Practices and Standards for Plugging Orphaned and Abandoned Hydrocarbon Wells: Proceedings of a Workshop (2025)

Chapter: 6 Remediation, Reclamation, and Restoration

6

Remediation, Reclamation, and Restoration

INTRODUCTION

The fifth session of the workshop, moderated by workshop planning committee member Mary Kang, McGill University, highlighted approaches to remediation, reclamation, and restoration as well as associated challenges. She described “remediation,” which is a key step before reclamation that either follows or is part of the plugging process, as the clean-up of hazardous substances related to the removal, treatment, and containment of pollution or contaminants from environmental media such as soil, groundwater, or sediment. She pointed out that the terms “reclamation” and “restoration” are sometimes used interchangeably to represent the step that follows plugging. The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) defines reclamation as follows:

Reclamation helps to ensure that any effects of oil and gas development on the land and on other resources and uses are not permanent. The ultimate objective of reclamation is ecosystem restoration, including restoration of any natural vegetation, hydrology, and wildlife habitats affected by surface disturbances from construction and operating activities at an oil and gas site. In most cases, this means a condition equal to or closely approximating that which existed before the land was disturbed. (BLM, n.d.)

Kang explained that because “primary succession”—that is, what nature will do on its own without human assistance—can take 1–10,000 years, “assisting” that process can be valuable. She suggested that the particular type of land cover at well sites influences the approach to the reclamation process: forest and agriculture are the top two types of land cover surrounding documented U.S. orphaned wells (Kang et al., 2023). She added that reclamation is expensive; however, the benefits might outweigh the costs—for example, the immediate cost might be ~$6.9 billion, while the value of agricultural benefits and carbon sequestration realized over 50 years from restoring

oil and gas well infrastructure might be ~$21.3 billion (in 2018 dollars; see Haden Chomphosy et al., 2021).

Kang invited the session’s speakers to discuss the following questions: How do remediation and restoration options vary among sites? What are the key metrics (e.g., vegetation, wildlife, ecosystem services, fragmentation)? What long-term maintenance and monitoring efforts are needed? What data gaps exist, and how can new technologies address them?

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE ORPHANED WELLS PROJECTS

Forrest Smith, National Park Service (NPS), highlighted the challenges that the national parks confront, with ~2,600 oil and gas wells located across ~55 park units. He indicated that 1,200 of these wells have been inspected and inventoried; at least 45 orphaned wells have been documented, and more are expected to be found as inspections continue. More than 100 of the wells that have been inspected—some of which had been plugged previously—are leaking methane.

Smith provided three examples of completed NPS reclamation efforts. First, Ohio’s Cuyahoga Valley National Park, an urban park located between Cleveland and Akron, has 150–160 oil wells. The FF Hunt oil well was located near the base of a ski hill and had been orphaned for ~30 years; the topsoil was fouled from hydrocarbon and produced water spills and had to be removed and replaced. To reclaim this site, he explained that trees were cut down, the well was plugged, contaminated soil was scraped off, and a mix and till refreshed the soil. The site was then recontoured, the trees were brought back, and the site was reseeded and re-mulched. Another well in Cuyahoga Valley National Park, the EC Bender oil well, was partially plugged and orphaned ~80 years ago. Although NPS did not find soil or water contamination, the oilfield debris was significant. After the well was plugged, the site reclamation plan was similar to that for FF Hunt. He noted that each national park in the United States has unique documentation and goals for restoration, which is challenging; for example, Cuyahoga Valley National Park chooses to restore in a way that represents the park circa 1850.

Second, Smith said that in West Virginia’s Gauley River National Recreation Area, the Mower Lumber well was orphaned for more than 30 years and was leaking methane before being plugged. During plugging, NPS found that the flow line was connected to other active wells farther down the mountain, and the operators of those wells were notified after the flow line was plugged. Old mountain roads to the site were then recontoured, trees were cleared, and vegetation mulch was placed.

Third, Smith noted that in the Big Thicket National Preserve in Texas, the Arco Rafferty well site and the Arco Rafferty common tank battery both had soils contaminated significantly with heavy metals (e.g., chromium, barium, and lead). The remediation plan included removing 6 inches of contaminated soil, bringing in native soil to replace the contaminated soil, doing a mix and till, and collecting more soil samples, and the sites are now below the allowable levels for heavy metals.

Smith then discussed four NPS sites that likely will be reclaimed next. First, in the Guadalupe Mountains National Park in Texas, the Pure Oil well was drilled in

the 1920s and deepened in the 1940s; the oil company left the well since it had little economic value, and local farmers filled it with sediment and mud and produced water for their cattle. In the 1970s, the farmers then left the well after electrical lines to the site were destroyed in a storm. The site thus includes the original pump jack, a derrick frame that has fallen into the well site, an old tractor, tanks, and ample debris—all of which are hazardous to visitors and wildlife. Furthermore, the site is very difficult to access, with the need for mule trains, helicopters, and a 10-hour hike. He pointed out that after 50 years, items in national parks become antiquities that have to be preserved; therefore, this reclamation plan includes only removing the dangerous piles of debris and stabilizing the equipment.

Second, Smith described the Gherini well located in California’s Channel Islands National Park that was drilled in 1965. It was partially plugged but completely abandoned after a workover failure in the 1970s. However, the site is now an antiquity and archaeologically sensitive owing to native burial sites, so NPS is working with local tribes to avoid disturbing these sites during future reclamation efforts. Third, he stated that Jean Lafitte National Historic Park in Louisiana has many wells suspected to be unplugged. Because boat traffic is being impeded and contact could cause spills, wellheads, pier structures, and flowlines likely will be removed.

Finally, Smith mentioned that NPS also has funding to plug six orphaned wells that are actively leaking methane in the Big South Fork National Recreation Area in Tennessee and Kentucky. He pointed out that all of these wells were previously plugged and abandoned in the past 20–50 years. If funding is secured, an additional six wells could be plugged in 2025.

SURFACE RECLAMATION AND RESTORATION

Ron Krawczyk, Parsons Corporation, described his work in Michigan to clean up more than 1,000 legacy oilfield sites across four counties since 2006; in Canada to conduct more than 800 methane studies on well, subsurface, and surface casing vent flow; and in New York to manage pre–Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) funds and to plug more than 80 high-risk orphaned wells since 2018.

Krawczyk elaborated on the Parsons Corporation’s Orphaned & Legacy Well Programs, which locates and researches wells; evaluates risk factors; identifies the highest-priority wells to address; and identifies low-risk wells for lower-cost, more passive approaches. Parsons also conducts environmental investigations, re-engineering for access, and plug and abandonment work. To locate wells, he explained that Parsons leverages ground- and aerial-based magnetometry; the latter has been particularly helpful for cases in which the historical record locations are far from the actual site. In many cases, once the well is found, it has to be rebuilt before it can be plugged. He noted that Parsons also does turn-key orphaned well-plugging projects with private corporations and state agencies in Arizona, Michigan, New York, Texas, and Canada.

In addition to plugging and abandonment projects, Krawczyk said that Parsons conducts monitoring for the Michigan Department of the Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy’s Orphaned Well Methane Monitoring program with remote methane leak

detectors and high-flow instruments, which are all tunable diode laser absorption spectroscopy–based. Most leaks that Parsons confronts are small-scale (less than 20 g/hour), and he noted that the company has achieved field results of leak quantification down to 0.3 g/hour (nondetectable).

Krawczyk indicated that Parsons also has engaged in research and development on risk-based alternatives to plugging wells with complicated re-entry or those that are only leaking methane to the surface without other fluid impacts. For example, Parsons has patented a methane biofilter that can be placed on top of a well to enhance the biodegradation of methane (e.g., converting methane to carbon dioxide) and to prolong the time until plugging can be completed.

Furthermore, Krawczyk continued, Parsons participates in many remediation and decommissioning activities for oil, gas, and other industrial contaminants. For example, in Michigan, Parsons operates a landfarm facility where it treats 100,000–120,000 cubic yards per year of petroleum and salt-impacted soil for reuse as backfill on well sites; since the facility was built in 2006, more than 1.5 million cubic yards have been remediated. Parsons also removes World War II–era asbestos flowlines and operates a Class II underground injection control well for leachate disposal.

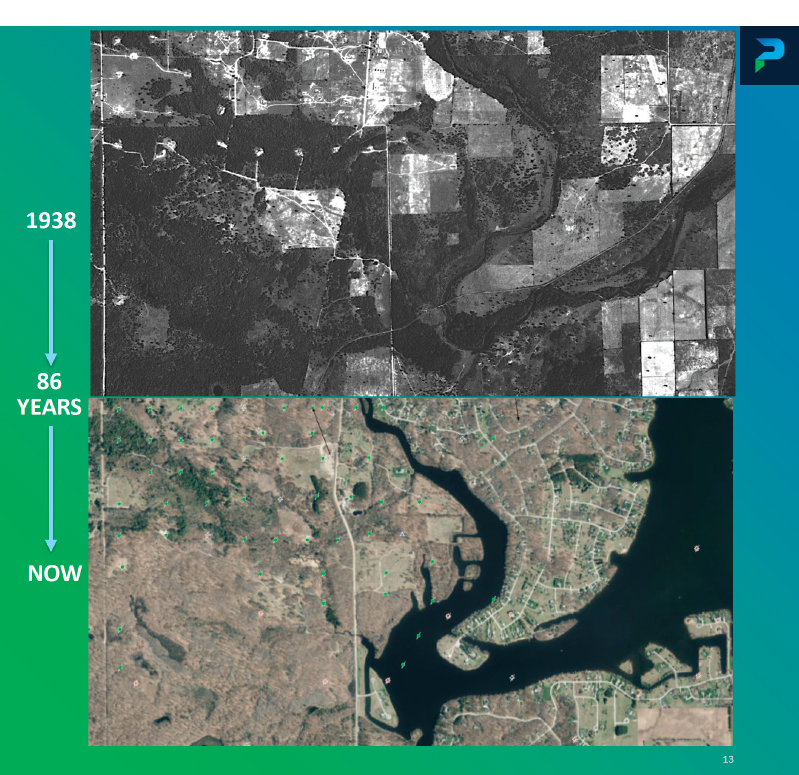

Krawczyk emphasized that many of the challenges associated with remediation and reclamation of legacy orphaned well sites relate to access issues. For example, early wells might be located next to rivers and streams or were drilled in uniform spacing patterns where the nearest point of solid ground was selected for the well. Krawczyk also noted that some wells, particularly those located in swampy areas, have small well pads that require additional engineering and permitting for a service rig and have impassable entry roads. Furthermore, he commented that access might be limited owing to hunting seasons, agricultural planning seasons, wet seasons, nesting and migration, fish spawning, endangered species habitats, forestry diseases, cultural areas, and seasonal recreation. Another challenge relates to the number of entities from both private and public lands that would ideally be engaged. Special considerations to affected parties include utility right-of-way, corporation-owned property, municipality-owned properties and roadways, and disinterested or adverse property owners. Yet another challenge relates to land use changes between the time the well was drilled and present-day—rural land might now be developed heavily, dry land might now be a swamp or a lake, and a clear-cut area might now be densely forested (see Figure 6-1).

He observed that modern infrastructure (e.g., electric, water, gas, sewers, and buildings) as well as oilfield redevelopment might create additional land use challenges that involve increased coordination with other parties. Many levels of permitting might be required, he continued, such as with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the federal government, state agencies, county agencies, and the Fish and Wildlife Service. These permits often drive restoration requirements, such as for certain seed mixes, soil erosion controls, finish grade evaluations, access roads, and other infrastructure. To minimize disturbance to communities and increase efficiency while working on orphaned well projects, he highlighted the use of early desktop reviews to categorize sites by complexity and estimate lead time for surveying, early engagement with affected parties, up-front drone surveys to pinpoint wellbore location and former access roads, and phased work queues.

SOURCE: Krawczyk, 2024; Michigan State University RS&GIS Aerial Imagery Archive (upper photo); State of Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy GeoWebFace Data Viewer (lower photo).

COLORADO’S ORPHANED WELL PROGRAM

Michael Hickey, Colorado Energy and Carbon Management Commission (ECMC),1 emphasized that the ECMC has embraced the IIJA’s suggestion to engage family-owned businesses. The businesses with which the ECMC partners have made significant adjustments, meet the new federal requirements for monitoring, data collection, and reporting.

Hickey explained that before accessing a site for plugging and abandonment and digging up well casing in Colorado, a remediation plan (Form 27) must be reviewed and approved. Thus, the planning process begins weeks to months ahead of the work. The

___________________

1 For information about the ECMC’s Orphaned Well Program and its annual reports, see https://sites.google.com/state.co.us/cogcc-owp.

remediation plan requires that once the wellhead is removed, confirmation samples will be submitted to verify that the dirt being left behind is clean. Additionally, a Notice of Intent to Abandon (Form 6), which describes plans for how the well will be plugged and includes a wellbore diagram, has to be reviewed and approved by the ECMC engineering group. He indicated that collaboration across the ECMC helps facilitate a smooth approval process. Form 42 is then distributed 48 hours before the rig is placed at the site, a second version of which notifies the local government designee that a well will be plugged in that person’s jurisdiction. After work is finished, a Form 6 Subsequent Report needs to be submitted to detail the actual plugging work that was completed.

Hickey conveyed that the ECMC’s pre-plugging methane monitoring is conducted using a variation of the chamber measurement approach that was described in the workshop’s previous session. He said that combining methods by using an opened-up, static-free bag to form a background on the upwind side of a well to minimize wind interference gives more accurate high-flow measurements. When optical gas imaging is used, that same bag provides a clean background on the infrared images, which also helps to improve the accuracy of the measurements.

As a result of Colorado’s new regulations, Hickey noted that the ECMC also is actively removing miles of flow lines. Several issues arise during this process, including that the lines cross several types of public and private properties and surfaces, are corroded, are more numerous than expected, and/or are filled with fluid and result in large clean-ups. When removing these flow lines, if an incidental spill is found, he stated that contractors are encouraged to clean up as much as possible. Furthermore, third-party professionals conduct ongoing monitoring and sampling throughout this work; photo ion detectors uncover hydrocarbons effectively, but inorganics are more difficult to detect and control.

When confirmation samples are positive and/or when messes are significant, Hickey underscored that remediations are difficult to schedule and to finish because repeat visits are often needed. He provided an example of the challenges of remediating a well site in which gas condensate had been leaking into the ground for 30 years, extending beyond ECMC’s initial perimeter and threatening domestic wells and adjacent homes. Sharing some of the maps and volumetrics of this site that were developed by a drone operator, he noted that while some of the soil that was removed was determined to be clean enough to be reused as backfill, 3,555 cubic yards of impacted soil were transported for disposal. He estimated that excavating and stockpiling the overburden; excavating, loading, transporting, and disposing of impacted soils; purchasing, loading, and transporting fill; and replacing the overburden and reclaiming the site cost $100 per cubic yard of impacted soil—a very expensive undertaking. He explained that after the remediation of this site was compete, reclamation experts performed soil treatments on the surface so that homes could be built on the site.

A MODERN APPROACH TO RECLAMATION

Brent Wilson, Red Willow Production Company, explained that the Southern Ute Indian Reservation comprises an area of 1,058 square miles in southwestern Colorado.

Red Willow Production Company was formed in 1992 to take ownership of the tribe’s energy resources within the San Juan Basin. Since then, it has expanded to include reserves and production in the Deepwater Gulf of Mexico and in the Green River and Delaware Basins.

Wilson indicated that state and local laws do not apply to the Tribe’s operations occurring within the Southern Ute Indian Reservation, and Red Willow’s operations within the exterior boundaries of the reservation are conducted under tribal and federal regulatory oversight. Wells on tribal leases are overseen by the Southern Ute Department of Energy, the Southern Ute Department of Natural Resources, BLM, and the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). He noted that reclamation projects are considered complete when the wells are released through the approval of Final Abandonment Notifications (FANs), after they meet the criteria of and pass inspection by the Southern Ute Department of Energy and BLM. This situation is unique, he continued, in that Red Willow (which is owned by the Southern Ute Indian Tribe) is the oil and gas operator and the regulatory body that works with BLM and BIA, and the tribe is also the landowner; this relationship has allowed Red Willow to prioritize reclamation practices and give the land back to tribe members to use as they wish.

Wilson stated that the reservation is located in a high-desert climate. Severe drought conditions have persisted for at least the past 10 years, creating challenges for reclamation with less spring moisture available to support germination. Red Willow aims to build an idled well program that accounts for and mitigates these drought and climate issues, which make reclamation a priority. He remarked that succession is the main goal in reclamation. The process begins with bare ground and annual weeds, and then moves to establishing perennial grasses and shrubs over a period of 2 to 4 years; from that point, he said that Mother Nature can establish a forest over 5 to 20 years. He encouraged states to consider during their planning processes how much time and effort are required for reclamation.

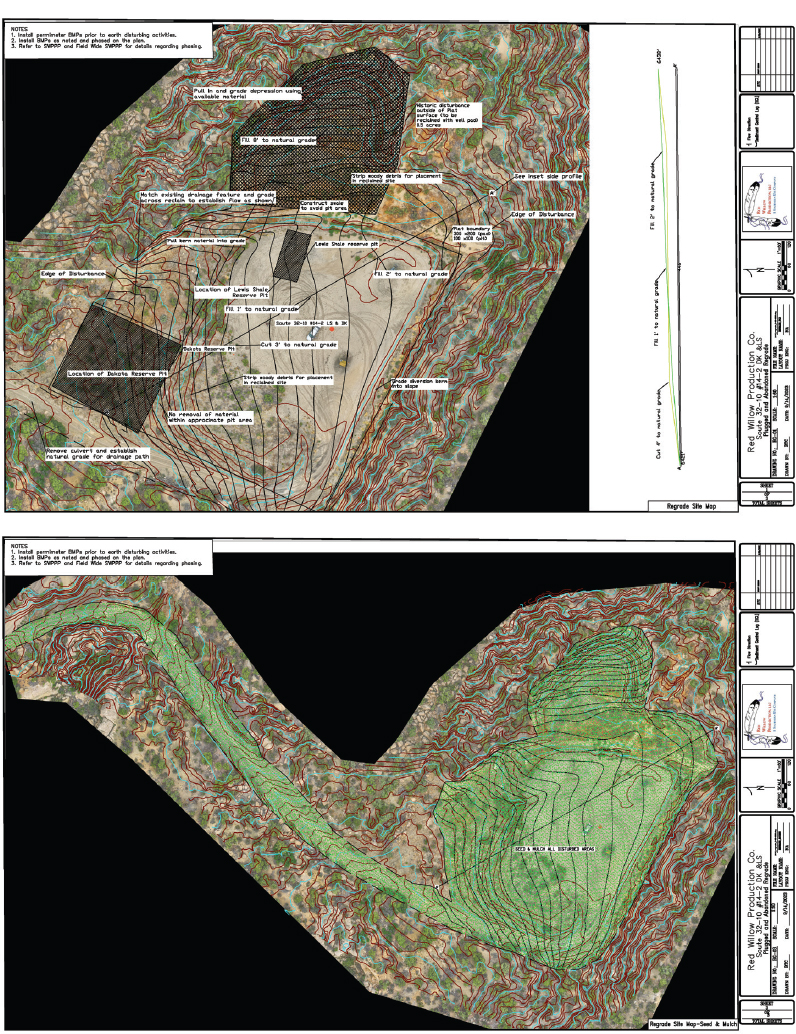

In 2019, Red Willow created an internal team to focus on the increasing number of idled wells and to develop new processes and techniques to reclaim locations efficiently and reduce plugging and abandonment liability, Wilson explained. This team leverages data to develop reclamation plans that include contour maps, seeding and fencing details, stormwater management, soil analytics, and prescribed application rate for soil amendments and mulch (see Figure 6-2). After generating these plans, the team communicates with the Southern Ute Department of Energy and tries to accomplish reclamation projects in a single attempt instead of having to return over the years to establish growth.

To capture some of the detailed topographic data included in these reclamation plans, Wilson indicated that Red Willow leverages consumer-level drone-based LiDAR technology. Drone photos are used to generate a three-dimensional model in AutoCAD, which is then manipulated to determine a final grading plan. The goal is to select contour lines and find their counterparts on the other side of the well pad, and then draw them to create a consistent flow of surface through the well pad. This maximizes the amount of time that the water can stay on the well pad without turning into a pond, encouraging a gentle drainage of the location. He emphasized that this preliminary work ensures

SOURCE: Wilson, 2024.

that something stable promotes succession, grows the species, and helps reclaim the area. Drone cameras are also used to monitor vegetation and track the success of the reclamation over time.

Wilson added that Red Willow has been working with several soil additives and new preparation techniques to help establish initial vegetation. For example, biosolids, which are by-products of the tribe’s wastewater treatment plant, are used to introduce nutrients back into the sterile soil. Biochar, produced from beetle kill trees in Colorado, absorbs contaminants, helps neutralize soil chemistry, and increases soil water retention. Surface soil flipping, a technique in which the top foot of soil is flipped, prevents ground sterilant remnants from weed spraying from directly contacting the seed bed. Furthermore, after realizing that straw mulch is ineffective in a windy climate with little rain, he said that Red Willow adopted the use of excelsior mulch for shallow slopes—which is difficult to apply but traps moisture in soil—and hydromulch for steep slopes—which is expensive but easy to apply.

In closing, Wilson noted that Red Willow and the Southern Ute Indian Tribe have experienced marked improvement in reclamation success as well as a reduction in time to receive FAN approval. The team strives to continue to identify and evaluate new technologies and techniques to drive progress on site reclamation.

OPEN DISCUSSION

Kang moderated a discussion among the workshop speakers and participants. She inquired as to how costs per well change when restoration is a high priority. Wilson reiterated that Red Willow prioritizes returning surfaces to the tribe so that they are able to hunt. He said that Red Willow budgets twice the cost of plugging for a reclamation project, but that amount does not include soil remediation. Wilson noted that about 1 in 30 remediations are a major effort. Smith noted that NPS also budgets heavily for reclamation, with the goal of achieving a nearly “pre-operation state” of the area. He added that this budget often depends on the difficulty of gaining access to sites. In some cases, surface cost can be double the downhole costs.

Greg Lackey, National Energy Technology Laboratory, asked about the proportion of well pads from which significant amounts of soil are being removed for remediation. Hickey replied that in Colorado, large sites like the one he described during his presentation have only been found a few times over the past couple of years; however, predicting where they will occur is difficult. Krawczyk said that one-half to three-quarters of the wells that his team has remediated have had significant amounts of soil removed, in part owing to the fact that many of the wells were drilled in the 1920s. He observed that having good site investigation, analytical samples, and environmental consultants is key to mitigating risks.

Adam Peltz, Environmental Defense Fund, observed that when salt is found in soil, it must be collected and discarded. He asked if any strategies exist to address groundwater contamination, in particular saltwater intrusion into a freshwater aquifer. Krawczyk agreed that if brine is left in the soil, reclamation will fail. In terms of the saltwater intrusion issue, he said that three-dimensional modeling techniques could help

deepen understanding of the problem. Hickey remarked that for an area of 38 acres where salt intrusion has occurred over the course of 50 years, his team is investigating the possibility of reusing an orphaned well that was designated as an injector: fresh water would be used to flush the salt kill, and the water would be collected and then reinjected. Krawczyk added that for those who have disposal wells, a pump and treat system could be used and old oilfield infrastructure could help remediate.

Dan Arthur, ALL Consulting, referenced the Department of Energy/National Energy Technology Laboratory’s research on brine-impacted soil clean-up using phytoremediation, soil amendments, and managed irrigation with produced water. He explained that the choice of solution depends on how quickly clean-up has to be completed; if the clean-up process could span a few years, more options are available. Krawczyk mentioned that phytoremediation has been effective for crude oil compounds. He added that in situ remediations often prompt more stringent regulations, owing to a concern about heavy metals and daughter compounds.