Serious Illness Care Research: Exploring Current Knowledge, Emerging Evidence, and Future Directions: Proceedings of a Workshop (2024)

Chapter: Proceedings of a Workshop

Proceedings of a Workshop

WORKSHOP OVERVIEW1

Phillip E. Rodgers, The George A. Dean, M.D. Professor and Chair, Department of Family Medicine, University of Michigan Medical School, observed that “we are at a critical time in the field” of serious illness care, and “as we look to the future to meet the challenges of an aging society” with increasingly complex health care needs, a “high-quality evidence base for the work we do is essential to meet the moment.” Translating evolving research and evidence into improved care is critical, as Jean Kutner, distinguished professor of medicine and associate dean for clinical affairs at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, emphasized: “We have made tremendous advances in the field, and we owe it to those we care for with serious illness and their families to ensure we are providing the best evidence-based care.”

To examine the current and future state of serious illness care research, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s Roundtable

___________________

1 The planning committee’s role was limited to planning the workshop, and the Proceedings of a Workshop has been prepared by the workshop rapporteurs as a factual summary of what occurred at the workshop. Statements, recommendations, and opinions expressed are those of individual presenters and participants and are not necessarily endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, and they should not be construed as reflecting any group consensus.

on Quality Care for People with Serious Illness hosted a public workshop, Serious Illness Care Research: Exploring Current Knowledge, Emerging Evidence, and Future Directions, on November 2–3, 2023. Workshop speakers representing a diverse range of disciplines, including nursing, medicine, health economics, biostatistics, social work, and implementation science, explored gaps in serious illness care research, suggested best approaches for addressing those gaps, and identified high-priority areas for future research; the ultimate goal of such research is improving care for people of all ages and all stages of serious illness, their families, and care partners. The 1.5-day workshop had eight sessions. It opened with presentations that provided the critical perspective of individuals living with serious illness, their families, and caregivers. This discussion on lived experience was followed by an overview of the past, present, and future states of serious illness care research. The second and third sessions examined approaches for improving evidence generation to address gaps in the research in methodology and study design (Session 2) and outcome measures and data capture (Session 3). The fourth and final session of the first day featured presentations on barriers and facilitators to integrating health equity in serious illness care research.

The second day opened with a session on the role of implementation science in translating serious illness care research into practice. The final session wove together the key themes raised throughout the workshop and discussed the future of serious illness care research to guide the field.

The sessions included a mix of presentations, panel discussions, and Q&A periods with participants. This Proceedings of a Workshop summarizes the presentations and discussions. The speakers, panelists, and participants presented a broad range of views and ideas. Box 1 summarizes suggestions on ways to expand the evidence base for serious illness care research provided by individual workshop participants. Appendixes A and B contain the workshop Statement of Task and workshop agenda, respectively. The speakers’ presentations (as PDF and audio files) have been archived online.2

___________________

2 For additional information, see https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/40554_11-2023_serious-illness-care-research-exploring-current-knowledge-emerging-evidence-and-future-directions-a-workshop (accessed March 25, 2024).

BOX 1

Suggestions Made by Individual Workshop Participants for Ways to Expand the Evidence Base for Serious Illness Care Research

Integrating Lived Experience of Patients, Families, Care Partners, and Other Collaborators into Research

- Recognize that no one knows a serious illness and the urgency and importance of improving care better than the person living it and that patients improve research when treated as experts. (Hall, Kluger)

- Principles of parity and respect need to be part of all aspects of collaborative research with lived experience experts. (Kluger)

- Thoughtful collaboration with people with lived experience, including patients, care partners, and other key partners, is critical to developing research questions, priorities, and outcomes. (Hall, Kluger, Kutner, Meier, Morrison, Sumrall, Yarab)

- Training programs are needed to increase the skills and confidence of persons with lived experience to approach and work with researchers. Engage advocates to develop and implement training. (Hall, Kluger)

- A complementary need exists for training programs to improve the skills and openness of researchers to foster optimal collaborations with patients, families, and other stakeholders. (Kluger)

- Channels are needed for persons with lived experience to raise research questions and find collaborators. (Kluger)

- Care partners, with their unique perspectives, expertise, and significant lived experience, need to be recognized and included as part of the care team in both clinical care and research. (Sumrall)

- Care partners need attention and support as individuals and second-order patients, not simply as care partners. (Sumrall)

- When engaging in research targeting health care provider practices (e.g., primary palliative care), it is important to include health care providers as advisors to ensure that the proposed intervention is feasible, acceptable, and meaningful to end users. (Kluger)

- It is important to partner with nonprofits because they provide key resources to their communities, have outstanding reach that can accelerate implementation and dissemination efforts, and possess unique perspectives and expertise on systems, policy, communication, and community. (Kluger)

- Relationships with people living with serious illness in and out of the clinic are crucial to inform research priorities and questions and teach researchers how to do their jobs better. (Kluger)

- When involving patients, care partners, clinicians, or other partners in implementation or dissemination research projects, it is important to identify one or more local champions. (Hall, Kluger, Yarab)

- Recognize that involving patients in research provides them with meaning during their serious illness journey and the opportunity to improve the care and lives of others. (Sumrall)

- To engage with people who are not normally involved in research, take advantage of the connections and relationships that community partners have built over time and have experts and representatives of those communities help design programs that are culturally relevant and meaningful. (Yarab)

- Establish standing lived experience panels for research studies. (Bennett)

- Conversations with real people reveal nuances that are not always clear when collecting data from electronic health records (EHRs) or claims. (Mor)

Addressing Gaps in Research Methodology/Study Design

- Qualitative and mixed methods research are crucial tools to improve care for people with serious illness. (White)

- When evaluating complex interventions to improve serious illness care, rigorous plans are needed to monitor and maintain intervention fidelity because of its impact on interpreting both positive and negative trials. (White)

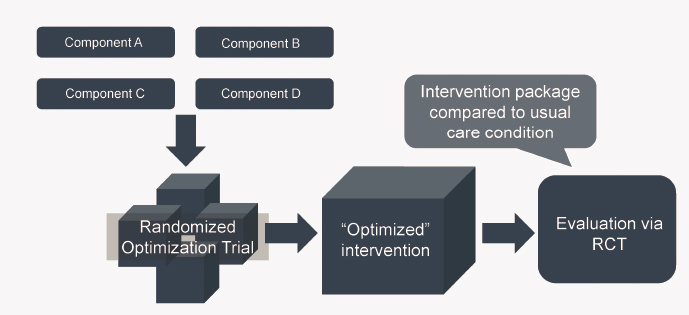

- Factorial trial designs provide an efficient method for determining which intervention components are effective. (Odom)

- The multiphase optimization strategy is a key approach to addressing the challenge of identifying the effective components of a serious illness care intervention. (Odom)

- Given that most people with serious illness are not seen in academic medical center settings, it is important to focus research efforts on multisite, nonacademic settings to see what works in “the real world.” (Jacobson)

- Encourage quasi-experimental research trial designs with the idea of leveraging features of the natural world and environment to mimic randomization and attempt to get close to causal inference using real-world evidence and data. (Jacobson)

- To narrow the evidence gap about palliative care, consider evidence from other countries, where adoption is high. (Jacobson)

- To determine if payment is a key barrier to palliative care, consider analysis in settings such as the Department of Veterans Affairs, where incentives should be better aligned to promote value. (Jacobson)

- Rather than asking if palliative care saves money, consider whether it brings value (e.g., benefits outweigh the costs). (Jacobson)

- Incorporate Bayesian statistical methods into studies. (Colborn)

- Reduce missing data and rethink which outcomes to target on the causal pathway. Design studies to mitigate missing data and incorporate data collected through routine care. (Colborn)

- When working with observational data, ensure that you are able to test the hypotheses and the results will be generalizable to the population of interest. (Colborn)

- Engage in more cross-disciplinary collaborations with computer scientists, psychometricians, and biostatisticians who work regularly with EHR data and clinical notes. Recognize the value of having statisticians training and mentoring along with serious illness care researchers. (Colborn)

- More data coordinating centers are needed to help engage rural communities and hospitals that do not have sufficient in-house biostatistics capacity. (Colborn)

- Include community-engaged research that involves community members, patients, and families in designing a study and interpreting and disseminating results. (Odom)

- Recognize that pragmatic trials in serious illness care are complex multicomponent transitional care interventions; core functions must be specified, tracked, and maintained with integrity. (Grudzen, White)

- Mixed methods are needed to identify how, why, when, where, and in whom the intervention will work. (Grudzen, White)

- Bring the voices of nonacademic partners (e.g., home health organizations or hospice agencies) into the design and conduct of pragmatic trials for the study to have greater impact. (Grudzen)

Addressing Gaps in Outcome Measures/Data

- Invest in targeted instrument development to advance serious illness care research. (Bennett)

- Informative research studies require high-quality, valid, and reliable outcome measures that can capture the experiences of all U.S. cultural and socioeconomic groups. (Bennett)

- Recognize that serious illness care research includes many topics relevant to end-of-life care for which outcome measures either do not exist or are not validated or sufficiently rigorous, including for financial hardship for patients and families. Such measures are necessary for developing program and policy interventions tailored to the specific challenges people are facing. (Bennett)

- The evolving technology landscape can provide new opportunities for collecting patient- and care-partner-reported data. (Bennett)

- Be cognizant of the strengths and limitations of a dataset, particularly for secondary data analysis. This includes who is eligible for the study, who participated, what the questions were, and if they were relevant to these priority populations. (Bennett)

- Recognize that measures for patient preferences exist but are focused heavily on treatment and so do not cover the broader range of preferences, such as whom they want to be with and where and how they want to spend their time. (Mack)

- Focus on filling significant measure-related gaps, including the need for robust measures for patient goals, decision making, and concordance of care. (Mack)

- Recognize that available measures are often not tested for responsiveness to change, important information for assessing health care interventions, and not suitable for use across the lifespan. (Mack)

- Addressing measures gaps is important because a lack of robust, validated measures useful for understanding patient goals and values is a significant limitation to progress in the field that creates challenges for developing interventions, attaining funding, testing intervention efficacy, and making comparisons across studies and constrains the extent to which the patient voice is heard in palliative care research. (Mack)

- Focus on developing measures for what matters and ensure that what we are measuring is what we think the intervention is impacting. (Kutner)

- Methods are needed to optimize proxy reports, given that proxies are not very good at accurately reporting what a patient is experiencing. (Mack)

- To have a set of robust measures recommended for use, patients and care partners need to be involved in every step of development, including prioritizing needed domains. (Mack)

- Academia has a key role to play in developing quality metrics for accountability purposes. (Lane-Fall, Unroe)

- A common taxonomy of spirituality is needed. (Steinhauser)

- Much more work is needed to refine the design of studies and measurements, to identify the specific domains of spirituality researchers are interested in and to ensure that a measure that taps into that domain of interest is selected for the study. (Steinhauser)

- More work also is needed to identify a common core set of measures and create a working group to set that common core set. (Steinhauser)

- Embrace population and cultural diversity and the growing population that considers themselves neither spiritual nor religious across the range of questions that get to the roles, beliefs, and practices around spirituality. (Steinhauser)

- The field needs to focus on developing quality measures for the highest-risk, most vulnerable populations and ensuring they are incorporated into the Medicare Advantage star ratings. (Meier)

Integrating Health Equity into Serious Illness Care Research

- It is essential to center equity at the beginning of the research design process, unmute diverse voices, engage unique and diverse voices and perspectives, and approach research design through an equity lens. (Bakitas, Kutner)

- To engage in research to better understand how to remediate disparities, consider incorporating social workers into research teams. (Bullock)

- Change the way we communicate by “breaking the script” by asking questions differently; for example, rather than asking patients if they are married, ask them to identify the biggest support in their life and if they live with anyone. Ask who needs to be in the room when discussing care options. (Candrian)

- Consistently ask patients about sexual and gender identity in a way that makes them feel safe and include the data in research. (Candrian)

- Meet people where they are when designing studies, be flexible, and use icebreakers appropriate for specific communities to start a conversation. (Bullock)

- Engage communities with humility, involve the community at every stage of research, and let the community know that the study aims to improve the way they receive care. (Bakitas, Bullock, Candrian, Davila)

- Advance equity by conducting research that engages with all the voices of rural communities. (Bakitas)

- Consider a hub-and-spoke model for research dissemination in rural areas. (Bakitas)

- Recognize that minoritized communities do want to participate in clinical trials. (Winn)

- To expand the diversity of clinical trial enrollees, train recruiters in appropriate communication skills and emphasize that a clinical trial is both an experiment and an extension of health care that improves the standard of care. (Winn)

- It is critical to focus on an individual’s zip code (their ZNA) in addition to biology and race to understand how individuals interact with the health care system and why health outcomes vary among different populations. (Winn)

- Enroll research participants from emergency departments, which will generate a more diverse population than at a major academic center clinic. (Grudzen)

- For research to be applicable to under resourced communities, targeted efforts are needed in the initial stages to capture, integrate, and respond to their lived experience. (Kluger)

- Address the fact that many existing measures are often not adapted culturally or available in multiple languages suitable for use with a wide range of populations. (Mack)

- Incentivize including the voices of children, individuals with cognitive impairment, and people from a range of underrepresented cultural backgrounds in research studies. (Mack)

- Integrate underrepresented populations who do not trust the system or clinical trials in research as experts and not tokens. (Kirch)

- Developing interventions to address inequities requires identifying gaps in what is known about beneficiary experiences and using mixed methods to understand how the current system affects racialized, marginalized, and underserved populations. (Meier)

- Ensure research is equity centered; make equity the North Star. (Kutner, Meier)

- Mixed methods research is a critical mechanism for improving equity in research outcomes. (Robinson-Lane)

- Researchers need to emphasize the impact of the profit motive in Medicare Advantage plans and the danger of amplifying longstanding inequities. (Meier)

- Ensure research considers all voices, including children and adolescents, individuals with limited literacy or limited English proficiency, and those who require proxy reports because of their age, cognitive disability, or critical illness. (Mack)

- Include as diverse a group of patients and families as possible from the start of a project; this can provide a perspective that helps develop the capacity to scale and have optimal impact and relevance. (Bartels, Lane-Fall)

- The key to developing interventions that reduce disparities is to start by centering equity and using human-centered design that brings in minoritized populations to help design the study. (Lane-Fall, Odom, White)

- Achieving equity-focused implementation of interventions requires focusing on reach and equity from the beginning. Designing and selecting interventions for complex conditions and needs and low-resource communities requires implementation strategies that are scalable, sustainable, and able to reduce inequities in care and use an equity lens for outcomes. (Bartels)

- To understand the pain points for under resourced systems, start by asking questions about what services they wish they could provide and how you can partner with them to address some of their challenges. Be willing to adapt or pivot if what you hear is different from what you expect. (Bakitas, Lane-Fall)

- Recognize that it is difficult to approach questions of equity when you do not have Medicaid beneficiaries involved in a study or when safety net hospitals and other under resourced institutions do not have the funds to invest in interventions. (Siu)

Advancing Implementation Science

- Study designers should start with scalability, sustainability, and implementation when developing interventions; employ user-engaged and user-centered design principles from the beginning; and think beyond effectiveness as an outcome. (Bartels, Lane-Fall, Siu)

- Recognize that fidelity to function is critical and serves as the mechanistic link between the intervention and the outcome. (Lane-Fall)

- Establish interdisciplinary collaborations and partnerships with industry to test interventions and impact care in nursing homes. (Unroe)

- Include human systems engineers and someone with deep expertise in qualitative and mixed methods who can ask questions that will deepen the impact and add nuance to a research project. (Lane-Fall)

- Be humble, and recognize that clinicians, patients, and end users bring invaluable perspectives and experiences to optimizing interventions above and beyond the developers’ intent. (Bartels)

- Develop an intervention that works, then figure out how to get it into practice. (Unroe)

- Ensure rigor and structure behind adaptation and hold oneself accountable to the core elements of an intervention; collect data on the effect of an adaptation to add to the evidence base. (Lane-Fall, Siu)

- To balance the need for fidelity and adaptation when implementing an intervention, listen to engaged partners but realize you cannot do all that is asked of you. Carefully document research team decisions to include or exclude a feature to enable continued learning about the implementation. (Unroe)

- Include funds to support community-based organizations’ participation in implementation projects. (Hurley)

Developing the Research Workforce

- To build a pipeline of investigators, ensure that programs offered at academic centers cover the breadth of methodological expertise, including qualitative methods, Bayesian methods, and pragmatic trials; the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Clinical and Translational Science Awards are a good example. Many medical centers now offer advanced degree programs in clinical research that would benefit palliative care researchers. (White)

- Recognize that serious illness care research is team-based science, and it needs a community that grows young investigators, allows them to have collaborators, and provides them with the skills needed to conduct and manage complex trials at multiple trial sites. (Odom)

- To develop a new generation of research scientists, major barriers to academic promotion need to be addressed, including the lack of recognition/reward for quality improvement research and new metrics for promotion and tenure that recognize the value of individuals involved in such research and the impact of their work on the field. Similarly, time invested in community engagement needs to be considered in academic advancement. (Bartels, Lane-Fall, Meier, White)

- Early-stage researchers need to think creatively about how they can partner with someone in business school or experts in behavior change and take advantage of the “open landscape to innovate, partner, and grow in whatever direction they want.” (Kelley)

- To enable researchers to contribute and feel most successful, they need to pick a subject about which they are most excited and passionate. (Kelley, Meier)

- In thinking about the growth in the field and the need to bring in more diverse perspectives and life experiences, one approach might be to include high school students in summer research projects, which might encourage them to pursue a career in palliative care, nursing, social work, or community health work, all of which would benefit the field. (Kelley)

- Consider opportunities focused on early-stage researchers and for K–12 science teachers, undergraduates, postdocs, and medical residents to participate in research. An important funding mechanism is the diversity supplement attached to current grants that can be used for individuals at any educational or career stage. (Kelley)

- Consider programs such as the National Institute on Aging’s Start-Up Challenge, which is designed to train and promote the work of early-career entrepreneurs from a wide array of diverse backgrounds by providing mentors, coaches, and resources to apply research to the problem they want to solve. (Kelley)

Additional Suggestions to Improve Serious Illness Care Research

- Research should include the entire lifespan, span multiple diseases—investigators will have to leave their silos—and be interdisciplinary to account for factors such as who pays for care that can influence and improve care. (Kelley, Morrison)

- Research needs to consider multiple partner perspectives across the lifespan, across care settings, and from the community to home to a more societal level. (Bakitas, Bartels, Grudzen, Kutner, Odom, Unroe, White)

- Focus on research that will bring immediate impact while planning for the long game; ensure sustained support for serious illness care science so that we can continue this work over the long term. (Kutner, Morrison)

- Research teams need to be interdisciplinary. (Colborn, Kutner, Lane-Fall, Odom, White)

- The goal of research is to make an impact. (Kutner)

- Focus on the goal of research as improving quality of life. (Kutner, Morrison)

- Researchers need to work with larger nonprofit organizations and coalitions that have the ability and skills to influence policy. (Meier)

- Given that much of serious illness care research takes place outside formal palliative care programs, research communities need to consider how to create bridges across specialties (e.g., oncology, primary care, neurology) and disciplines (e.g., medicine, nursing, chaplaincy, social work) to support these investigators. (Kluger)

INTEGRATING LIVED EXPERIENCE INTO SERIOUS ILLNESS CARE RESEARCH

Benzi Kluger, the Julius, Helen, and Robert Fine Distinguished Professor of Neurology and Medicine and director of the Palliative Care Research Center at the University of Rochester Medical Center, opened the first session by recounting what he referred to as his “accidental journey” into palliative care. Once he began seeing patients after completing his training as a clinician and researcher, he began to hear heartbreaking stories from them, leaving him feeling helpless and hopeless. “I was not prepared for that in my training,” explained Kluger. “I think the rule in medicine is that you want to have a professional distance,” Kluger noted. He shared, however, that he was lucky to have a mentor—workshop Co-Chair Jean Kutner—who encouraged him to follow his heart (Kluger, 2018). Over the next 2 years,

- Recognize that it is possible to do rigorous quality improvement work to address current issues and generate evidence to inform the field at the same time; these two facets need to be linked more clearly. Researchers need to publish quality improvement results in the peer-reviewed literature and improve clinical practice based on emerging evidence. Opportunities exist with current data and real-world data applications for artificial intelligence, which can power natural experiments that can influence policy. (Kelley, Kluger, Kutner)

- Consider data pooling to help nursing homes adopt the concept of a learning health care system. (Mor, Unroe)

- The serious illness care field could learn much from business schools about implementation and scale. (Meier)

- A journal of mixed methods would be helpful for the field. (Grudzen)

- To increase the likelihood of a paper being accepted for publication in the best journal possible, make sure to cite the NIH stage model and also that the authors followed the appropriate framework for qualitative research. (White)

- In order to do rigorous science, ensure that researchers have methodologic expertise in the topic in addition to advanced degrees. (White)

NOTE: This list is the rapporteurs’ synopsis of suggestions made by one or more individual speakers as identified. These statements have not been endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. They are not intended to reflect a consensus among workshop participants.

Kluger listened to and communicated in a new way with patients, and that experience was almost like a third fellowship for him. “Patients and their families taught me what really matters and taught me a lot about how I could be a better doctor for them,” explained Kluger. He shared three key lessons from this experience:

- Clinical researchers need encouragement, community, and practice to follow their hearts.

- Relationships with people living with serious illness in and out of the clinic are crucial to inform research priorities and questions and teach researchers how to do their jobs better.

- Clinical innovation and quality improvement can drive high-quality research.

Motivated by a vote of patients and families at the 2010 World Parkinson’s Congress, Kluger organized the first international working group on palliative care and Parkinson’s disease (Kluger et al., 2017). The working group’s first meeting, funded by a grant from the Parkinson’s Foundation, identified gaps in the serious illness care field and developed an ambitious road map that the field is still following today. Kluger credited the patients and families who participated in the meeting as critical to its success (Hall et al., 2017). Kluger specified that “it was not just respect for people living with serious illness, it was parity of esteem that made their input possible. They were very much the experts and, in fact, were more of an expert in a lot of ways than I was.”

A Patient’s Perspective

In 2013, Kirk Hall, an individual living with Parkinson’s disease, advocate, author, and speaker, was working on a book about his experience with Parkinson’s-related cognition issues (Hall, 2013). In the chapter on palliative care, he questioned whether it is possible for doctors to properly advocate for patients whom they do not know well. Hall urged clinicians to have a frank discussion with their patients to learn what is important to them and their family and explain care options. Kluger and Hall had ongoing discussions about integrating the patient experience into research. Their collaboration led to the development of “a model that included patient and care partner issues at all stages of the disease starting at diagnosis,” explained Hall.

Hall suggested that the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) fund research on palliative care for Parkinson’s disease. Hall and Kluger wrote a grant that funded a 3-year multisite study demonstrating the value of such care (Kluger et al., 2020). Since then, there have been two international conferences on palliative care and Parkinson’s disease, a presentation Hall made at the 2016 World Parkinson’s Congress, and a follow-up study on training and implementing palliative care for Parkinson’s disease at the Parkinson’s Foundation Centers of Excellence. A new Community Outreach and Patient Empowerment program on Parkinson’s disease is under development to increase awareness and availability of palliative care.

Hall offered suggestions for moving the field forward:

- support efforts to build awareness and facilitate expanding palliative care for Parkinson’s disease and neuropalliative care,

- proactively identify individuals for advocacy training,

- engage current advocates to develop and implement training, and

- brainstorm new ideas.

Hall also noted the importance of removing barriers to including music and vocal therapy groups in palliative care programs.

Kluger highlighted the lessons he took away from Hall’s presentation:

- No one knows a serious illness better than the person living it.

- People living with an illness know the real urgency and importance of improving care.

- Patients improve research when treated as experts.

Kluger pointed out that care partners are the least supported and most important members of a care team (Prizer et al., 2020). His team surveyed care partners about how much time they spend providing care, and one respondent said she was working up to 100 hours a week providing care for her loved one. “Having a care partner improves quality of life and improves outcomes for people with Parkinson’s and other serious illnesses,” observed Kluger. Given their key role, Kluger reiterated the importance of involving care partners in research.

A Care Partner’s Perspective

Malenna Sumrall, a patient care partner for her husband and caregiving advocate based at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, recounted that when she met Kluger late in her husband’s Parkinson’s disease journey, he was the first doctor in 14 years who asked how she was doing. “It was toward the end of my husband’s life, and the palliative care was just so valuable to us in so many ways. It made me a passionate advocate for palliative care,” she shared. Having served on two PCORI-sponsored advisory councils and with a Ph.D. in educational research, Sumrall explained that she found it interesting to be involved in research as a care partner rather than as a researcher. She was impressed that the projects Kluger and his colleagues were conducting included both qualitative and quantitative components. “It made me realize that the researchers wanted the data to be as rich and as informative as possible,” she said.

Sumrall was also impressed by how highly the researchers valued input from advisory council members. At one council meeting, an individual with Parkinson’s disease mentioned how he always tried to do his best physically at medical appointments; as Sumrall explained, “that led to the concept of ‘holding back,’” which then became an area of investigation in

the research project. As part of that same project, the research team heard from patients and care partners how much they needed to talk to others who understood what they were going through. That led to creating a peer navigator program as part of Kluger’s clinic at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Center. Sumrall also started a Zoom support group for care partners. “I realized they do not have the time necessarily to go someplace for an hour or two,” explained Sumrall. “This gave them the flexibility to join in as much as they could.”

Sumrall said that working with care partners has helped her contribute more than just her own experiences and perspective. “I have the voices of others when I participate,” she said. Her volunteering, she added, is her way of contributing to help others. “It is also the best way I can honor my husband. He was a social work professor whose passion in life was helping others, and that is what I hope I am doing now.”

Kluger summarized lessons learned from Sumrall’s presentation:

- Care partners need to be recognized and included as part of the care team in both clinical care and research.

- Care partners have unique perspectives, expertise, and unbelievable amounts of lived experience.

- Care partners need attention and support as individuals and second-order patients in addition to care partners.

Kluger underscored that “PCORI does an amazing job in terms of including people with lived experience and other partners in every aspect of the research journey, from finding out what we should be researching, the agenda, and the evaluation process.” He credited PCORI’s rubric with helping him design an effective engagement plan and changing how many investigators approach research to think about things more pragmatically. Kluger said that he establishes patient and advisory councils for all his projects and advises his mentees to do the same.

Kluger credited PCORI, Hall, Sumrall, and the Parkinson’s Foundation for supporting a randomized comparative effectiveness trial showing that palliative care improved patient and family outcomes more than standard care (Kluger et al., 2020). The research grew directly from his clinic work, and he pointed out that it was successful because of the role the project’s partners played in developing the consent form, engaging participants, and choosing outcomes. They “helped us make better decisions, which helped it be a positive trial as opposed to what we see a lot of, which are negative trials of good palliative care interventions,” emphasized Kluger.

Building on the trial’s results, Kluger and his collaborators worked to integrate palliative care into the Parkinson’s Foundation Centers of Excellence network. Kluger noted that as a result of the key dissemination role played by the foundation, 33 of 34 academic sites he approached have joined the implementation project.

The Parkinson’s Foundation Perspective

Nicole Yarab, vice president for clinical affairs and information and resources at the Parkinson’s Foundation, has worked as a neurology nurse and cared for patients in a multidisciplinary amyotrophic lateral sclerosis clinic. Based on her clinical experience, she advocated for implementing palliative care across the foundation’s Centers of Excellence network. She explained that this work aligns with the foundation’s ethos of putting people with Parkinson’s disease and their care partners first through true patient engagement.

Yarab pointed out that when involving patients and care partners in research, it is important to identify a project’s champions. The power of partnering with a nonprofit, according to Yarab, lies in its connections and resources. The foundation has the trust of the Parkinson’s community and many ways to reach people on a broad basis through its global care network. Yarab has used her position in the organization to champion the implementation effort and alert people about its importance in delivering quality care and improving people’s lives.

In addition to identifying champions, another important aspect is regular meetings with its People with Parkinson’s and Care Partner Advisory Councils and clinician advisors. Collaboration, in Yarab’s view, is part of the “magic sauce.” “This is not something the foundation would have been able to do by itself,” she said, “and I do not think the community can do this work by itself, but if we put all our powers together, we are able to make a real impact.”

Reflecting on Yarab’s presentation, Kluger underscored the importance of working with people who are passionate and know how to get things done. He summarized the lessons learned from working with the Parkinson’s Foundation, noting that nonprofits

- provide key resources to their communities, yet researchers often overlook them as partners;

- have outstanding reach and can accelerate implementation and dissemination efforts; and

- possess unique perspectives and expertise on systems, policy, communication, and community.

Expanding Access to Palliative Care

Kluger distinguished between implementing programs in academic settings and bringing palliative care to the broader population. To take on the challenge of broader dissemination, Kluger secured grants from the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR) for a project to train community neurologists on the basics of palliative care, which they would otherwise not learn. It also relies on telemedicine to provide chaplains, social workers, pharmacists, and other resources to neurologists in rural areas (Kluger et al., 2024). Noting high rates of burnout among neurologists, Kluger pointed out that the project is also trying to improve the lives of community health providers in addition to patients and care partners (Brashear and Vickrey, 2018).

Kluger highlighted that a key lesson has been fully appreciating how much health care providers are interested in improving care. “They are very busy people and do not have time to be part of clinical trials, but they were honored to be part of this one because they wanted outcomes to be better, they wanted to learn palliative care, and they wanted to get social work, counseling, and other services for the people they serve,” said Kluger. One neurologist said that he valued being part of the study because he felt less alone in caring. “It is frustrating that we have to work so hard against the system to care for patients, and it can feel very isolating,” observed Kluger.

Another lesson, noted Kluger, is that researchers can create alignment by co-learning and collaborating on identifying systems’ issues and solutions. He added that the research team is working with Hispanic communities in Rochester, NY, to learn about their lived experiences so they can translate this model effectively for those communities.

Kluger offered several key reflections and suggestions:

- Research questions, priorities, and outcomes must come from thoughtful collaboration with people with lived experience, including patients, family carers, and other key partners.

- Principles of parity and respect should be part of all aspects of collaborative research with lived experience experts.

- For research to be applicable to underserved communities, additional efforts are needed to capture their lived experience.

- Early career support and community is needed for researchers interested in serious illness care and palliative care.

- Training programs are needed to increase the skills and confidence of persons with lived experience to approach and work with researchers.

- A complementary need exists for training programs to improve the skills and openness of researchers to foster optimal collaborations.

- Persons with lived experience need to have ways to raise research questions and identify collaborators.

- Dissemination plans must consider real-world impact and involve influential community partners, including nonprofits.

Audience Q&A

Kathleen Unroe, associate professor of medicine at the Indiana University School of Medicine and research scientist at the Indiana University Center for Aging Research, asked panelists for ideas on how to include the perspective of and recruit residents in nursing homes and their care partners into research efforts. Sumrall noted that in all settings including nursing homes, it is important to include people who are willing to express their opinions, make them feel comfortable doing so, and have as much participant diversity as possible. Hall said that based on his experience, individuals who are engaged and have meaningful questions and input at support group meetings generally are the type of people researchers would want to include. He added that it is helpful to know the other activities potential advocates are involved in because that provides clues as to what they might bring to the table.

Rebecca Aslakson, professor and chair of the Department of Anesthesiology at the University of Vermont Larner College of Medicine, said that the hardest thing about palliative care research is not finishing the journey one takes with an individual because of that person’s disease. Noting that she feels that research is a patient’s legacy, she asked panelists how to innovatively involve people who may be able to start but not finish it. Hall replied that this is difficult, particularly when people are not getting the help they need. Sumrall said that it is important to realize that involving people in research provides them with some meaning. “You are giving them the opportunity to make lives better for other people, and that is really powerful,” she said.

Kathryn Pollak, professor of population health sciences at Duke University School of Medicine and member of the Duke Cancer Center, asked panelists for their thoughts on how to make research participants feel comfortable when they come from such different life experiences. Kluger added another layer to that question by noting that Parkinson’s disease affects people with different levels of cognitive ability to accommodate and

people from diverse populations. For people with cognitive difficulties, he sends out a meeting agenda and questions in advance, so they have time to consider the questions. Given the importance of parity of esteem, it is key to elevate the ideas of every participant; find what was wise, courageous, and compassionate in what they said; and incorporate their ideas into research. “If you are able to do that consistently, you create a culture and a family where everybody feels safe and welcome,” said Kluger.

Deborah Swiderski, attending physician and associate professor of medicine and family and social medicine at Montefiore Einstein, asked Kluger to elaborate on his ideas regarding training. Kluger replied that the Parkinson’s Advocates in Research program conducts training programs for patients and care partners who want to be involved in research. More remains to do, however, to engage people from underserved communities who are not at academic medical centers to enroll in the program. Kluger pointed to his work with Community Health Ministries to develop a train-the-trainer program. He emphasized that the goal is to get people to see themselves as experts and understand they have a great deal to contribute. Yarab added that the Parkinson’s Foundation works with community partners and its Centers of Excellence to engage with people who are not normally involved in research. The key is to take advantage of the connections and relationships its partners have built and have experts and representatives of those communities help design a program that is culturally relevant and meaningful.

Charlotta Lindvall, assistant professor of medicine and Director of Clinical Informatics, Dana Farber Cancer Institute, noted that the oncology community is developing centralized websites where researchers can reach out to diverse populations to enroll in clinical trials and wondered whether there were similar websites to enable patients and their care partners to engage in research. Kluger responded that one of the wonderful aspects of the Parkinson’s community is that care partners are recognized and embraced. He noted that the Michael J. Fox Trial Finder3 provides that capability, and the Parkinson’s Foundation was part of a study his group conducted that enrolled patients and care partners. Yarab added that the foundation offers other opportunities to reach care partners through its annual Care Partner Summit, helpline that provides connections to a variety of services and programs, and weekly offering through the Parkinson’s Disease Health at Home program.

___________________

3 Additional information is available at https://www.michaeljfox.org/trial-finder (accessed March 16, 2024).

EXPLORING THE STATE OF THE SCIENCE OF SERIOUS ILLNESS CARE RESEARCH:

PAST, CURRENT, AND FUTURE

Sean Morrison, Ellen and Howard C. Katz Professor and Chair of the Brookdale Department of Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine and director of the National Palliative Care Research Center (NPCRC) at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, reminded participants that the goal of developing the evidence base is to appropriately care for, relieve suffering, and improve the quality of life for people living with serious illness and their loved ones. He shared the definition of serious illness as “a health condition that carries a high risk of mortality and either negatively impacts a person’s daily function or quality of life or excessively strains their care partners” (Kelley and Bollens-Lund, 2018).

Morrison pointed out that people often conflate palliative care and serious illness. “Serious illness is the population who we are attempting to care for. Palliative care is a delivery system by which we care for that population, and palliative care is beneficial at any stage of a serious illness,” he explained. Morrison referred to the definition of palliative care developed by the National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care (2018)4:

an interdisciplinary care delivery system designed to anticipate, prevent, and manage physical, psychological, social, and spiritual suffering to optimize quality of life for patients, their families and care partners. Palliative care can be delivered in any care setting through the collaboration of many types of care providers. Through early integration into the care plan of seriously ill people, palliative care improves quality of life for both the patient and the family.

Morrison highlighted three key events in the United States in the mid-1990s that focused attention on the inadequate care provided to people with serious illness. The first was the AIDS epidemic; on average, a person living with AIDS experienced 17 symptoms daily, about twice as many as someone with metastatic cancer, and many were marginalized, with no effective treatments for the disease or to manage symptoms.

The second event was the emergence of the assisted suicide movement led by Dr. Jack Kevorkian. Morrison pointed out that its growth underscored the poor quality of care provided by the U.S. health care system, as individuals preferred to end their lives rather than experience the care provided in hospitals at the time.

The third event was the publication of the results of the Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of

___________________

4 For more information, see https://www.nationalcoalitionhpc.org/ncp/ (accessed January 5, 2024).

Treatments trial (SUPPORT Principal Investigators, 1995). The trial enrolled 9,000 patients at five of the top-rated U.S. teaching hospitals; 50 percent of them experienced moderate to severe pain over half the time before they died, and 40 percent spent the last 10 days of their lives in an intensive care unit (ICU) on a ventilator or in a coma. “That was the state of care for people with serious illness in the mid-1990s,” observed Morrison.

Turning to the topic of funding research to improve the quality of life for people with serious illness, Morrison pointed out that the National Institutes of Health (NIH) awarded 64 grants in 1995 (24 were educational rather than research), totaling slightly more than $9 million, which represented 0.069 percent of total NIH funding. Morrison referenced Amy Berman of the John A. Hartford Foundation, who frequently pointed out that “0.069 rounds to zero.”

Morrison explained that as of the mid-1990s, only 719 U.S. hospitals—15 percent of all U.S. hospitals—reported that they offered “end-of-life care services.” Five palliative medicine fellowship training programs, each graduating approximately two fellows a year, existed in 1997. That year, Morrison explained, the Institute of Medicine5 released the first of six reports on end-of-life care, which concluded that most people with serious illness experience inadequately treated symptoms, fragmented care, poor communication with clinicians, and strains on care partners and support systems (IOM, 1997). The report also concluded that

- legal, organizational, and economic obstacles obstruct reliably excellent palliative care;

- education and training of health care professionals fail to provide the necessary knowledge and skills required to care for the seriously ill; and

- the knowledge base is inadequate to support evidence-based palliative care clinical practice.

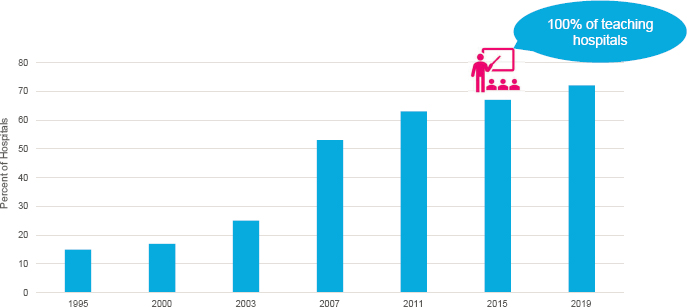

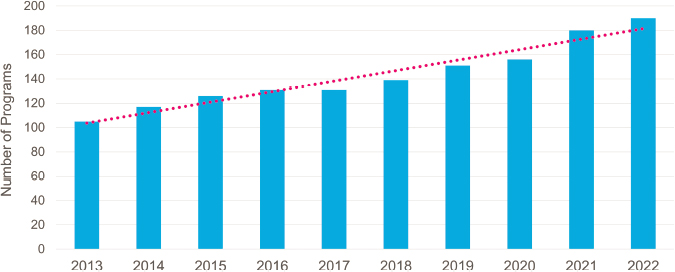

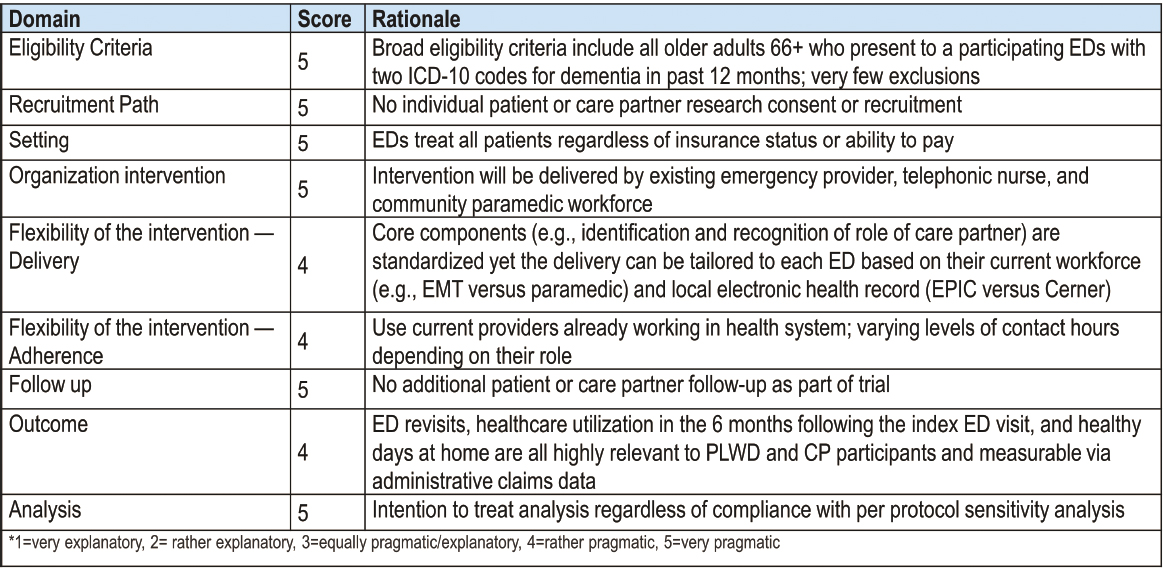

Tracking the growth in palliative care throughout the ensuing two decades, Morrison pointed out that 100 percent of U.S. teaching hospitals had a palliative care team in 2015, and by 2019, more than 70 percent of all U.S. hospitals had palliative care teams (see Figure 1). Morrison added that by 2020, nearly 85 percent of hospitals had palliative care teams. As of 2022, there were more than 180 palliative care fellowship slots available in the United States (see Figure 2) and almost 8,000 board-certified palliative medicine physicians (see Figure 3).

___________________

5 As of March 2016, the Health and Medicine Division of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (National Academies) continues the consensus studies and convening activities previously carried out by the Institute of Medicine (IOM). The IOM name is used to refer to reports issued prior to July 2015.

SOURCES: Morrison presentation, November 2, 2023; created using data from the Center to Advance Palliative Care and National Palliative Care Research Center.6

SOURCES: Morrison presentation, November 2, 2023; created using data from the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine and the National Resident Matching Program.7

___________________

6 The National Palliative Care Registry, a joint project of the Center to Advance Palliative Care (CAPC) and the National Palliative Care Research Center (NPCRC), was active from 2008-2020, and its goal was to build a profile of palliative care teams, operations, and service delivery. In fall 2020, a national registry for the collection of palliative care data launched. The National Palliative Care Registry™, the Palliative Care Quality Network (PCQN), and the Global Palliative Care Quality Alliance (GPCQA) united into one national system called the Palliative Carer Quality Collaborative (PCQC) available at https://www.palliativequality.org (accessed July 1, 2024).

7 See https://aahpm.org/fellowships/match and https://www.nrmp.org/match-data-analytics/fellowship-data-reports/ (accessed July 1, 2024).

SOURCES: Morrison presentation, November 2, 2023; created using data from the American Board of Medical Specialties.8

The growth of palliative care did not happen by accident, emphasized Morrison, but was a result of a sustained strategy. First, unlike any other field of medicine, philanthropy built this field. Morrison pointed to early funders, such as the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and Open Society Foundation, along with many others, that spent over $250 million to build the field and develop the evidence base that palliative care improves care for people living with serious illness.

Morrison highlighted the key contributions of George Soros, who funded the Project on Death in America (PDIA)9 in 1995, an initiative conceived to create the PDIA Faculty Scholars Program. The program developed leaders in U.S. academic medical centers to build the field by leveraging a small amount of money to install pillars in these centers because that is where the nation trains its health care professionals and researchers conduct the studies needed to advance the field. “When we reflect back, we owe a huge debt of gratitude to private sector philanthropy in this country, for this would not have happened without both commitment and their vision,” Morrison said.

Morrison explained that Diane Meier originally developed a strategy to advance the field of palliative care focused on three key areas: improving education and training, becoming a recognized specialty through board certification, and building the evidence base. The strategy featured both a top-down and bottom-up component, each reinforcing the other.

___________________

8 See https://www.abms.org/ (accessed July 1, 2024).

9 For more information, see https://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/publications/transforming-culture-dying-project-death-america-1994-2003 (accessed January 18, 2024).

The top-down strategy called for creating a supportive environment using the media, advocacy, public awareness, accreditation, regulation, and payment. The bottom-up strategy involved developing an evidence base, enhancing the workforce, and increasing the number and quality of palliative care programs.

Morrison described how the research effort proceeded according to a set of guiding principles, starting with creating a unified scientific community that brings researchers together to work collaboratively, with a shared vision, to maximize the use of existing resources. The second principle was to align research with the prevailing scientific culture and infrastructure. “The field of science is very conservative, and you do not get very far if you are way outside,” explained Morrison. “You have to belong to the culture.” As an example, he described framing his first NIH grant proposal around hip fractures and not palliative care and pain relief because at the time, the National Institute on Aging (NIA) had a focus on hip fractures. Thus, he was able to conduct the research he wanted because it aligned with NIA’s funding interests.

The third principle was to focus on what is scalable, has low unit costs, and reduces opportunity costs without reinventing the wheel. “We were too small a field at that time for everybody to be doing the same thing over and over and over again,” said Morrison. The final principle was to create long-term sustainability because, despite the incredible investment philanthropy had made to jump-start the field, philanthropic dollars are scarce, and funders can change their priorities.

Morrison pointed out the common misperception that NIH is the primary funder of biomedical research. In reality, industry sponsors two-thirds of it, most of that allocated to developing drugs and devices (see Figure 4) (Teconomy Partners, 2022). Morrison noted that only 10 percent of industry spending goes to health services research, whereas 76 percent goes to biopharmaceuticals.

NIH accounts for nearly 80 percent of federal funding on biomedical research. “If you work through all those percentages, we compete for about 9.5 percent of all industry funding,” explained Morrison. “If you look at philanthropy, we are competing for about 1.2 percent of total funding, and if you look at NIH, we compete for about 20 percent of NIH funding.”

Morrison pointed out that a key milestone was the 1997 workshop on end-of-life care convened by Patricia Grady, the director of NINR. This led to the NIH director establishing the NINR Office of End-of-Life and Palliative Care Research, which served as a home for research on people with serious illness for more than two decades.

SOURCES: Morrison presentation, November 2, 2023; Teconomy Partners, 2022.

To develop a road map and strategy for research, NINR’s Office of End-of-Life and Palliative Care convened a state of the science conference focused on the needs of people with serious illness. The recommendations developed during this meeting included the following:

- Create a network of investigators and well-defined cohorts of patients to facilitate coordinated interdisciplinary, multisite studies.

- Explore public–private partnerships related to end-of-life research support.

- Enhance training of a new generation of interdisciplinary scientists.

A confluence of personal and foundation interest led to establishing NPCRC at Mount Sinai, where the Center to Advance Palliative Care (CAPC) was located. Morrison said that NPCRC’s mission is to create a new generation of scientific leaders to address workforce needs and close knowledge gaps in serious illness care through 2-year career development awards for early-stage investigators and pilot award funding for senior investigators. In addition, NPCRC has been providing technical assistance for investigators to better compete for federal funding to build the evidence base, create consensus around priorities for research across the lifespan, and establish and nourish a diverse national interdisciplinary community of serious illness scientists.

Morrison explained that with funding from NPCRC, Jean Kutner and Amy Abernethy organized a meeting to develop a strategy for creating a palliative care research cooperative (Abernethy et al., 2010). “This was important because not only did they develop this idea, but they also socialized it and sold it,” said Morrison. As a result, NINR decided in 2013 to fund the

Palliative Care Research Cooperative (PCRC), which has focused on clinical trials over the subsequent decade. PCRC’s strategy has been to provide technical assistance, training, and pilot awards for scientists at all levels of experience in conducting clinical studies. It has also been coordinating and resourcing nationally representative, multi-institutional studies that include diverse populations; providing a research infrastructure; and establishing a cooperative group-like structure to foster recruitment for clinical trials.

Noting NPCRC’s significant contributions to the field, Morrison explained that in 1997, only 18 institutions had a critical mass of three or more NIH R01-funded palliative care researchers. By 2022, that number was more than 70. Between 2006 and 2020, Morrison noted, over half of NIH serious illness research grants went to an NPCRC grantee or PCRC member, and nearly 60 percent of early-stage investigator awards went to NPCRC grantees.

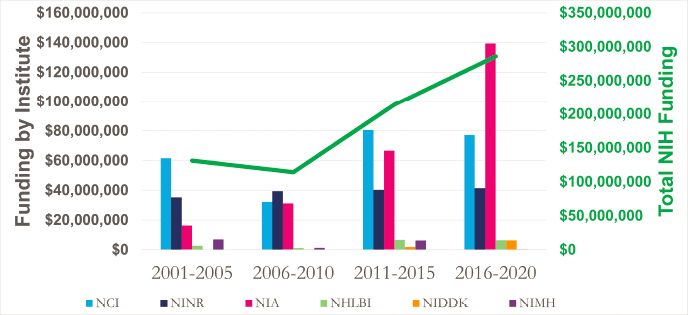

NIH funding for serious illness research increased from $60 million in 2001 to more than $304 million in 2022, Morrison noted, and NIA is now the largest funder (see Figure 5) (Brown et al., 2018; Buehler et al., 2022; Gelfman et al., 2013). “I think all of us in the field owe a huge debt of gratitude to the people at NIA for recognizing that serious illness needed a home, and they were supportive of that,” emphasized Morrison. From 2016 to 2020, NIA contributed approximately $140 million into research focused on older adults with serious illness.

NOTES: NCI = National Cancer Institute; NIH = National Institutes of Health; NINR = National Institute of Nursing Research; NIA = National Institute on Aging; NHLBI = National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; NIDDK = National Institute of Digestive, Diabetic, and Kidney Diseases; NIMH = National Institute of Mental Health.

SOURCES: Morrison presentation, November 2, 2023; Speaker created figure from data in Brown et al., 2018; Buehler et al., 2022; Gelfman et al., 2013.

In terms of the top-down strategy, Morrison said that NINR’s support has been critical, but NINR is a small institute with limited funds to support research. NIA was a good candidate to host more serious illness research, particularly since the National Alzheimer’s Project Act (NAPA)10 has provided millions of dollars to NIA to focus on Alzheimer’s disease. NAPA’s lack of a focus on people with advanced dementia prompted Morrison and his team to put together a list of evidence-based priorities to identify gaps in future directions in research for people with advanced dementia (Mitchell et al., 2012). With those priorities added to NAPA, NIA had a road map for supporting research on how to care for people with advanced dementia. To further inform NIA, Morrison explained, NPCRC partnered with NIA to convene a conference to establish research priorities in geriatric palliative care. The result was a series of papers published in the Journal of Palliative Medicine (Allcroft et al., 2013; Allen et al., 2013; Ersek et al., 2013; Hwang et al., 2013; Kelley, 2013; Kerr et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2013; McNamara et al., 2013; Morrison, 2013; Stanford et al., 2013; Xhixha et al., 2013), which sparked an NIA program focusing research on the needs of older adults with serious illness.

Morrison noted that a series of fortunate coincidences led CAPC and NPCRC to connect with Rebecca Kirch and colleagues of the American Cancer Society’s Cancer Action Network,11 through which they learned about the importance of advocacy. Morrison recounted that the American Cancer Society understood from its members that the needs of people living with advanced cancer were not being met and partnered with NPCRC and CAPC to insert language about enhancing research for people living with serious illness into Senate appropriations. Morrison explained that the Senate Labor Health and Human Services committee strongly urged in its fiscal year (FY) 2011 appropriations report that NIH should develop a trans-institute strategy for increasing funded research in palliative care for persons living with chronic and advanced illness.12

NPCRC, CAPC, and the American Cancer Society, along with the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, formed the Patient

___________________

10 For more information, see https://aspe.hhs.gov/collaborations-committees-advisory-groups/napa (accessed January 18, 2024).

11 For more information, see https://www.fightcancer.org/ (accessed January 19, 2024).

12 For more information, see https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3214714/ (accessed January 19, 2024).

Quality of Life Coalition (PQLC)13 in 2013, which included more than 40 advocacy organizations committed to improving care for people with serious illness. Morrison explained that the coalition serves as a unified voice to advocate on Capitol Hill for the needs of patients and their families. PQLC’s advocacy led to the Senate Labor Health and Human Services committee calling on NIH to increase support for palliative care research in its FY2019 appropriations report, noting that “research funding for palliative care, including pain and symptom management, comprises less than 0.1 percent of the NIH annual budget.” Morrison noted that the Senate committee strongly urged NIH to increase its support for palliative care research.

Morrison explained that after additional discussions with several Senate leaders in 2023, the FY2023 Congressional Consolidated Appropriations Act included the following language:14

Palliative Care. The agreement reiterates the need for NIH to develop and implement a trans institute strategy to expand and intensify national research programs in palliative care. The agreement urges NIH to ensure that palliative care is integrated into all areas of research across NIH and requests an update on plans to realize this coordination in the fiscal year 2024 Congressional Justification.

Morrison added that NIH provided the requested update, stating in part that it would lead efforts to convene subject matter experts from across the NIH institutes (including the National Cancer Institute, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institute of Mental Health, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, and NINR) to expand and strengthen the strategic coordination of palliative care research while working to identify future areas for research.

NIA issued a comprehensive response to Congress and claimed the lead role in convening subject matter experts from across the NIH institutes and centers to expand and intensify the strategic coordination of palliative care research efforts and identify future research topics. “What that meant was that there was now alignment at NIH for what [the field] wanted to do,” explained Morrison. The Appropriations Committee, with overwhelming bipartisan support, was then comfortable designating $12.5 million for NIA to implement a trans-institute, multi-disease strategy to focus, expand, and intensify national research programs in palliative care. In October 2023, NIA announced it would dedicate $66 million over 5 years to create a

___________________

13 For more information, see http://patientqualityoflife.org/ (accessed January 19, 2024).

14 See https://officeofbudget.od.nih.gov/pdfs/FY24/br/NIH%20FY%202024%20CJ%20Significant%20Items%20Volume%20final.pdf (pp. 94-96; accessed January 19, 2024).

consortium and trans-institute strategy to promote palliative care research.15 Morrison emphasized that although NIA has been designated as the lead institute, the focus is on serious illness care research across the lifespan.

Morrison closed his remarks with a quote from Sir Winston Churchill: “Now, this is not the end. It is not even the beginning to the end. But it is, perhaps, the end of the beginning.” Morrison shared that it is his hope that the workshop’s discussions would set the stage for the next phase of serious illness research in this country.

Audience Q&A

Session moderator Aslakson opened the Q&A session by asking Morrison what is next for the field of serious illness care given the potential for increased NIH funding. Morrison responded that some general principles are that research should include the entire lifespan, include multiple diseases—investigators will have to leave their silos—and be interdisciplinary in its approach to accounting for the factors—such as who pays for care—that can influence and improve care. As funding for palliative care research is still only about 1 percent of the NIH budget, it will be important to be strategic over the next 5 years regarding how the field can most effectively leverage the resources it has spent 20 years trying to secure. “We have to have a shared agenda,” Morrison emphasized. “We have to come together the way we did in terms of planning the field.” In Morrison’s view, the available funds need to go to scientific research that will make a difference tomorrow, not in 20 years.

Erik Fromme, faculty member in Ariadne Labs’ serious illness care program, asked Morrison to elaborate on his point about researchers getting out of their silos. Morrison replied that NIA wants a transdisciplinary and trans-institute approach, and although NIH has struggled with how to promote such efforts, he believes things might be different for palliative care. First, funding is allocated to this effort, and second, it has leadership. “There is a group of people at both the top and mid-levels of NIH who are committed

___________________

15 For more information, see https://www.nia.nih.gov/about/budget/fiscal-year-2024-budget (accessed January 19, 2024). See also https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-AG-23-050.html (accessed January 19, 2024). In March 2024, Congress passed an FY2024 appropriations package that will provide $12.5 million in funding for NIA to implement a trans-institute, multi-disease strategy to focus, expand, and intensify national research programs in palliative care across the lifespan. See https://www.appropriations.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/fy24_lhhs_bill_summary.pdf (accessed May 9, 2024).

to this, both at a personal and professional level, and we have not seen that before,” said Morrison. He noted that he is not naive enough to expect every silo to disappear but is optimistic because the proposed consortium includes the large NIH institutes, including the National Cancer Institute.16

Rebecca Kirch, executive vice president of policy and programs at the National Patient Advocate Foundation,17 said that one of the many things palliative care has done well has been its engagement with patients and families. The next step, she said, is to integrate the voices of those who are underrepresented. Her organization’s infrastructure is designed to help link researchers to underrepresented, lower-income, and rural populations and people of color who do not trust the system or clinical trials. The opportunity, she said, is to bring patients from those populations into advisory groups as experts and not as tokens.

IMPROVING EVIDENCE GENERATION TO ADDRESS GAPS IN SERIOUS ILLNESS CARE RESEARCH: RESEARCH METHODOLOGY/STUDY DESIGN

Dio Kavalieratos, associate professor and director of research and quality in the Division of Palliative Medicine at Emory University’s Rollins School of Public Health, reflected on the growth and progress of scientific inquiry and increased rigor in serious illness research over the past two decades. He cited a 2008 systematic review of clinical trials for specialized palliative care intervention that found scant evidence that it was effective (Zimmermann et al., 2008) and noted that the evidence base was hampered by methodological limitations. Twelve years later, however, another systematic review found multiplicative growth in the number of studies of specialized palliative care (Ernecoff et al., 2020) and highlighted the diversification of the breadth and depth of the methods used in serious illness care research. “Those of us in serious illness research know all too well that the populations, the settings, and the context within which we work make our research different,” noted Kavalieratos. “Standard methodologies, like a traditional randomized clinical trial, often do not perform as well when they are taken off the shelf and applied in serious illness contexts.” Rather, he said, such trials require remarkable scientific expertise and agility to understand when and how to adapt those methods to fit the purpose of the study and the reality of the population being studied.

___________________

16 An updated overview is available at https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/rfa-files/RFA-AG-25-002.html (accessed March 22, 2024).

17 For more information, see https://www.npaf.org/resources/patient-insight-institute-2/ (accessed January 5, 2024).

Mixed Methods Research and Evaluating Complex Interventions

Douglas White, vice chair and professor of critical care medicine, and director of the Program on Ethics and Decision Making in Critical Illness at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, characterized qualitative and mixed methods research as “crucial tools to improve serious illness care.” He defined qualitative research as “a type of research that aims to gather and analyze non-numerical data in order to gain an understanding of individuals’ social reality, including understanding their attitudes, beliefs, and motivations” (Tashakkori and Teddlie, 2010). Mixed methods research, White said, “includes both qualitative and quantitative data collection and analysis in parallel form or in sequential form, in which one type of data provides a basis for collecting another type of data” (Tashakkori and Teddlie, 2010). An example of the latter, he explained, would be doing qualitative research and developing a quantitative survey based on those results.

The purposes of quantitative and qualitative research are quite different, explained White. Quantitative research aims to establish incidence and prevalence, measure risks and frequency of events, and determine treatment efficacy in rigorous trials. The goal of qualitative research, on the other hand, is to describe a phenomenon with rich texture, understand attitudes and behaviors in a deeper way than can be obtained from a quantitative survey, and describe why interventions tested in large clinical trials do or do not work. Both methods are part of the crucial work needed at the formative stage of research if the goal is to improve serious illness care, as White noted: “We need to understand the nature of the problem or problems if we are to intervene successfully to address them.” He added that it is also important to understand where dominant paradigms and extant policies do not fit either method because of insufficient consideration of diverse views or insufficient inclusion of groups that have historically been marginalized.

White gave two examples of qualitative research studies in serious illness care to illustrate those points. In one study, investigators conducted focused ethnography to understand Navajo perspectives regarding disclosing negative information and talking about negative health status in the future (Carrese and Rhodes, 1995). This study found that the dominant Western paradigm of needing to talk about what an individual wants in the context of becoming seriously ill is in tension with cultural views in the Navajo community around not talking about negative future events. “That was an important study drawing out concerns about whether our

Western bioethical perspective fully fits with the cultures that we serve,” said White.

The second study characterized key intrapersonal tensions experienced by surrogate decision makers in ICUs and explored associated coping strategies (Schenker et al., 2012). In this case, the problems are not solely informational, as deep existential and psychological challenges arise in making end-of-life decisions for loved ones.

White shared an example of a mixed methods study he and his collaborators conducted, in which quantitative data suggested that surrogate decision makers for critical illness often have overly optimistic expectations about their loved one’s prognosis; the team wanted to understand why this might be so (White et al., 2016). The assumption most people make is that decision makers are misunderstanding the information they receive from clinicians. To investigate, White’s team interviewed surrogate decision makers and physicians during patients’ stays in the ICU and asked them what they believed the chances of survival were. The researchers found that 43 percent of surrogates held overly optimistic expectations compared to the physician. This was more common for Black or strongly religious surrogates. White’s team also asked the surrogates about the doctor’s perspective on survival. The answers revealed that optimistic expectations arose from both miscomprehension and differences in belief.

As a follow-up, the team interviewed the surrogates who did not believe the physicians and asked them to explain why that was the case (White et al., 2019). White explained that the qualitative portion of the project provided information that was illuminating and had significant implications for the design of future interventions. In general, the answers fell in three categories: a belief that they know the patient’s fortitude better than the physician, optimism grounded in religious beliefs, and defensive processing of prognosis. “I would just point out that each of these reasons is not really amenable to a decision aid or an information-focused intervention, and this tells us that we need to go looking in different places for the kind of interventions that may work,” explained White.

White cited two papers on reporting and designing qualitative research (O’Brien et al., 2014; Tong et al., 2007) and pointed out that when evaluating complex interventions to improve serious illness care, rigorous strategies are needed to monitor and maintain fidelity. An intervention might be complex because of its own properties, such as the number of components; range of behaviors targeted; or expertise and skills required (Skivington et al., 2021). Although many factors can make an intervention complex, the important point, said White, is that almost everything in serious illness

care involves complex interventions. “We have not quite conceptualized it in that way, to our detriment,” observed White.

White emphasized that it is critical to monitor and maintain intervention fidelity—the degree to which it is delivered as planned—“because that affects how to interpret both positive and negative trials.” For example, if a trial result is negative, it is important to know whether the intervention was delivered per protocol or did not work despite sufficiently high fidelity. The latter provides useful evidence to guide interventions. White highlighted three keys to fidelity:

- specify the core components of the intervention when designing it,

- train the interventionists and ensure they demonstrate proficiency to deliver it, and

- measure the extent to which it is being delivered (Bellg et al., 2004; Resnick et al., 2005).

Also important, said White, is studying the extent to which participants enacted the intervention and acquired the necessary treatment-related behavioral skills or cognitive strategies.