Tackling the Road Safety Crisis: Saving Lives Through Research and Action (2024)

Chapter: 4 Challenges to Moving Crash Countermeasures into Practice

4

Challenges to Moving Crash Countermeasures into Practice

This chapter describes some of the challenges and complexities involved in moving the findings and products of road safety research into practice. In the United States, the road safety research-to-practice process takes place in the context of federalism: the federal government does not simply dictate road standards, but instead encourages safety by aligning road safety planning, countermeasure analysis procedures, and design guidance with the requirements of federal funding programs. In a few cases, the federal government has created baseline rules or used financial benefits to incentive policy change at the state level, such as setting blood alcohol limits to 0.08%.1 However, to a large extent, the federal government has been reluctant to mandate a one-size-fits-all approach to road safety. As a result, flexibility and engineering judgment play a significant role in the implementation of crash countermeasures at the state and local levels. Still, much federal guidance in highway design and operations is seen as de facto standards, and deviation can be difficult and calls for justification.

The chapter begins with a description of the key sources of standards and guidance that underpin the design and operation of roads in the United States. These include the Federal Highway Administration’s (FHWA’s) Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices and the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials’ (AASHTO’s) A Policy on

___________________

1 Alcohol Policy Information System. “About This Policy: Blood Alcohol Concentration (BAC) Limits: Adult Operators of Noncommercial Motor Vehicles.” Accessed July 2024. https://alcohol-policy.niaaa.nih.gov/apis-policy-topics/adult-operators-of-noncommercial-motor-vehicles/12/about-this-policy#page-content.

Geometric Design of Highways and Streets, as well as specialized guides for urban streets and pedestrian and bicycle facilities. Safety is at least implicit in these standards, manuals, and guides, but these publications also (and for some guidance, primarily) address other project purposes, such as congestion relief, energy conservation, or truck accessibility. The chapter then covers the process used to create a road safety project that deploys crash countermeasures. The process is presented in the context of the federal Highway Safety Improvement Program (HSIP), which funds road safety projects implemented by states and local jurisdictions. Major project development guidance sources covered include AASHTO’s Highway Safety Manual and the Crash Modification Factor Clearinghouse. A sidebar on the Complete Streets Program examines the need for both typical road design manuals and the road safety project process to adapt to accommodate new approaches to road safety and the needs of a broader set of road users. The chapter then briefly compares the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration’s (NHTSA’s) safety planning and tools for behavioral safety interventions with FHWA’s processes and resources for road infrastructure crash countermeasures.

Because implementing road safety practices requires complicated analyses and significant amounts of engineering knowledge and judgment, the education of road safety professionals is paramount. The chapter closes with an examination of the lack of road safety education in the typical civil engineering curriculum, the reliance of the road safety field on professional education and the importance of engineering judgment.

STANDARDS AND GUIDANCE FOR DESIGNING ROADS

Every road project has one or more purposes, which should be reflected in its planning and design. While safety is always important, it may not be the primary objective of the project. For some road projects, the primary purpose may be, for example, to reduce congestion, increase transit reliability, or improve air quality. However, the committee observes that whenever an agency intervenes to make an improvement in a road section, there may be opportunities to improve its safety—any project might also be a safety project. This section examines the standards and guidance used for road projects where safety is a condition, not a goal or where safety is co-equal with other goals. The entry point for improving safety is finding the right, most important, most opportune places to address safety. This is usually accomplished by conducting a data-driven network screening technique based on criteria such as crash locations, fatal crash counts, crash rates, crash severity, public complaints, or other criteria. This can be done with systematic tools or nominal methods.

The section begins with a discussion of different strategies for selecting crash countermeasures. It then reviews key sources of road design guidance, most notably FHWA’s Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD) and AASHTO’s A Policy on Geometric Design of Highways and Streets (commonly known as the “Green Book”). Until relatively recently, these two publications in their numerous editions have been responsible for the design of most of the roadways that motorists, pedestrians, bicyclists, and transit users experience on a daily basis. The chapter then discusses other design guides, including the alternate design guides recognized by FHWA. These latter design guides often emphasize road design for people walking, rolling, biking, or taking transit or for contexts where facilitating the movement of motor vehicles is not the primary goal.

A common theme in highway engineering is a desire for “flexibility” that requires the extensive use of engineering judgment. In many cases, these standards, manuals, and guides do not direct engineers but rather define the universe of acceptable options from which engineers choose. Indeed, the first step—either taken by policymakers or road designers—is often to pick the source of guidance.

The publications and guides described here may also be sources of crash countermeasures, as discussed in the following section, although this is not their primary purpose. The main sources of roadway design guidance are the result of collaborative efforts involving committees of experts, each with its own quality control process.

The challenge for practitioners—a barrier to the flow of evidence-based safety research onto the road network—is the task of working through the several sources and layers of guidance provided. As discussed below, these sources are overlapping, they can be in conflict, and it is left to the safety practitioner to sort out and select the sources to use, relying on their knowledge and judgment or, in some cases following an agency mandate that may not be suitable for the situation. Crash countermeasures can be chosen using two different methods. Historically, the approach has been to invest in problematic locations to bring them up to established design standards; for example, as presented in the AASHTO Greenbook, the MUTCD or similar source. This is sometimes described as the nominal approach to safety.

Importantly, this approach does not consider the expected effect on crash experience as a result of the design change: the roadway is considered “safe” if it meets the minimum design standards. Meeting or exceeding minimum standards has been assumed to improve safety, but in some circumstances, such actions can lead to higher speeds and thus greater crash risk.2 This is evidenced by the nearly 40,000 deaths that still occur

___________________

2 Donnell, E.T., S.C. Hines, K.M. Mahoney, R.J. Porter, and H. McGee. 2009. Speed Concepts: Informational Guide. FHWA-SA-10-001.

on roads in the United States every year,3 despite most of the roads meeting standards. More concerning is that some accepted design standards are not research-based, but rather legacy standards.4 In such cases, adopting nominal design standards may be unproductive or even counterproductive.

The other method is to use a substantive approach, which guides the search for crash countermeasures using situation-specific analyses as directed by the HSM. This requires local traffic and contextual data and predictions of safety outcomes using calibrated safety performance functions (SPFs) to predict the future in the absence of intervention. This presents a more informed picture of current and future safety performance and thus provides a stronger basis for predicting and measuring the benefits of a particular countermeasure.

Challenges to using substantive safety analysis include more extensive data requirements—not just difficult but in some cases impossible to meet—and the effort and skills required by practitioners. Here, training and more supportive data and analysis tools can contribute to improving crash countermeasure selection.

Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices

The MUTCD establishes national standards for all traffic control devices (e.g., signs, signals, and pavement markings) and their design, application, and placement. It is an American National Standards Institute (ANSI) standard that must be adopted through the Federal Register rulemaking process, requiring broad and extensive review for changes, and thus it is slow to change. The MUTCD covers all streets, highways, pedestrian and bicycle facilities, and roadways on and private facilities open to public travel. Originating in 1938, FHWA has administered it since 1971. The MUTCD is promulgated as a federal regulation, and amendments to the MUTCD must also go through the federal rulemaking process. The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act/Bipartisan Infrastructure Law required FHWA to amend the existing regulation to “promote the safety, inclusion, and mobility of all users,” within 18 months and to review and amend it at least every 4 years.5 For public agencies, noncompliance can result in the

___________________

3 U.S. Department of Transportation. 2020, January. National Roadway Safety Strategy.

4 Hauer, E. 2016. “An Exemplum and Its Road Safety Morals.” Accident Analysis & Prevention 94:168–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2016.05.024.

5 U.S. Congress. 2021. “Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act.”

loss of federal funding. Failure to follow the standards in the MUTCD can also lead to exposure to tort liability.6

The MUTCD contains information in the form of “standard, guidance, options, and support.” States may adopt their own MUTCDs or MUTCD supplements, but each state-level document must include the minimum standards found in the national MUTCD “unless the reason for not including it is satisfactorily explained based on engineering judgment, specific conflicting State law, or a documented engineering study.” However, applying the MUTCD still relies on engineering judgment. It explicitly states that “the decision to use a particular device at a particular location should be made on the basis of either an engineering study or the application of engineering judgment … this manual should not be considered a substitute for engineering judgment.”7 The MUTCD sometimes advises that engineering judgment be used to determine how certain traffic control devices are selected. In these cases, the HSM can serve to supplement that judgment with safety performance insights.8

AASHTO’s “Green Book” and the National Highway System

AASHTO’s A Policy on Geometric Design of Highways and Streets9 (the “Green Book”) contains the “current design research and practices for highway and street geometric design.”10 This policy covers design elements such as number of lanes, lane widths, curves, slopes, and intersections. First published in 1984, the Green Book organizes its design guidance around a road’s functional classification (principal arterial, minor arterial, collector, and local road/street systems) and urban or rural context. It includes pedestrian, bicycle, and transit facilities, although most of its content addresses the capabilities, needs, and safety of motor vehicles. Typically, a state, regional, or municipal transportation plan would designate the type of road—a low-speed urban collector street, for example—and the Green Book would be consulted for guidance on how it should be designed. The Green Book provides guidance, not official standards, and explicitly states

___________________

6 FHWA. “Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD): Overview.” Last modified November 16, 2023. https://mutcd.fhwa.dot.gov/kno-overview.htm; FHWA. “Frequently Asked Questions – General Questions on the MUTCD.” Last modified November 22, 2023. https://mutcd.fhwa.dot.gov/knowledge/faqs/faq_general.htm#state.

7 FHWA. 2023. “Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices for Streets and Highways,” 11th ed. Section 1D.03.

8 AASHTO HSM website. https://www.highway-safetymanual.org/Pages/support_answers.aspx.

9 AASHTO. 2018. Policy on Geometric Design of Highways and Streets, 7th ed.

10 Weingroff, R.F. 2014, September/October. “Celebrating a Century of Cooperation.” Public Roads, https://highways.dot.gov/public-roads/septemberoctober-2014/celebrating-century-cooperation.

that it “is not intended to be a prescriptive design manual that supersedes engineering judgment by the knowledgeable design professional.”11

AASHTO’s Green Book does not require that decision-makers prioritize safety over other transportation goals, such as minimizing travel time. If the chosen project goal is to minimize travel time or maintain free-flowing traffic for motor vehicles, the Green Book provides detailed design guidance on how to achieve these goals. Indeed, its guidance on selecting the desired level of service—a measure of the freedom of flow of motor vehicle traffic12—for a road recommends striving to provide the best level of service practical “as may be fitting to the conditions.”13

Moreover, despite the Green Book claim that it is guidance, not a standard, it is the federal design standard for the non-Interstate portions of National Highway System (NHS), a 161,000-mile system of nationally important roadways so designated by federal law. FHWA, which by statute must approve the design of roadways on the NHS, has adopted the Green Book as its standard through rulemaking.14 For cities, the percentage of urban roadways on the NHS varies considerably.

Improvements to roadways on the NHS will prioritize, almost by definition, the efficient movement of vehicles. However, FHWA’s official position is that it does not require a specific minimum level of service target for NHS projects: the recommended values in the Green Book are regarded by FHWA as guidance only. Traffic forecasts may be just one factor to consider when planning and designing NHS road improvement projects.15 What is important about this is that the principal source of design guidance for design of major highways is largely focused first on ensuring a reasonable level of service for motor vehicles. In some if not many contexts, this conflicts with the Safe System Approach, adopted as policy by FHWA: “The Safe System approach aims to eliminate fatal & serious injuries for all road users,”16 presenting a challenge to the practitioner.

___________________

11 Ibid.

12 Levels of service (LOS) first appeared in the Highway Capacity Manual of 1965 and is used in newer editions of the HCM and the Green Book, which assigns roads a letter grade between “A” and “F”—with A (free flow traffic) being the best and F (forced or breakdown flow traffic) being the worst.

13 AASHTO. 2018. Policy on Geometric Design of Highways and Streets. Table 2-5, Section 2.4.5.

14 FHWA. “Geometric Design.” Accessed May 22, 2024. https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/programadmin/standards.cfm.

15 FHWA. Memo on LOS Guidance on the NHS. May 6, 2016. https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/design/standards/160506.cfm.

16 See https://www.transportation.gov/NRSS/SafeSystem (accessed July 7, 2024).

Other Design Guides

The federal government does not require that AASHTO’s Green Book be used for road projects outside of the NHS and even allows for projects on the NHS to use other design guides under certain circumstances. Current FHWA policy is “to encourage design flexibility and full consideration of community context in transportation projects.”17 For federally funded projects, funding recipients may use “alternate” roadway design guides “recognized” by FHWA. These guides all focus on urban streets or streets that prioritize modes other than motor vehicles; safety for people walking, bicycling, or using public transit is a high priority in these guides. In addition, their use is consistent with FHWA’s policy supporting Complete Streets (see sidebar). A list of FHWA recognized guides for federally funded projects as of November 2023 is provided in Box 4-1.18 The extent to which these different design philosophies trickles down into state Departments of Transportation (DOTs) and lower-level transportation agencies varies across the nation. Box 4-1 shows alternate roadway design guides.

State DOTs and local governments also develop their own design guides, manuals, and/or requirements for road projects under their jurisdiction. Whether and how the state or local design manuals prioritize safety is up to the jurisdiction. Many local governments and some states have adopted Complete Streets design guides or requirements.19 These state and local design publications may be the nexus for innovation. For example, Washington DOT incorporated pedestrian level of stress into its design manual in 2023. Design standards for the width of sidewalks and use of street buffers advance the goal of reducing the stress on people walking caused by the amount of traffic and its speed on the adjacent road.20

Roads designed for special purposes may also have their own design guides or standards. Both the National Park Service and the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service have standards or guidelines for roads on their lands.21

___________________

17 Both the FAST Act and the IIJA/BIL provide procedures that allow the use of design guides other than AASHTO’s Green Book for federally funded road projects. See FHWA. “Design Standards, FAST Act and Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act Provisions.” November 16, 2023. https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/design/standards/231116.cfm.

18 FHWA. “Alternate Roadway Design Publications Recognized by FHWA Under BIL and FAST Act.” November 27, 2023. https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/design/altstandards/index.cfm.

19 Center for Environmental Excellence. “Connecticut DOT Adopts ‘Complete Street’ Criteria.” August 31, 2023. https://environment.transportation.org/news/connecticut-dot-adopts-complete-street-criteria. See also Ohio DOT. Multimodal Design Guide. January 19, 2024. https://www.transportation.ohio.gov/working/engineering/roadway/manuals-standards/multimodal.

20 Washington State Department of Transportation. Design Manual. October 2023. https://www.wsdot.wa.gov/publications/manuals/fulltext/M22-01/design.pdf.

21 FHWA. “Highway Design Library.” Updated April 18, 2024. https://highways.dot.gov/federal-lands/design/highway-design-library.

BOX 4-1

Alternate Roadway Design Guides for Federally Funded Projects

Under the Fixing America’s Surface Transportation (FAST) Act and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act/Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (IIJA/BIL), the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) recognizes “alternate” design guides that local jurisdictions may use for federally funded projects. These design publications may be used instead of or in addition to the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials’ (AASHTO’s) Green Book or state-adopted design manuals or standards. The following are FHWA-recognized design publications as of November 2023.

Streets

- Global Designing Cities Initiative (GDCI), Global Street Design Guide, 2016, and supplement Designing Streets for Kids, 2020.

- Institute of Transportation Engineers (ITE), Designing Walkable Urban Thoroughfares: A Context Sensitive Approach, 2010 and supplement Implementing Context Sensitive Design Handbook, 2017.

- National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO), Urban Street Design Guide, 2013.

Pedestrians

- AASHTO, Guide for the Planning, Design, and Operation of Pedestrian Facilities, 2021.

Bicyclists

- AASHTO, Guide for the Development of Bicycle Facilities, 2012.

- NACTO, Urban Bikeway Design Guide, 2014 and supplement Don’t Give Up at the Intersection, 2019.

- NACTO, Designing for All Ages & Abilities, 2014.

Transit

- AASHTO, Guide for Geometric Design of Transit Facilities on Highways and Streets, 2014.

- NACTO, Transit Street Design Guide, 2016.

SOURCE: FHWA. “Alternate Roadway Design Publications Recognized by FHWA Under BIL and FAST Act.” November 27, 2023. https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/design/altstandards/index.cfm.

FHWA’s Flexibility in Highway Design offers guidance for special purpose roads such as scenic byways and parkways.22

CRASH COUNTERMEASURES AND ROAD SAFETY PROJECTS

Crashes—or the risk of crashes—occur throughout a road network, and road safety projects primarily and directly aim to reduce the number and or the severity of crashes. Selecting, assessing, and implementing crash countermeasures are core activities of developing and delivering road safety projects. To deploy the most effective countermeasures, road safety professionals use a number of decision-making tools and operate within the framework of roadway project development.

The project development framework for crash countermeasures discussed in this section reflects the planning and project development requirements for the federal Highway Safety Improvement Program (HSIP), administered by FHWA. However, the project development process and tools outlined below could be used for any road safety project, and/or for any highway modification project that includes a road safety component.

HSIP and Road Safety Planning

While almost any federal highway funds could be used for road safety projects,23 HSIP is a core federal-aid highway program that distributes federal safety funds to state DOTs for eligible safety projects.24 HSIP represents approximately 6% of federal aid highway program funding. To spend the funds, state DOTs must produce a 5-year Strategic Highway Safety Plan (SHSP). This statewide plan, designed to reduce highway fatalities and serious injuries, identifies key safety issues and strategies to mitigate them. In addition, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act/Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (IIJA/BIL) required the SHSP to include a Vulnerable

___________________

22 FHWA. 1997. Flexibility in Highway Design. https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/environment/publications/flexibility/flexibility.pdf.

23 For each of the program categories below, up to 50% of available funding apportionment in the Federal Aid Highway Program (FAHP), exclusive of state planning and research (SPR) set-aside and penalties, may be transferred to another program category with additional limitations specific to each program category (23 U.S.C. § 126). [CMAQ, NHPP, STBG, TA, NHFP, HSIP]; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2022. Federal Funding Flexibility: Use of Federal Aid Highway Fund Transfers by State DOTs. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/26696.

24 FHWA. “Highway Safety Improvement Program (HSIP).” Updated February 2, 2024. https://highways.dot.gov/safety/hsip. For a history of HSIP, see FHWA. “About HSIP.” Updated January 31, 2023. https://highways.dot.gov/safety/hsip/about-hsip.

Road User Safety Assessment.25 The SHSP sets performance-based goals (i.e., crash/fatality reductions), and the plan is supposed to be data driven. It is to guide state investment decisions in safety projects, including those funded by HSIP. However, SHSPs do not identify specific actions to achieve the performance-based goals.26 Crash experience and/or risk levels affect selection of locations on which to focus project development. States use a variety of criteria and tools to select which crash locations and types to address. Funding and capacity limits result in decisions not to address all risk locations, and the cutoff points for excluding locations or problem types will vary across states depending on available resources and policies. For example, a state may set a strategy to reduce highway fatalities by enforcing existing motor vehicle laws and implementing countermeasures system-wide such as cable median barriers. However, states are not required in the SHSP to identify specific actions such as “install (so many) miles of cable barriers in the next two years.” Although SHSPs must include performance measures, SHSPs are not required to predict the improvements in safety that their strategies and subsequent actions seek to achieve. This makes it difficult to establish a basis for evaluating success, reducing the value of the SHSP process for state level safety management.

This disconnect extends to the guidance for preparing the HSIP. For example, when setting fatality reduction targets, the disconnect of such targets from planned programs and actions means that the targets may meet federal planning requirements but provide little or no basis for safety program planning.27 In such a situation, subsequent comparison of safety performance against prior targets would not necessarily provide a basis for planning corrective actions.

The Importance of Engineering Judgment in Selecting Crash Countermeasures

Selection of crash countermeasures relies, in part, on engineering judgment, which is called upon in much of the guidance documentation. This is because the multiple factors that go into the choice cannot be addressed

___________________

25 The six SHSP emphasis areas are distracted driving; impaired driving; infrastructure; occupant protection; pedestrians and bicyclists; and speed and aggressive driving.

26 FHWA. “Strategic Highway Safety Plan.” Updated January 18, 2023. https://highways.dot.gov/safety/hsip/shsp.

27 For example, while the U.S. DOT’s National Roadway Safety Strategy includes many laudable actions, there are no mandates for specific reductions in fatalities over a set period beyond a general, eventual goal of zero. U.S. DOT. “2024 Progress Report on the National Roadway Safety Strategy.” February 2024. https://www.transportation.gov/nrss/2024-progress-report-national-roadway-safety-strategy.

algorithmically. Although guidance calls for engineering judgment, it remains undefined.

Key underlying tasks for the practitioner are selecting countermeasures and predicting what safety outcome can be expected from their implementation at a particular location which has experienced crashes or presents major risks. Countermeasure selection depends on multiple factors, including the intervention context, impact on traffic operations, community acceptance, and the expected safety performance, or how well will the intervention work.

Expected safety performance is measured by using estimated evidence-based crash modification factors (CMFs), identified as either point estimates or ranges. Underlying these estimates is a distribution of possible outcomes, or forecasts. To select appropriate CMFs, practitioners should compare the context where research studies to the case at hand. This is based on judgment on the part of the practitioner to evaluate the available evidence and find a sufficiently trustworthy CMF that is applicable to the proposed countermeasure and location of interest.

The task is made more difficult where the research evidence is either weak or non-existent (information about the research sources is available in the CMF Clearinghouse), or where the context of the research studies is a poor match to the application setting. In these situations, the countermeasure and CMF selection process must rely on engineering judgment and, ultimately, by more and better research on the effectiveness of such interventions.

Exploring the requisites for engineering judgment, Hauer writes that:

for a judgment to be of the engineering kind it must be made by an engineer whose competence is in the subject matter about which the judgment is rendered. Competence is rooted in knowledge and the ability to identify and evaluate the available evidence and to integrate it into a judgment. To be competent in road safety, the engineer has to know the facts needed to foresee the safety consequences of choices and decisions.28

Thus, engineering judgment requires technical knowledge of factors affecting safety outcomes and evidence matching the context of research settings to the situation at hand, and the ability to interpret the two. The demands on the practitioner are substantial, underscoring the importance of in-depth education as discussed at the end of this chapter.

___________________

28 Hauer, E. 2019. “Engineering Judgment and Road Safety.” Accident Analysis and Prevention 129:180–189. The ability to foresee the safety consequences of engineering decisions is an underlying principle of evidence-based road safety research.

Road Safety Project Development

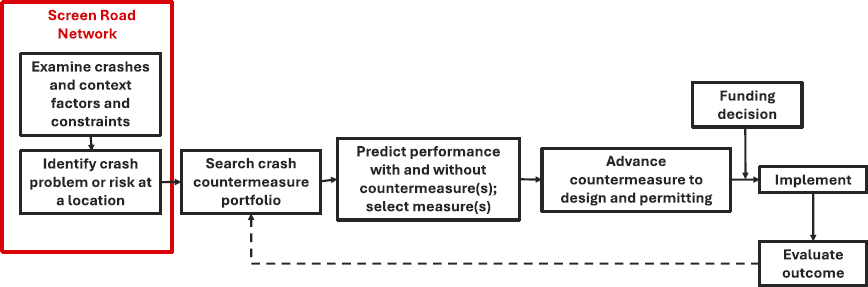

To spend HSIP funds, state DOTs must create a prioritized list of highway safety improvement projects. During this priority-setting phase, analyzing countermeasures based on their safety performance becomes critical because, in essence, this should guide how the state DOT allocates its HSIP funds. Data-driven safety analysis (DDSA) is required for projects eligible for HSIP funds.29 Figure 4-1 describes the project development process for a highway safety project. This figure details Phase II of Figure 3-1, amplifying the processes connecting identification of road safety problems and countermeasure implementation.

Network screening identifies safety problems and locations considering performance measures, including crash frequency, crash rate, equivalent property damage only (EPDO), and others.30 Screening can be performed at various levels of detail and sophistication. More advanced screening methods included in the HSM account for traffic volume trends and the effect of regression to the mean to avoid overweighting short-term crash spikes by considering average rates at similar sites;31 and the application of Safety Performance Functions calibrated for a particular state that account for local experience. Specific user groups (e.g., pedestrians) or crash types (e.g., roadway departures) may also be selected for particular attention. The more advanced screening criteria are sensitive to more factors contributing to crashes and reflect risk as well as actual crash experiences, but they are also more demanding of data and efforts of the practitioner.32 Multiple screening criteria are sometimes applied to increase confidence in selection of target sites for study and selection of countermeasures.

For a given location with a safety problem, the road safety practitioner searches portfolios of countermeasures for interventions that fit the problem and the specific road context. The practitioner then must use available guides and tools to predict the safety performance of the road with and without the countermeasure for the purpose of evaluating candidate countermeasures (see Figure 4-1). This task is complicated because it must consider data describing crash events, roadway design and contextual data and location, vehicle and driver data, data about vulnerable road users, and

___________________

29 FHWA. “Data-Driven Safety Analysis.” Updated December 27, 2023. https://highways.dot.gov/safety/data-analysis-tools/rsdp/data-driven-safety-analysis-ddsa.

30 Highway Safety Manual, per comment H74.

31 Regression to the mean is the phenomenon in a stream of random variables such as annual traffic crash counts for an occasional extreme value to be offset by a return to a long-term trend or mean value. Controlling for regression using a method such as empirical Bayesian analysis avoids bias in results coming from rare extreme values.

32 Road Safety Professional Capacity Building Program (RSPCBP). “UNIT 4. Solving Safety Problems.” Road Safety Fundamentals. June 2017. https://rspcb.safety.fhwa.dot.gov/RSF/Unit4.aspx.

data describing the efficacy of potential crash countermeasures. A range of safety products (guidance and analysis tools) are available to support selection of crash countermeasures and to evaluate their effectiveness. The variety of support resources is such that practitioners sometimes need guidance on selecting them (see Box 4-2).

The road segment and selected countermeasure(s) then become a proposed safety project that moves through the process of design and permitting, awaits the funding decision, and then is implemented. Ideally, the project would also undergo a post-implementation evaluation, with the results informing the crash countermeasure portfolio.

AASHTO’s Highway Safety Manual

AASHTO’s Highway Safety Manual (HSM), first published in 2010, is a prominent source of guidance for road safety planners and engineers. The multi-volume manual provides comprehensive and extensive guidance on incorporating quantitative safety analysis into road safety project planning and development and network safety management. It covers the safety management process as described in the HSM from network screening to post-implementation evaluation and contains procedures for predicting expected safety performance of roadway sections and intersections without and with proposed countermeasures. The HSM does not include tools and methods such as IHSDM and spreadsheets and for estimating expected crash reductions for specific countermeasures.33 Such tools are provided by FHWA, AASHTO, and state-generated spreadsheet tools as mentioned on p. 68. The second edition of the Highway Safety Manual (HSM2) is expected to be published in late 2025, 15 years after the first version.34

The most complicated methods in the manual, and the most valuable for improving safety, are the methods for predicting the annual number of crashes on a roadway segment or intersection.35 The analysis is highly technical and depends upon knowledge of the statistical methodology and appropriate skills (either from agency staff or consultants) and the availability of roadway inventory data. The predictive methods relate the traffic volume to the number of crashes for a given roadway segment or intersection with

___________________

33 AASHTO. “Highway Safety Manual—About.” Accessed March 29, 2024. https://www.highwaysafetymanual.org/Pages/About.aspx.

34 See https://www.highwaysafetymanual.org/Documents/AASHTO_HSM2_Update_webinar_20240618_Combined.pdf.

35 Observed crashes are those documented at a particular site of interest; predicted crashes are estimates calculated using a Safety Performance Function; expected crashes are a combination of observed and predicted. Safety Data and Analysis: Observed, Predicted and Expected Crashes. 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fTzz5bv7Ko8.

a given set of characteristics. The analyst can use these predictive methods to estimate the change in crash frequency or severity—the benefit—likely to come from the implementation of either a safety countermeasure or a change in characteristics of the roadway element.36 Because predictive methods can estimate the crash frequency on a segment or intersection that remains unchanged, they can identify segments and intersections with that may have excess crashes in the future.

The HSM has been criticized for its overlapping and inconsistent planning requirements, complicated and labor-intensive methods, weak application guidance, and incomplete illustrative case studies.37 The key gaps agencies face in using HSM procedures include the following:

- Multi-step and cumbersome processes required for predictive analysis (roadways must be divided into segments and intersections, the segments into sections with homogenous characteristics with separate calculations required for each section and intersection).

- Significant time and effort required to learn to apply these techniques and limited availability of detailed training resources.

- Limited availability of tools (software) to support HSM analyses.

- Need for specialized guidance when unusual or undocumented situations are encountered.

- Limited availability of trained and experienced staff dedicated to safety analysis.

- Limited availability of detailed and timely data including traffic volumes, crash data, and roadway design and traffic control features.

While the HSM contains procedures to adjust predictions for different states (i.e., calibration factors38), some states and local jurisdictions have also developed their own safety spreadsheet tools and applications to make more useful (but not necessarily more rigorous) safety predictions for their unique conditions and to create “workarounds” to implement the HSM.39,40

___________________

36 Singh, J. Presentation to the committee. November 30, 2022.

37 Ibid.

38 For an example, see Ohio DOT. “Safety Analysis Guidelines.” November 15, 2022. https://www.transportation.ohio.gov/programs/Highway+Safety/highway-safety-manual-guidance/safety-analysis-guidelines-cf.

39 NJDOT surveyed six state DOTs and developed its report on predictive safety tool research in January 2023. See Hopwood, C., and M. Motamed. 2023. Predictive Safety Tool Research. NJDOT, Bureau of Research. Final Report, NJ-2023-001.

40 Singh, J. Presentation to the committee. November 30, 2022.

Although its contents are of high value, the complicated nature of the HSM presents a challenge even to experienced safety-focused engineers.41

Crash Modification Factor Clearinghouse

A crash modification factor (CMF) is defined as the long-term number of crashes (of a particular type) with a countermeasure in place divided by the long-term average number of crashes without the countermeasure in place.42 For a countermeasure that is expected to reduce the number of crashes, the CMF will be less than one. The CMF Clearinghouse is an FHWA-sponsored online repository of CMFs that is regularly updated and also presents educational material for road safety professionals.43 The Clearinghouse contains relationships between listed countermeasures and more than 8,300 CMFs, which differ not only by countermeasure but also by traffic volumes, roadway geometry and configuration, location, and context. However, the CMF Clearinghouse is not comprehensive, representing only a fraction of the available countermeasures, the type of crashes they target, and the contexts in which they may be deployed.

The content of the Clearinghouse is limited by the research results available in the literature. The CMFs are the products of independent research studies evaluating the implementation of specific countermeasures in different places. CMFs may be developed by considering the results from multiple studies (preferred) or by only a single report. A given countermeasure may have a range of CMFs associated with it that differ in contexts and designs, by crash severity and type or by the quality of the underlying research (e.g., sampling and analysis methods). Each CMF in the Clearinghouse is scored based on the confidence in its value using a scale of one to five stars, with four stars representing high confidence in the validity of the research backing the CMF.44 The collection of CMFs is updated at least annually.

CMFs estimate the efficacy of the countermeasure, and the practitioner may test multiple countermeasures to determine which is most

___________________

41 AASHTO. “Safety-Focused Engineers Are the HSM’s Target Audience.” Highway Safety Manual—FAQs.” Accessed April 30, 2024. https://www.highwaysafetymanual.org/Pages/support_answers.aspx#4.

42 FHWA. “Safety Data and Analysis: Application of CMFs.” Accessed May 15, 2024. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SjYlNcg841A.

43 The CMF Clearinghouse is funded by FHWA and managed by the University of North Carolina Highway Safety Research Center. As of May 12, 2024, CMFs were last added to the clearinghouse on January 19, 2024. See “Crash Modification Factor Clearinghouse.” Accessed May 12, 2024. https://www.cmfclearinghouse.org.

44 For more information on the methodology behind the ranking system, see “CMF Clearinghouse.” Accessed March 29, 2024. https://www.cmfclearinghouse.org/sqr.php.

cost-effective.45 Analyzing the appropriate countermeasures for a specific location and/or problem calls for a practitioner with skills, knowledge, and experience, and there is a need in the road safety community for bridging tools to support this process.46 Indeed, some agencies rely on consultants to provide this expertise in the form of guidance or a short list of recommended CMFs.47 Countermeasures with a weak evidence base present an obstacle for the practitioner. For example, there may not be a high-validity countermeasure that fits the context.48 The CMF Clearinghouse contains conflicting information about the expected performance of crash countermeasures, indicative of the database’s reliance on information that is inconsistently supported by evidence-based research.

Development of Crash Modification Factors Program

FHWA conducts its own research on crash countermeasures and their effectiveness and develops CMFs under the Development of Crash Modification Factors (DCMF) Program, run by the Turner-Fairbank Highway Research Center. This program identifies CMF research needs, develops CMFs for the Highway Safety Manual, and promotes promising safety improvements. To develop CMFs, they develop and advance statistical methodologies that evaluate countermeasure deployments.49

Forty-one state DOTs participate in funding the Evaluation of Low-Cost Safety Improvements (ELCSI) Pooled Fund Study, which corroborates the research-based assessment of selected, inexpensive crash countermeasures. The member states regularly advise the DCMF Program.50

___________________

45 “Road Safety Fundamentals Unit 4: Solving Safety Problems.” Accessed March 28, 2024. https://highways.dot.gov/safety/learn-safety/road-safety-fundamentals-html-version/unit-4-solving-safety-problems.

46 Polin, B., HSIP Manager, MassDOT Highway Safety Program. Presentation to the committee. November 4, 2022.

47 Regional Safety Strategy, Atlanta Regional Commission, 2022, Appendix D, CMF Short List.

48 Aside from data gaps, this complex, multifactor countermeasure selection process may be an opportunity to develop artificial intelligence tools to support practitioners.

49 FHWA. “Development of Crash Modification Factors (DCMF) Program.” Updated September 19, 2023. https://highways.dot.gov/research/safety/development-crash-modificationfactors-program/development-crash-modification-factors-dcmf-program.

50 FHWA. “Evaluations of Low-Cost Safety Improvements Pooled Fund Study (ELCSI–PFS).” Updated September 19, 2023. https://highways.dot.gov/research/safety/evaluations-low-cost-safety-improvements-pooled-fund-study/evaluations-low-cost-safety-improvements-pooled-fund-study-elcsi%E2%80%93pfs.

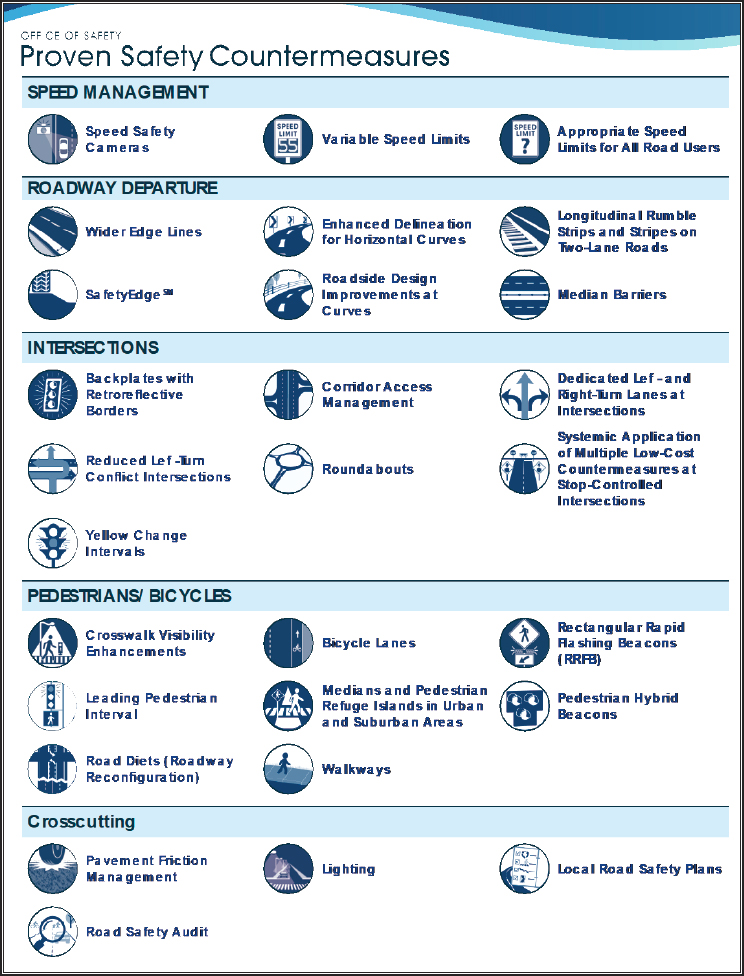

Proven Safety Countermeasures

Since 2008, FHWA has promoted a subset of countermeasures that offer “significant, measurable impacts” as part of its Proven Safety Countermeasures initiative. Updated every 4–5 years based on a review of research, the cumulative list now has 28 countermeasures deemed suitable for widespread use (see Figure 4-2). However, 6 of the 28 proven countermeasures are based on only a single study. These are:

- Rectangular rapid flashing beacons

- Medians and pedestrian refuge islands

- Walkways

- Road diets

- Road safety audits

- Traffic signal backplates with retroreflective borders

The safety benefits of retroreflective border backplates are only supported by a single 2005 study that was never formally published.51 Despite this, reflective border backplates have been adopted by many state DOTs and local jurisdictions.

Countermeasure Deployment Challenges

To translate research findings into practice, road safety practitioners face a daunting set of tasks, dominated by multiple challenges, including steep learning curves, the need for specialized training, and a continued reliance on engineering judgment.

Selecting the Appropriate Countermeasure is Complicated

As previously described, the current data capabilities, guidance, and analysis requirements are often the main sources of challenges for the practitioner. The HSM and CMF Clearinghouse are based on important principles of road safety science and comparative evaluation. Knowledge of and comfort with use of the concepts and methods is critical to effective analysis, evaluation, and decision support. While it is not necessary that every safety professional understand the statistical intricacies of counterfactual analysis (expected roadway performance with and without a particular

___________________

51 See Sayed, T., P. Leur, and J. Pump. 2005. “Safety Impact of Increased Traffic Signal Backboards Conspicuity.” TRB 84th Annual Meeting: Compendium of Papers CD-ROM, Vol. TRB#05-16, Washington, DC.

SOURCE: FHWA. “Making Our Roads Safer: One Countermeasure at a Time.” October 2021. https://highways.dot.gov/sites/fhwa.dot.gov/files/Proven%20Safety%20Countermeasures%20Booklet_0.pdf.

countermeasure), it is necessary for all safety professionals to have a grasp of the importance of the core HSM analysis paradigm as reflected in Figure 4-1.52

Reliance on Multiple Analysis Tools

The need for DDSA to make projects eligible for HSIP funds has led to a mushrooming of safety analysis tools, which have become essential to choosing safety countermeasures. While the HSM is a core resource, its complicated nature has led state DOTs, AASHTO, software companies, and others to develop their own tools (see Box 4-2 for review of analysis tools conducted for the New Jersey Department of Transportation [NJDOT]). Choosing which tools to use is not straightforward because there are so many options. There are currently more than 160 tools listed on FHWA’s DDSA website, the majority of which are application and information guides, including manuals, protocols, and methods for a variety of different topics.53 Examples include data collection manuals, best practices for safety and planning, evaluation or self-assessment guides, performance

BOX 4-2

Analyzing Safety Tool Selection Among Practitioners

The New Jersey Department of Transportation (NJDOT) researched the predictive safety analysis tools available in the market and how they are being used by state Departments of Transportation (DOTs). These tools have proliferated since the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO) released the Highway Safety Manual (HSM) in 2010. NJDOT sought to understand the benefits, limitations, and paths to implementation for the tools currently in use. The study found that there were numerous tools in use, and some agencies use multiple tools. Tools covered include AASHTOWare Safety Analyst, AASHTOWare Safety Powered by Numetric, Inc., DOT Network Screening Tools, State-Specific Safety Performance Factors (SPFs), DOT and AASHTO Spreadsheets for Predictive Analysis, Interactive Highway Safety Design Model (IHSDM) and Enhanced Interchange Safety Analysis Tool (ISATe).

SOURCE: Hopwood, C., and M. Motamed. 2023. Predictive Safety Tool Research. NJDOT, Bureau of Research. Final Report, NJ-2023-001.

___________________

52 AASHTO, Highway Safety Manual, particularly the relationship between safety performance and functions to quantify it along with crash modification factors which quantify the effectiveness of countermeasures.

53 FHWA. “Roadway Safety Data Program Tools.” https://highways.dot.gov/safety/data-analysis-tools/rsdp/rsdp-tools.

measures, management methods, and benefit-cost analysis methods. Other tools listed include databases, crash or fatality reports, mitigation strategies, and monitoring or information systems. Finally, there are software tools to help practitioners perform safety or crash analyses, use management systems, develop decision trees, conduct cost-benefit analysis, and develop models for traffic and safety design. While software developed by FHWA or NCHRP is free and available to the public, many products developed by private companies and by AASHTO must be purchased. Several states also have free software, but some only provide the software to state government agencies or those working for the state.

Building Safety into Every Highway Project

While federal support is focused through specific funding programs, notably the HSIP, the committee observed that there are opportunities to invest in safety improvements in many different types of highway projects. Flexibility in the use of federal funds generally permits this. Taking advantage of these opportunities for synergies is a way to extend the reach of road safety programs.

The first of three sidebars illustrating ways to advance road safety at the local level tells how the City of Atlanta used the opportunity of a major resurfacing program to improve road safety in communities through a Complete Streets implementation.

Supporting Local Countermeasure Experimentation

While safety research and implementation are distinctly separate activities, practitioners may be the first to face real road safety problems, and they are sometimes under pressure act even when evidence-based countermeasures do not exist. While normal policy and procedures discourage going beyond the established evidence of countermeasure efficacy, the committee discovered multiple examples of practitioners going “beyond the book” to address problems. These sometimes seemed like opportunities to engage in field experimentation that could advance road safety. The sidebar below describes this opportunity.

A second sidebar below illustrates how practitioners are contributing to road safety innovation through initiatives to address local problems, and how their work might be drawn into a more formal research effort.

A third example of grass roots innovation, in the sidebar below, describes a city-wide government-industry-academia collaboration in Bellevue, Washington, that supports its Vision Zero initiative by testing advanced detection and analysis technologies for both operations management and research.

SIDEBAR

Combining Complete Streets Implementation with Road Resurfacing

There are opportunities to advance road safety in almost every highway project. The city of Atlanta used its local road resurfacing program to address systemic community safety issues.a As part of this project, planners evaluated crash trends, multimodal traffic volumes, bicycle rider level of stress, and travel time reliability to develop road designs consistent with the Georgia Department of Transportation’s (DOT’s) Complete Streets Policy.b Taking advantage of a region-wide, data-driven road safety study conducted for the Atlanta Regional Commission,c the Atlanta DOT looked to NACTO and Georgia DOT design guidelines to introduce actions to protect vulnerable road users by adding and improving bicycle lanes and sidewalks in seven downtown corridors. Atlanta DOT officials accomplished this work through collaboration and community outreach, building partnerships with the downtown business district, advocacy groups, a city council member, the Atlanta Regional Commission, and Georgia DOT. The collaboration involved some give-and-take between Georgia DOT and Atlanta DOT, which led to designs that prioritized the safety of vulnerable road users while acknowledging the importance of vehicle service levels.

__________________

a The city of Atlanta resurfaces 3–4 streets out of 50 streets every year with resurfacing grant funds.

b Georgia DOT’s policies for Complete Streets are detailed in Chapter 9 of the Design Policy Manual and support Complete Streets in urbanized areas statewide. “Complete Streets is more than pages in a manual ... [it] is confirmation of an ever-changing culture [and] an acknowledgement that our transportation system can be more – should be more – than its least common denominator; a recognition that the straightest route between two points may not be everyone’s desired route” (GDOT Chief Engineer Gerald Ross, 2012).

c Atlanta Regional Commission, Regional Safety Strategy, 2022.

SIDEBAR

When Deployment Gets Ahead of the Evidence: Complete Streets, Laboratories for Innovation

According to the National Complete Streets Coalition, Complete Streets is “an approach to planning, designing and building streets that enables safe access for all users, including pedestrians, bicyclists, motorists and transit riders of all ages and abilities.”a Complete Streets operates at the policy level, and the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) advocates that transportation agencies should make Complete Streets “the default approach” to their street networks.b The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act/Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (IIJA/BIL) set aside funding for states and Metropolitan Planning Organizations to adopt Complete Streets policies, standards, and prioritization plansc and included a new $5 billion Safe Streets and Roads for All grant program to fund regional, local, and Tribal governments for safe streets planning and projects.d

Design Flexibility and Proven Countermeasures

A Complete Streets project is almost never a single safety intervention. Instead, such projects typically take a more holistic approach and upgrade a corridor or neighborhood to make it safer and easier to walk, bicycle, use mobility devices, and access mass transit. From the road design perspective, a Complete Streets project involves a combination of actions customized to fit a particular setting.

Because traditional sources of standards and guidance (the Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices, the AASHTO Green Book, the Highway Safety Manual, and the Crash Modification Factors [CMF] Clearinghouse) have been inadequate to accomplish Complete Streets project objectives, FHWA points to its recognized alternate design publications for streets, pedestrians, bicyclists, and transit listed in Box 4-1.e However, it can be difficult to assemble the evidence to show that the multiple crash countermeasures deployed for a typical Complete Streets project are “proven,” Although CMFs are available for some

__________________

a National Complete Streets Coalition. “Complete Streets.” Accessed May 10, 2024. https://smartgrowthamerica.org/what-are-complete-streets.

b FHWA. “Complete Streets in FHWA.” Accessed May 10, 2024. https://highways.dot.gov/complete-streets.

c FHWA. “Waiver of Non-Federal Match for State Planning and Research (SPR) and Metropolitan Planning (PL) Funds in Support of Complete Streets Planning Activities (BIL § 11206).” January 5, 2023. https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/planning/spr-pl_match_waiver_memo.pdf.

d U.S. DOT. “Safe Streets and Roads for All (SS4A) Grant Program.” Updated April 16, 2024. https://www.transportation.gov/grants/SS4A.

e FHWA. “Complete Streets in FHWA.” Accessed May 10, 2024, https://highways.dot.gov/complete-streets.

project components, others need further research.f Moreover, when analyzing a multicomponent intervention, there is not yet a strong theoretical basis for combining CMFs to produce a reliable prediction of the safety outcome.g This is illustrated by FHWA’s use of Complete Streets project case studies rather than analytical research for explanation and evaluation.h

The limitations of available design guidance have led some municipalities and state DOTs to develop their own Complete Streets design guides.i These are typically built on qualitative, “good” design practices, local experience, and innovations arising from practitioners faced with problems and the responsibility to address them. In this process, conflicts can arise between the need to balance implementing Complete Streets projects and the responsibility to find and implement proven (research-based) countermeasures. Faced with the lack of research results, the practitioner may be caught between national policies that support both Complete Streets and the search for evidence-based countermeasures, while striving to solve real local safety problems.

__________________

f The CMF Clearinghouse contains 439 CMFs under its category of “Complete Streets”; see CMF Clearinghouse, “Search Results: Complete Streets.” Accessed May 12, 2024. https://www.cmfclearinghouse.org/results.php?qst=complete%20streets.

g Gross, F., and A.J. Hamidi. “Investigation of Existing and Alternative Methods for Combining Multiple CMFs.” CMF Clearinghouse. June 30, 2011. https://www.cmfclearinghouse.org/collateral/Combining_Multiple_CMFs_Final.pdf.

h FHWA. “Implement Complete Streets Improvements.” Accessed March 11, 2024. https://highways.dot.gov/complete-streets/implement-complete-streets-improvements.

i For an example, see NYC DOT. “Street Design Manual.” Accessed May 10, 2024. https://www.nycstreetdesign.info.

FHWA is sponsoring a variety of initiatives to build a knowledge base, including CMFs, to support Complete Streets objectives, but this need has not yet been fulfilled.j

This conflict between advancing the Complete Streets approach and ensuring the use of proven countermeasures can lead to challenges for practitioners or local advocates who seek to solve real problems with under-researched solutions. As TRB’s Research and Technology Coordinating Committee, an advisory committee for FHWA, reports:

Over time, FHWA has broadened its guidance about design as a way to encourage states to use engineering judgment to apply different designs in different contexts. It was noted, however, that the application of this flexibility can lead to inconsistent interpretations of requirements that lead to missed opportunities to address safety for all users. For instance, local proponents of context-sensitive and safety-enhancing designs that are not common practice in their jurisdiction may be asked by federal or state reviewers to provide additional analysis or justification. Such added burdens can discourage the pursuit of such solutions even when they are allowable under the flexible guidance.k

FHWA’s endorsement of “flexibility” in design may just result in demands for “additional analysis and justification,” perhaps in situations where there is little or no analysis available to support an innovative safety design.

__________________

j Research and Technology Coordinating Committee (RTCC). “Letter Report.” September 29, 2022. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/26758.

k RTCC. “Letter Report.” September 29, 2022. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/26758/research-and-technology-coordinating-committee-letter-report-september-29-2022.

SIDEBAR

Using Streets as Laboratories for Innovation

Local streets can serve as laboratories for road safety innovations at the practitioner level, leading responsible professionals to reach beyond proven guidance.a This is a natural part of the innovation process: problems beget creativity, and creativity creates research needs. Field implementation, then, creates the research opportunity. This coincides with the research translation process (described in Chapter 5) that cycles among real problems, field applications, and research. The challenge is to bring these innovations under the umbrella of road safety science by designing and evaluating natural experiments and conducting valid research to assess outcomes.

Creating a process where design innovations become field experiments can also address data limitations, which are viewed as obstacles to increasing investments in bicycle and pedestrian facilities.b The absence of data documenting pedestrian and bicycle activity may be caused by the absence of activity or the failure to collect utilization data. Even the absence of observed pedestrian and bicycle activity does not necessarily prove a lack of demand; it may indicate a lack of supply of safe facilities. These are challenges that can be overcome through experimentation, sometimes with low-cost, temporary facilities than can be easily modified or removed.c

Two examples illustrate the value of locally devised countermeasures that were deployed to address problems, at first without supporting evidence:

The HAWK (High-Intensity Activated Crosswalk) was developed in Tucson, Arizona, in the 1990s to help pedestrians cross busy and wide streets that were otherwise without controls. Now known as the Pedestrian Hybrid Beacon (PHB), the device is

__________________

a Keierleber, Brian, Buchanan County Iowa; Smoot-Madison, Betty, City of Atlanta; Viola, Rob, New York City DOT. Presentations to Committee in 2023.

b RTCC. “Letter Report.” September 29, 2022. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/26758.

c For example, Atlanta DOT designated temporary sidewalks with traffic cones. Presentation to the committee, June 8, 2023.

activated by pedestrians, and it displays two side-by-side red signals to approaching traffic. Subsequent statistical evaluation provided evidence for the effectiveness of the PHB, and it was adopted into the MUTCD in 2009.d

The Rectangular Rapid Flashing Beacon (RRFB), another pedestrian-activated warning device for pedestrian crossings, was first deployed in St. Petersburg, Florida, in the 2000s and, based on subsequent studies to establish its effectiveness, was given interim FHWA approval in 2008.e After issues regarding patents were resolved, FHWA reissued its approval in 2018. In both cases, safety evaluations were conducted after a number of devices had been installed and evaluated to determine their effectiveness.

Rather than discouraging innovations because of lack of evidence, there is an opportunity to integrate practitioner-led innovations into a national research program to build the knowledge base that will strengthen guidance for implementing Complete Streets and other safety policies and crash countermeasures. This requires funding for data collection and research, as well as guidance for conducting quality research. As described in Chapter 5, innovations often arise in the medical field and move upstream into research to build the evidence for efficacy. This process is built into the research translation process, and, with an appropriate degree of control, is encouraged. Such practitioner-led innovations are known in the medical practice as emerging strategies or best practices until the body of evidence develops.

__________________

d Wells, J.M., et al. “Pediatric Emergency Department Visits for Pedestrian Injuries in Relation to the Enactment of Complete Streets Policy.” Frontiers in Public Health 11 (August 2023). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1183997. See also Mooney, S.J., et al. “Complete Streets and Adult Bicyclist Fatalities: Applying G-Computation to Evaluate an Intervention That Affects the Size of a Population at Risk.” American Journal of Epidemiology 187(9): 2038–2045 (September 2018). https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwy100.

e Fitzpatrick et al. “Will You Stop for Me? Roadway Design and Traffic Control Device Influences on Drivers Yielding to Pedestrians in a Crosswalk with a Rectangular Rapid-Flashing Beacon.” Report no. TTI-CTS-0010. Texas A&M Transportation Institute, 2016.

SIDEBAR

Advancing Road Safety Through Community Innovation: Bellevue, Washington

To achieve its goal of eliminating traffic deaths and serious injury collisions on city streets by 2030, the city of Bellevue, Washington, adopted the Safe System Approach (SSA) after which a Vision Zero Strategic Plan was developed that articulates a coordinated approach across city departments.a City staff now develops annual action plans to keep Bellevue’s program on track and monitor progress.

These actions provide the context for creating a testbed for experimenting with video analytics technologies to measure program performance, identify road safety risks, and evaluate countermeasure effectiveness.b Capabilities have been amplified through innovative partnerships with technology companies, research institutions, and nonprofit organizations, which contribute equipment and analysis capabilities.c A network of 360-degree, high-definition traffic cameras has been deployed at signalized intersections to identify the frequency and severity of near-crash traffic conflicts between people driving, walking, and bicycling.d

The insights derived from processing video with artificial intelligence algorithms enhance Bellevue’s road safety decision-making, identifying problem areas, selecting appropriate safety countermeasures, prioritizing investments in improvements, and monitoring the impacts of countermeasures. For example, the city leveraged a network-wide conflict analysis that identified high-risk intersections and made traffic signal operations changes that led to a 60% reduction in critical conflicts at test intersections.e

Continuing to pursue ways to protect vulnerable road users, Bellevue used its video analytics testbed to conduct a Leading Pedestrian Intervals (LPI) pilot study, allowing pedestrians to get a head start on street crossings, and found a 42% reduction

__________________

a City of Bellevue. “Vision Zero.” Accessed April 19, 2024. https://bellevuewa.gov/city-government/departments/transportation/safety-and-maintenance/traffic-safety/vision-zero.

b City of Bellevue. “Progress Reporting.” Accessed April 19, 2024. https://bellevuewa.gov/city-government/departments/transportation/safety-and-maintenance/traffic-safety/vision-zero/video-analytics.

c Franz Loewenherz, Franz, Bahl, Victor, and Yang, Yinhai. Video Analytics Towards Vision Zero. ITE Journal vol. 87, no. 3 (March 2017). https://bellevuewa.gov/sites/default/files/media/pdf_document/video-analytics-toward-vision-zero-ITE-Journal-article-March-2017.pdf.

d Lana Samara, Paul St-Aubin, Franz Loewenherz, Noah Budnick, and Luis Miranda-Moreno, Video-based Network-wide Surrogate Safety Analysis to Support a Proactive Network Screening Using Connected Cameras: Case Study in the City of Bellevue (WA) United States, August 2020. https://bellevuewa.gov/sites/default/files/media/pdf_document/2020/TRB-Accepted-Paper-2021-Video-Surrogate-Safety-Analysis-Bellevue.pdf.

e Lana Samsara, Lana et al. Video-based Network-wide Conflict Analysis to Support Vision Zero in Bellevue (WA) United States: Conflict Analysis Report. July 2020. VZ-ITS-Bellevue-Report-1-web.pdf (bellevuewa.gov).

in vehicle–pedestrian conflicts.f,g These evidence-based intervention results led Bellevue to expand the use of LPIs throughout its downtown area. Later, the city completed a before-after evaluation on the safety impacts of high visibility crosswalk pavement markings and found a 56% reduction in vehicle–pedestrian conflicts, leading the city to include this countermeasure as standard practice in its design manual.h

These initiatives have paved the way to a new safety collaboration, the Real-Time Traffic Signal Safety Interventions Project, which will combine data from connected vehicles, video cameras, LiDAR sensors, and smartphones and identify safety problems. Real time alerts are issued to road users and the city’s adaptive signal control system to initiate proactive signal adjustments and reduce the frequency and severity of crashes.i

Achievements in Bellevue demonstrate the value of a political commitment to SSA in providing context for collaborations, comprehensive management of the road safety program, and experimentation with innovative tools. City government has built on these collaborations to create a test bed environment for conducting research on crash causation and testing countermeasure effectiveness. Funds came from the City of Bellevue, the State of Washington, the federal government, along with support from private sector partners.

This case illustrates ways in which local agencies can be a source of countermeasure and methods innovation through partnerships with technology companies and creative use of funds from local, state and federal sources. To ensure the validity of findings of locally based research, it is important to conduct high quality research using appropriate tools and methods, as illustrated in the Bellevue program. One way to ensure this is to partner with capable research entities, including academic institutions. Bellevue’s integrated approach to Safe System actions—implementing safer roadways, managing speeds, generating better data, and collaborating with the private sector on innovative technology solutions—has resulted in a lower per-capita rate of fatal and serious injury collisions than other cities in Washington state.

__________________

f Ashutosh Arun, Md. Mazharul Haque, Craig Lyon, Tarek Sayed, Simon Washington, Franz Loewenherz, Darcy Akers, Mark Bandy, Victor Bahl, Ganesh Ananthanarayanan, and Yuanchao Shu, Leading Pedestrian Intervals – Yay or Nay? A Before-After Evaluation using Traffic Conflict-Based Peak Over Threshold Approach. February 2022. https://bellevuewa.gov/sites/default/files/media/pdf_document/2022/leading-pedestrian-intervals-research-paper-010322.pdf.

g Mark Bandy and Erica Tran, Jacobs Engineering Group for the City of Bellevue, Microsoft, and Advanced Mobility Analytics Group, Evaluation of Leading Pedestrian Intervals Using Video Analytics, March 2022, https://bellevuewa.gov/sites/default/files/media/pdf_document/2022/City-of-Bellevue-LPI-Video-Analytics-Summary-Evaluation-05082022-final.pdf.

h Fehr & Peers. “Evaluation of High Visibility Crosswalks Using Video Analytics.” August 2023. https://bellevuewa.gov/sites/default/files/media/pdf_document/2023/Evaluation%20of%20High%20Visibility%20Crosswalks%20Using%20Video%20Analytics.pdf.

i City of Bellevue, Real-Time Traffic Signal Safety Interventions (RTSSI) Projects, October 2023. https://bellevuewa.gov/sites/default/files/media/pdf_document/2024/Bellevue%20RTSSI_SMART%20%20FY23.pdf.

NATIONAL HIGHWAY TRAFFIC SAFETY ADMINISTRATION AND BEHAVIORAL COUNTERMEASURES THAT WORK

Federal funding for behavioral safety programs flows through NHTSA to State Highway Safety Offices.54 To secure NHTSA-administered safety funding, each State Highway Safety Office must submit for approval a Highway Safety Plan (HSP) that identifies highway safety problems, establishes performance measures, and targets, and specifies the state’s countermeasure strategies and projects to achieve its performance targets. The IIJA/BIL requires the plan to be a 3-year document, now called the Triennial Highway Safety Plan.55 The HSP also documents the state’s efforts to coordinate the HSP with the state Strategic Highway Safety Plan (SHSP) (the FHWA requirement discussed earlier in this chapter), including their data collection and information systems. One significant unresolved issue is how the SHSP performance-based goals align with the HSP performance-based targets.56 To prepare HSPs, states evaluate traffic crash data and identify the most prevalent factors affecting motor vehicle crashes. States then develop their own programs for allocating highway safety funds to areas with the most problems, targeting locations and actions likely to reduce the most fatal and serious crashes. That the NHTSA and FHWA safety programs have separate planning requirements to secure funding risks missing opportunities for creating integrated solutions to road safety problems.

The state HSPs identify countermeasures from NHTSA’s publication Countermeasures That Work (CTW), currently in its 11th edition.57 CTW is a “reference guide” designed “to help select effective, science-based traffic safety countermeasures to address highway safety problem areas.” It covers 11 major behavioral safety topics and typically identifies multiple countermeasures for each. For each countermeasure, the guide describes its use, effectiveness, cost, and implementation time. Effectiveness is rated on

___________________

54 Section 402: State and Community Highway Safety Grant Program, and Section 405: National Priority Safety Program are the two main NHTSA-administered road safety grant programs. For a list of behavioral safety and related grant programs under IIJA/BIL, see GHSA. “Federal Grant Programs.” Accessed May 10, 2024. https://www.ghsa.org/about/federal-grant-programs. Some highway safety offices are located within the state DOT, while others are separate agencies within the governor’s office.

55 See, for example: DCDOT Triennial Plan. July 2023. https://www.nhtsa.gov/sites/nhtsa.gov/files/2023-10/DC_FY24HSP-tag.pdf.

56 FHWA and NHTSA waived the requirement that the two state highway safety plans have identical performance targets for FY 2025; see “Uniform Procedures for State Highway Safety Grant Programs,” 89 FR 37113. May 6, 2024. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2024/05/06/2024-09732/uniform-procedures-for-state-highway-safety-grant-programs.

57 https://www.nhtsa.gov/book/countermeasures/countermeasures-that-work (May 24, 2024). NHTSA. 2023. Countermeasures That Work, 11th edition. Accessed May 24, 2024. https://www.nhtsa.gov/book/countermeasures/countermeasures-that-work.

a one- to five-star scale. Cost is rated using dollar signs ($). State Highway Safety Offices are encouraged to choose countermeasures that receive three, four, or five stars. For example, the “Pedestrian Safety” topic area includes “lower speed limits” as a countermeasure. CTW rates this countermeasure four stars for effectiveness and rates it low cost (a single “$”) because most of the cost is for changing the signs. (The connection between enforcement and changes in speed limits is complicated, and sorting out the expected contribution of each action presents a research challenge for the practitioner.58) For each topic area, CTW also identifies countermeasures that are unproven or need more research.59

As seen in the “lower speed limits” example, there is some overlap among the general guidance for road design, the crash countermeasures for road safety projects, and the countermeasures targeting road user behavior. This overlap could inspire collaboration, or it could lead to confusion and even conflict.

EDUCATING TRANSPORTATION PROFESSIONALS

The size and skills of the road safety workforce in the United States has been a concern dating to at least the mid-2000s.60 Still, formal university education in road safety continues to be weak, especially in undergraduate civil engineering programs. Practicing road safety professionals—and the agencies that employ them—rely on post undergraduate, professional, or continuing education programs, and many of these educational opportunities are essentially self-directed.

Universities, primarily through the bachelor’s degree in civil engineering, have long been the source of trained transportation professionals in the United States. In civil engineering, the traditional transportation educational content remains focused on planning, designing for, and managing capacity and level of service for motor vehicles. Some respected civil engineering programs do not include road safety at all;61 others imbed it in non-engineering topics such as planning or as part of postgraduate or specialty research

___________________

58 The CMF Clearinghouse lists CMFs for speed limit reductions, all with lower confidence levels (3 stars) and all data collected outside the United States.

59 NHTSA. 2023. Countermeasures That Work.

60 Building the Road Safety Profession in the Public Sector: Special Report 289. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2007. https://doi.org/10.17226/12019. See also Gross, F., and Jovanis, P. 2008. “Current State of Highway Safety Education: Safety Course Offerings in Engineering and Public Health.” Journal of Professional Issues in Engineering Education and Practice 134(1), pp. 49–58; and Model Curriculum for Highway Safety Core Competencies. 2010. NCHRP Report 667. https://onlinepubs.trb.org/onlinepubs/nchrp/nchrp_rpt_667.pdf.

61 For example, despite listing “safety” as a desired knowledge area for Civil Engineering graduates, none of the required classes at the University of Texas focus on safety; see https://catalog.utexas.edu/undergraduate/engineering/degrees-and-programs/bs-civil-engineering.

programs.62 To achieve and maintain ABET (formerly Accreditation Board for Engineering and Technology) accreditation, civil engineering programs at a minimum must teach to the licensure examinations. The Fundamentals of Engineering exam, the first step toward engineering licensure, only minimally addresses road safety.63 The American Society of Civil Engineers regards the M.S. degree as the First Professional Degree (FPD) for the practice of civil engineering (CE) at the professional level.64 Transportation and traffic engineers are trained at M.S. levels in many schools. However, their training does not include much emphasis on road safety.

FHWA and NHTSA have made efforts to fill the gaps in the need for professional or continuing education in roadway safety. FHWA has developed the Roadway Safety Professional Capacity Building Program, which “provides resources to help safety experts and specialists develop critical knowledge and skills within the roadway safety workforce.” It provides lists of training programs in road safety provided by others and hosts peer-to-peer and community of practice programs, where professionals share experiences and train each other on the fly.65 The training itself is provided by numerous organizations such as AASHTO, the Institute of Transportation Engineers, the American Society of Civil Engineers, the National Highway Institute, the U.S. DOT Transportation Safety Institute, and the FHWA-funded National Center for Rural Road Safety. Training may be instructor-led, online, or webinar recordings.66 NHTSA sponsors a Highway Traffic Safety Professional Certificate program through the Transportation Safety Institute. The program is designed around the needs of NHTSA personnel and grant recipients, staff in State Highway Safety Offices, and law enforcement personnel.67

Another route for getting safety research to practitioners is through the many research products published by TRB’s cooperative research programs. NCHRP released at least 13 traffic or road safety guidance publications in

___________________

62 Gross, F., and Jovanis, P. 2008. “Current State of Highway Safety Education: Safety Course Offerings in Engineering and Public Health.”