Advancing Risk Communication with Decision-Makers for Extreme Tropical Cyclones and Other Atypical Climate Events: Proceedings of a Workshop (2024)

Chapter: 3 Risk Communication in Multi-Hazard Environments: Challenges and Learning Opportunities from Compounding Hazards and Cascading Impacts

Chapter 3

Risk Communication in Multi-Hazard Environments: Challenges and Learning Opportunities from Compounding Hazards and Cascading Impacts

Marshall Shepherd (committee member), Georgia Athletic Association Distinguished Professor of Geography and Atmospheric Sciences, University of Georgia, introduced the second session about lessons that can be learned from compounding hazards and cascading impacts. He outlined the committee’s four goals for the session: (1) gain a better understanding of how compounding and cascading hazards are defined; (2) explore the effects of recent events such as Hurricanes Harvey, Laura, and Michael on the vulnerability of infrastructure and at-risk communities; (3) characterize unique challenges associated with risk communication around these kinds of events; and (4) explore opportunities for advancing risk communication particularly around compounding hazards and cascading impacts. In a keynote talk, Jen Henderson, Assistant Professor of Geography, Texas Tech University, discussed the complicated and consequential work of classifying or defining events, particularly in the context of increasingly more frequent extreme or atypical storms. A panel followed the keynote talk and included, Jason Senkbeil, Director of Undergraduate Studies & Professor, Department of Geography, University of Alabama; Rebecca Moulton, Meteorologist, Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA); Jeff Lindner, Meteorologist, Harris County Flood Control District; and Jessica Schauer, Tropical Cyclone Program Leader, National Weather Service. The panel addressed questions about risk communication around compounding hazards and cascading impacts.

KEYNOTE SPEECH MULTI-HAZARD EXTREMES: DEFINITIONS, CLASSIFICATIONS, AND CONSEQUENCES

“Classifications and the way we talk about risk are not benign; [they have] consequences that are material,” Henderson declared, setting the stage for her keynote speech, which focused on the intersection of extreme storms and classification practices in the context of risk perception. Referencing work on organization and

categorization by Bowker and Starr (2000), Henderson contended that categories and definitions have high moral, ethical, and social stakes. Questions about how to classify extreme weather events have become more urgent as such events have become more frequent. Extremes are shaping a “new normal,” she noted, where increasingly frequent atypical and unprecedented events put pressure on traditional classification systems. “The traditional classification of natural, human-made, and hybrid disasters seems to be an insufficient tool in the face of the high complexity of the present-day world,” she explained. In thinking about the stakes of this issues, Henderson looked at both sides—first extremes and then classification itself.

Although extreme storms are generally understood in terms of “billion-dollar hazards,” a category designated by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) in 1980, this one-size-fits-all designation can exclude other meaningful ways to think about extremes, she noted. Half- or quarter-billion-dollar hazards might be considered extreme depending on the population affected and the frequency of occurrence. Storms might also be classified using intensity, death toll, and other metrics. The increasing frequency of extreme events—however they are measured—demands rethinking collective and individual understandings of the “billion-dollar hazards” category, which in turn would shift ethical frameworks and practical responses to these events, Henderson argued. She highlighted pollution as a helpful analog to extreme storms—something rare that became normal—and noted that the answers to such questions would affect risk communication itself and the types of research conducted.

Classification itself becomes an issue as hazards evolve and this “new normal” emerges, Henderson explained, and one with serious consequences. She highlighted the need for new categories as atypical storms occur more frequently and as climate change introduces new levels of uncertainty. Existing categories are also being challenged by new forms of interconnectedness; increased and different social, technical, and physical connections can create “more magnified emergencies [that] co-occur in time and space,” she noted.

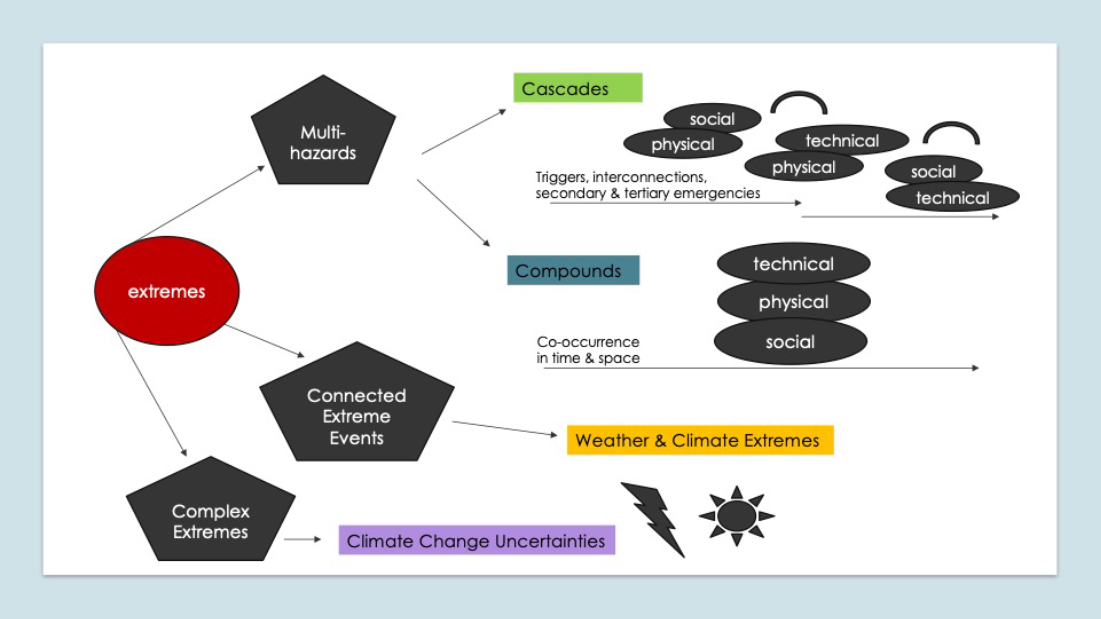

The terms “cascading” and “compounding” present particularly thorny classification challenges. One challenge lies in definitions: the term “cascading hazard” can denote both the unexpected secondary events that flow from an originating event and an event that emerges from “a series of connected errors and failures that create the conditions for a greater malfunction and more devastating consequence.” Henderson explained that the literature on compounding hazards is similar to that of cascading impacts in that it tends to repeat a general understanding of the concept as “a combination of multiple drivers and/or hazards that contribute to societal or environmental risk.” Like extremes, compounding hazards and cascading impacts are occurring more frequently to the point of being “ubiquitous,” and, thus, put pressure on traditional categorization. For example, typologies and models exist for classifying and thinking about compounding hazards and cascading impacts; however, she explained, these categories speak primarily to physical infrastructure and drivers, and often do not account for the impact on social and technical factors or their role as driving forces.

Henderson highlighted several conceptual models for thinking more expansively about cascades and compounds, such as how extreme events can produce multiple hazards that in turn result in cascades that trigger emergencies and co-occurring compounds (e.g., technical, physical, social) (Figure 3.1). The sociologist Susan Cutter, for example, developed the idea of “social cascades” to refer to “the social, cultural, economic, and political effects of consecutive disasters within either close temporal or close spatial proximity” (Cutter, 2018, p. 23), arguing that they should be included in research alongside physical drivers. One source for such models are media that take up topics not usually discussed in the research world; in this vein, Henderson flagged journalistic material, including “Floodlines,” a podcast produced by The Atlantic that traces multiple complex, intersecting elements around Hurricane Katrina, as well as work by Dave Eggers, and Kai Erikson and Lori Peek.1

According to Henderson, the consequential way that classification impacts communication can be clearly seen during multiple simultaneous events, where warnings and responses for each hazard can contradict one another. For example, in the case of TORFF events (Tornadoes and Flash Floods that happen simultaneously), warnings that deliver conflicting information to people about what they should do often overlap (i.e., come within 30 minutes of one another). Henderson noted that more than 400 such overlaps occur each year in the United States (see Nielsen et al., 2015). Tropical cyclones, which often involve multiple overlapping

SOURCE: Presentation by Jen Henderson on February 5, 2024; created by Jen Henderson.

___________________

1 More information about the “Floodlines” podcast is available at https://www.theatlantic.com/podcasts/floodlines/.

wind and water threats (e.g., synoptic winds as well as tornadoes; storm surge as well as flash flooding), have an even greater potential for overlap. Further complicating matters, overlaps can change as timing and scale of the multiple hazards evolve, she explained. Cascading hazards present similar communication challenges.

Henderson elucidated four main communication challenges around multi-hazard events involving tropical cyclones. First, as in the case of TORFFs, instructions may conflict (e.g., sheltering is different in the case of a tornado or flood). Second, the increased complexity that comes with dealing with multiple hazards and how messaging and prediction often involve multiple agencies, different spatial and temporal scales, and threats that move and evolve. A third challenge, which stems from the previous two, is that the public may have a higher risk perception for one hazard than the other, regardless of which hazard is most threatening in a given storm (see Henderson et al., 2020). News coverage and policies driving messaging from various agencies about risks for flood and tornado hazards can “unintentionally magnify one hazard” over the other instead of helping people to prioritize which hazard to understand as the most threatening. Finally, communications experts are experiencing increased stress and strain due to the more frequent and intensifying extreme events.

Classification decisions have a ripple effect with social and ethical dimensions, Henderson noted. They can, for example, determine who has an advantage and who suffers; which regions benefit more or less; and who keeps or loses jobs. Categorization decisions also shape how knowledge is built and shared. Classification underpins disciplinary knowledge that evolves around different hazards, each of which has its own “epistemic culture of risk” as well as research agendas, funding mechanisms, labs, technologies, and policies Therefore, the nature of classification systems can inhibit interdisciplinary and convergent thinking, Henderson argued. However, a lot of opportunity for expansive, cross-disciplinary thinking lies in the work around social cascades and compounds. Henderson concluded by stressing the importance of “integrative, convergent work” that looks at cascading impacts at multiple temporal and spatial scales; attends to unanticipated consequences of compounding events; and—especially—takes a holistic, flexible approach that classifications do not always allow. Such research would also “re-examine the things that classification hides or doesn’t make visible for us,” Henderson noted.

RISK COMMUNICATION AROUND COMPOUNDING HAZARDS AND CASCADING IMPACTS

In the panel that followed Henderson’s keynote speech, speakers took up different angles of a theme that resonated throughout the session as a whole: the complexity of risk communication about events with cascading and compounding hazards, especially as extreme storms occur more frequently and have unanticipated impacts.

Senkbeil began by elaborating on two themes related to cascading and compounding hazards: (1) an increase in hurricanes at the tail of distribution in recent

extreme events, for example, the number of hurricanes that have rapidly intensified within 400 kilometers of the coastline has tripled since 1980 (Li et al., 2023) and (2) the potential for social science to reveal how people understood previous hurricanes and to deepen understanding of how previous experiences impact their current perception of risk. Although every storm is unique, in multi-hazard storms, either water or wind can pose a greater threat and distinguishing between the two can help produce more effective communication, Senkbeil explained. For example, windstorms are fast-moving, with less rain and a lower surge volume but a higher peak surge, while water storms tend to be slow-moving, bringing more rain and a larger storm surge volume, he noted. Communicating “the greatest hazard of concern,” as Senkbeil called it, can help people understand risk and take appropriate action.

Another major challenge to risk communication lies in enabling the public to understand the risks posed by events that are more extreme than those previously experienced, Senkbeil noted. People often have a “benchmark storm”—a previous event against which they measure risk in the present; however, as compounding, cascading hazards increase, past experiences are not always comparable to what might happen in the “new normal,” and benchmarking can lead people to underestimate the severity of the present threat. However, Senkbeil suggested, this thinking could be leveraged by emphasizing the potential for the current event to exceed the “ceiling” of the benchmark event. It can be especially difficult to get the public to truly understand the impacts and risks of water storms, he said.

Messaging and predictability are also challenges during what Senkbeil termed grey swan events—storms that are predictable but very unlikely (“in the skinny tails of the distribution”), which often intensity rapidly within the 24-hour period before landfall. He provided two examples from Hurricane Michael, when rapid intensification meant that people experienced much stronger winds than expected and experienced impacts in new places.

Senkbeil also discussed several avenues to improve risk communications. First, communications that emphasize the hazard of greatest concern, especially distinguishing between wind and water storms, is extremely helpful. This approach could also enhance the public’s understanding of the risks posed by cascading threats that accompany each type of storm and each hazard within a multi-hazard storm. Second, the new NHC cone of uncertainty, which shows more inland impacts, is a positive step toward clearer communication about the cascading impacts of storms. Finally, communications that compare predictions for a storm in progress with the values for previous, benchmarked storms to which people often refer can help to set accurate expectations and understandings about risk.

Moulton spoke about the importance of listening to different audiences and partners to effective communication, as well as how her own experiences shaped her understanding of such work. Through her work supporting local emergency managers (EMs) and evacuation messaging, she has realized the central importance of listening to the audience, understanding their questions and problems, and talking directly with them whenever possible. Moulton shared that attentive

listening over the years prompted her to reframe her own role. Rather than focusing solely on the presentation of accurate data, she embraced an approach grounded in seeking to understand the needs of her various audiences. Now, her guiding question is “How can I see things from their perspective . . . and let their needs inform all stages of our process, from planning to the briefings operationally and during the incident response?”

An approach grounded in listening and direct engagement is especially important, Moulton noted, because an enormous amount of information is freely available to everyone. Consequently, expertise in risk communication is not solely about the delivery of accurate information. Rather, one key to effective risk communication lies in figuring out what helps people understand information: what to pay attention to, what the context might be, and how to deal with uncertainty, for example. Probabilistic products are also appearing more and more, while deterministic products are waning. This change drives the shift from delivering information to helping people understand it, Moulton explained. She noted that this approach enables meteorologists to provide context as needed, “select the right information” from all the unknowns, and help individuals better navigate a large amount of uncertainty. It also gives space for the expertise of others: the EMs and other local officials, members of the public, and other partners who best know their situations and needs.

Navigating complex storm events with multiple hazards likely involves collaboration among individuals with specific areas of expertise, including meteorologists, other scientists, EMs, and local officials and community leaders, across multiple locations and agencies. Moulton noted the importance of listening to “subject matter experts” as part of this essential collaborative work. Along with the multiple perspectives that come with subject matter expertise, she added, this approach provides room for the human element of this work, where people are in stressful situations and often dealing with multiple events at once. Moulton’s remarks captured what would emerge as a consistent theme throughout the workshop: the humanity of everyone involved in decision-making and communications during these events, including the public. Underneath all the layers of expertise, roles, and details of the specific situations, “we’re all people,” Moulton said. She concluded with an anecdote from her own life, recalling a moment when, while working for the White House Interagency Working Group on Extreme Heat, her own air conditioning broke. In that moment, she said, her perspective slipped from the outside expert to “one of the people.”

Jeff Lindner spoke about risk communication particularly related to Hurricane Harvey. He, too, emphasized the complexity of risk messaging around a multi-hazard event, especially one that impacts a large geographical area. For Hurricane Harvey, this situation meant that the forecast for the mid-coast of Texas was a category 4 impact, with heavy winds and storm surge, but the forecast for the upper coast, including Houston, was for flooding from inland freshwater rainfall. Interpersonal communication across geographical regions can further complicate messaging about multiple hazards and appropriate actions to take. For example,

Lindner explained, people in the northern part of Harris County may hear that friends and family in coastal areas are being told to evacuate because of the storm surge, and wonder whether they too should evacuate, although their area is threatened not by a storm surge but by rainfall flooding (which usually does not trigger an evacuation in Houston or Harris County). He reported that in areas that do require evacuation, evacuation zones were mapped onto ZIP codes, so that most people knew their situation.

Linder shared two major challenges to risk communication: (1) helping people to understand the forecast information conveyed by various products and (2) helping people to understand the potential impacts of forecasted events. Although his comments focused on misunderstandings and mis-readings of messaging in relation to Hurricane Harvey, he noted that such challenges are not unique to that event and that lessons learned are applicable to many different instances and products. Lindner used a graphic produced by the National Weather Service (NWS) that predicted rainfall and catastrophic flooding in the Houston area during Hurricane Harvey to highlight a common misreading that underpins misperceptions of risk (Figure 3.2). People tend to believe that if they are not in the “bullseye” (i.e., the maximum amount of rainfall), then they will be fine: “I’m only going to get a foot of rain; the rainfall is spread over five days, so even 35 inches isn’t so bad.” Lindner stated that the rainfall rate is a salient issue with tropical systems and flooding. He noted that risk communications about rain for Hurricane Harvey may not have clarified the fact that rainfall would not occur at a steady rate over time, but in intense bursts that would result in “10, 15, 20 inches in a 12-hour period.” Also, during Hurricane Harvey, members of the public focused on the fact that the hurricane itself would likely hit another area and did not understand that they might be impacted by far-reaching effects.

SOURCE: Presented by Jeff Lindner on February 5, 2024; created by National Weather Service.

Model forecasts—particularly those showing extreme scenarios—can also challenge clear communication and risk perception, Lindner noted. These models are often deterministic in nature and therefore differ from the official forecast, which foregrounds probabilistic information; and they are sometimes included in media broadcasts and reach the general public. Further, Lindner noted, such deterministic models can also influence decision-makers in the emergency management community, who would ideally rely on the official forecast.

Lindner echoed Senkbeil’s comments on benchmarked storms: people understand risk of current/forecasted events through the lens of their experiences of prior events and assume that no storm will be as bad or worse as their benchmark storm. This assumption become especially problematic with multi-hazard storms because people do not anticipate extensive storm surge flooding, as evidenced, for example, in responses to Hurricanes Katrina, Ian, and Charley: “I just could never believe the water would get this high.” Benchmarking contributes to a dangerous lack of understanding around risk in the case of rare or extreme events for which there is no historical context, Lindner said. Meteorologists can see “outlandish forecasts” (e.g., 50 inches of rain) that do not accord with previous experiences, and which people—whether the public or EMs—doubt or use valuable response time to verify. In these cases, different sources must be on the same page and distribute the same information to build confidence in the forecast.

A related challenge introduced by extreme, multi-hazard events is the pressure they can put on meteorologists to discern the line between forecast and impact, which can cross into areas that lie beyond their expertise, Lindner explained. “Our job is to forecast [and] to explain those forecasts, but . . . we don’t have all of the knowledge for all of the impacts that can happen in a certain situation.” It is not always clear whose job it is (e.g., forecasters, local officials, EMs) to know about and communicate about all possible impacts. Contradictory call-to-action statements, discussed by Henderson and Senkbeil, also confounded risk communication during Hurricane Harvey, Lindner noted. That storm affected a large geographical area, and thus products seemed to contradict one another because they addressed different impacts at different locations. Different hazards also affected the same area, leading to conflicting instructions: tornadoes prompted calls to retreat to the lowest floor of the house, while flash flood warnings had people going onto their roofs. In this situation, Lindner said, the Emergency Operations Center (EOC) and local NWS Office decided to keep the focus on flooding as the primary threat because the tornadoes were short lived and weak. Relaying the risk of a tornado often seems to take precedence over relaying the risk of flooding in people’s minds, Lindner explained, so it was important to take steps to keep the flooding risk at the forefront. In summing up, Lindner emphasized the importance of discerning: “What is the primary threat right now?” Not every event is the same, so each requires discernment of the primary threat and then creation of appropriate messaging— “putting it out there, and keeping it out there, and making sure that hopefully what you’re asking people to do matches what the highest threat is.”

Jessica Schauer rounded out the panel with a discussion of how risk communication originates—that is, how different agencies and platforms coordinate and amplify key messages—and how to ensure consistency downstream. “Every storm is different,” Schauer noted, a sentiment that resonated with her fellow panelists’ emphasis on case-by-case decision-making and attention to local knowledge. These differences highlight the importance of close and nimble coordination around messaging as events unfold. At the NWS, a decision support services coordinator will work within the agency with forecast offices, river forecast centers, and the National Water Center, among others, to ensure that products include the NWS’s key messages and are consistent.2

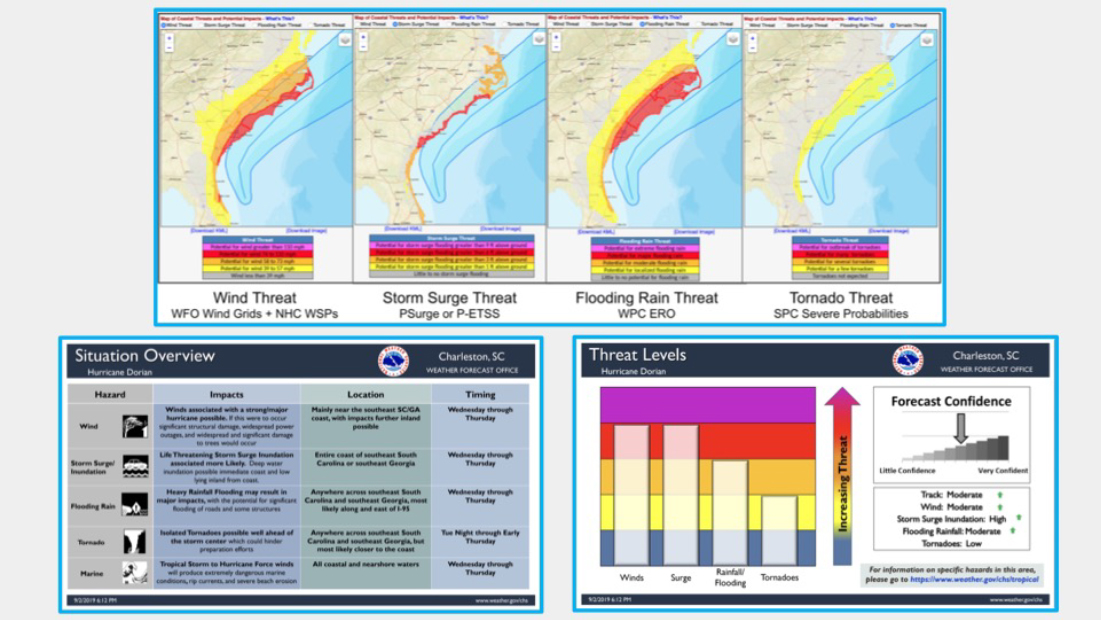

Schauer shared a series of standard graphics that are distributed whenever there is a tropical cyclone watch or warning within the Continental United States, Hawaii, or Puerto Rico/U.S. Virgin Islands. Built on probabilistic information, these graphics show “a reasonable worst-case scenario for each of the four hazards” (Figure 3.3) for a tropical cyclone. They are intended to be used by EMs, other partners, and the public to decide how best to prepare for the storm.

Using these graphics, Schauer illustrated three important aspects about the creation and coordination of risk communication, all of which served as touchstones throughout the workshop: (1) the desire for probabilistic rather than deterministic information—and the challenge around helping the public to accurately understand products that discuss risk in probabilistic ways, (2) the desire for localized information, and (3) the challenge of issuing potentially conflicting calls to action

SOURCE: Presented by Jessica Schauer on February 5, 2024; created by National Weather Service.

___________________

2 More information about the National Water Center is available at https://water.noaa.gov/about/nwc.

for multiple simultaneous hazards (i.e., going to the lowest level of a house to prepare for a hurricane versus going to a higher level of a house to escape flooding).3

The public and relevant user groups (e.g., EMs) had requested more localized information and graphics such as those presented in Figure 3.4, Schauer explained. These graphics are issued by local weather forecast offices with clickable interfaces so that users can zoom in to local levels. They also provide information on which hazard poses the highest threat to a particular area. In the case of multiple co-located hazards, social science research could help discern how best to rectify conflicting calls to action. Information about direct and indirect fatalities in past events might be used to create more tailored messaging in the future, she added.

Comparing Hurricanes Laura, Michael, and Harvey, Schauer noted that, although all were multi-hazard and rapid intensifiers, each involved different hazards that posed threats not only during the active storm but also in its aftermath. For Harvey, flooding often prevented medical access in the wake of a tornado. For Michael, the large impact area complicated recovery after the storm. For Laura, widespread power outages meant that many people struggled to power their homes while those with generators risked carbon monoxide poisoning. Attending to post-event messaging is critical too: “The event isn’t really over when the weather part of it is over.”

The question-and-answer portion of the panel opened with a question from

SOURCE: Presented by Jessica Schauer on February 5, 2024; created by National Weather Service.

___________________

3 More information and graphics about hurricane threats and impacts is available at https://www.weather.gov/media/srh/tropical/HTI_Explanation.pdf.

Sunny Wescott, Chief Meteorologist, U.S. Department of Homeland Security, who shared that one of the largest challenges in her work has been communicating extreme impacts within the current classification system. For example, a tropical storm with atypical hazards is dismissed as being “just a tropical storm, so I’m not going to stand up an EOC.” She also noted that traditional metrics may miss the atypical features of an extreme storm. Wescott asked whether agencies are considering changing the categories themselves, and how storms are classified, in addition to or instead of changing perception of the categories. Senkbeil responded that the National Hurricane Center (NHC) is ultimately in charge of classification decisions and determining whether such changes would yield more accurate perceptions of risk and improve responses. Senkbeil added that the one-to-five scale category is a useful but very simple product and that Schauer’s graphics are another successful, but more complex, way to quickly communicate the different hazards and uncertainty. Calling for products that find the middle ground, Senkbeil noted that most people spend about 20 seconds getting information. Moulton responded, saying that Wescott helpfully foregrounded the idea that people tend to miss impacts from “background level” hazards that do not fit or meet the criteria of in-place classification systems. She mentioned the Waffle House Index—based on the restaurant’s reputation that it remains open in all but the very worst storms—as an informal measure that is quite effective at helping people to understand the challenges they are facing.

Regarding the concept of cascading or compounding effects, Castle Williamsberg, Social Science Research-to-Applications (R2X) Coordinator, NOAA, noted that “it’s crucial to also evaluate the effects of our risk communication messaging across our information ecosystem” and raised the question of how best to evaluate these communication consequences. For example, Lindner noted the cascading impacts of a loss of power, which can result in loss of communications channels, emergency services, and back-up power. The question of whether forecasters discuss impacts, particularly cascading impacts, is particularly important, he said, because people’s perceptions about the accuracy of the forecast are sometimes based on their prior experience of impacts.

HIGH-LEVEL SUMMARY OF SESSIONS ONE AND TWO

Andrea Schumacher, Ann Bostrom, and Hugh Walpole, Associate Program Officer, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, provided a high-level summary of the first two sessions. Many of the takeaways wove throughout the workshop, including the central importance of strong partnerships, the usefulness of localized information alongside general forecasts, the challenges inherent in communicating about complexity and uncertainty, and the importance of listening to target audiences.

A major challenge to risk communication is the noise that is produced by a glut of information that does not help individuals understand what they might expect and how they might prepare (i.e., historical facts, general data about category or

intensity of a tropical cyclone). Schumacher explained that in this context, noise can be described as statements and graphical information “that don’t necessarily relate to locally experienced impacts.” This challenge dovetailed with another common theme, that is, whether and how “impersonal graphics [i.e., not tailored to any specific community] convey personal risk.”

Bostrom noted a similar theme in “all events are local,” in terms of both localized information sent as part of the messaging and local data about actions taken by individuals in response to that information and their own experiences, gathered through social observational research. Understanding both the specific local impacts of a given hazard (which is often one of several hazards) and the bigger picture of how a multi-hazard storm evolves and moves is important. Such an understanding involves tracking the dynamic nature of the storm, as well as the speed and location of impacts of multiple hazards happening at the same time. This need for agility in storm tracking has a counterpart in the need for agile, on-the-ground research before and during the event, supported by a strong research infrastructure. Tracking what people experience, and how they act in response, can deepen understanding of how they will respond in the future, which ties into the concept of benchmark storms.

As storms are becoming more complex, communication tools are becoming more sophisticated, and this trend. Bostrom linked this theme to two important topics from the sessions. First, more research is needed on how information moves across various platforms (within both the public and private sectors) and on how to leverage artificial intelligence (AI) tools to communicate more effectively. Second, and relatedly, in the face of evolving climate change and in “the context of a new normal of increasing extremes” the need to be nimble and consistent is even more pressing. This need can be met through strong partnerships with good information flow between partners, especially in the face of extreme or unprecedented storms. A “strong coordinated community” is critical to consistency in messaging that goes beyond “traditional” messaging.

Finally, Walpole noted a persistent issue that centers on categorizing a compounding or cascading disaster. Categorization decisions include how to communicate about complexity and uncertainty and which hazard to focus on in a multi-hazard context. Therefore, Walpole noted, panelists grappled with the ethical dimensions of these decisions, including who decides the details and who creates the messaging.

SUMMARY OF BREAKOUT DISCUSSIONS: APPLYING RISK COMMUNICATION LESSONS FROM OTHER HAZARDS TO THE TROPICAL CYCLONE CONTEXT

Breakout discussions about applying risk communication lessons from other hazards—earthquakes, extreme heat, flooding—to the tropical cyclone context followed the keynote and panel discussion. Jeanette Sutton (committee member), Associate Professor, College of Emergency Preparedness, Homeland Security and

Cybersecurity, University at Albany, State University of New York (SUNY), introduced this portion of the workshop. She explained that the main objectives for this session were to mine past risk communication experiences for insights into future endeavors, and to discuss how the scope of research around tropical cyclone risk communication might be expanded.

Earthquakes

Richard Allen, Director, Seismology Lab, University of California, Berkeley, shared the takeaways from the breakout discussion on earthquakes. He began by stating that earthquake early warning efforts in the United States are relatively recent and successful. The U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) is the agency responsible for issuing the alerts that are part of the early warning system, from monitoring and reporting on earthquake activity to warning people. With this system now in place, the opportunity exists to evaluate the effectiveness of message delivery—how to make messages more impactful, how to reach more people, and how to support more effective action. The evaluation should consider the roles of different channels (e.g., Wireless Emergency Alerts [WEA], Android apps) and of the speed of onset. A 10-second warning, for example, does not allow for either elaborate messaging or action. There is “an interesting tradeoff between the . . . lack of warning time and the simplicity of the message.” A simple message may help more people take more effective action, Allen explained. He commented that including maps in messages is not effective because understanding them takes more time than people usually have. Very short warning times necessitate education and preparedness before the event to help people know how best to understand messages and take immediate action. A third aspect of effective communication is the use of clear, understandable language and concepts; Allen highlighted the term “intensity,” which is of critical importance to the warning community, such as forecasters, but largely misunderstood by (or unknown to) the public.

Extreme Heat

Micki Olson, Senior Risk Communication Researcher and Project Manager, Emergency and Risk Communication Message Testing Lab, University at Albany, shared the takeaways from the breakout discussion on extreme heart. She commented that extreme heat has no standard definition, which can lead to inconsistent messaging across local and state-wide agencies (e.g., how watches and warnings are issued). At the same time, extreme heat affects millions of people and has a “public health component that we don’t usually see with other hazards.” Research has shown that equity and the vulnerability of different populations make how risk is communicated especially important: demographics and, to a lesser extent, location have been shown to affect individuals’ risk perceptions and the extent to which they are able to heed heat warnings and take appropriate action. Jargon,

technical language, one-way communication from expert to public, and assumptions about what leads to behavior change all inhibit people’s understanding of how extreme heat might affect them. However, most people do understand that they are vulnerable and “generally understand the benefits of what they’re supposed to do to protect themselves.”

Further, experts do not usually understand how their messaging is received by the public. People might not understand the specific differences between, for example, a tropical storm, tropical depression, hurricane, or tropical cyclone. Olson highlighted the group’s focus on plain language, localized messaging, and consistent messaging as critical for effective communication, along with increased attention to the public health dimension of extreme heat.

Flooding

Amanda Schroeder, Senior Service Hydrologist, National Weather Service, reported on the third group’s discussion about flooding. Coordination between the private and public sectors, as well as the need for stronger cross-sector relationships, especially between academia and government agencies, was a focus of that discussion. One example of coordination is flood inundation mapping by the NWS and nongovernmental entities, such as Flood Vision, a private-sector tool by Climate Central.4 Schroeder noted that different sectors often want different information, with different needs (including the role that timing plays in communications practices) and different content (e.g., messages that contain model-based, deterministic information versus probabilistic information). Discussants also raised the idea that the government is “often not at the forefront of technology advances,” a standing that might be improved through better partnerships.

___________________

4 More information about Flood Vision is available at https://www.climatecentral.org/floodvision.