Strategic Report on Research and Development in Biotechnology for Defense Innovation (2025)

Chapter: 2 Biotechnology for Meeting National Security Needs

2

Biotechnology for Meeting National Security Needs

Advances in biotechnology, or “technology that applies to and/or is enabled by life sciences innovation or product development” (National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2022), present vast opportunities to “grow the United States economy and workforce and improve the quality of our lives and the environment.”1 Throughout the past several decades, advances in biotechnology have enhanced our understanding of living systems and enabled the application of the “design, build, test” cycle to the life sciences (Science Buddies, n.d.). Biotechnologies can be used to manipulate living systems and their natural processes to create biologically-derived products or biological entities with novel biological properties or functions. Biotechnology products vary widely and may include vaccines and therapeutics for human and animal use; engineered organisms that improve crop yields and biomass, drought resilience, and resistance to pests; or organisms that help to address environmental contaminants (Gamble and Zarlenga, 1986; National Research Council, 2011; U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2024). These advances and applications focus on altering living systems to address the health of other living systems, whether humans, animals, plants, and even other microbes. Beyond these applications, biological materials, knowledge, and data are being used to produce industrial chemicals and precursors, animal tissue for use as actuators, microbes as potential sources of electrical energy, and DNA as a possible means for long-term information storage (Galanie et al., 2015; NASEM, 2020, 2022a, 2022b, 2023a, 2023b; Sanders, 2021).

The capacity to design and engineer the genomes of living organisms was a key paradigm shift in biotechnology when molecular biology tools were first developed in the 1970s. Since then, basic and applied life sciences and their convergence with other scientific disciplines have led to numerous advances in human health and medicine, agriculture, and environmental protection. Now, these biotechnology tools, combined with knowledge about complex biological systems and pathways, can be used outside of their traditional sectors of health and agriculture to design and develop engineered living systems to produce a variety of materials including industrial and other high-value chemicals, energetics/propellants, materials, sensors, coatings, textiles, or other commodity-driven products (Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, 2018).

Biotechnologies are being developed for production of biofuels and/or biofuel precursors to replace current fuel sources that contribute to climate change and other environmental instability and provide new sources of fuel in military arenas (U.S. Department of Defense, 2024; Xue, 2021). Engineered living sys-

___________________

1 See Exec. Order No. 14081, 87 C.F.R. 56849 (2022), https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2022/09/15/202220167/advancing-biotechnology-and-biomanufacturing-innovation-for-a-sustainable-safe-and-secure-american (accessed August 22, 2024).

tems can be developed for bioremediation of contaminated environments (Dua et al., 2002), waste treatment (Farid et al., 2023), and alteration of plants and animals to reduce their contribution to environmental degradation (Petersen, 2018) or to increase their tolerance of changing environmental conditions (Gu, 2021; U.S. Department of Agriculture, n.d.). Biotechnologies are also used to enhance capabilities of microbial living systems that naturally make cement-like molecules (Air Force Research Laboratory, 2023; Edwards, 2022; Simpkins, 2022), sequester carbon (U.S. Department of Energy, 2021), produce thread-like materials (Gibbons and Crumbley, 2024), generate electricity, emit light (Shakhova, 2024), mask visible or auditory signals (Branstetter and Sills, 2022; Diamond Light Source, 2023; Sitaraman, 2024), leach minerals (Jaiswal and Srivastava, 2024; Ji et al., 2022; Urbina et al., 2019), or any other uses not often thought of as biological or to harness the properties of biological materials for non-biological uses (e.g., biorobots and DNA-based information storage) (NASEM, 2022b; Woodall, 2023). Within this relatively unexplored “biological space” lies opportunities for rapid innovation in biotechnologies and biomanufacturing capability, a reality that has gained interest by U.S. competitors and the national security and defense community.

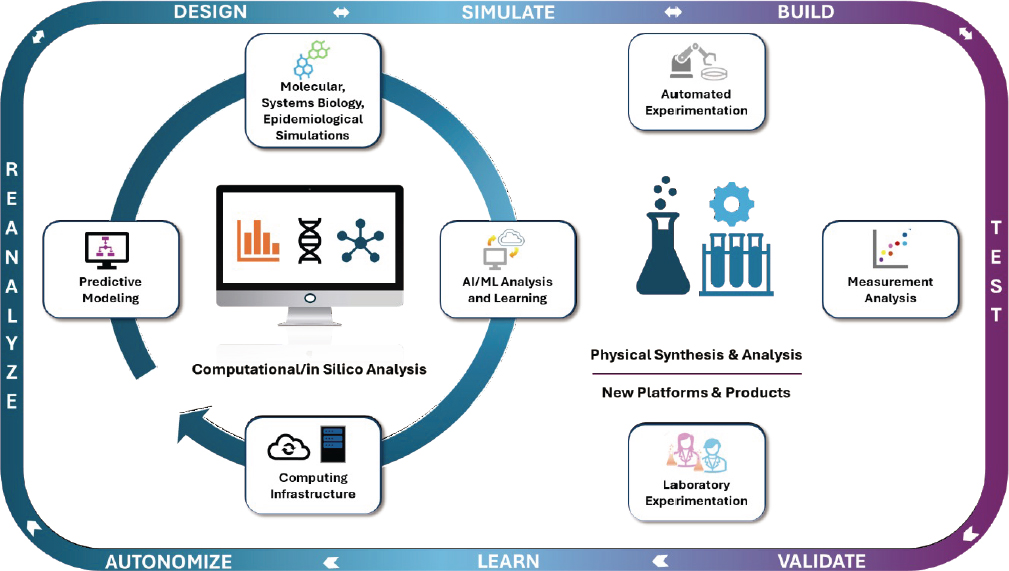

Rapidly advancing AI technologies, of which many different types exist, are transforming our approaches to discovering and understanding patterns in large complex data, building predictive models for the behaviors and interactions of complex systems, and accelerating biological models and design (Stevens et al., 2020). Further, machine learning (ML) algorithms running on computer systems with edge and high-performance computing (including graphics processing units) are learning to predict the properties and behaviors of biosystems. These algorithms increasingly are able to assess the uncertainties of their predictions, enabling some AI models to design experiments that would generate data in simulations or physical experiments, which would reduce the uncertainties. These capabilities include public artificial intelligence (AI) resources as part of the National Artificial Intelligence Research Resource.2 Bringing these tools together with advances in biotechnology and automated experimentation enables interlocking and mutually supporting computational and experimental design-test loops (Figure 2.1).

SOURCE: Created by members of the National Academies Committee on Biotechnology Capabilities for National Security Needs—Leveraging Advances in Transdisciplinary Biotechnology.

___________________

2 See https://new.nsf.gov/focus-areas/artificial-intelligence/nairr (accessed August 22, 2024).

The intersection of AI/ML, automated experimentation, and biotechnology represents a transformative frontier for defense innovation and all sectors contributing to the bio-based economy. As emerging technologies continually reshape global security dynamics, leveraging these advancements offers unparalleled opportunities to enhance national defense capabilities. As the global security context evolves, the synergistic application of AI/ML, automated experimentation, and biotechnology offers unprecedented opportunities to address and forecast emerging threats, improve operational efficiency, and drive transformative advancements in defense. Such application will support the goal of addressing critical national security needs such as supply chain resilience, global leadership in norms and safeguards for science and technology, and growth of the U.S. bioeconomy and biomanufacturing capacity.

APPLICABILITY OF AI/ML AND AUTOMATED EXPERIMENTATION IN BIOTECHNOLOGY

Robotics and advanced computation are being used to accelerate research in biotechnology across nearly all sectors. Computational methods have been developed and used with biology since the 1950s to help scientists solve challenging biological problems (Donkor et al., 2024; Gauthier et al., 2018). The increasing amounts of DNA sequence data being produced and increasing computing power in the 2000s allowed scientists to analyze genomic data at scale, which led to new opportunities across a diversity of life sciences fields, including precision medicine (National Research Council, 2011). Opportunities for understanding humans, animals, plants, and microbial systems were further enhanced by the inclusion of other data types, including image and text (e.g., gene and protein names). Algorithms that enable data mining, data fusion, data integration, image and speech recognition, natural language processing, ML, Bayesian analysis, social network analysis, agent-based simulations, and other modeling approaches provide opportunities for scientists to analyze and integrate the increasing amounts of biological data to examine biological phenomena across various fields (AAAS-FBI-UNICRI, 2014; Birrell et al., 2011; Keeling and Eames, 2005). In the early 2010s, scientists were integrating genomic data, physiological data, electronic medical record data, and other information from patterns of life to assess the risk of chronic diseases in individuals, all of which contribute to achieving precision medicine (Collins and Varmus, 2015; Gambhir et al., 2018). Computational and statistical approaches, particularly those grounded in mechanistic modeling and data-driven methodologies, have become essential tools for simulating and understanding the dynamics of infectious diseases at the population level. More recently, these approaches have been used for real-time forecasting, enabling the integration of diverse data sources, such as genomic data, mobility patterns, and clinical surveillance, to predict impacts with quantified uncertainty (Cramer et al., 2022; Reich et al., 2019). As new algorithms for AI, of which many models and methodologies exist, increased and new analytic capabilities were presented, researchers began to use some of these tools to help design engineered organisms to produce chemicals and other molecules or other specialized functions (Chan et al., 2019; Sanchez-Lengeling et al., 2017).

Although definitions of “artificial intelligence” and “science” are endlessly debated, an inescapably deep intersection exists between both: AI entails the automation of computational tasks, whereas science applies human cognition. AI tools include supervised and/or unsupervised learning, involve different computational and mathematical algorithms to integrate and analyze data, and rely on existing data differently. Supervised learning, which is used by most biological design tools, relies on the existence of high-quality, unbiased, and complete data to train and validate the algorithms. More advanced biological design tools aim to predict molecular structures, design novel molecules, and aid in engineering metabolic pathways among other similar functions (Appleton et al., 2017; Carbonell, 2021; Jumper et al., 2021). Unsupervised learning uses unlabeled and/or partial data to generate results that may be generalizable, which some researchers propose are useful for analyzing a vast majority of biological data, including image and text-based data (Akçakaya et al., 2022; Kalantari, 2016; Pastore et al., 2023; Song et al., 2017). For the purposes of this report, all of these algorithms are grouped into a single phrase, artificial intelligence/machine learning, for ease of writing.

In recent years, AI/ML has demonstrated a remarkable and growing capacity for tasks involving sensing (Trentin et al., 2024), inductive reasoning (Jin and Savoie, 2024), autonomous planning, (Boiko et al., 2023), and autonomous robotics at varying levels of performance and with the potential for functioning faster and with greater computation capacity than humans. Despite these advances, AI/ML and automation cannot replace the scientific method of truth-seeking through iterations of observation, hypothesis generation, and experimentation in the near term (Priani, 2021).

Most recently, advances in and use of AI/ML models with biological data have led to significant promise across a variety of sectors:

- Health. Over the past decade, the integration of AI into health sciences has significantly advanced, with researchers using ML and deep learning to improve disease diagnoses, medical care, healthcare delivery, pathogen surveillance, and other clinical and public health functions. Some of the approaches include creating a learning health system, addressing supply-and-demand challenges, and predicting and analyzing health risks and disease impacts. These areas have been revolutionized by the integration of multimodal data streams including genomic sequencing, demographic and socioeconomic variables, electronic health records (Li et al., 2015; “Use of Big Data Leads to Discovery in Diabetes,” 2022), clinical surveillance data, and data from wearable devices (Acosta et al., 2022; Bajwa et al., 2021; Kline et al., 2022; Raza et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2023; Zhou et al., 2024a). For example, these methods have been used to study type 2 diabetes patterns using several of these data types.3,4 For biodefense, applications of AI/ML with health and biomedical data can inform the development of medical countermeasures (vaccines, therapeutics, and diagnostics); evaluation and monitoring of emergence and spread of pathogens of epidemic or pandemic potential; and assessment and prediction of natural, accidental, or deliberate biological incidents. Among the agencies that lead or are heavily involved in these and other related activities are the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs (OASD(HA)), Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Nuclear, Chemical, and Biological Defense Programs (OASD(NCB)), and the Defense Threat Reduction Agency of the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD); and the Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction Office of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security.

- Drug Development. Tools, such as AlphaFold and its successors, enable scientists to predict three-dimensional protein structures based only on its amino acid sequence with a high level of accuracy for known, highly-characterized proteins. This tool was developed using highly curated protein sequence and structure databases to train and validate the algorithm and built on years of computational design and deep learning approaches (Jumper et al., 2021). One of AlphaFold’s proposed applications is aiding and accelerating drug discovery, particularly for protein or small molecule-based products. Other tools employ different methodologies, such as graph neural networks and existing data on chemical and biological compounds and drug-target interactions, to enhance the drug discovery process by helping to identify novel drug targets, predicting structures of drugs, and screening candidate drugs (Qureshi et al., 2023). Tools, such as natural language processing, recurrent neural networks, and other AI models, can be used to analyze published literature to identify adverse effects, drug resistance, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of drugs, and toxicity among other critical information (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2023). These tools also can be used to aid in other steps of the drug development and testing process including in clinical trial design, participant recruitment, and data analysis; surveillance and analysis of post-market safety surveillance data; and biomanufacturing. The use of AI/ML tools, such as AlphaFold,

___________________

3 See https://health.mountsinai.org/blog/use-of-big-data-leads-to-discovery-in-diabetes/ (accessed August 22, 2024).

4 See https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26511511/ (accessed August 22, 2024).

- offer applications for designing novel medical countermeasures against biological agents, and rapid screening of existing medications for their activity against natural and human-made biological agents. The NIH, FDA, and Office of Chemical and Biological Defense of the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense Acquisition and Sustainment (OUSD(A&S)) are the primary agencies that work on developing or approving medical countermeasures.

- Agriculture. AI models are being developed to improve crop yields; reduce time and costs involved at different stages of agricultural production; monitor soil quality; and detect pathogens, pests and contaminants in water, soil, food, and production systems (Kesari, 2024; National Institute of Food and Agriculture, n.d.). Further, more nascent research aims to develop AI-assisted decision making (National Institute of Food and Agriculture, n.d.). AI/ML applications in agriculture can inform evaluation and monitoring of the emergence and spread of pests and/or pathogens in crops and/or livestock, and development of models for protecting agricultural and food systems from natural, accidental, or deliberate contamination with these biological agents. The U.S. Department of Agriculture leads U.S. government efforts on preventing and countering agricultural threats including terrorism in agricultural and food sectors. The U.S. Department of Homeland Security also plays a role in assessing the risks of terrorism in agricultural and food systems.

- Ecology. AI models are being developed across a variety of fields to monitor, analyze, and possibly address environmental challenges, including climate related impacts. Some of these efforts seek to address ecosystem related challenges such as biodiversity loss, spillover and spread of infectious diseases (Wilson, 2024), and conservation efforts (Berger-Wolf et al., 2017; Lahiri et al., 2011). Some ecological research is leveraging computer vision and image analyses at scale. AI/ML applications in ecological systems can inform design of living systems for remediation of environmental contamination from chemical, biological, nuclear, and radiological (CBRN) contamination, and modeling of risks and remediation of environmental contamination from these agents. OUSD(A&S) has supported research and development (R&D) of synthetic biology solutions for cleaning up contaminated environments, and the Environmental Protection Agency leads several efforts in assessing, preventing, and mitigating contamination from CBRN agents.

- Biosecurity and Biodefense. In 2021, the Bipartisan Commission for Biodefense highlighted the role that AI/ML can play in forensics and attribution, specifically for distinguishing engineered from natural biological agents (Bipartisan Commission on Biodefense, 2021). Others have suggested that AI/ML could be used to improve pathogen surveillance (Ganjalizadeh, 2023; Parums, 2023; Suster et al., 2024), screening of DNA synthesis orders (Business Wire, 2024), and development of vaccines (Gorki and Mehdi, 2024; Olawade, 2024; Sharma et al., 2022). Numerous agencies across the U.S. government have both lead and supporting roles in achieving the U.S. biodefense mission as defined in the 2018 and 2022 National Biodefense Strategies (DiEuliis et al., 2019; Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, n.d.; The White House, 2022).

- Biomanufacturing. Biomanufacturing encompasses a diversity of sectors and products from pharmaceuticals to biologically-based chemicals and beyond. Biomanufacturing benefits from continuous process improvement, and AI/ML algorithms could be applied to previously inaccessible platform experimentation data to improve these processes. Collection and analysis of data from biomanufacturing using AI could enable process improvements and efficiency. Manufacturing of pharmaceutical, biotechnology, and agricultural products aimed at preventing, detecting, and responding to natural, accidental, and deliberate biological incidents is essential. Examples of products include medical countermeasures, laboratory tools and materials, pest- or pathogen-resistant crops, and/or vaccines or other products for preventing disease in livestock. These activities are the primary focus of various agencies, specifically the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

- (NIH, CDC, FDA, and the Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response), OUSD(A&S) for human medical countermeasures and pathogen surveillance, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture for crops and livestock. Beyond these sectors, the Office of the Under Secretary for Defense for Research and Engineering (OUSD(R&E)) has invested in building domestic capacity in biomanufacturing for bio-based materials, and the service laboratories work together to advance R&D in bio-based materials or organisms with unique functional activities for defense. AI/ML also may assist in developing standardized methods for engineering biology, which contributes to national security by ensuring the consistency and reliability of biomanufacturing for defense-related applications. The National Institute of Standards and Technology leads standards development. Finally, DARPA, the National Science Foundation, and U.S. Department of Energy are also part of the R&D ecosystem for engineering biology. Currently, efforts by the Engineering Biology Research Consortium seek to help DoD and the National Institute of Standards and Technology in developing technology roadmaps and standards for engineering biology (Taraseva, 2023).

A number of automated biotechnology laboratories (e.g., Emerald Cloud Lab,5 Recursion,6 Ginkgo BioWorks,7 and OpenTrons8) are revolutionizing the way traditional experiments and research are conducted by running millions of automated experiments, resulting in massive amounts of data. Automated experimentation via cloud laboratories can be controlled remotely from anywhere in the world using a software application (CMU Cloud Lab, 2021; NASEM, 2024). These laboratories are capable of increasing the number of simultaneous experiments that can be run at a given time (da Silva, 2024) and can be coupled to simulations such as digital twins of living systems to increase productivity and reduce cost during the design and early development phases (Portela et al., 2020; Tessler, 2022). Cloud laboratories also can communicate with each other and reroute data from one facility to another to run a necessary step using the needed equipment (AWS Events, 2023; Bose, 2024; Tessler, 2022). This feature allows several labs with specialized functions to operate in concert within a network (AWS Events, 2023; CMU Cloud Lab, 2021). Despite the promise of this capability, automating experimentation via the cloud may have unique cyber vulnerabilities, a concern highlighted in Chapter 5.

Translating these emerging AI capabilities into the automation of biotechnology research, development, and application presents both special challenges and opportunities. R&D in biotechnology are increasingly rooted in the engineering principles of iterative cycles of design, build, test, and learn. Unlike computational analyses that are conducted purely in an in silico environment, biotechnologies inevitably require creation of physical products, which can present significant resource, data, skill, and knowledge challenges. Yet, even in this uniquely challenging domain, AI is demonstrating improved facility across the component tasks in this structured design-build-test-learn cycle. AI, specifically large language models, is being developed for hypothesis generation, information elicitation, design and execution of digital and real-world experiments, and iterative adaptation based on results (Hutson, 2023; Zhou et al., 2024b).

Critical to these capabilities are the existence, availability, completeness, and robustness of the training, validation, verification, and input of biological data. Current open data repositories available to support model development for biotechnology development are broadly recognized as lacking. Although data repositories may contain large volumes of data, they often suffer from poor annotation (particularly lacking in inclusion of metadata), overrepresentation of organisms commonly used in laboratory experimentation, and conversely, underrepresentation of genetic diversity within individual species or adequately reflecting natural biodiversity (Chorlton, 2024). As a consequence, models, particularly supervised biological design tools, trained on these limited datasets are biased toward solutions already represented in the training data and thereby reduce model performance (Munsamy et al., 2024). Even advanced methods are unable to

___________________

5 See https://www.emeraldcloudlab.com/ (accessed November 1, 2024).

6 See https://www.recursion.com/ (accessed November 1, 2024).

7 See https://www.ginkgobioworks.com/ (accessed November 1, 2024).

8 See https://opentrons.com/ (accessed November 1, 2024).

predict the design of biological molecules with high efficiency if existing data related to those molecules are non-existent or poor. Data generated through automation in experimentation and data curation are bolstering data resources in biotechnology R&D. However, stubborn data silos, uneven curation standards, and existing automation limits continue to curb realization of the full potential of these data (NASEM, 2024).

In addition, actually realizing the benefits of use of AI in biotechnology at scale comes with enormous non-technological challenges of human coordination, limited by institutions whose speeds and efficacy are not improving exponentially (Wilson, 1998), unlike the technology itself. The datasets required for predictive models are growing rapidly to terabyte and petabyte scales and strain existing storage and data management resources (Rajeeva, 2024). The computing resources required for complex biological modeling and design workflows include large-scale data analytics, ML model training, and mechanistic simulation that can use hundreds or thousands of central processing units and graphics processing units. Biological laboratories often do not have access to or expertise in using these kinds of computing and data resources, such as supercomputers. Current capabilities for integration of these systems with automated experimental systems are also limited.

Expanding access to these state-of-the-art integrated capabilities for multidisciplinary, diverse public and private R&D groups may amplify the innovation potential of this convergence. Government investment in providing access to this class of infrastructure, tools, and capabilities will increase accessibility of this transformation of biotechnology capability to small biotechnology companies and university innovators working in these and other national security and bioeconomy application areas.

Conclusion 1: New, integrated approaches to using AI models and automated experimentation in biotechnology R&D that harness scientific networks, expand access to unique computational and experimental infrastructure, and accelerate progress toward significant benefits for national security and U.S competitiveness are needed. Standards for interoperability of data, AI/ML tools and libraries, and DevSecOps are critical to the computational capacity to support novel design and development of molecules and living systems.

AI-Enabled Biotechnology—National Security and Defense Nexus

DoD now has a strategy9 to develop domestic infrastructure needed to take defense-related biotechnology innovations from inception through scale up and military specification within the United States (Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering, 2023; U.S. Department of Defense, 2022). Although R&D in the defense sector is comparatively less than in other sectors (e.g., health, basic science, and agriculture), the expectation is that building a defense-focused bioeconomy ecosystem will accomplish several goals beyond fulfilling defense needs. First, the effort could produce unique biotechnologies that could have commercial civilian use and benefit other sectors, as was the case for the internet (“A Brief History of the Internet,” n.d.; “A Brief History of NSF and the Internet,” n.d.; Waldrop, n.d.) and GPS technology (“History of GIS,” n.d.). Second, it will fortify U.S.-based supply chains that aim to reduce national security reliability on foreign sources. Finally, it will catalyze the training of a needed biomanufacturing workforce, which includes skilled employees and multidisciplinary teams of scientists and engineers. Essentially, the DoD investment for defense needs could spur capacity-building in AI and/or cloud-based biomanufacturing across the broader U.S. bioeconomy (U.S. Department of Defense, 2024). For example, the DoD has invested in the biological manufacture of jet fuel precursor chemicals (Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, 2021; Graham, 2010), a technology that later could be licensed in fuel production for U.S. airlines (Ryskamp and Carder, 2017). Similarly, cement created by engineered algae currently being tested for its

___________________

9 See Exec. Order No. 14081, 87 C.F.R. 56849 (2022), https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2022/09/15/2022-20167/advancing-biotechnology-and-biomanufacturing-innovation-for-a-sustainable-safe-and-secure-american (accessed August 22, 2024).

durability under tank movements could find its way into many civilian construction venues, such as roadways, runways, or housing (Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, 2018).

Military-focused biotechnology efforts have been primarily sponsored through academic research programs and within DoD service laboratories. Commercialization of biotechnologies tend to occur through ad hoc, informal interactions among experts in different sectors (Gibbons and Crumbley, 2024). Biomanufactured products intended to replace a product within an existing defense supply chain need to fulfill the same military specifications for a given product type, be scalable, and be cost competitive. The standards and tools for measurements and novel bio-based products are critical to demonstrate comparative capability or advantage. Novel biotechnology products will require innovation as standardized manufacturing and scaling processes are being created. Such innovations likely could be spurred by AI/ML mining of biological data. Performance standards for novel products of the bioeconomy (e.g., how can microbiome treatments be more predictable in their performance, such as predictability of microbiome therapeutics) and standards for their production and safety also may rely heavily on the use of AI/ML.