Electricity System Operability and Reliability Under Increasing Complexity: Proceedings of a Workshop (2025)

Chapter: 5 Regulating a Complex Electricity System with Increasing Distributed Energy Resources

5

Regulating a Complex Electricity System with Increasing Distributed Energy Resources

Janet Gail Besser, moderator, New England Electricity Restructuring Roundtable, introduced and moderated a panel on regulatory approaches. In her introductory remarks, Besser highlighted several findings from The Role of Net Metering in the Evolving Electricity System, the 2023 National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s consensus study of which she was the committee chair (NASEM 2023). Distributed energy resource (DER) regulation has historically focused on compensation arrangements and incentives to encourage clean energy adoption. However, she noted that regulatory strategies that were appropriate when DER deployment was low may not be as necessary or effective when deployment becomes more widespread, and indeed some older regulations may become untenably expensive at larger scales. At the same time, there are new gaps and challenges emerging as grid operators grapple with increased loads and DER integration. As the grid continues to evolve, regulators will need to continue to review and approve new investment and compensation packages to ensure that they provide the widest and most equitable benefits for all customers. Besser emphasized that new and effective regulation will require creative thinking, thoughtful consideration of multiple perspectives, and an emphasis on technologies that will be used and useful.

PANEL PRESENTATIONS

Before turning to panelists for their opening comments, Besser stressed that “understanding where other people are coming from can help you

to move forward.” To provide a forum for expressing different perspectives on regulation relevant to DER adoption and integration, the session featured panelists from diverse backgrounds who examined the complex issues that utilities, customers, and regulators face along with solutions that are being explored.

The Complexities of Shared Regulation of Distributed Energy Resources

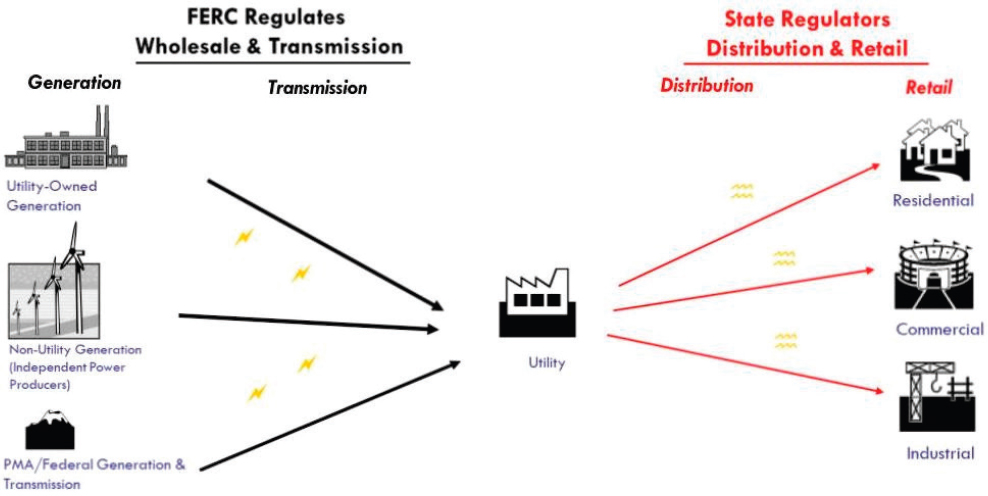

Ann E. Rendahl, commissioner, Washington Utilities and Transportation Commission, discussed the complexities and areas of friction that arise from a system in which regulation of DERs is shared among federal and state actors and highlighted the approaches being pursued in Washington State. For context, Rendahl explained that U.S. electric power systems are regulated by federal and state entities under the concept of “cooperative federalism” (see Figure 5-1). With regard to DER integration, she noted that the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) has issued several orders to remove barriers and enable DER aggregations to participate in organized markets. From some states’ perspectives, however, these orders have diminished state authority over retail programs, rates, benefits, and reliability.

In Washington State, which does not participate in a regional transmission organization (RTO), energy is provided by a mix of investor-owned utilities (IOUs) and consumer-owned utilities (COUs) of varying sizes. The commission does not regulate COUs. To improve DER monitoring and management, Washington IOUs are in the process of developing virtual power plants (VPPs), DER management systems, and new performance metrics. Multiple state laws and policies support DER aggregations and the Clean Energy Transformation Act (CETA) goal to achieve 100 percent clean energy for Washington customers by 2045.

Energy equity is an important part of Washington’s clean energy and statutory direction, and the commission is developing equity and energy justice policy statements that provide guidance to utilities and other regulated companies, as well as for the commission itself, regarding procedural, recognition, distributive, and restorative justice. In particular, the CETA requires utilities to ensure that all customers benefit equitably from the clean energy transition, with customer benefit indicators and specific targets for vulnerable populations and highly impacted communities. Utilities are also required to file multiyear rate plans, with frequent evaluations, including performance-based regulatory metrics and analyses to aid the commission’s evaluation of utility performance.

Rate increases, energy affordability, market participation, and cost recovery are also critical issues facing utilities and the commission in

NOTE: FERC = Federal Energy Regulatory Commission; PMA = Power Marketing Administration.

SOURCE: Rendahl (2024).

Washington. Rates are under pressure not only from DERs but also from costs associated with weather events such as wildfires in the western United States, the costs of implementing clean energy projects, and the costs of building out new transmission lines. In light of these issues, Rendahl said that there remain unresolved questions in Washington State, as in many states, with regard to DER integration, including whether DERs should be owned by the utilities or by consumers, and how customers should be compensated for participating in VPPs or demand-response programs.

Considering System Goals in System Design

Dede Subakti, vice president, system operations, California Independent System Operator (CAISO), highlighted additional complexities that California has encountered in making decisions about investments and system design for DER integration. Stating that “you get what you pay for and you get what you design,” he emphasized that it is important to recognize that regulations and systems will only accomplish what they are designed and equipped to accomplish.

In designing systems for DER integration, Subakti said it is useful to distinguish between resources that produce dispatchable energy, in

which energy generation can be controlled by operators, and those that produce nondispatchable energy, such as rooftop solar generation, which are often intermittent and cannot be controlled. The regulatory structures and compensation arrangements that are most appropriate for a given utility may depend on which types of resources the utility most wants to incentivize and integrate.

Dispatchable DERs are more versatile; they can act as a stand-alone resource, be combined or aggregated with others, or be used to reduce loads for demand response. They are also price-sensitive. CAISO was early to integrate dispatchable DERs and has established processes and models for stand-alone DERs and demand-response services. California has onboarded more than 500 new stand-alone DERs with a total generation of 2.2 gigawatts since 2005, and these are subject to the same requirements as transmission-connected resources. For dispatchable demand-response resources, the story is more complicated, with two major models (proxy demand-response and reliability demand-response resource) and seven different methods for setting payment structures. CAISO markets include 1.7 gigawatts of demand-response services.

DER aggregations (DERAs), which CAISO began supporting in 2016, have faced greater obstacles to adoption. CAISO allows DERs less than 1 megawatt in size to participate in DERAs, but requires special reviews to ensure that participating DERs are not receiving double compensation from both the wholesale and retail side. The requirements and systems to support DERAs are being adjusted in response to FERC Order No. 2222 (FERC 2024a), and Subakti noted that the biggest lift in terms of implementation is the creation of a heterogenous DERA model that can include demand response. Two main reasons why California has seen low interest in DERAs are that the state’s retail programs are more attractive than CAISO programs and have no capacity limit, and the state’s stand-alone DER resource requirements are low. If the barriers to participation as a stand-alone resource are low enough, Subakti noted, there is no reason for DER owners to join DERAs.

Integration of nondispatchable energy sources, such as rooftop solar power, poses a different set of complexities for grid operators. Because these resources can vary widely in their generation minute to minute, it is crucial to forecast loads and consumption to create situational awareness of behind-the-meter activity, both for the short term and to inform infrastructure planning decisions.

While grid operators and regulators plan for the future, Subakti emphasized the importance of effective communication among those who are working in different parts of the system, especially around establishing system goals. For example, a system might be designed to utilize DERs for everyday energy supply, to avoid system disruptions, to fill the

gap when there are system disruptions, or some combination of these goals, but each scenario entails a different type of setup and incentives.

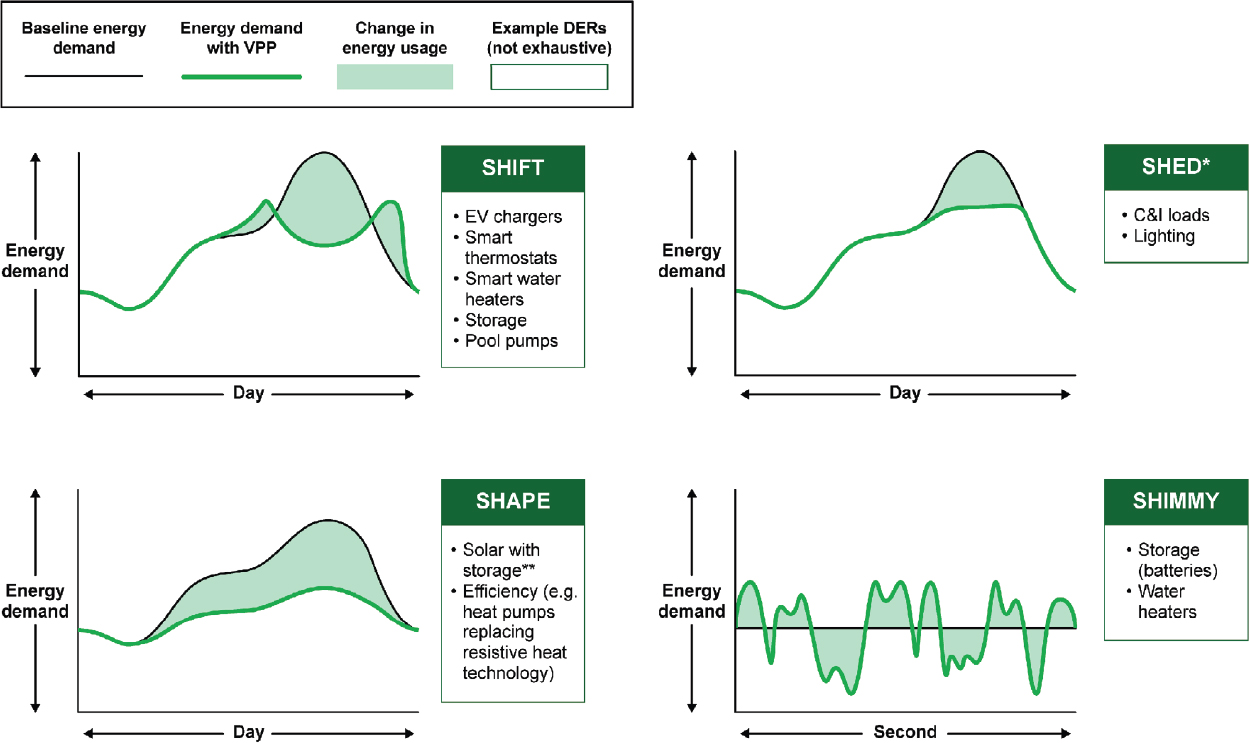

Regulatory Solutions for a Future High in Distributed Energy Resources

Ryan Katofsky, senior fellow, content and education, Advanced Energy United, provided context on the factors that are driving rapid changes in today’s energy markets and described tools and regulatory options for enabling a high-DER future. The main drivers of the current energy transition are technological improvements, customer preferences, and policy. Load growth and the retirement of fossil fuel–based resources are also contributors, although they can be seen as secondary drivers stemming from the main three. To illustrate the transitions that are under way, Katofsky highlighted data showing rapid increases in distributed solar paired with energy storage (Barbose et al. 2023), sales of electric vehicles (Alliance for Automotive Innovation 2024), and adoption of heat pumps (Takemura 2024). Against this backdrop, Katofsky cautioned that the grid will become unaffordable and unsustainable with “business-as-usual” approaches. Fortunately, innovation is rising to meet the need. For example, VPPs are providing value by helping to shape and reduce demand in different ways and provide grid services through technologies such as smart thermostats and water heaters and dynamic utilization of stored energy (in the form of electric vehicles (EVs) or behind-the-mater batteries) (Downing et al. 2023). Katofsky presented the potential value provided to the grid by VPPs through demand shaping by sharing the illustration shown in Figure 5-2.

DERs can bring unprecedented opportunity for demand flexibility at scale, but to fully realize this potential will require the appropriate regulatory frameworks. Katofsky said that regulatory frameworks need to support grid readiness for DER integration, align utility investments with a high-DER future, and leverage private investment for grid benefits. He noted,

Cost-of-service regulation—the basic utility business model that we have today—really limits opportunities for DERs, and this is because utilities are focused on deployment of capital in their networks … so that just sets them on a particular path. Some DERs can be supportive of that path, particularly around electrification, but others actually run counter to that model.

He suggested that new regulatory approaches will be required to realign utility financial incentives with desired outcomes and overcome challenges such as a lack of access to customer and system data

NOTES: * Load shed for some DERs results in load shifting to later hours as a system (e.g., HVAC) recovers from an event.

** Distributed solar with storage reduces demand on the grid without impacting the energy consumed behind the meter. C&I = commercial and industrial; DER = distributed energy resource; EV = electric vehicle; HVAC = heating, ventilation, and air conditioning; VPP = virtual power plant.

SOURCE: Downing et al. (2023).

for third-party DER companies and interconnection delays. Regulators and other decision makers also need to be mindful to not make abrupt changes to DER compensation mechanisms as they seek to establish these new approaches.

Katofsky outlined roles for utilities, customers, and third parties in supporting DER integration. Utilities act as platform providers and operators, DER enablers, and market operators, and can also be DER aggregators; customers are increasingly becoming engaged participants; and third parties provide DER solutions to customers, act as DER aggregators, and provide grid services to the utility. Foundational tools for enabling the high-DER future include proactive planning, comprehensive data access platforms, and various DER compensation mechanisms, including pricing (tariffs), programs (such as demand-response and VPP programs), and procurements (such as non-wires solutions). Katofsky described how these tools can be utilized in a variety of ways to suit different goals and markets. To align utility-focused financial incentives with desired policy outcomes, regulatory options can span a broad spectrum from tweaks to existing models, to more substantive changes to cost-of-service models, to fully reimagined business models (Cross-Call et al. 2018).

Incentive Regulation to Support Cost-Effective Integration of Distributed Energy Resources

David Brown, professor, Department of Economics, University of Alberta, described research insights that can help inform approaches to incentivizing utilities to integrate DERs in cost-effective ways. As other speakers had noted, conventional business models can sometimes create combative relationships between utilities and DERs. Because utilities are considered natural monopolies, they have historically been subject to cost-of-service regulation where the utility sets operating costs and the capital cost recovery and profits are determined by the utility but approved by the regulator. Existing investment and cost recovery structures have historically given utilities a preference for capital investment and a relatively limited incentive to innovate. Trends toward increased DER deployment and increased electrification can potentially reduce demand by providing new generation, provide demand response, or increase demand—for example, to support charging EVs. The result of this from the utility’s perspective is that DERs can simultaneously reduce demand for utility services while at the same time requiring new operational and infrastructure investments on the part of utilities, which often must be covered as part of operating costs rather than capital investments. This combination can create economic incentives for utilities to oppose DER integration, or at least undermines utilities’ incentive to innovate in order to best accommodate them.

Several pilot projects aimed at understanding the viability and cost effectiveness of dispatchable and nondispatchable DER loads (e.g., Fortis Alberta’s Electric Vehicle Smart Charging Pilot in partnership with Optiwatt) point to some financial incentives that can support successful DER integration. This research shows that there are multiple ways to leverage DERs for demand-side flexibility, and this can improve cost-effectiveness for utilities. One key finding is that automation greatly enhances demand response (increasing flexibility fivefold in one study), in particular in the context of managed EV charging.

Even as studies point to promising solutions, implementation challenges can remain, in part owing to the lack of a regulatory framework and short-term financial incentives for utilities to scale up the solutions that prove viable in pilots. To address this, Brown outlined how performance-based regulation and incentive-based regulation can help to align utilities’ business models with DER integration and deployment. As an example, he described how the Ontario Energy Board is piloting multiple incentive mechanisms—including a shared savings mechanism, a performance target or scorecard-based incentive, and allowing distributors to add a margin on payments to DER providers—to identify a business model that is in regulatory compliance, incentivizes DER integration, and creates savings and benefits for all stakeholders.

A Federal Perspective on Regulations for Integrating Distributed Energy Resources

Richard Glick, former FERC chair and principal at GQS New Energy Strategies, offered a federal perspective on DER integration regulation. Federal regulation does not apply to all DERs, as most are regulated at the retail level. The DERs that are most directly affected by federal regulation are those that participate in FERC-regulated wholesale markets. By encouraging or requiring RTOs to adopt changes to their rules that reduce barriers to DER deployment and integration, FERC Order No. 2222 was designed to facilitate DER integration across U.S. states that have RTOs.

While it is too early to determine whether Order No. 2222 has been successful in those goals, Glick described several challenges that have been encountered thus far, including lengthy implementation processes and the option for states to opt out of certain provisions, creating a patchwork effect with uneven penetration. DERs present unique challenges from a regulatory standpoint because they are comprised of different technologies, are in different locations, and can integrate into different RTOs. Complexities related to the size and telemetry requirements for regulated systems, interconnection delays, remaining areas of confusion over who is responsible for interconnections, and concerns about double compensation

at the wholesale and retail level have complicated integration efforts. Load forecasting presents another key challenge for utilities, as many other speakers mentioned, and Glick noted that forecasting is especially difficult when there is little behind-the-meter visibility.

DERs also create new opportunities. They are often cost effective for individual homes or businesses, can help to address load growth and weather concerns, reduce reliance on fossil fuels or new power plants, improve energy efficiency, and support electrification and decarbonization. For DER providers that are smaller in size, aggregation offers expanded opportunities to extract the greatest value from their DER investments while making DER integration easier to manage on the distribution side, Glick added.

PANEL DISCUSSION

Besser moderated a discussion among panelists covering financial incentives for innovation and DER integration; approaches to allocating costs among utilities, DER owners, and other customers; considerations for balancing utilities’ need for visibility with customer expectations of privacy, and the importance of attending to distribution-side issues.

Incentivizing Innovation

Panelists discussed options for incentivizing innovation to facilitate more effective DER integration. Katofsky stated that effective performance-based regulations can create financial motivation for utilities to support DERs and make related investments, aligning the interests of utilities and consumers for the benefit of the entire grid. For example, shared savings mechanisms enable utilities and customers to fairly share DER benefits such as the avoidance of costs associated with upgrading a substation. Rendahl noted that Washington State has experimented with shared savings models with some success. However, she added that one common issue is that much of the investment needed to support DER integration is software-based, which falls under operational costs rather than capital investments and is thus not subject to a utility’s authorized rate of return on capital. To address this, she suggested that regulations could be restructured to give utilities more options and the right set of incentives for cost recovery for such operational expenses. It was also noted that the National Association of Regulatory Utility Commissioners has a resolution that encourages state utility commissions to allow utilities to earn a rate of return, or to receive a form of incentive, for the use of cloud computing and software-as-a-service solutions (NARUC 2016).

Brown added that performance-incentive mechanisms, which set clear targets for utilities and are overlaid on top of performance-based regulations, can create effective financial incentives for utilities to implement DERs if they balance clear and achievable goals with cost offsets. Subatki agreed, suggesting that incentives can be tied to performance to encourage utilities to build FERC-compliant systems that avoid cascading negative effects and improve overall trust in the grid.

Utilities are primarily incentivized to make investments that lead to profit. Recognizing this, Glick said that FERC recently ordered utilities requesting permission to add transmission lines (a move that leads to greater profits for the utility under current regulatory structures) to demonstrate that they have thoroughly considered alternative options, such as grid-enhancing technologies (which do not require the same level of capital investment and thus do not contribute as much to profits). He suggested that this approach could be expanded to other areas such as energy resources and demand-response programs, to force utilities to explicitly justify investments that are not related to DER integration when DER integration strategies could help to address the same needs.

Besser asked panelists to comment on whether an entirely new regulatory framework would be preferable to incremental change. Katofsky replied that different states will have different approaches, but big changes require an enormous amount of effort. As a basic principle, he suggested that any new regulations should strive to support a competitive market. In line with this principle, for example, he said that utilities themselves, which have historically operated as monopolies, should not own behind-the-meter DERs because these currently exist in a competitive market. He reiterated that the most effective regulations will enable robust competition, create well-defined roles for each entity, and include appropriate financial motivations. Brown agreed, noting that the energy regulatory landscape is already very complex and that regulations should ideally be streamlined to leverage competitive markets without adding further complexity.

Considerations for Allocating Costs

Panelists discussed various considerations related to which parties bear the costs and benefits associated with DER integration. Katofsky stated that utilities may be more incentivized to make foundational DER integration investments if they can be recovered in rate cases. Rendahl noted that utility rate cases are an extremely complex process, and that utilities must submit supporting information to demonstrate that the investments are going to benefit customers, exactly how the technologies would be used, and what they would enable. She suggested that such

cases could also be strengthened if there are opportunities for technologies to simultaneously support DER integration and other goals that are important to the state, such as mitigating the impacts of wildfires.

Besser pointed out that FERC Order No. 2222 enables utilities to allocate the costs associated with DER integration more broadly than has previously been allowed. However, panelists noted that the idea of spreading DER-related costs more broadly has become contentious in some places. On one hand, it makes sense to spread the costs because DER integration offers benefits to the grid and society on the whole. On the other hand, Rendahl pointed out, spreading costs across the board can result in disproportionate burdens for some customers. In Washington, she noted, utilities are required under the CETA to demonstrate that any changes will create societal, economic, and public health benefits and that certain groups will not be overburdened. Katofsky added that DER hosts have historically paid certain integration costs, although some states are implementing “make-ready” programs to support EV charging deployment, in which the costs of both utility-side and customer-side investments (excluding the EV chargers themselves) that have calculated net benefits for all customers are spread across the rate base. These programs address a barrier to EV charger deployment while balancing costs and benefits between individual customers and the system as a whole, and they could work for other types of DERs.

Balancing Visibility with Privacy

A workshop participant raised the question of how to balance customers’ expectations of privacy with utilities’ desire for behind-the-meter visibility. Rendahl replied that in the case of DER aggregations, visibility is needed because they impact the entire system in a way that single DERs do not. An “opt-out” option may satisfy customers who prefer not to share their data, but the more customers are interacting with the grid, the more visibility utilities need to balance resource demand with energy adequacy. Glick suggested that customers who voluntarily connect with the grid should expect to share their data, as their DERs impact grid reliability. Subatki noted that the language used in communicating with customers about these issues raises some important nuances. While a DER owner might resist letting a utility “control” their DER or deploy “telemetry” to monitor it, they might allow utilities to “dispatch” their energy or have “visibility” into their DER, concepts that might not be fundamentally different but that are more palatable for customers. A member of the audience agreed that word choice is very important and suggested that stakeholders would be wise to approach these issues with appropriate sensitivity to customers’ privacy.

Katofsky pointed out that utilities do use customers’ data to manage their systems and in their work with contracted third parties, but data sharing is currently much less effective when it comes to direct-to-consumer third parties. He suggested that systems for data sharing could be streamlined and optimized to balance seamless data sharing, when warranted, with strong privacy and data protections for customers. Rendahl agreed, clarifying that when utilities use customer data to manage their services, they are obligated to protect it.

Attending to Distribution-Side Issues

Workshop attendee Don Hall, Quanta Technology, suggested that there could be more attention afforded to energy distribution utilities in these discussions. He noted that their challenges are very different from those of transmission companies and system operators, and suggested that states should allow distribution utilities to increase their hosting capacity. Rendahl agreed that capacity hosting is important for utilities and those seeking grid interconnections, but that state legislatures provide direction and authority for many state commissions, which impacts whether a state commission may require that capacity hosting data be made available. Hall pointed out that distribution companies may not have the resources to collect that data.

Besser suggested that utilities’ cost-benefit analyses include investments to leverage DERs. Hall stated that they already do, and regulators and engineers also collaborate on incorporating new technological advancements, but the process is very complex, especially in multistate agreements where utilities expect to pay for expansions with rate increases.