypothetical patterns of altered global development. A child may demonstrate different patterns over the course of development, as well as disparate patterns of development in one domain compared with another. If disruption or alteration of developmental progress is identified early, appropriate interventions can be implemented to minimize the disruption and optimize future levels of functional independence (Hill et al., 2003).

DEVELOPMENTAL TIMELINES FOR PRETERM AND SMALL FOR GESTATIONAL AGE LOW BIRTH WEIGHT INFANTS

Developmental delays are evidenced when children demonstrate skills or functions that are below norms based on their age. That is, children should be identified as having a delay when they have not acquired a series of developmental skills as expected in the typical or average timeline described in the preceding section. The CDC estimates that one in six children between the ages of 3 and 17 years have a developmental disability, ranging from mild to severe (Cogswell et al., 2022). Children with increased risk for disability, such as those born LBW or preterm, have higher rates.

Worldwide, it is estimated that approximately 7 percent of all children born prior to 37 weeks gestation will experience long-term neurodevelopmental impairments or disability (Blencowe et al., 2013). Moderate to severe neurodevelopmental impairment are often defined as cognitive and/or motor scores below the 2nd percentile on standardized tests of development, bilateral blindness, hearing loss, and/or varying degrees of cerebral palsy (Adams-Chapman et al., 2018). The risk of impairment increases with birth at earlier gestational ages, with an estimated 24 percent of children born at 28–31 weeks and up to 52 percent of those born prior to 28 weeks showing impairment (Blencowe et al., 2013).

Preterm infants qualitatively demonstrate delays in development within the first months of life, particularly compared with term infants of the same chronological age (see below for the meaning of “chronological age”). Delays have been noted across all domains of development (movement or physical development, communication, cognition, and social or emotional development). For these infants, progress in all domains and overall functioning require close monitoring and therapeutic intervention for optimal development (Scharf et al., 2016; Spittle et al., 2015). Early identification of developmental delays is important so that appropriate interventions can be initiated as soon as possible, leading to improved outcomes: In general, the earlier an intervention is provided the more effective it is likely to be (CDC, 2023c; Center on the Developing Child, 2008, 2010; Damiano and Longo, 2021; Halfon and Forrest, 2017; Hill et al., 2003; NECTAC, 2011;Whitehouse et al., 2021). As noted previously, the degree of delay

across domains of development may vary depending on medical and environmental factors, and sequential assessments over time are important for identification of developmental delays.

For children born LBW, the determination of a delay is complicated by various and altered developmental trajectories, as well as inconsistency and debate with respect to normative data for infants born preterm. Given the altered and nonlinear development in the preterm population for nearly 20 years, Marlow and colleagues (2005) found that determination of a delay at one age is not indicative of a fixed or stable delay across time. In fact, among children born extremely preterm who were not classified as having a delay at 30 months corrected age, nearly one in four (24 percent) were classified as having a moderate or severe disability at 6 years of age. Within the past 10 years, research has revealed that the classification of delay by a popular standardized test of early childhood development, the Bayley Scales, is not stable over the first 2 years of life for very LBW infants. One in six very LBW infants who did not demonstrate language delays in the first year of life demonstrated delays in the second year (Greene et al., 2013). Adding to the complexity of varied and altered developmental trajectories is inconsistent guidance regarding the normative data, corrected versus chronological, against which their development should be compared.

Corrected versus Chronological Age

Children born LBW are usually born preterm or earlier than anticipated. To acknowledge the impact of preterm birth on skill attainment, the developmental trajectory of preterm children is compared with a “corrected age” rather than their actual chronological age.

To account for early birth, it is standard practice to subtract the degree of prematurity in weeks from a child’s chronological age until 24–36 months (Engle, 2004). Thus, for example, a child born at 28 weeks gestation presenting for an evaluation 12 months postbirth will be compared against developmental expectations for a 9-month-old (12 months–12 weeks preterm birth) rather than those for a 12-month-old (Bayley and Aylward, 2019). In addition, growth parameters are corrected until age 24–36 months, allowing height, weight, and head circumference to demonstrate “catch-up” growth, which parallels optimal development (Dusick et al., 2003; Ghods et al., 2011; van Dommelen et al., 2014).

The primary rationale for the use of corrected age when evaluating development in LBW or preterm children is that not correcting would place them at a greater disadvantage regarding estimates of their developmental level. In short, without age correction, LBW or preterm infants will have lower developmental scores compared with their peers of the same chronological age. These scores can be viewed as artificially low on the grounds that LBW or preterm infants should not be expected to achieve skills at

the same rate as a child who has had the full 37–40 weeks gestational period. Take, for example, an infant born at 24 weeks gestational age who has reached 6 months of chronological age. Based on the chronological age of 6 months, families and caregivers may be expecting this child to begin sitting propped on their hands or sitting independently and to start babbling. However, if this same child were born full term, they would have been ex utero for only 2 months, an age at which independent sitting and/or babbling would be unexpected. Correcting for age thus provides a way to accommodate the missed in utero neurodevelopmental opportunities of the preterm child. Accordingly, Aylward (2020) suggests that the procedure for age correction is based on the idea of a “maturational catch-up.” By extension, not correcting for prematurity may be conceptualized as qualifying children for intervention services that are not needed (Aylward, 2020).

Unfortunately, standards and recommendations vary regarding the use of corrected age in considering the developmental outcomes of children born preterm. The primary standardized developmental measures used with infants and very young children (Bayley and Aylward, 2019; Mullen, 1995) recommend age correction until 2 years postbirth. Some, however, including the AAP, advocate for correcting until age 3 years (Engle, 2004) or even school age (Wehrle et al., 2021). Moreover, there are debates over whether age correction should be used for all developmental domains (e.g., motor, language, and cognitive) equally, or its application should vary across domains and/or based on degree of prematurity (Aylward, 2020; Doyle and Anderson, 2016). For example, when assessing cognitive domains, Aylward (2020) advocates for use of corrected age for all children born preterm until 2 years of age and use of corrected age until 3 years of age for children born 4 months prematurely. Aylward also recommends correcting until 3 years of age for language and motor assessment for all children born preterm.

Correcting for prematurity results in higher scores than use of chronological age from 6 months to 16 years of age (Wilson-Ching et al., 2014). More specifically, van Veen and colleagues (2016) found that use of corrected-age norms resulted in significantly higher IQ scores, as much as 1 standard deviation higher, even at age 5 years. More recently, Wehrle and colleagues (2021) revealed that corrected-age norms produced scores .04–.18 of a standard deviation higher than uncorrected scores from 7 to 13 years of age.

Given the higher scores produced by correcting for prematurity, it is acknowledged that using corrected ages may mask or minimize delays (Doyle and Anderson, 2016). In fact, using corrected age may simply be ignoring the developmental injury that occurs with LBW or preterm birth. Children who have “normal” scores compared with corrected-age norms may have scores well below average compared with chronological-age norms. If the corrected-age scores are used, these children will not qualify for intervention services (Parekh et al., 2016).

The ultimate questions regarding this issue, as yet to be definitively answered by the research literature, are what proportion of LBW or preterm children actually attain age-expected skills at some point in time, and at what point in their developmental trajectory this level of skill attainment should be expected. If corrected-age norms are used beyond the time at which they should be used, the intervention needs of LBW or preterm children risk being underidentified. The possible impact of this finding is that children entering school will not be appropriately identified for needed supports on the basis of the gestational age at which they were born. Use of corrected-age norms may accurately depict the developmental level at which a child is demonstrating skills, but it will not accurately reflect the degree to which they need support to attain skills consistent with their same-chronological-age peers, with whom they will be attending school. Ambiguity in clinical practice and the research literature has led some experts to conclude that researchers should report corrected-age scores and that clinicians and/or caregivers should use scores that best meet the needs of the child (Doyle and Anderson, 2016). An extension of this conclusion may be that clinicians should report both corrected and uncorrected age, with eligibility and need for clinical intervention based on uncorrected age.

When Do Delays Become Disorders?

The identification of appropriate normative comparisons also impacts the determination of a disorder versus a delay in development. Again, a delay is identified when a child does not demonstrate a skill at the time point at which this skill generally is observed in other same-aged children (Khan and Leventhal, 2023); however, it is still anticipated that the child will eventually attain that skill. A disorder (or “disability”), in contrast, either indicates persistent inability to demonstrate a skill without evidence of developmental skill progression and with evidence of functional limitations, or a qualitative skill difference or skill atypicality.5 Identification of a disorder often results in a medical diagnosis.

Examples from the motor and language development literature illustrate the distinctions between delays and atypicalities. The motor development literature documents the distinction between motor delays and diagnosable motor disorders, the latter taking the form of (1) persistent motor delays without evidence of progression and with evidence of functional limitations, or (2) qualitative motor differences in the form of atypicalities.6 For example, a child born prematurely who is not walking independently at 18 months corrected age is considered to have a motor delay (see

___________________

5 42 U.S. Code § 15002.

6 The committee chose the word “atypicalities” to denote differences that are unexpected at any age or stage of development.

Table 3-2), but may ultimately go on to achieve this milestone and walk, albeit at a later age than would typically be expected. In contrast, a child with neonatal reflexes, such as an asymmetrical tonic neck reflex, that are anticipated to disappear at 3–9 months of age but persist at 9 months and interfere with visual tracking, attention, and adaptive play is showing signs of a motor disorder in the form of cerebral palsy (Arcilla and Vilella, 2023; Blondis, 2004; Hamer and Hadders-Algra, 2016; Zafeiriou, 2004). Similarly, a child who crosses their legs like “scissors” upon being picked up at any age or does not have voluntary control over a certain set of lateral extremities (i.e., left or right side) or upper or lower extremities (i.e., arms or legs) when crawling is demonstrating motor atypicalities that are not anticipated at any age or stage of development and are consistent with a diagnosis of cerebral palsy (Blondis, 2004; Zafeiriou, 2004).

The language development literature does not provide the same definitive guidance and precise diagnostic recommendations currently found in the literature on motor development. However, the same distinction between delays and disorders (in the form of persistent delays with functional limitations or atypicalities) exists across language development. Specifically, inability to use two or more words, including one action word, together at 30 months of age is considered a language delay (see Table 3-2). Alternatively, articulation errors are common in children under 4 years of age as they achieve verbal fluency; however, if this behavior persists beyond this stage as children mature, and if their intelligibility is negatively impacted, they are likely to be diagnosed with a speech disorder (ASHA, n.d.; Hustad et al., 2021). Distinct from persistent delays and representing deviations in development, high-pitched, stereotyped, and repetitive screeching and squealing are examples of language atypicalities that are not anticipated at any age or stage of development and are suggestive of a disorder, such as autism spectrum disorder (Vogindroukas et al., 2022). Similarly, because receptive language development typically precedes expressive language development, significantly higher scores on expressive than on receptive language on standardized testing are not anticipated at any age or stage of development, and instead are a sign of memorized phrases (i.e., scripting), sometimes seen in autism spectrum disorder (Vogindroukas et al., 2022).

In some intervention settings, systems, and institutions, the concept of a persistent delay meeting criteria for a disorder is formally, or informally, bound by a child’s age. For example, under IDEA Part C, in children aged birth to 3 years, documentation of a developmental delay is one of two criteria for eligibility for services. Older children, under IDEA Part B, may be eligible for special education services under the criterion of “significant developmental delay” until age 9. After that age, to continue receiving services, a child must qualify for services under one of the IDEA disability categories. Similarly, there is emerging, albeit informal, consensus among practitioners in the domain of speech-language pathology that a

speech-language delay that has not resolved by 5 years of age has exceeded the temporal threshold for delay and represents a disorder.

In some institutional paradigms and systems of care, a diagnosis of a disorder also requires demonstration of some degree of functional limitation. For example, the American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities defines intellectual disability as “a condition characterized by significant limitations in both intellectual functioning and adaptive behavior that originates before the age of 22” (AAIDD, 2023). Similarly, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-5-TR) incorporates functional limitation into the criteria for intellectual developmental disorder and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (see below), among others (APA, 2013).

In some cases, disorders are also defined by the quantitative degree of impairment, or specific criteria that must be demonstrated, in addition to functional limitations. Examples of such disorders from the DSM-5-TR include

- Intellectual developmental disorder, which requires demonstration of a 2 standard deviation gap between an individual’s performance on a standardized measure of IQ or adaptive functioning and that of same-aged typically developing peers; and

- Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, which requires report of a set of behavioral symptoms that have persisted for more than 6 months in two or more settings that cause functional limitations in some manner.

Other disorders are defined by qualitative and relative interpretation of symptoms in addition to functional limitations. Examples of these disorders from the DSM-5-TR include

- Developmental coordination disorder, which is defined in part as the performance of coordinated motor skills significantly below expectation for a child’s chronological age or intellectual ability, which significantly interferes with daily functioning;

- Language disorder, defined as a pattern of persistent difficulties in the comprehension and production of spoken, written, or signed language relative to age and cognitive abilities that interfere with functioning; and

- Specific learning disorders, defined as a pattern of learning difficulties substantially below what would be expected based on age, grade placement, and cognitive ability that persist after 6 months of targeted treatment and interfere with daily functioning.7

___________________

7 Of note, quantitative guidelines were previously applied in determining whether specific learning disorders met criteria for a disorder. Discrepancy-based models of learning disorders, still used by some diagnosticians, continue to define such disorders as the presence of a significant difference, often greater than 1 standard deviation, between cognitive abilities and academic achievement.

Chapter 4 provides information on some of the disorders and health conditions that may be associated with preterm or small for gestational age birth. For infants who qualify for SSI benefits based on the LBW listing, these conditions may provide alternative diagnoses by which such children may continue to qualify for SSI following a Continuing Disability Review.

FINDINGS AND CONCLUSIONS

Findings

3-1. Developmental skills provide the scaffolding for function.

3-2. Development refers to an active process that depends on the interaction between the development of various physiological and organ systems and experiences and the environment in the context of genetic and epigenetic factors. Neurodevelopment is an active and progressive process that depends on the formation of neural networks in the nervous system, which in turn depends on a developing child’s physical and psychosocial environments, beginning in utero and continuing after birth.

3-3. Developmental skills typically are grouped into developmental domains, while functional skills are grouped into functional domains. Although there are similarities in terminology across some of the developmental and functional domains, there seldom is a one-to-one correspondence.

3-4. Skills in all developmental domains will impact skills in all functional domains, especially over time.

3-5. Assuming a typical developmental trajectory, a child’s attainment of skills within the first years of life is rapid and expansive, but the development of new skills continues at least into early adulthood.

3-6. Anything that interferes with an environment conducive to typical development can negatively affect a child’s development, potentially resulting in delayed development or ongoing health conditions.

3-7. When a child has a health condition or impairment that impedes skill development, it negatively affects functioning.

3-8. Approximately 7 percent of children worldwide who are born prior to 37 weeks gestation will have some moderate to severe delay in the form of neurodevelopmental impairment.

3-9. The risk of impairment among children born preterm increases with birth at earlier gestational ages, with an estimated 24 percent of children born prior to 31 weeks and up to 52 percent of those born prior to 28 weeks showing impairments.

3-10. Infants who are born preterm often require intensive and/or extended hospitalization, which significantly limits their ability to participate in the family unit and impedes normal developmental and growth trajectories.

3-11. Health care providers use developmental milestones in developmental surveillance and screening of infants and children, especially during well-child visits, to identify those with delays or other atypical development.

3-12. In individual children, skills may emerge at different rates in different developmental domains (e.g., movement or physical, communication, cognitive, or social or emotional). More advanced or higher-order skills emerge over the course of development into adulthood.

3-13. Children who receive formal diagnoses pertaining to the acquisition of developmental skills and functioning fall in one of two broad categories: (1) those with delays in skill attainment relative to peers that persist and result in altered functioning, and (2) those with developmental skill attainment or functional skills that are considered atypical, or unexpected, at any age.

3-14. Correcting age for prematurity until 2–3 years of age is a common practice; however, this practice is not consistent in clinical application and is the subject of controversy. Correcting for prematurity may result in elevated developmental test scores in children with impairments in developmental skill attainment and functioning who will remain behind throughout the lifespan or have an altered developmental trajectory relative to their peers of the same chronological age, thereby delaying or denying eligibility for services these children need.

3-15. The longer developmental timeline for higher-order, or advanced, cognitive skills can be impacted by any early deviation from typical development. The full impact of altered developmental trajectories may not be fully appreciated until a child reaches the age at which acquisition of the higher-order skills is expected.

3-16. Delays in development and impairments can adversely affect a child’s transition from typical childhood dependence to adult independence.

Conclusions

3-1. Disruption of development because of LBW or preterm birth can result in persistent altered developmental trajectories that will impact the degree of independence attained in adulthood.

3-2. Development can be disrupted by genetic, medical, environmental, and psychosocial factors, including those identified as social determinants of health.

3-3. Skills in all domains, as well as overall functioning, require close monitoring and prompt therapeutic intervention when delays or atypicalities are detected.

3-4. Developmental outcomes may be improved by early screening and identification, which can lead to early implementation of effective interventions.

3-5. Some developmental problems, particularly those involving higher-order cognitive skills, may not be identified until a later age, when they are expected to appear, although the underlying neurobiological cause of the difficulties may be related to experiences in utero or at birth.

REFERENCES

AAIDD (American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities). 2023. Defining criteria for intellectual disability. https://www.aaidd.org/intellectual-disability/definition (accessed October 9, 2023).

Adams-Chapman, I., R. J. Heyne, S. B. DeMauro, A. F. Duncan, S. R. Hintz, A. Pappas, B. R. Vohr, S. A. McDonald, A. Das, J. E. Newman, and R. D. Higgins. 2018. Neurodevelopmental impairment among extremely preterm infants in the Neonatal Research Network. Pediatrics 141(5):e20173091.

Almadhoob, A., and A. Ohlsson. 2015. Sound reduction management in the neonatal intensive care unit for preterm or very low birth weight infants. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 30(1):CD010333.

Anderson, V., C. Catroppa, S. Morse, F. Haritou, and J. Rosenfeld. 2005. Functional plasticity or vulnerability after early brain injury? Pediatrics 116(6):1374–1382.

APA (American Psychiatric Association). 2013. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition, text revision DSM-5-TR (DSM-5-TR), 5th ed. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787.

Arcilla, C. K., and R. C. Vilella. 2023. Tonic neck reflex. In StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing.

ASHA (American Speech-Language-Hearing Association). 2015. How does your child hear and talk? https://www.asha.org/public/speech/development/chart (accessed July 10, 2023).

ASHA. n.d. Speech sound disorders: Articulation and phonology. www.asha.org/Practice-Portal/Clinical-Topics/Articulation-and-Phonology (accessed July 25, 2023).

Aylward, G. P. 2020. Is it correct to correct for prematurity? Theoretic analysis of the Bayley-4 normative data. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics 41(2):128–133.

Bayley, N., and G. P. Aylward. 2019. Bayley-4: Scales of infant and toddler development. Coushatta, LA: Pearson Assessments.

Best, J. R., and P. H. Miller. 2010. A developmental perspective on executive function. Child Development 81(6):1641–1660.

Blencowe, H., A. C. Lee, S. Cousens, A. Bahalim, R. Narwal, N. Zhong, D. Chou, L. Say, N. Modi, J. Katz, T. Vos, N. Marlow, and J. E. Lawn. 2013. Preterm birth–associated neurodevelopmental impairment estimates at regional and global levels for 2010. Pediatric Research 74(S1):17–34.

Blondis, T. A. 2004. Cerebral palsy and neuromuscular diseases. In Developmental motor disorders: A neuropsychological perspective, edited by D. Dewey and D. E. Tupper. New York: The Guilford Press. Pp. 113–136.

Capute, A., and P. Accardo. 1996. A neurodevelopmental perspective on the continuum of developmental disabilities. In Developmental disabilities in infancy and childhood, Vol. 1 Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing. Pp. 1–22.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2023a. CDC’s developmental milestones. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/actearly/milestones/index.html (accessed July 10, 2023).

CDC. 2023b. Learn the signs. Act early. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/actearly/index.html (accessed July 10, 2023).

CDC. 2023c. Why act early if you’re concerned about development? https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/actearly/whyActEarly.html (accessed January 4, 2024).

Center on the Developing Child. 2008. InBrief: The science of early childhood development. https://developingchild.harvard.edu/resources/inbrief-science-of-ecd (accessed January 4, 2024).

Center on the Developing Child. 2010. The foundations of lifelong health are built in early childhood. https://developingchild.harvard.edu/resources/the-foundations-of-lifelong-health-are-built-in-early-childhood (accessed January 4, 2024).

Cheong, J. L., A. C. Burnett, K. Treyvaud, and A. J. Spittle. 2020. Early environment and long-term outcomes of preterm infants. Journal of Neural Transmission 127(1):1–8.

Cogswell, M. E., E. Coil, L. H. Tian, S. C. Tinker, A. B. Ryerson, M. J. Maenner, C. E. Rice, and G. Peacock. 2022. Health needs and use of services among children with developmental disabilities—United States, 2014–2018. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 71(12):453.

Damiano, D. L., and E. Longo. 2021. Early intervention evidence for infants with or at risk for cerebral palsy: An overview of systematic reviews. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology 63(7):771–784.

Davidson, J. E., R. A. Aslakson, A. C. Long, K. A. Puntillo, E. K. Kross, J. Hart, C. E. Cox, H. Wunsch, M. A. Wickline, M. E. Nunnally, G. Netzer, N. Kentish-Barnes, C. L. Sprung, C. S. Hartog, M. Coombs, R. T. Gerritsen, R. O. Hopkins, L. S. Franck, Y. Skrobik, A. A. Kon, E. A. Scruth, M. A. Harvey, M. Lewis-Newby, D. B. White, S. M. Swoboda, C. R. Cooke, M. M. Levy, E. Azoulay, and J. R. Curtis. 2017. Guidelines for family-centered care in the neonatal, pediatric, and adult ICU. Critical Care Medicine 45(1):103–128.

Davis-Kean, P. E. 2005. The influence of parent education and family income on child achievement: The indirect role of parental expectations and the home environment. Journal of Family Psychology 19(2):294–304.

Dennis, M. 2000. Developmental plasticity in children: The role of biological risk, development, time, and reserve. Journal of Communication Disorders 33(4):321–332.

Dodd, B. 2011. Differentiating speech delay from disorder: Does it matter? Topics in Language Disorders 31(2):96-111.

Doyle, L. W., and P. J. Anderson. 2016. Do we need to correct age for prematurity when assessing children? The Journal of Pediatrics 173:11–12.

Dusick, A. M., B. B. Poindexter, R. A. Ehrenkranz, and J. A. Lemons. 2003. Growth failure in the preterm infant: Can we catch up? Seminars in Perinatology 27(4):302–310.

Engle, W. A. 2004. Age terminology during the perinatal period. Pediatrics 114(5):1362–1364.

Farah, M. J., D. M. Shera, J. H. Savage, L. Betancourt, J. M. Giannetta, N. L. Brodsky, E. K. Malmud, and H. Hurt. 2006. Childhood poverty: Specific associations with neurocognitive development. Brain Research 1110(1):166–174.

Ferguson, H. J., V. E. A. Brunsdon, and E. E. F. Bradford. 2021. The developmental trajectories of executive function from adolescence to old age. Scientific Reports 11(1):1382. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/33446798 (accessed January 1, 2023).

Fraiman, Y. S., J. E. Stewart, and J. S. Litt. 2022. Race, language, and neighborhood predict high-risk preterm infant follow up program participation. Journal of Perinatology 42(2):217–222.

Franck, L. S., C. Waddington, and K. O’Brien. 2020. Family integrated care for preterm infants. Critical Care Nursing Clinics of North America 32(2):149–165.

Fuller, M. G., T. Lu, E. E. Gray, M. A. L. Jocson, M. K. Barger, M. Bennett, H. C. Lee, and S. R. Hintz. 2023. Rural residence and factors associated with attendance at the second high-risk infant follow-up clinic visit for very low birth weight infants in California. American Journal of Perinatology 40(5):546–556.

Gesell, A. 1925. Monthly increments of development in infancy. The Pedagogical Seminary and Journal of Genetic Psychology 32(2):203–208.

Ghods, E., A. Kreissl, S. Brandstetter, R. Fuiko, and K. Widhalm. 2011. Head circumference catch-up growth among preterm very low birth weight infants: Effect on neurodevelopmental outcome. Journal of Perinatal Medicine 39(5):579–586.

Gray, R. F., A. Indurkhya, and M. C. McCormick. 2004. Prevalence, stability, and predictors of clinically significant behavior problems in low birth weight children at 3, 5, and 8 years of age. Pediatrics 114(3):736–743.

Greene, M. M., K. Patra, J. M. Silvestri, and M. N. Nelson. 2013. Re-evaluating preterm infants with the Bayley-III: Patterns and predictors of change. Research in Developmental Disabilities 34(7):2107–2117.

Hackman, D. A., and M. J. Farah. 2009. Socioeconomic status and the developing brain. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 13(2):65–73.

Hagan, J. F., J. Shaw, and P. Duncan. 2017. Bright futures. Itasca, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics.

Halfon, N., and C. B. Forrest. 2017. The emerging theoretical framework of life course health development. In Handbook of life course health development [Internet], edited by N. Halfon, C. B. Forrest, R. M. Lerner, and E. M. Faustman. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2018. Pp. 19–43.

Hamer, E. G., and M. Hadders-Algra. 2016. Prognostic significance of neurological signs in high-risk infants: A systematic review. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology 58(S4):53–60.

Harmon, S. L., M. Conaway, R. A. Sinkin, and J. A. Blackman. 2013. Factors associated with neonatal intensive care follow-up appointment compliance. Clinical Pediatrics 52(5):389–396.

Hill, J. L., J. Brooks-Gunn, and J. Waldfogel. 2003. Sustained effects of high participation in an early intervention for low-birth-weight premature infants. Developmental Psychology 39(4):730–744.

Hustad, K. C., T. J. Mahr, P. Natzke, and P. J. Rathouz. 2021. Speech development between 30 and 119 months in typical children I: Intelligibility growth curves for single-word and multiword productions. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 64(10):3707–3719.

Kent, W. D., A. K. Tan, M. C. Clarke, and T. Bardell. 2002. Excessive noise levels in the neonatal ICU: Potential effects on auditory system development. Journal of Otolaryngology 31(6):355–360.

Khan, I., and B. L. Leventhal. 2023. Developmental delay. In StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing.

Kretch, K. S., S. L. Willett, L.-Y. Hsu, B. A. Sargent, R. T. Harbourne, and S. C. Dusing. 2022. “Learn the signs. Act early.”: Updates and implications for physical therapists. Pediatric Physical Therapy 34(4):440–448.

Lai, T. T., and C. F. Bearer. 2008. Iatrogenic environmental hazards in the neonatal intensive care unit. Clinics in Perinatology 35(1):163–181.

Lipkin, P. H., and M. M. Macias. 2020. Promoting optimal development: Identifying infants and young children with developmental disorders through developmental surveillance and screening. Pediatrics 145(1):e20193449.

Litt, J. S., and D. E. Campbell. 2023. High-risk infant follow-up after NICU discharge: Current care models and future considerations. Clinics in Perinatology 50(1):225–238.

Manduca, R., and R. J. Sampson. 2019. Punishing and toxic neighborhood environments independently predict the intergenerational social mobility of Black and White children. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116(16):7772–7777.

Marlow, N., D. Wolke, M. A. Bracewell, and M. Samara. 2005. Neurologic and developmental disability at six years of age after extremely preterm birth. New England Journal of Medicine 352(1):9–19.

Morag, I., and A. Ohlsson. 2016. Cycled light in the intensive care unit for preterm and low birth weight infants. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 8:CD006982.

Mullen, E. M. 1995. Mullen scales of early learning. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service.

NECTAC (National Early Childhood Technical Assistance Center). 2011. The importance of early intervention for infants and toddlers with disabilities and their families. https://ectacenter.org/~pdfs/pubs/importanceofearlyintervention.pdf (accessed January 25, 2024).

Parekh, S. A., E. M. Boyle, A. Guy, S. Blaggan, B. N. Manktelow, D. Wolke, and S. Johnson. 2016. Correcting for prematurity affects developmental test scores in infants born late and moderately preterm. Early Human Development 94:1–6.

Pascoe, L., A. C. Burnett, and P. J. Anderson. 2021. Cognitive and academic outcomes of children born extremely preterm. Seminars in Perinatology 45(8):e151480.

Petterson, S. M., and A. B. Albers. 2001. Effects of poverty and maternal depression on early child development. Child Development 72(6):1794–1813.

Roberts, H. J., R. M. Harris, C. Krehbiel, B. Banks, B. Jackson, and H. Needelman. 2016. Examining disparities in the long term follow-up of neonatal intensive care unit graduates in Nebraska, U.S.A. Journal of Neonatal Nursing 22(5):250–256.

Scharf, R. J., G. J. Scharf, and A. Stroustrup. 2016. Developmental milestones. Pediatrics in Review 37(1):25–37.

Shifrer, D., C. Muller, and R. Callahan. 2011. Disproportionality and learning disabilities: Parsing apart race, socioeconomic status, and language. Journal of Learning Disabilities 44(3):246–257.

Spittle, A., J. Orton, P. J. Anderson, R. Boyd, and L. W. Doyle. 2015. Early developmental intervention programmes provided post hospital discharge to prevent motor and cognitive impairment in preterm infants. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015(11):Cd005495.

SSA (Social Security Administration). 2023. Disability evaluation under Social Security—100.00 low birth weight and failure to thrive—Childhood. https://www.ssa.gov/disability/professionals/bluebook/100.00-GrowthImpairment-Childhood.htm (accessed August 7, 2023).

Subedi, D., M. D. DeBoer, and R. J. Scharf. 2017. Developmental trajectories in children with prolonged NICU stays. Archives of Disease in Childhood 102(1):29–34.

Swearingen, C., P. Simpson, E. Cabacungan, and S. Cohen. 2020. Social disparities negatively impact neonatal follow-up clinic attendance of premature infants discharged from the neonatal intensive care unit. Journal of Perinatology 40(5):790–797.

Taylor, H. G., N. Minich, B. Bangert, P. A. Filipek, and M. Hack. 2004. Long-term neuropsychological outcomes of very low birth weight: Associations with early risks for periventricular brain insults. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society 10(7):987–1004.

van Dommelen, P., S. M. van der Pal, J. Bennebroek Gravenhorst, F. J. Walther, J. M. Wit, and K. M. van der Pal de Bruin. 2014. The effect of early catch-up growth on health and wellbeing in young adults. Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism 65(2-3):220–226.

van Veen, S., C. S. H. Aarnoudse-Moens, A. H. van Kaam, J. Oosterlaan, and A. G. van Wassenaer-Leemhuis. 2016. Consequences of correcting intelligence quotient for prematurity at age 5 years. The Journal of Pediatrics 173(June):90–95.

Vogindroukas, I., M. Stankova, E. N. Chelas, and A. Proedrou. 2022. Language and speech characteristics in autism. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment 18:2367–2377.

Wachman, E. M., and A. Lahav. 2011. The effects of noise on preterm infants in the NICU. Archives of Disease in Childhood-Fetal and Neonatal Edition 96(4):F305–F309.

Wehrle, F. M., A. Stöckli, V. Disselhoff, B. Schnider, S. Grunt, A.-L. Mouthon, B. Latal, C. F. Hagmann, and R. Everts. 2021. Effects of correcting for prematurity on executive function scores of children born very preterm at school age. The Journal of Pediatrics 238(November):145–152.e2.

Whitehouse, A. J. O., K. J. Varcin, S. Pillar, W. Billingham, G. A. Alvares, J. Barbaro, C. A. Bent, D. Blenkley, M. Boutrus, A. Chee, L. Chetcuti, A. Clark, E. Davidson, S. Dimov, C. Dissanayake, J. Doyle, M. Grant, C. C. Green, M. Harrap, T. Iacono, L. Matys, M. Maybery, D. F. Pope, M. Renton, C. Rowbottam, N. Sadka, L. Segal, V. Slonims, J. Smith, C. Taylor, S. Wakeling, M. W. Wan, J. Wray, M. N. Cooper, J. Green, and K. Hudry. 2021. Effect of preemptive intervention on developmental outcomes among infants showing early signs of autism: A randomized clinical trial of outcomes to diagnosis. JAMA Pediatrics 175(11):e213298.

WHO (World Health Organization). 2001. International classification of functioning, disability and health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

WHO. 2006. WHO Motor Development Study: Windows of achievement for six gross motor development milestones. Acta Paediatrica 95:86–95.

WHO. 2007. International classification of functioning, disability and health: Children & youth version. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

Williams, K., K. Patel, J. Stausmire, C. Bridges, M. Mathis, and J. Barkin. 2018. The neonatal intensive care unit: Environmental stressors and supports. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15(1):60.

Wilson-Ching, M., L. Pascoe, L. W. Doyle, and P. J. Anderson. 2014. Effects of correcting for prematurity on cognitive test scores in childhood. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health 50(3):182–188.

Zafeiriou, D. I. 2004. Primitive reflexes and postural reactions in the neurodevelopmental examination. Pediatric Neurology 31(1):1–8.

Zubler, J. M., L. D. Wiggins, M. M. Macias, T. M. Whitaker, J. S. Shaw, J. K. Squires, J. A. Pajek, R. B. Wolf, K. S. Slaughter, A. S. Broughton, K. L. Gerndt, B. J. Mlodoch, and P. H. Lipkin. 2022. Evidence-informed milestones for developmental surveillance tools. Pediatrics 149(3).