Affordable Cleanup?: Opportunities for Cost Reduction in the Decontamination and Decommissioning of the Nation's Uranium Enrichment Facilities (1996)

Chapter: G: NUCLEAR CRITICALITY

Appendix G Nuclear Criticality

Much of the uranium deposits to be removed from the U.S. gaseous diffusion plant (GDP) cascades will be enriched in uranium-235 (235 U); at Oak Ridge and at Portsmouth GDPs, some will be highly enriched, perhaps 90 percent 235U. There is the potential for a nuclear criticality accident with enriched material, a well-recognized safety problem. In a nuclear criticality event, an assemblage of enriched uranium results in a self-sustaining chain reaction, generating large amounts of heat, radioactive fission products, and gamma and neutron radiation. The burst of neutrons that occurs can be lethal to anyone exposed.

U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Order 5480.24 has established a requirement of a low probability of criticality events, less than 10-6/yr. Operating standards have been established to avoid the problem (ANS, 1983), and general administrative practices have been outlined. The increase in costs associated with these requirements should be recognized.

Accidents have occurred in spite of the safeguards, generally because people improvise during the job, moving outside of the safety limits. Of interest to the decontamination and decommissioning (D&D) of the GDPs is that most accidents have occurred during cleanup operations.

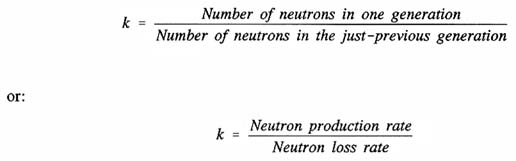

A chain reaction such as the fission of 235U to release energy is triggered by the reaction of the 235U nucleus with a neutron of the proper energy level. The reaction can be characterized by a multiplication factor:

If k = 1, the system is critical; if k < 1, the system is subcritical; and if k > 1, the system is supercritical. A subcritical system releases very little energy, while a critical or supercritical system can release very large amounts of energy and nuclear particles such as neutrons.

Production And Loss of Neutrons

Criticality depends on the rates of generation and loss of neutrons. Production of neutrons depends on the following factors:

- The nature of the fissile material—primarily 235U in this case. 238U can also fission, but has a fission threshold energy such that it can be considered inert.

- The mass of the fissile material.

- The degree of enrichment of the uranium.

- Moderation and reflection.

Neutrons produced during fission do not react well with other 235U nuclei; they must first be slowed down. This is done by interacting with light-element nuclei, such as hydrogen (e.g., in water). The presence of a moderator such as water is usually necessary for criticality. Water (or other light elements) surrounding the uranium can also slow down and reflect some of the neutrons back to the fissioning material. The presence of a moderator and a reflector will have a major effect on the "critical mass" capable of sustained reaction.

Loss of neutrons depends on the following factors:

- System geometry. A thin slab or a thin column has a large ratio of surface to mass and promotes the loss. A sphere has the minimum area per unit of mass and limits the loss. Some amounts that would be unsafe as a sphere could be handled safely as a thin slab.

- Neutron absorbers. Many materials react with neutrons; some are very effective at removing neutrons (e.g., boron, cadmium, and gadolinium). They are "neutron poisons."

The factors above can limit the extent and duration of a criticality accident through their effects on the system of the large energy release. In a liquid system, for example, there can be rapid boiling, and, as the moderating liquid evaporates, the system reverts to subcritical. However, the sudden large neutron release during the accident can still be lethal to anyone within a few feet of the scene.

Avoiding Criticality

The aqueous treatment for surface decontamination automatically introduces a moderator into the system, and criticality becomes a possibility. Methods for preventing criticality are based on the variables noted previously:

- Limiting the mass of 235U present.

- Controlling the degree of moderation, for example, limit the amount of hydrogenous material (under moderation) or limit the concentration of 235U in solution (overmoderation).

- Avoiding neutron reflection. Water next to a container can be a reflector, for example, in heat exchanger tubing. Concrete can also be a good reflector, as can people.

- Choosing appropriate geometry; for example, a thin layer of solution to maximize neutron loss.

- Using neutron absorbers. The preferred form of such absorbers is solid, such as borosilicate glass Raschig rings in the solution container. Soluble poisons may also be used, although there is concern about inadvertent separation from solution of such poisons (e.g., via precipitation) and selective separation of poisons in ion exchange resins.

- Some of the uranium will have a 235U enrichment level that is low enough that criticality is impossible under ordinary conditions of water moderation (235U less than 1.96 percent.)

An important concept in criticality safety is the "double-contingency principle:"

In recognition that improbable operational abnormalities cannot be ignored, the ANS-8.1 Standard delineates the double-contingency principle as a generally accepted guide to the proper degree of protection. The principle calls for controls that assure that no single mishap—regardless of its probability of occurrence—can lead to criticality. Stated another way, it requires that two unlikely, independent, and concurrent changes in process conditions occur before criticality is possible (Knief, 1991).

Critical limits for highly enriched uranium in solution are very restrictive (Table G-1). The values shown are "single-parameter" values for pure 235U solution, any one of which will ensure that the system will be subcritical.

Multiple-parameter controls provide significant relief from the extremely restrictive single-parameter limits of Table G-1. Control of solution concentration is one of the most useful ways to relax the single-parameter limits, but this immediately entails administrative control to ensure that the concentration is kept within specified limits. An example is shown in Table G-2, showing slab thicknesses and uranium concentrations (100 percent 235U) that will ensure subcritical conditions (Knief, 1991).

TABLE G-1 Single-Parameter Limits for Uniform Aqueous Solution of 235U

|

Parameter |

O2(NO3)2 |

UO2F2 |

|

Mass of uranium (kg) |

0.78 |

0.76 |

|

Solution cylinder diameter (cm) |

14.4 |

13.7 |

|

Solution slab thickness (cm) |

4.9 |

4.4 |

|

Solution volume (l) |

6.2 |

5.5 |

|

Concentration of uranium in solution (kg/l) |

0.0116 |

0.0116 |

|

Atomic ratio of H/U (lower limit) |

2,250 |

2,250 |

|

SOURCE: Clark (1982). |

||

TABLE G-2 Subcritical Limits for Aqueous Solution of 235UO2F2 with a Water Reflector (25 mm)

|

Slab Thickness (cm) |

Uranium Concentration (kg/l) |

|

8.6 |

1.0 |

|

8.0 |

0.5 |

|

9.8 |

0.1 |

|

13.0 |

0.05 |

|

31.0 |

0.015 |

|

SOURCE: ANS (1983). |

|

The data of Tables G-1 and G-2 apply to fully enriched uranium solutions only (not containing 238U). Lower enrichment reduces the criticality problem. Criticality is not possible in unmoderated uranium with less than 5 percent by weight 235U. Subcritical limits for various 235U enrichment levels are shown in Table G-3. Heterogeneous systems in water show somewhat lower criticality limits than homogeneous systems (Table G-4). For example, in mixtures of fine solid UO2 in water with excellent reflection and spherical geometry, criticality is possible at 235U concentrations of about 1 percent, but with very large critical masses (Knief, 1991).

TABLE G-3 Subcritical Limits for Uniform Aqueous Solutions of Low-Enriched Uranium for Different 235U Enrichment Levels

|

|

Parameter Subcritical Limit |

|

|

Parametera |

UO2F2 |

UO2(NO3)2 |

|

Mass 235U (kg) |

|

|

|

10.00% |

1.07 |

1.47 |

|

5.00% |

1.64 |

3.30 |

|

4.00% |

1.98 |

6.50 |

|

3.00% |

2.75 |

— |

|

2.00% |

8.00 |

— |

|

Cylinder diameter (cm) |

|

|

|

10.00% |

20.10 |

25.20 |

|

5.00% |

26.60 |

42.70 |

|

4.00% |

30.20 |

48.60 |

|

3.00% |

37.40 |

— |

|

2.00% |

63.00 |

— |

|

Slab thickness (cm) |

|

|

|

10.00% |

8.30 |

11.90 |

|

5.00% |

12.60 |

23.40 |

|

4.00% |

15.10 |

33.70 |

|

3.00% |

20.00 |

— |

|

2.00% |

36.00 |

— |

|

Volume (l) |

|

|

|

10.00% |

14.80 |

26.70 |

|

5.00% |

30.60 |

111.00 |

|

4.00% |

42.70 |

273.00 |

|

3.00% |

77.00 |

— |

|

2.00% |

340.00 |

— |

|

Uranium concentration (g/l) |

|

|

|

10.00% |

123.00 |

128.00 |

|

5.00% |

261.00 |

283.00 |

|

4.00% |

335.00 |

375.00 |

|

3.00% |

470.00 |

— |

|

2.88% |

— |

594.9b |

|

2.00% |

770.00 |

— |

|

1.45% |

1190.00b |

— |

|

a For different percentages of enrichment b Saturated solution SOURCE: ANS (1983). |

||

TABLE G-4 Critical Parameters for Solid UO2 Dispersal in Water with 300-mm-Thick Water Reflector

|

Wt % 235U |

Spherical Massa (kg U) |

Cylinder Diameter (cm) |

Slab Thickness (cm) |

Volume (l) |

|

1 |

1,900 |

70 |

42 |

500 |

|

2 |

165 |

34 |

18 |

60 |

|

3 |

76 |

28 |

12 |

32 |

|

4 |

44 |

24 |

11 |

25 |

|

5 |

27 |

22 |

10 |

20 |

|

a Mass shown is mass of total uranium SOURCE: Knief (1991). |

||||

Factors of safety will always be applied to ensure that the critical limits are not reached in operating cleanup equipment. For example, one report (MMES, 1988) considers 350 grams of 235U as "always safe" for any enrichment of 235U. Nuclear Regulatory Commission licensing of the special nuclear material burial site in Washington State allows a maximum of 500 grams (a critically safe quantity) of 235U per container and a maximum of 15 g/ft3. These mass quantities are significantly less than the subcritical limits shown in Table G-1, for example; they have been chosen to provide a factor of safety.

Deposits within diffusion plant converters raise concerns about nuclear criticality. The concerns depend, however, on enrichment level and amount of 235U in the deposits, which covers a very wide range:

- The low enrichment section of all of these plants (those providing enrichment levels of less than 1.4 percent 235U, for example) will contain deposits of less than critical mass.

- The Oak Ridge plant has some very large deposits that must be considered critically unsafe and will require great care.

- The enrichment level at Paducah is low enough (2 percent, with an increase to 2.75 percent in 1995) that critical size deposits are very unlikely. The Portsmouth plant is being treated with gaseous chlorine trifluoride to reduce the 235U content of individual converters to less than 350 grams, a critically safe level.

Criticality will be a concern at all three plant sites where aqueous treatment is used and where the 235U concentration could build up in solution. Eliminating the criticality concern at individual converters could certainly reduce D&D costs (Lacy, 1994).

Summary

Aqueous washing of enriched uranium (e.g., over 2 percent enriched 235U) from metal parts requires criticality controls: restricting 235U amount and geometry (e.g., to occur only in thin layers), and possibly using neutron poisons. Double-contingency planning is needed. One way to reduce this is to do the work remotely, behind barriers.

It is particularly useful to remove enriched material as thoroughly as possible before water is introduced into the system. Dry cleanup (e.g., scraping or vacuuming) minimizes the subsequent criticality problem in the water-moderated system.

The criticality problem is greatly reduced at low 235U enrichment. The cleanup system can be simplified in such cases, with cost reduction.

References

ANS (American Nuclear Society). 1983. Nuclear Criticality Safety in Operations with Fissionable Materials Outside Reactors. ANSI/ANS-8.1/N-16.1-1975. La Grange, Illinois: American Nuclear Society.

Knief, R. 1991. Nuclear Criticality and Safety, Theory and Practice. La Grange, Illinois: American Nuclear Society.

Clark, H. 1982. Supercritical limits for uranium-235 systems. Nuclear Science and Engineering 81(3) 351–78.

Lacy, N. 1994. Gaseous Diffusion Plants Decontamination and Decommissioning Assessment Review Issue Papers (predecisional draft). Washington, D.C.: Booz-Allen/Burns and Roe for the U.S. Department of Energy. January 14.

MMES (Martin Marietta Energy Systems). 1988. Nuclear Criticality Safety Guide for the Portsmouth Gaseous Diffusion Plant. GAT-225, rev 4. Piketon, Ohio: MMES.