Asset Information Handover Guidelines from Planning and Construction to Operations and Maintenance (2024)

Chapter: 1 Introduction

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

Asset information handover is the process of gaining the information and data required to appropriately manage and maintain constructed assets (the built environment) throughout the intended useful life of each system, item of equipment, or component. This asset information is critical for the successful future management and maintenance of constructed assets. Knowing what you own and how to care for it impacts not only airport operations but also the “bottom line.”

For purposes of this guide, the word “asset” refers to a constructed item that is typically created as part of a design and construction project. The term “asset” can mean an entire building or the flooring within that building. Various components create an airport: airside and landside assets, vertical and horizontal construction, visible (or aboveground) assets, and buried ones such as utility piping. Each of these constructed assets is a part of the built environment at an airport.

The data associated with asset information handover business processes supports asset management within any organization. An organization needs this information to appropriately maintain and manage the newly acquired assets created by a project. Obtaining the information required to operate and maintain a constructed asset upon its completion is a little like being provided with an owner’s manual for purchases such as toys, refrigerators, and automobiles.

Most design and construction projects are developed with and supported by drawings and specifications. Historically, this process has occurred on paper. As more design and construction firms embrace newer technologies, paper is less important. There is increasing reliance on the data and software tools available to design, construction, and even owner teams. The concept of asset information handover resides within the specifications and construction documents that are a part of any contract between an owner and the construction team. Asset information handover requirements reside within the Division 01—General Requirements (Division 01) set of specifications, as part of formalized project closeout submittals.

Case Study Organizational Highlights

Several airport organizations (including large-, medium-, and small-hub airports) and one non-airport organization were identified to participate in this research project. These participants are identified in Table 1. Every one of the participating organizations utilizes asset data in some form. One might assume that airports must understand what it is they own, and what condition it is in to keep the airport operational. Malfunctioning building systems, components, and other constructed assets do not facilitate or support airport operations.

Airports exist because of constructed assets such as hangars and runways, perimeter fences, and parking lots. These constructed assets must be maintained and eventually improved for they will not stay “new” forever. How does an airport develop the asset information necessary to

Table 1. Organizations participating in case studies.

| Case Study Participant | Type of Airport(s) (Large, Medium, Small Hub/International) | 2020 Domestic and International Passengersa | Dedicated Asset Management, Asset Transition/Maintenance, Management Staff |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Houston Airport System (HAS) consisting of

—Ellington Field (Spaceport) —Houston Hobby (HOU) —George Bush Intercontinental Airport (IAH) |

IAH: Large/International HOU: Medium/International |

24,690, 225 | 3+ full-time equivalents |

| Jackson-Medgar Wiley Evers International Airport (JAN) | Small | 416,000 | 0 |

| Kansas City International Airport (MCI) | Medium/International | 4,493,669 | 2 part-time, plus outsourced |

| Salt Lake City International Airport (SLC) | Large/International | 12,559,026 | 1 full-time equivalent |

| Seattle-Tacoma International Airport (SEA) | Large/International | 20,061,507 | 5+ full-time equivalents |

| The Pennsylvania State University | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Note: N/A = not applicable

aPer ACI North American Airport Traffic Report. https://airportscouncil.org/intelligence/north-american-airport-traffic-reports/

manage constructed assets and plan for future investment requirements, and in what form does the airport need asset information? There is a saying in the industry that once you have seen one airport, you have seen one airport—meaning no two airports are the same in their construction, configuration, and organization. The captured asset information and resulting data that are managed (for data also must be managed) must be specific to an airport’s constructed assets and appropriate for the airport staff, stakeholders, and customers.

This research examined the needs of different-sized airports with different levels of staffing, right-sizing data collection for airport needs, variables due to project size, and levels of accuracy and metadata requirements considered appropriate by the respective airport staff. By understanding the level of detail necessary for the planning, design, operations, and maintenance requirements of each airport and for the assets it is required to manage, a streamlined process to collect, store, and manage the appropriate asset information via handover processes can be developed.

Asset management is not a new concept, but airports and other organizations realize inefficiencies when components of data within the organization are siloed across multiple departments or work groups. Typically, there is a maintenance component, an accounting or finance and budget component, and in many instances yet another group within an airport responsible for making capital investment decisions. Quite frequently these departments don’t consult with one another when it comes to understanding roles and responsibilities.

Staff from five airports and one non-airport organization participated in the case studies developed in this research. These case studies are included in Appendix D. Table 1 presents a high-level summary of each case study.

Guide Content and Organization

The guide is intended as a resource to support defining standardized asset information handover requirements and incorporating them into an airport’s architecture/engineering/design firm requirements. These can be in the form of design guidelines or specifications or be developed as

a standalone document that requires the design team to incorporate asset information handover requirements into design and construction projects regardless of whether the project is developed by airport personnel or a third-party architecture/engineering/design firm.

The guide has been organized to allow readers to find and focus on areas of information or interest within the guide. Guide organization is as follows:

- The Summary and Chapter 1 provide a general overview of ACRP Project 09-21, “Asset Information Handover Guidelines: From Planning and Construction to O&M,” along with a description of the purpose, background, and organization of the guide and a list of airport participants in the research process.

- Chapter 2 discusses constructed assets, including what constitutes an asset that should be managed and maintained, the concept of asset hierarchy or systems (and components thereof as assets), and ensuring data quality.

- Chapter 3 introduces the concept of asset management and the identification of stakeholders’ roles, responsibilities, and needs when it comes to taking care of an airport’s constructed assets (maintenance and management). This chapter also discusses acquiring the data during project closeout that is required to support each stakeholder via accurate asset information handover procedures. The chapter discusses construction documents as the source of asset information and how the various stakeholders play a role in the use, maintenance, and management of the constructed assets resulting from construction projects.

- Chapter 4 discusses the value of establishing an asset management policy; stakeholder engagement; and the development of processes, procedures, and internal standards documents in support of asset information handover and effective asset management practices.

- Chapter 5 provides further discussion of the value of an asset management policy in support of a successful asset information handover.

- Chapter 6 identifies challenges to a successful asset information handover process and discusses possible solutions, acknowledging that there is not an obvious quick fix or “easy button” to ensure that this requested information will be received. Very few owners have been able to ensure that such documents are received upon completion of every project.

- Chapter 7 introduces and describes the case study research process. The case studies summarize the practice of transitioning asset information from design and construction teams to the ownership team and the state of asset information handover as experienced by the participants. Detailed information on the case studies is presented in Appendix D.

- Chapter 8 examines asset information handover as a documented process, required stakeholder support, why the information is of importance to asset management and maintenance, data quality, and keeping the goal of the asset management program in mind.

- Chapter 9 guides users through the various phases of project delivery; understanding roles and asset management requirements; making more informed decisions about the built environment; and integrating software tools currently used by architecture and engineering firms and construction teams, thereby improving the quality of the information obtained during project closeout.

- Chapter 10 is a discussion of road map development because road maps can assist some users with understanding the asset information handover process and related processes.

- Chapter 11 outlines some benefits of having accurate asset data and turning such data into useful information. The chapter also discusses the return on investment of having a successful set of processes that support strategic decision-making.

- Chapter 12 is a brief conclusion.

- The appendices include a list of resources for asset information handover (Appendix A), a list of terms and abbreviations (Appendix B), sample document language (Appendix C), case study summaries (Appendix D), and building information modeling (BIM) data drop reviews (Appendix E).

Understanding Project Delivery

Airports continuously create newly constructed assets, meaning they undertake the repair, renovation, or replacement of their buildings, various building systems (e.g., roofing), or even components (e.g., carpeting). In some instances, brand-new assets are created, and older ones are decommissioned and razed to make room for whatever growth, improvement, or expansion an airport needs to undertake. This is a business process—from the determination of a need to the conception of the project to its design and construction (see Figure 1). Project delivery from a big-picture perspective includes the entire process of project planning, design, and construction as well as delivery of the assets built in the project to the asset owner. A description of this process follows:

- An airport owner has an idea for an improvement to an existing facility (asset) or a more mature plan for an entirely new asset.

- Third-party firms are typically hired for major capital investment projects—such as architecture and engineering firms, design-builders, or similar construction teams. These firms are entrusted with making the airport’s new asset a reality.

- Contracts are developed that establish and define the roles and responsibilities of all parties to the contract.

- During design, the preliminary phases of the project, documents are created that define what will be built by the constructor team.

- Constructor teams develop construction documents and provide them to the airport owner upon project completion via project closeout processes.

- Organized airport owners take the project closeout documentation and make use of this asset information handover for their asset management program.

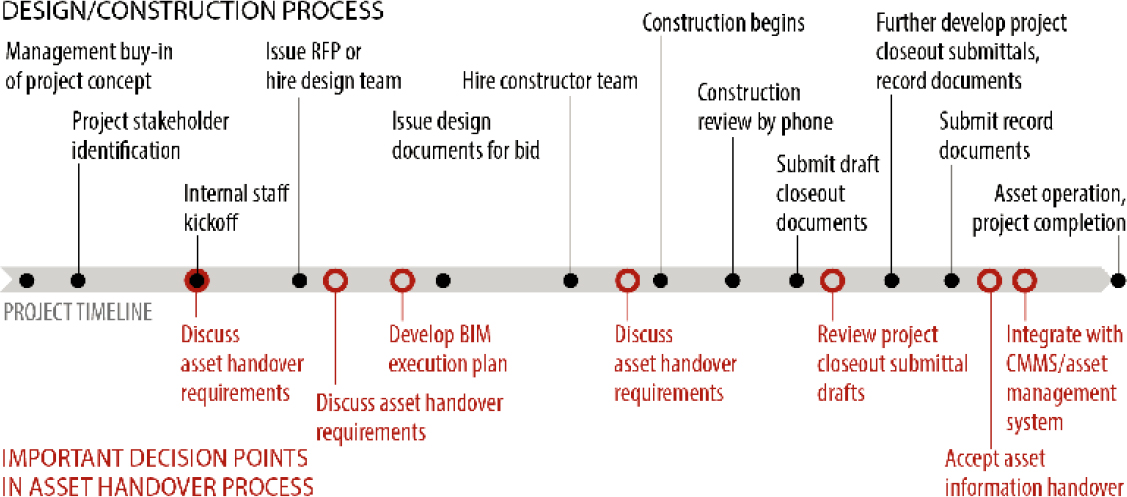

Airport stakeholders should gain an understanding of project delivery elements that affect their ability to do their jobs, especially when a job has to do with the built environment. Those airport staff members who participate in design and construction should understand not only how a project will be delivered, but also how airport maintenance and management staff will need to care for whatever asset a project creates. Figure 1 shows a timeline of a design and construction project.

Successful project delivery for an airport—for a project of any size—will depend on its stakeholders’ understanding of the design and construction process, as well as the objectives for

Figure 1. Design and construction project timeline.

operations, maintenance, and overall management of the newly created asset(s). This project delivery process should address the following:

- Ensuring that the project owner’s or sponsor’s project plan is well-defined.

- The roles and responsibilities of airport staff or third-party consulting firms who are engaged and involved from the beginning (prior to design) to ensure their respective voices are heard so they can help make appropriate decisions.

- The airport-defined design standards and contractual requirements for the design team and the constructor team; these standards and requirements should specifically outline the roles and responsibilities of each group and other participants.

- Construction documentation that is reviewed by all stakeholders at every appropriate phase of the design process. This includes everything from the drawings [e.g., computer-aided design (CAD), BIM] to specifications and alignment with any published design guidelines the airport might have and projections of cost.

- Construction activities that airport stakeholders should continuously be apprised of and approve, including design changes, product substitutions, project delays, etc.

- Project closeout activities and a procedure to ensure that the constructor team provides all requested materials.

The Magnitude of Design and Construction Information Available

The amount and variety of information types generated during any design and construction project have evolved over the past several decades, primarily because of the advancements in technology and software tools. Before the widespread use of personal cellular telephones, whenever a design team member needed technical questions answered about a given material or product, they would pick up a phone receiver on their desk and call a sales representative for the given material or product. These same manufacturer representatives would also schedule meetings with design team members to discuss new products and would provide hefty three-ring binders holding numerous illustrations of their products, technical information, color charts, and examples of how the product could be incorporated into a project.

The same type of information is available today from a hand-held device or a computer screen, with simple searches for whatever product or material a design team member is interested in learning more about. Manufacturers can now provide product specifications and other information in a format that is easy to use and incorporate into a set of specifications, and they can even provide details on how this same product should be incorporated into a project. Should a design team member have any questions or not understand such readily available information, all that is required is a simple phone call, and the needed information can easily be emailed.

Technology has made it easier to communicate with one another, and rarely do we need to wait any longer than a few minutes for an answer to a question. Within the architecture, engineering, and construction fields, advancements in technology have facilitated the generation of an enormous amount of information or data by design and construction project teams.

Managing Construction Information

Due to the advancement of software and associated tools, design and construction teams are now generating a great deal of asset-related data. This data should not simply be discarded. Airport owners, managers, and maintainers need the data; it is a valuable result of any project. The information needed to properly take care of and plan for future renewal events for newly

constructed assets is available to owners during the project closeout process and asset information handover. Owners should require the handover of information they need to operate and maintain an asset during project closeout.

Airports should understand what types of information are generated throughout design and construction of new assets as well as what will be required to maintain and manage these newly constructed assets, once they transition to the airport, as owner and operator. The available data quantities are mind-boggling, yet an airport team must understand that not all of it is necessary for future maintenance and management.

Developing a set of internal processes and procedures for asset management is integral to asset information handover. Such internal processes could range from developing design guidelines, if not actual specifications, for the airport’s preferred products and materials to specifying the requirements for project closeout—the information required during the closeout phase of any project that provides the airport with needed asset information. These processes and procedures documenting the information that airport staff requires must be considered, drafted, and ultimately put into practice. How an airport should then manage the information it receives as part of the project closeout process is of equal importance. This data and information will be needed and should be readily available and accessible to airport stakeholders. Defined processes for document management and how the information provided by design and construction teams will be stored is also critical so stakeholders will know how to find, request, and evaluate these constructed assets in the future.

To help determine the information and data attributes that are important for a specific airport, airport stakeholders should consider the following questions:

- Does your airport have in-house maintenance staff to take care of the newly constructed asset, or will you be contracting with a third-party firm?

- What is it you will need to know in the future for renewal and replacement projects (such things as quantities, model numbers, number of years on the initial warranty, manufacturers’ names, or names of local distributors, are just a few examples)?

- Is your airport planning to implement (or considering implementing) a BIM of your facilities or a digital twin?

The information or data generated in response to these questions should be documented in contracts, in the specifications, and in the project closeout document requirements.

What Kind of Information Is Generated by Design and Construction Projects?

Individuals within the disciplines of architecture and engineering document their work either with pencil and paper or with software developed specifically for the architecture and engineering professions. These individuals develop everything related to the design of places where people live or work—homes, hospitals, schools, shopping areas, the horizontal infrastructure of roadways, utility systems that support various communities, and airports.

So how do the architectural and engineering communities of practice stay in alignment with one another? These design teams use similar tools to create and define a project and quite frequently share software files to expedite the process. In turn, these electronic files are typically handed over to an owner or a constructor team to be further developed and refined during the construction phase of the project.

Many different types of files are generated, including text-based specifications and procurement/contract documents and drawings (that today are generated mostly in BIM software). The graphic

illustrations (regardless of the software used) and the written explanations supporting those graphic documents become construction documents (also referred to as contract documents) and are products of an architectural/engineering design. These products are generated to define a project, to help facilitate pricing (typically executed by the constructor or bidding team), and to be used during construction of the project.

In the United States, specifications typically align with the standards developed by the Construction Specifications Institute (CSI), which address the practice of developing specifications and construction documents. This organization has published classification systems that define what subjects (assets) should go where—MasterFormat and UniFormat. MasterFormat is typically used by specifiers to ensure that specifications sections appear in a sequence that can be easily identified by other users of the documents or the “project manual.” Basically, the classification defines what products or materials should be specified where in a specifications section and provides an organization scheme by divisions, with Division 01 representing the “general requirements” for any given project. An airport should pay attention to the language in these general requirements specification sections and even provide its design teams with input on appropriately outlining what information (data) and documents the airport, as the owner, wants to receive once the project is completed. This Division 01 section is referred to as “project closeout,” “closeout procedures,” or “closeout submittals,” depending upon the nature of the project and the level of detail that is required.

What Is Project Closeout?

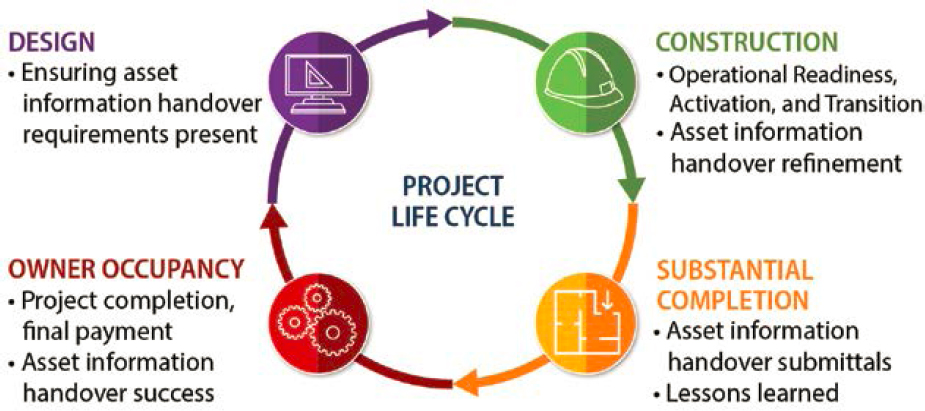

Project closeout is the process of ensuring that a design and construction project is complete and that the requested systems, products, materials, and components have been installed, have been provided as requested, and are functioning as planned. Project closeout also involves evaluating the project, learning lessons, and ensuring that requested deliverables are usable for the airport owner. Final payments to contractors are made at project closeout, and airport stakeholders are notified of asset information handover success. Figure 2 illustrates the concept and asset information development throughout the project life cycle.

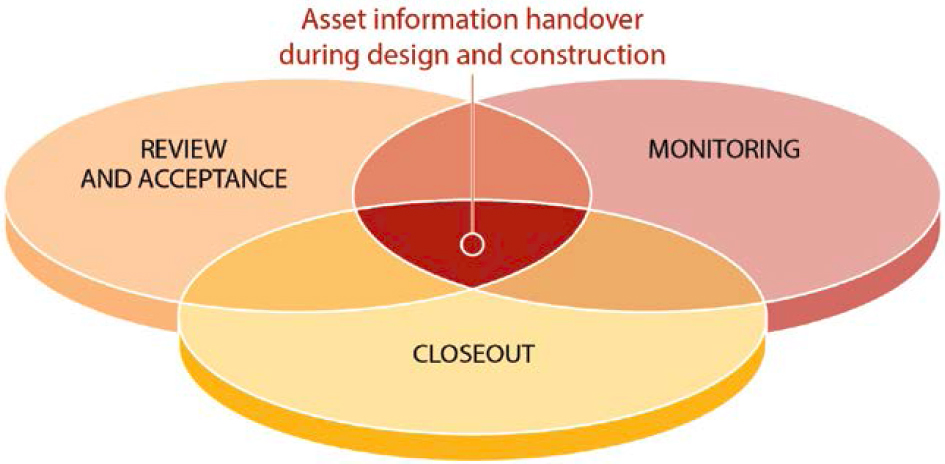

Project closeout is also the time of asset information handover. A successful project closeout process will almost guarantee a successful transition of the documents and electronic files requested by the owner and maintainer of the newly constructed assets. Successful asset information handover ensures that an airport will get this information, not only in a timely manner but in the formats required for its existing business processes. The conjoining red area within Figure 3 represents how airport staff, through continual monitoring during design and construction projects, will see the benefits of successful asset information handover.

If asset information handover as a process is not followed, airport staff will have to conduct their own research to obtain an understanding of their newly constructed assets when the construction team leaves. Quite frequently, the project closeout deliverables specified within Division 01, are provided but not categorized in a useful manner, are incomplete, not accurate, or do not fully inform airport staff about the newly constructed assets. These issues are sometimes the result of the airport not ensuring that the needed information was outlined appropriately in the Division 01 specification section addressing closeout. Simply discussing your needs or expectations for asset information handover during a project meeting, without appropriate documentation in the construction documents, will not ensure receipt of that information upon closeout and beneficial occupancy.

Electronic Operations and Document Management Libraries

Understanding project closeout or asset information handover is a first step. Airport stakeholders must know what types of information will be required by their maintenance staff to appropriately require this information in Division 01 project closeout specifications. Developing an electronic library for maintenance staff benefits an airport. If asset information handover has been successful, establishing an electronic library for maintenance staff should be relatively easy.

The asset information handover documents can have multiple forms or formats such as .jpg files for photographs, PDF files for manufacturers’ literature and asset warranties, drawings or BIM files, active files such as MS Excel or other types of spreadsheet applications, and other graphics and text files. What should an airport do with these varying types of documents and information, so that they remain useful in the future? It is important to have some kind of document management in place so that documents can be accessed when they are needed. Asset information handover is not just about obtaining accurate and complete data once a project is complete but also ensuring that the data is retrievable when airport staff needs it.

Stakeholder staff should be consulted about their asset information needs to ensure they are addressed. However, typically staff will need access to manufacturers’ literature (e.g., specifications and maintenance requirements), appropriate operating procedures (of installed equipment and components), troubleshooting guidelines, warranty information, and even safety-related requirements. To effectively utilize asset information obtained during project closeout, CAD or BIM files and acquired databases should be uploaded into software systems that are accessible to maintenance staff, or asset information should be provided as PDF files that are readable by maintenance staff.

Most computerized maintenance management systems (CMMSs) can link asset information handover documents within each asset record so that when a work order is generated for a particular asset, the applicable documents are readily available.

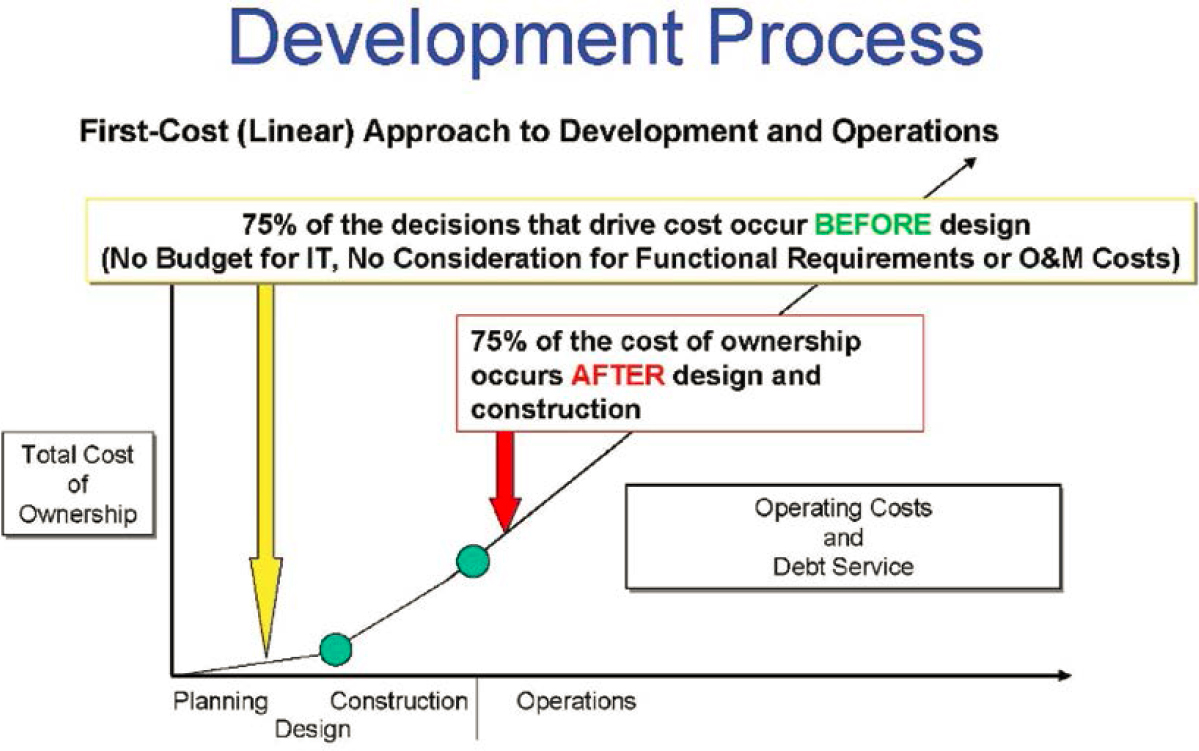

The airport benefits if decisions made during the initial phases of a project’s life cycle (the planning and design phases) are incorporated into the appropriate documents so that they are successfully transferred when a project transitions to a new phase. It has been shown that an airport’s initial design decisions represent about a quarter of the total cost of a constructed asset over its intended life. Conversely, that same asset will cost the airport three times its initial design and construction cost as diagrammed in Figure 4. The total cost of ownership (TCO) is a concept of understanding all probable costs that might occur throughout the life of an asset. Making more informed decisions during planning and design can impact TCO, potentially improving (reducing) the overall cost of an asset throughout its life.