Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Work (2025)

Chapter: 3 Artificial Intelligence and Productivity

3

Artificial Intelligence and Productivity

Productivity growth (see Box 3-1) is the most important determinant of higher long-run living standards. In turn, improvements in technology, especially general-purpose technology, are key to better productivity growth. The most promising general-purpose technology of the present era is artificial intelligence (AI). AI has increased productivity substantially for certain tasks, but thus far its impact on aggregate productivity has been minimal—which is to be expected because adoption is still relatively low. Because AI can apply to so many tasks in the economy and adoption is growing rapidly, however, its productivity impact this decade could be quite large. Harnessing the full potential of AI will take time and will require complementary investments and innovations in tangible and intangible capital, including human capital, organizational processes, and business models.

This chapter argues that AI is a general-purpose technology. It has the potential to influence every sector of the economy, it is rapidly improving, and it is fostering a vast array of applications. The chapter reviews some historical trends in productivity growth, including how it has varied over time and across sectors, industries, firms, and regions. It then explores AI’s effects on productivity, noting its relatively low adoption rate so far but its rapid growth and high potential for productivity contributions. Because AI is ultimately about creating a new form of replicable and extensible intelligence, and because intelligence is so fundamental to solving many of the world’s problems, AI may ultimately be viewed as the most general of all general-purpose technologies.

The chapter looks especially closely at generative AI, the most recent wave of AI, with some early case examples of its productivity effects and estimates of its broader

BOX 3-1 What Is Productivity Growth?

Productivity is defined as the amount of output produced per unit input. The greater the productivity, the greater the amount of goods and services that can be produced by an economy’s labor, capital, and natural resources. Productivity makes it easier to address many challenges in areas as diverse as poverty reduction, better health care, improved environment, stronger national defense, and reduced budget deficits.a By definition, productivity growth does not come from working longer hours. Instead, it comes from using labor and other inputs more effectively.

The most common productivity metric is labor productivity, typically defined as gross domestic product (GDP) per labor hour. Another useful metric is total factor productivity, which also includes capital as well as labor in the denominator. Adjustments in productivity metrics, although imperfect, can be made for capital quality, labor quality, capacity utilization, intangibles, and other factors.

__________________

a For instance, the Congressional Budget Office projects that if productivity growth ends up being 0.5 percentage points higher than its baseline, the projected debt/GDP ratio for the United States would be about 40 percent lower by 2052. See Congressional Budget Office, 2022, “The 2022 Long-Term Budget Outlook,” July 27, https://www.cbo.gov/publication/57971.

effects on the economy.1 Because there are important differences in the exposure of different sectors and occupations to generative AI, aggregate productivity effects will depend on how generative AI affects the productivity of different sectors, different occupations, and different firms, and there is likely to be significant heterogeneity across all categories. Generative AI can complement labor, substitute for labor, or facilitate labor redeployment into new activities. All three of these effects can boost labor productivity over time, but they will have different effects on the distribution of benefits and on the lags, barriers, and costs.

This chapter develops a framework for predicting AI’s productivity effects and identifies the following factors that will affect AI adoption and the size of these effects over time:

- The share of the economy where the technology can be applied,

- The size of the potential productivity effect in those applications,

- Complements and bottlenecks,

___________________

1 There have been important advances in other areas of AI, but as discussed in Chapter 2, the progress in most of these areas, such as the fine motor skills necessary to deploy AI in smart robots and production systems, has significantly lagged the progress in generative AI.

- Time lags,

- Positive and negative economic spillovers and rent seeking,

- Heterogeneity of effects within and across businesses and sectors,

- Measurement issues, and

- Dynamic effects.

Most of these factors, such as the need for complementary investments, the issue of time lags, and the problem of measurement gaps, have also affected the adoption rate of previous technologies, impeding or slowing their productivity effects. But there are also possible differences in AI adoption and its aggregate productivity effects. One difference stems from the relatively greater breadth of AI’s potential applications in so many parts of the economy, from agriculture to manufacturing to services.

A second and related difference stems from the fact that a very large percentage of tasks and occupations are exposed to AI, where exposure includes both AI as a substitute for human labor and AI as a complement to human labor. Rapid AI deployment could cause considerable disruption in the labor market as workers move between tasks and occupations. This disruption could weaken AI’s productivity effects if labor reallocation does not occur rapidly and if displaced workers are not deployed into new tasks with productivity levels at least as high as those in their previous tasks.

A third difference is the fact that many of the complementary investments to use AI—for example, investments in data, in computing power, and in the cloud—are already in place, enabling businesses to deploy AI rapidly on top of their existing infrastructure and system. To many users, generative AI is just a new app or website, or even a new feature within an existing app.

A fourth difference is that generative AI is by its nature creative—it can accelerate the process of scientific discovery and boost innovation, leading to a faster rate of change in productivity. In the long run, the slope of change in productivity is more important than its level. Over time, even small changes in the rate of growth compound to become significant.

Although there is considerable uncertainty about the size and the timing of the increase in productivity resulting from AI, the chapter concludes that the increase is likely to be quite large over the coming decade. But it raises questions and concerns about how the benefits of greater productivity from AI will be shared. Will the benefits be inclusive, or will they result in more income and wealth inequality? Will significant job losses occur as AI is used primarily to automate existing jobs rather than to augment worker skills and create new job opportunities? Will wage growth continue to lag productivity growth as it has over the past 20–30 years during periods of both strong productivity growth and slow productivity growth?

Even if generative AI results in significantly higher productivity, history suggests that without institutional and policy changes, it is unlikely that the benefits will be shared widely. The benefits may be accompanied by significant disruption in the labor market, and many workers, including many highly paid cognitive workers with advanced educational credentials, may experience job loss, the need to develop new skills, and downward wage pressure. In addition, the use of AI to monitor and surveil worker performance to squeeze additional labor productivity may erode job quality, worker satisfaction, and worker commitment. Institutions and policies like labor market regulations, training policies, and tax policies can mitigate these effects.

Last, although the chapter focuses on AI’s effects on productivity, it ends with a brief discussion of how AI may affect other measures of human well-being such as social progress and happiness as well as how it poses significant risks that could undermine human well-being, including risks to privacy, risks of discrimination and bias, risks to democracy and political stability, ethical risks, national security risks, risks of military arms races driven by new AI weapons, and even existential risks. In the words of Ian Bremmer and Mustafa Suleyman, “The decentralized nature of AI development and the core characteristics of the technology, such as open-source proliferation, increase the likelihood that it will be weaponized by cybercriminals, state-sponsored actors, and lone wolves.”2

ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE: A GENERAL-PURPOSE TECHNOLOGY

Although adoption of AI so far is limited, AI is a general-purpose technology, much like the steam engine and electricity. Historically, general-purpose technologies have been responsible for driving most economic growth and transformation. As defined by Bresnahan and Trajtenberg, general-purpose technologies have three essential characteristics: (1) they are pervasive, (2) they improve over time, and (3) they spawn complementary innovations.3

AI meets all three criteria:

- AI has the potential to influence nearly every sector of the economy. AI can add intelligence to robots and production systems in manufacturing, transportation, and logistics. AI, especially large language models (LLMs) and

___________________

2 I. Bremmer and M. Suleyman, 2023, “The AI Power Paradox,” Foreign Affairs, August, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/world/artificial-intelligence-power-paradox.

3 T.F. Bresnahan and M. Trajtenberg, 1992, “General Purpose Technologies ‘Engines of Growth’?” NBER Working Paper No. w4148, August, https://ssrn.com/abstract=282685.

- other generative AI, is expected to have an extensive impact on knowledge and information work: about 80 percent of jobs have at least 10 percent of their tasks suitable for LLMs.4 In addition to LLMs, other types of foundation models5 can work with graphics, audio, video, and other types of content.

- AI is rapidly improving. As shown in Chapter 4, Figure 4-5, GPT-4 achieved 90 percent accuracy on the Uniform Bar Examination, while GPT-3 scored less than 20 percent. The 2023 AI Index6 documents dozens of other areas of rapid improvement. In addition, LLMs display considerable capabilities overhang, giving rise to emergent properties such as code-writing and language translation abilities that were not anticipated when the models were created. Since the release of ChatGPT, there have been numerous additional breakthroughs in LLMs, including integration of traditional software tools such as calculators and search engines with LLMs, and a new generation of LLMs that manipulate sound and video in addition to text.

- AI is generating a vast array of complementary innovations. One clear indicator of this is the vibrancy of the OpenAI plugin marketplace, which already boasts hundreds of applications. These plugins extend the capabilities of GPT and address many of its existing limitations. More generally, AI is a catalyst for improvements in many areas of science, engineering, health care, management, and even the arts.7

HISTORICAL CHANGES IN PRODUCTIVITY GROWTH

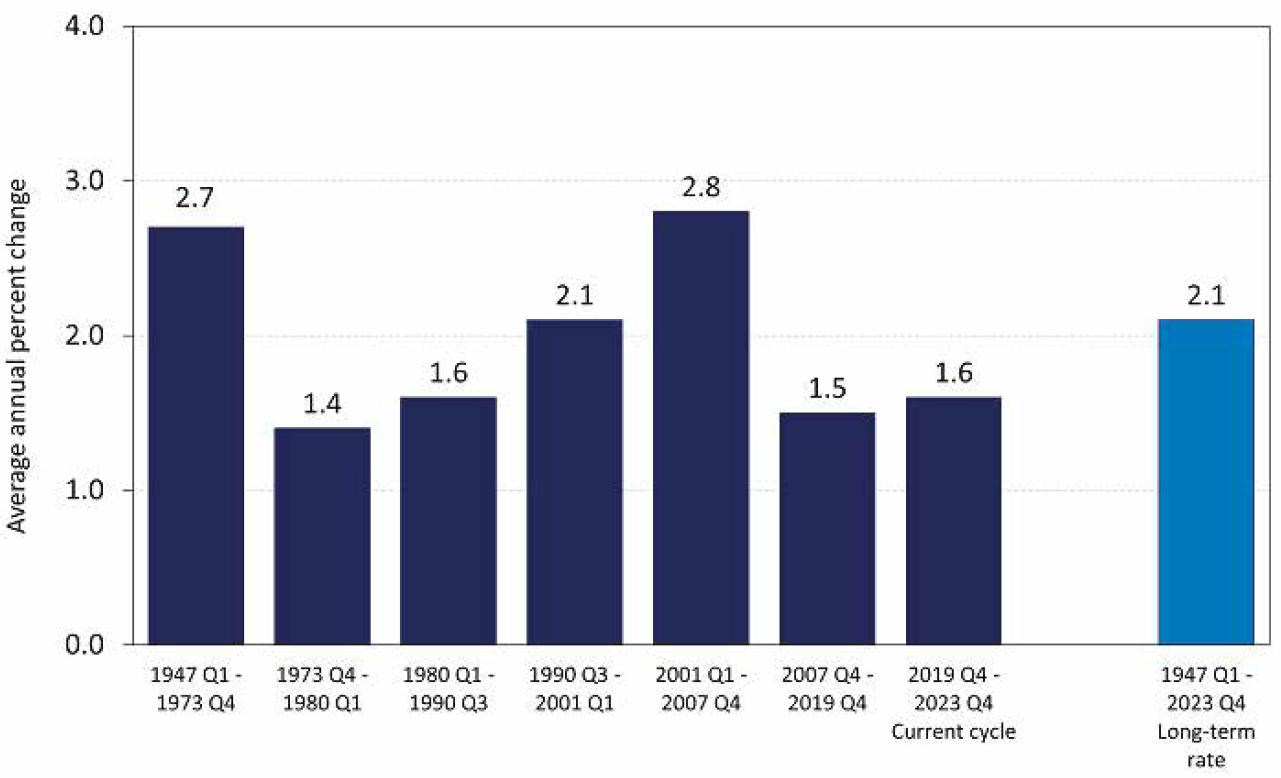

After a slowdown in 1973, labor productivity grew more rapidly in each business cycle but then slowed down substantially after 2007 (Figure 3-1).

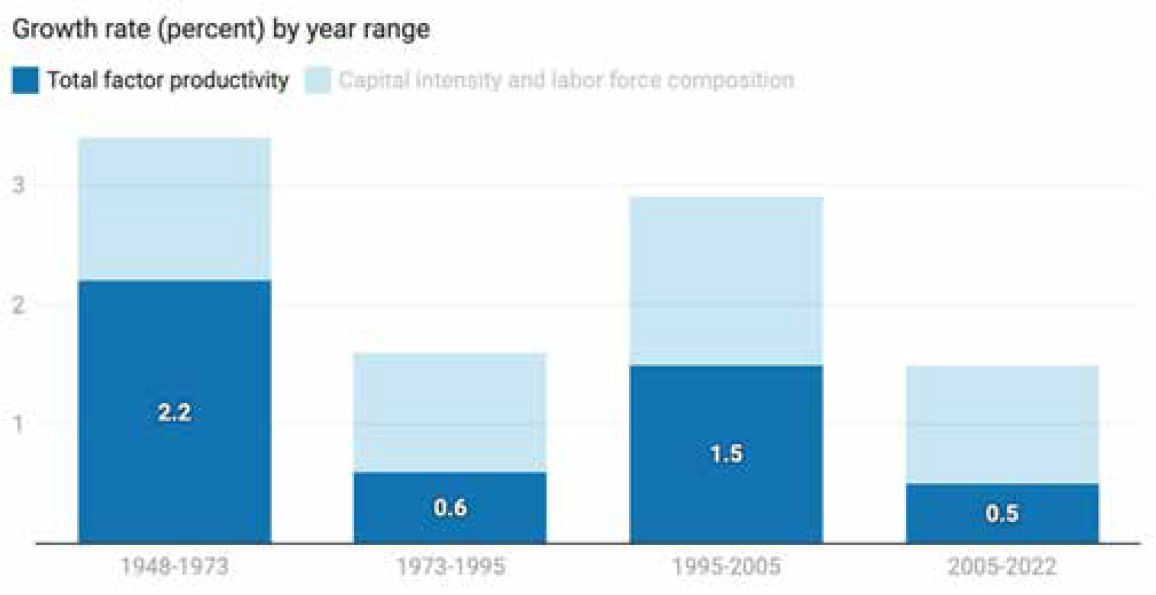

This slowdown reflected mainly a decrease in the growth of total factor productivity (TFP) (Figure 3-2), which has persisted through 2023.

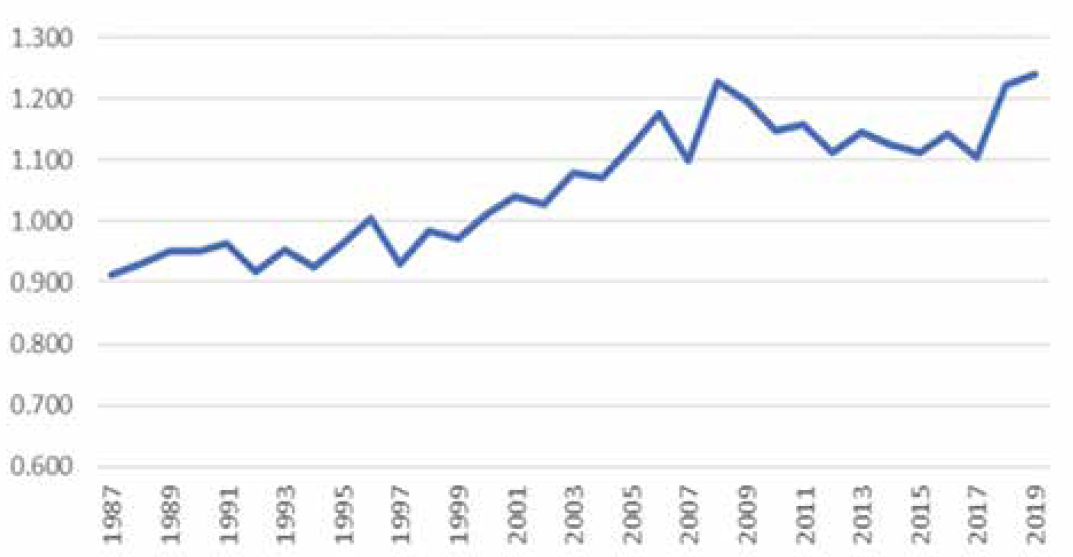

Part of the explanation of the slowdown in TFP growth is related to the business cycle, investment growth, and their interaction. Figure 3-3 shows that real gross private domestic investment in the United States grew strongly between 1990 and 2005, coincident with the introduction of the Internet and adoption of large enterprise

___________________

4 T. Eloundou, S. Manning, P. Mishkin, and D. Rock, 2023, “GPTs Are GPTs: An Early Look at the Labor Market Impact Potential of Large Language Models,” arXiv preprint, arXiv:2303.10130.

5 Foundation models are vast systems based on deep neural networks that have been trained on massive data sets and can be adapted to perform a wide range of tasks. See R. Bommasani, D.A. Hudson, E. Adeli, et al., 2022, “On the Opportunities and Risks of Foundation Models,” arXiv:2108.07258.

6 N.N. Maslej, ed., 2023, “Artificial Intelligence Index Report 2023,” Stanford University Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence, https://aiindex.stanford.edu/report.

7 See, for instance, the array of applications discussed in the essays brought together in Daedalus, 2022, 151(2).

SOURCE: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2024, “Long Term Labor Productivity by Sector for Selected Periods: Productivity Change in the Nonfarm Business Sector, 1947 Q1–2024 Q1,” last updated May 2, 2024, https://www.bls.gov/productivity/images/pfei.png.

SOURCE: Based on data from the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, n.d., “Total Factor Productivity,” https://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/indicators-data/total-factor-productivity-tfp, accessed August 1, 2024.

SOURCE: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, 2024, “Real Gross Private Domestic Investment [GPDIC1],” retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/GPDIC1.

information technology systems. It then fell during the 2007–2008 financial crisis and did not recover its 2006 peak until 2014.

Thereafter, real investment continued to rise, hitting a new peak in 2019, before declining sharply for a short time in 2020 as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic recession and recovering to a new peak in 2022. Overall, the macro environment affects not only business investment—the most procyclical component of spending—but also productivity growth. In particular, sluggish macroeconomic conditions, including the Great Recession of 2007–2009 and the COVID-19 pandemic recession of 2020–2021, slowed investment growth and capital deepening.

The anemic economic recovery after the Great Recession, with the macro economy operating below capacity and its potential for several years, also played a role in slower productivity growth. The Great Recession was sparked by a financial crisis that left many firms facing constraints on their investments in physical, intangible, and human capital. During the recovery, the decline in the growth of capital intensity per worker explains about one-third of the slowdown in labor productivity growth. But that slowdown actually began before the Great Recession, with labor productivity growth slowing each year from 2002 to 2006. TFP slowed precipitously across sectors and industries beginning in 2005–2006, which explains about 65 percent of the slowdown in labor productivity. In contrast, the composition of labor, a measure of the skills and experience of the workforce, was not a contributing factor to the productivity slowdown. Productivity growth from the composition of the workforce remained around 0.2–0.3 percentage points during the slowdown, similar to its long-run average.

How did productivity vary across industries? The slowdown in TFP growth in the United States in the 2005–2019 period was broad, affecting most sectors, industries, and geographies, albeit to differing extents.8 Overall, information and communications technology (ICT) producing and using industries—“high-tech” sectors—accounted for the surge in productivity growth between 1995 and 2004, and they led the significant decline thereafter. Byrne and colleagues provide compelling evidence of the role of these industries.9 Figure 3-4 shows patterns of growth rates of labor productivity in subperiods from 1990 to 2019 for high-tech and other industries. The widespread decline in productivity growth in both high-tech and non-high-tech industries in the post-2005 period is evident.

A 2023 study by McKinsey examines trends in productivity growth from 2005 through 2019. Mining, information, finance and insurance, and wholesale trade had the strongest productivity growth in the United States after 2005.10 With the exception of mining, which benefited from technical progress in natural gas, these sectors are among the most digitized and ICT-intensive of all sectors. The star productivity performer was the information sector—including software, telecommunications and Internet services, and publishing—which is the most digitized of all sectors.

Productivity growth in manufacturing, real estate, and utilities slowed after 2005 but continued to outpace the average. There are important differences, however, within the manufacturing sector, with the share of more productive research and development (R&D)-intensive subsectors expanding and the share of less productive labor-intensive subsectors declining. Within manufacturing, almost all of the TFP growth during the entire 1987–2019 period came from one industry: computer and electronics products. Surprisingly, and driving the slowdown in productivity in the manufacturing sector, this subsector appears to have experienced negative TFP growth between 2014 and 2019.

There were also significant differences in productivity growth within services. Between 2005 and 2019, labor productivity grew and converged toward the average in several services, including professional services, arts and entertainment, retail trade, and administrative services. Increasing digitization (e.g., e-commerce in retail and streaming services in arts and entertainment) was a major factor behind productivity gains in these services. In contrast, several labor-intensive service sectors, including accommodation and food service, health care, transportation, construction, and government services,

___________________

8 U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2021, “The U.S. Productivity Slowdown: An Economy-Wide and Industry-Level Analysis,” Monthly Labor Review, April, https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2021/article/the-us-productivity-slowdown-the-economy-wide-and-industry-level-analysis.htm.

9 D.M. Byrne, J.G. Fernald, and M.B. Reinsdorf, 2016, “Does the United States Have a Productivity Slowdown or a Measurement Problem?” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity (1):109–182, https://doi.org/10.1353/eca.2016.0014.

10 C. Atkins, O. White, A. Padhi, K. Ellingrud, A. Madgavkar, and M. Neary, 2023, “Rekindling US Productivity for a New Era,” McKinsey Global Institute, February 16, https://www.mckinsey.com/mgi/our-research/rekindling-us-productivity-for-a-new-era#.

NOTE: “High tech” refers to the science, technology, engineering, and mathematics–intensive sectors (including information and communications technology and biotechnology) as defined in D.E. Hecker, 2005, “High-Technology Employment: A NAICS-Based Update,” Monthly Labor Review 128:57.

SOURCE: Created based on data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Office of Productivity and Technology, “Industry Productivity Viewer,” https://data.bls.gov/apps/industry-productivity-viewer/home.htm.

remained productivity laggards with below-average productivity growth rates. Together, these lagging productivity sectors accounted for nearly one-quarter of output, about 37 percent of hours worked, and two-thirds of employment growth, slowing aggregate productivity growth as workers shifted into less productive work.

EXPLANATIONS FOR THE SLOWDOWN IN PRODUCTIVITY GROWTH

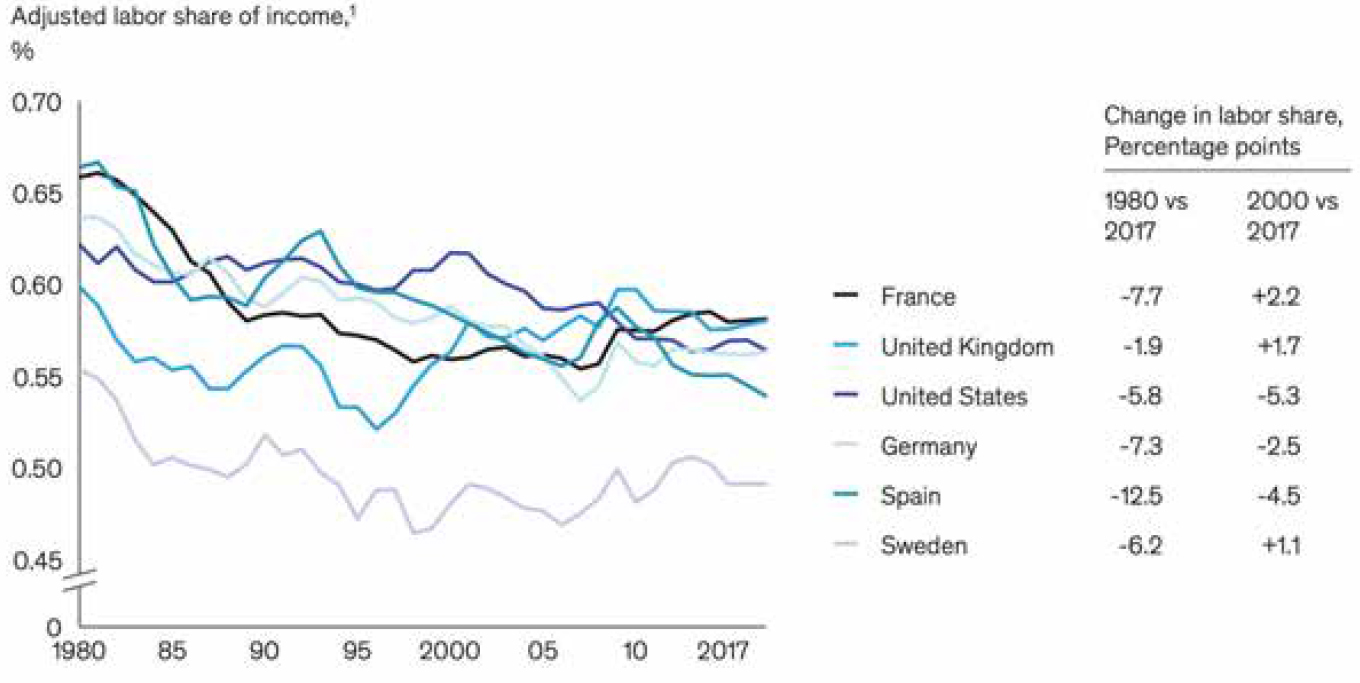

Economists differ on explanations for the significant, unexpected, and persistent slowdown in labor productivity growth and TFP growth, which occurred not just in the United States but in the other advanced economies after 2006.

As noted in the preceding section, all of these economies were hit by the Great Recession and an anemic recovery that slowed investment and contributed to slower productivity growth. Small businesses, including many entrepreneurial start-ups, were hit the hardest; fewer new small businesses were started, and many were closed. Commercial bank lending to support and grow new businesses declined as did venture capital, which set higher bars for start-ups seeking funding. Business uncertainty about the future replaced the business euphoria of strong shared growth around the world that characterized the years leading up to the Great Recession. And investment is

strongly negatively associated with higher uncertainty.11 Overall, an adverse and uncertain macroeconomic environment was a major factor behind the productivity slowdown in the United States and other advanced industrial economies hit by the Great Recession, which had global repercussions for growth and investment.

Another explanation for the slowdown in productivity growth is that advances in innovation and technology fluctuate over time. Robert Gordon provides extensive evidence of the fluctuations in the pace of technological advances.12 He argues that the ICT innovations of the 1980s and 1990s yielded significant gains in productivity, but the effects dissipated by the mid-2000s. Relatedly, Bloom and colleagues argue that research productivity has declined, as the inputs required to generate new advances have increased over time.13

Distinct but potentially related explanations are based on headwinds to productivity growth that have emerged over the past couple of decades. To provide guidance about these possible headwinds, it is instructive to review important structural changes in the economy since the 2000s. As the slowdown occurred, the productivity gaps among firms within sectors grew to unprecedented levels. The within-industry dispersion in TFP across establishments in the manufacturing sector has been rising, especially in the post-2000 period (Figure 3-5). While TFP is more difficult to measure at the firm level for other sectors, dispersion in labor productivity is rising across firms within industries in all sectors of the economy.14 Andrews and colleagues provide evidence of rising productivity dispersion within industries in many Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries as well.15

Many factors appear to underlie the rising gaps in productivity performance across firms. The gap measures reflect rising dispersion of revenue per unit input and can reflect not only rising gaps in technical efficiency but also rising frictions and distortions that can be a drag on advances in productivity.16,17 On the technical efficiency side, differences in the digitization of firms appear to be an important driver of differences in their

___________________

11 N. Bloom, S.J. Davis, L.S. Foster, S.W. Ohlmacher, and I. Saporta-Eksten, 2022, “Investment and Subjective Uncertainty,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series, No. 30654, November, https://doi.org/10.3386/w30654.

12 R. Gordon, 2017, “The Rise and Fall of American Growth: The US Standard of Living Since the Civil War,” Princeton University Press.

13 N. Bloom, C.I. Jones, J. Van Reenen, and M. Webb, 2020, “Are Ideas Getting Harder to Find?” American Economic Review 110(4):1104–1144, https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20180338.

14 R.A. Decker, J. Haltiwanger, R.S. Jarmin, and J. Miranda, 2020, “Changing Business Dynamism and Productivity: Shocks Versus Responsiveness,” American Economic Review 110(12):3952–3990, https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20190680.

15 D. Andrews, C. Criscuolo, and P.N. Gal, 2016, “The Best Versus the Rest: The Global Productivity Slowdown, Divergence Across Firms and the Role of Public Policy,” OECD Productivity Working Paper No. 05, November, https://www.oecd.org/global-forum-productivity/research/OECD%20Productivity%20Working%20Paper%20N°5.pdf.

16 Rising frictions and distortions can yield increases in misallocation such that resources (e.g., capital and labor) are allocated less efficiently.

17 C.-T. Hsieh and P.J. Klenow, 2009, “Misallocation and Manufacturing TFP in China and India,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 124(4):1403–1448, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40506263.

NOTE: Reported is the mean 90–10 within-industry differential of (log) total factor productivity across establishments across four-digit North American Industry Classification System industries in U.S. manufacturing.

SOURCE: Created based on data from U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics and U.S. Census Bureau, 2023, “Dispersion Statistics on Productivity,” https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/ces/data/public-use-data/dispersion-statistics-on-productivity.html.

productivity. There was a 70 percent correlation between a sector’s productivity growth and the level of its “digitization” during the past 30 years.18 In the United States within manufacturing, which includes both ICT producing and many ICT using sectors and businesses, leading businesses (firms at the 90th percentile of productivity) operated at four times the productivity level of laggards (businesses at the 10th percentile of productivity) in 2019. The comparable number in the semiconductor industry was 14 times the productivity level.19 Andrews and colleagues have suggested that an important factor underlying the rising productivity gaps among firms is slowing diffusion of technology as a result of rising frictions and distortions.20

The responsiveness of firms to changes in both their productivity performance and demand shocks appears to have slowed.21 This may be the result of a number of factors including rising dispersion in markups (prices above costs) and increases in political and

___________________

18 McKinsey Global Institute, 2023, “An Approach to Boosting US Labor Productivity,” May 25, https://www.mckinsey.com/mgi/our-research/an-approach-to-boosting-us-labor-productivity.

19 These statistics are drawn from the BLS/Census Dispersion Statistics on Productivity (DiSP) data product, https://www.bls.gov/productivity/articles-and-research/dispersion-statistics-on-productivity/home.htm. DiSP uses the Annual Survey of Manufactures and Census of Manufactures data.

20 D. Andrews, C. Criscuolo, and P.N. Gal, 2016, “The Best Versus the Rest: The Global Productivity Slowdown, Divergence Across Firms and the Role of Public Policy,” OECD Productivity Working Paper No. 05, November, https://www.oecd.org/global-forum-productivity/research/OECD%20Productivity%20Working%20Paper%20N°5.pdf.

21 R.A. Decker, J. Haltiwanger, R.S. Jarmin, and J. Miranda, 2020, “Changing Business Dynamism and Productivity: Shocks Versus Responsiveness,” American Economic Review 110(12):3952–3990, https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20190680.

economic uncertainty.22 These factors may have slowed the diffusion of new technologies across firms and increased the frictions associated with adjusting the scale and mix of operations at firms, including the adjustment of capital and labor.23

Accompanying the rising productivity gaps across firms has been a decline in measures of business dynamism and entrepreneurship. The rising frictions and distortions discussed above are potential mechanisms underlying this decline in dynamism. Figure 3-6 reports trends in a summary measure of business dynamism—the pace of job reallocation across establishments. Job reallocation is equal to the sum of the pace of job creation (expansions plus entering) and job destruction (contractions plus exiting). There has been a trend of decline in the pace of overall job reallocation since the late 1980s, but key innovative (“high-tech”) industries have exhibited a decline only in the post-2000 period.24 Preceding and accompanying the productivity surge from the high-tech industries in the 1990s, the pace of job reallocation rose in those industries from the 1980s through the early 2000s.

The share of employment at young firms exhibits broadly similar trends to the overall pace of job reallocation (Figure 3-7) with entrepreneurship surging in the high-tech industries in the 1990s through the early 2000s but declining thereafter. Detailed industry data show that the surge in entry preceded the surge in productivity in these innovation-intensive industries.25 These patterns are consistent with waves of experimentation, innovation, dynamism, and productivity growth over the 20th century.26

___________________

22 S.R. Baker, N. Bloom, and S.J. Davis, 2016, “Measuring Economic Policy Uncertainty,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 131(4):1593–1636, https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjw024 and J. De Loecker, J. Eeckhout, and G. Unger, 2020, “The Rise of Market Power and the Macroeconomic Implications,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 135(2):561–644, https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:oup:qjecon:v:135:y:2020:i:2:p:561-644.

23 J. De Loecker, T. Obermeier, and J. Van Reenen, 2022, “Firms and Inequality,” CEP Discussion Paper No. 1838, London School of Economics and Political Science, Centre for Economic Performance, London, investigates the implications of rising dispersion in markups for declining dynamism and productivity. U. Akcigit and S. Ates, 2021, “Ten Facts on Declining Business Dynamism and Lessons from Endogenous Growth Theory,” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 13(1):257–298, explores the contribution of slower diffusion for declining dynamism and productivity building in part on the evidence on declining diffusion in D. Andrews, C. Criscuolo, and P. Gal, 2016, “The Best Versus the Rest: The Global Productivity Slowdown, Divergence Across Firms and the Role of Public Policy,” OECD Productivity Working Paper No. 5, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/63629cc9-en. The role of rising adjustment costs for declining dynamism and productivity is explored in R.A. Decker, J. Haltiwanger, R.S. Jarmin, and J. Miranda, 2020, “Changing Business Dynamism and Productivity: Shocks Versus Responsiveness,” American Economic Review 110(12):3952–3990, https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20190680.

24 “High-tech” is the set of four-digit industries that are the most science, technology, engineering, and mathematics-intensive. See D.E. Hecker, 2005, “High-Technology Employment: A NAICS-Based Update,” Monthly Labor Review 128:57. This includes the ICT industries in manufacturing and nonmanufacturing and the scientific development industries (new AI firms are often classified in the latter).

25 C. Cunningham, L. Foster, C. Grim, et al., 2019, “Dispersion in Dispersion: Measuring Establishment-Level Differences in Productivity,” NBER Conference on Research in Income and Wealth, July 15–16, https://www.nber.org/conferences/si-2019-conference-research-income-and-wealth.

26 M. Gort and S. Klepper, 1982, “Time Paths in the Diffusion of Product Innovations,” Economic Journal 92(367):630–653, https://doi.org/10.2307/2232554. Gort and Klepper document that innovation takes time and has distinct phases. The early innovation phase is dominated by entry and experimentation, including investments in changes in organization. During this time productivity growth may decline with a rise in experimentally oriented misallocation. A shakeout process ensues with successful innovators expanding while unsuccessful innovators contract and exit. The successful innovators grow rapidly (becoming the large, successful firms of that wave of innovation) with accompanying productivity growth. Historically, these dynamics can be stretched across many years.

SOURCE: Created based on data from U.S. Census Bureau, Business Dynamic Statistics Datasets, https://www.census.gov/data/datasets/time-series/econ/bds/bds-datasets.html.

SOURCE: Created based on data from U.S. Census Bureau, Business Dynamics Statistics Datasets, https://www.census.gov/data/datasets/time-series/econ/bds/bds-datasets.html.

The flip side of the declining share of activity in young firms is the rising share of activity in large superstar firms.27 One way of characterizing this pattern is to examine the share of activity in “mega firms” (firms with more than 10,000 employees). The rise in mega firms has been particularly pronounced in nonmanufacturing high-tech industries in the post-2000 period (Figure 3-8).

Overall, structural changes on many different dimensions have collectively spurred productivity growth. Economic theory suggests that over time, more productive firms grow while less productive firms are replaced or are driven by competition to improve their performance. Such productivity-enhancing reallocation has been an important contributor to productivity growth over time.28 Relatedly, the innovative process itself is closely tied to the pace of reallocation, with young firms playing an outsized role in major innovations.29,30 Unfortunately, as shown above, during the productivity slowdown there has been a decline in the pace of business dynamism and entrepreneurship in the United States. This has included a decline in the pace of entrepreneurship in the innovation-intensive sectors of the economy that played such an important role in the productivity surge in the 1990s.

The shift toward large mature firms likely reflects many factors. First, powerful network effects and economies of scale effects are likely behind the emergence of a handful of global high-tech producing and using firms such as Google, Apple, Meta, Microsoft, and Amazon. Related rises in concentration have occurred beyond the high-tech sector as globalization and information technologies have favored large incumbents. While rising concentration reflects the substantial innovations by superstar firms, the accompanying decline in competition is consistent with the rise in the level and dispersion of markups of price over cost. The rise in concentration and the accompanying rise in the dispersion of markups, possibly working together, might account for some or all of the decline in dynamism and productivity.31

Important changes in the allocation of talent across firms have accompanied these changes in the structure of firms. Sorting and segregation of workers across firms have increased—more highly educated workers are more likely to be at firms that offer higher wages and better working conditions, and less educated workers are more likely to be

___________________

27 D. Autor, D. Dorn, L.F. Katz, C. Patterson, and J. Van Reenen, 2020, “The Fall of the Labor Share and the Rise of Superstar Firms,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 135(2):645–709, https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjaa004.

28 L. Foster, J.C. Haltiwanger, and C.J. Krizan, 2001, “Aggregate Productivity Growth: Lessons from Microeconomic Evidence,” pp. 303–372 in New Developments in Productivity Analysis, C.R. Hulten, E.R. Dean, and M.J. Harper, eds., University of Chicago Press, http://www.nber.org/chapters/c10129.

29 U. Akcigit and W. Kerr, 2018, “Growth Through Heterogeneous Innovations,” Journal of Political Economy 126(4):1374–1443.

30 D. Acemoglu, U. Akcigit, H. Alp, N. Bloom, and W. Kerr, 2018, “Innovation, Reallocation, and Growth,” American Economic Review 108(11):3450–3491, https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20130470.

31 R. Cherif, F. Hasanov, and P. Aghion, 2023, “Fair and Inclusive Markets: Why Dynamism Matters,” Global Policy 14(5):686–701, https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.13250.

SOURCE: Created based on data from U.S. Census Bureau, Business Dynamics Statistics Datasets, https://www.census.gov/data/datasets/time-series/econ/bds/bds-datasets.html.

in low-wage firms and sectors.32 These sorting and segregation effects have arguably reinforced the gaps between low- and high-productivity performers within sectors. Relatedly, Akcigit and Goldschlag find that over the post-2000 period, “inventors are increasingly concentrated in large incumbents, less likely to work for young firms, and less likely to become entrepreneurs.”33 Moreover, they find that an inventor’s earnings increase and innovative output decreases when hired by an incumbent as compared to a young firm. They argue that these patterns are consistent with large incumbent firms having strategic reasons to slow innovation so as not to cannibalize their existing products and market shares. Their findings reinforce concerns about the potentially adverse implications for innovation and productivity growth of both increasing concentration of large incumbents in many sectors, especially mega firms in high-tech sectors, and decreasing entrepreneurship.

In spite of these structural headwinds to productivity growth, AI may yield a new and sustained surge in investment and productivity. Much of the remaining part of the chapter addresses this possibility. It remains to be seen whether AI yields this surge by disrupting the macroeconomic and structural changes discussed in this section and rekindling business dynamism. There is some evidence from the past few years that the

___________________

32 J. Song, D.J. Price, F. Guvenen, N. Bloom, and T. von Wachter, 2019, “Firming Up Inequality,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 134(1):1–50, https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjy025.

33 U. Akcigit and N. Goldschlag, 2023, “Where Have All the ‘Creative Talents’ Gone? Employment Dynamics of US Inventors,” Working Paper 23-17, Center for Economic Studies, U.S. Census Bureau.

SOURCE: Created based on data from U.S. Bureau of the Census, Business Formation Statistics.

decline in business dynamism in the United States is being reversed. Business formation has been surging in the United States since 2020.34 Some of this surge is undoubtedly associated with the structural changes induced by the COVID-19 pandemic in terms of changes in work and lifestyle (e.g., there has been a surge in business formation in e-commerce). This surge in business formation has continued through the present. As of May 2023, applications for new businesses that signal they are likely to be new employers remained more than 30 percent higher than in 2019. Moreover, this surge in business formation is occurring in key high-tech industries—the Information sector (NAICS 51) and the Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services sector (NAICS 54)—as shown in Figure 3-9. New AI firms are likely to be classified in one of these two industries.

EFFECTS OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE ON PRODUCTIVITY

Overall Adoption Is Limited But Growing Rapidly

AI adoption in most firms is still low, but it has been gradually permeating economic activity over several years—for example, with the technology powering smartphones, in autonomous-driving features on cars, for digital retail sales via platforms like Amazon, for

___________________

34 J.C. Haltiwanger, 2021, “Entrepreneurship During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Evidence from the Business Formation Statistics,” pp. 9–42 in Entrepreneurship and Innovation Policy and the Economy, Vol. 1, National Bureau of Economic Research.

streaming services like Netflix, and in intelligent robots and intelligent systems in manufacturing. AI in the form of advanced analytics and machine learning algorithms has been effective at performing numerical optimization and predictive modeling in a wide range of industries.35

The adoption of AI tools has varied by firm characteristics and by sector. In the United States, larger, more highly digitized, and younger firms have been more likely to adopt AI.36 In addition, adoption has been higher at firms with younger, more educated, and more experienced owners.37 Overall, between 2016 and 2018, an estimated 13 percent of U.S. employees worked at firms using AI. Adoption rates also varied by industry; the largest percentages of firms with some AI adoption were found in information, financial services, management, and finance, and the largest percentages of workers with higher-than-average exposure rates to AI were found in these sectors as well as in retail trade transportation utilities and manufacturing.38,39

According to results in the 2019 Annual Business Survey for U.S. companies, the main barriers to AI adoption by a firm are inapplicability to its business and cost. Among AI-adopting firms, 80 percent (employment-weighted) adopted AI to improve product or service quality, 65 percent adopted AI to upgrade existing processes, and 54 percent adopted AI to automate existing processes. Acemoglu and colleagues also report that firms adopting AI have higher productivity and lower labor shares than similar firms, a result that is consistent with automation being a major application for AI.40 Of AI adopters, 15 percent reported an increase in employment and 6 percent reported a decrease, while 41 percent reported an increase in skill demand and none reported a decrease.

Although AI has affected specific applications and firms, to date the deployment of AI has been too small to have had a detectable effect on aggregate productivity growth or on productivity growth by industry. Indeed, the slowdown in TFP growth between 2005 and 2019 across sectors overlapped with the gradual roll-out of AI adoption.

___________________

35 M. Chui, E. Hazan, R. Roberts, et al., 2023, “The Economic Potential of Generative AI: The Next Productivity Frontier,” McKinsey & Company, June 14, https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/mckinsey-digital/our-insights/the-economic-potential-of-generative-ai-the-next-productivity-frontier.

36 It can be challenging to define precisely what it means to “adopt AI.” The following findings are drawn from the Annual Business Survey (ABS) of the U.S. Census, which targets owners and managers of about 850,000 U.S. firms of all sizes. The adoption question in the ABS starts with the following: “During the three years 2016 to 2018, to what extent did this business use the following technologies in production processes for goods or services?” Then for a series of technologies including AI, the responses possible are as follows: “Did not use; Tested but did not use in production or service; low use; moderate use; high use.” A series of follow-up questions draws out how and why they are using the technologies.

37 N. Zolas, Z. Kroff, E. Brynjolfsson, et al., 2020, “Advanced Technologies Adoption and Use by U.S. Firms: Evidence from the Annual Business Survey,” SSRN Electronic Journal, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3759827.

38 Ibid.

39 European Commission and the U.S. Council of Economic Advisors, 2022, “The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on the Future of Workforces in the European Union and the United States of America,” December 5, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/TTC-EC-CEA-AI-Report-12052022-1.pdf.

40 D. Acemoglu, G.W. Anderson, D.N. Beede, et al., 2022, “Automation and the Workforce: A Firm-Level View from the 2019 Annual Business Survey,” NBER Working Paper No. 30659, November, National Bureau of Economic Research, https://doi.org/10.3386/w30659.

A few cases illustrate the various ways that AI has been affecting key industries. The information industry is the most digitized industry and has the highest share of both firms and employment with some AI adoption. AI is being applied in the financial services industry for a variety of purposes including risk assessment and capital allocation, stewardship in asset management, fraud detection, algorithmic trading, faster services (e.g., mortgage approvals), and core back-office support and compliance tasks. There have also been numerous AI applications in the auto industry including design and development, manufacturing and warehouse processes, analysis of road conditions, personalized vehicles and enhanced safety, auto insurance, and dealership experience.41

Yet, as noted above, the information sector experienced a sharp and unexplained deceleration in TFP growth after 2005. Information technology firms have been both the developers and the early adopters of AI technologies. Finance too has relatively high shares of firms and employment with some AI adoption, and it too experienced a significant deceleration in productivity growth. Indeed, in the area of securities and other financial investments, changes in productivity growth went from strongly positive in 1997–2005 to strongly negative in 2005–2019. The finance industry was hit hard by the 2007–2008 global financial crisis and the restructuring that followed, with negative consequences for its productivity growth.

A Framework for Thinking About the Effects of AI on Aggregate Productivity

How much will AI affect aggregate productivity? It is an important question but also one that is inherently difficult to answer. TFP has been called “a measure of our ignorance” because, by definition, it cannot be directly accounted for by any measured inputs.42 Instead, it is the residual or unexplained additional output that is created after increases in capital and labor inputs are included.

Typically, this residual is interpreted as the result of technology broadly defined. This includes not only advances in equipment and machinery but also new production techniques and methods. Nonetheless, there are some key variables that will affect the magnitude of an increase in productivity growth that can be expected from a new technology such as AI. This section develops a framework for estimating the potential effects of AI on productivity and growth and for establishing bounds on how much additional growth to expect. The framework identifies eight key factors to consider.

A good place to start is with Hulten’s theorem, which states that for efficient economies and under minimal assumptions, the first-order impact on aggregate output

___________________

41 M. Singhal, S. Kadam, and S. Sahay, 2022, “29 AI Use Cases—Transforming the Automotive Industry,” Birlasoft, CK Birla Group, https://www.birlasoft.com/articles/ai-use-cases-in-automotive-industry.

42 M. Abramovitz, 1989, “Resource and Output Trends in the United States Since 1870,” pp. 127–147 in Thinking About Growth: And Other Essays on Economic Growth and Welfare, Studies in Economic History and Policy: USA in the Twentieth Century, Cambridge University Press, https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511664656.005.

of a TFP increase in an industry is proportional to that industry’s sales as a share of aggregate output.43 Hulten’s theorem gives the first two factors to consider: (1) the share of the economy that the technology affects and (2) the potential size of its productivity impact. For instance, if LLMs affect 50 percent of the tasks in the economy and make those tasks 20 percent more productive on average, then a first-order estimate of the net effect of LLMs on aggregative productivity would be 50 percent of 20 percent, or 10 percent.

But that is only a start. A third factor is that most new technologies require additional complementary investments in workers, tangible capital, and intangible capital in order to be used effectively. For example, complementary investments to train workers to use the technology may be required. New business processes and organizational forms can also be important complements to new technologies.44 Additional investment in physical capital may also be required. As an illustration, LLMs depend on training large neural networks that typically require significant investments in computing infrastructure. If such other investments are strict complements, meaning they are indispensable to using the new technology, then they can become bottlenecks. For instance, faster fiber-optic cables will generate no increase in bandwidth if they are not paired with suitable routers. Conceptually, if the production process in a manufacturing plant or industry consists of 1,000 steps that must be done in sequence, then speeding up 1 of them or even 999 of them will not increase throughput if at least one step remains a bottleneck.45 Thus the need for complements, particularly when they become bottlenecks, can reduce the aggregate productivity effects of AI below what might be expected from Hulten’s theorem.46

Over time, bottlenecks can be addressed. It’s not uncommon for a bottleneck to become a focus of attention because the returns from alleviating it can be very high. One reason that Moore’s law has advanced so consistently for more than 70 years is that whenever one aspect of the production process was not keeping up with the others, it

___________________

43 C.R. Hulten, 1978, “Growth Accounting with Intermediate Inputs,” Review of Economic Studies 45:511–518.

44 E. Brynjolfsson and P. Milgrom, 2012, “Complementarity in Organizations,” pp. 11–55 in The Handbook of Organizational Economics, R. Gibbons and J. Roberts, eds., Princeton University Press.

45 A related phenomenon is sometimes called “Baumol’s Cost Disease”; see W.D. Nordhaus, 2008, “Baumol’s Diseases: A Macroeconomic Perspective,” B.E. Journal of Macroeconomics 8(1):1–39. Even rapid productivity increases in one part of the economy will be dampened if other parts of the economy do not see an improvement. Over time, the productive sectors may require less labor and fall in cost. If demand does not grow commensurately, then the sectors with rapid productivity growth will shrink while the more stagnant sectors will become increasingly important.

46 In particular, Hulten’s theorem holds in a no frictions, no distortions, competitive (in output and factor markets) economy. The misallocation literature has emphasized that differences in productivity across countries, industries, and time depend critically on the frictions and distortions that inhibit the efficient allocation of resources. See C.-T. Hsieh and P.J. Klenow, 2009, “Misallocation and Manufacturing TFP in China and India,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 124(4):1403–1448, https://doi.org/10.1162/qjec.2009.124.4.1403. These frictions and distortions can impact both the level and growth of productivity. In Hulten’s economy, there is no dispersion in revenue productivity across firms because marginal revenue products are equalized instantaneously across firms (no markups, markdowns, other frictions, or distortions such as frictions in capital and labor markets). This perspective is not just that the productivity gains may take longer to be realized but also that they are dampened by the frictions and distortions inducing misallocation.

would draw attention, research, and investment. As bottlenecks are addressed, the long-run changes in output and productivity from a technology shock will tend to be larger in magnitude than the short-run changes.47

This highlights the role of time lags as a fourth factor. There are several reasons why the full impact of a new technology on productivity takes time. If the new technology changes tasks, jobs, and occupations—and the skills required for them—there could be considerable labor market disruption. The necessary labor market transitions could be substantial and costly. It also takes time to build and implement the new core technology as well as to implement complementary investments, which may include physical capital and infrastructure, human capital, and intangible assets. Furthermore, often the most effective combination of these assets is not well understood in advance and needs to be discovered by research or by experimentation. Overall, if a new technology can be expected ultimately to have a 10 percent effect on the level of productivity but it takes 10 years to fully implement, including time for the necessary redeployment of labor and time to create the necessary complements, then the technology’s average annual effect on productivity will be only about 1 percent.

A fifth factor to consider is that private returns do not necessarily add up to equal social returns. In particular, a new technology may cause positive or negative economic spillovers—benefits or costs for businesses and individuals that are not directly involved in purchasing or using the technology. These externalities can have a positive or a negative effect on aggregate productivity. For instance, the introduction of LLMs may trigger a cascade of complementary innovations that create a great deal of value beyond the value created by the initial investment. The ChatGPT plugin marketplaces are examples of this. And, as discussed below, AI’s tools for understanding protein folding are likely to create significant positive externalities in the pharmaceutical industry. With many general-purpose technologies like AI, complementary innovations ultimately do more to affect output and productivity than the initial innovation itself.

Spillovers can also be negative—for example, when AI is used for rent seeking or shifting market shares. For instance, a faster machine learning algorithm might make it possible to predict prices in a commodity market rapidly, allowing a trading firm to purchase or sell assets milliseconds before its competitors. That can result in large profits, but they largely come at the expense of others in the market. The social value of having the trade happen a few milliseconds earlier is negligible, but the private returns can be enormous. Similarly, some types of advertising may be aimed primarily at shifting market shares in a zero-sum way rather than increasing total market size or improving the match of products with customers. Relatedly, technology could allow for improved price discrimination and targeting, enabling sellers to capture consumer surplus from

___________________

47 P. Milgrom and J. Roberts, 1996, “The LeChatelier Principle,” American Economic Review 86(1):173–179.

buyers. Again, this can be very profitable without increasing total welfare. These kinds of negative business spillovers tend to be less of an issue in highly competitive markets, but AI could increase concentration, which would increase the potential for rent and thus rent-seeking behavior. More ominously, AI could create negative externalities by increasing cybersecurity risks and costs, by violating customer privacy, or by increasing the number and strength of homemade weapons or toxins.

Measurement issues are a sixth factor that should be considered when assessing the effects of a new technology on productivity, at least as it is conventionally reported. In particular, there are many benefits that are not captured in gross domestic product (GDP) and therefore are also missing from productivity. For instance, an AI-enabled innovation that leads to a new therapeutic drug may have some small direct effects on GDP when that drug is sold, but there may be even more important indirect effects if the drug leads to longer, healthier lives. Those health benefits generally will not show up in GDP or productivity. Health care is the top area for AI investment according to the 2023 edition of the AI Index report.48 In addition, many new products create far more consumer surplus than revenue. For instance, a free or low-cost version of a digital AI assistant might generate little or no business revenue but significant benefits for its users. In most cases, the small increase in revenue would be reflected in GDP, but the larger increase in consumer surplus generally would not be. William Nordhaus has estimated that more than 95 percent of the benefits of technological innovations ultimately end up in the hands of consumers not sellers.49

There are several alternative measures of well-being, including some that specifically focus on measuring consumer surplus.50,51 However, for now GDP and productivity are the primary metrics of economic growth used in the national accounts and by business, government, and the media.

The seventh factor to consider is substantial heterogeneity in the productivity effect of a new technology across sectors, firms, workers, and tasks. As noted earlier, there is evidence of a growing gap in the revenue productivity of the top 5 percent of firms in an industry in a given year (“the best”) compared to the remainder of firms (“the

___________________

48 N. Maslej, L. Fattorini, E. Brynjolfsson, et al., 2023, “The AI Index 2023 Annual Report,” AI Index Steering Committee, Institute for Human-Centered AI, Stanford University, April, https://aiindex.stanford.edu/ai-index-report-2023.

49 W. Nordhaus, 2004, “Schumpeterian Profits in the American Economy: Theory and Measurement,” NBER Working Paper No. 10433, National Bureau of Economic Research.

50 M. Fleurbaey, 2009, “Beyond GDP: The Quest for a Measure of Social Welfare,” Journal of Economic Literature 47(4):1029–1075.

51 E. Brynjolfsson, A. Collis, W.E. Diewert, F. Eggers, and K.J. Fox, 2019, “GDP-B: Accounting for the Value of New and Free Goods in the Digital Economy,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. w25695.

rest”).52 While this could be owing to a variety of causes,53 it may reflect a growing gap between leaders and laggards in technology adoption and use. If AI exacerbates this trend, then looking only at average productivity may miss the growing heterogeneity in performance.

Last, it should be noted that the economy is not static, so the dynamic effects of technology are the eighth and final factor that should be considered.54 In the long run, the rate of change in productivity is more important than its level. AI can boost innovation itself, leading to a faster rate of change, not just a one-time boost. Over time, even small changes in the rate of growth compound to become significant. One promising aspect of recent AI advances is that tools like LLMs make it easier for larger and more diverse groups of people to contribute to innovation. For instance, the prompts used to direct LLMs can be written in English and do not require learning programming languages like Python or C. Furthermore, even in applications where such languages are needed, coding can increasingly be done using natural language interfaces, leveraging tools such as GitHub Copilot.

In sum, these eight factors provide a framework for understanding how AI, like other technologies, can affect productivity and well-being. Hulten’s theorem can provide the initial first-order estimate, based on the first two factors, highlighting that the aggregate effect is a function of all eight factors.

It is possible to develop estimates of some of these effects that can help put upper and lower bounds on the likely productivity impact of AI. That said, there will be uncertainties in all of the variables, so this framework is important less for the sake of getting precise predictions and more for getting a sense of where the main sources of uncertainty are and where the biggest policy levers are likely to be.

The following subsections go into more detail on each of these factors.

Factor 1: Share of the Economy Potentially Affected by AI

A major reason AI may significantly boost labor productivity growth is that it has potential applications in so many parts of the economy. Generative AI along with other types of AI and robotics have the potential to affect activities that today encompass a majority

___________________

52 See, for example, D. Andrews, C. Criscuolo, and P. Gal, 2015, “Frontier Firms, Technology Diffusion and Public Policy: Micro Evidence from OECD Countries,” OECD Productivity Working Paper No. 2, OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/5jrql2q2jj7b-en; and E. Brynjolfsson, A. McAfee, M. Sorell, and F. Zhu, 2008, “Scale Without Mass: Business Process Replication and Industry Dynamics,” Harvard Business School Technology and Operations Management Unit Research Paper No. 07-016, September 30, http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.980568.

53 Revenue productivity dispersion is revenue per unit input, and it potentially reflects many factors, including (1) rising dispersion of distortions and/or frictions impeding the equalization of marginal revenue products (e.g., rising uncertainty, adjustment costs); (2) rising dispersion of markups; (3) rising dispersion in fundamentals in the presence of a given set of frictions/distortions impeding the equalization of marginal revenue products; (4) rising correlation between fundamentals and distortions/frictions (e.g., markups rising especially for the largest firms); and (5) rising dispersion in within-industry differences in production processes.

54 M.N. Baily, E. Brynjolfsson, and A. Korinek, 2023, “Machines of Mind: The Case for an AI-Powered Productivity Boom,” Brookings Institution, May 10, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/machines-of-mind-the-case-for-an-ai-powered-productivity-boom.

of worker time. There is no perfect way to assess the tasks that will be affected. Eloundou and colleagues assess the alignment of occupations with LLM capabilities and find that LLMs alone could affect 80 percent of the U.S. workforce to some degree and affect, either as a complement or substitute, over half of the tasks done by 19 percent of the workforce.55 Furthermore, there are other types of AI, including machine learning used for classification and prediction tasks, that are suitable for thousands of other tasks.56 The net effect of AI on tasks will thus be quite widespread.

The set of tasks that can be affected by AI has expanded significantly over the past decade. The costly process of creating computer programs via labor-intensive manual coding is increasingly being replaced by automating machine learning algorithms.57

Supervised machine learning progress has been rapid owing to the availability of vast amounts of training data, which capture valuable and previously unnoticed regularities, often beyond human notice or even comprehension. In this way, tacit knowledge can be codified by creating usable software. These techniques work best when there are large amounts of input data (X) that can be mapped to labeled output data (Y). The machine learning algorithm can then find the relationships (X→Y) and, depending on the application, classify the outputs into categories or make predictions about outcomes. Table 3-1 gives some examples.

Foundation models,58 which include LLMs and other forms of generative AI, are the latest AI breakthrough. Investment in generative AI is a small fraction of total investments in AI but is growing rapidly, and generative AI is already expanding the possibilities of what AI overall can achieve. It is important to note that to date much of the investment in generative AI is concentrated in a handful of highly digitized tech giants and platform companies along with venture capital–financed firms in the United States.

Unlike other technological advances in recent decades that automated many routine physical and cognitive tasks done by humans, generative AI systems will mostly affect cognitive work—both routine tasks and nonroutine tasks. Routine tasks are ones that follow explicit rules and procedures. In contrast, the rules and steps in nonroutine

___________________

55 T. Eloundou, S. Manning, P. Mishkin, and D. Rock, 2023, “GPTs Are GPTs: An Early Look at the Labor Market Impact Potential of Large Language Models,” arXiv preprint, arXiv:2303.10130.

56 E. Brynjolfsson and T. Mitchell, 2017, “What Can Machine Learning Do? Workforce Implications,” Science 358:1530–1534, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aap8062; E.W. Felten, M. Raj, and R. Seamans, 2023, “Occupational Heterogeneity in Exposure to Generative AI,” April 10, http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4414065; E. Felten, M. Raj, and R. Seamans, 2021, “Occupational, Industry, and Geographic Exposure to Artificial Intelligence: A Novel Dataset and Its Potential Uses,” Strategic Management Journal 42(12):2195–2217, https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.3286; and C.B. Frey and M.A. Osborne, 2017, “The Future of Employment: How Susceptible Are Jobs to Computerisation?” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 114:254–280.

57 E. Brynjolfsson and T. Mitchell, 2017, “What Can Machine Learning Do? Workforce Implications,” Science 358:1530–1534, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aap8062.

58 As discussed in Chapter 1, foundation models are an approach for building AI systems in which a machine learning model is initially trained on a large amount of unlabeled data and can then be adapted to many applications. LLMs like GPT and Bard are examples of foundation models, and tools built around LLMs include ChatGPT. LLMs generate new content, making them a form of “generative AI,” along with tools like Midjourney and DALL·E, which create images, and Copilot, which helps coders write software.

TABLE 3-1 Examples of Machine Learning Applications

| Input X | Output Y | Application |

|---|---|---|

| Voice recording | Transcript | Speech recognition |

| Historical market data | Future market data | Trading bots |

| Photograph | Caption | Image tagging |

| Store transaction | Are the transaction details fraudulent? | Fraud detection |

| Purchase | Future purchase | Customer history-based behavior retention |

| Car locations and speed | Traffic flow | Traffic lights |

| Faces | Names | Face recognition |

| Chemical properties | Clinical effectiveness | Drug discovery |

SOURCE: Created based on data from E. Brynjolfsson and A. Mcafee, 2017, “The Business of Artificial Intelligence: What It Can—and Cannot—Do for Your Organization,” Harvard Business Review, July 18, https://hbr.org/2017/07/the-business-of-artificial-intelligence.

tasks cannot be codified. Systems based on foundation models can accomplish a growing number of nonroutine cognitive tasks that used to be done by cognitive workers. These tasks include composing fluent prose based on bullet points, summarizing documents, brainstorming, planning, and translating information from one language to another. These tasks include many tasks in administrative support, engineering services, financial and business operations, management, and sales. Many of these tasks are currently performed by workers with strong educational credentials, including bachelor’s and graduate degrees. People who were relatively immune to previous waves of automation like creative writers, graphic artists, lawyers, doctors, accountants, and even chief executive officers are now being affected. Furthermore, AI’s capabilities continue to evolve rapidly, suggesting that new effects are likely to emerge rapidly.

A useful approach to understanding the effects of these technologies is the task-based approach. Occupations consist of distinct tasks—according to O*NET, typically from 15 to 30 separate tasks. Rather than automating an entire occupation, AI will typically affect only some tasks in each occupation. For instance, applying the task-based approach, Brynjolfsson and colleagues found that of the 950 occupations they studied, there were none in which machine learning “ran the table” and affected all of the tasks, but AI could affect at least some tasks in most occupations.59

As noted above, using this task-based approach, Eloundou and colleagues estimated that “around 80% of the U.S. workforce could have at least 10% of their work

___________________

59 E. Brynjolfsson, T. Mitchell, and D. Rock, 2018, “What Can Machines Learn and What Does It Mean for Occupations and the Economy?” pp. 43–47 in AEA Papers and Proceedings, Vol. 108, American Economic Association.

tasks affected by the introduction of LLMs, while approximately 19% of workers may see at least 50% of their tasks impacted,” using a threshold of a 50 percent reduction in the time required to complete a task while maintaining quality.60 Even when a task is exposed, labor may remain indispensable for that task, even as overall productivity grows. There may be a transition period, with LLMs initially complementing tasks within occupations before automating them over time.61

Overall, Eloundou and colleagues found significant task exposure in occupations and employment in all industries, with wide sectoral heterogeneity and the highest relative exposures in the information processing industries and in hospitals. Manufacturing, agriculture, and mining show lower exposure. In contrast to the results from Acemoglu cited earlier, exposure appears to be uncorrelated with both recent factor productivity growth and labor productivity growth by sector. LLMs and related technologies could improve productivity in health care and education, two huge and perennially lagging productivity sectors. There is also growing evidence that AI can reduce the cost and duration of new drug discovery, another area in need of a productivity boost.

A recent study by Goldman Sachs estimated that generative AI can substitute for humans in about 25 percent of current tasks.62 The estimated effects vary significantly by job type and industry sector. Higher effects are expected in administrative and office support, legal services, business and financial operations, and management and sales. Lower effects are expected in physically intensive professions such as maintenance and construction and in services such as personal care and food and hospitality services. Only some of the tasks of most jobs are exposed to generative AI automation, ranging from jobs with 50 percent or more of the tasks exposed to generative AI automation—like legal services, sales, and business and financial services—to jobs with less than 49 percent of the tasks exposed to AI automation—like production, construction, personal services, and health care. The Goldman Sachs study conjectures that AI is likely to substitute for humans in jobs with high degrees of task exposure and to complement humans in jobs with lower degrees of task exposure.

Recent research by the McKinsey Global Institute (MGI) concludes that generative AI is likely to have the largest impact on four business functions—customer operations, marketing and sales, software engineering, and R&D. Using a detailed analysis of how generative AI could transform these four use cases, MGI estimates that applying generative AI could increase productivity in customer care by between 30 and 45 percent of

___________________

60 T. Eloundou, S. Manning, P. Mishkin, and D. Rock, 2023, “GPTs Are GPTs: An Early Look at the Labor Market Impact Potential of Large Language Models,” arXiv preprint, arXiv:2303.10130.

61 M.-H. Huang and R.T. Rust, 2018, “Artificial Intelligence in Service,” Journal of Service Research 21(2):155–172, https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670517752459.

62 Goldman Sachs, 2023, “Top of Mind: Generative AI: Hype or Truly Transformative?” Goldman Sachs Global Macro Research, Issue 120, July 5, https://www.goldmansachs.com/intelligence/pages/top-of-mind/generative-ai-hype-or-truly-transformative/report.pdf.

current function costs; could increase sales productivity by about 3 to 5 percent of current global sales expenditures; could increase the productivity for marketing between 5 and 15 percent of total marketing spending; could increase the productivity of software engineering from 20 to 45 percent of current annual spending; and could increase productivity in product R&D between 10 percent and 15 percent of overall R&D costs.63

A May 2024 paper by Acemoglu is more pessimistic about the magnitude of impacts of new advances in AI. Using existing estimates of AI exposure and task-level productivity improvements, it projects more modest macroeconomic impacts, with a maximum increase of 0.66 percent in TFP over a decade. The paper further suggests that these estimates might be overstated, as early evidence focuses on easy-to-learn tasks. By contrast, many future impacts will stem from hard-to-learn tasks, which are influenced by numerous context-dependent factors.64

The automotive, finance, and health care sectors are among those most likely to be affected by generative AI. In the automotive sector, generative AI will improve safety and reduce accidents, a central goal of automobile producers; will enable and accelerate the introduction of autonomous vehicles; will personalize vehicles to customer requirements; and will increase the efficiency of costly marketing and advertising functions. In finance, generative AI is building on traditional AI capabilities already adopted for task automation, algorithmic trading and asset management, fraud detection, and personalized services. In health care, prior to the generative AI breakthrough, AI was already affecting administrative services and insurance, diagnosis and treatment, and patient engagement and adherence.65 Generative AI has the potential to affect all parts of health care—providers, payers, pharmaceutical and medical equipment producers, and services and operations.66

Education, parts of health care, and other forms of personal care are productivity laggards compared to the rest of the economy. Many of the tasks in these sectors have lower exposure to AI than tasks in legal and accounting services and financial services. Moreover, many of these tasks require both physical and social interactions with humans. AI could increase productivity in these perennially low productivity sectors and mitigate the Baumol effect. Chapter 5 provides examples of AI productivity enhancements in education.

___________________

63 M. Chui, E. Hazan, R. Roberts, et al., 2023, “The Economic Potential of Generative AI: The Next Productivity Frontier,” McKinsey & Company, June 14, https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/mckinsey-digital/our-insights/the-economic-potential-of-generative-ai-the-next-productivity-frontier.

64 D. Acemoglu, 2024, “The Simple Macroeconomics of AI,” NBER Working Paper No. 32487, May, National Bureau of Economic Research, http://www.nber.org/papers/w32487.

65 T. Davenport and R. Kalakota, 2019, “The Potential for Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare,” Future Healthcare Journal 6(2):94–98.

66 M. Huddle, J. Kellar, K. Srikumar, K. Deepak, and D. Martines, 2023, “Generative AI Will Transform Health Care Sooner Than You Think,” Boston Consulting Group, June 22, https://www.bcg.com/publications/2023/how-generative-ai-is-transforming-health-care-sooner-than-expected.

Last, there is evidence that adoption of earlier AI systems by firms had a significant effect on within-firm worker average productivity growth, adding 2–3 percentage points annually.67 More recent AI systems could have a similar significant effect on average worker productivity over time. But it is dangerous to predict aggregate productivity effects based on case studies. For instance, it took decades for the productivity effects of computers to show up in aggregate growth and productivity.

Factor 2: Productivity Effects in Specific Applications

Even if AI affects many sectors of the economy, the total productivity impact may be limited if it is only a “so-so” technology that barely improves on existing systems—that adds to corporate profits and substitutes for humans without adding much to productivity.68 In a number of case studies, however, the productivity impact has already been quite large. If these cases generalize, that portends well for aggregate productivity growth.

Some of the key effects of generative AI can be observed in a paper about the phased roll-out of an LLM-based system designed to assist thousands of contact center workers.69 The research compared agents who had access to this system with those who did not. The researchers discovered average productivity gains of 14 percent within just a few months (Figure 3-10). Customer satisfaction increased, and an analysis of millions of transcripts revealed a positive shift in sentiment: consumers used more happy words and fewer angry words. Simultaneously, employee turnover decreased among those who used the system. Moreover, managerial roles evolved, with broader spans of control and fewer interventions needed.

Interestingly, the results showed very disparate effects on different types of workers. Productivity increased by more than 35 percent for the newest workers as well as the least skilled workers but showed almost no change for the most experienced and skilled employees.

How did the system achieve these results and change the organization? The key lies in the fact that while earlier types of software required painstaking coding by humans who needed to fully understand the processes they were detailing, machine learning systems like this one can capture tacit knowledge by examining the relationships among inputs and outputs. This opens up many new processes that were previously learned only through on-the-job experience. Specifically, this system analyzed millions of transcripts of customer interactions and identified the common patterns in

___________________

67 Goldman Sachs, 2023, “Top of Mind: Generative AI: Hype or Truly Transformative?” Goldman Sachs Global Macro Research, Issue 120, July 5, https://www.goldmansachs.com/intelligence/pages/top-of-mind/generative-ai-hype-or-truly-transformative/report.pdf.

68 D. Acemoglu and P. Restrepo, 2019, “Automation and New Tasks: How Technology Displaces and Reinstates Labor,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 33(2):3–30, https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.33.2.3.

69 E. Brynjolfsson, D. Li, and L.R. Raymond, 2023, “Generative AI at Work,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. w31161.

SOURCE: E. Brynjolfsson, D. Li, and L.R. Raymond, 2023, “Generative AI at Work,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. w31161, https://arxiv.org/abs/2304.11771v1. CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 DEED.

successful exchanges. These tended to match the skills of the most skilled and experienced workers, so they benefited less than the newer workers. The system’s success can be attributed partly to the company founders’ strategic decision to develop a technology designed to augment workers rather than attempting to create a fully automated replacement.

Other interesting examples of the productivity effects of machine learning systems are medical image recognition and machine translation. A convolutional neural network trained on 129,450 medical images and 2,032 different diseases was able to diagnose different types of cancer at a level that matched or exceeded 21 board-certified dermatologists.70 The authors argue that AI could provide low-cost access to diagnostic care to billions of smartphone users, a dramatic increase in dermatology productivity. AI is also being used in radiology to improve diagnostic performance, help radiologists to prioritize images, and reduce the time it takes to read images. Recent studies have shown improved diagnostic performance with reduced reading times for images with AI in mammography and bone fracture analysis and treatment. Overall reading

___________________

70 A. Esteva, B. Kuprel, R.A. Novoa, et al., 2017, “Dermatologist-Level Classification of Skin Cancer with Deep Neural Networks,” Nature 542(7639):115–118, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature21056.