Practices and Standards for Plugging Orphaned and Abandoned Hydrocarbon Wells: Proceedings of a Workshop (2025)

Chapter: 2 Orphaned and Abandoned Well-Plugging: Costs, Challenges, and Benefits

2

Orphaned and Abandoned Well-Plugging: Costs, Challenges, and Benefits

INTRODUCTION

The first session of the workshop, moderated by workshop planning committee member James Slutz, National Petroleum Council, presented a high-level overview of issues related to plugging orphaned and abandoned wells. Speakers were asked to highlight the history of well-plugging and associated regulations and to explore the scope and scale of current well-plugging challenges.

Slutz emphasized that given the lengthy and complex history of production and regulation in the United States, managing its orphaned wells is difficult. He highlighted the guidance of A Study of Conservation of Oil and Gas (IOGCC, 1964), which noted that because of differences in geology, production, marketing, and economics that demand flexibility at the local level, “uniformity of conservation regulations among the states does not exist” and would likely be an unrealistic expectation.

HISTORIC AND CURRENT WELL-PLUGGING EFFORTS ACROSS THE STATES

Lori Wrotenbery, Interstate Oil and Gas Compact Commission (IOGCC), provided a brief overview of state efforts to manage orphaned wells over the past several decades. She used examples from a few specific states, including the Railroad Commission of Texas’s drilling permit fee, New Mexico’s data management system, and Oklahoma’s Global Positioning System for reporting current locations of all known wells. Wrotenbery noted that the IOGCC works with all 38 oil- and gas-producing states.1 The IOGCC has released several key publications, including a 2019 report titled Idle and Orphan

___________________

1 This tally includes states that historically produced or are currently producing oil and/or gas.

Oil and Gas Wells: State and Provincial Regulatory Strategies.2 She indicated that this report informed efforts to provide funding for states to plug documented orphaned wells when the oil and gas industry experienced decreased demand and pricing issues during the COVID-19 pandemic. The 2019 report was updated with new data in 2021,3 and the IOGCC released a supplementary report in 20234 with information on states’ prioritization systems for plugging orphaned wells. In 2024, a supplementary report5 on orphaned well-plugging and site restoration was released, based on 3 years of survey data collected from individual states. She said that 141,959 orphaned wells were documented as of December 31, 2023 (with 29 states reporting), versus only 49,743 in 1992. States continue to improve their databases and examine historical records in order to refine their inventories, as states estimate that 250,000–740,000 wells remain undocumented.

Wrotenbery then shared other data from the 2024 supplementary report on the number of orphaned wells that were plugged in these 29 states. From 2021 through 2023, a total of 70,482 wells were plugged. States plugged more than 15,000 of those wells—nearly half of which were plugged using federal funds—and responsible operators plugged the remaining ~55,000 wells. The 2024 supplementary report also includes data on the costs associated with well-plugging, which vary widely within and across states depending on well depth, condition, location, and accessibility. Average state plugging costs ranged from $3,664 per well to $343,750 per well; across all 27 states that reported cost data, the average cost to plug a well in 2023 was $41,139. Although the states’ costs vary significantly, she mentioned that costs overall have increased over the past 6 years and believes this is due to inflationary factors, and that competition for contractors has increased.

ORPHANED WELLS: LOCATIONS, ATTRIBUTES, AND COSTS

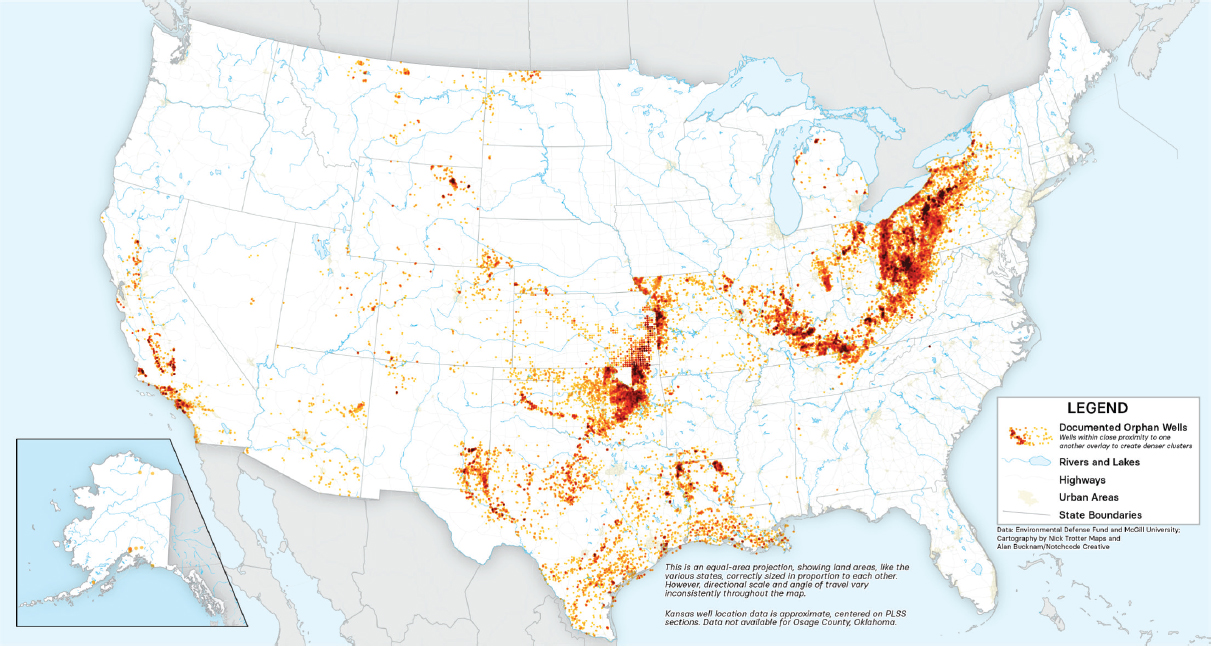

Adam Peltz, Environmental Defense Fund (EDF), noted a gap in the data collected on the locations of orphaned wells both because some states do not count orphaned federal wells in their totals and because an unknown number of undocumented wells remains. He indicated that of the 125,0006 documented orphaned wells that had been counted as of November 2021 across 30 states, many are concentrated in Appalachia, followed by Kentucky and Illinois, south central United States (including Missouri, Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, and Louisiana), the Rocky Mountains, and urban southern California (see Figure 2-1). He noted that 18 million Americans live within 1 mile of an active well, and 14 million Americans live within 1 mile of a documented orphaned well of those counted

___________________

2 This report is available at https://oklahoma.gov/content/dam/ok/en/iogcc/documents/publications/2020_03_04_updated_idle_and_orphan_oil_and_gas_wells_report.pdf.

3 This report is available at https://oklahoma.gov/content/dam/ok/en/iogcc/documents/publications/iogcc_idle_and_orphan_wells_2021_final_web.pdf.

4 This report is available at https://oklahoma.gov/content/dam/ok/en/iogcc/documents/publications/prioritization_report_7.10.23.pdf.

5 This report is available at https://oklahoma.gov/content/dam/ok/en/iogcc/documents/Idle%20and%20Orphan%20Wells.pdf.

6 As mentioned by Wrotenbery, this number increased to 141,959 by the end of 2023.

SOURCE: Environmental Defense Fund, 2021.

by late 2021 (Boutot et al., 2022); furthermore, an overlap exists between locations with high concentrations of active wells and marginalized communities.

Peltz highlighted the increased efforts of several states to plug orphaned wells with Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) funds—especially Kansas, Texas, Louisiana, and Kentucky—and he estimated that the total number of wells plugged in the United States with these funds is now approaching 10,000. He echoed Wrotenbery’s comment that the estimated costs to manage orphaned wells vary considerably within and across states, especially because some calculations only include plugging costs and not remediation costs. For the most part, states with straightforward topography and geology and shallow wells have lower costs. Although well-plugging can be costly in some locations, he noted the associated benefit of job creation in the oilfield service sector. For example, in Louisiana, many thousands of job-years could be realized from plugging the state’s ~17,000 idled wells.

Turning to known attributes of oil and gas wells, Peltz referred to a study of 82,000 documented orphaned wells, which found that much is known about well type (e.g., oil vs. gas), with data available for 83% of those documented orphaned wells. Less is known about well depth, with related data available for 50% of the wells, which leads to challenges in estimating accurate costs to plug wells. Even less is known about last production date (data are available for only 16% of the wells), which is a key factor in determining how to plug a well (Boutot et al., 2022).

Drawing on data from another study of the same 82,000 documented orphaned wells (Kang et al., 2023), Peltz described environmental and locational attributes of documented orphaned wells. He indicated that although knowledge on the relationship between orphaned wells and groundwater quality and contamination is limited, protecting groundwater is a primary reason to plug orphaned wells, especially given how many of these wells are located within close proximity to domestic groundwater wells. For example, a study on behalf of the Ground Water Protection Council7 (Kell, 2011) analyzed records of water contamination related to oil and gas in Texas and Ohio and found that nearly 20% of the contamination cases could be traced to an orphaned or abandoned hydrocarbon well. He pointed out that wells that have been leaking for decades can cause significant contamination issues, which are especially expensive to address. Concerns also arise related to methane emissions and to air quality issues from other pollutants.

The study by Kang and colleagues (2023) also explored potential beneficial uses for documented orphaned wells, such as for energy storage and geothermal heat. Furthermore, sites of documented orphaned wells could be repurposed for wind and solar activities. However, Peltz noted that carbon sequestration in areas with high concentrations of documented orphaned wells is problematic—and even more dangerous in areas with an unknown number of undocumented wells.

In his closing remarks, Peltz summarized the results of an analysis conducted across nine jurisdictions of the written rules8 associated with the Ground Water Protec-

___________________

7 Kell, S. (2011). State Oil and Gas Agency Groundwater Investigations and their Role in Advancing Regulatory Reforms, A Two-State Review: Ohio and Texas. Oklahoma City, OK: Ground Water Protection Council.

8 Peltz noted that states have additional guidance that is not captured in these rules.

tion Council’s “Regulatory Elements for Well Integrity”.9 Sixty (of 175) issues raised by these regulatory elements were found to need improvement on, for example, identification of water intervals that need cement protections; protection of other natural resources; establishment of standards for cement quality, slurry prep and placement, and mix water quality; expansion of pre-plugging wellbore conditioning standards; and determinations for testing the plugs. He emphasized that plugging standards can always be amended as technology advances and highlighted the importance of identifying gaps and effective approaches as well as learning from one another’s experiences.

RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM FOR UNDOCUMENTED ORPHANED WELLS

David Alleman, Department of Energy (DOE), described the Office of Fossil Energy and Carbon Management’s (FECM’s) ongoing methane mitigation research program, which aims to quantify and reduce emissions across the natural gas supply chain. Part of that program focuses on developing tools, technologies, and processes to efficiently identify and characterize undocumented orphaned wells for plugging and abandonment prioritization.

Alleman highlighted current initiatives with which FECM is involved. First, he mentioned a funding opportunity announcement for the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA’s) Methane Emissions Reduction Program. A total budget of $1.3 billion is available to plug marginal wells and to deploy technologies to help small operators reduce emissions. When EPA’s new regulations are implemented, he indicated that these small operators will be better prepared to comply. Second, while the Department of the Interior’s (DOI’s) Orphaned Wells Program was given a budget of $4.7 billion as a result of the IIJA, DOE was awarded $30 million over 5 years specifically for its Undocumented Orphaned Wells Program. An additional $4 million from annual appropriations was also dedicated to this effort. With these funds, DOE is working with states, tribes, and federal land management agencies as well as with the IOGCC to develop technologies and techniques to identify and characterize orphaned wells that are not in the regulatory inventory. This program has nine priority areas: methane detection and quantification, well identification, sensor fusion and data integration with machine learning, well characterization, integration and best practices, data management, records data extraction, well database creation, and use of field teams. Furthermore, he referenced a Notice of Intent released in July 2024 for an upcoming funding opportunity announcement,10 with a focus on how states can address issues related to advanced remediation, wellbore characterization, and long-term monitoring of undocumented orphaned wells.

Alleman then turned to a discussion of the challenges of this work, particularly how to find, characterize, and plug undocumented wells. He emphasized that although

___________________

9 This analysis can be found at https://www.gwpc.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Well_Integrity_Elements_Revised_1_19_2021_002.pdf.

10 This Notice of Intent is available at https://netl.doe.gov/node/13935.

no “silver bullet” exists to identify undocumented orphaned wells, useful technologies include magnetic surveys, aerial and satellite photographs, LiDAR, methane measurements, and state historical records. Research continues to be conducted to improve sensors and, in particular, data processing. Drone technology currently enables much of the identification work, and large drones provide more payload and more capacity. However, he pointed out that land access challenges arise with the use of drones, which require permits or Federal Aviation Administration “beyond visual line of sight” waivers.

After the wells have been identified, they are characterized. DOE is developing technologies to evaluate well condition without entering the wells. His team is also working to identify a robust set of sensors that can locate orphaned wells efficiently at scale—for instance, wells that do not appear with magnetometry could appear in overhead imagery. However, he noted that significant effort is required to synthesize the data collected from multiple sources to try to locate undocumented wells. He added that states with many documented orphaned wells are likely to have a high number of undocumented orphaned wells; furthermore, states with the longest production history are likely to have the most undocumented wells. He estimated that 800,000 undocumented orphaned wells remain in the United States.

Once orphaned wells are documented, Alleman explained that they can be prioritized for plugging and abandonment. Plugging is difficult in cases in which little is known about the well, and costs of bringing equipment to the well to characterize it are high; therefore, he encouraged learning as much about the well as possible ahead of time. An additional challenge arises when plugging wells in ecologically sensitive areas that affect the infrastructure that can be built to reach the wells and the materials that can be used to plug them. He underscored that tradeoffs between environmental benefit and damage have to be weighed carefully.

COMMENTARY FROM STATE OIL AND GAS LEADERS

As the first session of the workshop continued, Slutz invited five state leaders to offer their perspectives on how the topics of the opening presentations relate to issues faced by their respective states.

Tom Kropatsch, Wyoming Oil and Gas Conservation Commission, emphasized that Wyoming has been plugging orphaned wells for decades and adheres to the same standards and regulations that the oil and gas industry uses to ensure protection of both the environment and public health and safety. When plugging an orphaned well, he pointed out the importance of considering a property owner’s current and future surface uses as well as the varied situations that states and federal agencies encounter. He stressed, however, that anticipating everything that could happen when plugging a well is impossible, and Wyoming’s regulations are thus designed to allow flexibility. This perspective may have influenced DOI’s decision not to create a standardized process across the United States for plugging wells.

Eric Vendel, Ohio Department of Natural Resources, indicated that because many of the current problems with Ohio’s wells were created between the mid-19th and mid-

20th centuries, various histories and vintages of wells are considered when planning to plug wells. The Ohio Department of Natural Resources established its orphaned well program in 1977, and $130 million of state funds has been used to plug wells. He underscored that developing the most applicable funding mechanisms is key to continuing this work; for example, in 2012, when the shale industry began drilling wells, Ohio law was restructured to base funding on a severance tax, which increased the budget to allow for more plugging. He also discussed the value of researching the longevity of cement and other plugging materials—although cements used in Ohio (i.e., Class L and Type 1L) have been tested in the laboratory with acceptable results, different situations and challenges arise in the field.

Danny Sorrells, Railroad Commission of Texas (RRC), noted that Texas has been plugging and re-plugging wells for more than 100 years, with 10 state rigs and 11 federal rigs currently active across the state. Over the past 42 years, ~48,000 wells have been plugged using state funds (~$500 million). In 2023, 762 wells were plugged with IIJA funds, and more than 1,000 wells were plugged with state funds. Like Kropatsch, he expressed his support for DOI’s decision not to pursue a standard approach to well-plugging across the nation. For instance, because of the varied geology across Texas, different approaches to plugging wells are used across its 10 districts. Expanding on Vendel’s suggestion, he said that current cementing practices are outdated and likely not the most effective. He encouraged the development of new cementing technologies—for example, alternate materials such as geopolymers could be studied further.

Don Hegburg, Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection, explained that Pennsylvania has a 165-year history of oil and gas development. Only 27,000 orphaned wells are documented out of the 330,000 wells that, according to historical records, have been drilled, and more than 200,000 of these wells were drilled prior to the 1950s. Thus, he indicated that Pennsylvania would be using its IIJA funds to locate and begin to address undocumented wells. Furthermore, Pennsylvania will be integrating drones and other technologies into the process for locating undocumented orphaned wells and will be developing protocols in consideration of pilot-scale surveys that will be conducted by the Environmental Defense Fund in Pennsylvania later this year. He observed that ~3,400 wells have been plugged over 40 years, and Pennsylvania encounters many of the same problems as other states—for example, geological and geochemical issues that deteriorate wells and casings. Pennsylvania also has thousands of unconventional wells and a history of deep mining, both of which further complicate the plugging process. He acknowledged that although Pennsylvania has robust plugging standards, they could be improved with new approaches that extend plug longevity (e.g., metallurgical technologies that use bismuth).

Bryan McLellan, Alaska Oil and Gas Conservation Commission, remarked that Alaska has several unique issues related to well-plugging. Accessing and plugging old, remote orphaned wells might cost millions of dollars and be limited to certain seasons (e.g., driving across the tundra in the summer is impossible, and an ice road is required in the winter). Often helicopters are used to reach well sites, many of which are discovered based on 100-year-old hand-drawn maps. Thus, he expressed his interest in collaborating with DOE to use magnetics to locate wells more easily in remote areas.

He added that Alaska did not have a state-run orphaned well program prior to the IIJA era. Therefore, the initial IIJA grant of $25 million was used to establish the program, with assistance from other state agencies to begin contracting large-scale operations; to locate and investigate known orphaned wells; and to identify additional orphaned wells. Thus far, ~50 orphaned wells are known or suspected across Alaska—a number lower than that of many other states because Alaska has a newer oil and gas program, and the relatively higher cost of drilling wells is more compatible to working with major oil and gas companies who plug their own wells. The rest of the initial funding likely will be used to plug wells within 2 miles of existing road systems, and the $29.3 million IIJA formula grant is earmarked to plug Katalla Oilfield; however, he said that additional funding will be needed, given how difficult that site is to access.

OPEN DISCUSSION

Slutz moderated a discussion among the workshop speakers and participants. An online participant asked the speakers to provide a definition of “orphaned well.” Wrotenbery first indicated that “orphaned wells” and “abandoned wells” are not necessarily the same. EPA broadly defines “abandoned wells” to include already-plugged wells, orphaned wells, and wells that have responsible operators but that are inactive for a certain length of time. The IOGCC defines an “orphaned well” as one that is inactive and does not have a viable operator that is responsible for plugging and clean-up. However, to complicate matters further, she noted that terms and their definitions vary across states.

Another online participant asked how states prioritize wells for plugging, especially when funds are limited. Wrotenbery replied that the IOGCC’s 2023 supplemental report11 provides information on states’ prioritization systems, including the factors they consider and the scoring they use. She added that the IIJA’s orphaned well provisions defer to each individual state’s priority ranking system—and many of those priorities are first and foremost based on public safety, followed by groundwater and surface water protection.

Dwayne Purvis, Purvis Energy Advisors, inquired about the possibility of setting up a long-term monitor on wells that are not an immediate priority. Alleman responded that such a decision would be made by the states; however, DOE is searching for low-cost continuous monitoring approaches that could both identify problematic wells and measure the effectiveness of recently plugged wells.

An online participant asked about the relationship between seismic events and well failure. Workshop planning committee member Mary Kang, McGill University, explained that an analysis of data collected in British Columbia found a relationship between seismic events and areas where hydraulic fracturing is conducted. The study also measured methane emissions from plugged and unplugged wells; the study found a statistically significant relationship with higher methane emissions observed at plugged

___________________

11 This report is available at https://oklahoma.gov/content/dam/ok/en/iogcc/documents/publications/prioritization_report_7.10.23.pdf.

wells in areas experiencing more frequent earthquakes, as well as areas near earthquake occurrences. Eric van Oort, University of Texas at Austin, described a machine learning study for wells in New Mexico that found that the proximity to seismic events was a factor in well leaks—even for plugged wells. Given these correlations, Kang and van Oort suggested that further research be conducted.

Another online participant inquired about other extractive industry unknowns. Peltz said that at least three unknowns exist—the number of undocumented orphaned wells in the United States, the number of inactive unplugged wells in the world, and plug failure rates over time. Dan Arthur, ALL Consulting, highlighted work on projects in Venezuela, Ecuador, India, China, and Albania and encouraged sharing learnings with those working on the same types of issues in other countries.

An online participant posed a question about repurposing wells. Peltz replied that DOE’s geothermal unit is considering strategies to repurpose wells (with geothermal heat having more promise than geothermal power because the latter requires larger well diameters than those of many end-of-life wells). For example, in some end-of-life wells in Oklahoma, water is being injected into two wells and produced in two other wells to generate heat for local elementary and high schools. Additionally, wellbores could be used for energy storage. He mentioned that the Abandoned Well Remediation Research and Development Act would, if passed, direct $160 million to DOE to discover undocumented orphaned wells, examine plugging technologies (e.g., to address issues with cement), and consider beneficial uses of end-of-life wells. He added that repurposing wells and sites could generate new revenue sources to plug other wells. Alleman noted that although repurposing wells is desirable, many wells—especially older, undocumented wells with compromised wellbores—cannot be repurposed.

Michael Hickey, Colorado Energy and Carbon Management Commission, reflected on the funding sources for remediation. He suggested consideration of carbon credits for impacted soil. He said that industry partners are plugging wells at no cost to the state, but they do not touch impacted soils; if carbon credits were available for impacted soils, the atmosphere and the groundwater could be better protected. Arthur highlighted that many idled and marginal wells that have no operator might become orphaned but are not yet defined as such by the states. He proposed that this issue be addressed via the private-sector carbon market. He added that many wells are located around schools, businesses, and homes and in waterways where people are getting their drinking water, but the potential impacts are not yet understood. Complicating this issue further is that industry plans to drill 20,000 geothermal wells a year until 2050; although this would significantly increase the energy supply, he pointed out that those wells also would likely need to be plugged. Peltz said that those geothermal wells could be required to be bonded before being drilled, which could eliminate concerns about future orphaning. Wrotenbery noted that policy discussions continue on the specific issue of carbon credits. The use of the carbon credit market currently is prohibited for wells plugged or surfaces remediated with federal funds; however, states are asking DOI to reconsider that position because carbon credit participation could extend funds and allow states to plug more wells. Peltz posed several key questions about the relationship between plugging orphaned wells and the use of the carbon credit market: How do you estimate

how much methane is coming from wells? How long will the crediting period extend? What if you plug one well and the methane migrates to other wells? He emphasized that uncertainties remain about how to have a high-integrity carbon market.

Slutz noted that this discussion could inform the upcoming National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine consensus study on orphaned and abandoned wells. Peltz replied that the next steps could be to facilitate conversation between states and federal agencies on best practices and lessons learned, and to make a list of plugging technologies that can be further researched. Wrotenbery encouraged increased conversation with states to better understand their needs; she highlighted an IOGCC committee that identifies technical issues of greatest concern to regulators each year and then creates related webinars and research papers. Alleman also spotlighted the states’ wealth of knowledge and invited increased collaboration with DOE. In particular, he urged states to volunteer sites where the national laboratories could test new technologies for locating wells.

COMPILATION OF STATE STANDARDS AND PROCEDURES FOR PLUGGING AND ABANDONING WELLS

Rick Simmers, formerly of Ohio Department of Natural Resources, and co-authors were invited by the National Academies to submit a white paper compiling shared practices, statutory and regulatory standards, methods, policies and procedures, and designs of plans for well-plugging activities across state oil and gas regulatory programs.12 To gather data for this white paper, the authors disseminated a questionnaire for states about the elements of their respective plugging processes (e.g., identifying, locating, and characterizing wells and selecting materials). Responses to the questionnaire helped the authors to characterize the various methods used by program managers to address problems associated with orphaned wells.

Before discussing specific data from the questionnaire, Simmers provided a brief overview of drilling methods used in the United States over the past 150 years. The earliest method of drilling used a spring pole—essentially beating a hole in the ground to create a well. The next method relied on a mobile rig such as a derrick on a wagon. He explained that neither method reached significant depths, and both had limited capabilities. In Long Beach, California, where multiple rows of derricks were placed close together, when one well was plugged, the other wells would be affected and perhaps begin to flow. The cable tool rig was used to drill thousands of wells across the country. Particularly in the Appalachian Basin, some wells are still drilled using this method. More recent methods include rotary rigs that are modified to drill shallow portions of wells (and thus offer a less expensive drilling approach). He indicated that any combination of these more modern rigs could be used to plug a well.

Simmers noted that GPS data are often used to document orphaned wells. He stressed that advanced technology to help locate wells could be valuable, especially

___________________

12 This white paper is available at https://nap.nationalacademies.org/resource/28035/White_Paper_Orphaned_Wells_Workshop_Proceedings.pdf.

for complex settings like wooded areas or those with dense vegetation. Once wells are located, program managers face many challenges. For example, some wells might still have equipment in them; in other cases, program managers might be confronted with open annuli or a repaired well. When records of the original drilling do not exist, program managers may have a more difficult time developing plans to best plug the well. Furthermore, he continued, orphaned wells that are found in waterways are difficult to access and to plug—but it is important to prevent leakage from affecting the waterways. When wells are found in wetlands, program managers first determine if the wells were constructed in a way to protect groundwater, which may be defined differently by state. Potentially even more challenging to plug are orphaned wells located underneath infrastructure such as schools. To prevent this issue in the future, he suggested that GPS coordinates of newly located wells be shared throughout communities so that new structures are not constructed over them.

Returning to a discussion of the questionnaire, Simmers highlighted a few of the questions that state representatives were asked:

- Do you have a list of approved plugging materials?

- Do you define by regulation which plugging material should be used and which alternate materials are allowed?

- How are plug placement and volume defined by regulation?

- Are other items allowed to be used as plugs, as defined by regulation?

- What are the requirements around plug spacers and plug placement methods?

Simmers described some of the responses to the question about approved plugging materials. Alabama and Wyoming require the use of any American Petroleum Institute (API) cements and additives. Arkansas specifically requires the use of API Class A and Class H materials; however, Class A materials are becoming scarcer. Colorado focuses on specific performance criteria instead, requiring cement to reach 300 psi after 24 hours and 800 psi after 72 hours at 95 degrees. Oklahoma and Pennsylvania are particularly interested in performance standards such as compressive strength and permeability for plugging materials. He mentioned that all states that responded to the questionnaire (from here forward referred to as “respondents”) considered Portland-based cement as a default plugging material; furthermore, most of the states’ programs have both prescriptive and performance-based measures for the plugging material.

Simmers explained that all respondents have processes in place to approve the use of alternate plugging materials and equipment. These materials and equipment might be part of either a primary or secondary plugging plan. Generally, respondents recognize instances in which a primary plan to plug a well will not work, and all respondents have a provision to consider an alternate plan, alternate materials, or both. However, he stressed that alternate plans typically undergo a rigorous review and approval process to assure protection of people and resources.

Once materials have been selected and approved, Simmers noted that the next step is placing the materials in the well to plug it. Some states’ regulations identify the isolation of production and target zones (e.g., a mineral resource of future value) as a

key consideration for plug placement methods, and all respondents’ regulations require the isolation of “protected water.” Some respondents define specifically how to place plugs—for example, Arkansas allows the use of pressurized cementing for plug placement or the use of a dump bailer (i.e., gravity cementing). States that do not define how to place plugs choose their methods based on individual well constructions and plug requirements. Pressurized systems are the most popular choice, he explained, when well construction allows for them.

Summarizing general approaches to plug placement, Simmers mentioned that, for a bottom plug, some states require cement or plugging material to be placed below the production zone (and below perforations, if they exist) and additional cement to be placed above the production zone. When bridge plugs—a mechanical device that acts as a temporary barrier—are allowed, some respondents’ regulations require that a certain amount of cement be placed on top of them and that they serve as intermediate plugs, while others require that they are used only as temporary plugs. Lastly, when surface plugs are placed to protect water, respondents have very different approaches to determine required depths.

Simmers said that regulatory witnessing also varies significantly by state—for example, from 8 hours of advanced notification of plugging in Arkansas to 5 business days of advanced notification of plugging in Missouri. Furthermore, Arkansas can require a plug to be drilled out if notice of plugging was not received in the required timeframe. Work that might be observed by regulators includes tagging of plugs, monitoring of annular spaces and fluid levels, or placing of plugs. Although no regulatory program can witness every part of every plugging job, operators know that inspections can occur at any time. Additionally, all respondent regulations require the owner/operator or plugging contractor to submit reports (within ~30–60 days) detailing how the well was plugged, who was there, and if anything was left in the well that was not used for plugging; service company record attachments might also be required. He reiterated that all of these steps help to ensure that a well is plugged correctly and no longer contributes to human health and safety and environmental problems, and that land is restored for future use.

Discussion of the Compilation of State Standards and Procedures for Plugging and Abandoning Wells

An online participant asked if any states require an evaluation log of cement outside the casing prior to plugging within the casing. Simmers replied that many states require evaluation of proper backside isolation if a casing is left in a well. Furthermore, many states require wells to be plugged in a static condition (i.e., no flow), with isolation to the formation of origin.

In terms of regulations and approval of plugging plans, Arthur wondered if states and/or the federal government are considering how to account for the fact that the zones deemed worthy of protection may change in the future. Simmers said that some states have defined target zones, and states could benefit from periodically evaluating their targets and what they wish to protect (e.g., a carbon sequestration zone). He stressed that geology is a critical consideration.

Workshop planning committee member Nathan Meehan, Texas A&M University, asked if any states require long-term monitoring of methane emissions from plugged wells, reflecting that Alberta, Canada, requires testing wells for leaks 1 year after plugging. Simmers responded that after plugging, many states require the casing to be cut off down to a certain height (e.g., Ohio is 30 inches, some states require approximately 3–4 feet below grade), an identifying plate to be welded on top, and/or a monument (e.g., a pipe with identification information) to be installed. He added that Pennsylvania has long-term monitoring for mine-specific plugs, and in Ohio, some urban orphaned wells have permanent monitoring systems to detect gas. Kang posed a follow-up question about how often other wells in urban areas and areas with minable coal are monitored. Simmers noted that in Ohio, sampling would occur monthly up to 1 year; the regulator’s monitoring would stop when no leakage was evident from the port, and the local fire department could continue monitoring at the request of the property owner.

Reflecting on a new EPA rule that would require a forward-looking infrared (FLIR) camera observation of a well after it has been plugged, Peltz wondered how long it would take for a problem (e.g., micro-annulus, gas flow) to become apparent to the surface-level camera. Simmers remarked that how a well was plugged and verified determines how long it would be monitored. He emphasized the importance of verification throughout the plugging process to ensure that plugs are placed properly and are not leaking. He added that as cement is pumped, it might pick up natural gas that will be detected by the FLIR camera 1 day after plugging; however, the well is not actually leaking, and gas bubbles will disappear in a few days. Jesse Frederick, WZI, mentioned that hydrogen could be present a few days after setting a surface plug but would not be captured by a FLIR camera. A workshop attendee explained that in Ohio, a well has to be left open for 72 hours after plugging to ensure that no additional plugging work may be necessary. When gas is observed during that timeframe, samples are collected and typically hydrogen is seen instead of methane. In those cases, the attendee stated that the problem usually self-ameliorates over time and does not prompt re-plugging. Meehan suggested looking at wells plugged 6 months ago or 1 year ago; if one-third of those wells have noticeable volumes of methane, it is possible that a serious problem exists.