Opportunities and Challenges for the Development and Adoption of Multicancer Detection Tests: Proceedings of a Workshop (2025)

Chapter: Proceedings of a Workshop

Proceedings of a Workshop

WORKSHOP OVERVIEW1

Cancer screening is considered a key cancer control strategy because patients who are diagnosed at earlier stages of disease often have better treatment options and improved health outcomes. However, effective screening tests are lacking for most cancers. The development of minimally invasive approaches to screen for multiple tumor types at once could address this unmet need, but the clinical utility of multicancer detection (MCD) testing has yet to be established.

To examine the state of the science for the clinical use of MCD testing, the National Cancer Policy Forum of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine hosted a workshop on October 28 and 29, 2024, which brought together participants with backgrounds in clinical care, cancer research, health care policy, patient advocacy, and related areas.

This Proceedings of a Workshop summarizes the workshop presentations and discussions, and the observations and suggestions from individual participants are discussed throughout the proceedings. Observations on the

___________________

1 This workshop was organized by an independent planning committee whose role was limited to identification of topics and speakers. This Proceedings of a Workshop was prepared by the rapporteurs as a factual summary of the presentations and discussions that took place at the workshop. Statements, recommendations, and opinions expressed are those of individual presenters and participants and are not endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, and they should not be construed as reflecting any group consensus.

BOX 1

Observations from Individual Workshop Participants on the Opportunities and Challenges of Multicancer Detection Testing in Clinical Use

Current State of MCD Testing Development, Evaluation, and Clinical Use

- Multicancer detection (MCD) testing has the potential to increase cancer screening rates and expand cancer detection capabilities by testing for multiple cancers in a single blood test. (Beer, Castle, Eagle, Gordon, Klein)

- The use of MCD tests is likely to increase the number of patients recommended for follow-up diagnostic tests. In some cases, the tissue of origin may be unknown, or the diagnostic pathways may be undefined. (Doubeni, Hoffman, Kang, Keating, Krist)

- To date, the evidence on MCD tests focuses on diagnostic performance and not patient outcomes; their real-world clinical utility largely remains unknown (e.g., reduction of targeted cancer-specific mortality). (Castle, Hoffman, Myers, Patriotis, Rubinstein)

- The sensitivity, specificity, and clinical utility of MCD tests vary among cancer types and populations. (Etzioni, Grady, Katki, Klein, Lange, Patriotis, Rubinstein, Schrag)

opportunities and challenges of MCD testing in clinical use are presented in Box 1, and suggestions to advance knowledge and policy around MCD testing in clinical use are presented in Box 2. Appendixes A and B include the workshop Statement of Task and agenda, respectively. Speaker presentations and the workshop webcast have been archived online.2

EXAMINING OPPORTUNITIES AND CHALLENGES OF MULTICANCER DETECTION TESTS IN CANCER CARE

Beth Karlan from the University of California, Los Angeles noted that MCD tests might facilitate the development of a new paradigm in population screening because of their potential utility in detecting malignancies that have

___________________

2 https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/42236_10-2024_opportunities-and-challenges-for-the-development-and-adoption-of-multicancer-detection-tests-a-workshop (accessed December 26, 2024).

- MCD tests are not an adequate replacement for currently recommended cancer screening procedures, especially those, such as colorectal and cervical cancer screenings, that have the capacity to prevent future cancers. (Castle, Doubeni, Hoffman, Shulman)

- The commercial availability of MCD tests in the absence of regulatory review complicates the challenges of assessing them in randomized controlled trials. (Castle, Friedman, Katki, Shulman)

Considerations for Broader Implementation of MCD Tests

- The use of modeling and alternative endpoints based on cancer stage may be helpful in understanding clinical utility, but these approaches also have drawbacks and limitations and are not a substitute for data on clinical outcomes. (Beer, Castle, Eagle, Etzioni, Katki, Lange, Robbins, Schrag)

- Further research is needed to fully evaluate the economic and health system impact of MCD tests. (Beer, Doubeni, Eagle, Phillips, Ramsey, Shih)

NOTE: This list is the rapporteurs’ synopsis of observations made by one or more individual speakers as identified. These statements have not been endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. They are not intended to reflect a consensus among workshop participants.

no other available screening method. However, much remains unknown about the capacity of MCD testing to increase early cancer detection and to reduce cancer mortality. In addition, there are concerns about broad implementation and the possible ramifications for all the parties involved, including patients, clinicians, payers, and health systems.

Many participants discussed various MCD testing approaches in development and how MCD testing fits into the overall cancer screening landscape.

Cancer Screening for Early Detection

Robert Smith from the American Cancer Society (ACS) described how the emphasis on early detection as a form of cancer control stems from two century-old realizations: cancer begins as a localized disease and progresses to become systemic, and mortality rates often decrease when cancer can be detected early, before patients become symptomatic.

BOX 2

Suggestions from Individual Workshop Participants on Advancing Knowledge and Policy Around Multicancer Detection Test Development and Clinical Use

Enhancing Communication and Education

- Provide patients and the public with accurate information about the current evidence on potential benefits, limitations, harms, and unknowns of multicancer detection (MCD) tests. (Doubeni, Friedman, Green, Hoffman, Hoyos, Keating, Myers, Smith)

- Educate primary care clinicians about MCD tests, including their capabilities and limitations, regulatory status and guidelines, and costs/insurance coverage, to better equip them to support shared decision making with patients interested in using these tests. (Doubeni, Gordon, Hoffman, Myers)

Validating MCD Tests for Clinical Use

- Pursue further research on the performance and clinical utility of MCD tests through randomized controlled trials and other studies using strategies like incorporating real-world data. (Castle, Doubeni, Eagle, Etzioni, Hoffman, Katki)

- Establish standards for sensitivity measures. (Etzioni, Hagenkord, Phillips, Rubinstein)

- Establish a registry of individuals who undergo MCD testing to provide data on results and follow-up. (Hoffman, Martínez, Schrag)

- Enhance clinical trial participation. (Castle, Friedman, Green, Issaka, Schrag)

Implementing Effective MCD Testing

- Reduce challenges to follow-up diagnostics and care that may be recommended based on MCD test results. (Doubeni, Castle, Guerra, Hoyos, Issaka, Keating, Myers)

- Consider how the broader use of MCD testing might impact clinical workflows and demands, and anticipate potential future needs in terms of workforce, equipment, and infrastructure. (Hoffman, Karlan, Pisano, Shulman, Smith)

NOTE: This list is the rapporteurs’ synopsis of suggestions made by one or more individual speakers as identified. These statements have not been endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. They are not intended to reflect a consensus among workshop participants.

Smith presented examples of how cancer screening tests have evolved and expanded for early detection of cervical, breast, colorectal, lung, and prostate cancers (ACS, 2021). Despite this progress, cancer remains among the leading causes of death worldwide (Bray et al., 2024), and options for screening, diagnosing, and treating many cancer types remain limited. Philip Castle from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) pointed out that while screening tests exist for several of the most common cancer types, more than half of U.S. cancer deaths are from cancer types with no validated screening tests (Philipson et al., 2023). Cancer remains the second-leading cause of death in the United States (CDC, 2024a). Craig Eagle of Guardant Health stated that most patients do not get the recommended cancer screenings, and most patients are diagnosed only after they become symptomatic, so a different approach is needed.

Smith said that the challenges of conducting randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to assess the impact of a screening test on cancer mortality has slowed progress in developing and deploying effective cancer screening tests. Such RCTs are very expensive and complex to initiate and launch; have cumbersome enrollment and follow-up processes; can be vulnerable to low statistical power; and can lose relevance if new methods emerge while trials are underway (Smith et al., 2008). He said that finding ways to shorten the length of time between developing promising new screening approaches, confirming their efficacy, and broadly implementing them could accelerate progress.

To understand the realities of how cancer screening is implemented once tests are validated and in clinical use, it would also be important to consider how people perceive and use them. Jody Hoyos from Prevent Cancer Foundation described how she works to advance early detection by focusing on how people feel about screening, what options they have to use the tests, and how community partnerships can help. She explained that even when tests are in clinical use, there can be gaps in terms of who is eligible for screening, whether it is available or affordable, and who benefits from it (AACR, 2024). She expressed her belief that more people would be screened if the tests were less invasive, faster, and more convenient and underscored the importance of providing clear and objective information about cancer screening and improving availability and access.

Multicancer Detection Tests Approaches

Many participants provided an overview of MCD testing approaches that are in various stages of research, development, evaluation, and use. William Grady from the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center and Wendy Rubinstein from NCI described approaches used to collect, sequence, and analyze cell-free

DNA (cfDNA)3 cancer biomarkers circulating in blood plasma, which form the basis for most of the current generation of MCD tests. Grady and Rubinstein also discussed protein-based biomarker assays and emerging research on additional types of markers.

Grady explained that current approaches to MCD testing generate millions of data points that are assessed using artificial intelligence (AI) methods using sample sets from people with representative tumors to develop a specific biomarker signature. He noted that most MCD tests are based on AI-informed patterns of cancer using cfDNA markers alone, proteins alone, or a combination of the two. Researchers are also studying potential emerging markers that could be incorporated into MCD test assays, including exosomal mRNA, microRNA, and possibly DNA;4 circulating microbial DNA;5 and autoantibodies.6 He described three classes of DNA features that are often used in cfDNA-based biomarker assays, like MCD tests. First, Grady discussed detecting genomic sequence alterations. He explained how improvements in sequencing technology have enabled the detection of a variety of cancer-linked genomic mutations, such as single nucleotide variants, copy number alterations, fusion genes, and gene deletions. The second class is aberrant DNA methylation patterns that can be used to detect cancer cell DNA. While normal cell DNA has an established methylation pattern that is unique to each tissue type and reflects both gene expression and tissue of origin, tumor or precancerous DNA methylation patterns are identifiably different but still retain the tissue of origin information, making it possible to detect the cancer’s origin (Heredia-Mendez et al., 2023; Zhong et al., 2016). However, aging, dietary factors, and medication can also alter DNA methylation patterns, affecting the specificity of methylated DNA as a biomarker. A third DNA feature is the characterization of the cfDNA fragments patterns, called fragmentomics. When DNA is released into circulation, it is fragmented into small pieces that are less than 200 base pairs in length. Fragmentomics involves analyzing and characterizing the many features of the fragmented DNA (e.g., size distribution, blunt or jagged ends, circular or linear). Fragmentomics can detect

___________________

3 Cell-free DNA are fragments of DNA genetic material that are found outside of cells. See https://www.genome.gov/genetics-glossary/Cell-Free-DNA-Testing (accessed January 7, 2025).

4 Exosomal RNA and DNA are fragments of genetic material in membrane-encapsulated structures. See https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/exosome (accessed January 7, 2025).

5 Circulating microbial DNA are fragments of microbe genetic material found outside of cells (Pietrzak et al., 2023).

6 An autoantibody is “an antibody made against substances formed by a person’s own body.” See https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/autoantibody (accessed January 7, 2025).

differences between healthy cfDNA fragments and tumor DNA fragments, which tend to be shorter and more variable (Ding and Lo, 2022). Fragment patterns also can reveal which genes are turned on or off and the cancer cell’s site of origin. Grady said that using these three approaches in concert can help to improve test sensitivity, specificity, and pinpoint the cancer site of origin.

Protein-based biomarkers have also been included in some MCD tests. Grady said that this approach could increase sensitivity for detecting early cancers but noted that protein-based assays are currently tedious to develop and limited by the performance of the antibodies available to detect the proteins.

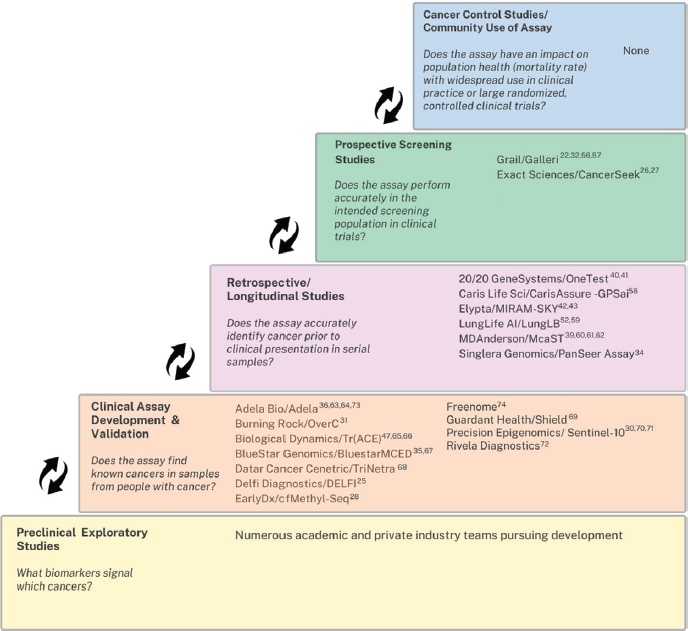

In terms of where MCD tests are in the pipeline from research to deployment, Christos Patriotis from NCI and Rubinstein reported that most biomarkers for MCD tests are at the early to middle stages of the five-phase framework of development defined by the Early Detection Research Network (see Figure 1) (Rubinstein et al., 2024). Patriotis noted that studies have shown that as tests move from early to later phases, their sensitivity tends to drop, adding that no MCD tests to date have demonstrated any readiness for routine use in population-based cancer control (Rubinstein et al., 2024).

Three participants described how their companies approach MCD test development and validation. To pursue the goal of detecting clinically relevant cancers with high accuracy and low false-positive rates, Eagle said that Guardant Health first considers assay performance measures, such as cancer type, test accuracy, positive predictive value (PPV),7 and outcome, all which factor into analytical and clinical validity. In clinical testing, the company uses alternative endpoints and real-world evidence to bypass the challenges of RCT execution, such as sample size and time commitment. In addition to evaluating technical performance, he noted that Guardant Health also works with partners to assess the potential health impact, access, and acceptance of MCD tests in development. For example, recognizing that colon cancer is still the second-leading cause of cancer deaths despite decades of screening and that 75 percent of these deaths occur in people who were not screened (Doubeni et al., 2019; Siegel et al., 2024), Eagle said that the company seeks to understand how MCD tests can help to bridge this gap by screening more patients more easily (Chung et al., 2024).

Tomasz Beer from Exact Sciences described how his company is working to create an MCD test that uses several biomarker classes to detect multiple cancers across all stages with high sensitivity and low false positives. This work is built on multiple feasibility and development studies (Allawi et al., 2022; Cohen et al., 2018; Douville et al., 2020, 2022; Katerov et al., 2021; Lennon et al., 2020), and recent studies have demonstrated a high specificity for many cancers, including those that lack established screening methods and those with

___________________

7 The chance that a positive test is a true positive (Monaghan et al., 2021).

NOTE: MCD = multicancer detection.

SOURCE: Patriotis presentation, October 28, 2024; Rubinstein et al., 2024. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

a high mortality rate (Douville et al., 2024; Gainullin et al., 2024). Beer said that his company recently launched a study that will involve 25,000 patients over 7 years,8 and concurrent research is underway to further advance validity and utility testing approaches.

Eric Klein from GRAIL, Inc. described GRAIL’s activities in evaluating its cfDNA-based MCD tests, which include clinical studies collectively involving nearly 400,000 patients.9 In one study, the MCD test detected 45 cancer

___________________

8 See https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06589310?lead=Exact%20Sciences%20Corporation&rank=1 (accessed January 23, 2025).

9 See https://assets.grail.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Galleri_Fact-Sheet_053023-Final.pdf (accessed January 15, 2025).

types for which no current screening test exists and preferentially detected aggressive cancers (Chen et al., 2021; Klein et al., 2021). He noted that sensitivity varies across cancer types, because only some shed cfDNA; for the 12 highest-shedding cancers, the test’s early-stage sensitivity was 67 percent. He also noted that the test showed a low rate of overdiagnosis10 of nonaggressive cancers. Klein said the test had high predictability for finding cancer signal origin and performed well at detecting higher-grade prostate cancers (Mahal et al., 2024). He said both studies showed a low false-positive rate, high location accuracy, robust PPV, and reduced time to diagnosis. Klein added that the preclinical detectability window could determine an appropriate testing interval, noting that preliminary evidence suggests yearly MCD test screening (Patel et al., 2023; Vachon et al., 2024).

In addition to the research undertaken by MCD test developers, several initiatives are underway to evaluate MCD technologies more broadly. Castle described how the NCI Cancer Screening Research Network11 is evaluating multiple screening technologies, including MCD tests, across broad populations. Its pilot study, Vanguard,12 is set to launch in 2025 and aims to address the feasibility of conducting RCTs to understand how MCD tests might be used to screen for multiple cancer types, with the goal of reducing cancer mortality. The Vanguard study aligns with several of the goals of the National Cancer Plan,13 which focuses on strategies to detect cancer early, deliver optimal care, eliminate inequities, and engage every person, Castle noted.

Rubinstein said that no MCD tests have been authorized for use by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (DCP, 2024). She described additional research to assess clinically available MCD tests, which FDA classifies as laboratory-developed tests (LDTs).14 She explained that federal regulations allow MCD tests to be used in clinical care as LDTs without undergoing FDA review, albeit with a few limitations. First, they must be designed, manufactured, and used within a single clinical laboratory; distribution for use in other

___________________

10 See https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/overdiagnosis (accessed January 17, 2025).

11 See https://prevention.cancer.gov/major-programs/cancer-screening-research-network-csrn (accessed January 10, 2025).

12 See https://prevention.cancer.gov/major-programs/cancer-screening-research-network-csrn/vanguard-study (accessed January 10, 2025).

13 See https://nationalcancerplan.cancer.gov/ (accessed January 10, 2025).

14 LDTs are “in vitro diagnostic products (IVDs) that are intended for clinical use and designed, manufactured, and used within a single clinical laboratory that is certified under the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 (CLIA) and meets the regulatory requirements under CLIA to perform high complexity testing.” See https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/laboratory-developed-tests-faqs/definitions-and-general-oversight-laboratory-developed-tests-faqs (accessed January 15, 2024).

laboratories is not allowed without FDA oversight. The clinical laboratory must also meet the quality standards of the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA)15 and demonstrate test analytical validity, although it is not required to demonstrate clinical validity or clinical utility, such as reduced mortality. Despite some overlap between FDA and CLIA standards, Rubinstein noted that, unlike FDA, CLIA does not require public reporting of adverse effects or preapproval of test labeling (Rubinstein et al., 2024). She said that there is currently no comprehensive list of LDTs available to the public, and no such list is mandated.

Potential Benefits of Multicancer Detection Tests

Several participants described how MCD tests could potentially present new opportunities to increase screening rates, detect cancers earlier, and detect a broader range of cancer types. Because current screenings only detect 14 percent of cancers (Siegel et al., 2024), Beer stated that MCD testing could transform early cancer detection. Despite the many unknowns, Castle said that MCD tests show promise for detecting cancers that have no other screening tests. He added that these tests could also help to shed light on the natural history of various cancers, potentially leading to new treatment options. In addition, by identifying multiple cancers with a single blood test, Castle said that MCD tests could be an appealing option for patients compared with multiple screens or more invasive screening methods (Cotner and O’Donnell, 2024; DCP, 2024).

While much of the discussion of MCD testing has focused on their utility in detecting cancer before symptoms develop, several participants noted that they could be used for other purposes as well, including diagnosing symptomatic disease, targeted screening for high-risk groups, or monitoring cancer during and after treatment. Robert Winn from Virginia Commonwealth University Massey Cancer Center suggested that MCD tests may also provide clinically useful insights into “cancers of unknown primary,”16 which are very difficult to treat.

Challenges and Potential Pitfalls of Multicancer Detection Tests

While there are multiple approaches to designing and evaluating MCD tests, most of the studies to date have focused on diagnostic performance, not outcomes, and their clinical utility at the population level remains unproven.

___________________

15 See https://www.cms.gov/medicare/quality/clinical-laboratory-improvement-amendments (accessed January 15, 2025).

16 Primary cancer is a term used to describe the original, or first, tumor that has spread to other parts of the body. See https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/primary-cancer (accessed January 10, 2025).

Many participants emphasized this and other areas in which the evidence is lacking for MCD testing and pointed out some potential consequences that should be considered.

Castle said that while technical capabilities of MCD tests are promising, more research is also urgently needed to determine whether these tests reduce cancer mortality. He also suggested a need to further build the evidence base around which tests have the most clinical utility, what implementation and access challenges they may raise in real-world use, which populations benefit most from which test, the optimal intervals for using MCD tests, and their potential utility in improving tumor staging, risk assessment, care delivery, or the patient experience. He also discussed certain challenges with screening tests, some that are common among all screening tests and some specific to MCD tests. For example, there is always a risk of false-positive or false-negative results, which can have many implications for a patient’s subsequent actions and physical and mental health. In addition, receiving a positive or inconclusive test result can set patients on a path toward invasive procedures and associated costs and complications, which may be unnecessary.

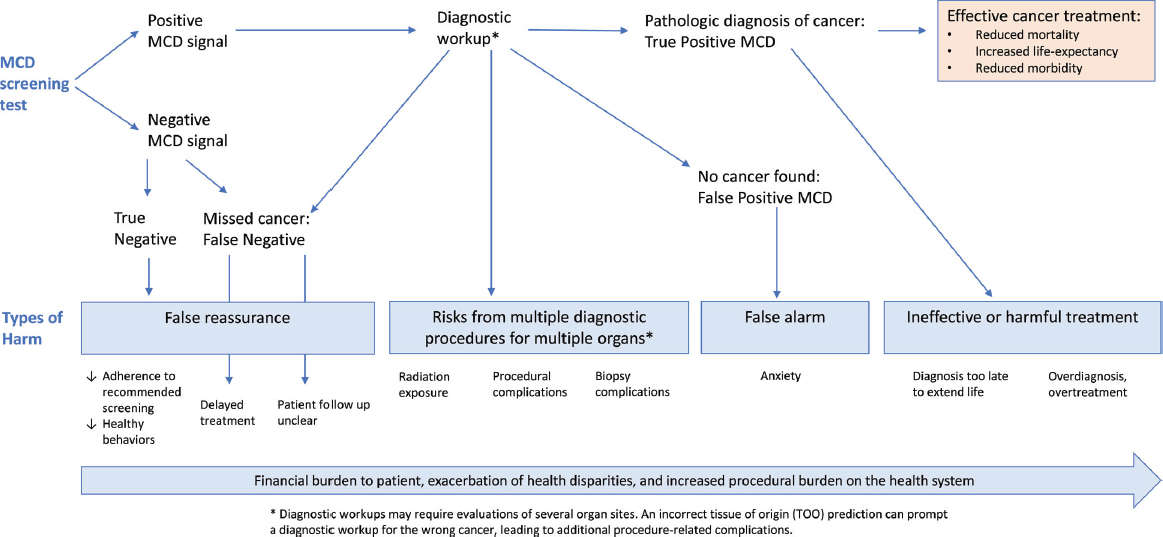

Rubinstein shared a diagram of the possible outcomes from an MCD test that illustrates types of “potential harms” that patients can experience at various steps that may be triggered by both positive and negative results (see Figure 2). Rubinstein noted that while people see MCD tests as simpler and less invasive than conventional screening methods, they also can elicit fear, anxiety, and mistrust (Roybal et al., 2024; Samimi et al., 2024). Several other participants emphasized the importance of considering how MCD testing fits into the overall cancer care experience.

Sue Friedman of Facing Our Risk of Cancer Empowered discussed specific challenges for groups with a high risk for cancer. Her organization advocates for patients with increased hereditary cancer risk, such as those with BRCA17 mutations or Lynch syndrome.18 Friedman explained that these individuals face different burdens than the general population, including a higher overall lifetime risk for cancer, an increased risk for multiple cancers, and a higher risk of cancer at young age. She described how intensive screening recommendations for high-risk individuals can create heavy burdens, includ-

___________________

17 BRCA (BReast CAncer genes) codes for proteins that repair DNA damage, and inherited mutations to these genes greatly increase a person’s chance of developing breast cancer. See https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/genetics/brca-fact-sheet (accessed January 10, 2025).

18 Lynch syndrome increases the chance that a person develops multiple types of cancers. It is caused by inherited mutations to several genes that repair DNA errors that occur during duplication. See https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/lynch-syndrome (accessed January 10, 2025).

NOTE: MCD = multicancer detection.

SOURCE: Rubinstein presentation, October 28, 2024; Rubinstein et al., 2024. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

ing high out-of-pocket expenses, long travel times, and high anxiety with every screening. Tests capable of identifying multiple cancers could help to ease these burdens, but to be successful in this context, Friedman stressed that the tests must be rigorously validated for different populations and in high-risk settings. “It is important for the research community and MCD test developers to be transparent about MCD test benefits, risks, limitations, and clinical utility and avoid perpetuating hype that can raise false hopes,” Friedman added. Castle agreed and stressed that all interested parties, from patients to researchers to clinicians, have a role in ensuring a future where MCD testing is safe and evidence based, contributes to cancer reduction goals, and leads to improved health outcomes and lives saved.

MULTICANCER DETECTION TESTS: FROM PERFORMANCE TO OUTCOMES

Many participants discussed approaches and evidence for analytical performance, clinical validation, and clinical utility of MCD tests and research gaps and opportunities to further strengthen the evidence base.

Understanding Multicancer Detection Test Performance

Ruth Etzioni from the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center offered an overview of some key concepts that can help researchers and clinicians interpret study results. The results of cancer screening tests are interpreted based on a predicted probability that a patient has cancer; this requires defining a threshold above which a test is declared positive and below which it is considered negative. While a high threshold will limit false positives (leading to high specificity), it will reduce true positives as well (leading to low sensitivity). To reduce unnecessary biopsies and follow-up tests, most first-line tests are set with a high threshold, leading to high specificity and PPV but lower sensitivity.

Etzioni said that MCD tests have been shown to have a wide range of sensitivity rates for different cancers and among symptomatic and asymptomatic people (Liu et al., 2020; Schrag et al., 2022, 2023). Sensitivity can also be influenced by biases in empirical sensitivity rates or flaws in the diagnostic process (Lange et al., 2023). Because the researchers set the threshold for determining a positive versus negative result, Etzioni noted that a high PPV does not necessarily indicate a test’s accuracy (Raoof and Kurzrock, 2024). Research has not yet demonstrated that first-line screening MCD tests have high sensitivity for early-stage cancers (Pinsky et al., 2023). Castle added that it is important to examine the negative predictive value alongside the PPV to be able to confidently assure a patient that they do not have cancer and inform the appropriate intervals for screening.

Clinical Trial Design and End Point Selection

Hormuzd Katki from NCI discussed several challenges with conducting RCTs and other types of studies that can limit their generalizability for assessing MCD validity and utility. In many types of study designs, but especially for observational studies, it is challenging to control for confounding variables related to the characteristics of people who choose to get screened outside of screening guidelines, who tend to be “health seekers” with below-average mortality rates (García-Albéniz et al., 2020). It is difficult to predict the characteristics of those who will or will not choose MCD testing or determine how to quantify and account for their health-seeking behavior. To enhance internal validity, he said, RCTs tend to sacrifice external validity19 by recruiting people who are healthier than the target population (due to their self-selected nature and trial eligibility criteria) and treating them in major medical centers, which are associated with above-average outcomes (Katki et al., 2016). As a result, RCT-based estimates of mortality benefits may not translate to the general population that may be considered for screening.

Katki shared two approaches to help address these concerns and increase the statistical power of RCTs. First, researchers can use Hu-Zelen modeling20 to calculate how many yearly MCD tests would reduce mortality rates (Hu et al., 2024). This approach achieved 90 percent power for analyzing the use of MCD testing for nine cancer types in a relatively short time span of about 7–9 years. Second, Katki described how testing stored blood specimens in the control arm (and not just the screened arm) of a trial can be used to reduce the necessary sample size or accelerate the time while still achieving 90 percent power. This approach, which Katki called “intended effect design and analysis,” reduces the “noise” of participants who have never had a positive test result by exploiting information gained by testing stored specimens in the control arm. Katki said that it can increase the statistical power for any outcome, particularly non-screened cancers; allows accurate predictions of mortality reduction with a smaller sample or shorter time frame; and is in accordance with the principles of medical ethics (Katki et al., 2024). Variants to this

___________________

19 Internal validation refers to the “degree to which a study establishes the cause-and-effect relationship between the treatment and the observed outcome,” and external validation is the extent to which the research results can be generalized to the general population (Slack and Draugalis, 2001).

20 Ping Hu and Marvin Zelen developed a model to plan early detection RCTs, adjusting variables like the number of exams, sample size, intervals between examinations, and followup time to have greater statistical power (Hu and Zelen, 2004). Statistical power is calculated before the study initiation informs the study parameters. It determines the “probability that one will correctly reject the null hypothesis,” with a higher power meaning that results could be more conclusive (Dorey, 2011).

approach can also be used to design better studies of MCD tests (Hackshaw and Berg, 2021; Weiss, 2024).

Several participants discussed the challenges with defining meaningful endpoints for assessing MCD tests. Mortality is the benchmark in cancer screening research, but assessing mortality benefits requires long-term studies, which is a problem because MCD tests are being commercialized far more rapidly than mortality studies can be completed. Eagle said that companies need to generate data on their MCD tests quickly, efficiently, and consistently so that they can commercialize without waiting years to demonstrate clinical validity. New tests or therapies can also render the technology under examination obsolete while studies are ongoing. To fill the evidence gap, Beer suggested that alternative endpoints, such as reduced late-stage cancer diagnoses, reduced disease burden, and improved quality of life, could be studied to measure direct patient benefit other than mortality as well as to predict for mortality and shorten this time frame (Dai et al., 2024; Hackshaw and Berg, 2021; Klein et al., 2023).

Another potential alternative endpoint is the effect of screening on the incidence rate of late-stage cancer, which Rubinstein and others noted has not yet been proven to be a sufficient surrogate for mortality (Rubinstein et al., 2024). Hilary Robbins from the International Agency for Research on Cancer discussed how focusing on the relative reduction in late-stage cancer could enable faster, smaller, and less expensive trials but also highlighted some challenges with this approach (Neal et al., 2022). Robbins noted that the term “stage shift” can have different meanings, and that quantifying “a shift in the proportion of cancers that are diagnosed at late stage,” is a less robust outcome that is not indicative of mortality reductions, because the number of early-stage diagnoses may increase without affecting late-stage diagnoses.

In a systematic review of cancer screening trials, she and her team focused on the leading alternative endpoint, late-stage cancer incidence, which is not influenced by the diagnosis of early-stage cancers. They found that the relationship between late-stage cancer incidence and mortality depends on the cancer type (Feng et al., 2024), with a close correlation for ovarian and lung cancer but little or no correlation for other cancers, including breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer (Feng et al., 2024). Klein pointed to a study that demonstrated a linear correlation between reduced late-stage cancer and cancer mortality (Dai et al., 2024), and Robbins said that the difference in conclusions between the two studies could be related to multiple factors including using different prespecified lengths of follow-up time before calculating endpoints.

Overall, Robbins offered four reasons to be cautious when considering late-stage cancer incidence as an alternative endpoint for assessing MCD tests. First, she said that cancers that are detectable with existing cfDNA-based MCD tests often have lower survival rates than those that are not. This threatens the

validity of using late-stage cancer as an alternative endpoint because, while the rate of late-stage cancer may go down when the cancer is caught earlier, the mortality rate may not (Callister et al., 2023). Second, it is important to recognize that some screening tests, such as colonoscopies, can prevent cancers from occurring altogether (CDC, 2024b), which is not the case for MCD tests, and this can change the relationship between stage and mortality-based endpoints. Third, new cancer treatments can change stage-specific survival rates, which means that the interpretation of cancer screening trials may need to shift over time to account for evolving treatment methods. Finally, MCD tests can lead to false reassurances that someone with a negative result truly does not have any cancers (DCP, 2024), which cannot be adequately studied in study designs where the participants are blinded as to their screening status. In light of these factors, Robbins noted that late-stage cancer reduction could be a suitable alternative endpoint in RCTs for MCD tests, but only for certain cancers. While they may reduce the incidence of late-stage cancers, the effect on mortality remains unknown because trial results combine a wide array of different cancer types into a composite late-stage endpoint.

Alex Krist from Virginia Commonwealth University agreed that it is important to reduce late-stage disease rates but noted the potential for overdiagnosis. Diagnosing patients earlier without improving outcomes is harmful because it extends the time a person lives with disease without lengthening their life. Castle added that what looks like a stage shift (reduction in the proportion of cancers diagnosed at late stage) could in fact be the inflation of early-stage diagnoses that are not clinically relevant (Doubeni et al., 2022a). Etzioni suggested that trials could collect information on overdiagnosis, an incidence endpoint that is different from the mortality endpoint. Castle agreed that trials should measure overdiagnosis and other harms, not just benefits, especially when they are enrolling a healthy population.

Challenges in Conducting Clinical Trials When Multicancer Detection Tests Are Commercially Available

Participants also discussed how the commercial availability of MCD tests—despite the fact that none have been reviewed by FDA—might impact clinical trial participation. Castle noted that some people may be unaware or unconcerned that these tests do not have proven benefits, especially if they initially entail a simple and relatively noninvasive blood draw. “I think we’re really at a critical juncture because these are being offered to the public without proven benefit,” he stated. If patients can obtain MCD tests without enrolling in a clinical trial, Friedman wondered whether people might be less motivated to participate in clinical trials. Castle replied that this is a possibility and would undermine the ability to build the necessary evidence base for clinical decision

making. Trial validity depends on randomization, but some people may not want to participate if they know they could be randomly assigned to not receive the MCD test, which they could otherwise access on their own. Lawrence Shulman from the University of Pennsylvania wondered whether covering the cost of MCD testing within clinical trials could incentivize participation, which would also have the benefit of increased communication and enhanced understanding and consent compared with testing outside of a clinical trial.

Friedman noted that many people in the high-risk community are highly motivated to participate in clinical trials and recognize that they have benefited from medical research. However, she emphasized that it is still important to make trials as convenient and easy as possible to encourage enrollment (NASEM, 2021, 2022).

Modeling Approaches and Applications

Many participants noted that RCTs are expensive and take years to conduct, and there can also be large gaps between MCD test performance in clinical trials and outcomes in the general population. Several participants highlighted opportunities for modeling to help address these challenges. Modeling enables researchers to extract maximum information from limited data, set expectations for trials, explore the relationship between projections and assumptions, and continually incorporate new data to improve output.

To accelerate progress in studying the potential benefits of MCD testing, Jane Lange from Oregon Health and Science University and her team developed a framework for modeling natural history and stage shift as they relate to mortality outcomes (Lange et al., 2024). Natural history models can be used to simulate the journey of individuals with no cancer through preclinical and clinical stages. She described how simulations were calibrated for 12 types of cancer to reflect when each cancer would be detected by an MCD test, when it would be diagnosed clinically in the absence of such a test, and what the reduction in late-stage disease would be. These simulations revealed two drivers of late-stage cancer reduction: early-stage sensitivity and detectable early-stage preclinical duration.

Lange said RCTs suggest MCD tests have high specificity, especially for late stages, and a good PPV for the general population, but sensitivity varies by cancer type (Owens et al., 2022). Stage-shift models have demonstrated that projected mortality is different for each cancer site and depends on the relative survival rates for each disease stage. These results are in agreement with observational data and indicate that MCD tests are likely to be associated with the greatest mortality reduction in common cancer sites with the highest mortality in unscreened patients. As a result of this, Lange said, “I think despite the fact that everyone is selling these MCD tests as being really good for detecting rare

cancers, it’s really going to be the common deadly cancers that are going to be driving the performance in the clinical trials at the end of the day.”

Etzioni said that a larger study designed to measure the reduction in late-stage incidence by subtype could further refine modeling around this relationship. Lange also emphasized that integrating more data from MCD tests on late-stage disease reduction and mortality would further improve models.

Beer asked Lange whether her group had modeled how therapy improvements may interact with future MCD tests. Lange answered that modeling treatment improvements for both early- and late-stage disease shows that when late-stage disease treatment improves, the benefit of screening goes down. When early-stage disease treatment improves, the benefit goes up.

Castle stated that modeling can be useful but cautioned that researchers need to be wary of over-interpreting the results and aware of potential biases or assumptions that undermine their ability to represent the general population.

CONSIDERATIONS FOR IMPLEMENTING MULTICANCER DETECTION TESTS IN THE CANCER CARE CONTINUUM

Many participants discussed the impact of MCD tests on the landscape of cancer screening, detection, diagnosis, and treatment from a broad array of patient, clinical, and health system perspectives. Recognizing that screening is not an isolated process but an integral part of the broader continuum of care, they also discussed the importance of ensuring appropriate follow-up and strategies for enabling effective communication before, during, and after MCD testing.

Perspectives on Multicancer Detection Tests in Different Clinical Contexts

Richard Hoffman from the University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine shared a primary care perspective, saying that it is essential for primary care clinicians to educate themselves and their patients about MCD tests because, while they may not yet be clinically validated, they are available, and patients are interested in using them (Guerra et al., 2024; Myers et al., 2023). Most primary care clinicians’ experience with cancer screening is limited to single-cancer screenings in asymptomatic patients, in accordance with evidence-based guidelines from the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF),21 which have clear pathways for following up on

___________________

21 See https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation-topics/uspstf-a-and-b-recommendations (accessed January 15, 2025).

positive results. However, most cancers lack validated screening tests (Islami et al., 2022; Shete et al., 2021).

Hoffman said that MCD tests, with their simplicity, convenience, and ability to screen for more cancers at once, could represent a paradigm shift and decrease the aggregate burden of cancer mortality. However, the benefits remain uncertain because they have not been validated by RCTs with mortality endpoints. Also, they cannot detect precancers, have lower sensitivity for early-stage cancers, and are not always applicable to individual patient needs (Feng et al., 2024; Klein et al., 2021; Neal et al., 2022; Rubinstein et al., 2024). Other challenges include a lack of diagnostic pathways, especially for very rare cancers; incomplete or insufficiently sensitive tests; and false positives, all of which can also contribute to patient anxiety. In light of these issues, Hoffman said that it is important for clinicians to consider MCD testing in the broader context of a patient’s life expectancy and ability to afford and willingness to undergo potentially invasive diagnostic tests, along with continuing to offer USPSTF-recommended screenings and preventive care (Kotwal and Walter, 2020).

Hoffman stressed the need for education and guidance to help primary care clinicians understand the potential benefits, limitations, and harms of MCD tests and ensure clinicians are aware that no MCD test has received FDA approval and none are currently covered by insurance (Rubin, 2024). He noted that when speaking with patients, clinicians need to be prepared to clarify the benefits and harms of MCD testing, address the costs and potential downstream outcomes, and emphasize that MCD testing does not replace the need for recommended screenings and healthy behaviors. He also emphasized the importance of shared decision making and balancing evidence-based medicine with patient values and preferences, which he said could be enabled by decision support tools (Chenel et al., 2018; Joseph-Williams et al., 2021; Muscat et al., 2021; Stacey et al., 2024). To support clinical workflows, Hoffman said that it will be important for health care systems to consider how MCD testing may affect the use of information technology to implement the new screening tests along with standard of care screening, the allocation of resources needed to engage patient navigation through follow-up of abnormal test results, and the integration of specialists involved in diagnostic evaluation and treatment.

Stella Kang from New York University Langone Health22 shared a radiology perspective, saying that much more research is needed to elucidate the benefits and downstream impacts of MCD testing. She noted that MCD test results could set patients onto different diagnostic pathways that could include

___________________

22 As of December 2024, Kang joined Columbia University Irving Medical Center and is no longer affiliated with New York University Langone Health.

multiple imaging sessions or more invasive testing, like biopsies, which could have limited system capacity and be costly for patients (Lennon et al., 2024; Nicholson et al., 2023). Follow-up imaging and testing results can also be inconclusive or lead to incidental findings unrelated to the MCD test results (Kim et al., 2023; Nguyen et al., 2017). The prevalence of incidental findings, for example, depends on the imaging modality and can be quite high, especially for older patients, which may affect patients’ willingness to undergo these procedures and could also lead to over- or under-treatment. Kang also noted that interpreting imaging results is not black and white but relies on establishing sensitivity and specificity thresholds. She added that for cancers with an established cancer screening method, MCD tests will have a high bar to pass before they could replace those methods. However, she suggested that combining MCD test results with imaging could potentially lead to MCD test-augmented strategies that replace or are integrated into the standard of care and may better balance clinical benefits and harms (Cohen et al., 2018; Kang et al., 2025; Lennon et al., 2020; Mahesh et al., 2023).

Deborah Schrag from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center said that from an oncology care perspective, MCD tests present both opportunities and challenges as they move from research to practice. One major opportunity she highlighted is the potential to establish partnerships between industry and the oncology community to create large-scale patient cohorts that, through minimally invasive procedures, can provide samples that multiple companies could leverage. Such a partnership could also refine sensitivity terminology, enhance the existing data cache, and improve modeling and simulations, Schrag said.

Highlighting how a focus on people who have a hereditary risk of cancer could help to advance MCD test evaluation, Ora Gordon from Saint John’s Cancer Institute and Providence Health described how her organization has partnered with GRAIL on studies of MCD testing implementation. For example, Galleri in Action (GIA) was an observational study and included high-risk groups such as those with a hereditary cancer risk, those with a family history of cancer, and cancer survivors, which then offered annual MCD testing to gene mutation carriers. Another study, Providence Evaluation of Annual Cancer Screenings (PREVAIL),23 is an ongoing RCT stratified by risk level of germline mutation carriers and offers participants annual MCD tests for 3 years to follow cancer outcomes and adherence to standard high-risk guidelines for screening and prevention, patient anxiety, and impact on barriers to care. To inform uniform diagnostic recommendations in these studies, as well as increase fluency about MCD tests and challenges, Gordon described how Providence Health established early-detection case conferences, in which a

___________________

23 See https://mced.providence.org/en/prevail/home (accessed March 4, 2025).

molecular tumor board24 meets to evaluate positive cases and collaborate on standardizing diagnostic decisions.25

Ronald Myers from Thomas Jefferson University highlighted how research has helped to elucidate patient perspectives on MCD tests. He shared data from one study showing that when given limited information, patients viewed MCD tests favorably and were open to using them (Myers et al., 2023). However, he said that more research is needed to determine whether patients would feel the same when given more extensive information that is more balanced, presenting both the potential benefits and harms of MCD testing. Myers suggested that to advance implementation, guidelines around MCD testing could mandate shared decision-making processes, support patient navigation programs, ensure coverage for all testing and follow-up diagnostics, and advance research into the efficacy of those processes. He added that shared decision-making resources could include patient education tools modeled after the International Patient Decision Aid Standards.26 Myers also called for the development and use of simple decision counseling tools that clinicians can use to help elicit patient values and preferences related to MCD testing and decide on a course of action that makes sense to the patient. Further, he highlighted the need to ensure that MCD testing is offered along with standard of care screening and the importance of ensuring repeat MCD and standard of care screening.

Addressing Multicancer Detection Tests in Care Pathways and Guidelines

Nancy Keating from Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Chyke Doubeni from The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center expressed concern about MCD tests already being offered to the public without review by FDA and despite a lack of clear follow-up pathways for positive results.

Keating defined a “good” test as one that will find treatable, curable cancers before symptoms occur, have minimal risks and high accuracy rates, and decrease cancer mortality rates. She noted that the emergence of less-invasive screening options and lack of agreement about the level of evidence required for their use could upend established screening recommendations.

___________________

24 A molecular tumor board is “a multidisciplinary team whereby molecular pathologists, biologists, bioinformaticians, geneticists, medical oncologists, and pharmacists cooperate to generate, interpret, and match molecular data with personalized treatments” (Vingiani et al., 2023).

25 See https://academyhealth.confex.com/academyhealth/2024di/meetingapp.cgi/Paper/69578 (accessed March 6, 2025).

26 See https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/IPDAS/index.html (accessed January 10, 2025).

Despite their promise, Keating said that issues such as invasive follow-up testing, overdiagnosis, overtreatment, false positives, patient anxiety, lack of access to care, and increased costs could mean that MCD tests bring more harm than benefit in low-risk populations. These harms can also apply to higher-risk patients, and of those, older patients may benefit more but also have a higher rate of overdiagnosis.

Pointing to unresolved questions about whether and when MCD tests will be reviewed by FDA, what type of evidence will be required, how they can be used most effectively, and how to educate clinicians and the public about their benefits and harms, Keating said that forthcoming evidence from RCTs and other studies may answer some of these questions but is also likely to raise new ones. She said that it is important for all interested parties—including patients, caregivers, clinicians, health organizations, policy makers, and others—to ask whether and for whom MCD test benefits outweigh their harms; how test data can be best leveraged to generate evidence and enhance shared decision making; how to handle conflicting or changing guidelines; and how to ensure broad implementation of effective tests and access to follow-up care.

Recognizing that internet search results can promote misinformation and marketing over scientific evidence (Crossnohere et al., 2024), Doubeni said that it is important to determine the best role for MCD tests in primary care and for patients and clinicians to examine multiple sources of information and have their concerns addressed before determining whether to use them (Doubeni et al., 2022b). He added that primary care and family clinicians, who are likely to be the ones answering patient questions and helping interpret their results, need more information about these tests, how they are evaluated, and what their results mean (Samimi et al., 2024). He cautioned that it is vital to consider the safety and effectiveness of MCD tests; their ability to detect early-stage or precursor lesions; the regulatory and insurance coverage context; and access to follow-up care pathways, recognizing that positive test results require follow-up procedures that may add to costs and strain health care resources (Han et al., 2022; LeeVan and Pinsky, 2024; Schrag et al., 2023). In light of these issues, Doubeni suggested focusing on improving cancer prevention and screening technologies for all cancers, retaining USPSTF evidence-based recommendations as the standard of care, placing strong emphasis on scientific evidence, and educating all interested parties on the benefits of evidence-based cancer screening.

Krist discussed MCD testing in the context of clinical guideline development. Recognizing that even preventive measures recommended in existing guidelines can cause harms, Krist explained that the USPSTF judges the certainty that the evidence accurately predicts benefits and harms, assesses the magnitude of both, and assigns a letter grade (A–D, or I for insufficient

evidence) for the net benefit of a preventive service to inform whether it should be recommended.27 Achieving moderate certainty requires studies with low risks of biases (such as RCTs), a demonstrated improved health outcome (which, Krist noted, can be difficult to define for quality-of-life improvements), and improved intermediate outcomes (which, for cancer, could include stage shift, detection of precancers, or biomarker changes). Collaborative modeling is also an important method to better understand the lifetime effects of different screening programs, better assess screening in specific populations, and combine services for enhanced benefits (Petitti et al., 2018). The USPSTF also publishes a yearly report on high-priority evidence gaps.28

Strategies for Ensuring Appropriate Communication and Follow-Up

Throughout the workshop, many participants emphasized that appropriate communication about what a test can and cannot show, as well as what happens after the results are returned are critical in determining the utility and impact of the test in the cancer care continuum.

To address this issue, Carmen Guerra from the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine suggested that it may be helpful, before MCD tests are widely implemented, for a collaborative patient engagement group to push for national legislation around follow-up coverage for screenings that have been proven to cost-effectively reduce mortality, to set a precedent for when MCD tests pass that bar. Some states already have laws that can serve as models; for example, she noted that New Jersey has cancer education and early-detection laws that mandate downstream diagnostic coverage.29,30

Elena Martinez from the University of California, San Diego, agreed that inadequate follow-up is a common and complicated problem in standard of care screening and is also likely to be an issue in implementing MCD testing. In addition to coverage, she emphasized that better patient communication is needed, and researchers are just now beginning to study this issue and examine alternate strategies. Karlan agreed that clear communication is especially important when discussing follow-up appointments and procedures,

___________________

27 See https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/about-uspstf/methods-and-processes/grade-definitions#july2012 (accessed January 17, 2025).

28 See, for example, https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/sites/default/files/2024-11/uspstf-annual-report-congress-2024.pdf (accessed January 16, 2025).

29 See https://www.nj.gov/health/ces/public/resources/njceed.shtml (accessed January 17, 2025).

30 See https://www.fightcancer.org/releases/legislature-supports-reducing-burden-cancer-new-jerseyans (accessed March 6, 2025).

and Shulman suggested that innovative approaches to patient communication could be part of new RCT designs. Etzioni added that modeling could potentially help to understand outcomes in patients with different treatment patterns and care access than what is represented in RCTs.

Several participants, including Cheryl Ivey Green from First Baptist Church of South Richmond, noted the lack of clear communication with the public about the risks and benefits of cancer screening in general. Green emphasized that it is important to think carefully about how to effectively deliver information in person through conversations with health care clinicians in the clinic, recognizing that many people are unaware of MCD tests and will need advice from trusted sources to understand and use them. She suggested that it may be easier for patients to speak freely about their fears with counselors or advocates, who have more time than clinicians and are less likely to recommend invasive testing. Even if patients are not eligible for MCD testing, Green added, such conversations can still shed light on their cancer risk and care options.

Karlan noted that some clinicians may struggle to strike the appropriate balance of discussing cancer screening and prevention while avoiding raising false hopes. Hoyos suggested that clinicians would be wise to use this time—before MCD tests become widely implemented—to have difficult conversations with patients about important topics like risks, screenings, and potentially invasive tests. Smith agreed, calling for clinicians to talk more openly with their patients about what is and is not known about cancer risk and what tests or screenings are available and recommended. Noting that the medical community should feel accountable for improving the public’s understanding of this topic, he said that this can also extend beyond the clinic, such as through efforts like a targeted multimedia public educational campaign.

Chanita Hughes-Halbert from the University of Southern California asked how clinicians might approach not only advising patients on whether to undergo MCD testing but also helping them process both the results and the emotions they elicit. Friedman said that people often feel a significant amount of fear around cancer tests (Vrinten et al., 2015), and it is important that conversations with health care clinicians include empathetic, emotional support from trained professionals. Green agreed, stating that it is important for everyone who works in this space to acknowledge the mental burden involved. She noted that several people that she works with are referred to therapists or advocates to help process their fears and anxiety around cancer tests.

Positive and negative MCD test results might have different psychological implications for patients. Scott Ramsey from the Hutchinson Institute for Cancer Outcomes Research at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center noted that, although the chance of a positive result is low for each individual test, that chance increases if tests are taken multiple times over the course of a lifetime.

HEALTH SYSTEM, ECONOMIC, AND POLICY CONSIDERATIONS

Several participants reflected on the policy and economic factors that influence how tests are incorporated into clinical workflows and used by health systems.

Health Equity Considerations to Overcome Challenges Facing Different Populations

Rachel Issaka from the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center described how systemic challenges facing different populations have resulted in disparities in social drivers of health, including housing, transportation, and socioeconomic factors such education and income, and disparities in health outcomes for “minoritized populations and medically underserved populations” (AACR, 2024). Issaka said that “ultimately this leads to disparities across the cancer care continuum, starting really at the point of developing disease all the way through survivorship.” Guerra stressed the importance of taking steps to ensure that new tools and interventions, such as MCD testing, are widely disseminated and implemented to benefit everyone. She said that this is unlikely to happen on its own but requires intentional interventions that acknowledge the many challenges that exist at the policy, institutional, clinician, and patient levels (Miller et al., 2024; Roybal et al., 2024).

Many participants discussed how differences in MCD test information, availability, and access might play out across patient, clinician, and institutional levels. At the patient level, Guerra said that challenges to MCD testing knowledge and use could include a variety of factors, such as costs, limitations in availability of the test or follow-up care, lack of trust or language and literacy accommodations, and insufficient patient navigation capacity (Saurman, 2016). She said that more than 100 million people in the United States do not receive regular care (NACHC, 2023). “It is important for us to design a system where we intentionally try to reach these disenfranchised patients,” Guerra added. She emphasized that it is important to make MCD tests available to federally qualified health centers and tribal nations; develop mobile education and screening strategies that incorporate different languages and cultures; and partner with trusted messengers, such as faith leaders and unions.

At the clinician level, Issaka said that it is important for clinicians to be consistent and systematic when discussing the need for cancer screenings with all patients, to ensure that all can participate (Carroll et al., 2024; May et al., 2015). For example, the World Health Organization framework for effective health communication emphasizes that patients should receive acces-

sible, actionable, credible, relevant, timely, and understandable information.31 Following this framework also helps clinicians build trusting relationships with patients, improves understanding and uptake, and creates opportunities for more effective health care collaborations, Issaka added. Guerra emphasized the importance of empowering clinicians to guide patients through a positive test result and follow-up steps.

At the institutional level, Guerra emphasized the importance of recognizing and addressing the distribution of cancer centers across geographies. Different populations, such as rural populations, often have fewer diagnostic and screening sites, and the facilities in these areas often offer fewer services and have older equipment (Himmelstein and Ganz, 2024; White-Means and Muruako, 2023). Guerra said that establishing partnerships with better-resourced health centers and relevant organizations will be critical to improving care for all.

Issaka emphasized that it is critical to ensure that results from MCD clinical trials are generalizable to the U.S. population (Klein et al., 2021; Samimi et al., 2024). This could be achieved by setting a priori recruitment goals and metrics that “prioritize equity and expand the availability of clinical trials” to all patients (Unger et al., 2021). Doubeni added that it may also be possible to generate real-world evidence for the effectiveness of MCD testing across populations by building in clinical studies during the implementation and marketing phases as these tests are deployed.

Winn noted that cancer outcomes are worst in areas of persistent poverty, regardless of race (Moss et al., 2020). He asked how those populations could not only receive MCD tests but also be assured of coverage for them and any needed follow-ups. Issaka agreed that cancer centers in rural areas are often overwhelmed and under resourced and may offer screenings but not have the capacity for follow-up care. She suggested that new centers, in carefully chosen locations, are needed to increase access. Etta Pisano from the American College of Radiology suggested that places people already go to for care, such as pharmacies, federally qualified health centers, and even nonmedical environments, could be leveraged to broaden access to screening.

Health Economic Considerations

Several participants shared research insights from work aimed at elucidating the economic impacts of different scenarios for MCD test deployment and discussed how the potential costs and benefits fit within the broader context of health care spending.

___________________

31 See https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/documents/communicating-for-health/communication-framework.pdf (accessed January 16, 2025).

Ya-Chen Tina Shih from the University of California, Los Angeles provided data on the growth in the adoption of these tests across regions, including the United States, Europe, and other emerging markets, like China and South Korea. Globally, the market of MCD tests was valued at $104.5 million in 2020, increased to $567.5 million in 2023, and projected to reach $2.3 billion by 2028 (BCC Research, 2024). In 2023, hospitals represented 46 percent of the end users of MCD tests in the United States, with diagnostic laboratories and research institutions comprising the rest (BCC Research, 2024). However, despite the clear interest in these tests, many factors could influence whether their financial consequences are ultimately positive or negative. Many of the potential negative financial consequences for the health care system stem from the fact that when MCD tests are positive, follow-up procedures may be recommended that can be invasive, expensive, and potentially lead to complications, all of which have costs (Huo et al., 2019; Zhao et al., 2022). Shih noted that these consequences are also possible with standard screening regimens, however, and MCD tests can also have positive financial consequences if they achieve stage shifts, facilitate earlier diagnoses, and lower mortality rates, which can significantly reduce health care expenses (Mariotto et al., 2011, 2020; Yabroff et al., 2021).

Modeling the cost implications of the MCD testing lifetime is challenging, Shih said, stressing that understanding the economic implications requires cancer-specific models, because each cancer has its own distinct natural history, disease progression trajectory, work-up protocols, and costs. In addition, rigorous models need to consider test characteristics for each cancer along with factors such as lead time,32 length bias,33 and participation bias. Health utility calculations are also challenging because measurements of quality-adjusted life years differ dramatically depending on the cancer and stage as well as the “disutility” associated with diagnostic work ups, Shih noted.

Ramsey shared findings from his work on cost-effectiveness and budget impact analysis. For cost-effectiveness analysis, researchers quantify the costs and impacts of interventions as a ratio, often expressed as a cost per quality-adjusted life year. This ratio can be used to determine the intervention’s value or whether the incremental benefits it offers justify its cost relative to other interventions or a particular value threshold. Budget impact analysis, by con-

___________________

32 Lead-time bias occurs when screening finds a cancer earlier than it would have been diagnosed because of symptoms but the earlier diagnosis does nothing to change the course of the disease.

33 Length bias refers to how screening is more likely to detect slower-growing, less aggressive cancers, which can exist longer than fast-growing cancers before symptoms develop. See https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/screening/research/what-screening-statistics-mean (accessed February 4, 2025).

trast, focuses on the costs of implementing an intervention and associated downstream costs, with a focus on the near-term costs to insurers, and does not explicitly consider health effects. At present, Ramsey said that the value proposition for MCD testing is unclear, with important uncertainties in terms of both costs and impacts on survival. However, given the potentially substantial budget impacts of widespread adoption of these tests, it is nevertheless helpful to use cost prediction models in concert with RCT results to inform decision making around insurance coverage, eligibility, and other facets of implementation.

Researchers have used simulation models to assess cost-effectiveness and budget impacts of a variety of MCD testing scenarios with different costs and outcomes. Factors that influence model output include the eligible patient population, patient willingness and ability to undergo MCD testing, the natural history of cancers detected, screening and follow-up strategies, test performance, and health system capacity. Ramsey said that, overall, attempts to model the cost-effectiveness of MCD tests have been largely inconclusive, as results vary widely depending on assumptions around characteristics such as cost, specificity, sensitivity, cancer incidence, and cancer prevalence (Lewis et al., 2024; Lipscomb et al., 2022; Tafazzoli et al., 2022). A primary factor in determining the cost-effectiveness of MCD tests will be the per-test cost, and in terms of benefits, models indicate that the mortality impacts of MCD testing will be more economically impactful than cancer care cost savings.

Several participants discussed how there has been less research on budget impact analysis than on cost-effectiveness. To address this gap, Ramsey and colleagues developed a model combining data on standard cancer screenings, which are estimated to cost $43 billion per year (Halpern et al., 2024), with assumptions about who would undergo MCD tests and who would pay for them. The results suggested that if health insurers cover MCD tests, the large screening and follow-up costs—estimated at $25–32 billion—would not be fully offset by the roughly $1 billion in savings that would be reaped through stage shifts in cancer diagnoses. However, he added that it may be possible to mitigate the budget impact through aggressive price negotiation, further risk stratifying screening populations, and lengthening screening intervals when appropriate. Risk-informed screening—identifying subgroups who would benefit most—could reduce the budget impact but may also raise concerns around fairness, he noted. Overall, this work suggests that insurer coverage policies will be the main driver of MCD test uptake and will thereby drive the associated budget impact. While uptake is likely to be modest at current prices without insurance coverage, MCD testing is likely to be the costliest component of cancer screening in the United States if it becomes covered by insurance and widely adopted.

Pisano asked whether the budget impact analysis accounts for the cost of building out health care capacity for MCD tests and associated follow-up needs, noting that in her field, radiology, workforce capacity, and equipment availability already present significant concerns. Doubeni agreed that MCD tests need to be cost-effective, and he and Pisano suggested that there might be a different cost-benefit balance when considering the use of these tests for different purposes, such as early detection versus disease surveillance. Ramsey noted that the analysis only included the costs of follow-up processes for positive tests. He added that if the rate of positive tests were lowered, costs would go down but fewer cancers would be detected. Smith and Winn also agreed that it is important to address how implementation of MCD tests may stress the health care workforce. Karlan stressed the importance of adequate workplace capacity—especially workforce and equipment needs—to minimize delays and reduce patient and clinician stress. Shulman noted that technology can help with workforce shortages. For example, he said, augmented intelligence systems enable clinicians to work better, more efficiently, and smarter.

Beer pointed out that budget figures in the billions may seem high, but it is important to view them in the context of total health care spending, which is in the trillions (CMS, 2024). Ramsey agreed that the $43 billion spent on screening is a small portion of the $4.9 trillion health budget34 but noted that adding MCD tests could disrupt insurers’ entire budgets, even with the potential financial and health benefits. The expenses are not too high if interventions truly improve patients’ lives (i.e., are more cost-effective), he continued, but MCD tests have not yet been shown to do that. If coverage for MCD testing is offered before there is adequate evidence of their benefits, their high costs could negatively impact an insurer’s ability to cover other services, which could have detrimental impacts. Even if the tests prove effective, the implications of such a massive increase in spending are worth careful consideration, Ramsey said.

Doubeni noted that cost modeling is important for primary care clinicians because implementing MCD tests could dramatically change how primary care operates without improving outcomes, which he stated could make MCD testing a disutility. Facilitating shared decision making is important, but he said that for tests that are perceived as a disutility, it is unlikely that health systems would encourage, and support time and effort of health care personnel needed for successful implementation.

Smith noted that some health care fields are considering options for treating patients’ health more holistically. For example, a collaborative initia-

___________________

34 See https://www.cms.gov/data-research/statistics-trends-and-reports/national-health-expenditure-data/historical (accessed January 23, 2025).

tive35 of the ACS, American Heart Association,36 and American Diabetes Association,37 which all address diseases with common risk factors, emphasized that addressing overall health, with care tailored to individual patient needs, improves quality of life more than treating each disease separately. Cost modeling suggests this approach is prohibitively expensive, but Smith noted that it is still far less than other national expenditures, such as defense, and the benefit would be a reduced disease burden.

Building on this point, several participants suggested that other benefits of better health may exist that are not captured in economic models. Noting that a healthier workforce benefits the economy and all companies, Klein asked whether models accounted for the productivity benefits that might be expected when people are cured of cancer that would have led to disability and death if undetected at an early stage. Jill Hagenkord of Optum Genomics at UnitedHealth Group (UHG) agreed that companies have an interest in strategies that can increase productivity and engagement and decrease absenteeism. Ramsey replied that he had not included this aspect in his economic modeling for MCD testing but suggested that it could be incorporated into models of the social impacts.

Health Insurance and Coverage Considerations

Decisions about whether and for whom MCD testing will be covered by health insurance could have a significant impact on the trajectory of these tests in the cancer care landscape. Kathryn A. Phillips from the University of California, San Francisco said that now is the time to consider factors that will guide insurance coverage for MCD tests, before the tests are widely adopted (Deverka et al., 2022). In addition, she said that payers can use this time to model the economic implications associated with the use of these tests.