Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Work (2025)

Chapter: 4 Artificial Intelligence and the Workforce

4

Artificial Intelligence and the Workforce

Despite widespread popular and academic concern that artificial intelligence (AI) and robotics are ushering in a jobless future, the industrialized world is currently awash in jobs.1 Three years after the onset of the deepest recession since the Great Depression, the U.S. unemployment rate has returned to its historically low prepandemic level of 3.5 percent, and, similarly, labor force participation and employment-to-population rates have nearly fully recovered.2 A comparable situation is unfolding across many industrialized countries. At the end of 2022, average Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)-wide employment and labor force participation rates were at their highest recorded levels, with half of all OECD countries exceeding previous high-water marks on both metrics.3

It is difficult to predict how unemployment rates may change in the years to come. The Congressional Budget Office projects that the U.S. population will grow at a glacial rate of 0.3 percent between 2023 and 2053, one-third the pace prevailing during the

___________________

1 On the possibility of a jobless future, see J. Rifkin, 1995, The End of Work: The Decline of the Global Labor Force and the Dawn of the Post-Market Era, GP Putnam’s Sons; M.R. Ford, 1995, The Rise of the Robots: Technology and the Threat of Mass Unemployment, Basic Books; C.B. Frey and M.A. Osborne, 2017, “The Future of Employment: How Susceptible Are Jobs to Computerisation?” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 114:254–280; D. Susskind, 2020, A World Without Work: Technology, Automation and How We Should Respond, Penguin UK; A. Korinek and M. Juelfs, 2022, “Preparing for the (Non-Existent?) Future of Work,” NBER Working Paper No. w30172, June.

2 U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2023, “BLS Employment Situation Summary, April 7, 2023,” https://www.bls.gov/news.release/empsit.nr0.htm.

3 OECD, 2023, “Labour Market Situation: OECD Employment and Labour Force Participation Rates Reach Record Highs in the Fourth Quarter of 2022, April, https://www.oecd.org/sdd/labour-stats/labour-market-situation-oecd-updated-april-2023.htm. Note that these labor force participation and employment-to-population series commenced in 2005 and 2008, respectively, so the historical comparison window is comparatively short.

prior four decades and below any sustained growth rate seen since the Census Bureau began tracking these statistics in 1900.4 This backdrop of mounting labor scarcity would seem to diminish prospects for widespread technological unemployment.

Although broad forecasts of AI’s effects on total labor demand are generated regularly by consultancies and are reported credulously by the press, such forecasts are highly speculative. An extraordinarily highly cited 2017 academic study by Frey and Osborne projected that “47% of total U.S. employment is in the high risk category” for automation, where “high probability occupations are likely to be substituted by computer capital relatively soon.”5 No such occupational apocalypse has come to pass. To take a specific example, one might have anticipated that the advent of accounting, bookkeeping, payroll, and tax preparation software over the past several decades would have eroded employment in accounting, bookkeeping, payroll, and tax preparation services. Indeed, Frey and Osborne placed the probability of computerization of each of these four categories at 97 percent or above. Instead, U.S. employment in this group of occupations grew by 19 percent in the 7 years since the publication of Frey and Osborne’s paper and doubled between 1990 and 2024 from 0.6 million to 1.2 million workers (more than twice the growth rate of overall nonfarm employment).6

A key theme of this report, and this chapter in particular, is that the most relevant concern for present and future workers is not whether AI will eliminate jobs in net but rather how it will shape the labor market value of expertise—specifically, whether it will augment the value of the skills and expertise that workers possess (or will acquire) or instead erode that value by providing cheaper machine substitutes. The most pernicious prospect that AI and robotics hold for the labor market is that they could substantially erode the value of human expertise—certainly within specific domains and perhaps more broadly. Shifts in the market value of human expertise are where the labor market effects of technical change generally, and AI specifically, may first be seen.

___________________

4 Congressional Budget Office, 2023, “The Demographic Outlook: 2023–2053,” January, www.cbo.gov/publication/58612; W.S. Frey, 2021, “U.S. Population Growth Has Nearly Flatlined, New Census Data Shows,” Brookings Institution, December, https://www.brookings.edu/research/u-s-population-growth-has-nearly-flatlined-new-census-data-shows. The United States is on a relatively favorable trajectory. The United Nations projects that most industrialized countries will commence population decline during the 21st century. And populations are already falling in multiple continental European countries as well as in Japan and China. The United Nations report states, “Whereas the populations of Australia and New Zealand, Northern Africa and Western Asia, and Oceania (excluding Australia and New Zealand) are expected to experience slower, but still positive, growth through the end of the century, the populations of Eastern and South-Eastern Asia, Central and Southern Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean, and Europe and Northern America are projected to reach their peak size and to begin to decline before 2100.” See United Nations: Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2022, “World Population Prospects 2022,” https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/wpp2022_summary_of_results.pdf; and EuroNews with AFP, 2023, “The Countries Where Population Is Declining,” EuroNews, January 20, https://www.euronews.com/2023/01/17/the-countries-where-population-is-declining.

5 C.B. Frey and M.A. Osborne, 2017, “The Future of Employment: How Susceptible Are Jobs to Computerisation?” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 114:254–280.

6 On employment in accounting, tax preparation, bookkeeping, and payroll services, see https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1oMKn. On nonfarm employment, see https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1oMKB.

To define terms, “expertise” denotes a specific body of knowledge or competency required to accomplish a particular objective—for example, baking a loaf of bread, taking vital signs, or coding an app (Box 4-1).7 Human expertise commands a market premium to the degree that it is, first, necessary for accomplishing valuable objectives and, second, not possessed by most people. This scarcity may arise because the relevant skills are costly or time-intensive to acquire (e.g., training to become a surgeon, pilot, or cabinetmaker); certain talents are intrinsically rare (e.g., gifted athletes, musicians, or mathematicians); market conditions create temporary scarcity (e.g., surging demand for COBOL programmers during the run-up to Y2K); or legal and regulatory barriers limit the number of trained or certified workers (e.g., residency training in medical specialties such as endocrinology).

BOX 4-1 Defining Concepts Related to Expertise

The following are other related terms frequently used in discussions of technology and labor markets:

- Skill formally means the ability to do something well. Economists often use skill in a unidimensional sense: a worker is low-skilled, mid-skilled, or high-skilled. This is too simplistic, however: one can be highly skilled in carpentry and unskilled in software development, or vice versa. But making this distinction requires specifying what someone invoking the term is “skilled in,” which means specifying what expertise the worker possesses. In that case, the term “skill” adds little value, whereas the term “expertise” unambiguously refers to skill in a specific domain.

- Education and credentials are means of acquiring and certifying expertise. But expertise is often acquired through on-the-job experience and noncredentialed training, so education and credentials pertain to only a subset of the expertise that workers possess.

- Occupations provide a useful shorthand to denote broad categories of work, often conveying both specific skill sets and formal certification (e.g., attorney, master plumber). At the same time, occupational categories are not as crisp as they sometimes appear. One reason is that the set of specific duties (“tasks”) in occupations changes over time, even without any change in occupational titles. Prior to the advent of office computing, for example, secretarial duties typically included answering phones, taking shorthand, filing papers, and typing. Aside from typing, contemporary clerical workers do few of these traditional tasks, but they increasingly do complex technical and organizational tasks like expense accounting and event planning. A second reason is that the set of occupational categories evolves and expands as technologies, tastes, and demographics change. There were, for example, essentially no

___________________

7 Many dictionaries define expertise as expert skill or knowledge in a particular field—which is essentially tautological. For example, see https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/expertise, where expertise is defined as “the skill of an expert.”

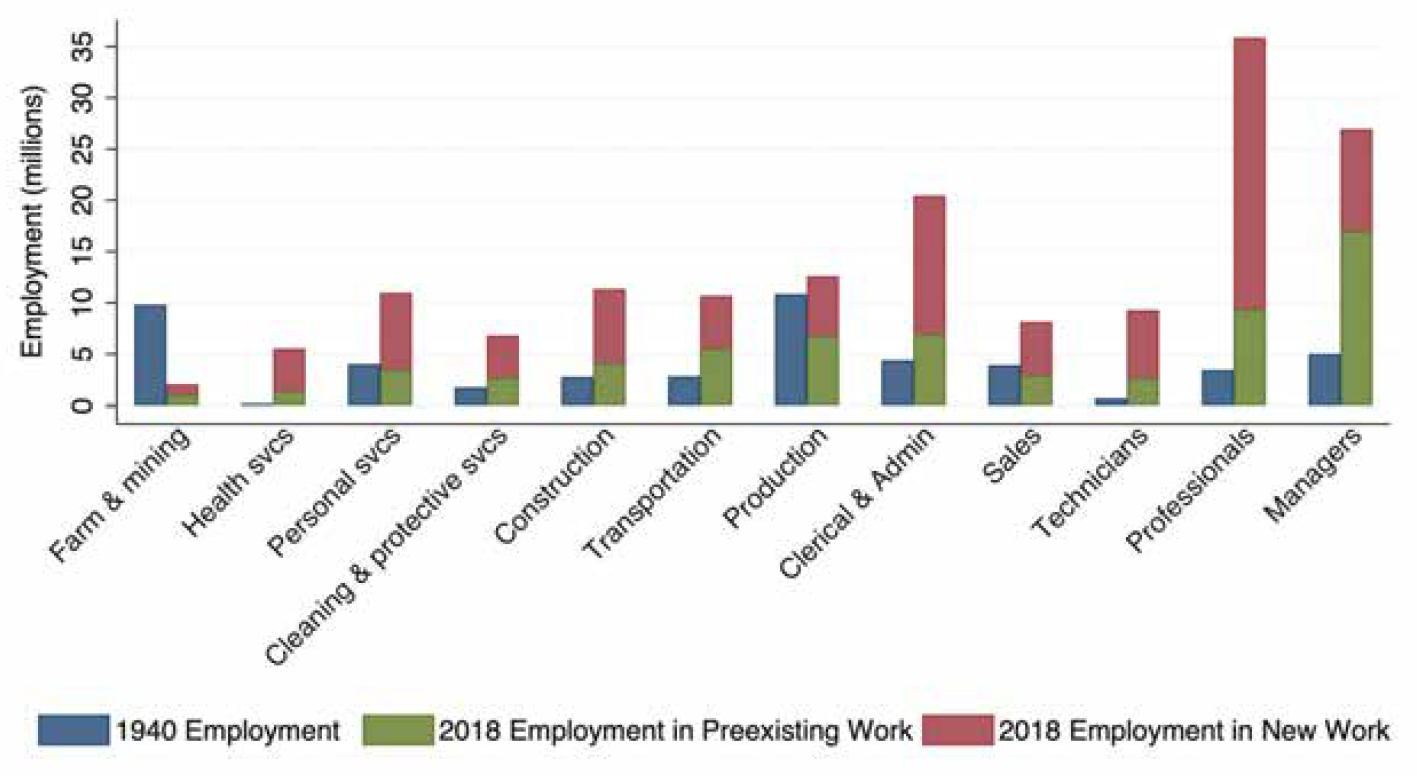

- software developers in the United States before the advent of commercial computing in the 1950s, yet at present there are more than 1.5 million.a Autor and colleagues estimate that the majority of current employment (more than 60 percent) is currently found in new job specialties introduced since 1940.b This chapter uses dozens of occupational examples for illustrative purposes, while recognizing that the expertise required by specific occupations is not static and that new occupations come into existence as new forms of expertise gain relevance.

- Tasks, in economic parlance, are the constituent building blocks of work: workers apply skills to accomplish tasks that produce desired outputs. A job may comprise dozens or hundreds of tasks, depending on how broadly or narrowly tasks are defined. A burgeoning economic literature uses the concept of tasks to describe the interplay between technological change, occupational structure, and skill demands.c The concepts of tasks and expertise are closely related; one can think of tasks as checklists of items to be accomplished (the “what”), while expertise is the know-how required to accomplish those items on the list (“the how”).

- Routine tasks, as used in economics literature, are physically or cognitively repetitive tasks that follow tightly scripted codifiable procedures.d For the purposes of this report, one can equate “mass expertise” with the ability to execute routine tasks. The term “expertise” is used throughout this chapter to distinguish different domains of expertise that do not map tightly to the routine/nonroutine distinction, including artisanal expertise, elite expertise, and translational expertise.

- Automation refers to technological advances that facilitate the substitution of capital for labor at a widening range of tasks or productive processes. Concretely, when a task that was formerly done by workers is delegated to machines, that task is automated.

- Augmentation is a case where a technology enables workers to work more effectively, perform higher-quality work, or accomplish previously infeasible tasks.

__________________

a See U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2023, “Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics: 15-1252 Software Developers,” https://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes151252.htm.

b D. Autor, C.M. Chin, A. Salomons, and B. Seegmiller, 2024, “New Frontiers: The Origins and Content of New Work,” 1940–2018, Quarterly Journal of Economics 139(3):1399–1465, https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjae008.

c See, among other sources, D.H. Autor, F. Levy, and R.J. Murnane, 2003, “The Skill Content of Recent Technological Change: An Empirical Exploration,”The Quarterly Journal of Economics 118(4):1279–1333; F. Levy and R.J. Murnane, 2005, The New Division of Labor, Princeton University Press; D. Acemoglu and D. Autor, 2011, “Skills, Tasks and Technologies: Implications for Employment and Earnings,” pp. 1043–1171 in Handbook of Labor Economics, Vol. 4, Elsevier; and D. Acemoglu and P. Restrepo, 2019, “Automation and New Tasks: How Technology Displaces and Reinstates Labor,”Journal of Economic Perspectives 33(2):3–30.

d This terminology originates in D.H. Autor, F. Levy, and R.J. Murnane, 2003, “The Skill Content of Recent Technological Change: An Empirical Exploration,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 118(4):1279–1333.

Much of the value of labor in industrialized economies derives from the scarcity of expertise rather than from the scarcity of workers per se. Consider, for example, the jobs of air traffic controller and crossing guard. Both make rapid-fire, life-or-death decisions to avert collisions between vehicles, passengers, and bystanders. Despite their fundamental similarities, the median annual pay of air traffic controllers in 2021 ($131,000) was more than four times the corresponding remuneration for crossing guards ($31,500). The key difference separating these jobs is expertise. In most of the United States, working as a crossing guard requires no formal training or certification. Conversely, the job of air traffic controller requires an associate’s or bachelor’s degree in air traffic control complemented by several years of on-the-job apprenticeship.8 These training requirements potentially give rise to scarcity. If an unexpectedly urgent need arose for crossing guards, most air traffic controllers could presumably fill these roles. If an urgent need for air traffic controllers arose, the reverse would not be true.9

Jobs for which mass expertise suffices—such as table-waiting, cleaning and janitorial services, manual labor, and (even) child care—tend to pay poorly, not just in the United States but in all industrialized countries.10 The low pay in these jobs does not reflect a lack of intrinsic value of the services they provide but rather the abundance of workers who are able to do this work.11

Expertise is often acquired through formal education, but the two are not synonymous. Much expertise is acquired through training and experience rather than through schooling. Many occupations in the skilled trades—electrical work, plumbing, heating and cooling, construction, manufacturing production, and so on—do not require formal education beyond post-secondary schooling but are mastered through intensive apprenticeships. Certification for many health vocations—such as dental hygienists, magnetic resonance imaging technologists, and diagnostic medical sonographers—requires an associate’s degree but not a bachelor’s degree. All of these occupations (trades workers,

___________________

8 On crossing guards, see https://www.bls.gov/ooh/about/data-for-occupations-not-covered-in-detail.htm. On air traffic controllers, see https://www.bls.gov/ooh/transportation-and-material-moving/air-traffic-controllers.htm.

9 The fact that expertise is both scarce and necessary to produce a good or service does not guarantee that this expertise will be highly rewarded. The product or service enabled by this expertise must also have significant market value (e.g., expertise in slide rule mathematics is no basis for a career). But occupations that require little expertise are poorly paid as a rule.

10 G. Mason and W. Salverda, 2010, “Low Pay, Working Conditions, and Living Standards,” pp. 35–90 in Low-Wage Work in the Wealthy World, J. Gautié and J. Schmitt, eds., Russell Sage Foundation, http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7758/9781610446303.6.

11 That does not mean the wage will be zero; workers can choose not to work at all. But wage levels in jobs that require only generic skill sets will not depend primarily on the supply of suitably trained workers but rather on the set of alternative options available to workers with generic skills, a point that goes back to W.J. Baumol, 1967, “Macroeconomics of Unbalanced Growth: The Anatomy of Urban Crisis,” The American Economic Review 57(3):415–426. Provided that workers are necessary to perform these generic work tasks, and that consumers do not find non-labor-using substitutes for them or choose to forego these services altogether, earnings in this type of work will tend to rise with societal incomes. Thus, as Baumol observed, earnings of hair stylists, while typically low, have roughly kept pace with overall economic growth.

health technicians) are relatively well paid, reflecting the expertise they require.12 Expertise does not by itself guarantee high pay, of course; the product or service enabled by this expertise must also have significant market value. For this reason, expertise in data science is a sound basis for a wide range of careers, whereas expertise in historical baseball statistics is not.

The objective of this chapter is to assess the implications of rapid advances in AI for the nature of work and the jobs available to workers. The chapter is framed around the demand for expertise because AI is most likely to impact the labor market profoundly by reshaping this demand. The chapter addresses three central questions:

- Substitution: What expertise is likely to be substituted or made obsolete?

- Complementarity: What expertise is likely to be augmented or newly demanded?

- Transition: How feasible will it be for workers to acquire newly valuable expertise?

As is evident, none of these questions directly concern the impact of AI on aggregate employment or unemployment. However, there is ample reason to believe that AI, at least initially, will affect the value of expertise in a multitude of dimensions, and this will be consequential for worker welfare.

Although this report focuses on the United States, similar lessons likely apply to many other industrialized countries—though not necessarily to low- and middle-income countries. One topic on which this chapter will not focus is the demand for AI developers specifically—that is, people who build AI systems. Building AI systems is expert work, of course, and it is reasonable to expect there to be much more of it. But it will not be a large part of overall employment. Consider the example of software developers: Despite decades of sustained growth in investment in computer technology, slightly less than 1 percent of the U.S. workforce is currently employed in software development.13 If this fraction were to double to 2 percent, this would still comprise a smaller share of the workforce than is currently employed as fast food and counter workers.14

Before applying the expertise framework to assess the potential labor market impacts of AI, it is first used to interpret the labor market impacts of the two preceding technological revolutions: the Industrial Revolution and the computer revolution. This framing will both put AI in context with earlier technological eras and demonstrate that

___________________

12 These examples are drawn from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2024, “Occupational Outlook Handbook,” https://www.bls.gov/ooh.

13 As noted earlier, employment in software development was 1.53 million in May 2022 (see https://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes151252.htm), whereas overall U.S. employment was 158.3 million in June 2022 (see Summary Table A of “News Release: The Employment Situation—July 2023,” USDL-23-1689, https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/empsit.pdf).

14 U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2023, “Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics: 35-3023 Fast Food and Counter Workers,” https://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes353023.htm.

the lens of expertise brings key elements into focus across multiple eras of economic history. The chapter begins explaining how technological change simultaneously erodes and augments demand for expertise.

Alongside highlighting these potential employment consequences, the final section of this chapter considers other nonemployment risks arising from the widespread adoption of AI including algorithmic fairness and discrimination, worker surveillance and privacy, and issues around the ownership of creative output and intellectual property.

THE ROLE OF TECHNOLOGY IN ERODING AND AUGMENTING DEMAND FOR EXPERTISE

The term “expertise” refers to capacities that reside in people. Yet, the value of expertise is often inseparable from the tools and technologies that are used by experts. For example, it is self-evident that the tools used by air traffic controllers enhance rather than erode the value of their expert knowledge: absent radar, the Global Positioning System (GPS), and two-way radios, air traffic controllers could do little more than stare at the sky. Similarly, the expertise of plumbers, electricians, and medical technicians would be less valuable—and in some cases irrelevant—absent the tools with which that expertise is applied. The principle is a general one: tools often augment the value of expertise by increasing workers’ capabilities and conserving their time.

But not all technologies augment the value of expertise; some render it superfluous. For example, the market value of taxi drivers’ exhaustive and painstakingly acquired knowledge of the streets and alleys of London was diminished when GPS-enabled ride-hailing apps made that expertise widely available through smartphones. Although there are currently as many London cabbies as ever, their earnings dropped by about 10 percent when Uber entered the market.15 Similarly, the roll-out of an AI-based taxi-routing program in Yokohama, Japan, erased the routing advantage of expert versus novice drivers, largely eliminating the value of expertise.16 In the foreseeable future, the job of air traffic control may be handled primarily by AI, potentially eroding the earnings potential of air traffic controllers. Where technology eliminates the need for human expertise, this generally yields efficiency gains and reduces costs for consumers and

___________________

15 T. Berger, C. Chen, and C.B. Frey, 2018, “Drivers of Disruption? Estimating the Uber Effect,” European Economic Review 110:197–210. Consistent with falling barriers to expertise, the number of self-employed drivers who did not have the traditional London taxi credential rose steeply.

16 K. Kanazawa, D. Kawaguchi, H. Shigeoka, and Y. Watanabe, 2022, “AI, Skill, and Productivity: The Case of Taxi Drivers,” NBER Working Paper No. w30612, National Bureau of Economic Research.

businesses. But this will in many cases lessen the earnings and employment prospects of workers whose expert skills are made less scarce.17

In reality, a stream of technological advances—from automatic transmissions to tax preparation software—continuously erodes the value of expertise by simplifying and automating formerly expert tasks. These technologies are effective: the expertise required to perform simple bookkeeping calculations, for example, was once highly coveted and handsomely remunerated but is now abundantly supplied, is heavily automated, and commands almost no skill premium.18

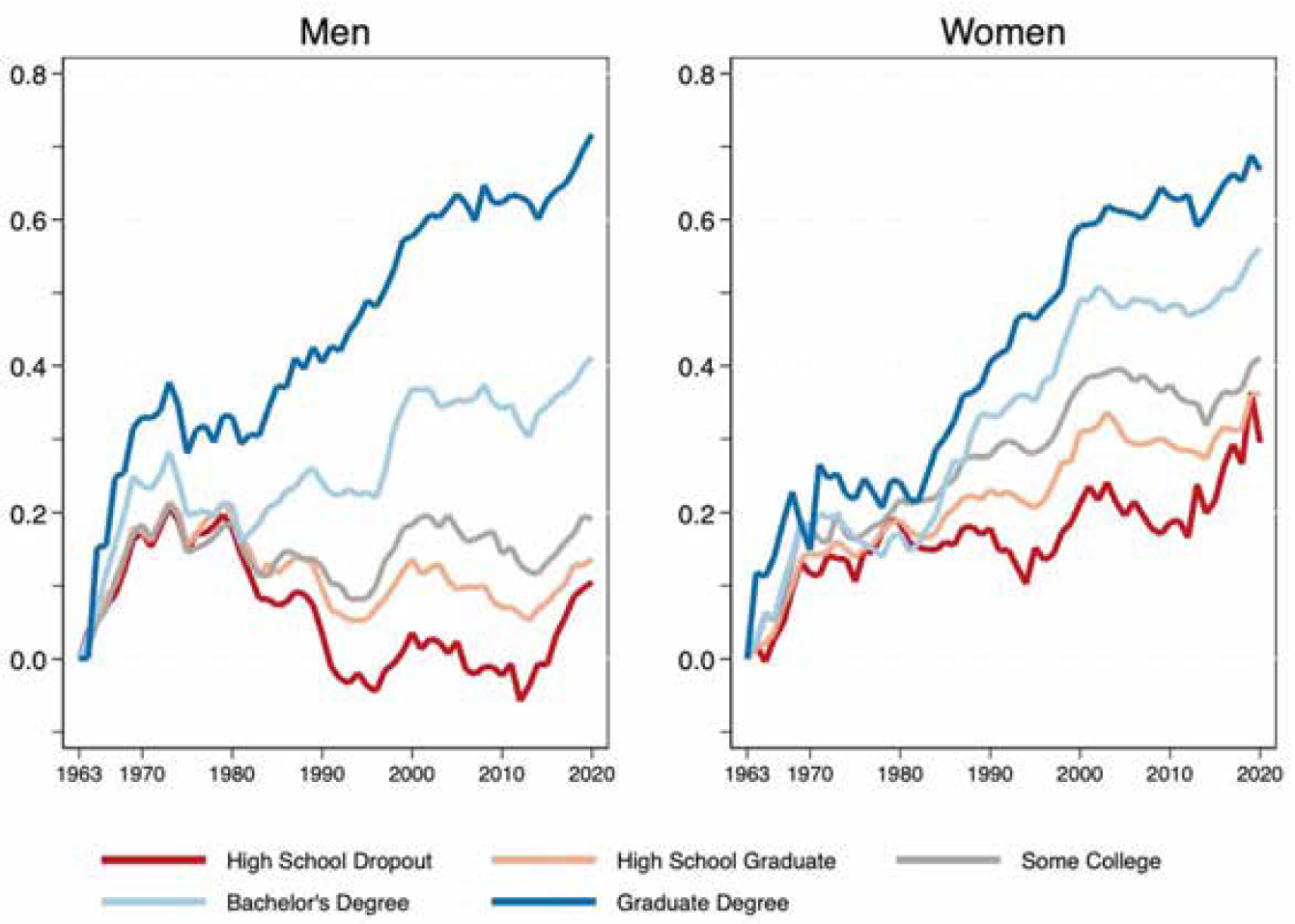

One can see this phenomenon writ large in the U.S. labor market, as shown in Figure 4-1. Despite substantial economic growth over the past four decades, real wages of noncollege workers19 (especially noncollege men) fell steeply from approximately 1980 to 2010 as these workers were displaced from skilled manufacturing and mid-level administrative jobs into generic personal service positions requiring little formal expertise.20

Yet, despite ongoing technological advances that simplify and automate formerly expert work, the return to formal skills—one form of expertise—has been rising for decades. Why has the expertise-commodifying effect of innovation not overwhelmed its augmenting effect? This extinction of expertise—or, more precisely, of its market value—would very likely occur were it not for a central countervailing force: the domain of expertise is continually expanding. Many of the most highly paid jobs in industrialized economies—oncologists, software engineers, patent lawyers, therapists, movie stars—did not exist until specific technological or social innovations created a need for them. Prior to the era of air transport, for example, there was neither a market demand for nor supply of air traffic controller skills. Less than 1 year ago, the job of “prompt engineering”—crafting text queries for chatbots that produce optimal outputs—was essentially nonexistent. It is now in high demand.21

Very few occupations are entirely eliminated by automation (though the occupation of elevator operator serves as the exception that proves the rule).22 But some

___________________

17 R.E. Susskind and D. Susskind, 2015, The Future of the Professions: How Technology Will Transform the Work of Human Experts, Oxford University Press.

18 C. Goldin and L.F. Katz, 1995, “The Decline of Non-Competing Groups: Changes in the Premium to Education, 1890 to 1940,” NBER Working Paper No. 5202.

19 That is, workers with less than a bachelor’s degree.

20 Only in the past decade have earnings of noncollege men regained most of the ground that they lost after 1980. Real earnings declines were, fortunately, shallower and not as enduring among noncollege women. See D. Autor and D. Dorn, 2013, “The Growth of Low-Skill Service Jobs and the Polarization of the U.S. Labor Market,” American Economic Review 103(5):1553–1597; D. Autor, 2019, “Work of the Past, Work of the Future,” AEA Papers and Proceedings 109:1–32; and D. Acemoglu and P. Restrepo, 2022, “Tasks, Automation, and the Rise in U.S. Wage Inequality,” Econometrica 90(5):1973–2016.

21 A. Mok, 2023, “‘Prompt Engineering’ Is One of the Hottest Jobs in Generative AI. Here’s How It Works,” Business Insider, March 1, https://www.businessinsider.com/prompt-engineering-ai-chatgpt-jobs-explained-2023-3; and Wikipedia, 2023, “Prompt Engineer,” Wikimedia Foundation, March 10, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prompt_engineering.

22 Only one occupation has been fully automated in the post-war period—elevator operators. See E. Bessen, 2016, “How Computer Automation Affects Occupations: Technology, Jobs, and Skills,” Boston University School of Law, Law and Economics Research Paper No. 15-49, October 3, http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2690435.

SOURCE: D. Autor, 2019, “Work of the Past, Work of the Future,” AEA Papers and Proceedings 109:1–32, https://doi.org/10.1257/pandp.20191110. Copyright American Economic Association; reproduced with permission of the AEA Papers and Proceedings.

occupations shrink to near insignificance in the face of technological shifts, and those that remain may be distinct from what preceded them. Between 1920 and 1940, automation of the switchboard operator occupation, one of the most common occupations for American women, resulted in significant displacement, with a small remaining core of operators who performed high-level services.23 In the metropolitan areas where these job contractions were concentrated, however, these losses were offset by employment growth in middle-skill clerical jobs and lower-skill service jobs, including new categories of work—jobs that employed workers of similar demographic characteristics to those who worked as switchboard operators in the prior generation.

These examples may be familiar, but the point is general. The creation of demand for new expertise is a critical force that counterbalances the tendency of

___________________

23 J. Feigenbaum and D.P. Gross, 2024, “Answering the Call of Automation: How the Labor Market Adjusted to Mechanizing Telephone Operation,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 139(3):1879–1939.

automation to erode the value of old expertise.24 Figure 4-2 documents that more than half (60 percent) of the job activities that U.S. workers performed in 2018 were not present—had not yet been invented—as of 1940. What makes work “new” is that it requires expertise that was not previously in demand or perhaps did not exist (e.g., pediatric oncology, AI prompt engineering, or pneumatic hammering). Human expertise has remained valuable not because it is timeless but because it is continually changing. The force of innovation has been central to this replenishment. But this is not the only force: rising wealth, changing demographics, and changing tastes also play central roles.25

Both automation of traditional work and new task creation occur simultaneously, but there is no reason to assume that these forces exactly offset one another. For much of the 20th century, these forces were in rough balance—new technologies not only displaced existing tasks but also complemented humans, generating new tasks and enabling humans to perform higher-quality work. This balance underpinned the period’s wage and employment growth and shared prosperity.

Sometime after approximately 1970, for reasons that are not well understood, this balance was lost. Automation maintained its pace or even accelerated over the following decades, but new task creation slowed, especially for those workers without 4-year degrees.26 Computerization displaced noncollege workers from factories and offices, and blue-collar workers were displaced by import competition.27 Although employment is rising in health and skilled personal service occupations that may ultimately constitute a “new middle,” this growth has not yet fully offset the loss of equivalently well-paid traditional middle-skill jobs, particularly among noncollege males.28 Non-college-educated workers increasingly have taken shelter in low-paid service sector jobs such as food service, security, cleaning, and entertainment. Their work is socially valuable, as above,

___________________

24 D. Acemoglu and P. Restrepo, 2018, “The Race Between Man and Machine: Implications of Technology for Growth, Factor Shares, and Employment,” American Economic Review 108(6):1488–1542; and D. Autor, C. Chin, A.M. Salomons, and B. Seegmiller, 2022, “New Frontiers: The Origins and Content of New Work, 1940–2018,” NBER Working Paper No. 30389, August.

25 D. Autor, C. Chin, A.M. Salomons, and B. Seegmiller, 2022, “New Frontiers: The Origins and Content of New Work, 1940–2018,” NBER Working Paper No. 30389, August.

26 D. Acemoglu and P. Restrepo, 2019, “Automation and New Tasks: How Technology Displaces and Reinstates Labor,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 33(2):3–30; D. Autor, C.M. Chin, A. Salomons, and B. Seegmiller, 2022, “New Frontiers: The Origins and Content of New Work, 1940–2018,” NBER Working Paper No. w30389, August; and D. Acemoglu and S. Johnson, 2023, Power and Progress: Our 1000-Year Struggle Over Technology and Prosperity, PublicAffairs.

27 D.H. Autor, D. Dorn, and G.H. Hanson, 2013, “The China Syndrome: Local Labor Market Effects of Import Competition in the United States,” American Economic Review 103(6):2121–2168.

28 Examples of this new middle include “sales representatives, truck drivers, managers of personal service workers, heating and air conditioning mechanics and installers, computer support specialists, self-enrichment education teachers, event planners, health technologists and technicians, massage therapists, social workers, marriage and family counselors, audiovisual technicians, paralegals, healthcare social workers, chefs and head cooks, and food service managers.” See M.R. Strain, 2020, “The Middle Class Is Changing, Not Dying.” Discourse, April 20, https://www.discoursemagazine.com/p/the-middle-class-is-changing-not-dying.

SOURCE: D. Autor, C.M. Chin, A. Salomons, and B. Seegmiller, 2024, “New Frontiers: The Origins and Content of New Work, 1940–2018,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 139(3):1399–1465, https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjae008.

but because the positions require little in the way of specialized education, training, or expertise, they pay poorly.29

This expertise framework helps shed light on the following key questions:

- Is AI likely to raise wages or lower them, and for whom?

- Will AI further expand wage inequality or potentially reduce it?

- Will AI make worker expertise more valuable, or will it make it less necessary?

- What types of expertise are likely to be displaced by AI automation, and what types of expertise are likely to be made more valuable?

Before turning to AI, it is instructive to consider two prior technological revolutions: the Industrial Revolution and the computer revolution.

Table 4-1 provides an overview of the impact of each of these eras on the demand for expertise, and Table 4-2 provides a rubric for different types of expertise.

___________________

29 D. Acemoglu, D. Autor, and S Johnson, 2023, “Can We Have Pro-Worker AI? Choosing a Path of Machines in Service of Minds,” MIT Shaping the Future of Work Initiative Policy Memo, September 19, https://shapingwork.mit.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Pro-Worker-AI-Policy-Memo.pdf.

TABLE 4-1 Impacts of Three Technological Eras on the Demand for Expertise

| Expertise Substituted/Made Obsolete | Expertise Augmented/Newly Demanded | Ease of Acquiring Needed Expertise | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Industrial era | Artisanal expertise (e.g., weaving, shoemaking, clock-making). | Mass expertise. Learning rules and mastering tools for manufacturing/production and office/information tasks (“accomplishing routine tasks”). |

Literacy and numeracy needed. Owing to high school movement, workers well prepared to acquire industrial era mass expertise. |

| Information era | Mass expertise. Expertise in learning rules and mastering tools (i.e., carrying out routine tasks). | Elite expertise. Combining expert knowledge with acquired judgment to make high-stakes decisions in nonstandard cases. Needed for abstract decision making, communications, and management. Elite expertise becomes the bottleneck when routine tasks are automated. |

Often requires a college degree or significant post-secondary education plus years of hands-on supervised practice or apprenticeship (e.g., medical doctor, pilot). Less than one-third of workers qualified. |

| Artificial intelligence era | May substitute for some “elite expertise”—making it less scarce. | Translational expertise. Combining expert judgment with inputs and guidance from artificial intelligence to carry out “elite expert” tasks. |

May require foundational training in subject expertise (e.g., law, medicine) plus acquired judgment without necessarily requiring professional levels of post-secondary education. |

TABLE 4-2 Types of Expertise: A Rubric

| Definition | Educational Requirements | Representative Occupations | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Artisanal expertise | Mastery of full sequence of steps for producing a product. | Apprenticeship | Blacksmith, wheelwright, clockmaker |

| Mass expertise | Executing precise rules-based tasks (routine tasks) in production or office environments. Learning rules, mastering tools. | Typically, high school education and on-the-job training/experience | Production worker, machinist, typist, bookkeeper |

| Elite expertise | Combining formal training with acquired judgment to make high-stakes decisions (nonroutine cognitive tasks). | Often 4-year college degree plus graduate or professional degree | Medical doctor, lawyer, scientist, engineer, nurse, architect |

| Translational expertise | Combining foundational technical knowledge with supporting tools to accomplish high-stakes tasks. | Likely post-secondary vocational training that may not require a 4-year degree | Nurse practitioner, tradesperson, construction contractor |

DEMAND FOR EXPERTISE IN THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION

Although the Industrial Revolution is a monumentally broad topic, the discussion here will summarize its implications for work in the simplest possible terms. Prior to the Industrial Revolution, there was no concept of mass production. Most goods were handmade one at a time by skilled craftspeople (artisans). No two instances of the same item—be it a horseshoe, a wagon wheel, or a work boot—were identical. Artisanal work was generally expertise-intensive. The artisan was responsible for producing the complete product, not simply for accomplishing a few steps along the way.

This changed in the 18th and 19th centuries as industries mastered a new form of work organization that became known as mass production.30 Mass production involved breaking the complex work of artisans into discreet, self-contained, and often quite simple steps that could be carried out mechanistically by a team of production workers, often abetted by machinery and overseen by managers.31 As a case in point, the Ford Motor Company’s River Rouge production plant, an archetype of mass production, employed more than 100,000 workers at its peak.32

The transition from artisanal to mass production profoundly changed the demand for worker expertise—what expertise was needed, who supplied it, and what wages it commanded. Most directly, mass production reduced demand for artisanal labor by providing a faster, cheaper production system that combined high-tech machinery, managerial expertise, and vast numbers of comparatively unskilled workers.33 Although the skilled British weavers and textile workers who rose up in protest against mechanization in the 19th century—the eponymous Luddites—are frequently derided for their naive fear of technology, these fears were not misplaced. As the economic historian Joel Mokyr and colleagues wrote in 2015, “The handloom weavers and frame knitters with their little workshops were quite rapidly wiped out by factories after 1815.”34

But mass production did not merely displace existing expertise. It created enormous demand for new forms of expertise. Initially, this demand was most concentrated on uneducated, untrained workers who could perform repetitive production steps. Whereas skilled artisans were almost necessarily adults—reflecting the years of

___________________

30 D. Hounshell, 1984, From the American System to Mass Production, 1800–1932: The Development of Manufacturing Technology in the United States, No. 4, Johns Hopkins University Press.

31 For detailed examples, see J. Atack, R.A. Margo, and P.W. Rhode, 2019, “Automation of Manufacturing in the Late Nineteenth Century: The Hand and Machine Labor Study,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 33(2):51–70.

32 Ford Motor Company, n.d., “Company Timeline: 1917,” https://corporate.ford.com/about/history/company-timeline.html.

33 C. Goldin and L.F. Katz, 1998, “The Origins of Technology-Skill Complementarity,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 113(3):693–732.

34 J. Mokyr, C. Vickers, and N.L. Ziebarth, 2015, “The History of Technological Anxiety and the Future of Economic Growth: Is This Time Different?” Journal of Economic Perspectives 29(3):31–50. Mokyr and colleagues were in turn drawing on D. Bythell, 1969, The Handloom Weavers: A Study in the English Cotton Industry During the Industrial Revolution, Cambridge University Press.

apprenticeship required to master their trades—early factories made abundant use of children and unmarried women. Conditions in early factories were often grueling, dangerous, and exhausting. And the only essential capacities needed were physical dexterity and willingness to work (or inability to not work) under punishing conditions, often for extremely low pay.35

But these initial abysmal conditions improved in the early 20th century as a consequence of three powerful undercurrents. First, the enormous productivity gains stemming from the Industrial Revolution generated vast wealth while reducing the cost of everyday products, leading to a surge in demand. Households could for the first time afford luxuries such as full wardrobes, factory-made household goods, and new industrial products, including electric toasters and irons. The rapid expansion of industrial activity created new demand for labor and bid up wages. Rising incomes in turn enabled a change of norms, spurring laws restricting child labor and mitigating dangerous working conditions. This further promoted rising living standards.

Second, and as important, while early factory work required little skill or training, as new products and new production techniques emerged, workers operating and maintaining complex equipment needed expertise and training to carry out their work, such as skills in machining, fitting, welding, chemical processes, textiles, dyeing, calibrating precision instruments, and so on.36 The growing need for expertise was not limited to production workers. The demand for educated and highly trained workers rose across the board in maintenance, engineering, production infrastructure, product design, logistics, accounting, communications, sales, and management to coordinate these many sophisticated parts. Whereas mass production was initially expertise-displacing, relying primarily on cadres of untrained workers accomplishing rote tasks under brutal conditions, it ultimately generated demand for mass expertise. Workers increasingly required experience, training, and formal knowledge to master and manage sophisticated tools and valuable materials in a complex environment.37 In a phrase, workers needed to master tools and follow rules. (In contemporary economic parlance, many of these rule- and-tool activities would be classified as “routine tasks.” Similarly, mass expertise could be defined as the skill to carry out routine tasks in production and office environments.)

Ultimately, although the rise of mass production eclipsed a substantial stock of artisanal expertise, the demand for new expertise that it generated proved vastly larger than these displacement effects. Much of the expertise required was novel. There had

___________________

35 In Britain, textile workers were often orphans who were placed in indentured servitude to the mill, which provided food and boarding and, perhaps, education until the children were released at age 18.

36 Of course, the design and integration of early industrial era tools and factories required mechanical expertise that was exceedingly rare in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. See M. Kelly, J. Mokyr, and C.Ó. Gráda, 2023, “The Mechanics of the Industrial Revolution,” Journal of Political Economy 131(1):59–94.

37 C. Goldin and L.F. Katz, 1998, “The Origins of Technology-Skill Complementarity,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 113(3):693–732.

been no demand for electricians until electricity found industrial and consumer uses. There were no skilled machinists prior to the invention of the machines that they operated. And there were no production engineers prior to the rise of mass production. In short, much of the expertise made valuable by the era of mass production was not required and did not exist before changes in technology and work organization made that expertise essential for delivering goods and services. The new ideas, institutions, and technologies of the Industrial Revolution thus spurred a vast expansion of the breadth and depth of expertise required of workers.

Third, the Industrial Revolution did not simply change industry. It fundamentally reshaped the basket of goods and services produced and consumed by citizens of industrializing countries. Even at the height of U.S. industrial activity in the early 1950s, less than 40 percent of employment was in industry (i.e., manufacturing, mining, and utilities) and only about 10 percent was in agriculture.38 The remainder was in services, a residual sector that encompasses everything from education to finance, insurance, real estate, business services, health care, food and hospitality, transportation, power generation, and travel (among other examples). Services comprised only one-third of employment in 1900 but encompassed more than half by 1950 and nearly four-fifths by 2020. The growth of services also generated vast new demands for labor and accompanying demands for new expertise. Many of these services were not themselves a direct product of the Industrial Revolution. But the transformative economic growth stemming from the Industrial Revolution allowed countries to focus their resources on these service activities, many of which would be considered nonessential in a poorer society. For example, while it would be a stretch to claim that the advent of mass production created the movie industry, neither the technology for producing and projecting movies nor the mass market consumer audience that was willing and able to pay for them would have been conceivable absent the rise in living standards that mass production afforded.39

This section thus far has addressed two of the three questions posed at the beginning of this chapter: What expertise was replaced (artisanal expertise), and what expertise was newly demanded by the Industrial Revolution (mass expertise)? The answer to the third question—relating to the feasibility of acquiring newly required expertise—is crucial to understanding why the Industrial Revolution created so much mass prosperity. Much of the expert work created in the industrial era demanded specific training and experience. Yet, workers typically needed no more than a high school education to enter these specialties. This fact was critically important because during the early 20th century,

___________________

38 L. Johnston, 2012, “The Growth of the Service Sector in Historical Perspective: Explaining Trends in US Sectoral Output and Employment, 1840–1990,” unpublished manuscript, College of Saint Benedict, Saint John’s University.

39 Clark makes the case that demand for services rises relative to demand for goods as societies get wealthier. See C. Clark, 1957, The Conditions of Economic Progress, London, Macmillan.

most of the United States moved to institute universal, publicly funded secondary school education.40 A large and growing fraction of U.S. adults was therefore equipped with the foundational formal skills needed to enter the expert occupations that were on the rise. To be clear, a high school education did not guarantee entry into the middle class, nor did high school–educated workers earn as much as those with college or post-college degrees. Moreover, discrimination against minorities and women denied a large fraction of the population access to these opportunities.41 But the excellence of U.S. public education in this era enabled a significant portion of the U.S. workforce—those who were not the targets of systemic discrimination—to make a successful transition into 20th century industry and services. Absent that educational foundation, it is unlikely that the United States would have reaped the same rapid, broadly shared income growth in the ensuing decades.42

DEMAND FOR EXPERTISE IN THE COMPUTER ERA BEFORE ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

Stemming from the innovations pioneered during World War II, the computer era reshaped this mass expertise trajectory. Like other general-purpose technologies that preceded it (e.g., electricity, the steam engine), the digital computer was highly applicable to a vast number of products, processes, and workplace settings. Relative to all technologies that had preceded it, however, the computer’s unique power was its ability to execute cognitive and manual tasks cheaply, reliably, and rapidly that were encoded in explicit, deterministic rules—that is, programs. This might seem prosaic: Do all machines not simply follow deterministic rules? At one level, yes. Machines do what they are built to do unless they are malfunctioning. But at another level, no. Distinct from prior machines, computers are symbolic processors that access, analyze, and act upon abstract information.43 Prior to the computer era, there was essentially only one tool for processing abstract information: the human mind. And not just any mind would do. Often, literacy and numeracy were required.

___________________

40 C. Goldin and L.F. Katz, 2009, The Race Between Education and Technology, Harvard University Press.

41 D. Autor, C. Goldin, and L.F. Katz, 2020, “Extending the Race Between Education and Technology,” AEA Papers and Proceedings 110:347–351.

42 Between 1947 and 1973, the rate of real mean family income growth was roughly identical across all five quintiles of the U.S. household income distribution, as well as among the top 5 percent of households. After 1973, this pattern skewed radically, with almost all income growth occurring among the top 40 percent, and especially the top 20 percent and 10 percent, of the income distribution. See C. Goldin and L.F. Katz, 2007, “Long-Run Changes in the Wage Structure: Narrowing, Widening, Polarizing,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 38:135–168. However, income levels, wealth, and access to opportunity differed radically between Black and White Americans owing to both historical and contemporary discrimination.

43 E. Brynjolfsson and L.M. Hitt, 2000, “Beyond Computation: Information Technology, Organizational Transformation and Business Performance,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 14(4):23–48.

The widespread adoption of powerful, inexpensive machines that could perform symbolic processing led to a seismic shift in the expertise demanded of workers. To understand how this worked, it is useful to conceptualize a job as performing a series of tasks required to accomplish a specific goal. Consider the tasks involved in writing a research report—such as assembling and managing a research team; collecting data; developing and testing hypotheses; performing calculations; drafting, editing, and proofreading; and distributing the report to readers. Before computers, most research and writing tasks would have been accomplished manually, aided by books, adding machines, typewriters, and postal mail. Human expertise would have been critical in such tasks as leading research teams, interpreting data, developing and testing hypotheses, calculating quantitative implications, and report writing.44

Computerization enabled the reassignment of a crucial set of tasks from humans to machines—in the above example, organizing data, performing calculations, proofreading text for misspellings, and distributing results. Now computers accomplish a well-delineated subset of tasks—that is, precise replicable steps that can be specified fully in advance. These are what economists typically refer to as “routine tasks” and what coders refer to as “programs.”45 Because a computer programmer must specify the sequence of steps required to accomplish a task before a computer can execute it, routine tasks are well suited to computerization. The cost of executing these programmed instructions has fallen dramatically. A 2007 paper by William Nordhaus estimated that the cost of performing a given computational task has fallen at least 1.7 trillion-fold since the predawn of the computer age, with most of that decline occurring since 1980.46

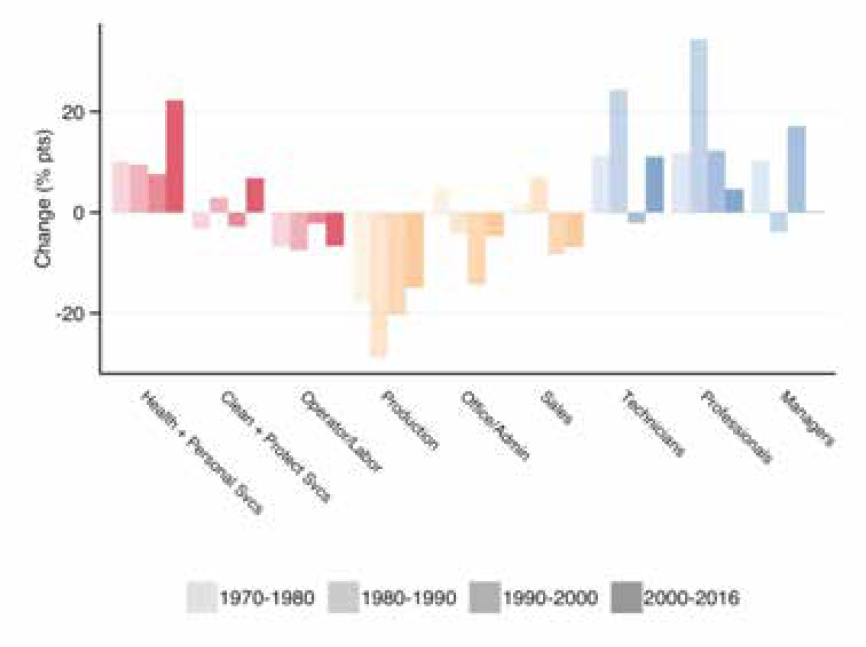

The spectacular fall in the cost of computing—accompanied by stunning improvements in speed and miniaturization—created powerful economic incentives for firms to use machines rather than workers to perform routine job tasks. This was a major step forward for productivity. But it was a mixed blessing for many workers because, in many instances, computers proved more proficient and far less expensive than workers in mastering tools and following rules. In the precomputer era, workers who specialized in skilled office and production tasks were the embodiment of the “mass expertise” of the industrial era. As computing advanced, it eroded the value of that mass expertise by displacing some of the core routine tasks that these workers performed. This catalyzed a contraction in the share of employment found in middle-skill production, office,

___________________

44 D. Autor, K. Basu, Z. Qureshi, and D. Rodrik, 2022, “An Inclusive Future? Technology, New Dynamics, and Policy Challenges,” Brookings Institution’s Global Forum on Democracy and Technology, May 31, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/an-inclusive-future-technology-new-dynamics-and-policy-challenges.

45 D.H. Autor, F. Levy, and R.J. Murnane, 2003, “The Skill Content of Recent Technological Change: An Empirical Exploration,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 118(4):1279–1333; F. Levy and R.J. Murnane, 2005, The New Division of Labor, Princeton University Press.

46 W.D. Nordhaus, 2007, “Two Centuries of Productivity Growth in Computing,” The Journal of Economic History 67(1):128–159.

administrative, and sales occupations (Figure 4-3).47 The routine tasks once supplied by these workers were still needed—in fact, such tasks were used ever more intensively as their cost fell—but they were now performed by machines.

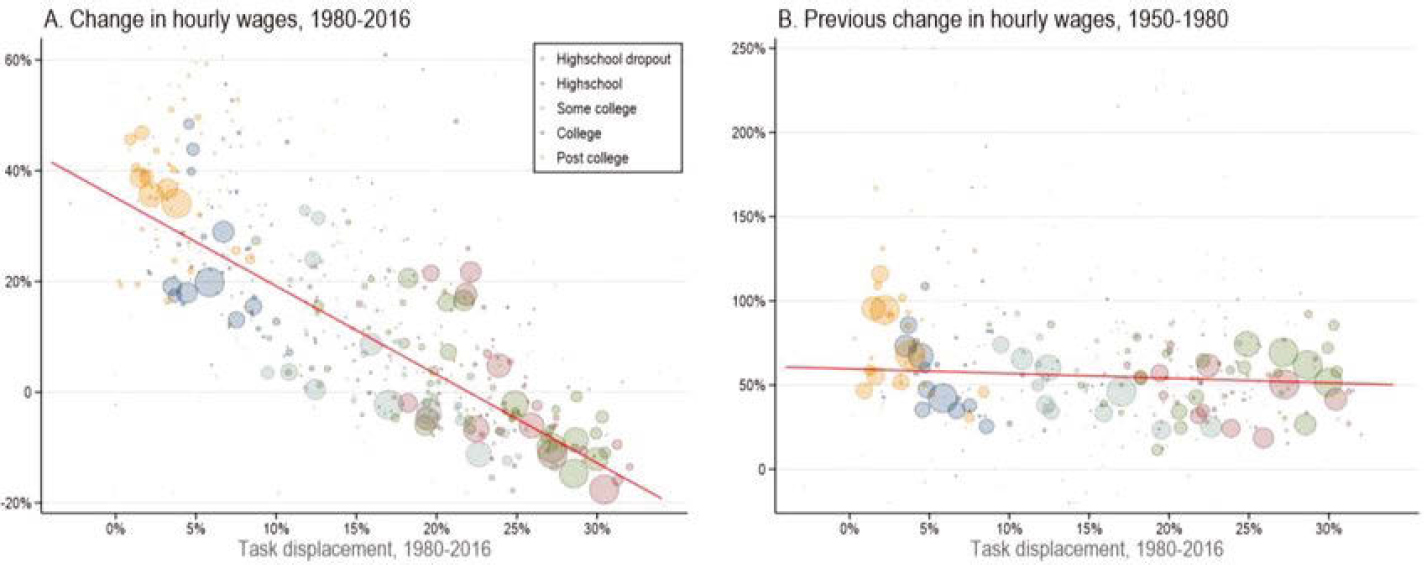

The wage consequences of routine task displacement were stark. Workers whose industries and occupations were most exposed to the automation of routine tasks saw sharp falls in their real earnings from 1980 forward, as shown in Panel A of Figure 4-4. Those most affected were disproportionately workers with a high school education but no post-secondary schooling, a group that—not by coincidence—fared extremely poorly overall during the past four decades (see Figure 4-1). Notably, this downward-sloping relationship between routine task–exposure and wage declines was absent before 1980, prior to the advent of large-scale commercial computerization (Figure 4-4, Panel B). This adds to the case that it was computerization specifically—not some other force—that depressed the earnings of workers who were specialized in routine task–intensive jobs. Computerization was therefore a critical force (though not the only factor) in the displacement and devaluation of the “mass expertise” that the industrial era had robustly demanded.

Not all tasks are, however, suited to computer execution. Many critical tasks follow rules and procedures that are known neither to computer programmers nor to the people who regularly perform them. The scientist and philosopher Michael Polanyi observed in 1966 that “we know more than we can tell,” meaning that people’s tacit knowledge often exceeds their explicit formal understanding.48 Making a persuasive argument, telling a joke, riding a bicycle, or recognizing an adult’s face in a baby photograph are subtle and complex undertakings that people seemingly accomplish with little effort without ever understanding precisely how. Mastery of these so-called “nonroutine” tasks is attained not through formal education (i.e., by learning the rules) but instead by learning-by-doing. A child learning to ride a bicycle does not need to study the physics of gyroscopes. But for a computer to control a motorized bicycle, a programmer would (in the pre-AI era) need to specify all the relevant instructions in advance. This observation—that human beings instinctively understand and perform many tasks, yet they cannot articulate the specific rules or procedures involved—is often referred to as Polanyi’s paradox.49

The capacity of computers to execute routine tasks with unprecedented speed at minimal cost proved highly complementary to managerial, professional, and technical

___________________

47 Similar evidence for European Union countries is found in M. Goos, A. Manning, and A. Salomons, 2014, “Explaining Job Polarization: Routine-Biased Technological Change and Offshoring,” American Economic Review 104(8):2509–2526.

48 M. Polanyi, 1966, The Tacit Dimension, University of Chicago Press.

49 D. Autor, 2014, “Polanyi’s Paradox and the Shape of Employment Growth,” Proceedings of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Jackson Hole Economic Policy Symposium, August.

SOURCE: D. Autor, 2019, “Work of the Past, Work of the Future,” AEA Papers and Proceedings 109:1–32, https://doi.org/10.1257/pandp.20191110. Copyright American Economic Association; reproduced with permission of the AEA Papers and Proceedings.

SOURCE: D. Acemoglu and P. Restrepo, 2022, “Tasks, Automation, and the Rise in U.S. Wage Inequality,” Econometrica 90(5):1973–2016, https://doi.org/10.3982/ECTA19815. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 DEED.

workers—whose work is concentrated in nonroutine abstract and interpersonal tasks.50 This complementarity arises because professional workers regularly make high-stakes decisions that are tailored to specific circumstances—for example, diagnosing a patient, crafting a legal brief, leading a team or organization, designing a building, or engineering a software product. For such tasks, knowing the rules is necessary but not sufficient; professionals must combine domain-specific knowledge with judgment and creativity to devise appropriate responses to novel problems. The discussion here refers to this as “elite expertise”: the technical knowledge and acquired judgment needed to make high-stakes, one-off decisions. Computerization complements elite expertise by enabling professionals to spend less of their time acquiring information and conducting routine analysis and more of their time interpreting and applying that information. It thus augments the accuracy, productivity, and thoroughness of professional decision making, rendering professional expertise more valuable. It is therefore no coincidence that the earnings of workers with 4-year and especially graduate degrees (in law, medicine, science, engineering, design, and management) rose steeply as computerization advanced.

These advances in routine task execution came at a cost to others. Computerization augmented the value of elite expertise in part by automating away the mass expertise of the workers on whom professionals used to rely. This created inequality in opportunity because entry into the professions is expensive, requiring both high levels of formal education—often in the form of graduate degrees and professional credentials—and significant time spent in training—for example, medical residencies, postdoctoral fellowships, junior status in law or academia, management of small organizations, and so on. In the era of mass production, the advancing high school movement dovetailed with the skill demands of the industrializing economy, so the supply of high school–educated workers kept pace with the rapidly rising demand. To use the terminology of Goldin and Katz, in the “race between education and technology” in the early decades of the 20th century, education decidedly won that heat.51 But there was no corresponding college movement on the scale of the high school movement to meet the rising demands for elite expertise in the computer era. Instead, the rising demand for elite expertise in this period contributed to rising inequality, with earnings growth concentrated among the educated elite.

Not all nonroutine tasks require elite expertise, however. Some tasks—such as cleaning rooms, waiting tables, picking items in a warehouse, driving a vehicle in city traffic, or assisting elderly people with daily living—rely on dexterity, simple

___________________

50 On the value of social skills, see D.J. Deming, 2017, “The Growing Importance of Social Skills in the Labor Market,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 132(4):1593–1640.

51 For a deep historical account, see C. Goldin and L.F. Katz, 2009, The Race Between Education and Technology, Harvard University Press.

communication, and common sense.52 Because these nonroutine manual (or “service”) tasks draw on substantial reservoirs of tacit knowledge, they have proved stubbornly difficult to automate. Yet, because the vast majority of workers can master these tasks with modest training, the workers performing service tasks typically earn low wages.

Computerization did not improve this situation. Although computerization neither automates the central tasks of nonroutine manual work nor strongly augments the workers doing these tasks, it substantially affected this work indirectly—in many cases not positively. As the automation of routine tasks eroded employment in clerical, administrative, and production occupations, many of the noncollege workers who would have performed this work were increasingly shunted into hands-on service occupations such as food service, cleaning and janitorial services, security, and personal care. This placed downward pressure on wages in this (already) low-wage work, providing an additional force for rising inequality.53

Applying the three questions posed at the beginning of this chapter to the computer era helps to weave together these threads:

- What expertise was substituted or made obsolete in the computer era? Mass expertise. Expertise in carrying out middle-skilled, routine-intensive tasks in offices and factories was devalued as computers could carry out this work faster, cheaper, and more accurately than the workers they replaced.54

- What expertise was augmented or newly demanded? Elite expertise. Abstract reasoning, strong interpersonal and leadership skills, and expertise in high-stakes, situation-specific decision making were more valuable as computers automated the routine components of these tasks. As the value of expert nonroutine tasks rose, workers with graduate degrees (“elite expertise”) were the biggest beneficiaries.

- How feasible was it for workers to acquire newly valuable expertise? Acquiring elite expertise is costly in time and money. If workers could have entered growing, highly educated professions rapidly, many would have benefited from the

___________________

52 Although half-a-dozen years ago, autonomous vehicles were predicted to overtake and replace human drivers rapidly, the problem has proved much harder than anticipated because the complexity of high-stakes nonroutine decision making required is immense; even experienced drivers find the process almost effortless. See S.E. Shladover, 2021, “‘Self-Driving’ Cars Begin to Emerge from a Cloud of Hype,” Scientific American, September 21, https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/self-driving-cars-begin-to-emerge-from-a-cloud-of-hype.

53 D. Acemoglu and P. Restrepo, 2022, “Tasks, Automation, and the Rise in US Wage Inequality,” Econometrica 90(5):1973–2016.

54 By contrast, dexterous physical tasks that are performed in relatively fluid, nonstandardized environments, such as construction sites, homes, or restaurants, have not been subject to automation because the lack of environmental control makes these tasks nonroutine. As Herbert Simon wrote in 1960, “Environmental control is a substitute for flexibility.” Factories enable automation by reducing the need for flexibility. This is far harder to accomplish on construction sites. See H.A. Simon, 1960, “The Corporation: Will It Be Managed by Machines?” pp. 17–55 in Management and the Corporations, M.L. Anshen and G.L. Bach, eds., McGraw-Hill.

- labor market changes wrought by computerization. But the virtuous synergy between public education and new demands for expertise seen in the early 20th century was absent during the computer revolution. Mass education did not provide the needed number of 4-year degrees that would have allowed workers to enter expanding professions, often through graduate training, and that would have been required to maintain the shape of the earnings distribution. Moreover, college enrollment among U.S. adults, especially U.S. males, responded with remarkable sluggishness to the rising demand for educated workers after 1980.55 Rather than catalyzing a new era of “mass expertise,” computerization instead bolstered a decades-long trend of rising inequality. Workers with expertise in professional, technical, and managerial tasks saw their skills become even more valuable. Workers lacking elite expertise were increasingly relegated to nonexpert service work as the broad middle set of occupations was eroded by automation. Thus, in the long-running race between education and technology, education lost decisively in these decades.

DEMAND FOR EXPERTISE IN THE ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE ERA

Earlier chapters discussed the technical attributes of AI. This chapter discusses its implications for the operation of the labor markets—specifically, its potential impact on the demand for expertise. These potential impacts stem from one attribute that AI possesses and previous technologies lacked: the capacity to master and execute nonroutine tasks. While in the pre-AI era engineers struggled to program computers to accomplish tasks that humans understand only tacitly, this is no longer an intrinsic obstacle for AI. AI learns by example, mastering tasks without explicit instruction and acquiring capabilities that it was not designed to perform. In short, AI can infer tacit relationships, meaning that it has made substantial progress toward overcoming Polanyi’s paradox.

To understand the power of this tacit learning capability, consider one simple application: identifying pictures of chairs. Although it seems trivial, explicitly defining what makes a chair a chair is extraordinarily challenging: Must it have legs and, if so, how many? Must it have a back? What range of heights is acceptable? Must it be comfortable, and what makes a chair comfortable? Writing the rules for this problem is maddening.56

___________________

55 D. Autor, 2014, “Skills, Education, and the Rise of Earnings Inequality Among the ‘Other 99 Percent,’” Science 344(6186):843–851.

56 See D. Autor, 2022, “The Labor Market Impacts of Technological Change: From Unbridled Enthusiasm to Qualified Optimism to Vast Uncertainty,” NBER Working Paper No. 30074, May.

If written too narrowly, they will exclude stools and rocking chairs. If written too broadly, they will include tables and countertops. In a well-known paper, Grabner and colleagues argue that the fundamental problem is that what makes a chair a chair is its suitability for sitting upon.57 What makes something “suitable” for sitting upon is as elusive as the original problem. Given this morass, this chair classification task would be categorized as “nonroutine” for purposes of conventional computing—a human task rather than a machine task.

Fast forward to the present, and AI can “solve” this classification problem but not by following explicitly programmed rules. Rather, AI infers the solution inductively by training on examples. Given a suitable database of tagged images and sufficient computing power, AI can infer what image attributes are statistically associated with the label “chair” and can then use that information to classify untagged images of chairs with a high degree of accuracy.58 It can then refine this typology as its outputs are affirmed or corrected by human users. In general, the rules that AI uses for this classification remain tacit. Nowhere in the learning process does AI formally codify or reveal the underlying features (i.e., rules) that constitute “chair-ness.” The classification instead emerges from layers of learned statistical associations with no human-interpretable window into that decision-making process. This absence of transparency, which David Autor refers to as “Polanyi’s revenge”—“computers now know more than they can tell us”—creates a new set of challenges touched upon briefly below.59

Three key properties emerge from AI’s capacity to infer tacit relationships:

- AI tools can learn and adapt. AI, when based on machine learning, acquires capabilities from examples, draws inferences from unstructured information, and generalizes acquired capacities across domains—for example, large language models (LLMs) can craft prose, explain jokes, and write computer code. This capacity is distinct from prior technologies that were, in a fundamental sense, scripted to execute prespecified actions that were encoded mechanically or symbolically.

- AI tools are generative. AI can produce novel output that would be judged by many casual observers and professional experts to be competent; useful; and in some cases, creative. While some earlier pre-AI software packages

___________________

57 H. Grabner, J. Gall, and L. Van Gool, 2011, “What Makes a Chair a Chair?” pp. 1529–1536 in Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, IEEE Computer Society, https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2011.5995327.

58 E. Brynjolfsson and T. Mitchell, 2017, “What Can Machine Learning Do? Workforce Implications,” Science 358(6370):1530–1534; E. Brynjolfsson, T. Mitchell, and D. Rock, 2018, “What Can Machines Learn, and What Does It Mean for Occupations and the Economy?” AEA Papers and Proceedings 108:43–47.

59 D. Autor, 2022, “The Labor Market Impacts of Technological Change: From Unbridled Enthusiasm to Qualified Optimism to Vast Uncertainty,” NBER Working Paper No. 30074, May.

- generated music, prose, and original graphical art, the results were highly programmatic. Works created by contemporary AI tools are in many cases on par with human creations.

- AI tools may alter the order of operations between human ideation, expertise creation, and subsequent expertise erosion (i.e., automation). Historically, human expertise has preceded and was necessary for subsequent automation. New technologies were conceived by inventors, engineers, and designers; deployed using novel tools and expertise; and (if successful) broadly adopted, along with supporting expertise. Over the longer run, these technological innovations might be automated as the relevant processes and knowledge are codified and routinized.

A corollary to the third property is that AI will likely reverse this flow of innovation. In numerous conceivable cases, AI will solve problems that presently confound current understanding. Humans will then be left to decipher how AI solved the problem and how this solution actually works.60 The same logic applies to other well-known examples, such as AI’s progress on the epochal problem of protein folding61 or its mastery of open-ended games like Go. It is highly plausible that frontier innovations will increasingly precede, and perhaps defy, human understanding. Humans will then face a substantial challenge both in understanding how AI systems accomplish tasks and in supervising AI systems to thwart erroneous or dangerous decisions.

These challenges are already visible in the complex interaction between partially autonomous vehicles and their human drivers. In the vast majority of typical driving settings, partially autonomous vehicles are arguably more attentive and less error-prone than human drivers. But they are susceptible to making catastrophic errors that an attentive driver would not make—for example, driving at highway speed into a roadside safety vehicle, as some Tesla vehicles have done.62 In theory, the combination of human drivers and partially autonomous vehicles should be safer than either operating alone. In reality, because drivers have difficulty sustaining passive attention, they are often ill-prepared to accept an emergency “handoff” when required. This problem will likely become more acute as the proficiency of autonomous vehicles improves and the attentiveness and even the underlying driving expertise of human drivers atrophy.

___________________

60 For a vivid example of this process in the case of judicial bail decisions, see J. Ludwig and S. Mullainathan, 2023, “Machine Learning as a Tool for Hypothesis Generation,” NBER Working Paper No. w31017, March.

61 R.F. Service, 2020, “‘The Game Has Changed.’ AI Triumphs at Protein Folding,” Science 370(6521):1144–1145.

62 F. Siddiqui, R. Lerman, and J.B. Merrill, 2022, “Teslas Running Autopilot Involved in 273 Crashes Reported Since Last Year,” Washington Post, June 15.

Implications of Artificial Intelligence for the Demand for Expertise

Before applying the three-part rubric to consider how demand for human expertise may be reshaped in the AI era, two major caveats are needed. First, this report was written in the early years of what appears to be a revolution in machine capabilities. There is almost no representative or authoritative evidence so far to guide forecasts of how the widespread adoption and continued advancement of AI may affect work and workers. Second, commentators and experts of all stripes—social and natural scientists, historians, and journalists—have an almost unblemished record of incorrectly forecasting the long-run consequences of technological innovations. For example, Aristotle prophesied in the fourth century BC that if “the shuttle would weave and the plectrum touch the lyre without a hand to guide them, chief workmen would not want servants, nor masters slaves.”63 But slavery was not universally abolished for more than 150 years after the 1785 invention of the power loom,64 and in some places, it even persists today.65 The study committee does not claim greater foresight than Aristotle.

As important, in attempting to forecast the “consequences” of technological change, there is a risk of portraying the future as a fate to be divined rather than an expedition to be undertaken. This would be an error. Both the technologies developed and the manner in which they are used—for exploitation or emancipation, for broadening prosperity or concentrating wealth—are determined foremost not by the technologies themselves but by the incentives and institutions in which they are created and deployed.66 For example, scientific mastery of controlled nuclear fission in the 1940s enabled nations to produce both massively destructive weapons and carbon-neutral electricity generation plants. Eight decades on, countries have prioritized these technologies differently. North Korea possesses an arsenal of nuclear weapons but no civilian nuclear power plants. Japan, the only country against which an offensive nuclear weapon has been used, possesses no nuclear weapons and 12 civilian nuclear power plants in current operation.67

AI is far more malleable and broadly applicable than nuclear technology; hence, the range of both constructive and destructive uses is far wider. Some nations already use AI to surveil their populations heavily, squelch viewpoints that depart from official

___________________

63 Aristotle. Politics, Translated by H. Rackham, Harvard University Press, 1932, book 1, section 1253b.

64 M. Cartwright, 2023, “The Textile Industry in the British Industrial Revolution” in World History Encyclopedia, https://www.worldhistory.org/article/2183/the-textile-industry-in-the-british-industrial-rev and M.A. Klein, 2002, Historical Dictionary of Slavery and Abolition, Scarecrow Press, p. 22.

65 International Labour Organization, 2024, “Joining Forces to End Forced Labor,” September 9, https://www.ilo.org/publications/joining-forces-end-forced-labour.

66 For an in-depth treatment of this topic, see D. Acemoglu and S. Johnson, 2023, Power and Progress: Our 1000-Year Struggle Over Technology and Prosperity, PublicAffairs.

67 Arms Control Association, 2024, “Nuclear Weapons: Who Has What at a Glance,” July, https://www.armscontrol.org/factsheets/nuclear-weapons-who-has-what-glance and International Atomic Energy Agency, 2024, “Country Nuclear Power Profiles,” AIEA Non-serial Publications, https://cnpp.iaea.org/public.

narratives, and identify (and subsequently punish) dissidents—and they are exporting these capabilities rapidly to like-minded autocracies.68 In other settings, the same underlying AI technologies are used to advance medical drug discovery (including the development of COVID-19 vaccines), enable real-time translation of spoken languages, and provide free online tutoring in frontier educational subjects.

What these examples highlight is that the potential effects of AI on the work of the future depend critically on what objectives individuals, corporations, educational institutions, and governments pursue; what investments they make; and even what vision of the future guides these decisions. The discussion below considers possible paths for how labor markets may be shaped by the development and deployment of AI, recognizing that none of these paths are inevitable. The fact that some paths are more desirable than others provides a strong impetus for choosing policies carefully.

What Expertise Will Be Substituted or Made Obsolete?

It is reasonable to assume that AI tools will likely soon equal or exceed human capacities in numerous “elite expert” tasks (at substantially lower cost): writing business and legal documents; digesting, distilling, and synthesizing research; producing presentations, charts, illustrations, and animations; performing state-of-the-art medical diagnoses and providing treatment plans; solving engineering and design problems; managing complex systems such as power grids, server clusters, and air traffic control systems; and developing educational content.69

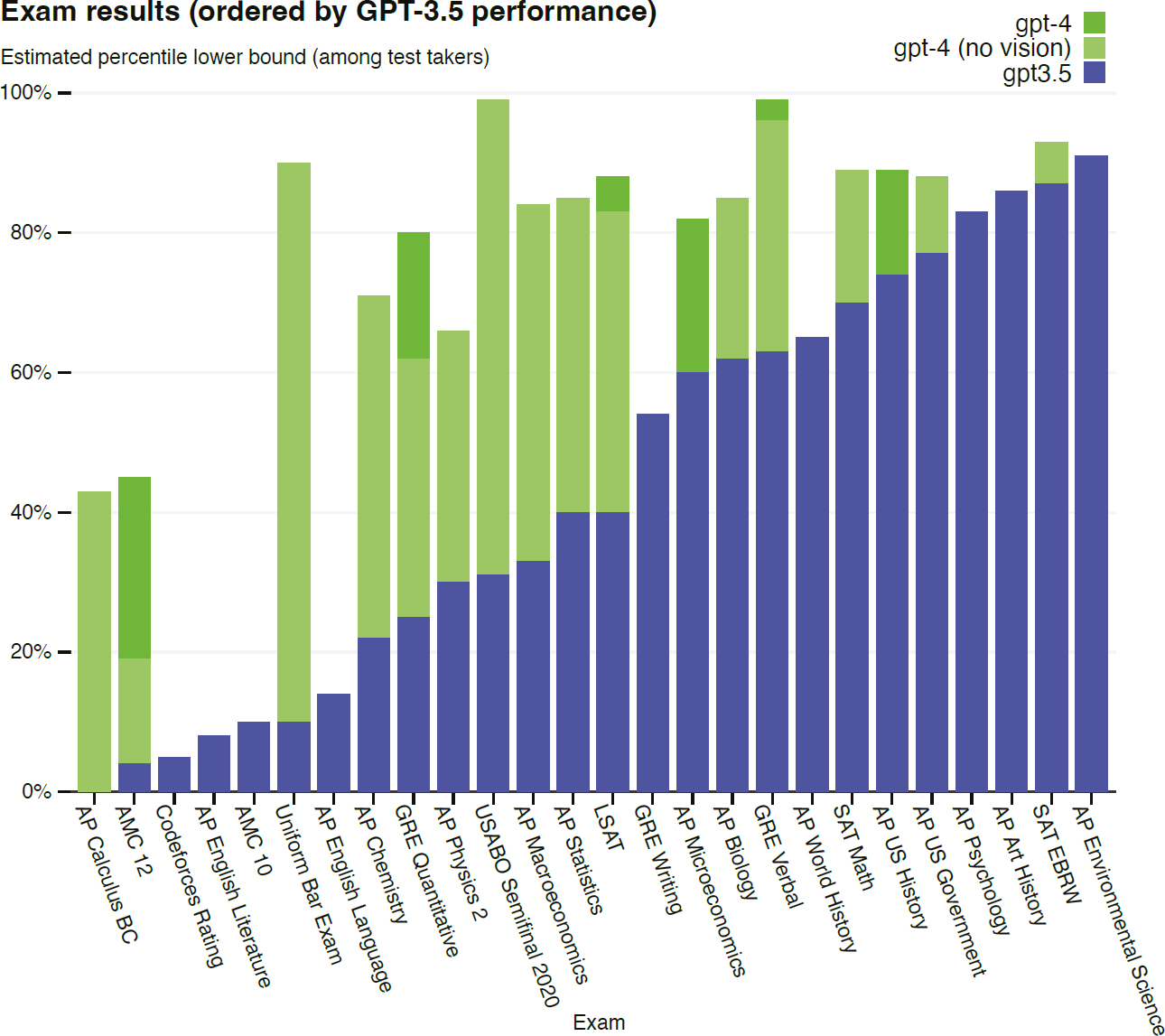

The rapid progress of AI in these domains is illustrated in Figure 4-5, which shows that OpenAI’s ChatGPT v4.0 LLM is currently able to score above the 80th percentile on numerous high school Advanced Placement exams (statistics, macroeconomics, microeconomics, and psychology) as well as on the Uniform Bar Examination, the quantitative reasoning section of the Graduate Record Examination, and the mathematics section of the SAT.70 While acing standardized tests is not equivalent to practicing successfully in a professional environment (i.e., lawyers do not take standardized tests for a living), these results strongly suggest that LLMs will be able to carry out some of the core nonroutine tasks of highly paid professionals in the years ahead.

___________________

68 M. Beraja, A. Kao, D.Y. Yang, and N. Yuchtman, 2021, “AI-tocracy,” NBER Working Paper No. 29466, November, National Bureau of Economic Research, http://www.nber.org/papers/w29466.

69 Relatedly, Daniel Rock and colleagues used a decade of data from private-sector posting sources to create a geometric analysis of change in occupations. They found that digital technologies are densifying the occupational landscape—increasing occupations by as much as 4 percent per year with less “distance” as defined by specific skill needs between occupations. If this were to hold during the introduction of generative AI, it would add emphasis to the potential value of expansive access to targeted training. See D. Rock, 2022, “Work2Vec: Measuring the Latent Structure of the Labor Market,” ESCoE Economic Measurement Webinars, https://escoe-website.s3.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/25103832/Daniel-Rock-Slides.pdf.

70 This model was state of the art as of March 2023. Readers of this report will surely encounter more powerful successors to this model.