Advancing Risk Communication with Decision-Makers for Extreme Tropical Cyclones and Other Atypical Climate Events: Proceedings of a Workshop (2024)

Chapter: 7 New Approaches to Unmet Needs: Communication for the Whole Community

Chapter 7

New Approaches to Unmet Needs: Communication for the Whole Community

Clear communication rests on attention to both the crafting of the message and the needs of the target audience, a theme that was evident throughout the afternoon session of the second day, which included a keynote address by Wändi Bruine de Bruin, Provost Professor of Public Policy, Psychology, and Behavioral Science, University of Southern California, two panels, and a demonstration discussion of a prototype product. Ann Bostrom, moderator, listed the goals of the session, which were discussing “current and emerging strategies, barriers, and challenges for communicating uncertainty and probabilistic information,” highlighting “unmet needs in communities at risk from tropical cyclones,” and illuminating “potential solutions to meet those needs in the context of communication.”

KEYNOTE SPEECH: JARGON, TECHNICAL LANGUAGE, AND PLAIN LANGUAGE

Bruine de Bruin gave the day’s keynote speech, on what Bostrom, in her introduction, summed up as the question of “how to be clear.” In her talk, Bruine de Bruin stressed the important role of clear, accessible language in effective emergency messaging. While experts often spend a lot of energy ensuring that a message is correct and accurate, “message wording is often an afterthought.” They tend to use complex language that is useful for communicating with other experts in their field but is not always accessible to the general public. Complex messages can be difficult to understand and off-putting, Bruine de Bruin explained. Therefore, “they may not work” and “they can put people’s lives at risk.”

Bruine de Bruin outlined a design process aimed at producing more effective messages. She illustrated the problems with technical or overly complex language that appears in such communications, and then described ways that experts who generate these messages might simplify their language in order to improve communication.

Social science research has illuminated approaches to making public messaging more effective, Bruine de Bruin said. Designing messages in advance of a crisis can help improve clarity and increase confidence in their effectiveness. She outlined four steps that comprise an effective design process. First, clearly identify recommendations. Second, explore why people may not follow those recommendations, perhaps by interviewing or surveying the target audience. Third, design a message based on the findings of that research to address the reasons why people do not follow the recommendations. Finally, test whether the message improves individuals’ understanding of risk and inclination to protect themselves.

To illustrate the challenges that experts face when creating clear and jargon-free messaging, Bruine de Bruin described a project on climate change communication on which her team participated with the United Nations Foundation and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), a group of climate science experts who create reports and other types of messages to be shared with policymakers, practitioners, and the general public. When the IPCC scientists were asked to identify the terms that would be central to climate change communications, two words stood out: mitigation and adaptation. These terms are central to behavior change, Bruine de Bruin noted: mitigation, as used by the scientists, refers to “the things that you can do to reduce your impact on climate change.” Adaptation refers to “the things you can do to protect yourself against the climate change that is already happening.”

Her team then conducted interviews with members of the general public, asking them to rank how easy the terms were to understand on a scale of one to five, and whether they could define the terms in their own words. The results of these interviews showed that “mitigation” was perceived as not easy to understand and that people often struggled to define it in their own words—sometimes confusing it with other words. “Adaptation” was rated relatively easy to understand, “but just because people think a term is easy to understand doesn’t mean they define that term in the same way that the experts do.” Definitions of the term “adaptation” given by interviewees centered on another meaning of that term: turning a book into a movie. Interviewees were then given the technical definition of the words and asked to suggest simple wording; their suggestions, Bruine de Bruin said, confirmed that it is truly possible to talk about these complex ideas in accessible ways. She then summarized the suggestions: mitigation became “actions we take to stop climate change from getting worse,” while adaptation became “actions we take to protect against climate change.” Terms used in risk communication about cyclones may also cause confusion among public audiences, Bruine de Bruin noted. Although the terms have not been systematically tested, she provided anecdotal evidence that people may find “shelter in place,” “storm surge,” “cone of uncertainty,” and “watch/warning” confusing. Confusion around these terms can potentially distract from recommendations about actions one can take to protect oneself.

Simplifying language is important and possible. Bruine de Bruin outlined several suggestions drawn from research on effective risk communication. The first is that messages are written for a seventh-grade reading level or lower; the

Flesch-Kincaid readability test is one such measure. Writing in simple language also involves avoiding jargon, using short words—one-to-two syllable words common in everyday language—and short sentences. Feedback from the target audience is also important in determining whether the message effectively facilitated understanding and prompted behavior change. Bruine de Bruin concluded by noting that social scientists can work alongside tropical cyclone experts in gathering data about the effectiveness of messaging through surveys, interviews, and randomized experiments.

The discussion that followed began with a conversation about why jargon is used in messaging. Micki Olson, Senior Risk Communication Researcher and Project Manager, Emergency and Risk Communication Message Testing Laboratory, SUNY University at Albany, speculated that it might be a marker of credibility or expertise—and thus, a signal that their words should be heeded. Bruine de Bruin noted that some experts also resist using simple language because they worry about losing nuance or precision. However, she continued, if the goal of communicating is to “improve understanding in a particular community, you need to use the words of that community.” She has found that when experts read excerpts from interviews with the target audience, they see more readily why and how confusion around complex, technical language arises. Bostrom wondered whether a tension ever existed in audiences composed of experts and members of the public—particularly where experts perceive technical language as having better precision. Bruine de Bruin responded that even for audiences of highly educated people, research shows that using clear, simple language still tends to work best. “It’s only when you communicate with your own expert community that it may be important to use that complex language.” She added, “If using precise terms is absolutely necessary, also describe the meaning in clear, everyday language so as to be as clear as possible.”

COMMUNICATING UNCERTAINTY AND PROBABILISTIC INFORMATION ABOUT TROPICAL CYCLONE TRACKS, TIMING, AND SEVERITY

The panel that followed took up many of the same concerns and concepts introduced by Bruine de Bruin in her keynote speech: representing the complexity of information in a way that is simple for the intended audience to understand accurately. Lace Padilla, Assistant Professor, Khoury College of Computer Sciences, Northeastern University, spoke first, presenting research on hurricane visualizations, particularly on the different biases people have around understanding graphics that represent intensity, trajectory, and size of the storm. Padilla reported on a recent study in which her team compared respondents’ biases and understanding of one such graphic, the cone of uncertainty, to an “ensemble technique” generated by utilizing the same underlying forecast model that created the cone of uncertainty graphic, making small perturbations to the model, and then sampling from the perturbation space. Each one of those lines represents one of those samples (Figure

7.1). The team first showed respondents a cone of uncertainty and asked them to use a rating scale to estimate how much damage that a specific location—a hypothetical off-shore oil rig—would incur. The ensemble technique graphics are based on the same forecast model that underpins the cone of uncertainty but are made by making small perturbations to the model; that is, samples are taken from this perturbation space and represented with individual lines that, together on the map, “show the distribution of the possible trajectories very intuitively.” Lines clustered together indicate where the storm is more likely to pass, while areas with fewer lines or no lines—even within the cone of uncertainty—show where the storm is less likely to pass. This often looks “a little bit like a normal distribution” with some standard deviation. This ensemble technique can be used to show different points of time within the forecast, Padilla noted.

The results of this comparison showed two significant differences between the cone of uncertainty and the ensemble technique. First, Padilla reported, respondents tended to read the cone of uncertainty as a “danger zone,” estimating high levels of damage inside the cone and much lower levels outside of the zone. This misconception was joined by a second: that a smaller cone of uncertainty means less damage. The ensemble technique, on the other hand, seemed to help

SOURCE: Presentation by Lace Padilla on February 6, 2024; created by Ruginski et al. (2016). Reprinted by permission of Taylor & Francis Ltd.

respondents intuit a distribution based in probabilistic data and estimate damage levels with a more gradual decline across the space.

Padilla noted two key themes around understanding drawn from these findings: “intervals create conceptual categories” and “convention misalignments cause errors.” In the case of the first theme, she explained that people tend to read lines or other spatial designations in graphics as meaningful delineations of important categories; here, respondents read the edges of the cone of uncertainty as stronger, more meaningful delineation than they really are. “The location of the exact boundary, set by the visualization designer” that delineates the cone of uncertainty is not as inherently meaningful as other, similar graphical delineations, she noted. The two sides of that boundary (inside and outside the cone) are not sharply different in terms of potential damage, although the public reads them as such.

The second theme is more general: cone of uncertainty graphics follow different rules than conventional maps. Specifically, the cone of uncertainty is an area designated by visualization designers and does not directly correspond to geographical distance the way most cartographic images do. “Pixel distance of that cone does not mean distance on a map; it means increased uncertainty.” People tend to associate the size of the cone with the geographical size of the storm, read the image as such, and consequently, plan as such. This tendency is “very, very hard to override,” even when people do know that the cone indicates level of uncertainty. Different displays can exacerbate this tendency if they show what should be smooth gradients as bands, which are often mistakenly read as categories, noted Padilla.

The ensemble technique disambiguates various parts of a storm that people assume are part of the cone of uncertainty visualization, said Padilla. It incorporates the path, showed with the various lines as described above. Uncertainty is represented with color, and size with a circle overlaying the image. This technique is an attempt to communicate clearly about all the elements that people often attribute to the cone of uncertainty.

Jessica Hullman, Ginni Rometty Associate Professor of Computer Science, Northwestern University, spoke next about the challenges to making probabilistic information accessible to the public and offered some strategies for increasing effective communication in that quarter. She began by noting that simply communicating uncertainty is not enough to guarantee that such information will be used appropriately by end-users. However, probabilistic language often leads to high levels of variance in terms of audience and interpretation, while graphics such as the cone of uncertainty often lead to biases such as those that underpin the categorical errors described by Padilla. “It’s not that there are no good ways of representing uncertainty,” Hullman noted; rather, probability itself is part of the challenge. People struggle to understand such an abstract, hypothetical way of presenting information, and often (mis)read probabilistic information as deterministic.

The first error Hullman mentioned is “deterministic construal errors,” wherein people misread visual representations of probability as representation of various deterministic attributes of the storm (i.e., size, location). “As-if optimization” is a

second type of error, wherein people suppress uncertainty in favor of a simple answer, whether that is a single location, a specific number, or otherwise. One expression of as-if optimization is rounding: for example, a person hears that there is a 22 percent likelihood of flooding in their area, and they assume that, because it is below 50 percent, they will be safe. Another example of as-if optimization is a fixation on the mean; even the most nuanced visualizations of distribution, including frequency formats, usually make visible what the central tendency is, and readers tend to focus on that information and use it to suppress uncertainty.

Uncertainty suppression is very difficult to avoid, Hullman noted. Her research shows that it is more likely to happen when people are under stress, dealing with a lot of information, and looking for a simple answer. Representing probabilistic information in ways that resist uncertainty suppression is complicated, she noted. “No matter how hard you try to design something that will force people to internalize uncertainty, it can be incredibly hard, because these tendencies to suppress uncertainty are so pervasive.”

Hullman then outlined several successful strategies for making probability visible while resisting bias and variance (e.g., audience, interpretation) as much as possible. In general, these strategies involve making uncertainty visible. One approach presents draws from the distribution one wishes to show over time, rather than summarizing the information in a single, static graphic. This approach can often help people to interpret this information more intuitively. For example, hypothetical outcome plots refer to the use of probabilistic animation, “taking draws from the joint distribution we want to display and visualizing these frames as an animation” and making it more difficult to fixate on a single central number and easier to intuit information about probability. Hullman then showed an example of a quantile dotplot, a static “frequency-based representation of probability distribution function,” and noted that giving people “this metaphor that probability is actually just the frequency” can improve their reasoning and decision-making. Although this approach offers real benefits to describing probabilistic information in terms of frequency, it can also backfire, Hullman noted. In one study, she investigated probability represented on various plots and found that even when participants did not have specific numbers (e.g., means), they had the same interpretations as if they had, because they were using the visual distance of the various data points to derive a deterministic reading and ignore the uncertainty.

A third approach to helping readers intuit uncertainty uses multiple maps and visualizations of several scenarios with simple language that explains their relationship, such as a narrative that helps readers understand that all of these scenarios could happen. This narrative approach might also include visualizations of scenarios that are highly likely, those that would be a little bit surprising, or those that are not very likely but would be catastrophic if they do occur. This approach involves determining how much visual emphasis to put on each scenario, and experimenting with readers to understand how much probability they would assign based on visualization conventions.

The discussion that followed built on the panelists’ comments, starting a question from Cassandra Shivers-Williams, Social Science Deputy Program Manager, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Weather Program Office, about strategies to change or redirect common heuristics that often underpin uncertainty suppression. Hullman emphasized that frequency framing does work well, which involves showing multiple scenarios or multiple “draws” from the same probability distribution separately. These visuals can be animated or shown as a set of static images that represent multiple possibilities. With such approaches, people are not asked to interpret the size of an outlined area as probability, which can be very difficult for them to do. Padilla added that training people to read visual information differently is very difficult; therefore, if the goal is to change responses, then annotating a familiar image will not work—the visual information itself would have to be changed.

Ann Bostrom and Andrea Schumacher noted the importance of making and testing prototypes as part of the process of developing graphics that communicate uncertainty. They presented Hullman and Padilla with a prototype demonstration of an early-phase product that was developed by atmospheric scientists for research purposes and not for official use in risk communication. Schumacher explained that this exercise, in which Hullman and Padilla commented on the prototype, is part of an effort to bring social science into the design process earlier, rather than applying social science to a product that has already undergone years of development and is near completion. The prototype product is meant to express “the maximum wind speed exceedance values for the next 5 days” in the event of a hypothetical hurricane. It consists of two graphics: one that represents the wind speeds that are most likely and another that represents a “reasonable worst-case scenario” (Figure 7.2).

SOURCE: Presented and created by Andrea Schumacher on February 6, 2024.

Padilla responded that the general public would likely focus on the visuals and ignore the textual annotations, or perhaps not understand them. Thus, people will likely come away with the misconception that the graphic is showing the track of the hurricane rather than estimates about wind speed. She also noted the likelihood of a categorical misperception, wherein people would interpret the brighter color as denoting where wind will most affect people— “Well, if I’m not there, then maybe I’m okay”—rather than probabilistic information. Schumacher explained that the graphic shows the impact area, but that, even so, it is helpful to understand that this information might be misconstrued as a cone of uncertainty, given the prevalence of that image.

Padilla noted the difficulty in communicating wind force speeds in a way that an individual can understand in a personal way. “It could be useful to remap the categories to people’s individual experiences” to help them to better understand the potential impacts for them and choose appropriate responses. Such an approach might, for example, use colors to indicate low risk (i.e., speeds that affect unstable structures) versus high risk (i.e., speeds that affect all structures).

Hullman added that readers will likely place too much weight on the boundaries drawn to delineate areas in which these specific scenarios might play out: “Are you in the hurricane force wind or not? It’s not exactly this line.” With the current prototype, she explained, people would likely place equal weight on the two scenarios rather than reading them as two probabilistic outcomes. Indicating uncertainty remains critically important and might be communicated by showing people several scenarios that are highly likely and narrate these as such. Schumacher concluded the session by noting that this dialogue highlights the importance of co-development.

EXAMPLES OF ACCESS AND FUNCTIONAL NEEDS

The session’s final panel featured presentations on reaching two specific audiences. Joseph Trujillo Falcón, Graduate Research Assistant, Cooperative Institute for Severe and High-Impact Weather Research and Operations, NOAA, & Bilingual Meteorologist, MyRadar, presented on communicating about emergencies in other languages than English, and Sherman Gillums, Jr., Director, Office of Disability Integration & Coordination, FEMA., presented on communicating with people with disabilities and other access and functional needs.

The stakes of communicating to multilingual populations are very high: the NWS has linked language inequity to fatalities since the 1970s, Trujillo Falcón asserted. With 69 million people in the United States who speak a language other than English, the stakes are only becoming higher: “it’s not a matter of if, but when this becomes more consequential in our emergency communication systems” in the future. The monolingual emergency communication system—still in place today—is a barrier for many in the immigrant and multilingual populations and can limit understanding and effective decision-making. Trujillo Falcón recounted what inspires his work now: his experience as the only Spanish-speaking meteorologist

at a radio station in a small town in Texas during Hurricane Harvey, which hit 2 weeks into his job. Witnessing the impacts of language vulnerabilities firsthand—including confusion of listeners who did not understand weather-related English information and instructions—allowed Trujillo Falcón to observe how people engage differently with information when it is in their dominant language, he explained.

“Language inaccessibility” is thus a challenge for non-English speakers in the United States, Trujillo Falcón noted. Making information more accessible brings its own challenges. Translation of specific terms can be difficult when there is no official standard definition of the term in English (Trujillo-Falcón et al., 2021, 2022). Another challenge lies in regional variations and cultural differences in Spanish that can skew meaning, he explained. For example, in Puerto Rican Spanish, “resaca” means “rip current,” but in other parts of Latin America, “resaca” means “hangover;” so educational materials released by NOAA did not communicate the same thing in all places. Various agencies’ inability to communicate consistently in Spanish for the variety of Spanish-speakers means that, for some, the hazard is not clearly or correctly portrayed, and risk is not properly understood, explained Trujillo Falcón.

Undocumented populations face particular challenges, not only around language accessibility but also in responding to perceived environmental risks, Trujillo Falcón explained, and policies around immigration can seriously complicate risk communication. People must weigh the risk of staying put in the face of a dangerous weather hazard or evacuating but getting arrested if identified as an undocumented immigrant. A 100-mile zone from the coast or international borders is the jurisdiction of the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), which gives officials the right to stop and search people suspected of illegal immigration without a warrant in this zone.1 Trujillo Falcón recounted how, during Hurricane Harvey, President Donald J. Trump ordered ICE to keep immigration checkpoints open but local officials countered that order and kept the checkpoints closed. Even then, however, large groups within immigrant communities did not evacuate. Under the current administration, checkpoints are ordered to be closed during times of evacuation, a decision that, Trujillo Falcón noted, prioritizes saving lives, regardless of an individual’s immigration status.

A third challenge that arises around risk communication for multilingual populations—especially Spanish-speaking people across North and South America—is cultural and community differences in understanding of what weather might bring what impacts. Messaging could be tailored to the specific community, in terms of not only translation but also social context. Because of context, information might be either readily understood or confusing, and attending to this difference is important when crafting effective messages. Trujillo Falcón illustrated this point by noting that someone from Puerto Rico will be familiar with hurricanes, while someone from another area—Perú, for example—will have never experienced

___________________

1 More information about the 100-mile zone is available at https://www.aclu.org/know-your-rights/border-zone.

one. Thus, explaining what a hurricane involves might be redundant to a Puerto Rican, while comparing a weather event to a hurricane might be meaningless to a Peruvian.

Trujillo Falcón closed his presentation with a discussion of a grant project that he is leading at NOAA, which supports AI initiatives at the NWS to develop “neural adaptive translation software” that helps create translations of English messages into multiple languages, including Spanish, Vietnamese, and Mandarin. This AI produces automated translations that can be reviewed by forecasters, lessening their workload, especially in hectic times. So far, Trujillo Falcón reports that the NWS has had “great success,” not only in communicating key messages but also in providing context that might be necessary in that particular setting: “We’re able to bring people along from step one and say, this is what a hurricane hazard is. This is what you need to do. These are the recommendations that are involved in this. Let’s break it down from the very first step.” This software also integrates with geographic information systems (GIS) to identify the location of multilingual communities in the United States and to identify possible future collaborations.

Gillums then spoke about his work as FEMA’s statutorily established disability coordinator. He noted that, from his perspective, the largest factor in risk communication is not the message so much as how people tend to see circumstances in a light that is most favorable to them, leading them to make decisions based on that optimistic bias. This tendency aligns with uncertainty suppression, discussed by Padilla and Hullman in the previous panel. Gillums shared that, because of an injury sustained while serving in the Marine Corps, he joined the 61 million people in the United States who identify as, or are regarded as, disabled. As with language accessibility, the stakes were very high around disability and decision-making during disasters in the past. “The reality was, if you were disabled or of advanced age, you were more likely to die in Hurricane Katrina than most other survivor populations.”

Gillums highlighted the difference between safety and certainty that often shapes calculations that individuals make as they decide whether to heed alerts and evacuate. For many people, for example, the lack of safety inherent in evacuation is foreseeable unsafety, whereas whether a weather threat will actually impact them is not so predictable. Using his own experiences in the wildfires around San Diego on Labor Day weekend of 2005, Gillums described the difficulties around evacuation and other protective actions that people in the disability community face. He recounted his own process of rationalizing whether to stay at home or evacuate after hearing the voluntary evacuation order on television. Within “the window of uncertainty suppression”—when individuals have time to think before the threat hits—Gillums contemplated whether he should leave his house for a local football stadium where evacuees were advised to relocate. Despite having the intellectual capacity to think through the options, “in that moment, it became less about what was most safe, and more about what outcome seemed most certain for me.” He noted that he did not feel safe about either option, but he felt more certain that if he stayed home and nothing happened, he would be safer than if he evacuated to

the football stadium that he imagined would resemble the dire shelter conditions in Louisiana just a month earlier. For a time, it looked like the fire might reach him, and Gillums worried that he had made the wrong decision. Even in this moment, however, he knew that he might be unsafe at home, but he believed that his routine yet complex needs would be ignored in the stadium. “It wasn’t about whether I’d be burned alive. It was about whether anyone would understand my needs were important to my day-to-day living.” And the answer, he felt strongly, was no. He emphasized that for an individual living with a disability, their home is their sanctuary and place of peak autonomy and empowerment. Asking them to leave that sanctuary in anticipation of an event is an enormous burden because they may find themselves in an environment “where the uncertainty and potential for harm are profound to a point where it could have permanent implications.” For a person with a disability, “the world is unsafe all the time.” Therefore, the process of deciding whether to exchange one threat (staying home) for another (leaving home) can be very challenging.

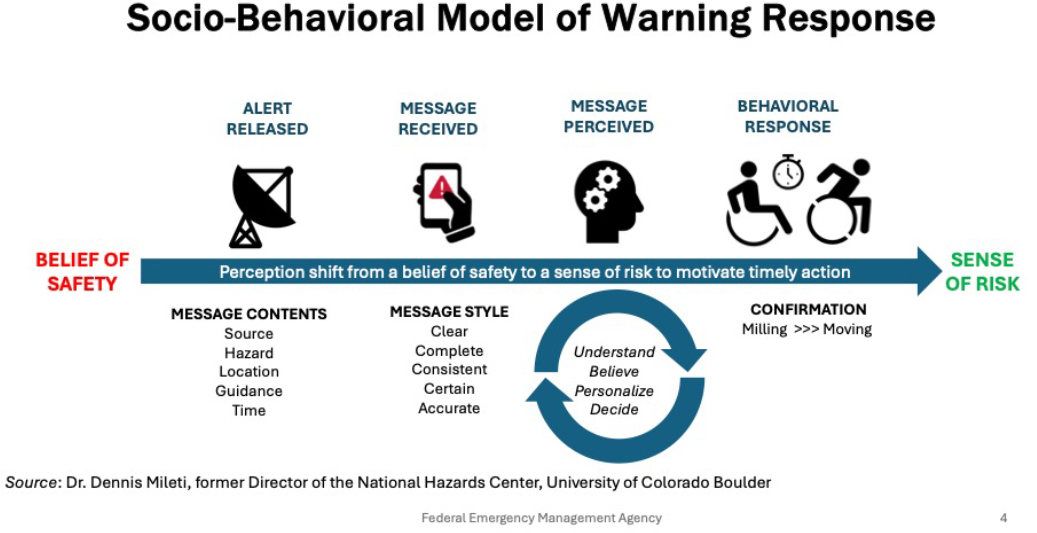

Drawing on Mileti, Gillums related how people process decisions to his own experiences and work (Figure 7.3). The decision-making process starts with the message contents —what an individual is being told, he explained. In his own case, the information that reached him did not make the fire seem too dire; although he received the order to evacuate, he processed this information alongside the various reports “in a light most favorable” to himself.

SOURCE: Presentation by Sherman Gillums, Jr. on February 6, 2024; adapted from work presented by Jeannette Sutton, PhD, at the Washington Partners in Emergency Preparedness webinar on Evidence-based guidance for effective alerts and warnings: The Warning Lexicon, November 28, 2023.

The second aspect of decision-making is how the message is sent: what language is being used, what associations are made (e.g., the meaning of a “bomb cyclone” related to a tropical storm in California to laypersons). “Message clarity is in the eye of the beholder,” Gillums noted, and, therefore, front-end stakeholder inclusion during message development is key. Working with the target audience to develop the message, and then to further test the message, can improve the message’s inclusivity.

Perception of the message is perhaps the most important aspect of decision-making, Gillums said. How do individuals understand the message? Do they believe it? Is it relevant to their circumstances, or could it be? Gillums explained that FEMA, in anticipation of a forecasted storm, reviews population data and other information to “triangulate ourselves into seeing a risk profile” and to better understand the individual needs of the communities it is trying to reach and serve who fall within the profile’s context. For example, when a tornado hit the historic city of Selma, Alabama, near the Alabama School for the Deaf, in Talladega, Alabama, Gillums’ team noted that the state needed to immediately secure American Sign Language (ASL) interpretation for the governor’s addresses to the public. Relationships between agencies and communities are critical to ensuring that messaging is crafted to reach the intended group.

The final aspect of decision making—the response—can be described as either “moving or milling,” explained Gillums. Whether people take action is influenced not only by the messaging, he explained, but also by who is making the decision (e.g., when fathers as decision-makers tend to stay, whereas mothers as decision-makers tend to go). Clear, effective communication involves a certain level of cultural competency: understanding who is likely to be participating in the decision, who is leading discussions, and who is likely to encounter the information. Gillums also stressed that messaging needs to be personalized to be effective. To illustrate this point, he recounted a conversation with a woman living on Sanibel Island who evacuated during Hurricane Ian and lost some neighbors who did not. She explained that, although the neighbors received the message about the risks and the order to evacuate, and although they “sensed danger,” they did not believe the message was directed at them. The message did not feel personal, and the risk did not seem different from that of storms they had survived in the past.

Gillums concluded by noting FEMA’s ongoing efforts to improve risk communication in this area, which include being more visible ahead of a storm by building relationships with communities, gaining a sense of the community and its needs, raising awareness, and helping communities prepare ahead of time. FEMA also aims to use language that speaks more fully to the disability community—for example, to indicate how to access transportation rather than simply giving an order to evacuate. Again, success depends on having strong connections with community stakeholders to more effectively strategize about communication.

The following discussion opened with a question from Sutton, the moderator, about whether specific words—especially jargon—are difficult to translate from one language to another using AI or within the disability community. Trujillo Fal-

cón highlighted the word “trough,” which can be translated as the place where pigs eat in some non-English languages. However, in areas where hurricanes are common, such as Puerto Rico and the Caribbean, a lot of good terminology already exists. Therefore, he explained, it is important to attend to regional differences in weather that correspond to differences in terminology. Working with certified translators is also very important, he noted, to better understand how dialectical varieties work and how best to communicate to different populations. Gillums noted that, on the one hand, people may not understand terms for impacts with which they are unfamiliar (e.g., lake effect snow), but, on the other hand, familiarity can also lull people into a false sense of security: they know what is coming and so, perhaps, miss details about the specific threat at hand. He further commented that “accessibility” means many things to many people and therefore no longer has consistent meaning.

A second question, from Schumacher, raised the idea that calculations around evacuation and other protective actions might be as much about resources (i.e., a person’s perception of how well they will be treated and whether their needs will be met at a shelter or other site) as they are about communication itself. Gillums reiterated that clear, accessible communication is essential. But so, too, are resources, especially as climate change makes places vulnerable in new ways; this situation poses a dual challenge in that places are not prepared for such hazards and people are under-resourced. Helping people to understand “what they’re up against” is critical, he explained; even if they cannot easily access resources, knowing what is needed can help people find ways to prepare and protect themselves.

Micki Olson asked the third and final question of the discussion: What policy does your agency need to create or implement? Trujillo Falcón responded that believes an agency should clearly define translation. He noted that in their work to develop bilingual risk communications, agencies supported the concept of translation, but in a literal sense so that the English and Spanish messages lined up perfectly. This approach, however, does not reflect how bilingualism and translation work, Trujillo Falcón noted: many words cannot be technically directly translated. “If we are more concerned about translating the meaning of given words overall, we’d be able to move a lot quicker” in producing messages that are consistent and resonant within the target communities.

Gillums responded that he advocates for FEMA to adopt a proactive rather than a reactive posture. Proactivity means not waiting too long to prepare people or ask them to take action: “There becomes a point when there are diminishing returns to the communication [of risk and what actions to take] because people have no decision-making capacity.” Gillums stressed that this point is often reached sooner than people realize, and that if a storm is anticipated, then the time to engage in some of the important preparedness work and decision-making has passed. He acknowledged that agencies might have good reasons for adopting a reactive posture. Nevertheless, preparedness before an event is on the horizon is essential to keeping people in the disability population—and in general—safe.

HIGH-LEVEL SUMMARY OF SESSIONS FIVE AND SIX

Risk communication is about both the content of the message and the people who receive it. This central theme from sessions five and six was summarized by Andrea Schumacher, Jeanette Sutton, and Ann Bostrom. Bostrom commented that effective risk communication involves understanding how members of the general public make meaning from visualizations, and then developing products that align with those conventions and practices. Several panelists stressed the importance of “talk[ing] with intended audiences to learn what they think” about terms, communications products, and other aspects of messaging. Schumacher noted that public-private partnerships offer a promising opportunity to conduct this research. The perspective of social scientists is valuable; they should be engaged to advise on reception issues and audience understanding early in the product development process. “Thoughtfully entangling” these disciplines are tricky, Schumacher noted, and “transitioning social science research to operations requires a thoughtful approach that includes co-development evaluation and really, an iteration of those processes.” The discussions raised awareness of audiences who are not being listened to, and of the unmet, unseen needs of “hidden communities,” including immigrant populations.

A second variation on the theme of attending to both content and reception was the concept of customization, localized messaging, or messaging otherwise specific to a time, place, audience, and/or moment in the event. Schumacher commented that different messages are needed at different times and for different events, but also at different points within those events. The technology demonstration provided an example of how new technologies might support increasingly localized messaging (whether personalized or geographically targeted).

Another variation on this theme in found in how the process of communication intersects with uncertainty, which can have a meteorological or a more personal dimension. Messaging that foregrounds uncertainty and probabilistic information often changes to more deterministic messaging over the life of a storm, Schumacher explained; however, even in the most deterministic-sounding products, probabilistic information still underpins the forecast. “There are no 100 percent forecasts.” Thus, useful information will always come with uncertainty. She pointed to a tension revealed by the panelists between the data showing that “people make better decisions with uncertainty information” and research showing that simple messaging and plain language are better for communication. The solution here is not either/or, but rather the development of a range of messaging strategies. Schumacher reiterated that more research is needed to know when, why, and for whom various communications approaches are effective. Bostrom noted the challenges inherent in communicating uncertainty via visualizations, which are often misunderstood by the general public. The many examples provided by panelists revealed the difficulty of finding an “intuitive and heuristic way of processing uncertainty communications” that guides readers to an accurate understanding of the situation. “Convention misalignments” can contribute to misunderstanding of

visual information, and, again, research is necessary to improve knowledge of how people understand uncertainty through a variety of visualizations. Evoking another type of uncertainty, Sutton recalled Gillums’ comments about how and why people, in their decision-making, might prioritize certainty over safety.

Another, and related, major theme of sessions five and six was plain language. Bostrom highlighted the ongoing conversation about using simple language and avoiding jargon. Sutton noted the problem of “semantic satiation,” or the way a word loses urgency and meaning with repetition. Schumacher, in her mention of the tension between uncertainty and simple language, highlighted the importance of a spectrum of different messaging strategies.

Finally, partnerships between the public and private sectors yield opportunities for more and better research, noted Schumacher. Sutton added that new technologies provide more avenues for information dissemination. Bostrom noted that partnerships support a diverse array of perspectives and approaches and echoed a discussant’s suggestion for the collaborative inclusion of “different populations, different audiences, different decision makers, different technology sciences, and different social sciences.”

This page intentionally left blank.