Advancing Vineyard Health: Insights and Innovations for Combating Grapevine Red Blotch and Leafroll Diseases (2025)

Chapter: 3 Current Knowledge on Grapevine Leafroll Disease

3

Current Knowledge on Grapevine Leafroll Disease

Among the viral diseases affecting grapevine, grapevine leafroll disease (GLD) is the most widespread, occurring wherever grapes are grown (Maree et al., 2013; Naidu et al., 2014), in all types of climates, and in all grapevine varieties. It is also considered the most economically important, with documented negative impacts on grape yield, juice and wine quality, and productive lifespan of affected vineyards (Almeida et al., 2013; Naidu et al., 2014, 2015; Alabi et al., 2016).

As discussed in a historical account by Maree et al. (2013), it is unclear exactly when GLD was first recognized as an infectious disease, although it likely originated in Europe, the Mediterranean basin, the Near East, or the Caucasus region, since these geographical regions are where grapevines were first domesticated (Dong et al., 2023). From there, the disease likely spread via human-mediated distribution of infected grapevine cuttings (Maree et al., 2013, and cited references), probably through vegetative cuttings collected during dormancy when grapevine is devoid of foliage and GLD symptoms are not apparent.

The deciphering of GLD etiology and biology was (and continues to be) a long and arduous process. Although it was recognized as a malady of grapevine since at least the 1800s, it was not until the 1930s that the graft-transmissible nature of GLD was documented (Scheu, 1935). In the 1970s, closterovirus-like virions were found in transmission electron microscopy studies of GLD-affected tissues (Namba et al., 1979; Faoro et al., 1981; Castellano et al., 1983), and in the 1980s scientists demonstrated the transmission of GLD by mealybugs (Engelbrecht and Kasdorf, 1990). The latter two developments strengthened the hypothesis that

GLD is a viral disease whose etiological agent(s) likely reside within the phloem tissues.

SYMPTOMS

Grapevine is a deciduous, woody perennial plant that goes through phases of vegetative growth, reproductive growth, and dormancy, with the timing and duration of each of these three phases varying across different regions and climates. All grapevine species can be classified broadly into two categories based on the color of the berry skin at maturity: red or black-fruited cultivars have reddish-purple berry skin that is conferred by the pigment anthocyanin, whereas white-fruited cultivars have green or golden berry skin (Walker et al., 2007). Vines affected by GLD contain detectable levels of grapevine leafroll-associated viruses (GLRaVs) throughout the year, but visual foliar GLD symptoms only begin to become apparent on affected vines around the middle of the reproductive growth phase that coincides with the onset of berry maturation or veraison (Naidu et al., 2014). The leaves remain symptomatic until they fall, following which the vine goes into dormancy. This pattern continues through each seasonal cycle for the lifespan of the infected grapevine, with symptoms absent during each subsequent vegetative growth stage and then re-emerging during veraison.

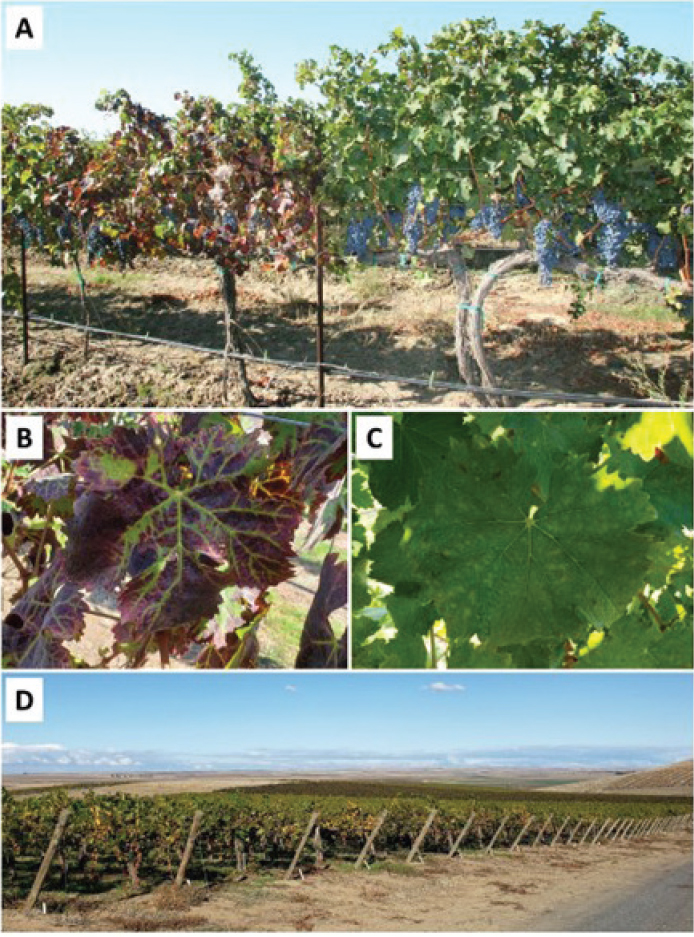

Foliar discoloration of grapevine leaves due to GLD is more apparent in red or black-fruited cultivars than in white-fruited cultivars (Naidu et al., 2014). In most red or black-fruited grapevine varieties, the classic foliar symptoms of GLD consist of red to purple coloration of the leaf areas between the veins, which typically develops first on the lower canopy mature leaves and then gradually expands to the upper canopy leaves, while uninfected vines of the same cultivar and age show no such coloration. The main veins on the discolored leaves remain green. GLD symptoms in white-fruited cultivars are much more subtle. In these grapevines, the interveinal areas of infected plants may become mildly chlorotic; however, this disease phenotype is not consistent across white-fruited cultivars and, even when present, may be confused with nutrient deficiency symptoms (see Figure 3-1). Hence, whereas classic GLD symptoms in red or black-fruited cultivars are relatively reliable signs of the likely occurrence of one or more of the GLRaVs in the vine, these symptoms may be less reliable for white-fruited cultivars. Other factors such as virus species and/or strain type, cultivar differences, and virus co-infections may also influence the expression of symptoms or lack thereof. In addition, stresses such as damage caused by mites and drought may mask foliar virus symptoms.

In advanced stages of the disease, mature leaves of GLD-affected grapevine typically display downward rolling of the leaf margins regardless of the

SOURCE: Naidu A. Rayapati, Washington State University and Olufemi J. Alabi, Texas A&M University.

berry color type (see Figure 3-2). Although the incubation period (i.e., time from infection to the first appearance) of the downward leafroll phenotype is not clear, the consistency of this symptom as an eventual outcome of infection by GLD-associated viruses likely informed its choice as the descriptor that typifies the disease. It is worth noting that grapevine red blotch virus (GRBV) may also induce leaf reddening in red or black-fruited grapevine cultivars, but in the case of grapevine red blotch disease (GRBD), the pattern of coloration is blotchy, the leaves do not show green vein banding, and the leaves do not display downward rolling in most cases. That said, there is significant overlap in symptoms of foliar coloration between GLD and GRBD (Adiputra et al., 2019); hence, visual observation of symptoms may be unreliable for their accurate diagnosis.

While the described leaf discoloration and leafroll symptoms are generally consistent for commonly grown V. vinifera grapevine cultivars, symptomatology is less consistent for other Vitis species. For instance, some non-vinifera grapevines with dark-colored berry skins such as juice grapes (e.g., V. labruscana ‘Concord’), muscadine grapes (M. rotundifolia), and rootstocks (e.g., V. riparia, V. rupestris, V. berlandieri, V. champini, and their hybrids) often remain symptomless throughout their growth phases even when infected with GLRaVs (Naidu et al., 2014). Some GLRaVs and/or their strains may also occur in V. vinifera vines as symptomless infections (Martelli et al., 2012; Poojari et al., 2013), and GLD symptomatology may differ between specific virus genotypes (Chooi et al., 2024). Given the complexity and inconsistency of GLD symptomatology, it is therefore important to be cautious when interpreting symptoms to inform diagnosis of the disease and its associated viruses.

IMPACT

Most of the documented impact of GLD comes from studies conducted using red or black-fruited V. vinifera cultivars, since their unique symptomatology lends itself to the proper selection of experimental vines to be used for such studies. Also, such studies have routinely been conducted with vines confirmed positive for grapevine leafroll-associated virus 3 (GLRaV-3), the most widely distributed of the GLD-associated viruses (Maree et al., 2013). Results from these studies show that GLD perturbates photosynthesis and carbohydrate metabolism in symptomatic leaves with significant reductions in both physiological parameters occurring during the post-veraison stage, which coincides with the expression of foliar GLD symptoms (Bertamini and Nedunchezhian, 2002; Sampol et al., 2003; Basso et al., 2010; Gutha et al., 2012; Moutinho-Pereira et al., 2012). GLRaV-3 can also affect the source/sink balance during the post-veraison stage of berry development by interfering with the berry maturation process via altering the

SOURCE: Olufemi J. Alabi, Texas A&M University.

expression of genes involved in the biosynthesis of anthocyanin and sugar metabolism (Vega et al., 2011). Enhanced expression of key genes involved in the biosynthesis of flavonols was detected in GLD symptomatic Merlot leaves, which also were found to accumulate anthocyanin compounds that should typically accrue predominantly in berry skins (Gutha et al., 2012). This probably explains the classic interveinal reddening symptoms that are displayed in red or black-fruited grapevine cultivars with GLD during the post-veraison stage.

Studies have also documented GLD-associated yield penalties, including reduction in berry cluster numbers and weights, uneven coloration of berries, reduced total soluble solid content of berries, and detrimental alterations to other fruit juice chemistry parameters (Cabaleiro et al., 1999; Borgo et al., 2003; Komar et al., 2007; Mannini et al., 2012; Alabi et al., 2016). GLD impacts on berry chemistry have been found to translate into negative impacts on various wine quality attributes (Mannini et al., 1998; Legorburu et al., 2009; Alabi et al., 2016) to such an extent that consumers could perceive GLD effects during sensory evaluations (Alabi et al., 2016). At the grower level, GLD can be detrimental to vineyard profitability. Annual average GLD-associated economic loss estimates derived from data from cv. Merlot vines in New Zealand (Nimmo-Bell, 2006), Cabernet Sauvignon vines in South Africa (Freeborough and Burger, 2008), and Cabernet franc vines in New York (Atallah et al., 2012) range from $972 ($1,322 in 2024 dollars1) to $2,117 ($2,880 in 2024 dollars) per hectare. GLD and its associated viruses also hinder the free, fast, and cost-effective exchange and movement of grapevine vegetative cuttings owing to the need to comply with phytosanitary regulations.

CAUSAL (OR ASSOCIATED) VIRUSES

Among viral plant diseases, GLD is unique in the complexity of its etiology. Most well-studied viral diseases in plants are caused by single virus species, although there are often many sequence variants or quasispecies of these viruses found in host plants (Domingo et al., 2006). By contrast, several distinct but taxonomically related virus species have been documented in GLD-affected grapevines, each of which may also have divergent strains and/or molecular variants. Collectively, viruses characterized from GLD-affected vines and linked to the disease are called grapevine leafroll-associated viruses (Martelli, 2000; Martelli et al., 2012). The word “associated” is contained in their species name because the classical set of rules guiding the decision to declare a pathogen as the causal agent of

___________________

1 Adjusted for inflation using the Consumer Price Index from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

a disease, known as Koch’s postulates (Loeffler, 1884; Brock, 1999; see Box 2-1 in Chapter 2), is yet to be completed for GLRaVs. To elucidate the etiological role of GLRaV-3 in GLD, Jarugula et al. (2018) developed complementary DNA (cDNA) clones of the virus and demonstrated its infectivity in Nicotiana benthamiana. More recently, Li et al. (2023) also reported the construction of an infectious GLRaV-3 clone which was successfully inoculated into virus-free grapevine plantlets via agro-infiltration (Shabanian et al., 2023) to reproduce GLD symptoms. If this report from Li et al. (2023) is independently validated by other investigators, Koch’s postulates would be fulfilled, confirming GLRaV-3 as a causal agent of GLD and opening up a wider discussion on a possible change to the names of GLRaVs.

Maree et al. (2013) provided a detailed historical account of the discovery of GLRaVs. The first two GLRaVs to be identified from symptomatic GLD-affected grapevine were determined to be morphologically similar but serologically distinct; these viruses were named GLRaV-1 (Gugerli et al., 1984) and GLRaV-2 (Zimmermann et al., 1990). Next to be discovered was GLRaV-3 (Zee et al., 1987), followed by subsequent reports of additional morphologically similar but serologically and/or molecularly distinct closteroviruses from GLD-affected vines which were sequentially named with number suffixes denoting their order of discovery. Various research groups reported the discovery of additional GLRaVs (Hu et al., 1990; Zimmermann et al., 1990; Walter and Zimmermann, 1991; Gugerli and Ramel, 1993; Choueiri et al., 1996; Gugerli et al., 1997; Alkowni et al., 2004; Maliogka et al., 2009; Abou Ghanem-Sabanadzovic et al., 2010), largely based on sequence-based taxonomic criteria such as the heat shock protein homology 70 (HSP70h) and the coat protein (CP) gene using thresholds specified by the Closteroviridae study group of the International Committee on the Taxonomy of Viruses.

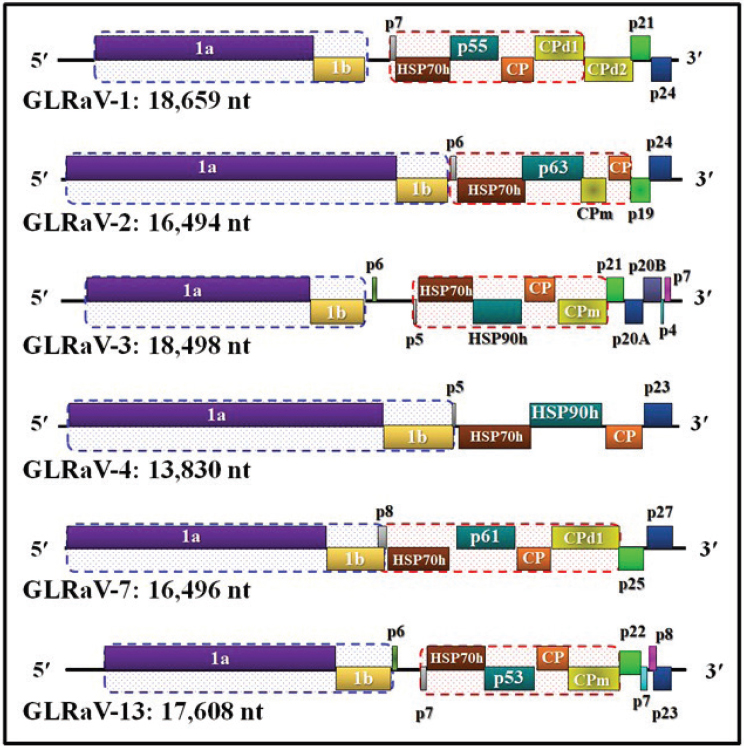

As complete genomes of GLRaVs became available, revealing common genome length and architecture among some viruses that had been previously designated as distinct species, the taxonomy of GLRaVs was revised to encompass not only their biological and serological properties, but also their genome characteristics (Martelli et al., 2012). This effort led to the current recognition of six distinct GLRaVs assigned into three genera in the family Closteroviridae (Martelli et al., 2012). These six viruses are grapevine leafroll-associated virus 1 (GLRaV-1; Ampelovirus univitis), grapevine leafroll-associated virus 2 (GLRaV-2; Closterovirus vitis), grapevine leafroll-associated virus 3 (GLRaV-3; Ampelovirus trivitis), grapevine leafroll-associated virus 4 (GLRaV-4; Ampelovirus tetravitis), grapevine leafroll-associated virus 7 (GLRaV-7; Velarivirus septemvitis), and grapevine leafroll-associated virus 13 (GLRaV-13; Ampelovirus tredecimvitis). GLRaV-1, GLRaV-3, GLRaV-4, and GLRaV-13 belong to the genus Ampelovirus, GLRaV-2 belongs to the genus Closterovirus, and GLRaV-7

is in the genus Velarivirus. More rigorous studies are warranted to better understand the role of GLRaV-7 variants in producing leafroll symptoms since the virus can be detected in both symptomatic and non-symptomatic vines and often in mixed infection with other viruses (Choueiri et al., 1996; Avgelis and Boscia, 2001; Reynard et al., 2015; Al Rwahnih et al., 2017). GLRaV-3 is the most prevalent of these viruses and is also considered the most economically damaging (Naidu et al., 2015); hence, GLRaV-3 is a primary focus of this report.

All GLRaVs are composed of monopartite, positive-sense, single-stranded, polycistronic RNA genomes, but they differ in their genome lengths and in the number and arrangements of their encoded genes (see Figure 3-3). Although there is some variation between studies and isolates, in general, GLRaV-1 and GLRaV-3 have been shown to have the largest genomes, GLRaV-4 strains have the smallest genomes, and the rest have intermediate genome sizes. The size variations among Closteroviridae viruses result from various modification events during viral replication such as sequence deletion, sequence acquisition from other sources, genome bipartition, and gene duplication (Martelli et al., 2012).

The genome size differences are also reflected in the number of open reading frames (ORFs) that are encoded by the GLRaVs. However, regardless of their genome size differences and the number of ORFs, GLRaVs carry two main conserved gene block segments across the species. These are the replication gene block (RGB), which contains two N-terminal ORFs that function in genome replication, and the quintuple gene block (QGB), which contains a set of five genes of varied functions toward the C-terminus. Only GLRaV-4 lacks the QGB. Apart from these conserved genes, some GLRaVs encode additional genes toward their C-terminus; some of these have known functions while others are putative genes. The evolutionary basis for such genome complexity is not well understood and could be further elucidated through future research.

Given that GLRaV-3 was a main focus of this study, a query of the National Center for Biotechnology Information GenBank database was conducted to examine the GLRaV-3 genome in greater detail. This search returned 81 hits for complete GLRaV-3 genomes, which ranged in length from 17,919 to 18,785 nucleotides as of August 8, 2024. Notably, the 5′ and 3′ extremities have only been experimentally verified for a few of these GLRaV-3 isolates via random amplification of complementary DNA ends (RACE) assays. Each of these genomes contain 12 ORFs and some GLRaV-3 isolates may also encode an additional ORF2 (p6) proximal to the RGB and before the QGB. The GLRaV-3 ORFs are numerically named with the RGB ORFs designated as 1a and 1b, a non-conserved ORF2, the QGB ORFs 3-7, and the ORFs 8-12. In analogy with monopartite closteroviruses, ORFs 1a and 1b of GLRaV-3 function in replication, ORF2 has

NOTE: Details of the functions of the encoded genes can be gleaned from Naidu et al. (2015) and Song et al. (2021).

SOURCE: Olufemi J. Alabi, Texas A&M University.

unknown functions, ORF3 encodes a small transmembrane protein and may function in cell-to-cell movement, ORF4 encodes the HSP70 likely serving as a molecular chaperone for plasmodesmata targeting and cell-to-cell movement, ORF5 (p55) has unknown functions, ORF6 encodes the CP for virion encapsidation, and ORF7 encodes the minor capsid protein (CPm) that may be a component of the virion tail (Agranovsky et al., 1995; Satyanarayana et al., 2004; Naidu et al., 2015). The functions of ORFs 8-12 are not clearly understood, although recent studies have shown that ORFs 8-10 could function as RNA silencing suppressors to counteract the grapevine RNA interference (RNAi) defense (Reed et al., 2003; Lu et al., 2004; Chiba et al., 2006).

VECTORS

Propagation of infected planting material is the primary mechanism for GLD spread, and spatial patterns suggest that the disease typically emanates from a focal point source of insect infestation (Cabaleiro and Segura, 1997; Cabaleiro et al., 2008; Arnold et al., 2017). Vectors of GLRaVs are classified in the order Hemiptera and fall into the superfamily Coccoidea, comprising approximately 8,000 species. Within this superfamily, mealybugs (family Pseudococcidae) and soft scales (family Coccidae) are demonstrated vectors for GLRaVs (Tsai et al., 2010; Le Maguet et al., 2012; Blaisdell et al., 2015; Herrbach et al., 2017). GLRaV-3 transmission by a mealybug, Planococcus ficus Signoret, was first documented in 1980 (Engelbrecht and Kasdorf, 1990), followed by reports of transmission by additional mealybug and soft-scale species (Belli et al., 1994; Cabaleiro and Segura, 1997). Almeida et al. (2013) reported that among some of the primary wine grape growing regions of the world, Pl. ficus and Pseudococcus calceolariae Maskell appear to be the most important vectors but noted that all mealybugs and soft scales that feed on wine grapes should be viewed as potential vectors. Insects considered capable of transmitting GLRaVs essentially encompass all common mealybugs and soft scales found worldwide in regions where GLD is present. In addition to Pl. ficus and Ps. calceolariae, these include the mealybugs Pseudococcus maritimus Ehrhorn (grape mealybug), Pseudococcus viburni Signoret (obscure mealybug), Pseudococcus longispinus Targioni-Tozzetti (longtailed mealybug), Ferrisia gilli Gullan (Gill’s mealybug) (Jones and Nita, 2020), Pseudococcus comstocki Kuwana (Comstock mealybug), Planococcus citri Risso (citrus mealybug), Phenacoccus aceris Signoret (apple mealybug), and Heliococcus bohemicus Sulc (bohemian mealybug) (as reviewed in Daane et al., 2012; Herrbach et al., 2013), as well as soft scales such as Pulvinaria vitis L. (woolly vine scale), Parthenolecanium corni Bouché (European fruit lecanium scale), Ceroplastes rusci L. (fig wax scale), Neopulvinaria

innumerabilis Rathvon (cottony maple scale), Coccus longulus Douglas (long brown scale), Parasaissetia nigra Nietner (black scale), and Saissetia sp. (Belli et al., 1994; Mahfoudhi et al., 2009; Le Maguet, 2012; Herrbach et al., 2013; Krüger and Douglas, 2013).

GLRaV-3 is the primary virus that causes GLD in the United States. However, multiple viruses causing GLD can coexist and can be transmitted by the same insect vector. There is no indication of strict vector-virus species specificity in transmission (Tsai et al., 2010). Pl. ficus can transmit at least five different GLRaVs, although transmission efficiency varies. To date, all tested grape-associated mealybug species can transmit various GLRaV species (Tsai et al., 2010; Le Maguet et al., 2012). Thus, all mealybugs inhabiting grapevines are presumed to be GLRaV vectors unless proven otherwise. Fewer studies have investigated GLRaV transmission by soft scales, as compared with mealybugs (Bahder et al., 2013), but two, Pu. vitis and Pa. corni, are known to be competent (Hommay et al., 2009; Bahder et al., 2013). The grape mealybug, Ps. maritimus, and Pa. corni are both competent vectors of GLRaV-3 with established populations in North American vineyards (Bahder et al., 2013). Although vector efficiency differs between these, Bahder et al. (2013) demonstrated that multidirectional transmission could occur between Vitis species by both insects (interspecific transmission).

Four mealybug species are commonly found in California vineyards: Pl. ficus, Ps. longispinus, Ps. maritimus, and Ps. viburni. The vine mealybug, Pl. ficus, causes the most damage to wine and table grapes. It is distributed throughout many wine grape growing regions of the world, occurring in more than 47 countries (Ji et al., 2020). The insect’s native range is not clear, although Israel is postulated as the origin of populations in North and South America, Europe, and South Africa (Daane et al., 2018). There have been few studies of host plant preference and suitability for mealybug species associated with grapes in California. Although grapevines are a preferred host for Pl. ficus, the species is polyphagous and invades host plant species in more than 31 genera from 25 families (Almeida et al., 2013; García Morales et al., 2016). In addition to causing damage to grapes, Pl. ficus also affects weedy and agricultural plants such as fig, quince, mangos, tomatoes, beets, and avocados. Recently, Correa et al. (2023) revisited the taxonomy of previously synonymized as Pl. ficus specimens from different regions of the world and delineated them into two species: Pl. ficus (Signoret) s.str. and Pl. vitis (Niedielski) based on morphological and molecular analyses. The specimens from the Eastern Mediterranean and California were reclassified as Pl. vitis (Niedielski).

Nymph and adult mealybugs feed on the phloem sap from all parts of host plants, including the roots, leaves, fruits, and trunks. To extract sap, the insects insert a needle-like feeding structure called a stylet into plant vascular tissues. If the grapevine is infected with GLRaV, the virus particles are

ingested along with the sap during this process. During feeding, mealybugs excrete honeydew that is high in carbohydrates. As honeydew is flicked away from the insect, it accumulates on the surrounding leaves and plant, where it serves as a substrate for the growth of sooty mold, which reduces host photosynthesis. Accumulation of high concentrations of sooty mold causes cosmetic damage that reduces fruit marketability and may form a hard waxy layer on the infested plant. Extensive infestations of grapevine mealybug can lead to premature leaf shedding and the gradual weakening of vines when infestations occur in consecutive years. Over time, excessive feeding damage can cause defoliation and vine death. Certain mealybug species, including Ps. calceolariae and Pl. ficus, often establish a segment of their population on vine roots (Walton and Pringle, 2004; Bell et al., 2009), and these insects can dwell underground. In California, root colonization appears to be limited to regions with sandy soils and/or extreme heat and climate change could influence the geographical range and ecology of this vector (Ji et al., 2020). This situation poses a significant challenge during replanting because even after the vine is removed, residual roots can remain viable for extended periods, providing sustenance for GLRaVs and mealybugs, thereby acting as a conduit from the previously infested vineyard to the new replanted vines (Pietersen, 2006).

Mealybugs are the primary vectors of GLRaVs in California wine grape production systems. Diverse mealybugs are known pests of wine grapes in California, and based on current studies, the transmission of these viruses appears to be somewhat non-specific. Mealybugs present in California and shown to transmit various GLRaVs using local virus isolates and insect populations include Pl. ficus, Ps. longispinus, Pl. citri, Ps. viburni, Ps. maritimus, and F. gilli (Golino et al., 2002; Tsai et al., 2010; Wistrom et al., 2016). Due to the reproductive capacity and the generation time (number of generations per year) of Pl. ficus, it is the primary vector of concern in most wine grape production areas of California (Daane, 2024). Other species of concern in North Coast and San Joaquin Valley vineyards are the grape and obscure mealybugs; in Central Coast vineyards, obscure and longtailed mealybugs can cause damage, and longtailed mealybugs may also occur in the Coachella Valley. Soft scale insects are present as pests in California vineyards, but thus far, no transmission assays have been reported for grapevine scale insects collected from California. In Washington State, Bahder et al. (2013) demonstrated that European fruit lecanium scale, Pa. corni, could transmit GLRaV-3 with low efficiency.

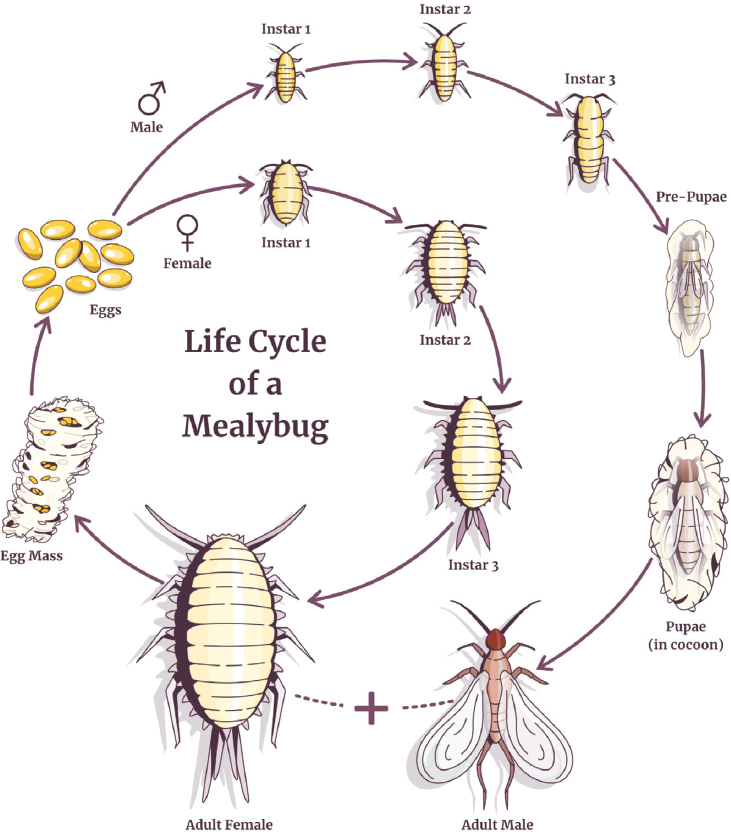

Table 3-1 summarizes key features of known mealybug GLRaV vectors in California. The mealybug life cycle (see Figure 3-4) is sexually dimorphic, and features of the insects’ reproduction and ecology vary depending on the environment. Some mealybug vectors of GLRaVs produce eggs that are deposited and hatch later (information about number

of generations is provided in Table 3-1), while others produce eggs that develop in the female and hatch within or immediately after release. Females can be highly fecund, producing 100-200 eggs in a 10-12-day period. Female mealybugs have 2-3 larval instars, with the first instar nymph referred to as the crawler phase. Male mealybugs have 3-4 larval instars and then a prepupal or cocoon stage pupal stage. The newly hatched mealybug nymphs (crawlers) are the most mobile developmental stage and considered to be the most important in transmission and spread

TABLE 3-1 Vectors of GLRaVs in California

| Common Name | Scientific Name | Regions of Importance/Distribution | Life Cycle | Oviposition | Virus Transmission (Virus Species) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grape mealybug | Pseudococcus maritimus | North Coast, San Joaquin Valley, Central Coast (Monterey and Santa Cruz counties), foothills of the Sierra Nevada | Two generations each year; overwinters as an egg or crawler under loose bark, in cordons, or along upper portions of the vine trunk | Eggs deposited within an egg sac | GLRaV-3 | Golino et al. (2002); Bahder et al. (2013) |

| Obscure mealybug | Pseudococcus viburni | North Coast, San Joaquin Valley, Central Coast | Multiple overlapping generations with no diapause over the winter; all life stages present on vines year-round; may overwinter under bark of the trunk, cordons, and spurs | Eggs deposited within an egg sac | GLRaV-3, GLRaV-5a | Golino et al. (2002) |

| Longtailed mealybug | Pseudococcus longispinus | Central Coast, Coachella Valley | Multiple overlapping generations with no diapause over the winter; all life stages present on vines year-round | Give birth to live crawlers | GLRaV-3, GLRaV-5,a GLRaV-9a | Cabaleiro and Segura (1997); Golino et al. (2002); Tsai et al. (2010) |

| Vine mealybug | Planococcus ficus | Established in at least 17 California counties across Coachella Valley, San Joaquin Valley, foothills of the Sierra Nevada, Central Coast, North Coast | More sensitive to cold temperatures than grape mealybug; 2-3 generations per year in coastal regions and 5-7 in warmer regions (e.g., lower San Joaquin Valley); no diapause during the winter; all or most life stages present on vines year-round depending on region | Eggs deposited within an egg sac | GLRaV-1, GLRaV-3, GLRaV-4, GLRaV-5,a GLRaV-9a | Golino et al. (2002); Tsai et al. (2008); Petersen and Charles (1997) |

| Citrus mealybug | Planococcus citri | Widespread distribution in California, except North Coast; polyphagous | Capable of multiple generations depending on temperature; at least 4-5 overlapping generations per year in California; overwinter as eggs; all or most life stages usually present | Eggs deposited within an egg sac | GLRaV-3, GLRaV-5a | Cabaleiro and Segura (1997); Cocco et al. (2018); Golino et al. (2002) |

| Gill’s mealybug | Ferrisia gilli | Recently established on grapes in El Dorado county; present in Lake county; found on pistachios in the Southern San Joaquin Valley but not known to be widespread on grapes in other areas of the state | Two to three generations per year; overwinter as nymphs under bark, in crevices, and several inches below the soil line (not observed to feed when overwintering) | Give birth to live crawlers | GLRaV-3 | Wistrom et al. (2016); Jones and Nita (2020); Gullan et al. (2003); UCCE (n.d.); Haviland et al. (2006) |

| European fruit lecanium scale | Parthenolecanium corni | Found to be a vector in Washington State; present in California | Develop through three life stages (egg, nymph, and adult); produce one generation per year | Eggs produced under adult female body | GLRaV-1, GLRaV-3 | Martelli (2000); Hommay et al. (2009); Bahder et al. (2013) |

| Cottony maple scale | Neopulvinaria innumerabilis | Present in California | Develop through three life stages (egg, nymph and adult); produce one generation per year | Eggs produced under adult female body | GLRaV-1, GLRaV-3 | Martelli (2000); Zorloni and Prati (2006) |

a GLRaV-5 and GLRaV-9 have been reclassified as GLRaV-4 strains (Adiputra et al., 2019).

of GLRaVs. The female insects become less mobile as they mature. Mature male mealybugs are small in size and have wings, but they are rarely seen and do not feed on plants because their mouthparts are not functional. Factors such as the number of generations produced per year and the length of time during which the insects are active vary depending on environmental conditions and species-specific differences; all life stages may be present throughout the year for most mealybug species.

PATHOGEN-VECTOR INTERACTIONS

The characteristics of GLRaV transmission based on timing of acquisition, latent period, and inoculation are consistent with a semi-persistent mode of transmission (Tsai et al., 2008), which is generally characterized by acquisition periods of hours to days and similar timing for inoculation (reviewed in Ng and Falk, 2006). Acquisition and inoculation of semipersistent viruses involves phloem feeding, which takes time as most hemipterans must feed for 30 minutes to several hours to reach the phloem tissue (Moreno et al., 2012). GLRaVs have been presumed to be transmitted in a semi-persistent manner because of their classification in the family Closteroviridae. All viruses in this family that have been thoroughly characterized for virus transmission characteristics show clear signatures of semi-persistent transmission with regard to timing and virus retention sites in the vectors. For example, the whitefly-borne criniviruses and aphid-borne closteroviruses are transmitted semi-persistently and bind to the insect foregut (classified as externally borne) (Costa and Grant, 1951; Raccah et al., 1976; Tian et al., 1999; Chen et al., 2011; Killiny et al., 2016). For GLRaVs, the localization of viral particles within the vector is not yet clear but transmission characteristics are consistent with a non-circulative, externally borne virus. GLRaV virus particles appear to bind to the insect exoskeleton but not traverse membrane barriers or replicate, a feature they share with known non-persistent and semi-persistent transmitted viruses. As insects ingest phloem sap from plants infected with GLRaV-3, virus particles are retained in the foregut up to four days, after which insects molt and GLRaV-3 and infectivity are lost (Tsai et al., 2008). It is hypothesized that virus particles are shed along with the exoskeleton during insect molts; thus, GLRaVs are not transstadially passaged, and insects are thought to lose infectivity after a molt.

Transmission of GLRaV-3 takes place within a 1-hour acquisition access period (AAP) and a subsequent 1-hour inoculation access period (IAP), with apparently no latency period between virus acquisition and transmission (Tsai et al., 2008). However, a study conducted in South Africa by Krüger et al. (2015) determined that an AAP and IAP of 15 minutes each was sufficient for Pl. ficus to acquire and transmit GLRaV-3. The

differences observed between these studies may be attributed to differences in GLRaV-3 isolates, their titers in source plants, the sensitivity of virus detection methods, and non-uniform experimental conditions. Although all grape-associated mealybug species appear to be competent vectors of GLRaV species in laboratory assays, transmission efficiency varies across vector species (Blaisdell et al., 2015; Wistrom et al., 2016). Transmission efficiency increases with the amount of time spent feeding, up to 24 hours, with efficiency peaking at around 10 percent daily per individual under controlled laboratory conditions for Pl. ficus (Tsai et al., 2008). Prator and Almedia (2020) observed two virus-binding sites for GLRaV-3, the stylet and the cibarium (the space in front of the true mouth cavity in which the food of an insect is chewed), in mouthparts of Pl. ficus insects fed on purified virus solutions and infected plant cuttings. Overall, the transmission efficiency in these experiments was low, ranging from 0.5 percent to 12.7 percent and the number of insect stylets and cibaria that exhibited detectable virus was also low, ranging from 2.7 percent to 4.8 percent depending on the source of the virus.

Vector species with a greater number of generations per year or higher fecundity levels present a more significant transmission risk. It is possible to find all life stages of Pl. ficus year-round on grapevines. The vine mealybug exhibits 4-7 generations annually, depending on temperature and geographic location. In coastal California vineyards, there are roughly one, two, three, and four annual generations of Pa. corni, Ps. maritimus, Ps. viburni, and Pl. ficus, respectively (Geiger and Daane, 2001; Gutierrez et al., 2008; Varela et al., 2013). All life stages of mealybugs and soft scales may have the capacity to transmit GLRaV-3, but nymphs are more proficient (Petersen and Charles, 1997; Tsai et al., 2008). Early instar nymphs are the primary dispersal stage because they are more active than adults. In addition, females and nymphs are primarily responsible for virus transmission because adult males do not feed. The spread of GLRaV transmission occurs over short distances corresponding to the movement pattern of vector insects. Females and immature instars, which lack wings, must crawl between hosts to colonize and inoculate new plants. Long-distance spread is likely associated with physical movement of insects via wind, clothing, or farm equipment (Haviland et al., 2005; Tsai et al., 2010; Daane et al., 2012; Almeida et al., 2013).

Virus-encoded functions responsible for the vector transmission have not yet been assigned or mapped to specific genes or ORFs in GLRaV-3, possibly due to challenges associated with such experiments. However, the same genes involved in systemic spread of closteroviruses may be involved in vector transmission, similar to the crinivirus or potyvirus transmission (Torrance et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2011). For instance, the CPm protein was demonstrated to be involved in whitefly transmission

of lettuce infectious yellows virus, a bipartite crinivirus, binding specific receptors in the foregut of the insect and facilitating virion retention (Chen et al., 2011; Ng et al., 2021). A connection between vector specificity of closterovirids and amino acid sequences of the most conserved protein motifs, i.e., RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRP), helicase, and HSP70, was revealed in phylogenetic analyses that produced separate lineages of viruses transmitted by aphids (genus Closterovirus), whiteflies (Crinivirus), and mealybugs and scales (Ampelovirus) (see Karasev, 2000). While not implying a direct involvement of these conserved domains in insect transmission, this phylogenetic distinction suggests a powerful effect of the vector shaping closterovirus evolution, more powerful than a host plant influence (Karasev, 2000).

HOST-PATHOGEN INTERACTIONS AND HOST DEFENSE MECHANISMS

Just like other closterovirids, GLRaV-3 and other GLRaVs display clear tissue tropism and are phloem-limited in infected plants (Lesemann, 1988; Ng and Zhou, 2015). In early electron microscopy studies, closteroviruses were found to induce characteristic membrane vesicles in infected cells and this feature was even considered a diagnostic mark of closteroviruses at the dawn of virus taxonomy (Esau, 1960; Esau and Hoefert, 1971; Lesemann, 1988). This association with the phloem leads to symptoms induced by closteroviruses that often affect phloem tissue, veins, cambium, and resemble nutritional deficiencies, and it may also be responsible for the low concentration of the viruses in infected plants, one factor that makes closterovirus detection challenging (Lesemann, 1988; Wisler et al., 1998; Sun and Folimonova, 2022).

In the infected plant, GLRaV-3 induces multiple 3′ co-terminal subgenomic RNAs (sgRNAs) (Hu et al., 1990; Rezaian et al., 1991; Saldarelli et al., 1994; Ling et al., 1998), which are believed to be translated into the proteins encoded by the ORFs downstream of the replication-associated ORFs 1a and 1b (Ling et al., 2004; Jarugula et al., 2010, 2018; Maree et al., 2010). Assignments of the functional activity for the GLRaV-3-encoded proteins (Ling et al., 1998, 2004; Burger et al., 2017) are largely based on conserved protein motifs and comparisons to other closterovirus model systems, such as beet yellows virus (BYV) and citrus tristeza virus (CTV), where genetic systems based on infectious cDNA clones were better developed and functions of many virus-encoded protein products were established experimentally (see Dolja et al., 2006; Folimonova, 2020).

Replication-associated functions have been assigned to the protein products encoded by ORFs 1a and 1b with easily identifiable conserved domains of RdRP, helicase, and methyltransferase; the ORF 1a product

also contains a leader papain-like protease (L-Pro) domain close to its N-terminus (Ling et al., 2004). This same ORF 1a-encoded protein also contains an AlkB conserved domain, located between methyltransferase and helicase domains; it is often found in viruses infecting woody plants and is implicated in RNA demethylation related to the RNA damage repair (Maree et al., 2008; van den Born et al., 2008). L-Pro domain encoded by ORF 1a has been implicated in RNA accumulation, virus invasiveness, and systemic spread in BYV and CTV (Dolja et al., 2006; Kang et al., 2018) and in superinfection exclusion in CTV (Atallah et al., 2016).

The functional activity for p6, downstream of ORF 1b, has not been established or assigned, and its expression in infected plants is uncertain (Maree et al., 2015). The p5 ORF encodes a small hydrophobic protein similar to an analogous protein expressed by BYV and shown to target endoplasmic reticulum membrane, facilitating cell-to-cell movement of BYV (Peremyslov et al., 2004a). The HSP70 homolog protein, together with the downstream p55 protein, is involved in cell-to-cell movement and virion assembly, forming a peculiar “tail” structure including also the major CP and CPm (Agranovsky et al., 1995; Tian et al., 1999; Alzhanova et al., 2000, 2001; Satyanarayana et al., 2000, 2004; Peremyslov et al., 2004b).

GLRaV-3 genetic variability studies have typically been conducted using partial sequences of a few taxonomically informative genes such as RdRP, HSP70h, and CP (Maree et al., 2013, and cited references), although a few more recent studies have addressed the same topic using complete or nearly complete viral genomes (Diaz-Lara et al., 2018). Together, these studies have revealed that GLRaV-3 comprises a complex of genetic variants in several phylogenetic groups which may diverge from each other by as much as 30 percent in the whole genome nucleotide sequence (Thompson et al., 2019). To date, researchers have identified eight distinct phylogroups of the virus across different geographical regions based on complete CP and genome-length sequences of GLRaV-3 (Maree et al., 2013; Diaz-Lara et al., 2018; Thompson et al., 2019), designated with Roman numerals as groups I, II, III, V, VI, VII, IX, and X. Apart from the identified phylogroups, a few GLRaV-3 isolates appear to be divergent in that they do not cluster into any of the identified clades (Diaz-Lara et al., 2018; Thompson et al., 2019).

The tremendous genetic diversity of GLRaV-3 leads to potential challenges in virus detection and diagnosis, and GLD management strategies. Diaz-Lara et al. (2018) identified only a short area in the 3′-terminal, untranslated region of the GLRaV-3 genome suitable as a “universal” target for detection of all genetic variants of GLRaV-3 by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). Genetic diversity assessments conducted for other major GLRaVs, including GLRaV-1 (Alabi et al., 2011; Fan et al., 2015; Donda et al., 2017), GLRaV-2 (Jarugula et al., 2010), and GLRaV-4 (Rubio et al., 2013; Adiputra et al., 2019), have revealed that

grapevines harbor complex populations of genetic variants of GLRaVs due to multiple factors, which are extensively discussed in Naidu et al. (2015). It is also important to recognize that virus isolates included in genetic diversity studies of the different GLRaVs mainly emanated from V. vinifera vines; as a result, the extent of the complexity of natural populations of GLRaVs may be underestimated. Although the biological significance of such genetic variability is poorly understood, it may have implications for accurate and reliable diagnosis in clean plant programs.

DIAGNOSTICS

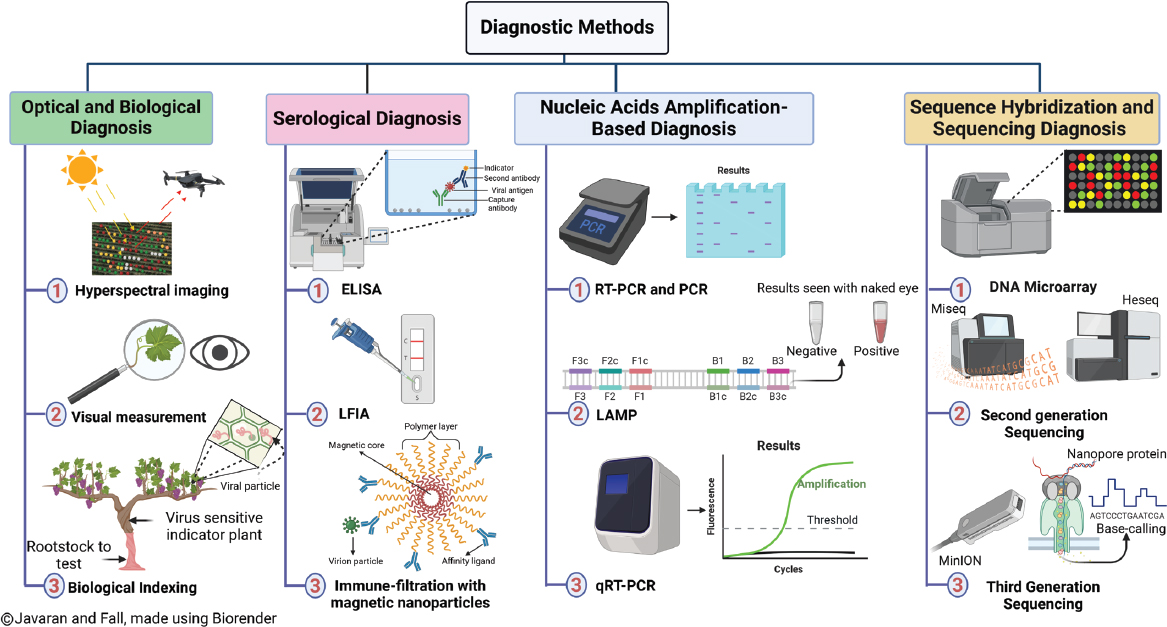

Given the negative impacts of GLD, it is imperative to conduct regular monitoring to identify grapevines affected by the disease. Tools for early and accurate identification of GLD and its associated viruses enable critical disease control measures such as removing affected vines, controlling vectors and the movement of agricultural machinery, treating instruments, and replanting with certified vines (Fuchs, 2020; Javaran et al., 2023a). This section examines the diverse diagnostic methods employed for detecting GLD with a particular focus on GLRaV-3 (see Figure 3-5), since it is understood to be the most prevalent and most economically damaging virus. However, it is important to recognize that various technical protocols for virus detection may be more or less sensitive to the genetic diversity of the GLRaVs beyond GLRaV-3, which needs to be taken into account when utilizing these methods to inform management strategies.

Detection of GLD by Optical-Based Diagnostic Methods

Visual inspection of grapevines has historically been a mainstay of GLD detection. Recently, hyperspectral imaging has emerged as a cutting-edge technology to enhance optical-based diagnosis and facilitate early detection (MacDonald et al., 2016; Mahlein, 2016; Galvan et al., 2023). This technology uses spectral sensors to capture the electromagnetic spectrum reflected by plants, allowing for the identification of distinct spectral patterns associated with infected and non-infected leaves. While hyperspectral imaging shows promise in monitoring the dynamic development of symptoms (Bendel et al., 2020), it is still in the early stages of validation and remains sensitive to environmental factors, such as daylight intensity. Although this technology has demonstrated effectiveness in detecting GLD symptoms in both red or black- and white-fruited cultivars, further validation is needed to establish its reliability as a practical diagnostic tool (Naidu et al., 2009; MacDonald et al., 2016; Sinha et al., 2019; Bendel et al., 2020; Gao et al., 2020; Junges et al., 2020; Galvan et al., 2023). Recent studies indicate that asymptomatic GLRaV-3-infected vines exhibit the most distinctive

SOURCE: Mamadou L. Fall, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada.

spectral differences, enabling reliable differentiation of non-infected vines and symptomatic vines (Galvan et al., 2023), highlighting the potential of this method to detect early-stage infection.

Detection of GLRaVs by Biological Indexing

Biological indexing involves the use of sensitive indicator plants to detect viruses in infected plants. While the use of this diagnostic method has declined in recent years in favor of molecular and serological methods, it still holds value for studying newly discovered viruses for which nucleotide sequences and antibodies are unavailable, precluding their molecular and serological identification, respectively (Zherdev et al., 2018). Biological indexing is also invaluable for studying the etiology and biology of newly detected viruses. There are two distinct approaches to detect grapevine viruses using indicator plants: sap inoculation and bud grafting. Sap inoculation, which involves the use of the sap and juice from infected plants, is suitable for detecting mechanically transmissible viruses. Compared with woody plants like grapevine, virus detection with this method can be accomplished more rapidly when using herbaceous indicator plants like Chenopodium quinoa, Chenopodium amaranticolor, Cucumis sativus, and Nicotiana species (Javaran et al., 2023b). Because GLRaV-3 is not transmitted by mechanical equipment or pruning, sap inoculation is not suitable for its detection. Bud grafting is a biological indexing procedure that is used to detect graft-transmissible viruses like GLRaV-3, but it is a very time-consuming technique. Common grapevine varieties used as indicators include V. vinifera cvs. Barbera, Cabernet franc, Cabernet Sauvignon, Gamay, Mission, and Pinot noir (Rowhani et al., 2017). Using conventional methods, bud grafting may take anywhere from 16 months to three years to complete. Alternatively, a time-efficient in vitro biological indexing method has been developed, which takes only 4-12 weeks from grafting to the expression of symptoms (Cui et al., 2015; Hao et al., 2021). While biological indexing can indicate the involvement of an infectious agent in the tested material, the technique is insufficient for specific detection of viruses involved in the GLD complex due to their overlapping symptomatology.

Detection of GLRaVs by Serological Methods

Serological diagnostic techniques such as enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), lateral flow immunoassay, direct immune-printing, immune-filtration with magnetic nanoparticles, dot-immunobinding assay, immunocapture RT-PCR, and immunosorbent electron microscopy rely on the interaction between monoclonal and/or polyclonal antibodies and

viral particles. Several companies have developed commercial detection kits for GLRaV-3 and 17 other grapevine viruses (Blouin et al., 2017). While serological diagnostic methods offer speed and simplicity, they also have limitations, including a risk of generating false-negative results. These limitations stem from factors such as the type of biomaterial, antibody quality, sensitivity, specificity, and grapevine tissue- and cultivar-specific influences. To address these limitations, recent advancements include the development of lab-on-a-chip methods designed to enhance the effectiveness of serological tests. Lab-on-a-chip methods, also known as microfluidic chips or microfluidic devices, consolidate multiple laboratory functions onto a single microchip-sized platform. This technology has recently demonstrated remarkable effectiveness in the detection of GLRaV-3, often providing results within minutes (Buja et al., 2022).

Detection of GLRaVs by Nucleic Acid Amplification-Based Methods

With the introduction and decreasing cost of PCR, many diagnostic approaches have transitioned from biological indexing and serological methods to nucleic acid amplification-based methods. These include standard PCR, RT-PCR, real-time or quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR), multiplex PCR, and nested PCR (Zherdev et al., 2018). Various grapevine viruses, including GLRaV-3, GLRaV-1, and GRBV, have been successfully detected using nucleic acid amplification-based methods (Gambino, 2015; Diaz-Lara et al., 2018; DeShields and Achala, 2023). PCR-based methods offer numerous advantages, such as high sensitivity, specificity, and time efficiency. However, they do have some limitations. False results can occur due to contamination in reactions, faulty primer designs, nuclease degradation of RNA or DNA template, and occasionally, they can be affected by grapevine phenolic compounds and polysaccharides if carried over to the nucleic acid template.

Another rapid detection option that is suitable for vineyard conditions involves on-site amplification of specific DNA sequences using a set of primers through loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP). By adding the reverse transcriptase enzyme to the reaction tube, the reverse transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification assay has been used to detect GLRaV-3 (Walsh and Pietersen, 2013), as well as other grapevine viruses in vineyards. This optical detection method offers several advantages, including its high speed, high specificity, resistance to inhibitors, ease of use, and the absence of the need for a thermal cycler (Zherdev et al., 2018).

Detection of GLRaVs by DNA Microarray Methods

DNA microarray diagnostic methods are based on the principle of DNA strand hybridization. Specific DNA probes, which are based on the

genomes of grapevine viruses, are attached to a solid plate. Subsequently, cDNAs from infected samples are fluorescently labeled. These labeled target sequences then bind covalently to the DNA probes, facilitating the detection of viruses. This technology allows for the simultaneous detection of multiple viral pathogens and offers sensitivity levels that fall between those of ELISA and qRT-PCR (Boonham et al., 2003). A diagnostic oligonucleotide microarray was developed for the simultaneous detection of GLRaV-3 and other grapevine viruses (Engel et al., 2010). Through two different cDNA amplification and non-amplification methodologies, this microarray successfully identified 15 and 33 grapevine viruses, respectively. The versatility of the DNA microarray method is evident in its capacity to identify new viruses through partial attachment of target sequences to the probes. Additionally, a modified chip containing 1,578 specific viral and 19 internal probes has been developed for the detection of 38 different plant viruses, making it suitable for co-infected samples (Zherdev et al., 2018).

Detection of GLRaVs by Second-Generation Sequencing (Short Read Sequencing)

High-throughput sequencing (HTS) has revolutionized the ability to swiftly and comprehensively investigate plant viromes. Unlike nucleic acid amplification-based and serological diagnostic methods, HTS offers the capability to not only detect known viruses but also identify novel ones. HTS has facilitated the detection of many known grapevine viruses and led to the identification of new ones including GRBV, grapevine Pinot gris virus, and grapevine Roditis leaf discoloration-associated virus (Zhang et al., 2011; Marais et al., 2018; Zherdev et al., 2018; Fall et al., 2020). However, despite its remarkable capabilities, HTS also has some limitations. One drawback is related to the type of nucleic acid extraction method used. For instance, viral sequences are typically present in low abundance within the total nucleic acid extract, which can limit the detection sensitivity of low-titer viruses unless target enrichment steps are included during preparation of the cDNA libraries. Furthermore, unlike bacterial and fungal metagenomics, there are no universal gene markers for amplicon sequencing of viral genomes. To overcome these challenges, various purification methods have been developed to enrich virion-associated nucleic acids, viral small interfering RNA, polyadenylated RNA, and double-stranded RNA (dsRNA). Another limiting factor is that HTS is generally more costly than other diagnostic methods as it requires high-tech and expensive sequencing equipment, as well as substantial investments in bioinformatics for data analysis. To address these challenges, various solutions have been proposed, including multiplex barcoding to minimize analytical costs, the development of user-friendly and straightforward pipelines for virus diagnosis

and diversity analysis, and the exploration of single-molecule sequencing without the need for amplification.

Detection of GLRaVs by Third-Generation Sequencing (Long Read Sequencing)

Third-generation sequencing technologies such as single-molecule real-time sequencing and nanopore sequencing technology may overcome some of the limitations of second-generation sequencing. For example, the MinION, a compact, portable sequencer developed by Oxford Nanopore Technologies, sequences DNA or RNA strands by passing them through a nanopore gateway protein that works by recording and base-calling electrical current fluctuations as RNA or DNA molecules traverse the nanopore protein. This technology’s ability to perform parallel sequencing of multiple samples through multiplex barcoding makes it an enticing option for diagnosing grapevine viruses. This sequencing technology has demonstrated effectiveness in identifying various plant viruses across a wide range of hosts (Bronzato Badial et al., 2018; Chalupowicz et al., 2019; Fellers et al., 2019; Naito et al., 2019; Stenger et al., 2020). Recently, Javaran et al. (2023a) optimized this technology for the detection of grapevine viruses, including GLRaV-3. The study showed that this method is on par with second-generation sequencing in terms of accuracy, and also highlighted its cost-effectiveness at $22 per sample. Recent improvements in chemistry and flow cell features have further reduced the cost per sample and elevated the accuracy of this technology to 99.9 percent, putting it on par with other detection methods and underscoring its potential as a cost-effective and time-effective solution for grapevine virus detection.

SPATIAL DISTRIBUTION AND TEMPORAL SPREAD OF GLD

Due to clonal propagation of grapevines to preserve trueness-to-type and varietal integrity and the obligate and intracellular nature of viruses, the primary avenue for the spread of grapevine viruses is via infected planting stock. Consequently, it was generally believed until the 1980s that viruses such as GLRaV-3, hence GLD, spread in vineyards mainly due to the vegetative propagation and use of infected planting materials (Martelli, 2000). However, since 1989, field spread of GLD in vineyards was observed in grapevine-growing regions around the world, raising the suspicion that insect vectors might be contributing to the field spread. Several studies have recognized insects such as mealybugs (Pseudococcidae) and scale insects (Coccidae) as vectors responsible for vine-to-vine spread in vineyards (Naidu et al., 2014; Herrbach et al., 2017, and cited references). The fact that these vectors are relatively immobile means that vector-mediated

spread of GLD occurs relatively slowly compared to viral diseases spread by actively mobile vectors like aphids, whiteflies, thrips, and leafhoppers. Moreover, all stages of nymphs and mature female mealybugs lack wings and largely move by crawling (Daane et al., 2012). Female mealybugs are not capable of long-distance dispersal on their own, although it is often assumed that they can be dispersed by other means, such as human activities (e.g., via the distribution of vector-infested planting stock, on machinery used for vineyard shoot thinning and harvesting, and on vineyard workers’ clothing) and by wind and foraging birds. Unlike adult female mealybugs that live a mostly sedentary lifestyle, the first- and second-instar mealybug nymphs or “crawlers” are more important from the disease epidemiology perspective because of their mobility and higher transmission efficiency. The adult males are winged and can thus travel longer distances, but they are not involved in virus transmission since they have vestigial, nonfeeding mouthparts and do not feed (Daane et al., 2012).

Field studies were conducted in several grapevine-growing regions to better understand the epidemiology of GLD (Engelbrecht and Kasdorf, 1985; Habili and Nutter, 1997; Cabaleiro et al., 2008; Almeida et al., 2013; Pietersen et al., 2013; Sokolsky et al., 2013; Arnold et al., 2017; Bell et al., 2018; Donda et al., 2023). According to these studies, GLD generally spreads slowly between adjacent vines within a row and/or between neighboring rows, leading to clustering of symptomatic vines along individual rows. Monitoring GLD incidence in newly planted, healthy vineyard blocks showed a gradual increase in disease incidence over successive seasons. Analyzing spatio-temporal dynamics of disease spread by a variety of methods has revealed two distinct epidemiological patterns of GLD spread. In one pattern, the primary spread into a vineyard due to planting with compromised planting stock or introduction of the virus by alighting viruliferous vectors leads to an initial random distribution of GLD-affected vines. Randomly distributed symptomatic vines during initial years then serve as primary foci of infection for vine-to-vine secondary spread by colonized mealybugs within the vineyard, leading to clustering of symptomatic vines during subsequent seasons. With continued spread over multiple seasons, these random clusters of symptomatic vines within a vineyard expand over multiple seasons due to virus spread by viruliferous vectors, ultimately coalescing to cover the entire vineyard. In another pattern of spread, called “edge effect,” the virus is introduced to a newly planted, healthy vineyard via immigrating viruliferous vectors from virus-infected, established vineyards, which may be nearby or some distance away. The spatial and temporal spread of GLD in subsequent seasons leads to a disease gradient in which the highest percentage of vines showing GLD symptoms occurs in border rows proximal to nearby sources of infection with a gradual decline in disease incidence seen in vines that are farther from the established (and

infected) vineyard. These patterns of GLD spread appear to be similar in different wine regions across the world, irrespective of the vector species present in vineyards. The rate of vineyard spread can also be influenced by factors such as local environmental factors, cultivar and vector species composition, genetic diversity of the virus, and viticultural practices.

MANAGEMENT

Managing GLD is vital for maintaining the health and productivity of vineyards. As the most prevalent GLRaV, GLRaV-3 poses a significant threat to grapevines, impacting their quality and yield as well as nursery trade. Unfortunately, there is no known genetic resistance in grapevines to GLRaVs and there is no single, highly effective method for controlling GLRaV-3 infection and spread. Consequently, adopting an integrated approach is paramount for GLD prevention and mitigation.

Integrated approaches to GLD mitigation have demonstrated success in vineyards across South Africa and New Zealand (Almeida et al., 2013; Bell et al., 2021; Habili et al., 2022). In South Africa, a combination of practices, including applying herbicide to infected vines, using insecticide for mealybug control, and roguing of symptomatic vines and replanting resulted in a significant reduction in the GLRaV-3 infection rate. In one 41-hectare vineyard, for example, the infection rate decreased from 100 percent in 2002 to 0.027 percent in 2012 after these methods were employed (Pietersen et al., 2013). In New Zealand, the combination of vine removal and mealybug management led to a substantial reduction in infected vines over a 6-year period (Bell et al., 2018). In Napa, California, MacDonald et al. (2021) utilized five years of grower-sourced data to apply spatial and statistical models to better understand spatiotemporal trends in Ps. maritimus populations. Results showed that when GLD incidence within a block is less than 1 percent, consistent monitoring and removal of diseased vines is required to contain within-block spread. As incidence increases to 1-20 percent, both insecticide applications and roguing are effective, while at levels above 20 percent, roguing becomes critical for disease control.

At the regional scale, one crucial component of an integrated approach involves establishing a foundation stock, referred to as G1, which serves as the primary source of clean grapevine plants that are meticulously screened for GLRaV-3 before the establishment of G2, G3, and G4 blocks at nurseries (Golino et al., 2017). It is also a highly recommended practice to maintain an ongoing surveillance program within vineyards to monitor mealybug and soft scale vector populations and promptly remove GLRaV-3-infected vines (Pietersen et al., 2017). The success of this monitoring and testing step relies on the availability of rapid, early, cost-effective, and user-friendly detection methods (Javaran

et al., 2023a), which also support certification programs within the supply chain (Javaran et al., 2023b).

Recent advances in RNAi technologies have rekindled optimism for genetic engineering focused on imparting resistance to GLRaV-3 in grapevines. RNAi, a conserved endogenous process across eukaryotes, functions through sequence-specific RNA degradation or transcriptional gene repression within the silencing pathway (Baulcombe, 2004; Csorba et al., 2009). Initially identified as post-transcriptional gene silencing in plants during the early 1990s, RNAi acts as a molecular immune system, offering a robust primary defense against viruses when triggered by the appropriate inducer molecule in infected cells (Voloudakis et al., 2022). Utilizing RNAi, it is possible to develop transgenic grapevine plants resistant to GLRaV-3 by overexpressing hairpin RNA (hpRNA) or dsRNA from specific GLRaV-3 genes. This successful strategy has been employed against viruses including zucchini yellow mosaic virus, watermelon mosaic virus, potato virus X, and legume-infecting begomoviruses (Pooggin et al., 2003; Klas et al., 2006; Kumar et al., 2017). This approach also extends to exogenous applications, including RNAi-based bioproducts for controlling GLRaV-3 titers in grapevines (Avital et al., 2021), providing a promising and sustainable approach to managing GLRaV-3. This strategy can be seamlessly incorporated into broader integrated pest management (IPM) strategies. However, despite successful laboratory studies demonstrating the efficacy of dsRNA technology in managing plant diseases, its practical field implementation faces challenges due to the high production costs of dsRNA and the limited availability of necessary adjuvants and technologies (Voloudakis et al., 2022). The following sections outline key elements of integrated approaches to effectively manage GLRaV-3 that may be employed before planting (pre-plant) and those that may be employed after planting (post-plant).

Pre-Plant Management

Certified Planting Materials

Using vines that are tested virus-free as planting materials can help prevent the incursion of GLRaV-3 into vineyards.

Quarantine Measures

Adherence to federal quarantine measures guiding the movement of planting materials can help avoid introducing GLD into a vineyard.

Genetic Resistance

Developing and deploying cultivars and rootstocks that harbor genetic resistance to viruses is a desirable strategy for the management of viral diseases (Maule et al., 2007); however, no confirmed GLD-resistant grapevine has yet become available. Multiple factors make GLD resistance breeding efforts in Vitis spp. especially challenging, including the perennial nature of grapevine cultivation, the non-amenability of GLRaV-3 to mechanical transmission, and the low or non-uniformity of virus inoculum in grapevines, which makes vector-mediated screening efforts difficult to accomplish (Oliver and Fuchs, 2011). To circumvent these challenges, Jiao et al. (2022) recently employed an RNA-targeting CRISPR mechanism to induce resistance against GLRaV-3 in plantlets of V. vinifera cv. Cabernet Sauvignon. While the performance of these engineered vines is pending field evaluation under vineyard conditions, this approach presents new GLD management opportunities using biotechnology (Fuchs, 2023).

Post-Plant Management

Monitoring and Testing

It is important to regularly monitor vineyards for signs and symptoms of GLRaV-3 infection, such as leaf discoloration, leaf rolling, reduced fruit quality, and uneven ripening. Growers can implement a testing program to periodically check for the presence of GLRaV-3 in their vines.

Roguing

Roguing and destruction of GLRaV-3-infected vines as soon as they are identified can prevent or slow down the spread of the virus within a vineyard. Spatial roguing, the removal of virus-infected vines along with their two immediate neighbors, was tested in a New York vineyard to reduce the incidence of GLRaVs (Hesler et al., 2022). Over five years, this method, combined with replacing infected vines with virus-free stock, reduced virus incidence from 5 percent to less than 1 percent (Hesler et al., 2022). The experiment demonstrated that spatial roguing, even more than insecticide use, can significantly limit the spread of GLD, making it an effective management strategy in vineyards with low disease and pest pressure.

Vector Management

IPM practices, which can include various strategies such as the use of insecticides, pheromone traps, mating disruption, and beneficial insects,

can be used to control populations of GLRaV vectors such as mealybugs and soft scales. Also, controlling hemipteran-tending ants, such as the invasive Argentine ant, should be a key component of vineyard management strategies, as these ants disrupt biological control by protecting mealybugs from their natural predators (Cooper et al., 2019). Insecticide dissolved in 25 percent sugar water and toxin-laced polyacrylamide baits have proven effective in reducing ant populations, which allows natural enemies to better control mealybug infestations (Daane et al., 2006; Cooper et al., 2019;). Managing ant populations is crucial for establishing sustainable biological control, helping to maintain the balance between pests and their natural predators in vineyards. Since GLD can spread to nearby vineyards through vector dispersal, it is important to conduct vector control on a coordinated area-wide basis.

Grapevine Pruning and Canopy Management

Proper canopy management can limit contact between vines and reduce cross-vine movement of GLRaV-3-infective mealybugs and scale insect crawlers. Careful pruning is essential to prevent the spread of mealybug crawlers between vines.

Record Keeping

Maintaining records of GLRaV-3 testing and management activities can provide useful documentation to track progress and identify areas for improvement.

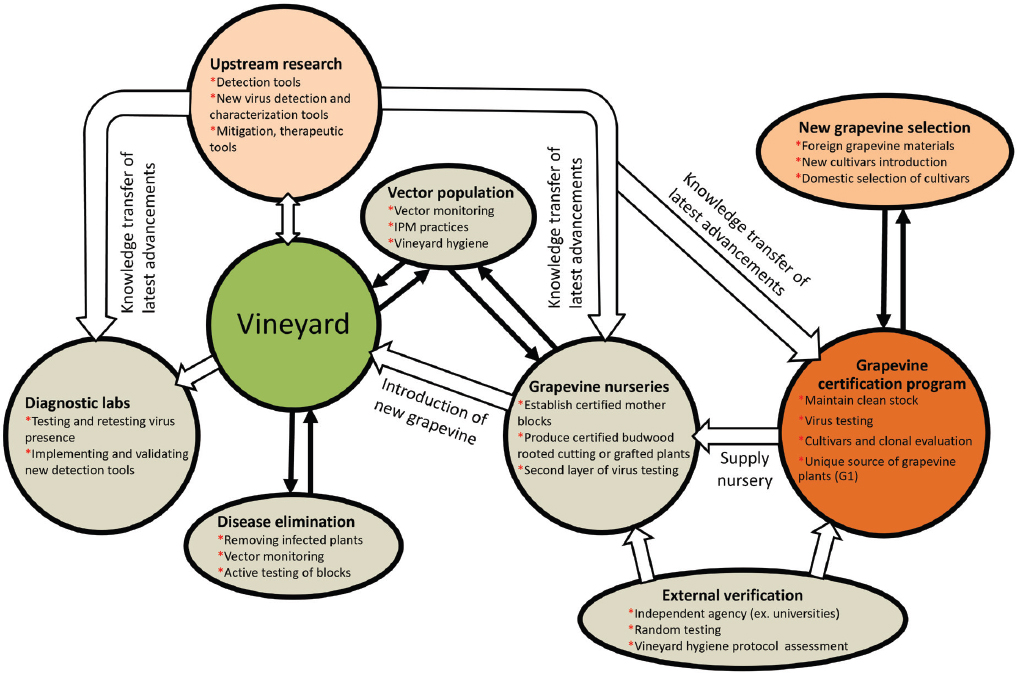

Holistic GLD Management

To identify points where effective management interventions could be implemented, it is essential to consider the entire grape production ecosystem (see Figure 3-6). Ultimately, combinations of different measures are more effective for GLD management than using any intervention alone (Bell et al., 2018; Chooi et al., 2024). For instance, Fuller et al. (2013) showed that losses due to GLRaV-3 are minimized when growers initially plant with certified stock and then rogue and replant with certified stock (Table 3-2), demonstrating the benefit of combining both management tactics for GLD management.

TABLE 3-2 Estimated Losses from GLD Under Different Vineyard Management Scenarios in California

| Case | Plantings | Replanting | Average Annual Discount/25 Years | Net Present Value/25 Years | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acre $/Acre/Year | Region $ Millions/Year | Acre $/Acre | Region $ Millions | |||

| 1 | Certified | Certified | 605 | 60.7 | 15,122 | 1,518.6 |

| 2 | Certified | Non-certified | 779 | 78.3 | 19,483 | 1,956.5 |

| 3 | Certified | No replanting | 790 | 79.3 | 19,745 | 1,982.8 |

| 4 | Non-certified | Certified | 914 | 91.8 | 22,847 | 2,294.4 |

| 5 | Non-certified | Non-certified | 1,138 | 114.3 | 28,449 | 2,857.0 |

| 6 | Non-certified | No replanting | 1,095 | 110.0 | 27,382 | 2,749.8 |

SOURCE: Fuller et al. (2013).

REFERENCES

Abou Ghanem-Sabanadzovic, N., S. Sabanadzovic, J. K. Uyemoto, D. Golino, and A. Rowhani. 2010. A putative new ampelovirus associated with grapevine leafroll disease. Archives of Virology 155:1871-1876.

Adiputra, J., S. Jarugula, and R. A. Naidu. 2019. Intra-species recombination among strains of the ampelovirus grapevine leafroll-associated virus 4. Virology Journal 16:139.

Agranovsky, A. A., D. E. Lesemann, E. Maiss, R. Hull, and J. G. Atabekov. 1995. “Rattlesnake” structure of a filamentous plant RNA virus built of two capsid proteins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 92:2470-2473.

Alabi, O. J., M. Al Rwahnih, G. Karthikeyan, S. Poojari, M. Fuchs, A. Rowhani, and R. A. Naidu. 2011. Grapevine leafroll-associated virus 1 occurs as genetically diverse populations. Phytopathology 101:1446-1456.

Alabi, O. J., L. F. Casassa, L. R. Gutha, R. C. Larsen, T. Henick-Kling, J. Harbertson, and R. A. Naidu. 2016. Impacts of grapevine leafroll disease on fruit yield and grape and wine chemistry in a wine grape (Vitis vinifera L.) cultivar. PLoS ONE 11:e0149666.

Al Rwahnih, M., P. Saldarelli, and A. Rowhani. 2017. Grapevine leafroll-associated virus 7. In Grapevine viruses: Molecular biology, diagnostics, and management, edited by B. Meng, G. P. Martelli, D. A. Golino, and M. Fuchs. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. Pp. 221-228.

Alkowni, R., A. Rowhani, S. Daubert, and D. Golino. 2004. Partial characterization of a new ampelovirus associated with grapevine leafroll disease. Journal of Plant Pathology 86:123-133.

Almeida, R. P. P., K. M. Daane, V. A. Bell, G. K. Blaisdell, M. L. Cooper, E. Herrbach, and G. Pietersen. 2013. Ecology and management of grapevine leafroll disease. Frontiers in Microbiology 4:1-13.

Alzhanova, D. V., Y. Hagiwara, V. V. Peremyslov, and V. V. Dolja. 2000. Genetic analysis of the cell-to-cell movement of beet yellows closterovirus. Virology 268(1):192-200.

Alzhanova, D. V., A. J. Napuli, R. Creamer, and V. V. Dolja. 2001. Cell-to-cell movement and assembly of a plant closterovirus: Roles for the capsid proteins and Hsp70 homolog. The EMBO Journal 20:6997-7007.

Arnold, K., D. A. Golino, and N. McRoberts. 2017. A synoptic analysis of the temporal and spatial aspects of grapevine leafroll disease in a historic Napa vineyard and experimental vine blocks. Phytopathology 107(4):418-426.

Atallah, S. S., M. I. Gómez, M. F. Fuchs, and T. E. Martinson. 2012. Economic impact of grapevine leafroll disease on Vitis vinifera cv. Cabernet franc in Finger Lakes vineyards of New York. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture 63:1. https://www.ajevonline.org/content/63/1/73_(accessed August 28, 2024).

Atallah, O. O., S.-H. Kang, C. A. El-Mohtar, T. Shilts, M. Bergua, and S. Y. Folimonova. 2016. A 5′-proximal region of the citrus tristeza virus genome encoding two leader proteases is involved in virus superinfection exclusion. Virology 489:108-115.

Avgelis, A., and D. Boscia. 2001. Grapevine leafroll-associated closterovirus 7 in Greece. Phytopathologia Mediterranea 40:289-292.

Avital, A., N. S. Muzika, Z. Persky, A. Karny, G. Bar, Y. Michaeli, J. Shklover, J. Shainsky, H. Weissman, O. Shoseyov, and A. Schroeder. 2021. Foliar delivery of siRNA particles for treating viral infections in agricultural grapevines. Advanced Functional Materials 31(44):2101003.

Bronzato Badial, A. B., D. Sherman, A. Stone, A. Gopakumar, V. Wilson, W. Schneider, and J. King. 2018. Nanopore sequencing as a surveillance tool for plant pathogens in plant and insect tissues. Plant Disease 102(8):1648-1652.

Bahder, B. W., S. Poojari, O. J. Alabi, R. A. Naidu, and D. B. Walsh. 2013. Pseudococcus maritimus (Hemiptera: Pseudococcidae) and Parthenolecanium corni (Hemiptera: Coccidae) are capable of transmitting grapevine leafroll-associated virus 3 between Vitis x labruscana and Vitis vinifera. Environmental Entomology 42:1292-1298.

Basso, M. F., T. V. M. Fajardo, H. P. Santos, C. C. Guerra, R. A. Ayub, and O. Nickel. 2010. Leaf physiology and enologic grape quality of virus-infected plants. Tropical Plant Pathology 35:351-59.

Baulcombe, D. 2004. RNA silencing in plants. Nature 431:356-363.

Bell, V. A., R. G. E. Bonfiglioli, J. T. S. Walker, P. L. Lo, J. F. Mackay, and S. E. McGregor. 2009. Grapevine leafroll-associated virus 3 persistence in Vitis vinifera remnant roots. Journal of Plant Pathology 91:527-533.

Bell, V. A., D. I. Hedderley, G. Pietersen, and P. J. Lester. 2018. Vineyard-wide control of grapevine leafroll-associated virus 3 requires an integrated response. Journal of Plant Pathology 100:399-408.

Bell, V. A., P. J. Lester, G. Pietersen, and A. J. Hall. 2021. The management and financial implications of variable responses to grapevine leafroll disease. Journal of Plant Pathology 103:5-15.

Belli, G., A. Fortusini, P. Casati, L. Belli, P. A. Bianco, and S. Prati. 1994. Transmission of a grapevine leafroll-associated closterovirus by the scale insect Pulvinaria vitis L. Rivista di Patologia Vegetale 4:105-108.

Bendel, N., A. Kicherer, A. Backhaus, J. Köckerling, M. Maixner, E. Bleser, H.-C. Klück, U. Seiffert, R. T. Voegele, and R. Töpfer. 2020. Detection of grapevine leafroll-associated virus 1 and 3 in white and red grapevine cultivars using hyperspectral imaging. Remote Sensing 12(10):1693. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs12101693 (accessed August 28, 2024).

Bertamini, M., and N. Nedunchezhian. 2002. Leaf age effects on chlorophyll, Rubisco, photosynthetic electron transport activities and thylakoid membrane protein in field grown grapevine leaves. Journal of Plant Physiology 159:799-803.

Blaisdell, G. K., S. Zhang, J. R. Bratburd, K. M. Daane, M. L. Cooper, and R. P. P. Almeida. 2015. Interactions within susceptible hosts drive establishment of genetically distinct variants of an insect-borne pathogen. Journal of Economic Entomology 108(4):1531-1539.

Blouin, A. G., K. M. Chooi, D. Cohen, and R. M. MacDiarmid. 2017. Serological methods for the detection of major grapevine viruses. In Grapevine viruses: Molecular biology, diagnostics and management, edited by B. Meng, G. P. Martelli, D. A. Golino, and M. Fuchs. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. Pp. 409-429.

Boonham, N., K. Walsh, P. Smith, K. Madagan, I. Graham, and I. Barker. 2003. Detection of potato viruses using microarray technology: towards a generic method for plant viral disease diagnosis. Journal of Virological Methods 108(2):181-187. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0166-0934(02)00284-7.

Borgo, M., E. Angelini, and R. Flamini. 2003. Effetti del virus GLRaV-3 dell’accartocciamento fogliare sulle produzioni ditre vitigni [Effects of the GLRaV-3 leaf curl virus on the production of three grape varieties]. L’Enologo 39:99-110.

Brock, T. D. 1999. Robert Koch: A life in medicine and bacteriology. American Society of Microbiology Press: Washington, D.C. 364 p.

Buja, I., E. Sabella, A. G. Monteduro, S. Rizzato, L. Bellis, V. Elicio, L. Formica, A. Luvisi, and G. Maruccio. 2022. Detection of ampelovirus and nepovirus by lab-on-a-chip: A promising alternative to ELISA test for large scale health screening of grapevine. Biosensors (Basel) 12(3):147, https://doi.org/10.3390/bios12030147 (accessed August 28, 2024).

Burger, J. T., H. J. Maree, P. Gouveia, and R. A. Naidu. 2017. Grapevine leafroll-associated virus 3. In Grapevine viruses: Molecular biology, diagnostics and management, edited by B. Meng, G. P. Martelli, D. A. Golino, and M. Fuchs. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. Pp. 167-195.

Cabaleiro, C., and A. Segura. 1997. Field transmission of grapevine leafroll associated virus 3(GLRaV-3) by the mealybug Planococcus citri. Plant Disease 81:283-287.

Cabaleiro, C., A. Segura, and J. J. Garcia-Berrios. 1999. Effects of grapevine leafroll-associated virus 3 on the physiology and must of Vitis vinifera L. cv. Albariño following contamination in the field. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture 50:40-44.

Cabaleiro, C., C. Couceiro, S. Pereira, M. Cid, M. Barrasa, and A. Segura. 2008. Spatial analysis of grapevine leafroll-associated virus 3 epidemics. European Journal of Plant Pathology 121:121-130.

Castellano, M. A., G. P. Martelli, and V. Savino. 1983. Virus-like particles and ultrastructural modifications in the phloem of leafroll-affected vines. Vitis 22:23-39.

Chalupowicz, L., A. Dombrovsky, V. Gaba, N. Luria, M. Reuven, A. Beerman, O. Lachman, O. Dror, G. Nissan, and S. Manulis-Sasson. 2019. Diagnosis of plant diseases using the Nanopore sequencing platform. Plant Pathology 68(2):229-238.

Chen, A. Y. S., G. P. Walker, D. Carter, and J. C. K. Ng. 2011. A virus capsid component mediates virion retention and transmission by its insect vector. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 108(40):16777-16782.

Chiba, M., J. C. Reed, A. I. Prokhnevsky, E. J. Chapman, M. Mawassi, E. V. Koonin, J. C. Carrington, and V. V. Dolja. 2006. Diverse suppressors of RNA silencing enhance agroinfection by a viral replicon. Virology 346(1):7-14.

Chooi, K. M., V. A. Bell, A. G. Blouin, M. Sandanayaka, R. Gough, A. Chhagan, R. M. MacDiarmid. 2024. Chapter Three—The New Zealand perspective of an ecosystem biology response to grapevine leafroll disease. In Advances in Virus Research, Volume 118, edited by R. M. MacDiarmid, B. Lee, and M. Beer. Academic Press. Pp. 213-272,

Choueiri, E., D. Boscia, M. Digiaro, M. A. Castellano, and G. P. Martelli. 1996. Some properties of a hitherto undescribed filamentous virus of the grapevine. Vitis 35:91-93.

Cocco, A., A. Mura, E. Muscas, and A. Lentini. 2018. Comparative development and reproduction of Planococcus ficus and Planococcus citri (Hemiptera: Pseudococcidae) on grapevine under field conditions. Agricultural and Forest Entomology 20:104-112.