Practices and Standards for Plugging Orphaned and Abandoned Hydrocarbon Wells: Proceedings of a Workshop (2025)

Chapter: 5 Environmental Risks and Monitoring

5

Environmental Risks and Monitoring

INTRODUCTION

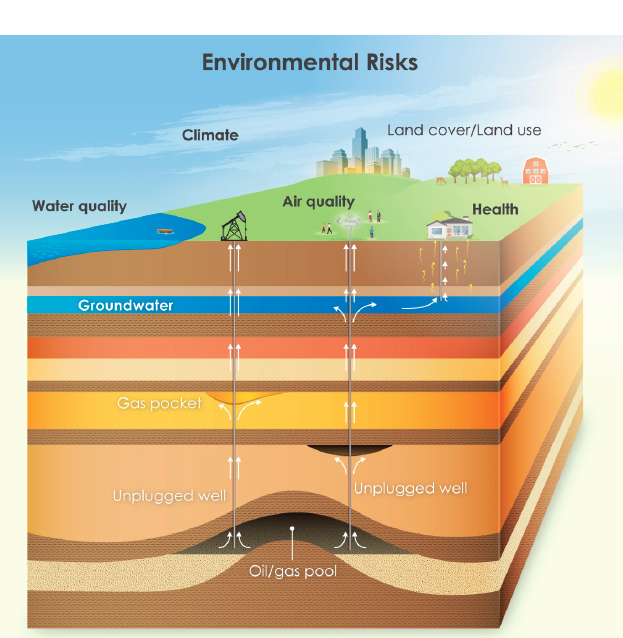

The fourth session of the workshop, moderated by workshop planning committee member Mary Kang, McGill University, discussed both the environmental risks posed by leaking wells and opportunities for monitoring to mitigate related issues. She indicated that although the actual counts remain highly uncertain as wells continue to be documented, ~400,000 “nonproducing” oil and gas wells are located in Canada, and ~4 million nonproducing oil and gas wells are located in the United States. Orphaned wells comprise a subset of these nonproducing wells. Given the high number of wells, she said that managing and monitoring associated environmental risks is critical. When wells remain unplugged, fluids can migrate through pathways and affect both groundwater and air quality (see Figure 5-1), while risks of explosion also present safety concerns.

Kang noted that emissions of methane are of particular concern. Boutot and colleagues (2022) found that 123,318 documented orphaned wells had methane emissions that comprised 5–6% of total methane emissions from all abandoned wells in the United States. She explained, however, that uncertainties about methane emissions persist because the total number of wells remains unknown, and unmeasured or undetected high-emitting nonproducing wells likely exist. Many well attributes could contribute to the amount of methane released; for instance, some studies have captured data that suggest that well depth and age influence methane emissions. Thus far, however, she said that the only consistent contributing factor across methane studies is geographical area.

Kang remarked that isolating individual contributing factors is difficult because methane emission rates are driven by multiple processes. For example, when measuring methane emissions from the surface casing vent and from the wellhead separately, different trends are observed. She described a surface casing vent flow and gas migration dataset in Alberta that provides information about well integrity, but upon conducting

SOURCE: Kang, 2024 (modified from Kang et al., 2023).

measurements, 68% of what her team found was not included in this dataset (Bowman et al., 2023). She stressed, however, that this difference likely is due to temporal variability.

Moving from a discussion of methane emissions to groundwater contamination, Kang noted that groundwater typically moves slowly, and different types of contaminants exist (e.g., some dissolve in water, but others do not). Cleaning up contaminated groundwater is both difficult and expensive.1 She explained that the average groundwater well depth in the United States is ~230 feet, while oil and gas wells might have a depth of a few thousand feet (Perrone and Jasechko, 2017). However, groundwater wells are now being drilled deeper, and what constitutes “protected waters” might need to be redefined.

Before the first presentation of the session began, Kang invited speakers to consider the following questions: How confident are we with national estimates of orphaned and abandoned well methane emissions? Can methane emissions be used as a proxy for other environmental impacts? Can we use well attributes to identify potentially

___________________

1 For more information on groundwater, see https://www.epa.gov/superfund/superfund-groundwater-introduction#:~:text=When%20contaminated%20oil%20or%20chemical,contaminated%20by%20the%20polluted%20groundwater.

high-emitting wells? How can we identify and remediate groundwater contamination? Where are the data and data management gaps, and how can new technologies be used to address them?

THE ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY AND THE QUANTIFICATION OF METHANE FROM WELLS

Sarah Busch, Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), provided an overview of the greenhouse gas (GHG) data that EPA is collecting on abandoned wells. She explained that EPA’s Inventory of U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks (GHGI)2 and GHG Reporting Program (GHGRP)3 are complementary programs, as the latter provides key input to the former. The GHGI includes a “holistic” estimate of emissions and sinks across all sectors of the U.S. economy, including a category on abandoned oil and gas wells; the GHGRP collects emissions data only from large GHG-emitting facilities in the United States.

Busch first outlined the GHGI’s multipronged classification of “abandoned wells.” Abandoned wells include (1) wells that are not plugged but have no recent production (i.e., idle, inactive, temporarily abandoned, dormant, shut-in), (2) wells with no recent production and no responsible operator (i.e., orphaned, abandoned, deserted, long-term idle), and (3) wells that have been plugged. The GHGI’s estimate is based on ~3.9 million wells, ~3 million of which are oil wells; orphaned wells comprise a subset of these wells, but the GHGI does not include a specific estimate of orphaned well count. She noted that over the past 30 years, the overall count of abandoned oil and gas wells has increased significantly, which corresponds to an increase in carbon dioxide and methane emissions.

Busch explained that EPA developed methane emission factors at both the national level and specifically for the Appalachian region using data from Kang and colleagues (2016) and Townsend-Small and colleagues (2016). Well counts were calculated using Enverus data to determine the fraction of plugged to unplugged abandoned wells. EPA then developed state-level annual counts of abandoned wells for 1990–2022 by summing an annual estimate of abandoned wells in the Enverus dataset and an estimate of wells not in that dataset (i.e., from historical records from state agencies and the U.S. Geological Survey). She noted that EPA continues to assess new data and feedback on how to improve the abandoned oil and gas well emissions and activity data, and the GHGI will be updated as new information becomes available. For example, several new data sources are under development, including the Department of the Interior’s (DOI’s) orphaned well database, the National Energy Technology Laboratory’s (NETL’s) marginal conventional well database, and Subpart W4 data improvements. She indicated that Subpart W focuses specifically on the wells from large-producing facilities—that

___________________

2 For more information on the GHGI, see https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/inventory-us-greenhouse-gas-emissions-and-sinks.

3 For more information on the GHGRP, see https://www.epa.gov/ghgreporting.

4 Subpart W refers to the reporting requirements for wells for petroleum and natural gas systems (40 CFR Part 98, Subpart W), see https://www.epa.gov/ghgreporting/rulemaking-notices-ghg-reporting.

is, greater than 25,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent, or about 50% of the producing wells in the United States. Beginning in 2025, she added, EPA will begin collecting more well-level estimates of pre-plugging emissions.

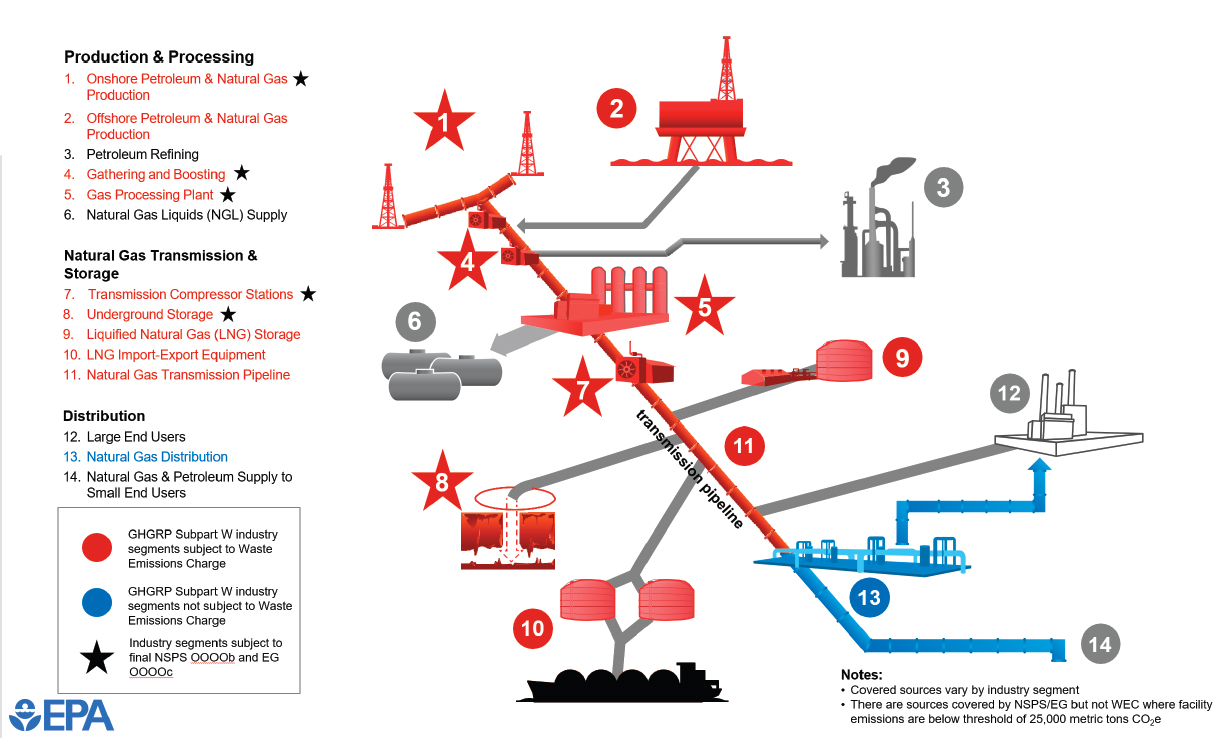

Busch next commented on three EPA regulations, not all of which have been finalized (see Figure 5-2). In particular, EPA will collect information on wells in the onshore petroleum and natural gas production sector, in the offshore petroleum and natural gas production sector, and in the underground storage sector.

She conveyed that information on well emissions from onshore production can be collected in several ways, such as via measurement and/or engineering calculations from equipment leaks, well venting for liquids unloading, and completions and workovers with and without hydraulic fracturing. To gather insight into well emissions from offshore production, data and quantification methods from the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management’s Outer Continental Shelf Emissions Inventory are used. This year, Subpart W will collect information on the quantity of natural gas and crude oil and condensate sent to sale for each permanently shut-in or plugged well. For underground storage wells, well-level information is not available, but facility-level equipment leak emissions information will be categorized (e.g., by storage wellhead).

Busch explained that Subpart W was updated in response to new authorities under the Clean Air Act (Section 136) to reduce methane emissions from oil and gas via the Methane Emissions Reduction Program. These new authorities included creating an incentive program for financial and technical assistance. Accordingly, NETL developed the Methane Measurement Guidelines for Marginal Conventional Wells.5 Marginal wells are defined as those that produce less than or equal to 15 barrels of oil equivalent per day over the prior 12-month period; the minimum detection limit is less than 100 grams/hour. To quantify pre-plugging emissions, a sample could be taken directly from the well using high-flow sampling with flux chambers or bag sampling, or field measurements using drones or ground-based vehicles described in EPA OTM 33A. She added that remote sensing could be used in the future but only if it could achieve the minimum detection limit. Post-measurement requirements are detection-based only, she suggested the use of EPA Method 21 or OGI in this case. She noted that this is the minimum data reporting requirements; however, other data reporting is encouraged.

Busch pointed out that these new authorities under the Clean Air Act also included establishing the Waste Emissions Charge,6 which was proposed in January 2024 but from which some wells would be exempt. EPA proposed to exempt emissions from wells that are permanently shut-in or plugged in accordance with all applicable closure requirements, and the exempted emissions are limited to wellhead emissions (i.e., leaks, liquids unloading, and workovers).

___________________

5 The guidelines are available at https://netl.doe.gov/methane-emissions-reduction-program.

6 For more information about the Waste Emissions Charge, see https://www.epa.gov/inflation-reduction-act/waste-emissions-charge.

SOURCE: Environmental Protection Agency, 2024.

POTENTIAL METHODS FOR QUANTIFYING METHANE EMISSIONS FROM ABANDONED OIL AND GAS WELLS

James France, Environmental Defense Fund, explained that when trying to measure methane, the environments of the measurement regions might vary significantly. In some cases, the location is unknown. However, when the location is known, questions arise about whether single wells, multiple wells, or large clusters of wells need to be quantified; if getting close to the infrastructure is feasible; if one has a clear line of sight; and whether changeable weather conditions could create issues.

France indicated that for isolated infrastructure in remote locations with difficult and variable terrain, bespoke chamber methods are useful to measure methane emissions. However, he said that different environments dictate different measurement methodologies. For example, Azerbaijan has semi-active infrastructure and redundant infrastructure together, so a very different measurement approach would be used. He suggested choosing a quantification methodology based on the scale of the environment. For instance, component-level methods to detect emission (e.g., high-flow sample bagging and an optical gas imaging camera) are appropriate to quantify known leaks that can be visualized or measured directly. At the facility level, where a cluster of infrastructure might exist, downwind methodologies (e.g., open-path measurements) might be useful to capture a full plume or a subsection of a plume. He noted that these types of methodologies are useful in generating a total quantification measurement and for monitoring long-term emissions trends but will not pinpoint exact locations for mitigation. At the basin level, methodologies include the use of satellites and aircraft; however, information about the sources of the emissions is limited with these methodologies. He proposed that principles from facility-level quantification could be applied at the component level. Providing an example of using a Lagrangian dispersion model to help understand the expected emissions from an isolated abandoned well infrastructure, he suggested that open-path methods rather than direct measurements could be viable solutions with the right technologies.

France next provided a brief overview of five specific methodologies that could be used to measure methane emissions from abandoned oil and gas infrastructure in the future, starting with the most precise and the most expensive option. First, he described bespoke chamber systems as the “gold standard” for abandoned well quantification. Using these systems, one can isolate the emissions source completely, and the method is usually reliable and not influenced by other local sources. However, he noted that this method is time-consuming and expensive and often requires custom fabrication. Simpler off-the-shelf options (e.g., a high-flow sampler) could be appropriate in some situations, but then many emissions might not be detectable. Second, he then noted that in a few years, a small-scale eddy covariance system may provide quantification over several sites a day as a single-person set-up. However, he cautioned that these systems are difficult to install because they require consideration of the terrain and the footprint of the source, are scientifically challenging to use, have expensive instrument costs, and require a separate screening method. Third, he noted that EPA’s Other Test Method 33A, which is being used to quantify downwind plumes from industrial sources, could be adapted for abandoned oil and gas infrastructure with modern, highly portable parts per billion–level precision instrumentation. This instrumentation is also expensive but

could collect sufficient data in 30 minutes using an open-path methodology. Emission rates would still have medium-to-large uncertainties, he continued, but a deluxe edition could release tracer gas at the same point as the emission source to eliminate any questions about the influence of the wind. Fourth, he explained that quantified optical gas imaging systems are straightforward to use and allow for screening, localization, and quantification in a single visit with a single instrument. The systems do not offer robust quantification, though, owing in part to interference issues. Fifth, he indicated that open-path tunable diode laser absorption spectroscopy (TDLAS) currently is the only remote sensing option for abandoned wells. Drone-mounted TDLAS could screen for the largest emitters, especially when combined with magnetometry surveys. Limited literature is available on their effectiveness; although these systems are not very precise, he mentioned that their best potential is for large-scale emission detection and for methane mitigation planning.

Before concluding his presentation, France presented a brief overview of available sensors. Laser cavity systems, which are not yet widespread in industry, could be useful if open-path measurements are used more often. These systems are very precise (with an accuracy of 1 ppb in atmospheric methane) but very expensive (at least $20,000–$30,000). Less expensive, smaller options that can be mounted on drones are also emerging. He added that commercial metal oxide sensors could be useful for long-term monitoring if attached directly to infrastructure. He reiterated that although the bespoke chamber system remains the gold standard for quantification, for cost-effective “bucketing” of emissions for mitigation planning and calculating generalized emission distributions, open-path options are viable and hopefully will continue to improve as technology and platforms progress.

METHANE EMISSIONS AND WATER QUALITY IMPACTS AROUND ORPHANED AND ABANDONED HYDROCARBON WELLS

Susan Brantley, Pennsylvania State University, noted that DOI is asking each recipient of an Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) grant to (1) document the methodologies that the state will use to measure and track groundwater and surface water contamination related to orphaned wells, including how it will assess the effectiveness of plugging to address this contamination; and (2) document both pre- and post-plugging values of gaseous emissions and water contamination.

To assess the effectiveness of plugging, Brantley suggested first considering at what point water can best be sampled and analyzed to measure and track contamination, and by whom. Proving that plugging a well fixed a particular problem is difficult, she explained, owing to a variety in sources of contamination and seasonal changes. Therefore, several lines of evidence—water chemistry, gas chemistry and isotopes, pump tests, three-dimensional geologic mapping, geochemical modeling, and hydrological modeling—would better attribute causation. She indicated that the “gold standard” is to collect timeline data both before and after plugging a well, with professional hydrogeologists and certified laboratories conducting all sampling and analysis activities.

Brantley stated that the second step in assessing the effectiveness of plugging is to determine what could be chemically analyzed in the water—for example, gases, salt

cations and anions, and/or metals and toxic species. In other words, one would determine which primary contaminants are released by modern or legacy oil and gas wells. She mentioned that as of 2023, 50% of the Pennsylvania Water Supply Determination Letters cited methane release, indicating that this is a problem caused by shale gas well development. However, many sources of methane are unrelated to oil and gas—for example, biogenic gas; landfills; or thermogenic gas, which often emits naturally from fractured shale. She explained that documenting that the methane is actually from a leaking well often requires analyzing isotopes and ethane, which is a very expensive and non-definitive process. Another key issue to consider when determining what could be chemically analyzed in the water relates to the secondary contaminants that are emitted from the subsurface rock when the primary contaminants are released. For example, when methane leaks from a borehole, secondary contaminants can be discharged. The methane can be oxidized and coupled by bacteria to reduction of sulfate; when sulfate is reduced, it becomes hydrogen sulfide—a toxic gas. Methane also can be oxidized to carbon dioxide at the same time that iron oxides are reduced to iron(II); therefore, she continued, many iron oxides are present in the subsurface and often contain other metals (e.g., arsenic) that can be released into solution at the same time and be considered secondary contaminants.

Brantley noted that after methane, the second most frequently identified contaminant group from shale gas in the Pennsylvania Water Supply Determination Letters includes iron, manganese, and turbidity. She observed that distinguishing contaminants from natural iron and manganese is difficult, reinforcing the value of collecting data both before and after plugging to make a determination. The third, most commonly identified contaminant group includes salt species in oilfield brines, because large volumes of salty water come up with the oil and gas. Thus, she explained that seeing high total-dissolved solids, chloride, and barium is common in shale gas regions. However, as in the previous case, other sources exist such as road salts, naturally upwelling brine, and non-oil and non-gas pollution; to determine whether brine has impacted a water sample, one can use ratios of indicator elements such as chloride or bromide (Woda et al., 2018). She added that considering what is in these brines is worthwhile. Brines in different basins across the United States differ; for example, the Marcellus in Pennsylvania has some of the saltiest water. In addition to sodium chloride and indicator elements, it could include organics, toxic elements, and radium (Barbot et al., 2013; Rowan et al., 2011).

Because some toxic elements might be elevated slightly in concentration, Brantley continued, another important issue to consider when determining what could be chemically analyzed in the water relates to identifying toxic species for local residents. Using a back-of-the-envelope calculation to determine the chloride concentration in drinking water if the water were contaminated by this “average Pennsylvania brine” and assuming that each metal reached EPA’s maximum contamination limit, Shaheen and colleagues (2022) found that some of the toxic elements reached concentrations at which the person drinking the water would not taste the salt.

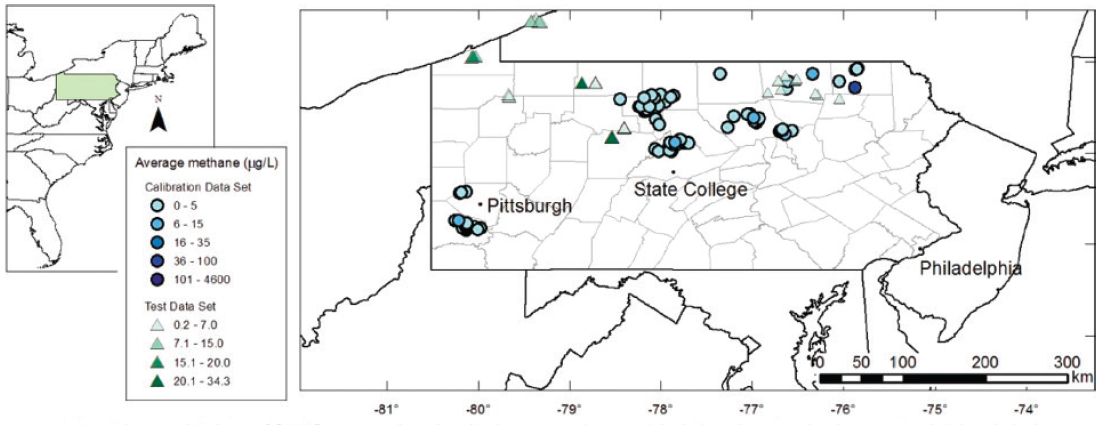

Brantley remarked that in the third step of assessing the effectiveness of plugging, one chooses where water would be sampled. She referenced a study on the potential use of surface water to detect methane contamination from oil and gas wells (Wendt et al., 2018; see Figure 5-3). Samples were collected at 131 sites across the northern

SOURCE: Wendt et al., 2018.

Appalachian Basin; 470 of 479 surface samples were supersaturated with respect to methane in the atmosphere. The study suggested that for non-wetland sites, concentrations above 4 g CH4/L could be from a leaking gas well, shallow organic-rich shale, coal releases, or a landfill. The study found that 12 of 41 non-wetland sites near active, plugged, orphaned, or abandoned oil and gas wells were above this threshold of 4 g CH4/L. The study thus points to surface waters as evidence of methane migration from leaking wells; however, she suggested that wetlands and other types of sites like landfills be avoided, and dilution usually hides contamination.

Moving from a discussion of sampling surface water to sampling groundwater, Brantley explained that in some terrains, contaminants are not observed in groundwater close to the source; instead, they are observed 1–2 km in the distance owing to subsurface fracturing, faults, and folding. She added that geology is complicated in terms of finding connections between a source and contamination. In another example, she indicated that homeowner wells located 1–3 km from shale gas wells were found to be contaminated with methane and an aqueous pollutant—one of the farthest documented distances of migration of contamination associated with a shale gas well (Llewellyn et al., 2015). Therefore, she suggested sampling water from drinking water wells and surface waters within 1–3 km, preferably downgradient and at the same or lower elevations as a legacy well.

LEVERAGING PUBLICLY AVAILABLE DATA TO UNDERSTAND WELL-INTEGRITY RISKS

Greg Lackey, NETL, provided an overview of a multiyear effort to analyze large datasets to understand well-integrity risks. He first explained that when aggregating state plugging prioritization systems, he and his colleagues found that a well’s distance to a sensitive receptor is the highest priority, followed by a well’s leaking status. Although a leak can be caused by a well-integrity issue, especially in older undocumented wells, he pointed out that integrity issues do not always result in an emission of gas. He noted that with nearly 150,000 documented orphaned wells in the United States, conducting inspections and collecting measurements from each well to inform prioritization efforts is not currently possible.

However, Lackey commented that data from well-integrity monitoring programs provide insight into leakage. He said that leaks in wells begin with a source and a leakage pathway, which varies based on well construction. The pathway could be to the surface, to groundwater, or to the atmosphere. For example, the source of a leak could be an over-pressured zone, and the leakage pathway to the surface could be from an uncemented portion of the annulus, a micro-annulus, gas channels, fractures, or a casing leak. Pathways to groundwater include a fault or preferential pathway along the wellbore into which gas migrating upward can escape. For example, in Colorado, some areas have had sustained casing pressure that has built up so much that it has displaced fluid from the surface casing. He emphasized that this evidence demonstrates the value of monitoring for sustained casing pressure specifically and of developing well-integrity monitoring programs more generally. In terms of pathways to the atmosphere, he noted

that if annuli are left open, fluids that are transmitted into the wellbore will escape into the atmosphere. Other pathways to the atmosphere include faulty fittings on a wellhead that could transmit production gas.

Lackey next described results from a 2021 study that aggregated testing data from Pennsylvania, Colorado, and New Mexico. These data were analyzed based on American Petroleum Institute (API)’s protocol to interpret annular pressures and diagnose sustained casing pressure (Lackey et al., 2021). The study found that the frequency of integrity issues among wells varies widely across regions—for example, in Colorado, integrity issues occurred in 0.3–26.5% of the wells, depending on the basin. Since Colorado began requiring testing for all wells, the 26.5% has decreased to 17.1%. He explained that other case studies have highlighted the varying causes of integrity issues in different regions. For example, in an area of Alberta with a cluster of integrity issues, the majority of surface casing annuli were found to have mostly intermediate gas (Szatkowski et al., 2002). In a study of wells in Colorado, the gas isotopically matched the production gas, with the cement top above that zone, in ~70% of the ~2,000 wells analyzed (Lackey et al., 2022). He indicated that these wells likely had micro-annuli that were causing sustained casing pressure.

Lackey specified that for large datasets like those used in the previous case studies, machine learning models can help to make useful predictions about integrity issues and provide insight into the drivers of integrity issues. Classification models are particularly effective in screening for wells that may have sustained casing pressure or casing vent flow. However, these models cannot yet predict the magnitude of such issues, and they might provide conflicting information. Yet, he said that the fact that causes of leaks vary between studies is expected given the variation in well types, sources of leaks, and leakage pathways.

Lackey also mentioned that in these modern datasets, the relationship between well age and leakage is often reversed, in part because more integrity issues are observed in newer horizontal and directional wells and because the datasets are biased toward newer wells with owners. Furthermore, he noted that well-integrity issues tend to be spatially clustered, given that geology varies by location and wells are designed for specific geologies (Bachu, 2017; Sandl et al., 2021). Therefore, if the specific geology can amplify clustering and frequency of integrity issues, he said that well-integrity monitoring programs are especially helpful in identifying “hotspot” areas for sustained casing pressure. He added that because wells near one another are likely to be similar and because leaking wells could transmit fluids to nearby wells, modeling based on spatial clustering to predict leak potential could be valuable for prioritizing the inspection of orphaned wells, especially when minimal information is available on the wells themselves beyond their location (Lackey et al., 2024).

Lackey remarked that whether the lessons learned from these large datasets of newer wells apply to older orphaned wells remains to be seen. With DOI’s Orphaned Wells Program, an opportunity exists to collect emissions measurements from orphaned wells and to determine whether they were leaking when they were abandoned. He highlighted the importance of aggregating these data (as well as data from wells without emissions) to better understand well integrity and well leakage. For example, in a

recent study conducted by the U.S. Geological Survey, emissions measurements were aggregated to reveal that high emissions are being found in wells located in thermogenic gas reservoirs (Gianoutsos et al., 2024). The Department of Energy (DOE) also is contributing to this goal to leverage data by developing methods to better document and characterize orphaned wells (including by creating tools to digitize records and synthesize multiple forms of data) and by developing noninvasive well-characterization techniques.

Lackey underscored the value of continuing to collaborate with the states to synthesize well data (e.g., compliance inspection data) with other information. Furthermore, he pointed out that all of this information also could be useful for those in other industries working to understand legacy well leakage risks before using the subsurface for other purposes in the future.

INFORMING GROUNDWATER-QUALITY MONITORING WITH MODELS

James Saiers, Yale University, observed that although groundwater quality monitoring is critical to protecting aquifers and human health, it is expensive and rarely used to assess contamination from orphaned wells. For groundwater monitoring around orphaned wells to become practical, he said that measurements would target areas with the greatest vulnerability to contamination. Thus, he presented a vulnerability framework that could inform the design of groundwater monitoring plans to evaluate the impacts of orphaned wells.

Saiers first provided a definition of vulnerability: the probability of drinking water impairment at a receptor location (e.g., a household drinking water well) in the event of a contaminant release from a source (e.g., a leaking orphaned well). He explained that when contaminants are released from a source, they do not move randomly; rather, they move in a preferred direction according to physical flow and transport processes. Therefore, vulnerability depends on the spatial relationship between sources and receptors as well as groundwater flow patterns and rates.

Saiers indicated that vulnerability can be estimated with hydrologic models. Model-based vulnerability assessments can help address the following questions related to groundwater quality monitoring around orphaned wells: (1) Which domestic water wells are most likely to be affected by orphaned well contamination? (2) When will contamination from orphaned wells likely be detected at water supply levels? (3) Where can monitoring wells be installed to detect and characterize contamination from orphaned wells?

Saiers elaborated on this concept of the vulnerability framework by providing examples from studies conducted in the Appalachian Basin, which considered the vulnerability of residential drinking water supplies to wastewater spills. Although the source of contamination in these examples was an unconventional oil and gas well pad (Soriano et al., 2020), he pointed out that a similar analysis could be done with orphaned wells as the source of contamination. The first step in this watershed-level vulnerability assessment was to develop and calibrate a groundwater flow model to predict the distri-

bution in hydraulic heads or groundwater levels. Groundwater flow patterns then could be deduced, and contaminant migration could be simulated. He indicated that this model was calibrated by identifying an ensemble of simulations that allowed flow model predictions to match groundwater discharges to stream and measured aquifer water levels. Two thousand realizations were run with this model to best assess the uncertainty in the model parameterization on groundwater flow (Soriano et al., 2020, 2022).

Once the groundwater flow model was created, Saiers noted that the next step was to couple that model’s output with a particle tracking model. Virtual particles were injected at the well pad, and their trajectory was followed as they moved through the groundwater flow system. These particle tracks indicated where and how far the contaminant might travel based on groundwater flow. He said that this particle tracking simulation was conducted 2,000 times (for each realization of the groundwater flow model) and produced 2,000 hydrologically possible trajectories for contaminant migration away from the well pad (Soriano et al., 2020, 2022).

The following step, Saiers continued, was to use these particle tracks to estimate vulnerability. Vulnerability was defined, for each grid cell in the model domain, as the number of simulations in which a particle track intersected with the grid cell out of the total number of realizations. He explained that vulnerability ranges from 0 to 1; higher values indicate greater agreement among the realizations that a grid cell falls on an advective transport path from the well pad (Soriano et al., 2020, 2022). For a particular snapshot in time, the vulnerability predictions revealed which areas might be impacted if a contaminant was released from a well pad. He pointed out that the vulnerability plumes were not all oriented in the same way, which reflects the roles of topography, geology, and the stream river network in creating complex groundwater flow patterns.

Consequently, Saiers noted that the next phases of the vulnerability assessment were to scale up from the watershed level to all of Bradford County, Pennsylvania as well as to compare the vulnerability estimates to actual measurements of drinking water quality. Ninety-one samples of drinking water were collected; the use of elemental ratios helped to distinguish non-impacted groundwater from water that had been influenced by inputs of produced water. Many samples that appeared to be vulnerable to contamination were not actually impacted, which was expected given that spills on well pads are fairly rare. Furthermore, six of eight samples from the shale gas produced water region were from groundwater wells identified as being vulnerable, which suggested that a link might exist between spills at well sites and contamination. He and his team then looked for written records of spills near vulnerable domestic wells impaired by produced water signatures: five of the six vulnerable wells were near well pads where spills had been recorded.

With this information, Saiers and his team modified the vulnerability approach so that it could scale further. It was applied to a large region across Ohio, West Virginia, and Pennsylvania, where ~10,000 wells had been drilled into the Marcellus and Utica shale and where 1.5 million people rely on private water wells for their drinking water. Their analysis predicted that 4% of this region is vulnerable to contamination from unconventional oil and gas, which includes ~2% of the population, although the vul-

nerability is distributed unevenly (Soriano et al., 2022). He noted that these vulnerable areas thus could be monitored when concerns about contamination arise.

In closing, Saiers emphasized that monitoring cannot be conducted everywhere owing to high costs and limited accessibility. This vulnerability framework can be used to optimize locations for groundwater sampling and to characterize the extent of contamination in a cost-effective way; to identify domestic wells of greatest risk for targeted monitoring and preventative action; and to support contaminant-source attribution analyses. He underscored that vulnerability analyses can be conducted with free, public domain software (e.g., MODFLOW, MODPATH)7 and by professionals employed in consulting firms and governmental scientific and regulatory agencies.

OPEN DISCUSSION

Kang moderated a discussion among the workshop speakers and participants. A participant observed the significant spread on the particle tracking in Saiers’s models and asked if additional measurements and conditioning data would narrow the range of potentially affected areas. Saiers indicated that the spread reflects uncertainty, but having more data to characterize the hydraulic conductivity field could reduce this uncertainty. He added that because the plumes exclude a significant area, one knows where not to spend time monitoring.

An online participant posed a question about whether North American plugging and monitoring best practices are transferable to other extractive industries and to other continents. Kang replied that although they are transferable to some extent, additional studies could confirm how transferable. France added that much insight can transfer, especially in terms of the methodologies used for emissions monitoring; however, different countries have different regulatory environments and different practices to consider. Brantley elaborated that geology also varies by location. She provided an example based on a study of fugitive methane incidents related to shale gas development in the southwest and northeast areas of Pennsylvania. The methane incidents were higher in the northeast than in the southwest, where much of the intermediate-depth gas had already been extracted. Thus, in addition to understanding the geology of a particular area, she said that it is important to understand legacy extraction activities.

Dwayne Purvis, Purvis Energy Advisors, asked if different standards are needed for decommissioning to prevent leaks from shale wells that will repressurize over years to decades. Lackey responded that data from the long-term monitoring of plugged wells could address this question. Workshop planning committee member Nathan Meehan, Texas A&M University, pointed out that if significant active migration occurs in producing wells, the problem likely will persist in abandoned wells, and he suggested that an alternate approach for the repair and plugging may be needed. Lackey added that some states that conduct integrity monitoring require operators to repair annular problems. He agreed that knowing which wells have these problems is critically important and proposed that remediation efforts occur prior to abandonment, but that is not clear in all jurisdictions’ requirements.

___________________

7 More information on MODFLOW can be found at https://www.usgs.gov/mission-areas/water-resources/science/modflow-and-related-programs.

Kang invited state leaders to share their perspectives on methane monitoring and groundwater modeling approaches. Michael Hickey, Colorado Energy and Carbon Management Commission, emphasized that oil and gas systems involve much more than just a well. For example, gas could emerge in a field 1 mile from a well or a tank battery owing to a leak in a flow line. Another issue is that wells do not flow uniformly; they surge. Therefore, he said that how long to monitor wells remains a very difficult question. Lackey noted that he and his team are expanding their models to include the whole well pad, and Busch reflected on the potential for improvements in Subpart W as well as the value of capturing more emissions data.

Bryan McLellan, Alaska Oil and Gas Conservation Commission, expressed his interest in evaluating the effectiveness of Alaska’s plugging program and wondered if a simple, low-cost method exists to screen wells that have been plugged and abandoned. Kang replied that DOE is developing useful tools, and Lackey highlighted the FAST (Dubey et al., 2024) method as a low-cost way to measure emissions. However, he said that such a method, which focuses on emissions sources from the wellhead or an open hole, might not be appropriate if the goal is to verify already-plugged wells. McLellan inquired specifically about the use of remote sensing techniques, and Kang explained that drones might detect methane emissions to the atmosphere but might not be useful to detect subsurface impacts. France added that TDLAS has great potential to screen for very potent leaks; however, a higher-precision instrument could detect lower volumes of methane. Brantley remarked that collecting and analyzing samples is very expensive. She suggested instead spending federal funds on plugging wells and then conducting simple screening for methane. Hickey encouraged the use of soil gas sampling, which is a fairly straightforward and effective methane detection method being used at the county level in Colorado. Kang then asked about the use of saturated and unsaturated coupled models. Saiers explained that those multiphase flow models are critical if one is interested in the dissolved and gaseous states of methane, but they are difficult to scale and require greater characterization than single-phase flow models. Multiphase flow models could guide one where to look for methane, he continued, but measurements would still be needed for verification.

Don Hegburg, Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection, commented that the vulnerability framework presented by Saiers could be used to assist with well-plugging prioritization. He cautioned that when water supplies are sampled, they likely will exceed some standards because water supplies inherently are not well maintained; drinking water wells are subject to surface contamination that is not caused by oil and gas. Before allocating a significant amount of funding toward sampling, he suggested first conducting a basic geochemistry analysis or checking for high-conductivity subsurface areas around a well site.

Danny Sorrells, Railroad Commission of Texas (RRC), remarked that 8,674 orphaned wells are found across 10 districts in Texas. Each district has at least two forward-looking infrared cameras that check those wells regularly for leaks. Furthermore, all 180 of the RRC’s oil and gas inspectors carry salinity meters and can check nearby creeks immediately for pollution. Brantley pointed out that groundwater data are

difficult to obtain. She praised Pennsylvania, Colorado, and Texas for widely distributing their groundwater data and encouraged more states to put their data online so that the public can be better protected. Eric van Oort, University of Texas at Austin, remarked on the work on large datasets that Lackey presented, which could be useful both to prioritize wells for permanent abandonment and to locate wells with good integrity that could be reused and reprioritized. He proposed that academia and governmental organizations collaborate to entice operators to share more of their data to further this work. He also mentioned work at Heriot-Watt University on probabilistic modeling, which could allow projections about which wells are likely to leak and at what severity. He said that adding this approach could help develop a tool to assist with future forecasting.