Tackling the Road Safety Crisis: Saving Lives Through Research and Action (2024)

Chapter: 1 Introduction

1

Introduction

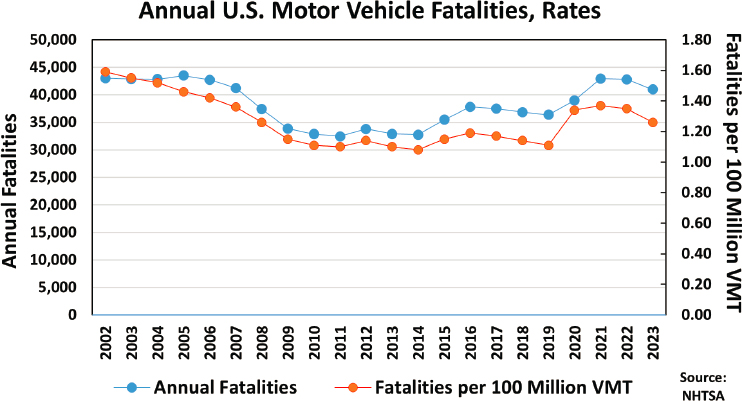

Despite significant investments in motor vehicle safety research, traffic deaths and serious injuries in the United States have been climbing for the past decade (see Figure 1-1). From a low of 32,744 in 2014, deaths on the roads reached 42,785 in 2022,1 and the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) estimates that there were 40,990 traffic deaths in 2023.2 In addition to the immense personal tragedy, these deaths pose a substantial economic loss to U.S. society. The National Safety Council’s estimate of the societal costs of traffic fatalities in 2021, which includes the monetary value of the lives lost and other direct costs such as property damage, medical care, and first responders, totals $498 billion.3,4 During

___________________

1 NHTSA. “2020 Fatality Data Show Increased Traffic Fatalities During Pandemic.” Text. Accessed May 1, 2024. https://www.nhtsa.gov/press-releases/2020-fatality-data-show-increased-traffic-fatalities-during-pandemic.

2 National Center for Statistics and Analysis. 2024, April. Early Estimate of Motor Vehicle Traffic Fatalities in 2023. Crash Stats Brief Statistical Summary. Report no. DOT HS 813 561. NHTSA.

3 NHTSA’s estimate is 42,915 roadway fatalities in 2021. NHTSA’s 2021 Estimate of Traffic Deaths Shows 16-Year High. FHWA estimates that the 2021 statistical value of a life is $11.8 million, which represents the estimated economic costs of crashes of all types. “Departmental Guidance on Valuation of a Statistical Life in Economic Analysis | US Department of Transportation.” n.d. Accessed June 21, 2024. https://www.transportation.gov/office-policy/transportation-policy/revised-departmental-guidance-on-valuation-of-a-statistical-life-in-economic-analysis. NHTSA and NSC use slightly different methodology; for a full explanation, see https://injuryfacts.nsc.org/motor-vehicle/overview/comparison-of-nsc-and-nhtsa-estimates.

4 See also “NSC Injury Facts.” https://injuryfacts.nsc.org/all-injuries/costs/guide-to-calculating-costs/data-details.

SOURCE: NHTSA.

this same period, other high-income nations have successfully reduced their traffic fatality rates to levels much lower than the United States.5

Despite decades of an extensive array of road safety research, repeated leadership commitments to making safety a priority, and substantial changes in safety designs and technologies for the vehicle fleet, U.S. road safety has not improved substantially. Why has the United States not done better? This question has been the subject of prior studies by the Transportation Research Board (TRB) and others and is the critical context for this study of transitioning evidence-based research into practice.

STUDY SCOPE AND PROCESS

To assess the effectiveness of road safety research and its implementation, the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO), and the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (IIHS) asked TRB to assemble an expert committee to study the process for transitioning evidence-based road safety research into practice and to recommend improvements. Road safety is a product of the road, the vehicle, and user behavior but as we describe in Chapter 3, it is also a product of the processes we use to identify and

___________________

5 Transportation Research Board. 2010. TRB Special Report 300: Achieving Traffic Safety Goals in the United States: Lessons from Other Nations. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/13046.

deploy protective interventions.6 While this study focuses on road design and operation, it acknowledges the interaction of road design and user behavior and includes vehicle design where relevant. The full Statement of Task is in Box 1-1.

The committee was made up of 12 experts in various aspects of road safety, representing state and municipal departments of transportation, safety research, medicine, and the motor vehicle industry. Its work comprised six components:

- Discussion and interpretation of the Statement of Task to provide clear guidance for its work and to bound the study.

- Literature research, supported by TRB library resources and enhanced by the work of all members of the committee.

- Monthly, half-day virtual committee meetings, interspersed with five 1.5 day in-person meetings.

- Between committee meetings, members collaborated in smaller groups and several subcommittees were created to accomplish specific tasks.

- Public presentations to the committee, from many experts in the field, consistent with the Federal Advisory Committee Act.

The committee’s process was cyclical, moving among these activities and circling back where new questions arose and new evidence was discovered.

To interpret the statement of task, the committee discussed the broader road safety problem, considering in particular the worsening trends in U.S. road safety in comparison to increases in safety in peer countries in Europe, North America, and South Asia. Because the methods used by these peer countries and others to improve road safety are well documented and widely available in the research literature, the committee did not view gaps in general research findings as the primary obstacle to transitioning research into road safety practice and outcomes. As a consequence, the committee went beyond the production of road safety research to examine the entire process addressing road safety problems. This process consists of research project selection and funding as well as the conduct of research, the development and dissemination of guidance for practitioners, and the incorporation of feedback from the field to inform future research. It also includes the timeliness, relevance, clarity, and consistency of guidance for and education and training of practitioners. This focus led the committee to an exploration of the challenges to transitioning evidence-based research on road safety into practice (see Box 1-2).

___________________

6 According to the epidemiologic triad and public health principles, this is the product of the person (host), vehicle and roadway (environment), and kinetic energy (agent).

BOX 1-1

Project Statement of Task

A National Academies consensus study committee will examine the influence of safety research on the practice of road safety and the tools and resources used by practitioners. In particular, consideration will be given to how objective, evidence-based road safety research is produced and disseminated in a timely and consistent manner to inform the planning, design, and operations of road infrastructure. In doing so, the following questions will be considered along with others deemed appropriate by the committee:

- How are objective and evidence-based research findings produced?

- What can be done to streamline and hasten the process of ensuring that high-quality and objective safety research that has been conducted makes its way into standards development and guidance documents?

- How is the research validated and by whom?

- What are the main guides, tools, coursework, and other resources that transportation planners, highway designers, traffic engineers, and other highway professionals consult when making design and engineering choices that affect the safety performance of the road and traffic environment?

- To what extent are these practitioner resources informed and influenced by the results of evidence-based research and what mechanisms are in place to ensure that the results are incorporated in a timely, accurate, transparent, and systematic manner into these practitioner resources, while also ensuring that deficient research results are not used?

- Who are the key actors that can bring about any needed change in practice, and what are the processes for doing so?

- In cases where there are gaps in the availability of evidence-based research, are there effective mechanisms for ensuring that these gaps are filled by sponsoring the needed research?

- How can the dialogue between the research community and the practitioner community be improved to ensure that immediate safety research needs are met while also ensuring more strategic research is undertaken that elevates the state of the practice as a whole?

After assessing the research-to-practice process for road safety, the committee will explore equivalent processes from other fields and disciplines such as medicine, public health, and education, as well as other engineering-oriented fields such as commercial and residential building design and construction. Although not the primary focus of the study, the committee may want to examine the processes in place to ensure that evidence-based research is programmed and conducted to produce reliable and useable results for practitioners—for instance, by considering any significant changes to the research prioritization process in recent years. The committee will consider ways to improve the dialogue and engagement between the research and practitioner communities for achieving early progress in transitioning research results to practice. It will also consider ways to make longer-term and sustained improvements to the road safety research-to-practice process. Based on these assessments and the professional judgment of its members, the committee will recommend actions and strategies to improve the road safety research-to-practice process.

BOX 1-2

Definition: Evidence-Based Road Safety Research

Evidence-based road safety research is the study of the effect on crash frequency and severity of infrastructure, behavioral, other crash interventions, or roadway characteristics using observational studies conducted on public roads. It compares crash outcomes without and with the interventions or characteristics, includes multiple field studies, and is published in recognized journals to assure peer review of experimental designs and analysis methods.

The committee then proceeded to identify ways to overcome those challenges. After documenting and assessing the research-to-practice process for road safety, the committee explored the science of research translation in other fields, specifically biomedicine, early childhood education, and motor vehicle safety technology. The committee also conducted a review of road safety research prioritization processes and recommendations since 1990 and evaluated ways to make longer-term and sustained improvements to the road safety research-to-practice process.

REVIEW OF PREVIOUS STUDIES

The committee’s work built on previous studies that sought to prioritize road safety research and ensure that the research produced reliable and useful findings that could be translated and widely adopted into practice.7 While road safety research dates back to the dawn of the automobile, the modern era of federal funding and regulation dates to the 1966 passage of the Motor Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act, which assigned to the federal government responsibility to set Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards (FMVSS),8 and its companion the Highway Safety Act, which, among its provisions, funded state efforts to address road safety and mandated the creation of the Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD). The Highway Safety Act also provided funding for federal, state and local highway safety research programs.9 The National Cooperative

___________________

7 Committee on Research Priorities and Coordination in Highway Infrastructure and Operations Safety. (2008). TRB Special Report 292: Safety Research on Highway Infrastructure and Operations: Improving Priorities, Coordination, and Quality. Transportation Research Board of the National Academies, Washington, DC.

8 Public Law 89-563, Sept 9, 1966, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-80/pdf/STATUTE-80-Pg718.pdf#page=1.

9 Public Law 89-564, Sept. 9, 1966, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-80/pdf/STATUTE-80-Pg731.pdf#page=5.

Highway Research Program (NCHRP), founded in 1962 and managed by then Highway Research Board and charged with providing practical, ready-to-implement solutions to pressing problems faced by state departments of transportation, also addresses road safety.10 Table 1-1 provides a summary of major road safety milestones and TRB studies related to road safety or strategic approaches to research.

In the 1980s TRB convened committees of experts that produced recommendations on the 55-mph speed limit and seatbelts and other child safety restraints.11 The decade also saw the emergence of TRB consensus studies advocating for a more strategic and coordinated approach to transportation research. Beginning with America’s Highways: Accelerating the Search for Innovation (TRB Special Report 202, 1984), these reports also examined transportation research needs and the research-to-practice process.12

Safety Research for a Changing Highway Environment (TRB Special Report 229, 1990) addressed specific weaknesses in U.S. road safety research, including the scale (funding) and scope, the scientific quality, as well as the failure to build the capacity to sustain a meaningful safety research effort. The report found that government-funded road safety research had declined in the 1980s, and that the limited amount of funding available was not being utilized effectively due to siloed and narrow program goals among disparate organizations. Additionally, the report identified a lack of political support for investing in the next generation of road safety researchers, creating a risk of insufficient evidence-based studies to assess future safety issues. Among its recommendations were the “joint planning of long-term highway safety research agendas;” the creation of “multiyear research plans with input from other appropriate federal agencies, the states, and private industry;” and the founding of a “new cooperative program for state-sponsored highway safety research.”13

In 2001, another TRB consensus study, Strategic Highway Research: Saving Lives, Reducing Congestion, Improving Quality of Life (TRB Special Report 260, 2001), outlined a national program of targeted highway

___________________

10 NCHRP. “NCHRP Overview.” Accessed March 13, 2024. https://www.trb.org/NCHRP/NCHRPOverview.aspx.

11 National Research Council. 1989. Safety Belts, Airbags, and Child Restraints: Special Report 224. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/11350; National Research Council. 1984. 55: A Decade of Experience: Special Report 204. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/11373.

12 National Research Council. 1984. America’s Highways: Accelerating the Search for Innovation: Special Report 202. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/11374.

13 National Research Council. 1990. Safety Research for a Changing Highway Environment: Special Report 229. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/11411. P. 126.

TABLE 1-1 Major Road Safety Milestones and TRB Safety Studies

| Year | Milestone or Report | Safety Impacts |

|---|---|---|

| 1966 | Accidental Death and Disability: The Neglected Disease of Modern Society (National Academy of Sciences) | Quantified the substantial impact of disabilities on society, including those caused by motor vehicle accidents. |

| 1966 | Highway Safety Act and Motor Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act | First national requirements for motor vehicle and road design safety standards. |

| 1968 | Title 49 of the United States Code, Chapter 301, Motor Vehicle Safety | Seatbelts required in all new cars. |

| 1971 | Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standard 213 | First children’s car seat protection standards. |

| 1973 | Highway Safety Act of 1973 | Required post-crash investigations and created the first institutionalized safety management processes. |

| 1984 | 55: A Decade of Experience (TRB Special Report 204) | Highlighted the safety benefits of the 55-mph national speed limit and called for its continuation (although it would be repealed in 1995). |

| 1984 | New York Seat Belt Law | New York becomes first state to mandate usage of seatbelts. |

| 1984 | America’s Highways: Accelerating the Search for Innovation (TRB Special Report 202) | Critiqued the current state of highway research and called for creating a new strategic program to manage/coordinate efforts in key gap areas. |

| 1989 | Safety Belts, Airbags, and Child Restraints (TRB Special Report 224) | Called for public behavioral messaging campaigns to increase seatbelt usage; recognized that law enforcement is not sufficient to improve road safety outcomes. |

| 1990 | Safety Research for a Changing Highway Environment (TRB Special Report 229) | Called for a more coordinated and cooperative approach to developing road safety research agendas. |

| 1991 | Disability in America (Institute of Medicine) | Argued that most disabilities, including those caused by motor vehicle accidents, are preventable. |

| 2001 | Strategic Highway Research: Saving Lives, Reducing Congestion, Improving Quality of Life (TRB Special Report 260) | Outlined a targeted national highway research program that included improving safety, which was funded by Congress in 2005. |

| Year | Milestone or Report | Safety Impacts |

|---|---|---|

| 2005 | Safe, Accountable, Flexible, Efficient Transportation Equity Act: A Legacy for Users (SAFETEA-LU) | Created the core Highway Safety Improvement Program, which requires states to develop strategic highway safety plans, and increased funding for safety improvements. |

| 2008 | Safety Research on Highway Infrastructure and Operations: Improving Priorities, Coordination, and Quality (TRB Special Report 292) | Recommended the creation of an independent scientific advisory committee charged with recommending a national safety research agenda. |

| 2022 | National Roadway Safety Strategy (NRSS) | Outlined the U.S. Department of Transportation’s approach to reducing serious injuries and deaths, which included safer drivers and driving habits, engineering safer roads, developing safer vehicles, speed management, and improved post-crash care. Outputs of this strategy include the Safe System Approach, the Safe Streets and Roads for All (SS4A) Grant program and a Complete Streets initiative. |

| 2024 | Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standard #127 | Requires all new cars to be equipped with automatic braking and crash avoidance systems by 2029, potentially preventing ~360 fatalities and ~24,000 injuries annually. |

SOURCE: Milestones from “Road Safety Fundamentals Unit 1: Foundations of Road Safety.” Accessed July 10, 2024. https://highways.dot.gov/safety/learn-safety/road-safety-fundamentals-html-version/unit-1-foundations-road-safety.

research. This study identified two critical safety knowledge gaps: (1) inadequate precision in the understanding of how various factors contribute to crashes and (2) information on the cost-effectiveness of countermeasures already in use or under consideration.14 This study ultimately led to federal funding for the Strategic Highway Research Program 2 (SHRP 2), and a body of research intended to significantly improve highway safety was one of SHRP 2’s four program components.15

___________________

14 Transportation Research Board. 2001. Strategic Highway Research: Saving Lives, Reducing Congestion, Improving Quality of Life: Special Report 260. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/10223.

15 TRB. “The Second Strategic Highway Research Program (2006–2015).” Accessed April 24, 2024. https://www.trb.org/StrategicHighwayResearchProgram2SHRP2/Blank2.aspx.

In 2005, TRB was again asked to convene an expert committee to conduct an independent review of road safety research priorities.16 The final report, Safety Research on Highway Infrastructure and Operations (TRB Special Report 292, 2008), called out the absence of a data-driven safety research agenda and recommended the establishment of an independent committee charged with recommending a national research agenda:

The committee recommends that an independent scientific Advisory committee (SAC), consisting primarily of experienced safety program managers and knowledgeable researchers, be charged with (a) developing a transparent process for identifying and prioritizing research needs and opportunities in highway safety, with emphasis on infrastructure and operations; and (b) using the process to recommend a national research agenda that focuses on highway infrastructure and operations safety.17

This committee was not established, and the need for an informed and transparent process for producing a national road safety research agenda remains unmet.

REPORT OUTLINE

The current chapter, Chapter 1, covers the study origins and Statement of Task and explains how the committee interpreted the Statement of Task. Chapter 2 describes the road safety crisis in the United States, provides an overview of the challenge of moving safety research from the perspective of practitioners, and introduces political and cultural factors unique to the United States that can make it difficult to put the best, proven crash countermeasures (see Box 1-3) into practice. This chapter contrasts U.S. practice with approaches used with success in other nations, and it ends with an outline of the federal policy responses to road safety problems.

Chapter 3 describes the current U.S. process of translating safety research through the use of a logic model with phases: (1) road safety research, (2) crash countermeasure implementation, and (3) before-after evaluation. Chapter 4 takes a deep dive into the challenges that can interrupt the flow of evidence-based research into the field. The chapter describes the standards and guidance used for road projects and examines the countermeasure deployment process in detail for planning and implementing

___________________

16 AASHTO. “Strategic Highway Safety Plan,” 2005. https://store.transportation.org/Common/DownloadContentFiles?id=701.

17 Committee on Research Priorities and Coordination in Highway Infrastructure and Operations Safety. 2008. TRB Special Report 292: Safety Research on Highway Infrastructure and Operations: Improving Priorities, Coordination, and Quality. Transportation Research Board of the National Academies, Washington, DC.

BOX 1-3

What Is a Safety “Countermeasure”?

The term “countermeasure” appears throughout this report in the context of techniques or methods to achieve safety for roads, motor vehicles, and user behavior. The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) defines “countermeasure” to mean “an action taken to counteract a danger or threat. In the context of safety—a safety countermeasure is an action designed to counteract a threat to safety.” FHWA also identifies terms related to “countermeasure” such as “treatment, ‘fix,’ improvement, or mitigation.”

FHWA provides the following example of how countermeasures are used for road safety: “After examining traffic crash history, roadway geometry, and other factors, the construction of a modern roundabout was selected as the appropriate countermeasure to address identified safety issues.” As can be seen in this example and in the related terms, the threat–countermeasure approach to safety presumes that the baseline situation—the road design or user behavior, for example—has created a problem that the countermeasure is to fix. Therefore, in general, the threat–countermeasure approach to safety is reactive.

SOURCE: FHWA. “Improving Safety of Rural, Local, and Tribal Roads.” Last updated October 4, 2013. https://safety.fhwa.dot.gov/local_rural/training/fhwasa14072/sec7.cfm.

road safety countermeasures and countermeasure research. Chapter 5 reviews the general process of research translation, focusing on the medical field, where it is highly developed, and compares this to what is done in road safety, in search of strategies that might ensure that the most useful evidence-based research results will reach the users, both practitioners and road users themselves. Two other examples of research translation are examined for comparison: policy research on early childhood education and safety research in the motor vehicle industry. Chapter 6 summarizes the committee’s analysis and then provides its recommendations. Throughout the report, selected sidebars describe examples and case studies for context.