Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Work (2025)

Chapter: 2 Artificial Intelligence

2

Artificial Intelligence

This chapter describes the technical field of artificial intelligence (AI), including significant recent progress that is likely to impact the workforce. AI is the part of computer science that focuses on producing computer capabilities similar to those usually associated with human intelligence, such as computer vision, speech recognition, natural language understanding, commonsense reasoning, and robots capable of autonomous operation in the physical world. The term “artificial intelligence” was first used 1955, and research in AI has produced steady progress for decades. In early years, researchers attempted to write computer programs manually to perform tasks such as computer vision, speech recognition, and several types of problem solving. In recent decades, the paradigm for developing AI systems has shifted from one of manual programming to machine learning in which programs are instead trained to perform tasks.1 For example, it is extremely difficult to program a computer manually to recognize different types of animals in photos, but with today’s technology it is relatively easy to use machine learning to train such a program by showing it images of different animals, each labeled with the type of animal present. Between 2005 and 2018, this paradigm shift toward training AI programs rather than manually developing them resulted in major advances and new commercial applications with near-human abilities in fields from image classification to speech recognition. More than a decade ago, machine learning capabilities began to accelerate dramatically with a discovery of the power of methods based on neural networks when

___________________

1 E. Brynjolfsson and T. Mitchell, 2017, “What Can Machine Learning Do? Workforce Implications,” Science 358:1530–1534, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aap8062.

supplied with sufficient data and computational resources. Machine learning models referred to as deep neural networks were first applied to numerous pattern recognition and prediction tasks such as speech recognition and medical diagnosis from imagery in dermatology and radiology. The methods showed remarkable abilities and began to show human parity on numerous benchmarks.

Over the past 5 years, between 2018 and 2023, AI has experienced a major new surge of progress resulting in AI systems with truly remarkable capabilities in comparison to what existed in 2018. This advance was due in large part to new innovations in neural networks (e.g., the adoption of a family of neural networks known as “transformers”), and a shift from training AI systems using human-labeled data to instead using unlabeled text, often from the web, allowing vastly larger sets of training data.2 As a result, the development of AI technology, and its impact on the economy and the workforce, is approaching an inflection point. Much of this recent AI progress is owing to the development of large language models (LLMs) such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT, which exhibits abilities to generate text responses to human prompts significantly beyond those of earlier AI systems. For example, ChatGPT can hold conversations in multiple languages about diverse topics, automatically summarize the key points discussed in large text documents, perform a variety of problem-solving tasks, write computer programs, and pass the Advanced Placement (AP) exams in statistics and in biology with scores above the 80th percentile compared to advanced high school students who take these tests. LLMs are one type of generative AI—that is, AI systems capable of generating text, images, or other content based on input user requests.

In parallel with the development of LLMs, AI programs that can generate realistic images from input text descriptions (e.g., “a falcon landing on a camel in an oasis”), realistic sounding voices speaking messages that are input as text, and computer programs that implement some tasks described by text input have also emerged and demonstrated significant progress in recent years. Together, these generative AI models trained on very large data sets and then used to support a variety of tasks are often referred to as “foundation models,” owing to their ability to repurpose and focus on numerous specialized tasks through methods for shaping them to perform better in specific domains with modest amounts of additional engineering investment. For example, methods have been developed, referred to as fine-tuning, that apply domain-specific data to boost the performance of a foundation model for tasks within a target domain.

___________________

2 Producing large training data sets with human-labeled examples is very costly, whereas unlabeled text is freely available on the Internet. For example, creating the ImageNet training data containing 1 million hand-labeled images was a very significant undertaking and led to major advances in computer vision in the early 2010s. In contrast, recent LLMs such as ChatGPT have been trained on roughly 1 trillion sequences of text from the Internet—a data set roughly 1 million times the size of the human-labeled ImageNet data set.

These dramatic advances in generative AI come along with continuing solid progress in other subareas of AI, such as robotics, where, for example, self-driving vehicles are now being tested in multiple U.S. cities, and in the application of machine learning to very large nontextual data sets, leading to advances, for example, in molecular biology and protein folding.

This rapid rate of technical progress in AI is likely to continue in the near term, as companies and governments direct increasing resources into AI research and development, although AI technical experts agree that there is considerable uncertainty about precisely which new capabilities are likely to emerge over the coming years and exactly when they might occur. Already there is much new research directed toward building more powerful LLMs (e.g., systems that will work with video streams in addition to text) and finding new ways of using them (e.g., connecting LLMs to computer programs such as search engines, math calculators, and route planners). The latter includes rich multistep analyses that enable arbitrary files, such as spreadsheets and technical papers, to be input as context, and that assist users with multiple scientific analyses and visualizations. Signs of the economic impact are already visible—for example, Microsoft’s GitHub Copilot is a system that improves productivity of computer programmers by acting as a programming assistant, automatically generating software from text descriptions of what the code should do. In one test, programmers who used Copilot developed software in about half the time required by programmers who did not.3 Beyond productivity, qualitative studies of job satisfaction have demonstrated that tools for assisting engineers are boosting job satisfaction.

Note that Copilot is an example of how AI tools can assist human workers rather than replace them. Of course, if programmers were to become twice as productive and the volume of programming work were to remain constant, only half as many programmers would be needed. However, as discussed in Chapter 1, the situation is more complex than such a simple replacement model would suggest. The total demand for programming work may well increase if increased productivity leads to lower costs per unit of software produced. Whether increased programmer productivity will result in a need for more or fewer programmers depends also on the elasticity in the demand for software. As in many cases, it is easier to predict which tasks AI might assist or automate than it is to predict AI’s final impact on the total demand for labor.

As will be discussed in Chapter 4, although broad forecasts of AI’s effects on total labor demand are eagerly sought by both the public and the press, they are highly speculative, with a generally poor historical track record. One might have anticipated, for example, that the advent of accounting, bookkeeping, payroll, and tax preparation

___________________

3 S. Peng, E. Kalliamvakou, P. Cihon, and M. Demirer, 2023, “The Impact of AI on Developer Productivity: Evidence from GitHub Copilot,” arXiv preprint, arXiv:2302.06590.

software over the past several decades would have eroded employment in accounting, bookkeeping, payroll, and tax preparation services. Indeed, this erosion was confidently predicted by a highly impactful academic study.4 Instead, U.S. employment in this occupational category doubled from 0.6 million to 1.2 million between 1990 and 2024, which is more than twice the growth rate of overall nonfarm employment.5 The most relevant concern for present and future workers is not whether AI will eliminate jobs in net but how it will shape the labor market value of expertise—specifically, whether it will augment the value of the skills and expertise that workers possess (or will acquire) or will instead erode that value by providing cheaper machine substitutes. The answers to such questions are rarely self-evident.

Beyond this point, it might well turn out that the very definition of the job of programming might be changed by systems such as Copilot. Perhaps future programmers working with systems such as Copilot will spend less time writing low-level code and more time designing the higher-level software architecture and functionality, resulting in a shift in required skills for the job and an advancement in the sophistication of artifacts programmers produce.

One interesting property of the new LLM generation of AI is that in contrast to robotics, which involves work in the physical world, LLMs operate in the cognitive world of knowledge work. Furthermore, because LLMs are able to process and then summarize large volumes of text, one of their uses involves advising human decision makers by summarizing information in relevant documents that the decision maker might not have time to read fully. Likewise, the summarization abilities, coupled with now common powers of meeting transcription, enable people to absorb the content from meetings that they cannot attend, freeing them to develop and create. In this role of summarizing and advising, LLMs might operate as assistants to improve the quality of human decision making, although there may well be other cases where LLMs become sufficiently capable that one can trust them to make some decisions themselves. The threshold for entrusting AI to make the decisions in different use cases, as well as the evolving competence of AI systems, will play a key role in determining where AI replaces, versus assists, human decision makers.

Although recent AI progress has been impressive, it is important to note that these new AI systems are still far from perfect. Technical advancements are needed along multiple dimensions. For example, generative models may generate inaccurate yet persuasive output without warning—a problem with reliability sometimes referred to as “hallucination.” The incorrect statements can come amid multiple accurate statements

___________________

4 C.B. Frey and M.A. Osborne, 2017, “The Future of Employment: How Susceptible Are Jobs to Computerisation?” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 114:254–280.

5 On employment in accounting, tax preparation, bookkeeping, and payroll services, see https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1oMKn. On nonfarm employment, see https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1oMKB.

and be offered in a highly confident manner. This problem with reliable output and difficulties with detection of inaccuracies limit the general use of LLM systems in high-stakes decision making such as direct uses in clinical decision support in health care. Furthermore, LLMs’ reasoning and problem-solving abilities are incomplete, and they sometimes fail to draw correct logical conclusions given a collection of input facts. Acceptance of these systems in the workforce will require in many cases that the systems be endowed with the ability to provide well-calibrated confidences and be able to justify or explain their conclusions more correctly. Other challenges limiting their uses include concerns about bias and fairness; caution and testing are required before introducing these systems into society. It is clear that these issues will be critical to widespread adoption. Several AI researchers have published papers documenting these and other shortcomings of today’s AI systems,6 and some have pointed out flaws in benchmark data sets used to evaluate AI system capabilities (e.g., questions used to test AI capabilities might occur nearly verbatim in the vast collection of web text that forms their training data, casting doubt on the use of these questions to measure AI capabilities to reason about novel situations). Despite these real shortcomings in today’s AI systems, recent technical progress does in fact constitute a very significant qualitative advance in AI capabilities. Shortcomings such as hallucinations and biases are being addressed and reduced (although not eliminated) in more recent systems, and additional technical advances over the coming years appear likely to reduce these shortcomings further while adding significant new capabilities.

TECHNICAL PROGRESS IN ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

This section provides a summary of recent advances in AI across multiple areas. Parts of this section are based on the 2023 paper by Bubeck and colleagues, titled “Sparks of Artificial General Intelligence: Early Experiments with GPT-4.”7

Large Language Models

The greatest advances in AI over the past decade have come from advances in neural networks, and the greatest advances in neural networks over the past few years have come from LLMs, such as OpenAI’s GPT-4, Google’s PaLM, and Meta’s LLaMA.

___________________

6 M. Mitchell, 2023, “How Do We Know How Smart AI Systems Are,” Science 381(6654), https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adj5957.

7 S. Bubeck, V. Chandrasekaran, R. Eldan, et al., 2023, “Sparks of Artificial General Intelligence: Early Experiments with GPT-4,” arXiv preprint, arXiv:2303.12712.

A neural network is a network of interconnected computational units, each of whose exact operation is determined by a number of learned numerical parameter values. These learned parameter values are determined by training the neural network on a set of examples, each of which provides an input to the network, and the desired output for that input. For example, to classify images of different skin blemishes as cancerous or noncancerous, a neural network was trained on more than 100,000 images of blemishes, each labeled as cancerous or noncancerous (and if cancerous, the type of cancer).8 During this training process, the numerical parameter values of each computational unit throughout the network are chosen by attempting to best fit these training data (e.g., attempting to produce the desired network output for each input image). Many practical neural networks contain millions of such numerical parameters. In general, training neural networks is very costly, as it requires iteratively tuning and retuning these parameter values. However, once the network is trained, it is much less costly to apply it to a new input example to calculate the corresponding output.

An LLM is a neural network trained to take as input a sequence of text tokens (words, numbers, punctuation) and to predict the next text token. Nearly all of today’s state-of-the-art LLMs use a particular neural network graph structure called the “transformer architecture,” which was first introduced in 2017 by researchers at Google.9 Following the introduction of the transformer architecture, progress in building increasingly capable LLMs has been rapid. Such LLMs are then used as the basis for systems such as ChatGPT (itself based on an LLM called GPT-4), which can conduct conversations with human users by applying next-word prediction repeatedly in order to generate the software’s portion of the conversation.

Although it sounds relatively uninteresting to train a computer to predict the next word in a sentence, LLMs trained with this objective have been found to exhibit surprising capabilities, including capabilities that had not been achieved previously by AI systems. For example, these systems can perform tasks such as

- Produce highly grammatical sentences as output;

- Operate across hundreds of different natural languages;

- Given multipage input documents, summarize these documents, and answer questions about their content;

- Write working computer programs in several computer languages;

- Solve many math word problems;

___________________

8 A. Esteva, B. Kuprel, R. Novoa, et al., 2017, “Dermatologist-Level Classification of Skin Cancer with Deep Neural Networks,” Nature 542:115–118, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature21056.

9 A. Vaswani, N. Shazeer, N. Parmar, et al., 2017, “Attention Is All You Need,” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30.

- Write poetry; and

- Suggest plans to achieve the user’s input goals.

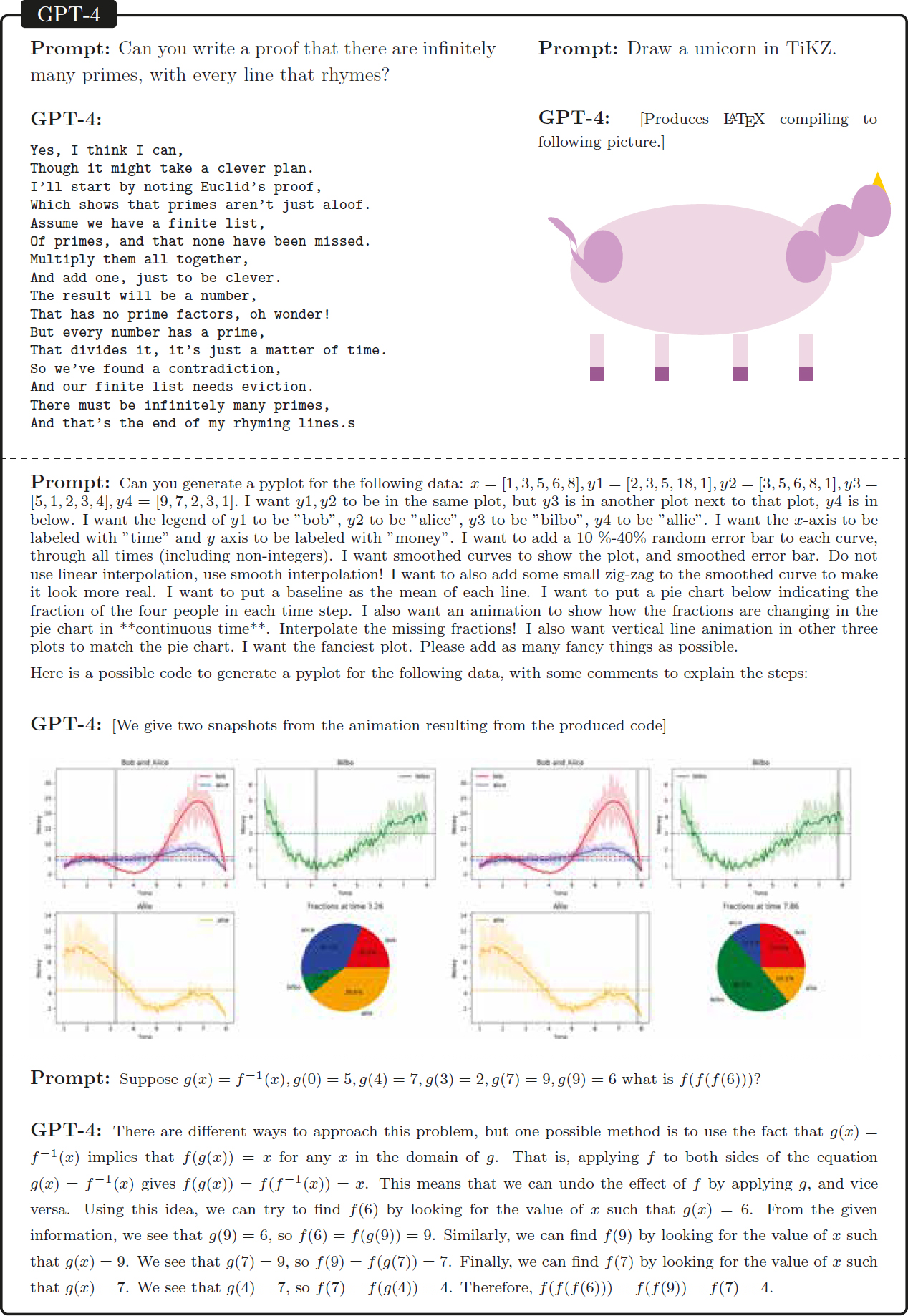

To appreciate the kinds of capabilities of LLMs, consider one of the most capable LLMs as of July 2023, GPT-4, drawing on examples from Bubeck and colleagues.10 Figure 2-1 illustrates some of the diverse tasks that GPT-4 is capable of performing. Notice in the top left of the figure that GPT-4 responds to the prompt “Can you write a proof that there are infinitely many primes, with every line that rhymes?” by writing the proof as a poem. This kind of behavior far outstrips the state of AI from 5 years earlier. One caveat here is that it is likely that a proof of this theorem was included somewhere in the vast set of Internet data used to train GPT-4, although it is highly unlikely that it included the proof written as a poem. The top right of this figure illustrates GPT-4’s ability to draw crude illustrations by writing code in the popular text-formatting language LaTeX. The third example in the figure demonstrates that GPT-4 can create computer code in the popular Python programming language, following complex natural language instructions specifying precisely what the code should do. (In this case, it must display data in a desired form.) At the bottom of this figure, the final example shows the ability of GPT-4 to perform mathematical reasoning, both generating the correct answer and explaining its reasoning steps.

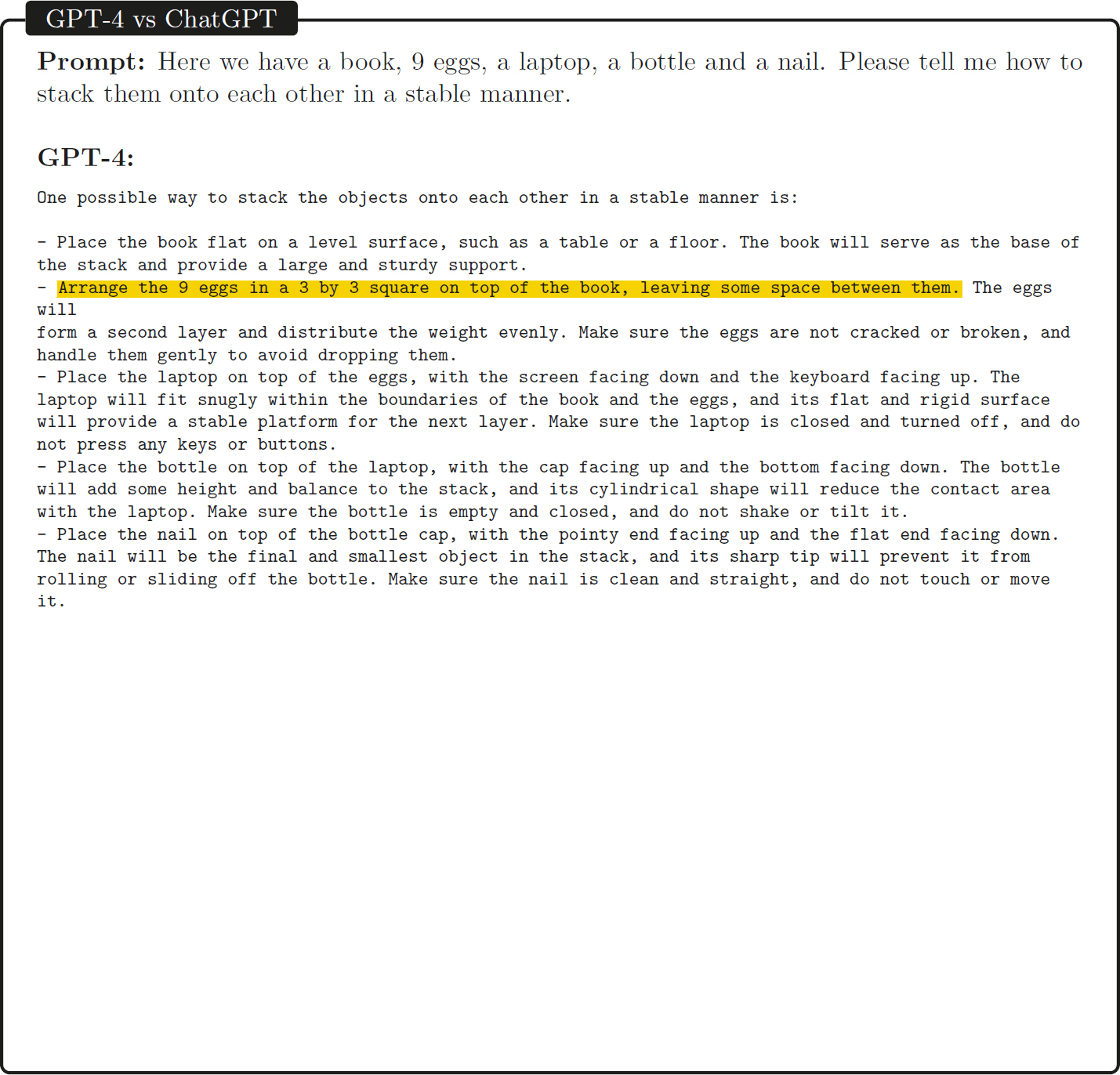

Figure 2-2 provides a further example of the abilities of GPT-4—in this case, reasoning about the physical world. Here, GPT-4 is given the challenging task of determining how to create a stable stack from an unusual collection of objects. As its response illustrates, it answers correctly and somewhat creatively. It is interesting that here it is able to answer correctly about how to assemble this physical structure despite the fact that it has been trained only on data from the Internet and has no direct experience stacking items.

How can such capabilities arise from a system trained simply to predict the next word? Although researchers are still trying to understand the full answer, it is in part owing to the scale of training data used and the form of the neural network trained. These models have been trained on hundreds of billions of words of text taken from the Internet and use transformer networks that contain hundreds of billions of numerical parameters whose values are learned, or tuned, during training to fit these large-scale text data. Specifically, the LLM is trained, for each text snippet, to predict the next token in the sequence. It appears that by forcing the learned network parameters to perform this next-word prediction very well, for hundreds of billions of examples, the network is also forced to learn how to represent the meaning of the input text very well, so that the correct next word can be predicted across a diverse range of possible input sequences.

___________________

10 S. Bubeck, V. Chandrasekaran, R. Eldan, et al., 2023, “Sparks of Artificial General Intelligence: Early Experiments with GPT-4,” arXiv preprint, arXiv:2303.12712.

SOURCE: S. Bubeck, V. Chandrasekaran, R. Eldan, et al., 2023, “Sparks of Artificial General Intelligence: Early Experiments with GPT-4,” ArXiv preprint, arXiv:2303.12712. CC BY 4.0 DEED.

SOURCE: S. Bubeck, V. Chandrasekaran, R. Eldan, et al., 2023, “Sparks of Artificial General Intelligence: Early Experiments with GPT-4,” ArXiv preprint, arXiv:2303.12712. CC BY 4.0 DEED.

As a simple example, consider the input sequence “I parked my car in the….” In order to predict that “garage” is a highly probable next word, the network will have to have learned a representation of text that incorporates the “common sense” that cars are typically parked in garages. Trained LLMs are found to implicitly have much of this kind of commonsense knowledge and, as illustrated in the preceding examples, much more.

To be precise, one technical caveat must be mentioned here: Although the core transformer on which GPT-4 is based has been trained as described earlier (to predict

the next word in a sequence), GPT-4 was subsequently extended by fine-tuning it with human-provided feedback. In particular, after initial training to predict the next word, GPT-4 was given a set of inputs, and it was then applied to produce multiple distinct probable outputs (e.g., “I parked my car in the …” “road.” or “garage.” or “lawn.”). Human labelers then provided feedback regarding which of these outputs was most useful and for “trust and safety” to reduce the likelihood of producing undesirable outputs. These human-labeled data were then used to learn a separate “reward function” that outputs a numerical score characterizing the desirability of any output, and this reward function was then used by a machine learning algorithm known as “reinforcement learning” to learn a final policy for producing output responses. Details are available in the GPT-4 technical report.11 The significance of this use of human feedback is that it provides a mechanism to guide the LLM to produce outputs according to certain human preferences. For example, this can be used to steer the LLM away from biased or offensive outputs and toward outputs that human users find most helpful. Despite this use of human-labeled training data to augment the vastly larger number of unlabeled predict-the-next-word examples, the authors of GPT-4 report that the ability of GPT-4 to pass a variety of exams (e.g., AP exams in chemistry, macroeconomics, and statistics) appears to stem from training on the unlabeled data and that additional training using these human-labeled data does not significantly affect its scores on these and other tests.12

These and other capabilities of GPT-4 and other LLMs have inspired an enormous amount of follow-on research and development. A partial list of recent developments includes the following:

- Multimodal models. Although the first LLMs applied only to text, current efforts involve training on a combination of modalities including text, video, and sound. GPT-4, for example, is already capable of working with images. Google has announced that it is developing a new model, Gemini, which will be trained from the ground up to handle multimodal input/output.

- Plugins. As noted earlier, LLMs make a variety of errors, including factual errors and errors in various types of reasoning such as multiplying large numbers. One way to reduce factual errors is to interface LLMs to search engines, as when Microsoft interfaced GPT-4 to its Bing search engine. This allows the combined system to answer questions more accurately by first searching for relevant web documents and then allowing GPT-4 to read the document before answering the question. Similarly, other plugin software utilities have

___________________

11 OpenAI, 2023, “GPT-4 Technical Report,” arXiv preprint, arXiv:2303.08774.

12 H. Nori, N. King, S. Mayer McKinney, D. Carignan, and E. Horvitz, 2023, “Capabilities of GPT-4 on Medical Challenge Problems,” arXiv preprint, arXiv:2303.13375.

- now been connected to ChatGPT, including utilities such as a numerical calculator (which, assuming the LLM is able to invoke the tool correctly, eliminates mathematical errors) and Wolfram Alpha (which provides various types of factual knowledge and calculations). Significantly, this trend provides a pathway to boost the reliability, accuracy, and depth of knowledge of LLMs in specific domains by leveraging previously developed software. Thus far, correct tool invocation has proven to be a surprisingly hard technical problem.

- Software architectures that use LLMs as submodules. A variety of recent research has explored new types of software architectures for AI assistants that are based on calling LLMs as submodules, or subroutines. For example, LangChain is one popular example of open-source software that enables software developers to combine LLMs including GPT with internal data and internal software applications. AutoGPT is another open-source example that allows building agents that call GPT multiple times to perform different tasks, and that provides functions including file storage and memory, which are missing from bare LLMs. Systems that provide multistep engagements around tasks, such as GPT Code Interpreter, enable users to input technical papers and data files and engage in multiple-step analyses, with explanations of work undertaken by the system on its problem-solving steps along the way to a solution. This trend opens a way for the open-source research community, and other researchers outside the companies developing these large models, to participate in moving the field forward.

- Smaller and/or more specialized LLMs. Given the size of GPT-4 and similar LLMs, which typically have hundreds of billions of parameters and thus take months of supercomputer time to train and cannot be downloaded easily to standard-size computers, there is considerable interest in finding ways to build smaller models with similar capabilities or with strong capabilities in specific domains. For example, in March 2023 Bloomberg announced that it is building an LLM specifically trained on financial data and text, with the intent to use it for financial applications. In the open-source community, there has also been a great deal of activity exploring how to train smaller models. When Meta released its LLaMA LLM, a variety of research teams from various universities built on this by fine-tuning smaller versions of LLaMA using, for example, training data collected by querying Open AI’s GPT LLM. This produced

- 13-billion-parameter models such as Alpaca,13 Vicuna,14 Koala,15 and Orca,16 each of which fine-tuned the 13-billion-parameter version of LLaMA using new data and resulting in stronger performance than the original 13-billion-parameter LLaMA LLM. These open-source efforts show that LLMs can now be trained to approach, although not yet match, the accuracy of the strongest available LLMs, despite being 10 to 100 times smaller, and that large models such as GPT-4 can be used to produce the training data for these smaller models.

The preceding list of ongoing research directions captures only a fraction of the efforts to extend the capabilities of LLMs and AI systems based on them. Technical experts generally agree that further advances should be expected in coming years, but great uncertainty remains about what specific new capabilities future LLMs will exhibit and in what timeframe.

Computer Vision

Computer vision is the branch of AI that deals with perceiving and manipulating image and video data. Research in this area has also advanced significantly over the past decade, in several directions. Computer vision tasks include object recognition (the ability to recognize objects and people in images), object tracking (the ability to track an object such as an individual person from frame to frame in a video stream), computational photography (the ability to improve image capture and preprocessing, such as auto-focus and red-eye removal), medical image analysis (e.g., automatic interpretation of X-ray images), and many other tasks.

One significant step forward in computer vision occurred in 2012, when the annual competition among computer vision systems for recognizing objects in images was suddenly won by a large margin by a new machine learning approach called “deep learning.” In contrast to earlier approaches in which humans designed a set of low-level visual features to represent input images (e.g., features like edges and other local image properties), this new approach allowed the machine learning algorithm using multilayer neural networks to operate directly on the image pixels and discover its own features as part of the training process. Within a few years, the majority of research in computer

___________________

13 R. Taori, I. Gulrajani, T. Zhang, et al., 2023, “Alpaca: A Strong, Replicable Instruction-Following Model,” Stanford Center for Research on Foundation Models, https://crfm.stanford.edu/2023/03/13/alpaca.html.

14 The Vicuna Team, 2023, “Vicuna: An Open-Source Chatbot Impressing GPT-4 with 90% ChatGPT Quality,” March 30, https://lmsys.org/blog/2023-03-30-vicuna.

15 X. Geng, A. Gudibande, H. Liu, et al., 2023, “Koala: A Dialogue Model for Academic Research,” April 3, https://bair.berkeley.edu/blog/2023/04/03/koala.

16 S. Mukherjee, A. Mitra, G. Jawahar, S. Agarwal, H. Palangi, and A. Awadallah, 2023, “Orca: Progressive Learning from Complex Explanation Traces of GPT-4,” arXiv preprint, arXiv:2306.02707.

vision changed to adopt this deep neural network approach. Within a few more years, deep neural networks also led to rapid advances in speech recognition and many other sensory perception problems, and later in the analysis of text as well.

Recent years have produced steady progress in all of these areas of computer vision as well as the commercial adoption of computer vision in a variety of domains. Computer vision based on neural networks is now used to interpret a variety of radiological images, typically providing assistance to human radiologists. Object recognition is widely used to index image libraries (including personal photo libraries), enabling search over images based on the name of a person or object. Progress in self-driving vehicles relies heavily on computer vision and data from light detection and ranging (lidar) sensors to build a map of surrounding roads, pedestrians, obstacles, and vehicles, and to model their current and anticipated future directions of motion. In manufacturing, computer vision methods are widely employed to automate, or partly automate, the inspection of parts and processes.

One particularly active area of progress in computer vision stems from recent progress in generative AI models. Just as LLMs are able to generate text, researchers have now produced generative models that output images given only a text description of the content.

This ability to generate images automatically from text (and, in the other direction, to generate text captions from input images) signals a key technological advance in AI—namely, that the point has been reached where the semantics, or meaning of text, is represented inside the computer in sufficient detail to produce a visual illustration. This stepping-stone of developing amodal (i.e., shared across text and images) meaning representations suggests that future research in AI may be based on systems that handle both images and text simultaneously. The beginning of this trend is already visible, with OpenAI’s GPT-4 accepting images as well as text as input and Google’s Gemini system “created from the ground up” to be multimodal—that is, able to deal with images and videos as well as text.

What are the potential implications of computer vision for the future of work? Computer vision systems are already being used to perform tasks such as inspecting parts, analyzing radiological images, indexing video libraries, and modeling the external world for self-driving vehicles. In some cases, this can result in replacing human workers. For example, computer vision systems that capture license plate numbers as cars pass by, allowing owners to be billed automatically, have made it possible to largely automate the work of toll booth workers. Toll workers are thus being replaced, while some new U.S. jobs are being created by the design, manufacture, installation, and maintenance of computer vision systems. In other cases, computer vision can lead to higher quality or complete deployments of tasks previously performed by people alone—for example,

the relatively low cost and high quality of computer vision for parts inspection leads in some cases to a more complete inspection of parts at multiple stages of manufacture. In yet other cases, the success of computer vision leads to completely new products or services—for example, to automobiles that visually track road lanes to alert drivers who drift out of lane. Predicting the exact impact of computer vision on the workforce is a complex problem, as different applications offer differing opportunities for computer vision to substitute for human labor, assist human labor, or create new products and services.

Robotics

The field of robotics continues to make steady progress as well. Unlike LLMs, which are purely software, or computer vision systems, which are software connected to cameras or similar sensors, robots are composed of complex mechanical systems (with motors, moving parts), various sensors (e.g., vision, touch, torque), and AI software to perform perception and control of the robot. Progress in robotics can therefore require progress in all of these component technologies—not just software.

Areas where robots are increasingly used in practice include the following:

- Assembly and factory automation. For decades, fixed-location, assembly-line robots have been used for machining and assembly. They are increasingly used in automotive and electronics assembly, as well as in industries that must manipulate liquids such as the food and beverage industry and the pharmaceutical industry.

- Movement of warehouse inventory. Unlike assembly-line robots, this application involves mobile robots that move around in engineered spaces such as warehouses. One notable example is the use of Kiva robots by Amazon. Kiva robots navigate Amazon warehouses with the help of barcode stickers on the floor and are used to retrieve items for orders placed through Amazon. These robots bring the items for an order to human workers, who then package them for delivery. Since its initial adoption of Kiva robots, Amazon has continued to add new robotic and computer vision support for its warehouse operations, in the direction of introducing more general-purpose robots that operate in the same space as people and introducing additional uses of computer perception to identify and select packages.

- Self-driving vehicles. This application is under development, and although AI-based driver assistance is in fielded use, fully autonomous driving in arbitrary environments has remained elusive owing to the broad variety of rare cases that must be handled in order to achieve 100 percent autonomous

- driving. For example, Tesla’s commercially available Full Self-Driving Beta is capable of driving autonomously most of the time when on standard U.S. interstate highways, which have few unpredictable moving obstacles such as pedestrians and dogs, but drivers must keep attentive and be prepared to take control. Alphabet’s Waymo and General Motors’ Cruise have already been testing autonomous taxis in limited areas, and in August 2023, California’s Public Utilities Commission granted permission to both to operate autonomous taxis 24×7 throughout San Francisco. Despite difficulties to date in achieving fully autonomous driving, AI-based technology has already facilitated many auto safety features such as lane departure warning, adaptive cruise control, blind spot monitoring, and rear cross traffic alerting. These safety features, as with full self-driving technology, rely heavily on computer perception of surroundings, where great progress has been made. Current bottlenecks include planning and reasoning about how to respond to unanticipated events such as a ladder lying in the road or a construction site that temporarily blocks the view of oncoming traffic.

- Drone delivery. This application, also under development, seeks to provide airborne package deliveries via autonomous drones. In some ways, flying drones autonomously is an easier technical problem than driving cars autonomously, because there are fewer unexpected obstacles to avoid in the air. Several companies—including Amazon, Walmart, and UPS—are currently experimenting with autonomous drone delivery. Drone delivery company Zipline reported in March 2023 that it had completed more than 500,000 drone deliveries, many involving medical supplies in Africa.

Technical progress in robotics has been steady, although progress has not taken place at the rapid rate of progress in natural language processing driven by LLMs. However, there is a significant possibility that future advances in LLMs—especially the further development of multimodal visual-text-audio LLMs—may have a large impact on robotics by integrating the commonsense problem-solving abilities of LLMs with robotic perception and control. Although a burst of progress in robotics is not certain, the potential of future LLMs and other foundation models to accelerate progress in robotics is significant. Progress and widespread deployment in robotics will also require in many cases progress in the mechanical design and mechanical reliability of robots, and progress in sensor and effector technologies, in addition to progress in AI software to control the robot.

DRIVERS OF TECHNICAL PROGRESS IN ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

Several factors have driven and are likely to continue driving AI progress. These include the following:

- Increasing volumes of online data available to train AI systems. Over the past three decades, especially since the spread of the World Wide Web in the 1990s, the volume of online data has exploded. Such data are key to training accurate AI systems using machine learning. For example, hundreds of millions of historical credit card transactions are used to train the AI systems that routinely approve credit card transactions in real time based on their probability of being fraudulent. Importantly, the huge collection of online text found on the World Wide Web and social media platforms forms the backbone of text data used to train modern LLMs. Large collections of video data, such as YouTube, are likely to be key to training future multimodal LLMs.

- Increasing computational power. The past several decades of progress in integrated circuits have produced much faster parallel hardware necessary to support training LLMs and other large AI systems. One type of chip called a graphics processing unit, developed to support video graphics, has been found to provide the kind of parallel matrix computations central to training neural networks and is now widely used for this purpose. Specialized hardware designed specifically for AI is likely to continue this trend. In considering the computational needs for AI systems, it is important to note that training an AI system typically requires several orders of magnitude more computation than applying a trained AI system—one consequence of this fact is that while only a few organizations can afford the cost of training state-of-the-art LLMs, many organizations can afford utilizing these LLMs over the cloud. In the case of open-source models such as Meta’s LLaMA models, it is also possible to download the already-trained models and execute them on local computers. Both Apple and Google are incorporating local execution of LLMs into their mobile phones.

- Algorithmic innovations. A variety of machine learning algorithmic innovations were central to recent AI advances. For example, the advent of deep neural network algorithms around 2010 led to major advances in computer vision and speech recognition over the subsequent decade. More recently, the development of the transformer architecture and the method of training these systems to predict the next word in a sequence was also an important step forward.

- Increasing investments in AI technology. Owing to AI’s economic importance, private and government funding for AI research and development has increased significantly in recent years, especially over the past year or two. Competition among the major technology companies, international cooperation and competition in AI research and development, and investment in AI start-ups by venture capital firms are likely to keep this investment flowing for some time.

Factors that might limit the rate of future AI progress include the following:

- Diminished engagement of universities in developing AI and a potential falloff in graduate training. One important trend over the past decade has been a shift in where the largest AI research advances are being made. Although university researchers led AI development for many decades, openly publishing their most advanced algorithms, in recent years many of the greatest advances have come instead from large companies that have in some cases kept the details of their algorithms a secret. Importantly, the recent development of LLMs has been driven by a handful of large companies with little university involvement, and the AI algorithms that underlie major LLMs including GPT-4 and Gemini remain trade secrets, inhibiting the rate at which new advances can build on current approaches. Given that the development of a state-of-the-art LLM costs at least hundreds of millions of dollars, universities typically cannot participate in this kind of research. It is possible that if universities are unable to compete with research at the handful of well-resourced companies, the number of graduate students learning and developing the latest AI methods might suddenly decrease, thus decreasing the number of skilled researchers graduating as AI experts. Note that (1) it is not clear at present whether this shrinkage will occur, because some governments are considering new ways of providing computing resources to universities for AI research; and (2) it is not clear at this time whether future AI progress will stem solely from developing even bigger and more expensive models, or whether the open-source research community will find ways of building highly capable AI systems that are much smaller and less resource-intensive.

- Equity of access. Relatedly, much of the most advanced AI technology and the computing and data to develop it are primarily in the hands of a small number of large technology companies or smaller companies, many of which have ties to the large technology companies. Partially offsetting this has been the availability of open-source models, some of which were released by the technology companies.

- Limits in access to ever-larger training data sets. LLM development so far has followed a scaling curve, where each successive generation of increasingly capable LLMs is larger (i.e., has more trained parameters) and is based on a larger set of training data. It has been estimated that current state-of-the-art LLMs are based on roughly 1 trillion training examples of text snippets gathered from the Internet. If this scaling curve continues to hold, even larger data sets will be needed to make further advances. However, some relevant data sets, such as Google’s YouTube collection of video data, are privately held and not widely accessible. Such limitations on access to large privately held data sets may reduce the number of organizations that can innovate at the frontier of the field. Furthermore, some Internet sources are now raising questions about how their data can be used. For example, Getty Images, which hosts and sells images over the Internet, has sued Stable Diffusion, one of the developers of generative AI software trained to generate images from text descriptions, for copyright infringement associated with the use of Getty’s images for training.

- Limits on access to sufficient computing capacity. Training larger models requires more computing capacity, which in turn requires more high-end semiconductors, expanded or new data centers, and additional electrical power. All these are capital-intensive and push up against industrial capacity or regulatory constraints. Physical constraints on the smallest possible size for semiconductor transistors may in the future also constrain the ability to provide faster, more energy-efficient computation with each new generation of computing hardware.

- Government regulations. Governments in many countries are now considering potential regulations that would constrain the development or deployment of various types of AI systems. For example, Italy initially banned the use of ChatGPT shortly after its release because of concerns about ChatGPT’s collection and use of user data as well as its failure to prevent underage users from accessing inappropriate content. More broadly, many governments are now taking a fresh look at AI, its potential impacts on society, and what types of norms are desired to guide its development and deployment. In most cases, it is likely that regulation of AI will occur at the level of individual applications (e.g., regulation of self-driving cars by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration and state motor vehicle agencies or regulation of AI-based medical diagnosis systems by the Food and Drug Administration). However, there might also be regulations of more general AI technologies such as LLMs (e.g., to require that they report on their factual accuracy in various topics, or whether they can inadvertently output part of the text or images they were

- trained on). The discussion of how governments should guide AI development is in early stages and is likely to continue for years, providing some uncertainty around commercial uses of AI.

- Social acceptability. To be socially acceptable, AI systems must align with the norms of society. For example, researchers and developers have worked over the past 5 years to reduce disparities in the accuracy of face recognition technology across different phenotypes that arose from biases in the demographic makeup of the training data sets. More broadly, bias, fairness, trust, and accountability of AI systems will need to be addressed as part of the process of introducing them into society. Note that the threshold on AI capabilities that result in social acceptability can vary widely across different applications, along with different costs of error: an error by ChatGPT might result in an incorrect answer, whereas an error by an AI-based delivery drone might result in crashing into a nearby pedestrian, and an error in an AI-based military system might have dramatically more costly impacts and corresponding public backlash.

FINAL OBSERVATIONS

AI technology appears to be at an inflection point, where rapid technical progress has occurred over the past few years and seems likely to continue for some time. Its impact on the workforce and on productivity is likely to be significant, with LLMs offering new opportunities for enhancing worker productivity across many industries, from health care to education to journalism to scientific research itself. Beyond LLMs, there is also substantial technical progress in other areas of AI, including robotics, perception, and machine learning applied to large, structured data sets. There is a significant chance that progress in these other AI areas may accelerate in the near future, as researchers explore how to use LLMs to impact these areas and if the anticipated generalization of LLMs to multimodal generative models occurs.

Exactly which work tasks and therefore which jobs will be most impacted remains to be seen. It is likely that AI will assist workers in some cases (e.g., assist doctors by providing a second opinion on medical diagnoses) and replace workers in other cases (e.g., just as computer vision algorithms have been instrumental in replacing toll booth operators with computers). Even in cases where AI assists and increases productivity of workers, it can be unclear whether demand for those workers will increase or decrease; improved productivity can lead to reduced prices and therefore increased demand, so that the final impacts depend also on elasticities in the demand for the goods that these

workers produce. One must also be careful in extrapolating from the performance of recent AI systems on benchmark tests (e.g., passing the Law School Admission Test [LSAT]) predictions about which jobs an AI system might be able to perform (e.g., successful lawyers have many additional skills that are not tested by the LSAT).

Although current generative AI technology is imperfect—it can output “hallucinated” claims and can provide faulty solutions to problems it is asked to solve—it is already of clear use in providing assistance to programmers, authors, educators, and many other kinds of knowledge workers. There is much uncertainty about how the technology will develop further but little doubt that it will advance. There are already areas where it is significantly improving productivity (e.g., software development), and the burst of new venture capital in this area ensures that there will be a burst of new exploration into how to take advantage of this technology. The bottom line is that while substantial ongoing progress should be expected over the coming years, it is difficult to predict precisely which technical advances AI is likely to achieve next and on what timetable. To prepare, strategies and policies must be able to accommodate a variety of technology futures with differing timetables and technical advances.