Sickle Cell Disease in Social Security Disability Evaluations: Pain and Treatment Settings (2025)

Chapter: 1 Introduction

1

Introduction

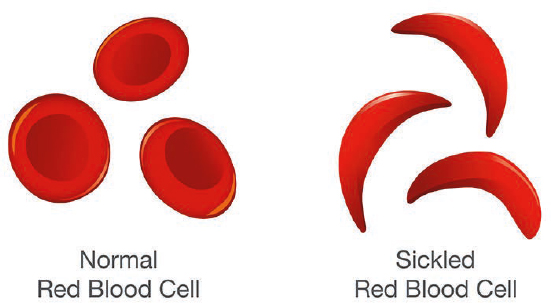

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a group of inherited blood disorders that affects approximately 100,000 people in the United States (CDC, 2024b; NHLBI, 2024). A gene mutation that causes the body to produce abnormal hemoglobin, the protein that transports oxygen in the human body, characterizes all forms of the disease. The abnormal hemoglobin causes red blood cells, which are normally disc-shaped and flexible, to become crescent- or “sickle”-shaped (NHLBI, 2024) (Figure 1-1). SCD primarily affects people of African, Mediterranean, Middle Eastern, and South Asian descent. In the United States, over 90 percent of individuals with SCD are non-Hispanic Black or African American, and an estimated 3 to 9 percent are Hispanic or Latino (CDC, 2024b; Kavanagh et al., 2022; Ojodu et al., 2014). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Sickle Cell Data Collection program, established in 2015, collects data from various sources in 16 states “to assess the long-term trends in diagnosis, treatment, and healthcare access for people with SCD in the United States” (CDC, 2024c). However, because there is no national longitudinal disease registry or surveillance program, robust national data on demographics, life course, complications, and mortality are lacking in the United States.

SCD is a chronic, life-long condition that affects every organ system in the body. The estimated life expectancy at birth for individuals with SCD in the United States is 52.6 years, more than 20 years shorter than the expected average, and quality-adjusted life expectancy, which factors in the likely quality of life as people with SCD age, is more than 30 years shorter (Jiao et al., 2023; Lubeck et al., 2019). Symptoms and SCD-associated

SOURCE: CDC, 2023.

complications, which can vary from mild to severe, include anemia; acute and chronic pain; infections; pneumonia and acute chest syndrome; stroke; cognitive dysfunction; and kidney, liver, and heart disease. For example, an individual may experience an ischemic stroke at age 3 years and require chronic transfusion therapy; another may have frequent acute pain episodes requiring emergency department visits (three or more times per year) before age 10 years, leading to chronic pain by adolescence; while up to 30 percent may only require an acute care visit once every 3 to 4 years in adulthood. This variability among individuals living with SCD adds to the complexity of the disease and its manifestations, progression, and response to treatment. Individuals with SCD often experience frequent bouts of extreme pain and hospitalization, fatigue, financial challenges resulting from lost time at work and medical expenses, and mental health concerns. The cumulative burden of all the SCD-related health effects a person living with SCD experiences can significantly affect their quality of life, including the ability of many individuals with SCD to attend and participate fully in school and work on a regular basis.

Some people with SCD may qualify for disability benefits through the Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) program (under Title II of the Social Security Act) or the Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program (Title XVI of the Social Security Act), both administered by the Social Security Administration (SSA). SSDI pays monthly benefits to eligible adults with disabilities who have paid into the Disability Insurance Trust Fund and who are unable to work because of severe long-term disabilities, as well as to their spouses and adult children. SSI is a means-tested program based on income and financial assets that provides income assistance from U.S. Treasury general funds to adults aged 65 and older, individuals who are blind, and adults and children with disabilities.

STUDY CHARGE AND SCOPE

In September 2024, SSA requested the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine to convene an ad hoc committee to review the latest published research and science and produce two reports addressing best practices and community experiences in the management and treatment of SCD, as well as recent changes or challenges in providing such care. Per the Statement of Task (Box 1-1), this report presents the committee’s findings and conclusions pertaining to objectives 3a (hospitalizations) and 3b (use of opioid pain medications in SCD). The current report also addresses objectives 2 (acute SCD [pain] crises) and 3c (interventions for SCD pain crises that are equivalent to parenteral opioid medication in terms of indicating the medical severity of the underlying acute crisis) in the Statement of Task.

The second report will present the committee’s findings and conclusions addressing all the objectives in the Statement of Task, including end-organ damage, other chronic complications of SCD, and the overall burden of the disease. At SSA’s request, the two reports contain conclusions but no recommendations. Box 1-1 presents the committee’s full Statement of Task.

BOX 1-1

Statement of Task

An ad hoc committee of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine will conduct a study to review the latest published research and science and produce a report addressing best practices and community experiences in the management and treatment of sickle cell disease (SCD). The committee’s report will

- Describe the current health care landscape for the management and treatment of SCD and its symptoms for adults and children, including traditional and alternative therapies and home remedies, their prevalence, efficacy, and side-effects, and recent changes or challenges in the provision of such care;

- Describe the typical course of an acute sickle cell crisis for adults and children, including phases of the crisis and the typical symptoms, signs, complications, functional impact, and treatment throughout the duration of the crisis, and the expected range of time to return to baseline; and

- Answer the following questions based on published evidence (to the extent possible) and professional judgment (where published evidence is lacking):

- When and how often is hospitalization used in the treatment of SCD, what factors impact the decision for a patient to present to a hospital for treatment, what factors lead to hospital staff’s

-

- decision on whether to admit a patient, what factors determine the length of hospitalization, what factors contribute to hospital readmissions within 30 days of discharge, are any of the discussed factors unique to SCD or used in a different way when making decisions related to hospitalization for individuals with SCD compared to individuals with other impairments, and how have these considerations changed over the past 10 years?

- When and how often are parenteral narcotic pain medications used to manage SCD pain crises, what are indicators or contraindicators for their use, how have best practices regarding narcotic pain medication changed over the past 10 years, and what circumstances or factors might lead providers not to prescribe narcotic pain medication even when indicated by current best practices? What other pain medications might be administered in the context of a severe pain crisis and what, if anything, can the choice of alternative medications tell us about a patient’s symptom severity?

- What treatments or interventions used for acute sickle cell crises are equivalent to parenteral narcotic medication in terms of medical severity of the underlying acute crisis (e.g., acute transfusion)?

- How and why are regular red blood cell (RBC) transfusions used differently in the treatment of SCD and beta thalassemia? What indications or thresholds, if any, would show that SCD requiring chronic RBC transfusions had an equivalent level of medical severity to beta thalassemia requiring chronic RBC transfusions?

- To what extent does end-organ damage in an individual with SCD contribute to the disease burden and overall severity of SCD, and how, if at all, does this vary by type of organ or organ-specific severity or diagnostic threshold? Might similar objective measurements of end-organ damage denote higher levels of severity or functional impact in an individual with SCD than in an individual without SCD?

The committee will prepare an interim report and a final report, both containing findings and conclusions but not recommendations. The interim report will present the committee’s findings and conclusions pertaining to objectives 3.a (hospitalizations) and 3.b (use of narcotic pain medications in SCD). The final report will present the committee’s findings and conclusions addressing all of the objectives in the Statement of Task.

TERMINOLOGY AND DEFINITIONS

Box 1-2 contains definitions of terms from the committee’s Statement of Task and others used throughout the report.

BACKGROUND AND BASICS OF SICKLE CELL DISEASE1

SCD results from a mutation in the gene that codes for hemoglobin. There are several forms of SCD, depending on the genes individuals inherit from their parents. In the most severe form of the disease, known as HbSS,

BOX 1-2

Definitions of Selected Terms

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a group of inherited red blood cell disorders in which red blood cells become sickled or crescent-shaped and sticky, which can lead to blockage of small blood vessels. In addition, the cells do not last as long as normal red blood cells, which can lead to anemia (CDC, 2025; National Cancer Institute, 2025b).

Acute sickle cell (pain) crisis (or vaso-occlusive crisis/episode) occurs when sickled red blood cells block small blood vessels, depriving tissues or organs of oxygen and resulting in pain (CDC, 2024a).

Beta thalassemia is an inherited blood disorder that limits the body’s ability to make beta-globin, which is needed to produce hemoglobin and red blood cells, and that may lead to anemia (Cleveland Clinic, 2022).

Opioid (or narcotic) pain medication refers to a class of drugs that block pain signals from the brain by activating receptors on cells located in many areas of the brain, spinal cord, and other organs in the body (National Cancer Institute, 2025a). This report preferentially uses the term “opioid” rather than “narcotic” to refer to this class of drugs because the term narcotic is less informative and is generally used in the context of law enforcement with negative connotations.

Individual (or person) with SCD refers to people who have SCD.

Caregiver refers to a person, generally a family member, who provides care to a loved one with SCD.

___________________

1 For a more complete review of SCD, please see the 2020 report Addressing Sickle Cell Disease: A Strategic Plan and Blueprint for Action (NASEM, 2020).

an individual inherits a mutated hemoglobin gene from both parents, specifically the hemoglobin S (HbS) gene, which causes the red blood cells to be stiff and to sickle. Other mutated forms of the hemoglobin gene produce abnormal hemoglobin C, hemoglobin E, hemoglobin D, and hemoglobin O, and the severity of the resulting disease varies. HbSC was once considered to be a milder form of SCD, but this is no longer the case (Nelson et al., 2024). Individuals with HbSC disease are at lower risk for some complications, such as childhood stroke and severe anemia, but at higher risk for others such as retinopathy, especially in adulthood. In addition, disease severity increases in adulthood for people with HbSC (Ghunney et al., 2023; Lionnet et al., 2012; Nelson et al., 2024).

Some individuals with SCD inherit an HbS gene from one parent and a gene for another hemoglobin abnormality known as beta thalassemia, of which there are two types, from the other parent. People who inherit the HbS gene and the gene for beta thalassemia zero (β0) tend to have a severe form of the disease (HbSβ0-thalassemia), while those who inherit the HbS gene along with the beta thalassemia plus (β+) gene tend to have a milder form of the disease (HbSβ+-thalassemia). Finally, individuals who inherit a normal hemoglobin gene from one parent and the HbS gene from the other have sickle cell trait. Sickle cell trait is usually asymptomatic, although dehydration, increased atmospheric pressure, exercising at elevation, and stress can trigger health problems, including pain crises. Children born of individuals with sickle cell trait have a 50 percent chance of inheriting the HbS gene from that parent.

SCD is diagnosed through a simple blood test, usually performed at birth during routine screening. Early diagnosis is important because children with SCD have an increased risk of developing fatal infections and other health issues. Symptoms of SCD often appear around five months of age. Since 1980, the mortality rate among children with SCD has decreased, while that for adults has increased (Payne et al., 2020). With newborn screening and the use of preventive measures such as immunizations for pneumococcal infections, prophylactic antibiotics to prevent infection, and other advances, greater than 95 percent of children with SCD in countries where such interventions are available now survive to adulthood (Quinn et al., 2010; Telfer et al., 2007).

Unique Nature of Sickle Cell Disease

Social determinants of health, defined as “the conditions in the environment where people are born, live, learn, work, play, worship, and age that affect a wide range of health, functioning, and quality-of-life outcomes and risks” (HHS, n.d.), play a significant role in shaping health outcomes for individuals with SCD, influencing both pain experiences and access to care (Khan et al., 2023). Social determinants of health such as education,

employment, social support, and health care access are tied closely to pain management in SCD (Khan et al., 2023). The terms “social drivers of health” and “social determinants of health” are often used interchangeably, with “social drivers” being preferred as it conveys that factors can be changed and influenced rather than remaining fixed. There are also structural determinants of health, defined as social, economic, and political mechanisms that generate and maintain social stratifications and, in turn, determine individual socioeconomic positions according to income, education, occupation, gender, race, and ethnicity (Broomhead and Baker, 2023). Research has linked unemployment and lower socioeconomic status to more frequent and severe pain crises, while limited access to health care services exacerbates disparities in treatment (Darby et al., 2025). In addition, individuals with SCD often experience emotional distress and social isolation, further contributing to pain perception and poorer overall health outcomes (Essien et al., 2023).

Systemic inequities and environmental factors affect disease progression and quality of life in SCD. A review found that inadequate housing, food insecurity, and inconsistent health care access disproportionately affect individuals with SCD, leading to higher rates of hospitalization and poorer long-term health outcomes (Khan et al., 2023). In health care settings, discrimination and health-related stigma further hinder effective pain management, with patients often facing delayed, inappropriate, or inadequate treatment (Blakey et al., 2023; Bulgin et al., 2018; Guarino et al., 2024; McGill et al., 2024; Miller et al., 2024). Addressing these social drivers of health is crucial to improving the well-being of individuals with SCD.

Individuals living with SCD also face challenges accessing high-quality care because of geographical, structural, and provider-level barriers (Phillips et al., 2022). Geographical barriers limit initial access to care through the limited number of comprehensive sickle cell centers, limited proximity to a specialist in rural areas, and high burdens of transportation costs (Khan et al., 2023). Data from California show that 78 percent of individuals living with SCD in the state live in urban areas and 22 percent in rural areas (Tracking California, 2025), while a cross-sectional cohort study using electronic medical records found that 88 percent of people living with SCD nationwide were living in “highly urban” areas (Olaniran et al., 2024). At the structural level, individuals report difficulty acquiring insurance coverage, identifying and finding covered providers, and facing high out-of-pocket costs such as co-pays and for medications, which affect the ability to consistently access high-quality care (Hemker et al., 2011; Huo et al., 2018; Matthie et al., 2016; Sobota et al., 2011). Limited coverage of therapies, including transfusions and prescription drugs, often compounds these challenges (Lee et al., 2019).

Even when individuals can overcome these barriers, some face providers who refuse to treat them for various reasons, including limited knowledge of the disease (Reich et al., 2023). At the provider level, individuals living

with SCD face shortages in health care providers who specialize in SCD (Kanter et al., 2020), with studies indicating that lack of provider knowledge is a significant barrier to care (Haywood et al., 2009). Given the complex and disabling effects of SCD, it is necessary to have health care providers with comprehensive education for optimal patient outcomes (Brennan-Cook et al., 2018).

Environmental determinants of health also make the experience of living with SCD more complex. Extreme changes in weather and atmosphere affect SCD (Piel et al., 2017). Climates with excessive heat and cold, such as in the southern and northern regions of the country, can trigger complications. Research also shows that high altitude and poor air quality can cause acute pain in individuals living with SCD (Piel et al., 2017; Yallop et al., 2007).

Research has identified four interdependent elements—intrinsic, sociocultural, health care, and structural factors—that shape the distinct experiences of people living with SCD (Kavanagh et al., 2022). Intrinsic factors encompass the disease burden and the psychological functioning that living with SCD influences, with the three extrinsic factors influencing these intrinsic factors. SCD affects sociocultural factors such as relationships and academic and vocational attainment (Heitzer et al., 2023; Miller et al., 2022; Osunkwo et al., 2021). Patients experience poor access to and poor quality of health care as well as stigma and bias and providers with limited knowledge about SCD and care guidelines (Lee et al., 2019). Thus, patients endure many challenges within the health care system when addressing acute crisis and hospitalizations (Lee et al., 2019; Matthie et al., 2016; Wu et al., 2024). The historically poor treatment that patients with SCD have experienced can lead to an unwillingness to seek medical care when experiencing a serious medical complication, which in turn may lead to poor outcomes (Abdallah et al., 2020; Bennett and Mulhall, 2008; NASEM, 2020).

Lastly, larger structural factors, including systemic injustice and institutionalized racism, influence the sociocultural and health care experiences of people living with SCD. Many patients with SCD report being marginalized and dismissed within the medical community when seeking care, and their outcomes have been affected by racism at a higher level than any other disease (Blakey et al., 2023; Power-Hays and McGann, 2020). In the context of care-seeking in SCD, the term “dismissed” can reflect the experience of stigma (being devalued or invalidated). Individuals living with SCD have described being dismissed from a medical practice by a hematologist/oncologist who also saw individuals with cancer because the clinician either no longer wanted to care for or did not feel comfortable caring for individuals with living with SCD (Phillips et al., 2022). Others have described feeling “less than human” when health care providers have ignored their reports of pain or discounted them as false

(Jacob and American Pain Society, 2001; Jenerette et al., 2014; Solomon, 2010; Strickland et al., 2001).

Given that most individuals with SCD in the United States are Black, they often fail to receive necessary care because of the erroneous belief of many health care providers that patients with SCD are drug seeking, even though the rate of opioid use disorder is far lower in the SCD patient population than in the general population (Blakey et al., 2023; Kissi et al., 2022; NASEM, 2020; Power-Hays and McGann, 2020; Ruta and Ballas, 2016). Therefore, patients with SCD will often avoid care in the emergency department for fear of retribution, thereby placing themselves at risk of developing more serious complications. In sum, living with SCD is a multifaceted experience that requires mindful consideration of intrinsic and extrinsic elements.

The Lived Experience

SCD is a chronic condition, and people living with SCD must be constantly aware of potential triggers of pain crises, the most common reason for seeking treatment and disability; signs of stroke, a particular concern for children; infection; anemia, resulting from the short lifespan of HbS red blood cells; and acute chest syndrome, a serious lung complication that can make breathing difficult and lead to life-threateningly low oxygen levels.

To gain a better understanding of what it is like to live with or care for someone with SCD, the Committee on Sickle Cell Disease in Social Security Disability Evaluations hosted three webinars to hear from eight individuals with SCD and two caregivers for family members with SCD. The committee also issued a Call for Perspectives, soliciting written responses to a series of questions. This process is described later in the chapter. Together, the speakers and written responses provided a powerful message about the challenges of living with SCD, including how difficult it can be to receive appropriate care from health care providers who have little understanding of SCD and its many complications.

The speakers and written responses noted that for most people living with SCD, the two most common reasons for seeking care are debilitating pain crises and acute chest syndrome, making it imperative for them to have a plan in place to address what can be excruciating pain and difficulty breathing. If pain symptoms start when away from home, the person experiencing them needs to know where the nearest hospital is and how to get there as quickly as possible in case their prescribed pain medication does not stop the crisis. Going to the hospital, though, comes with the risk of being hospitalized, often for days or even weeks, and missing school, work, or family responsibilities.

People living with SCD and caregivers note the heterogeneity and unpredictability of living with the disease.

“We have a saying in our family that states, ‘Sickle cell is not one-size-fits-all.’ We live by this statement because it’s clear that although we may all suffer from the same disease as well as the same genotype, we have all had different experiences with the disease.”

—Adult living with and parent of children living with SCD2

“Living with sickle cell disease, my life is very unpredictable . . . because I never know when something is going to happen from a drop in my hemoglobin leading to blood transfusions, infections in my body, organ damage or failure, surgeries, hospitalization from bad pain crises, and even unjust treatment when all I am doing is seeking help.”

—Adult living with SCD3

“I’m on edge every time we go somewhere because he could have a flareup at any moment.”

—Parent of a child living with SCD4

When experiencing a pain crisis severe enough to seek medical care, a person with SCD needs to be seen within 60 minutes of arrival at a health care facility per national guidelines, given the significant risk of organ damage if the episode is left untreated (Brandow et al., 2020; Yawn et al., 2014). However, depending on the facility, individuals experiencing a pain crisis, or even acute chest syndrome, can encounter a lengthy wait for care because they are “only experiencing pain.”

“The problems I experience consistently are in the emergency department—being made to wait for hours before someone comes to see me. Even after my [primary care provider] calls the desks to give orders.”

—Adult living with SCD5

“I wasn’t being listened to and my [1-year-old] son sat suffering for four hours before he was attended to and taken seriously.”

—Parent of a child with SCD6

___________________

2 Excerpt from Call for Perspectives Response.

3 Excerpt from Call for Perspectives Response.

4 Excerpt from Call for Perspectives Response.

5 Excerpt from Call for Perspectives Response.

6 Excerpt from Call for Perspectives Response.

Even after a pain crisis ends, recovering from the episode can take days or weeks. Christelle Salomon, a health policy and education analyst at the University of California San Francisco Sickle Cell Center of Excellence and a person living with SCD, called the entire experience “draining.”7 For many individuals living with SCD, the recovery period is as much about mental health as physical health (Jonassaint et al., 2024).

“I think that a lot of adults with sickle cell have been traumatized and have [posttraumatic stress disorder] from just stigma alone.”

—Teonna W., adult living with SCD8

SCD is also challenging for the families of people living with this disease. Tristan Lee, a patient advocate and person living with SCD, noted how his spouse has had to carry him from the second story of their house during a pain crisis or acute chest syndrome.9 For Nikia Vaughan, executive director of the Maryland SCD Association and caregiver for her husband and 12-year-old daughter, who both have SCD, the disease is not just about the physical aspects, for it affects every aspect of their lives.10 For example, when looking for a school for her daughter, she has to make sure the school will care for her properly. She reports that too often, when explaining what having SCD entails, doctors do not listen to her or respect her knowledge about the disease.

“I wish there was greater acknowledgment of the expertise families and patients bring to their care. We know their bodies and triggers and response better than anyone, and sometimes it feels you have to fight to be heard, to have concerns taken seriously, and build stronger partnership with providers where they truly listen, believe experiences, and show compassion. It would make a world of difference.”

—Nikia V., parent and spouse of persons living with SCD11

___________________

7 Presented at the “Hospitalization and Sickle Cell Disease – public webinar” on December 20, 2024.

8 Presented at the “Hospitalization and Sickle Cell Disease – public webinar” on December 20, 2024.

9 Presented at the “Hospitalization and Sickle Cell Disease – public webinar” on December 20, 2024.

10 Presented at the “Hospitalization and Sickle Cell Disease – public webinar” on December 20, 2024.

11 Presented at the “Hospitalization and Sickle Cell Disease – public webinar” on December 20, 2024.

“From the caregiver’s perspective as well, you know, as a mom of a child with sickle cell, and the unpredictability of hospitalizations and crises . . . I have to have some of those accommodations as well. So that literally led me to my career. I feel like my having a career that is solely focused around sickle cell also allows for some flexibility because [I am] working in an environment of people who understand what the disease is and how it impacts not just the patient but the families as well.”

—Vesha J., parent of a child living with SCD12

THE TREATMENT LANDSCAPE OF SICKLE CELL DISEASE

An increased understanding of SCD and its associated complications along with the increased longevity of people living with the disease have changed the treatment landscape for individuals living with SCD.

Meta Trends in the Care of Patients with Sickle Cell Disease

SCD is now recognized as a multisystem disorder with a variable course and possible sub-phenotypes. As one of the foregoing quotations illustrated, everyone’s experience with the disease is different, even among individuals with the same genotype. Similarly, experts in SCD now recognize that pain, the most common morbidity associated with SCD, is multifaceted; may be chronic as well as acute; and can result from causes other than ischemia-reperfusion injury with resultant inflammation and nociceptive pain, including neuropathic resulting from the remodeling of nerves and central nervous system components caused by the rewiring of connections in the brain.

A better understanding of the pathophysiology of SCD has led to the development of disease-modifying therapies that target pathophysiological pathways, with the goal of decreasing the frequency of acute pain crises and the development of chronic pain, although the effect of these therapies on the development, severity, or reversal of chronic pain is not proven. In addition to trying to minimize unscheduled acute care visits, there has been a shift in care settings from emergency department and inpatient care to home care, outpatient clinics, and infusion centers, whenever possible.

Another trend in SCD is the evolution in models of care. For decades, specialized centers have provided comprehensive services for individuals with SCD, including behavioral health care and social services, following a chronic complex disease model with holistic care. Such centers bring together a variety of health care providers with different specialties who have detailed knowledge of SCD and its potential acute and chronic effects

___________________

12 Presented at the “Functional Outcomes of Sickle Cell Disease: The Whole-Person Experience – public webinar” on February 21, 2025.

throughout the body. However, such comprehensive care centers are usually centered in urban areas, making such care difficult to access for people living in rural areas (Khan et al., 2023). It is generally acknowledged that geography and other social drivers of health play a significant role in health outcomes for individuals living with SCD (Phillips et al., 2022).

Pediatric Care Management

The care of children and adolescents with SCD has evolved over the last 50 years from a system of reacting to acute complications toward a preventive care model, with efforts in the 1980s focused on infection prevention (Gaston et al., 1986), increased attention to stroke prevention in the early 2000s (Lee et al., 2006), and then prevention of broader sickle cell complications with the use of hydroxyurea (NHLBI, 2014; Wang et al., 2011). Comprehensive sickle cell centers seek to provide holistic care for children, adolescents, and their families (Quinn et al., 2010). Ideally, pediatric patients with SCD have a primary pediatric care provider for general pediatric care and a multidisciplinary SCD medical team for SCD-specific symptomatology and complications. A modified Delphi consensus of pediatric SCD specialists determined the following essential elements for a comprehensive pediatric SCD center team: an SCD physician expert, a pediatric hematology team for inpatient care, outpatient nursing staff with SCD expertise, a case manager, a social worker, and an education liaison, such as a social worker, neuropsychologist, teacher, or nurse (Hulbert et al., 2023). Standardized processes such as newborn screening follow-up, protocols for acute and chronic care and emergency department care, standardized order sets in the electronic medical record for pain admissions, transition to an adult care program, and a formal process for patient/family input were identified as essential to the provision of guideline-based care. Most SCD centers providing this level of comprehensive care are large academic children’s hospitals. Between 2016 and 2018, 13 to 24 percent of children and adolescents with SCD never saw a hematologist, potentially missing out on the interventions demonstrated to reduce morbidity and mortality (Horiuchi et al., 2022). Innovative service delivery options, such as telemedicine and primary care partnerships, are needed to reach patients and families in rural areas.

Adult Medical Care Team Management

With improved pediatric care, most people with SCD now live to adulthood (Quinn et al., 2010), necessitating the development of models of care geared toward adults with the disease. This transition is fraught with complications stemming from increased independence from caregivers, challenges navigating insurance and health systems, and a paucity of SCD

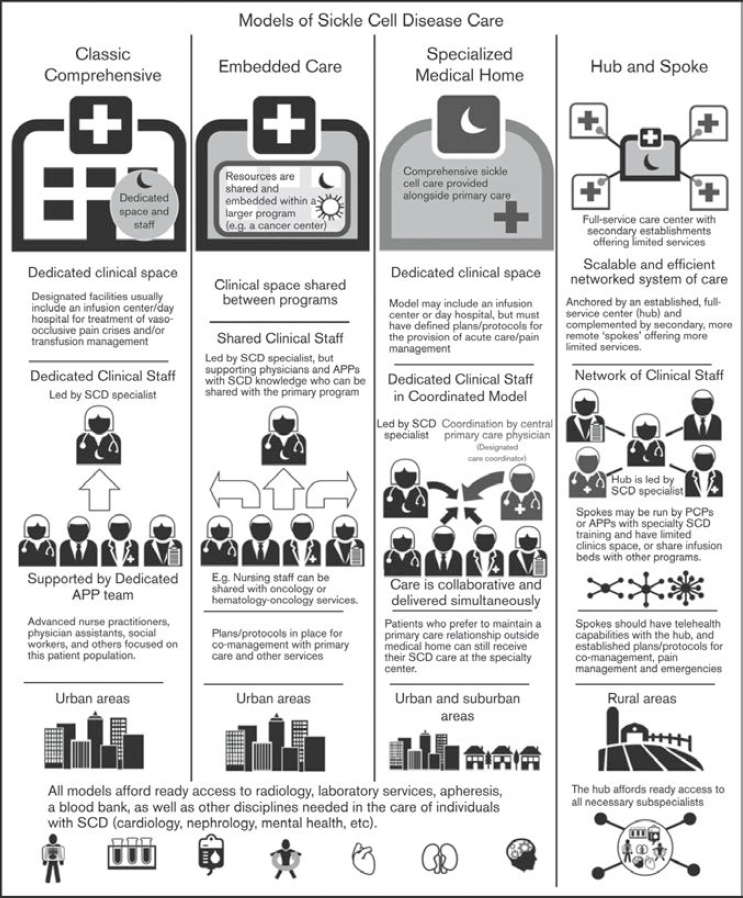

clinicians (NASEM, 2020; Sobota et al., 2011). Young adults with SCD report there are additional barriers for this population related to decreased compassion by doctors and nurses related to perceived racial discrimination (Prussien et al., 2022). While there are dedicated pediatric centers embedded in hematology/oncology departments, with resources for behavioral health and medical treatment, these are lacking for adults in many areas around the country (Kanter et al., 2020). Building access to care in adult SCD includes instituting models of care, determining the essential components in a program, and considering economic factors, all of which contribute to the challenges of adult medical care (Kanter et al., 2020). In 2020, leading SCD experts collaborated and published guidelines for models of care for SCD treatment, offering programs knowledge about how to best initiate care models that fit their needs (Brandow et al., 2020). Figure 1-2 summarizes four examples of successful models of care for adults with SCD.

The Classic Comprehensive Program is led by an SCD specialist located in an urban area, supported by a dedicated advanced practice provider, social workers, and others focused on the SCD patient population. The care team has dedicated clinic space and typically an infusion center/day hospital for vaso-occlusive pain crisis treatment, transfusion management, or both.

The Embedded Care Model shares clinical staff and is also located in an urban area. In this model, the SCD clinic shares resources and is embedded in a larger program, typically a cancer center, with those programs sharing the space. It is led by an SCD specialist, but it also has knowledgeable and dedicated SCD staff, who can be shared with primary care. Plans and protocols are in place for co-management with primary care and other services.

The Specialized Medical Home Model provides comprehensive SCD care alongside a primary care provider and is located both in urban and suburban areas. This model has dedicated clinic space and may include an infusion program/day hospital but must have a defined protocol/plans for providing acute pain management. The dedicated SCD provider coordinates primary care with simultaneous collaborative care delivery. If a patient prefers to maintain a primary care relationship outside the medical home, they can still receive their SCD care at the specialty center.

The Hub and Spoke Model is based in a full-service center with secondary establishments offering limited services. This model includes a network of clinical staff, with the hub providing ready access to all necessary subspecialists. Anchored by a full-time hub and complemented by secondary, remote spokes that offer more limited services, this model is typically run by an advanced practice provider or primary care physician with specialty training in SCD but has limited clinical space and shares infusion beds with other programs.

Even with the guidelines for care, a variety of challenges remain, including a shortage of trained adult SCD experts around the country, limited knowledge about SCD by emergency department physicians, and rural

NOTE: APP = advanced practice provider; PCP = primary care physician; SCD = sickle cell disease.

SOURCE: Kanter et al., 2020. © The American Society of Hematology, used with permission.

areas that limit access to best care for many patients (Masese et al., 2019; Phillips et al., 2022). However, these models of care have played a significant role in assisting new programs in developing standardized care to better address the importance of standard practice of care and quality of care for patients living with SCD.

SOURCE: SSA, 2024a, pp. 2-3.

SOCIAL SECURITY ADMINISTRATION DISABILITY EVALUATION PROCESS13

For adults, “disability” is defined by statute as the “inability to engage in substantial gainful activity [defined by an earnings threshold] by reason of any medically determinable physical or mental impairment which can be expected to result in death or has lasted or can be expected to last for a continuous period of not less than 12 months.”14 SSA considers children under age 18 to be disabled if they have “a medically determinable physical or mental impairment, which results in marked and severe functional limitations, and which can be expected to result in death or which has lasted or can be expected to last for a continuous period of not less than 12 months.”15 A finding of disability in both adults and children depends on the severity of functional limitations arising from the claimant’s impairment or combination of impairments.

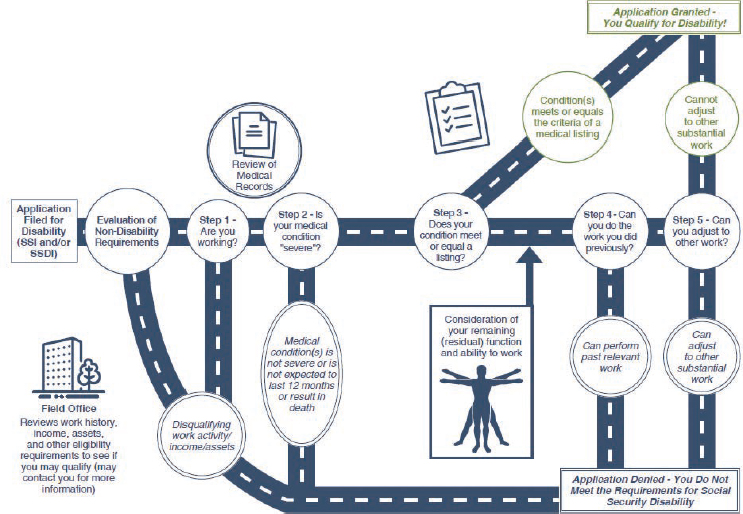

SSA uses a five-step process based on medical–vocational evaluations to determine whether an adult meets the definition of disability (Figure 1-3). After SSA determines an applicant’s administrative eligibility and the

___________________

13 This section is taken largely from NASEM, 2022, pp. 13-15.

14 42 USC § 416(i). This sentence was changed after release of the report to correct the definition of adult disability according to statute 42 USC § 416(i).

15 42 USC § 1382c.

presence of a medical impairment of sufficient duration and severity in steps 1 and 2 of this process, it assesses in step 3 whether the applicant’s impairment meets or medically equals the criteria listed for a condition in SSA’s Listing of Impairments—Adult Listings (SSA, n.d.-a). The Adult Listings are organized by major body system and describe impairments that SSA considers to be sufficiently severe to prevent an applicant from performing any gainful activity, regardless of age, education, or work experience.

Step 3 is used as a “screen-in” step, meaning if an individual does not qualify for disability benefits at this step, they are not denied, and the assessment moves to step 4. If an impairment is severe but does not meet or medically equal any listing, SSA assesses in step 4 whether the applicant’s physical or mental residual functional capacity allows the person to perform past relevant work. Applicants who are able to perform past relevant work are denied benefits, while those who are unable to do so proceed to step 5. At step 5, SSA considers an applicant’s residual functional capacity along with vocational factors such as age, education, and work experience, including transferable skills, in determining whether the individual can perform other work in the national economy. Applicants determined to be unable to adjust to performing other work are allowed benefits, while those determined able to adjust are denied.

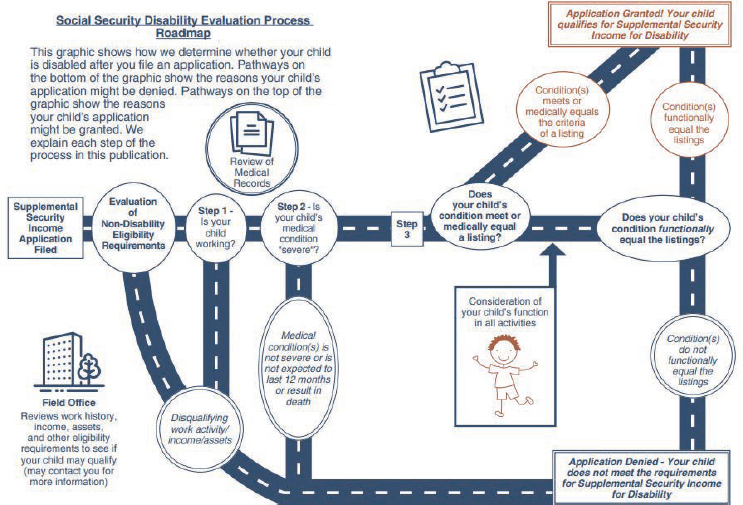

Disability determinations in children follow a three-step sequential evaluation process (Figure 1-4). After determining administrative eligibility and the presence of a medical impairment of sufficient duration and severity,

SOURCE: SSA, 2024b, pp. 3–4.

SSA assesses in step 3 whether the impairment(s) meets or medically equals (is equivalent in severity to) the criteria in any of SSA’s Childhood Listings (SSA, n.d.-b), or functionally equals (i.e., the impairment[s] results in functional limitations equivalent in severity to) the Childhood Listings.

For both adults and children, listing criteria specific to hemolytic anemias, including SCD, are found under the listings for Hematological Disorders.16

SOCIAL SECURITY ADMINISTRATION’S CURRENT LISTINGS FOR SICKLE CELL DISEASE

The Hematological Disorders listings for both children and adults specify medical criteria that apply to the evaluation of SCD at step 3 of SSA’s disability determination processes (SSA, n.d.-a, 7.00; n.d.-b, 107.00). However, if an applicant’s condition does not meet any of the listings in the hematological body system, SSA will consider whether it satisfies the listing criteria in another body system (SSA, 2024a,b).

Children with Sickle Cell Disease

At step 3 of the disability determination process for children with SCD, SSA evaluates whether the child’s impairment(s) meets or medically equals the criteria of any listing, or functionally equals the listing. When determining whether a child’s condition(s) functionally equals the severity of the listings, SSA considers six different areas of functioning:

- moving about and manipulating objects,

- acquiring and using information,

- attending and completing tasks,

- interacting and relating with others,

- caring for [oneself], and

- health and physical well-being.17

As described in Sickle Cell Disease and the Social Security Disability Evaluation Process for Children, the listing criteria for SCD in the hematological body system include the following:

- Listing 107.05A—[SCD] with 6 documented painful crises in 1 year, each requiring intravenous (IV) or intra-muscular (IM) [opioid] medication, and each crisis at least 30 days apart.

___________________

16 The Hematological Disorders listings for adults are available at https://www.ssa.gov/disability/professionals/bluebook/7.00-HematologicalDisorders-Adult.htm (accessed March 13, 2025). Those for children are available at https://www.ssa.gov/disability/professionals/bluebook/107.00-HematologicalDisorders-Childhood.htm (accessed March 13, 2025).

17 20 CFR 416.926a.

- Listing 107.05B—[SCD] with complications requiring 3 hospitalizations in 1 year, each 30 days apart and each lasting at least 48 hours.

- Listing 107.05C—[SCD] with blood tests showing hemoglobin values at or below 7.0 grams per deciliter (g/dL), measured at least 3 times in 1 year and at least 30 days apart.

- Listing 107.17—[SCD] treated with bone marrow or stem cell transplantation. (SSA, 2024b)

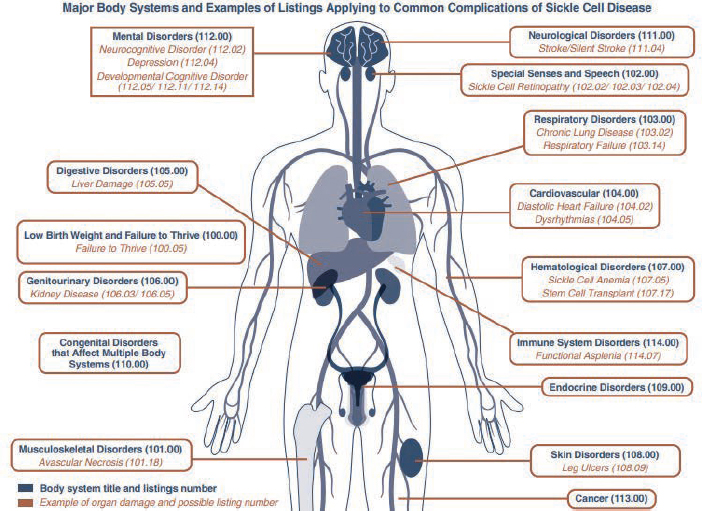

If a child’s condition(s) does not meet or medically equal any of these listings, they might still satisfy the listing criteria in another body system. Figure 1-5 depicts other body systems and examples of listings that may apply to common complications of SCD.

Adults with Sickle Cell Disease

SSA considers people aged 18 and older to be adults. When a child with SCD who has been receiving disability benefits turns 18, they become an adult for SSA’s purposes and must requalify for benefits under SSA’s five-step disability determination process for adults.

SOURCE: SSA, 2024b, pp. 13-14.

At step 3 of the adult determination process, SSA evaluates whether an individual’s condition meets or medically equals the listing criteria for adults. Most of the listing criteria for adults with SCD in the hematological body system are the same as those listed above for children, albeit with different numberings (Listings 7.05A, 7.05B, 7.05C, and 7.17). However, the adult listing criteria include a fifth listing:

- Listing 7.18–repeated complications of [SCD] causing significant documented symptoms or signs (for example, pain, severe fatigue, malaise, fever, night sweats, headaches, joint or muscle swelling or shortness of breath), AND marked limitations in one area of functioning (activities of daily living, maintaining social functioning, or completing tasks in a timely manner because of deficiencies in concentration, persistence, or pace). (SSA, 2024a)

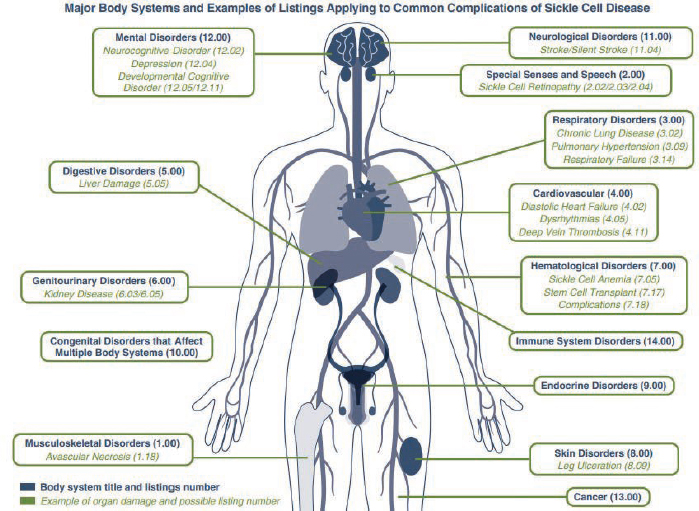

As with children, if an adult’s condition(s) does not meet or medically equal any of these listings, it might still satisfy the listing criteria in another body system. Figure 1-6 depicts other body systems and examples of listings for adults that may apply to common complications of SCD.

SOURCE: SSA, 2024a, pp. 12-13.

If the individual’s condition does not meet or medically equal any of the listing criteria for adults, SSA will assess their “residual functional capacity” and compare it with the demands of past relevant or other work at steps 4 and 5 of the disability determination process.

STUDY APPROACH

The committee met three times in closed session to discuss the questions posed in the Statement of Task. The committee also hosted three public information-gathering webinars on topics relevant to the Statement of Task (see Appendix A). Each webinar comprised two panels: one panel of subject matter experts, including one person living with SCD, and another panel of individuals with lived experience with SCD, including individuals living with the disease and caregivers. The first webinar focused on hospitalization and SCD, the second focused on pain management and SCD, and the third focused on functional outcomes of SCD and the whole-person experience. The committee also issued a Call for Perspectives to solicit information from individuals with SCD and caregivers on the following topics:

- Their experiences living with or caring for someone with SCD.

- Their experiences with acute pain/SCD crises and the typical course of a crisis for them.

- The ways in which they manage pain and other symptoms associated with SCD at home, including traditional and alternative therapies and home remedies, and how it has changed over time.

- If applicable, the factors that contribute to their decision to seek care in a hospital or other medical facility for treatment of SCD, including any barriers they might face in accessing care.

- Any current and past effects of SCD on their day-to-day physical and mental health functioning. For example, does living with SCD affect their ability to engage in school or full-time work?

- The overall burden of living with SCD and how it may have changed over time.

- If relevant, their experience applying for disability benefits for SCD through SSA.

- Any additional information or lived experience relevant to the Statement of Task they wanted the committee to consider.

The committee received 10 responses to the Call for Perspectives: five from individuals with SCD, including one who also is a parent/caretaker of children with the disease and one who is a head of community-based organization, plus four without SCD who are parents/caregivers and one leader of a community-based organization who is neither a caregiver nor living with SCD.

For each of the specific questions in the Statement of Task, staff aided committee members in conducting literature searches. The committee members discussed objectives 2, 3a, 3b, and 3c in the Statement of Task and reached consensus on conclusions based on published evidence, information gathered during the webinars and Call for Perspectives, and their own professional judgment where published evidence was lacking.

ORGANIZATION OF THE REPORT

Chapter 2 provides an overview of pain in SCD, including acute pain crises (objective 2 from the Statement of Task). Chapter 3 addresses pain management in SCD, including traditional, alternative, and home therapies, as well as opioid and non-opioid pain medications (objectives 3b and 3c from the Statement of Task). Chapter 4 discusses the use of various health care settings, including hospitalization, in the treatment of SCD (objective 3a from the Statement of Task). Chapter 5 contains the committee’s overarching conclusions and supporting text.

REFERENCES

Abdallah, K., A. Buscetta, K. Cooper, J. Byeon, A. Crouch, S. Pink, C. Minniti, and V. L. Bonham. 2020. Emergency department utilization for patients living with sickle cell disease: Psychosocial predictors of health care behaviors. Annals of Emergency Medicine 76(3S):S56–S63.

Bennett, N., and J. Mulhall. 2008. Sickle cell disease status and outcomes of African-American men presenting with priapism. The Journal of Sexual Medicine 5(5):1244–1250.

Blakey, A. O., C. Lavarin, A. Brochier, C. M. Amaro, J. S. Eilenberg, P. L. Kavanagh, A. Garg, M.-L. Drainoni, and K. A. Long. 2023. Effects of experienced discrimination in pediatric sickle cell disease: Caregiver and provider perspectives. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 10(6):3095–3106.

Brandow, A. M., C. P. Carroll, S. Creary, R. Edwards-Elliott, J. Glassberg, R. W. Hurley, A. Kutlar, M. Seisa, J. Stinson, J. J. Strouse, F. Yusuf, W. Zempsky, and E. Lang. 2020. American Society of Hematology 2020 guidelines for sickle cell disease: Management of acute and chronic pain. Blood Advances 4(12):2656–2701.

Brennan-Cook, J., E. Bonnabeau, R. Aponte, C. Augustin, and P. Tanabe. 2018. Barriers to care for persons with sickle cell disease. Professional Case Management 23(4):213–219.

Broomhead, T., and S. R. Baker. 2023. From micro to macro: Structural determinants and oral health. Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology 51(1):85–88.

Bulgin, D., P. Tanabe, and C. Jenerette. 2018. Stigma of sickle cell disease: A systematic review. Issues in Mental Health Nursing 39(8):675–686.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2023. What is sickle cell disease? https://archive.cdc.gov/www_cdc_gov/ncbddd/sicklecell/features/what-is-scd.html (accessed April 8, 2025).

CDC. 2024a. Complications of SCD: Pain. https://www.cdc.gov/sickle-cell/complications/pain.html (accessed March 14, 2025).

CDC. 2024b. Data and statistics on sickle cell disease. https://www.cdc.gov/sickle-cell/data/index.html (accessed January 13, 2025).

CDC. 2024c. Sickle Cell Data Collection (SCDC) program. https://www.cdc.gov/sickle-cell/scdc/index.html (accessed April 21, 2025).

CDC. 2025. About sickle cell disease (SCD). https://www.cdc.gov/sickle-cell/about/index.html (accessed April 23, 2025).

Cleveland Clinic. 2022. Beta thalassemia. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/23574-beta-thalassemia (accessed March 14, 2025).

Darby, J. E., I. C. Akpotu, D. Wi, S. Ahmed, A. Z. Doorenbos, and S. Lofton. 2025. A scoping review of social determinants of health and pain outcomes in sickle cell disease. Pain Management Nursing 26(1):e1–e9.

Essien, E. A., B. F. Winter-Eteng, C. U. Onukogu, D. D. Nkangha, and F. M. Daniel. 2023. Psychosocial challenges of persons with sickle cell anemia: A narrative review. Medicine (Baltimore) 102(47):e36147.

Gaston, M. H., J. I. Verter, G. Woods, C. Pegelow, J. Kelleher, G. Presbury, H. Zarkowsky, E. Vichinsky, R. Iyer, J. S. Lobel, S. Diamond, C. T. Holbrook, F. M. Gill, K. Ritchey, and J. M. Falletta. 1986. Prophylaxis with oral penicillin in children with sickle cell anemia. New England Journal of Medicine 314(25):1593–1599.

Ghunney, W. K., E. V. Asare, J. B. Ayete-Nyampong, S. A. Oppong, M. Rodeghier, M. R. Debaun, and E. Olayemi. 2023. Most adults with severe HbSC disease are not treated with hydroxyurea. Blood Advances 7(13):3312–3319.

Guarino, S., O. Bakare, C. Jenkins, K. Williams, K. Subedi, C. Wright, L. Pachter, and S. Lanzkron. 2024. Attitudes and beliefs regarding pain and discrimination among Black adults with sickle cell disease: A mixed methods evaluation of an adapted chronic pain intervention. Journal of Pain Research 17:3601–3618.

Haywood, C., Jr., M. C. Beach, S. Lanzkron, J. J. Strouse, R. Wilson, H. Park, C. Witkop, E. B. Bass, and J. B. Segal. 2009. A systematic review of barriers and interventions to improve appropriate use of therapies for sickle cell disease. Journal of the National Medical Association 101(10):1022–1033.

Heitzer, A. M., V. I. Okhomina, A. Trpchevska, E. MacArthur, J. Longoria, B. Potter, D. Raches, A. Johnson, J. S. Porter, G. Kang, and J. S. Hankins. 2023. Social determinants of neurocognitive and academic performance in sickle cell disease. Pediatric Blood & Cancer 70(5):e30259.

Hemker, B. G., D. C. Brousseau, K. Yan, R. G. Hoffmann, and J. A. Panepinto. 2011. When children with sickle-cell disease become adults: Lack of outpatient care leads to increased use of the emergency department. American Journal of Hematology 86(10):863–865.

HHS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). n.d. Social determinants of health. https://odphp.health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health (accessed March 26, 2025).

Horiuchi, S. S., M. Zhou, A. Snyder, and S. T. Paulukonis. 2022. Hematologist encounters among Medicaid patients who have sickle cell disease. Blood Advances 6(17):5128–5131.

Hulbert, M. L., D. Manwani, E. R. Meier, O. A. Alvarez, R. C. Brown, M. U. Callaghan, A. D. Campbell, T. D. Coates, M. J. Frei-Jones, J. S. Hankins, M. M. Heeney, L. L. Hsu, J. D. Lebensburger, C. T. Quinn, N. Shah, K. Smith-Whitley, C. Thornburg, and J. Kanter. 2023. Consensus definition of essential, optimal, and suggested components of a pediatric sickle cell disease center. Pediatric Blood & Cancer 70(1):e29961.

Huo, J., H. Xiao, M. Garg, C. Shah, D. Wilkie, and A. Mainous III. 2018. The economic burden of sickle cell disease in the United States. Value in Health 21:S108.

Jacob, E., and American Pain Society. 2001. Pain management in sickle cell disease. Pain Management Nursing 2(4):121–131.

Jenerette, C. M., C. A. Brewer, and K. I. Ataga. 2014. Care seeking for pain in young adults with sickle cell disease. Pain Management Nursing 15(1):324–330.

Jiao, B., K. M. Johnson, S. D. Ramsey, M. A. Bender, B. Devine, and A. Basu. 2023. Long-term survival with sickle cell disease: A nationwide cohort study of Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries. Blood Advances 7(13):3276–3283.

Jonassaint, C. R., E. Parchuri, J. A. O’Brien, C. M. Lalama, J. Lin, S. M. Badawy, M. E. Hamm, J. Stinson, C. Lalloo, C. P. Carroll, S. L. Saraf, V. R. Gordeuk, R. Cronin, N. Shah, S. M. Lanzkron, D. Liles, C. Trimnell, L. Bailey, R. H. Lawrence, and K. Z. Abebe. 2024. Mental health, pain and likelihood of opioid misuse among adults with sickle cell disease. British Journal of Haematology 204(3):1029–1038.

Kanter, J., W. R. Smith, P. C. Desai, M. Treadwell, B. Andemariam, J. Little, D. Nugent, S. Claster, D. G. Manwani, J. Baker, J. J. Strouse, I. Osunkwo, R. W. Stewart, A. King, L. M. Shook, J. D. Roberts, and S. Lanzkron. 2020. Building access to care in adult sickle cell disease: Defining models of care, essential components, and economic aspects. Blood Advances 4(16):3804–3813.

Kavanagh, P. L., T. A. Fasipe, and T. Wun. 2022. Sickle cell disease: A review. JAMA Open Network 328(1):57–68.

Khan, H., M. Krull, J. S. Hankins, W. C. Wang, and J. S. Porter. 2023. Sickle cell disease and social determinants of health: A scoping review. Pediatric Blood & Cancer 70(2):e30089.

Kissi, A., D. M. L. Van Ryckeghem, P. Mende-Siedlecki, A. Hirsh, and T. Vervoort. 2022. Racial disparities in observers’ attention to and estimations of others’ pain. Pain 163(4):745–752.

Lee, M. T., S. Piomelli, S. Granger, S. T. Miller, S. Harkness, D. J. Brambilla, and R. J. Adams. 2006. Stroke Prevention Trial in Sickle Cell Anemia (STOP): Extended follow-up and final results. Blood 108(3):847–852.

Lee, L., K. Smith-Whitley, S. Banks, and G. Puckrein. 2019. Reducing health care disparities in sickle cell disease: A review. Public Health Reports 134(6):599–607.

Lionnet, F., N. Hammoudi, K. S. Stojanovic, V. Avellino, G. Grateau, R. Girot, and J. P. Haymann. 2012. Hemoglobin sickle cell disease complications: A clinical study of 179 cases. Haematologica 97(8):1136–1141.

Lubeck, D., I. Agodoa, N. Bhakta, M. Danese, K. Pappu, R. Howard, M. Gleeson, M. Halperin, and S. Lanzkron. 2019. Estimated life expectancy and income of patients with sickle cell disease compared with those without sickle cell disease. JAMA Network Open 2(11):e1915374.

Masese, R. V., D. Bulgin, C. Douglas, N. Shah, and P. Tanabe. 2019. Barriers and facilitators to care for individuals with sickle cell disease in central North Carolina: The emergency department providers’ perspective. PLOS One 14(5):e0216414.

Matthie, N., J. Hamilton, D. Wells, and C. Jenerette. 2016. Perceptions of young adults with sickle cell disease concerning their disease experience. Journal of Advanced Nursing 72(6):1441–1451.

McGill, L. S., M. L. Sánchez González, S. M. Bediako, S. M. Lanzkron, L. Yu, M. C. Beach, and C. M. Campbell. 2024. Impact of disease- and race-based discrimination in health care on pain outcomes among adults living with sickle cell disease in the United States: The mediating roles of internalized stigma and depressive symptoms. Stigma and Health. https://doi.org/10.1037/sah0000581 [Epub ahead of print].

Miller, M., R. Landsman, J. P. Scott, and A. K. Heffelfinger. 2022. Fostering equity in education and academic outcomes in children with sickle cell disease. The Clinical Neuropsychologist 36(2):245–263.

Miller, M. M., A. Kissi, D. D. Rumble, A. T. Hirsh, T. Vervoort, L. E. Crosby, A. Madan-Swain, J. Lebensburger, A. M. Hood, and Z. Trost. 2024. Pain-related injustice appraisals, sickle cell stigma, and racialized discrimination in the youth with sickle cell disease: A preliminary investigation. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40615-024-02247-y [Epub ahead of print].

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2020. Addressing sickle cell disease: A strategic plan and blueprint for action. Edited by M. McCormick, H. A. Osei-Anto, and R. M. Martinez. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NASEM. 2022. Selected heritable disorders of connective tissue and disability. Edited by P. A. Volberding, C. M. Spicer, T. Cartaxo, and R. A. Wedge. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

National Cancer Institute. 2025a. Opioid. NCI dictionary of cancer terms. https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/opioid (accessed April 8, 2025).

National Cancer Institute. 2025b. Sickle cell disease. https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/sickle-cell-disease (accessed March 14, 2025).

Nelson, M., L. Noisette, N. Pugh, V. Gordeuk, L. L. Hsu, T. Wun, N. Shah, J. Glassberg, A. Kutlar, J. S. Hankins, A. A. King, D. Brambilla, and J. Kanter. 2024. The clinical spectrum of HbSC sickle cell disease—Not a benign condition. British Journal of Haematology 205(2):653–663.

NHLBI (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute). 2014. Evidence-based management of sickle cell disease. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/evidence-based-management-sickle-cell-disease (accessed April 10, 2025).

NHLBI. 2024. Sickle cell disease: What is sickle cell disease? https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/sickle-cell-disease (accessed April 8, 2025).

Ojodu, J., M. M. Hulihan, S. N. Pope, and A. M. Grant. 2014. Incidence of sickle cell trait—United States, 2010. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 63(49):1155–1158.

Olaniran, K., A. C. Nero, and R. Turer. 2024. Sickle cell disease prevalence, social vulnerability, and rural-urban commuting area: A national snapshot from electronic medical data. Blood 144(Supplement 1):5353.

Osunkwo, I., B. Andemariam, C. P. Minniti, B. P. D. Inusa, F. El Rassi, B. Francis-Gibson, A. Nero, C. Trimnell, M. R. Abboud, J. B. Arlet, R. Colombatti, M. de Montalembert, S. Jain, W. Jastaniah, E. Nur, M. Pita, L. DeBonnett, N. Ramscar, T. Bailey, O. Rajkovic-Hooley, and J. James. 2021. Impact of sickle cell disease on patients’ daily lives, symptoms reported, and disease management strategies: Results from the international Sickle Cell World Assessment Survey (SWAY). American Journal of Hematology 96(4):404–417.

Payne, A. B., J. M. Mehal, C. Chapman, D. L. Haberling, L. C. Richardson, C. J. Bean, and W. C. Hooper. 2020. Trends in sickle cell disease-related mortality in the United States, 1979 to 2017. Annals of Emergency Medicine 76(3S):S28–S36.

Phillips, S., Y. Chen, R. Masese, L. Noisette, K. Jordan, S. Jacobs, L. L. Hsu, C. L. Melvin, M. Treadwell, N. Shah, P. Tanabe, and J. Kanter. 2022. Perspectives of individuals with sickle cell disease on barriers to care. PLOS One 17(3):e0265342.

Piel, F. B., S. Tewari, V. Brousse, A. Analitis, A. Font, S. Menzel, S. Chakravorty, S. L. Thein, B. Inusa, P. Telfer, M. de Montalembert, G. W. Fuller, K. Katsouyanni, and D. C. Rees. 2017. Associations between environmental factors and hospital admissions for sickle cell disease. Haematologica 102(4):666–675.

Power-Hays, A., and P. T. McGann. 2020. When actions speak louder than words – Racism and sickle cell disease. New England Journal of Medicine 383(20):1902–1903.

Prussien, K. V., H. L. Faust, K. Smith-Whitley, L. P. Barakat, and L. A. Schwartz. 2022. Barriers to transition from pediatric to adult care in adolescents and young adults with sickle cell disease: A mixed-method study on the impact of systems of inequity. Blood 140(Supplement 1):2173–2174.

Quinn, C. T., Z. R. Rogers, T. L. McCavit, and G. R. Buchanan. 2010. Improved survival of children and adolescents with sickle cell disease. Blood 115(17):3447–3452.

Reich, J., M. A. Cantrell, and S. C. Smeltzer. 2023. An integrative review: The evolution of provider knowledge, attitudes, perceptions and perceived barriers to caring for patients with sickle cell disease 1970–now. Journal of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology Nursing 40(1):43–64.

Ruta, N. S., and S. K. Ballas. 2016. The opioid drug epidemic and sickle cell disease: Guilt by association. Pain Medicine 17(10):1793–1798.

Sobota, A., E. J. Neufeld, P. Sprinz, and M. M. Heeney. 2011. Transition from pediatric to adult care for sickle cell disease: Results of a survey of pediatric providers. American Journal of Hematology 86(6):512–515.

SSA (Social Security Administration). 2024a. Sickle cell disease and the Social Security disability evaluation process for adults. https://www.ssa.gov/pubs/EN-60-003.pdf (accessed April 8, 2025).

SSA. 2024b. Sickle cell disease and the Social Security disability evaluation process for children. https://www.ssa.gov/pubs/EN-60-004.pdf (accessed April 8, 2025).

SSA. n.d.-a. Disability evaluation under Social Security – Listing of impairments – Adult listings (Part A). https://www.ssa.gov/disability/professionals/bluebook/AdultListings.htm (accessed March 14, 2025).

SSA. n.d.-b. Disability evaluation under Social Security – Listing of impairments – Childhood listings (Part B). https://www.ssa.gov/disability/professionals/bluebook/ChildhoodListings.htm (accessed March 14, 2025).

Solomon, L. R. 2010. Pain management in adults with sickle cell disease in a medical center emergency department. Journal of the National Medical Association 102(11):1025–1032.

Strickland, O. L., G. Jackson, M. Gilead, D. B. McGuire, and S. Quarles. 2001. Use of focus groups for pain and quality of life assessment in adults with sickle cell disease. Journal of the National Black Nurses Association 12(2):36–43.

Telfer, P., P. Coen, S. Chakravorty, O. Wilkey, J. Evans, H. Newell, B. Smalling, R. Amos, A. Stephens, D. Rogers, and F. Kirkham. 2007. Clinical outcomes in children with sickle cell disease living in England: A neonatal cohort in East London. Haematologica 92(7):905–912.

Tracking California. 2025. Sickle cell disease. https://trackingcalifornia.org/topics/sickle-cell-disease#gsc.tab=0 (accessed April 28, 2025).

Wang, W. C., R. E. Ware, S. T. Miller, R. V. Iyer, J. F. Casella, C. P. Minniti, S. Rana, C. D. Thornburg, Z. R. Rogers, R. V. Kalpatthi, J. C. Barredo, R. C. Brown, S. A. Sarnaik, T. H. Howard, L. W. Wynn, A. Kutlar, F. D. Armstrong, B. A. Files, J. C. Goldsmith, M. A. Waclawiw, X. Huang, B. W. Thompson, and BABY HUG Investigators. 2011. Hydroxycarbamide in very young children with sickle-cell anaemia: A multicentre, randomised, controlled trial (BABY HUG). The Lancet 377(9778):1663–1672.

Wu, J. K., K. McVay, K. M. Mahoney, F. A. Sayani, A. H. Roe, and M. Cebert. 2024. Experiences with healthcare navigation and bias among adult women with sickle cell disease: A qualitative study. Quality of Life Research 33(12):3459–3467.

Yallop, D., E. R. Duncan, E. Norris, G. W. Fuller, N. Thomas, J. Walters, M. C. Dick, S. E. Height, S. L. Thein, and D. C. Rees. 2007. The associations between air quality and the number of hospital admissions for acute pain and sickle-cell disease in an urban environment. British Journal of Haematology 136(6):844–848.

Yawn, B. P., G. R. Buchanan, A. N. Afenyi-Annan, S. K. Ballas, K. L. Hassell, A. H. James, L. Jordan, S. M. Lanzkron, R. Lottenberg, W. J. Savage, P. J. Tanabe, R. E. Ware, M. H. Murad, J. C. Goldsmith, E. Ortiz, R. Fulwood, A. Horton, and J. John-Sowah. 2014. Management of sickle cell disease: Summary of the 2014 evidence-based report by expert panel members. JAMA 312(10):1033–1048.