The Waste Isolation Pilot Plant: A Potential Solution for the Disposal of Transuranic Waste (1996)

Chapter: D. CREEP BEHAVIOR OF WIPP SALT

Appendix D Creep Behavior of WIPP Salt

One of the main attributes of salt as a rock formation in which to isolate radioactive waste is the ability of the salt to creep, that is, to deform continuously over time. Excavations into which the waste-filled drums are placed will close the salt eventually, flowing around the drums and sealing them within the formation. A good understanding of the rate of closure and associated phenomena, such as the development and healing of fractures around the excavations, is essential for the design of an effective repository in salt.

The program of investigations into the mechanics of deformation of salt at the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant (WIPP) has been more extensive and comprehensive than any previous studies world-wide. Carried out over the past decade and a half, it has included theoretical studies coupled with small-scale laboratory tests and full-scale field investigations underground at WIPP.

Initial predictions of the rate of closure of underground excavations—based on deformation parameters derived from laboratory tests—were found to be some three to six times lower than the closure rates observed underground. Continued research to improve fundamental understanding has resulted in a very substantial reduction in this discrepancy. Thus, for the majority of the in situ cases studied, agreement between the closure rates predicted from small-scale laboratory test data and those actually observed is now within approximately 10 percent. Larger discrepancies can be attributed, in some cases, to exclusion of the following from the three-dimensional numerical codes used for the predictions:

- discrete slip surfaces (e.g., between the salt and anhydrite interbeds) in the vicinity of the excavations, and

- separation of interbeds and salt layers in the roof of the excavations.

These limitations are not serious for the assessment of closure performance of the excavations at WIPP since, in both cases, actual closure will somewhat exceed the predicted value. Thus, predictions will be conservative.

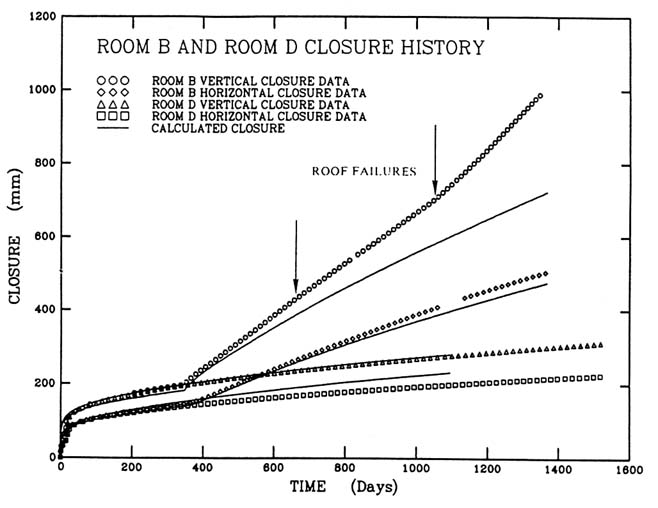

Although salt deformation appears to involve a complex interaction of a multiplicity of microscopic mechanisms, these combine to produce a relatively simple, essentially constant rate of room closure (Figures D.1 and D.2).

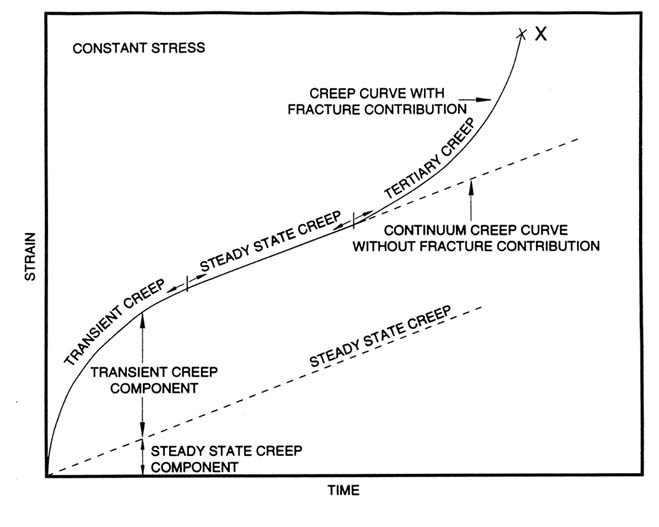

As shown in Figure D.3, the strain-time behavior of salt can be considered to consist of several regions, namely, εE, an elastic strain, which appears immediately upon loading (the amount of elastic strain increases with increase in the applied stress); this is followed by

- a region of primary or transient creep strain;

- a region of secondary or "steady-state creep" (where the strain rate εp is essentially constant); and

- a region of tertiary or "accelerating creep" strain.

Accelerating strain indicates a progressive disintegration of the salt structure, leading eventually to collapse.

It is well known that the strain rates involved in salt creep increase in a highly nonlinear manner with increases in temperature and applied stress.

An extensive series of laboratory investigations has led to the definition of a new constitutive model (i.e., relationship between steady-state creep rate and applied load) for WIPP salt. This model is known as the modified Munson-Dawson or multimechanism deformation (M-D) constitutive model.

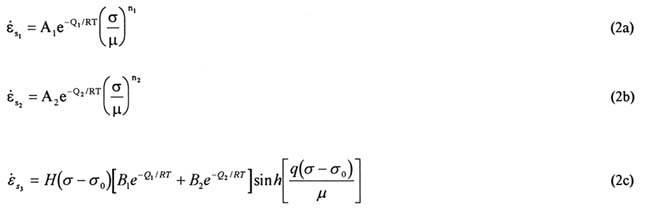

In the M-D model, the total steady-state creep rate (εs) is considered to be the sum of three component rates, each dependent on a different fundamental mechanism to creep in the salt: Thus

where the individual steady-state rates of the three relevant mechanisms are given by

where A and B are constants; Q is the activation energy; T is the absolute temperature; R is the universal gas constant; μ is the shear modulus; σ is the generalized stress; n is the stress exponent; g is the stress constant; σ0 is the lower stress limit of the dislocation slip mechanism; and H is the Heaviside step function with argument σ - σ0 [i.e., H(σ - σ0)= 0 for σ < σ0; 1 for σ > σ0].

A complete list of the values of the various constants in Equations (2a - c) for WIPP salt is presented in Munson (1996). For the current discussion, it is sufficient to note the following:

- WIPP underground excavations will not be subject to any significant temperature changes (except for remote—handled transuranic waste locations, where some moderate temperature increases may occur). Thus, temperature dependence on creep closure need not be considered to a first approximation.

- The value of σ0 has been determined to be 20.57 MPa (megaPascals). For most of the underground locations at WIPP, since the initial stress state is isotropic (lithostatic pressure in every direction) at approximately 15 MPa, then H(σ - σ0) = 0, implying that εs = 0 for these locations.

- Using the values n1 = 5.5 and n2 = 5.0 for the exponents in Equations (2a) and (2b), the steady-state strain rate εs reduces to the expression

where the generalized stress σ = (σ1 - σ3); σ1 and σ3 are the maximum and minimum principal stresses, respectively; and k1 and k2 are constants representing combinations of terms in Equations (2a) and (2b), respectively.

For simplicity, it is assumed that both components of Equation (3) have the same exponent (i.e., assuming n2 ≈ n1 = 5.5), so Equation (3) can be written as

where k = k1 + k2. It is seen that the stress dependence of the creep rate is very strong. For example, if an open borehole in salt closes at the steady-state rate (εp)open at some depth h (meters) (i.e., where the lithostatic [driving] stress is 0.023h MPa), then a brine-filled borehole (with a hydrostatic pressure

in the hole of 0.01h MPa) will close at a rate (·εp)fluid-filled, where

Thus, if an open unlined borehole closes in approximately 100-200 years, an unlined, fluid-filled borehole at the same depth would not close for 3,700-7,400 years. This is a significant change when estimating the consequences of human intrusion events.

Research at WIPP has also confirmed the following:

- The stress at which inelastic flow of salt occurs is governed by a Tresca or maximum shear stress yield criterion, rather than the more frequently used Von Mises, or maximum octahedral shear stress yield criterion. Given the highly non-linear dependence of the strain and strain rate on stress level, the difference between the two criteria can be very significant. A part of the initial discrepancy between prediction and observation was corrected by making the change to a Tresca criterion.

- The value of the shear stress at which inelastic strain develops tends toward very low levels at low strain rates. At the very low strain rates associated with geological loading, the yield stress of salt is essentially zero. In other words, at these extremely low loading rates, salt behaves as a (viscous) fluid, unable to maintain a shear stress. This is seen in equation (4) above, which indicates that the salt will have a nonzero strain rate (εs) as long as σ1 ≠ σ3. Thus, over long times (especially geological time—here 200 million years) creep will continue until σ1 = σ3, (i.e. the in-situ stress state is isotropic).

Hydraulic fracturing measurements of in situ stress conditions of WIPP confirm that the stress state in the salt is isotropic. The isotropic condition and the creep flow characteristic of salt imply that salt in situ should be essentially impermeable, since the connected pathways needed to allow flow of fluid would lead to localized stress concentrations in the vicinity of the connected cracks, etc., that represent the permeability. Such concentrations (stress differences) would produce flow of the salt, leading to closing of the pathway and elimination of the permeability.

- At the higher strain rates associated with stress redistribution around excavations, salt can behave in a much more brittle manner. Fractures can and do develop progressively in the walls, roof, and floor of the excavation as the result of stress concentrations around the excavations. These fractures produce what is known as the disturbed rock zone (DRZ) around the excavations. The DRZ is important on several counts:

-

- It could provide a region of connected fractures that allow a high-permeability path around the excavations and brine access to the waste-filled drums. Such fractures (and DRZs) appear around excavations in other rock types, but salt has the attractive feature that fractures in the DRZ in salt can "heal" (i.e., disappear) with the buildup of a "back-stress" (i.e., resistance to closure generated by waste and/or backfill or a shaft lining or seal). This healing can be inhibited by the presence of water in the fractures as back-stress builds up. In the shaft seal designs discussed in Chapter 4, the DOE must take special measures to ensure that the fractures remain "drained" during the period of back-stress buildup. It is worth noting, however, that the fluid pressure required to resist crack closure can develop only if the fluid is sealed in the crack, that is, if it is not part of a permeable connected system of fluid flow.

- Since the DRZ develops in the floor of the excavations as well as the roof and sides, this zone serves as a depository and conduit for any brine flowing into the waste-filled rooms. Because closure of the waste-filled rooms involves floor "heave" as well as roof "sag," the waste drums will tend to be lifted above the brine, especially during the early years after loading of the rooms with waste. This phenomenon has important implications for the question of gas generation due to corrosion of steel waste drums at WIPP.

-

The practical implications of these deformation properties of salt are discussed in Chapters 3 and 4.