Flight to the Future: Human Factors in Air Traffic Control (1997)

Chapter: 12 AUTOMATION

12

Automation

Automation technology for air traffic control has steadily advanced in complexity and sophistication overtime. Techniques for measurement and control, failure detection and diagnosis, display technology, weather prediction, data and voice communication, multitrajectory optimization, and expert systems have all steadily improved. These technological advances have made realistic the prospect of revolutionary changes in the quality of data and the aids available to the air traffic controller. The most ambitious of this new generation of automated tools will assist and could replace the controller's decision-making and planning activities.

Although these technological developments have been impressive, there is also little doubt that automation is far from being able to do the whole job of air traffic control, especially to detect when the system itself is failing and what to do in the case of such failure. The technologies themselves are limited in their capabilities, in part because the underlying models of the decision-making processes are oversimplified. As we have noted, it is unlikely that technical components of any complex system can be developed in such a way as to ensure that the system, including both hardware and software components, will never fail. The human is seen as an important element in the system for this reason to monitor the automation, to act as supervisory controller over the subordinate subsystems, and to be able to step in when the automation fails. Humans are thought to be more flexible, adaptable, and creative than automation and thus better able to respond to changing or unpredictable circumstances. Given that no automation technology (or its human designer) can foresee all possibilities in a complex environment,

the human operator's experience and judgment will be needed to cope with such conditions.

The implementation of automation in complex human-machine systems can follow a number of design philosophies. One that has received considerable recent interest in the human factors community is the concept of human-centered automation. As we mentioned earlier in this report, human-centered automation is defined as "automation designed to work cooperatively with human operators in pursuit of stated objectives" (Billings, 1991:7). This design approach is discussed in more detail toward the end of this chapter.

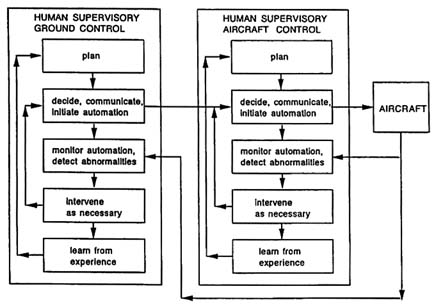

Over a decade of human-factors research on cockpit automation has shown that automation can have subtle and sometimes unanticipated effects on human performance (Wiener, 1988). In a recent report (Federal Aviation Administration, 1996a) the impact of cockpit automation on flight deck crew performance has been documented in some detail. Similar effects have been noted in other domains in which advanced automation has been introduced, including medical systems, ground transportation, process control, and maritime systems (Parasuraman and Mouloua, 1996). Understanding these effects is important for ensuring the successful implementation of new forms of automation, although not all such influences of automation on human performance will apply to the air traffic control environment. The nature of the relationships between controllers and ground control systems on one hand, and pilots and aircraft systems on the other, will also change in as yet unknown ways. For example, at one extreme, control of the flight path and maintenance of separation could be achieved by automated systems on the ground, data-linked to flight deck computers. At the other extreme, as in some of the concepts involved in free flight, all responsibility for maintaining separation could rest with the pilot and on-board traffic display and collision avoidance systems (Planzer, 1995). Whether or not the most advanced automated tools are implemented, however, it is likely that the nature of the controller's tasks will change dramatically. At the same time, future air traffic control will require much greater levels of communication and integration between ground and airborne resources.

In this chapter, we focus on four aspects of automation in air traffic control. We first describe the different forms and levels of automation that can be implemented in human-machine systems in general. Second, we describe the functional characteristics of several examples of air traffic control automation, covering past, current, and new systems slated for implementation in the immediate future. We do not discuss automation concepts that are still in the research and development stage, such as free flight, or the national route program, which will provide indications of air traffic control capabilities and requirements relevant for free flight considerations. Third, we discuss a variety of important human factors issues related to automation in general, with a view to drawing implications for air traffic control (see also Hopkin, 1995). Recent empirical investigations and human factors analyses of automation have been predicated on the view

that general principles of human operator interaction with automation apply across domains of application (Mouloua and Parasuraman, 1994; Parasuraman and Mouloua, 1996). Thus, many of the ways in which automation changes the nature of human work patterns may apply to air traffic control as well. At the same time, there may also be some characteristics of human interaction with automation that are specific to air traffic control. This caveat should be kept in mind because most of what has been learned in this area has come from studies of cockpit automation and, to a lesser extent, automation in manufacturing and process control. Finally, we discuss the attributes of human-centered automation as they apply to air traffic control.

FORMS OF AUTOMATION

The term automation has been so widely used as to have taken on a variety of meanings. Several authors have discussed the concept of automation and tried to define its essence (Billings, 1991, 1996; Edwards, 1977; Sheridan, 1980, 1992, 1996; Wiener and Curry, 1980). The American Heritage Dictionary (1976) definition is quite general and therefore not very illuminating: "automatic operation or control of a process, equipment, or a system." Other definitions of automation as applied to human-machine systems are quite diverse, ranging from, at one extreme, a tendency to consider any technology addition as automation, and, at the other extreme, to include only devices incorporating "intelligent" expert systems with some autonomous decision-making capability as automation.

Definition

A middle ground between the two extreme views of automation would be to define automation as: a device or system that accomplishes (partially or fully) a function that was previously carried out (partially or fully) by a human operator.

Because this definition emphasizes a change in the control of a function from a human to a machine (as opposed to the machine control of a function never before carried out by humans), what is considered automation will change overtime with technological development and with human usage. Once a function is allocated to a machine in totality, then after a period of time the function will tend to be seen simply as a machine operation, not as automation. The reallocation of function is permanent. According to this reasoning, the electric starter motor of an automobile, which serves the function of turning over the engine, is no longer considered automation, although in the era when this function was carried out manually with a crank (or when both options existed), it would have been so characterized. Other examples of devices that do not meet this definition of automation are the automatic elevator and the fly-by-wire flight controls on many modern aircraft. By the same token, cruise controls in automobiles and autopilots in aircraft represent current automation. In air traffic control, electronic flight

strips represent a first step toward automation, whereas such decision-aiding automation as the final approach spacing tool (FAST)(Erzberger, 1992) represents higher levels of automation that could be implemented in the future. Similar examples can be found in other systems in aviation, process control, manufacturing, and other domains.

From a control engineering perspective, automation can be categorized into (and historically automation has progressed through) several forms:

-

Open-loop mechanical or electronic control. This was the only automation at first, as epitomized by the elegant water pumping and clockworks of the Middle Ages: gravity or spring motors driving gears and cams to perform continuous or repetitive tasks. Positioning, forcing, and timing were dictated by the mechanism and whatever environmental disturbances (friction, wind, etc.) that happened to be present. The automation of factories in the early parts of the Industrial Revolution was also of this form. In this form of automation, there is no self-correction by the task variables themselves. Much automation remains open loop, and precision mechanical parts or electronic timing circuits ensure sufficient constancy.

-

Classic linear feedback control. In this form of automation, the difference between a reference setting of the desired output and a measurement of the actual output is used to drive the system into conformance. The flyball governor on the steam engine was probably the first such device. The gun-aiming servo-mechanisms of World War II enlarged the scope of such automation tremendously. What engineers call conventional proportional-integral-derivative (PID) control also falls into this category.

-

Optimal control. In this type of control, a computer-based model of the controlled process is driven by the same control input as that used to control the actual process. The model output is used to predict system state and thence to determine the next control input. The measured discrepancy between model and actual output is then used to refine the model. This "Kalman filtering" approach to estimating (observing) the system state determines the best control input, under conditions of noisy state measurement and time delay, "best" being defined in terms of a specified trade-off between control error, resources used, and other key variables. Such control is inherently more complex than PID control but, when computer resources are available, it has been widely adopted.

-

Adaptive control. This is catchall term for a variety of techniques in which the structure of the controller is changed depending on circumstances. This category includes the use of rule-based controllers (either "crisp" or "fuzzy" rules or some combination), neural nets, and many other nonlinear methods.

Levels of Automation

It is useful to think of automation as a continuum rather than as an all-or-nothing

TABLE 12.1 Levels of Automation

|

1. |

The computer offers no assistance, the human must do it all. |

|

2. |

The computer offers a complete set of action alternatives, and |

|

3. |

narrows the selection down to a few, or |

|

4. |

suggests one, and |

|

5. |

executes that suggestion if the human approves, or |

|

6. |

allows the human a restricted time to veto before automatic execution,or |

|

7. |

executes automatically, then necessarily informs the human, or |

|

8. |

informs the human after execution only if he asks, or |

|

9. |

informs the human after execution if it, the computer, decides to. |

|

10. |

The computer decides everything and acts autonomously, ignoring the human. |

|

Source: Sheridan (1987). |

|

concept. The notion of levels of automation has been discussed by a number of authors (Billings, 1991, 1996; Hopkin, 1995; McDaniel, 1988; National Research Council, 1982; Parasuraman et al., 1990; Sheridan, 1980; Wickens, 1992). At the extreme of total manual control, a particular function is continuously controlled by the human operator, with no machine control. At the other extreme of total automation, all aspects of the function (including its monitoring) are delegated to a machine, so that only the end product and not its operation is made available to the human operator. In between these two extremes lie different degrees of participation in the function by the human and by automation (Table 12.1). At the seventh level, for example, the automation carries out a function and is programmed to inform the operator to that effect, but the operator cannot influence the decision. McDaniel (1988) similarly described the level of monitored automation as one at which the automation carries out a series of operations autonomously that the human operator is able to monitor but cannot change or override. Despite the relatively high level of automation autonomy, the human operator may still monitor the automation because of implications elsewhere for the system, should the automation change its state.

What is the appropriate level of automation? There is no easy or single answer to this question. Choosing the appropriate level of automation can be relatively straightforward in some cases. For example, most people would probably prefer to have an alarm clock or a washing machine operate at a fairly high level of automation (level 7 or higher), and a baby-sitting robot set at a fairly low level of automation, or not at all (level 2 or 1). In most complex systems, however, the choice of level of automation may not be so simple. Furthermore, the level of automation may not be fixed but context dependent; for example, in dynamic systems such as aircraft, the pilot will select whatever level he or she considers appropriate for the circumstances of the maneuver.

The concept of levels of automation is also useful in understanding distinctions in terminology with respect to automation. Some authors prefer to use the term automation to refer to functions that do not require, and often do not permit,

any direct participation or intervention in them by the human operator; they use the term computer assistance to refer to cases in which such human involvement is possible (Hopkin, 1995). According to this definition of automation, only technical or maintenance staff could intervene in the automated process. The human operator who applies the products of automation has no influence over the processes that lead to those products. For example, most previous applications of automation to air traffic control have affected simple, routine, continuous functions such as data gathering and storage, data compilation and correlation, data synthesis, and the retrieval and updating of information. These applications are universal and unselective. When some selectivity or adaptability in response to individual needs has been achieved or some controller intervention is permitted, automation then becomes computer assistance.

Because the notion of multiple levels of automation includes both the concepts of automation and computer assistance, only the term automation is used in the remainder of this chapter. However, our use of this term does not imply, at this stage in our analysis, adoption of a general position on the appropriate level for the air traffic control system, whether full automation or computer assistance.

Authority and Autonomy

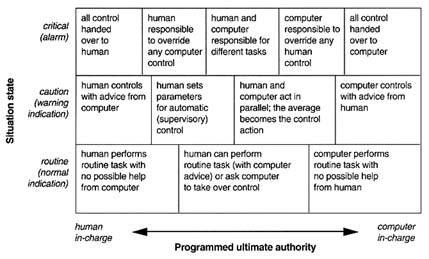

Higher levels of automation are associated with greater machine autonomy, with a corresponding decrease in the human operator's ability to control or influence the automation. The level of authority may also be characterized by the degree of emergency or risk involved. Figure 12.1 shows a two-dimensional characterization of where authority might reside (human versus computer) in this respect.

Sarter and Woods (1994a, 1995a, 1995b) have suggested that automation, particularly high-level automation of the type found in advanced cockpits, needs to be decomposed with respect to critical properties such as autonomy, authority, and observability. Although these terms can be defined in many instances, there are cases in which they are independent of one another and cases in which they are not. Autonomous automation, once engaged, carries out many operations with only early initiating input from the operator. The operations respond to inputs other than those provided by the operator (from sensors, other computer systems, etc.). As a result, autonomous automation may also be less "observable" than other forms of automation, though machine functions can be programmed to keep the human informed of machine activities. Automation authority refers to the power to carry out functions that cannot be overridden by the human operator. For example, the flight envelope protection function of the Airbus 320 cannot be overridden except by turning off certain flight control computers. The envelope protection systems in other aircraft (e.g., MD-11 and B-777), however, have "soft" limits that can be overridden by the flight crew.

FIGURE 12.1 Alternatives for ultimate authority as related to risk.

Autonomy and authority are also interdependent automation properties (Sarter and Woods, 1994a).

Sarter and Woods (1995b) propose that the combination of these properties of high-level automation creates multiple ''agents" in the workplace who must work together for effective system performance. Although the electronic copilot or pilot's associate (Chambers and Nagel, 1985; Rouse et al., 1990) is still a future concept for the cockpit, current cockpit automation possesses many qualities consistent with autonomous, agent-like behavior. Unfortunately, because the properties of the automation can create strong but silent partners to the human operator, mutual understanding between machine and human agents can be compromised (Sarter and Woods, 1995b). Future air traffic management systems may incorporate multiple versions of such agents, both human and machine, and both on the ground and in the air.

FUNCTIONAL CHARACTERISTICS

Despite the high-tech scenarios that are being contemplated for the 21st century (e.g., free flight), current air traffic control systems, while including some automation (e.g., automated handoffs, conflict warnings), remain largely manual. The influence on air traffic control operations of existing and proposed automation, both near-term and long-term, has been discussed extensively in recent years as the prospects for implementing various forms of advanced automation have become clear (Harwood, 1993; Hopkin, 1991, 1994, 1995; Hopkin and Wise, 1996; Vortac, 1993). In this section we describe the functional characteristics

of air traffic control automation, emphasizing currently implemented technologies or immediate near-term proposals for automation, rather than "blue-sky" concepts. Before describing specific examples, however, we discuss the rationale for implementing automation, both generally and as represented in the strategic planning of the FAA.

The Need for Automation

More people wish to use air transportation, and more planes are needed to get them to their destinations. All current forecasts foresee substantial future increases in air traffic and a continuing mix of aircraft types. The FAA must face and accommodate increasing demands for air traffic control services. Current systems were never intended to handle the quantities of air traffic now envisaged for the future. Many of them are already functioning at or near their planned maximum capacity for traffic handling much of the time. Present practices, procedures, and equipment are often not capable of adaptation to cope with a lot more traffic. In addition, traffic patterns, predictability, and laws of control may change. New systems therefore have to be designed not merely to function differently initially but also to evolve differently while they are in service. The apparent option of leaving air traffic control systems unchanged and expecting them to cope with the predicted large increases in traffic is therefore not a practical option at all. Air traffic control must change and evolve (Wise et al., 1991) to meet the foreseen changes in demand.

The limited available airspace in regions of high traffic density constrains the kinds of solutions to the problem of increased air traffic. The only way to handle still more air traffic within regions that are already congested is to permit each aircraft to occupy less airspace. This means that aircraft will be closer together. Their safety must not be compromised in any way, they must not be subjected to more delays, and each flight should be efficient in its timing, costs, and use of resources. To further these objectives, flight plans, navigational data, on-board sensors, prediction aids, and computations can provide information about the state of each flight, the flight objectives, its progress, and its relationships to other flights, and about any potential hazards such as adverse weather, terrain proximity, and airspace restrictions or boundaries. All this information, combined with high-quality information about the position of each aircraft on its route and about the route itself, could allow the minimum separation standards between aircraft to be reduced safely.

Since changes in air traffic control tend to be evolutionary rather than revolutionary, current systems have to be designed so that they can evolve to integrate and make effective use of such developments in technology during the lifetime of the system. The appearance and functionality of some current systems have therefore been influenced, sometimes considerably, by the ways in which they are expected to be improved during their operational lifetime. Common current

examples are the replacement of paper flight progress strips by electronic ones and the advent of data links. Many of the remaining practical limitations on the availability of data for air traffic control purposes are expected eventually to disappear altogether.

One apparent response to the problem of increased air traffic can be ruled out: that is simply to recruit more controllers and to make each controller or each small team of controllers responsible for the air traffic in a smaller region of airspace. Unfortunately, in many of the most congested airspace regions, this process has already been taken about as far as is practicable, because the smaller the region of airspace of each air traffic control sector, the greater the amount of communication, coordination, liaison, and handoff required in the air traffic control system itself and in the cockpit, whenever an aircraft flies out of one controller's jurisdiction and into another's. Eventually any gains from having smaller regions are more than canceled by the associated additional activities incurred by the further partitioning of the airspace.

Automation has therefore been seen by some as the best alternative to the problem of increased traffic demand. Automation may include technologies for such functions as information display, communication, decision making, and cooperative problem solving. Free flight is an alternate remedy that has been recently proposed (RTCA, 1995; Planzer and Jenny, 1995). However, increased traffic is only one factor in the drive to automate the air traffic control system. Another factor is the increasing tendency of air traffic control providers to serve rather than to control the aviation community in its use of airspace resources. Automation is seen as one of the ways in which service providers can meet the needs of airspace customers, both now and in the future (Federal Aviation Administration, 1995).

The advanced automation system (AAS) was a major program of technology enhancement that was initiated by the FAA in the 1980s. Despite its title, the program was largely concerned with the modernization of equipment and, although some parts of the program did deal with automation, the major thrust was not with automation per se. In 1994, following delays and other problems in meeting the goals of the program, the AAS was divided into smaller projects, each concerned with replacement of aging equipment with newer, more efficient, and powerful capabilities. In contrast to these efforts at improving the air traffic control infrastructure, other planning efforts have focused more specifically on automation. The FAA's plans for automation are contained in its Automation Strategic Plan (Federal Aviation Administration, 1994) and the Aviation System Capital Investment Plan (Federal Aviation Administration, 1996b). Two major goals for automation are identified: the improvement of system safety and an increase in system efficiency. In the context of safety automation is proposed because of its potential to:

-

Reduce human error through better human-computer interfaces and improved data communications (e.g., datalink),

-

Improve surveillance (radar and satellite-based),

-

Improve weather data,

-

Improve reliability of equipment, and

-

Prevent system overload.

Automation is proposed to improve system efficiency because of its potential to:

-

Reduce delays,

-

Accommodate user-preferred trajectories,

-

Provide fuel-efficient profiles,

-

Minimize maintenance costs, and

-

Improve workforce efficiency.

Air Traffic Control Automation Systems: General Characteristics

There is no easy way to classify or to even list comprehensively all of the various automation systems that have been deployed in air traffic control. In this section, we describe the major systems that have been fielded in the United States and discuss the principal functional characteristics of the automation to date, making reference to specific systems as far as possible. Although there is considerable diversity in the technical features, functionality, and operational experience with different automation systems, some generalizations are possible.

-

On the whole, automation to date has been successful,1 in the sense that the new technologies that have been fielded over the past 30 years have been fairly well integrated into the existing air traffic control system and have generally been found useful by controllers. This is clearly a positive feature, and efforts should be made to ensure its continuity in the future as new systems are introduced.

-

There has been a steady increase in the complexity and scope of automated systems that have been introduced into the air traffic control environment. In terms of functionality, automation to date has largely been concerned with improving the quality of the information provided to the controller (e.g., automated data synthesis and information presentation) and with freeing the controller from simple but necessary routine activities (e.g., automated handoffs to other sectors) and less so with the automation of decision-making and planning functions. Historically, following the development of automation of data processing,

-

Automation systems that are currently under field testing or about to be deployed in the near future (e.g., the center-TRACON automation system—CTAS), will have a greater impact on the controller's complex cognitive activities, the role of which was discussed extensively in Chapter 5. Higher levels of automation, with possibly greater authority and autonomy, may be the next to follow. Some of these systems are briefly mentioned in this chapter, but a more detailed discussion is expected in Phase 2 of the panel's work.

-

Although processing of flight data and radar data automatically distributes common data to team members, and although automated handoff supports pairs of controllers, automation to date, as well as most future projected systems, has been designed to support individual controllers rather than teams of controllers. Given the importance of team activities to system performance (discussed in Chapter 7), this fact will need to be taken into account in evaluating the impact of future automation.

-

Different forces have led to the development and deployment of air traffic control automation systems. In some cases, technology has become available, or there has been technology transfer from other domains, as in the case of the global positioning system (GPS). Other contributing sources to the development of particular automation systems include controllers, users of air traffic control services, the FAA, and human factors research efforts.

-

Finally, cockpit automation has generally been more pervasive than air traffic control automation. Some of these systems, such as the FMS and TCAS, have implications for air traffic control and hence must be considered in any discussion of air traffic control automation.

Table 12.2 provides an overview of the automated systems that have been implemented in the air traffic control environment. Automation technologies introduced overtime are represented along the columns, with the rows representing the four major types of environments. The distinction among tower, TRACON, en route, and oceanic air traffic control is just one of many ways in which the system could be subdivided, but it is convenient for the purpose of identifying specific systems that have been implemented, from the initial automation of data-gathering functions to the more advanced decision-aiding technologies that are currently under production. Because some cockpit automation systems (such as TCAS) have significant implications for control of the airspace, relevant cockpit systems are also shown in the table.

TABLE 12.2 Introduction of Automation Systems in Air Traffic Control, 1960s–1990s

|

ENVIRONMENT |

AUTOMATION SYSTEMS |

|||||||

|

|

1960s |

1970s |

|

1980s |

|

1990s |

|

|

|

Tower |

|

ASDE |

RVR |

|

LLWAS |

AMASS |

TDWR |

|

|

|

HABTCC |

|||||||

|

Terminal |

ARTS |

|

|

CA |

|

CTAS |

CTAS (FAST) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

MSAW |

|

(DA/TMA) |

VSCS |

|

|

En Route |

RDP |

FDP |

|

CA |

HOST |

ERM |

CTAS |

|

|

|

|

|

|

MSAW |

|

|

(DA/TMA) |

|

|

Oceanic |

|

|

|

|

ODAPS |

|

OSDS |

|

|

Cockpit Systems with air traffic control implications |

|

|

|

GPWS |

FMS |

TCAS |

GPS |

|

|

|

|

|

|

GPS |

Global Positioning System |

|||

|

AMASS |

Airport Movement Area Safety System |

GPWS |

Ground Proximity Warning System |

|||||

|

ARTS |

Automated Radar Terminal System |

HOST |

Host Computer Upgrade |

|||||

|

ASDE |

Airport Surface Detection Equipment |

LLWAS |

Low Level Windshear Advisory System |

|||||

|

HABTCCC |

High Availability Basic Tower Control Computer Complex |

MSAW |

Minimum Safe Altitude Warning |

|||||

|

CA |

Conflict Alert |

ODAPS |

Oceanic Display and Planning System |

|||||

|

CTAS |

Center-TRACON Automation System |

OSDS |

Oceanic System Development and Support |

|||||

|

DA |

Descent Advisor |

RDP |

Radar Data Processing |

|||||

|

ERM |

En-Route Metering System |

RVR |

Runway Visual Range System |

|||||

|

FAST |

Final Approach Spacing Tool |

TCAS |

Traffic Alert Collision Avoidance System |

|||||

|

FDP |

Flight Data Processing |

TDWR |

Terminal Doppler Weather Radar |

|||||

|

FMS |

Flight Management System |

TMA |

Traffic Management Advisor |

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

VSCS |

Voice Switching Control System |

|||

Flight Data Gathering and Processing

Data Gathering

Originally the gathering of data about forthcoming and current flights was entirely a human activity, prior to the introduction of the radar data processing system to the en route environment. The controller or an assistant wrote on a strip of paper, called a flight progress strip, all the essential information about a forthcoming flight, amending and updating it by hand as further information was gathered about the progress of the flight and as instructions were issued by the controller and agreed to by the pilot. When the responsibility for a flight passed to another controller, either its flight strip was physically handed over or parallel strips were prepared in advance and marked appropriately when responsibility was transferred. Flight strips plus speech communication channels between the controller and pilots were the basic procedural tools of air traffic control—and they still are. They are found wherever a minimally equipped air traffic control service is provided, which is often in regions with low levels of air traffic, in regions in which minimally equipped aircraft are the main traffic, and at locations in which the air traffic control service is not provided on a permanent basis. Controllers still rely on these nonautomated tools wherever there is no radar, either because the flight is beyond radar coverage, which is a common event and applies to much oceanic air traffic control, or because the radar has failed, which is a rare event.

The automation of data gathering has progressed so far that the controller may now spend very little time gathering data. The data are now presented automatically in forms that satisfy the task requirements, with appropriate data formats and levels of detail and with appropriate timing so that some data are not presented all the time but only when they are needed. Behind this revolution for the controller are many technical advances in the sensing, processing, storage, compilation, and synthesis of data. Much time formerly spent by the controller in gathering data is saved.

Data Storage

A significant area of automation is data storage, beginning with the automated radar terminal system (ARTS) for terminals and the flight data processing (FDP) for en route centers (see Table 12.2). The automation of data storage, associated with the widespread use of computers, seems so obvious that it is taken for granted, but it has a big effect on the controller. Originally the paper flight progress strips were the data storage, and there was no other. It is still quite common for the paper flight progress strip to constitute the official record of a flight for purposes such as the levying of charges for air traffic control services (in Europe) and subsequent incident investigation. Now a great deal of information

is stored about each flight and applied for data synthesis, for data presentation, and for computations. The controller relies on this data storage and makes extensive use of it, albeit often indirectly through the aspects of it represented on visual displays or aurally. This stored database has to be matched with the controller's tasks. Sometimes the controller has extra tasks because of it. For example, the written amendment of a paper flight progress strip to record a control action agreed to by a pilot is not sufficient to enter that agreement into the database of the system, and the change may have to be keyed in as well in order to enter it into the computer and store it automatically. This has prompted a quest for forms of automation that could avoid such duplication of functions, so that the same executive controller action both informs the pilot and updates the data storage.

Data Smoothing

Automation is widely applied to smooth data for human use. The original unprocessed data, very frequently sampled, contain numerous generally small anomalies concerning the aircraft's position, altitude, speed, heading, and other quantitative flight parameters. These are too small to be relevant to air traffic control but not too small to be distracting. They are removed by smoothing so that aircraft appear to turn, climb, descend, accelerate, and decelerate consistently along flight paths depicted as smoothed. In earlier times, aircraft were seen to perform more raggedly and with more vacillations, as an artifact of sensing methods, sampling rates, and anomalies in the processing and depiction of information, and the controller had to do data smoothing by extrapolation. This is now done automatically, striking a balance so that genuine and operationally significant aberrations are not smoothed away.

Data Compilation and Synthesis

Not only are the sensed data summarized and smoothed automatically, but sometimes they are also combined, represented in different forms, or otherwise transformed to make them suitable for human use. Such functions are automated. Much of the information depicted on radar displays has undergone processing of this kind.

The ARTS system, which was extensively discussed in Chapter 2, fulfills many of these data gathering and processing functions for the TRACON controller.

Information About Aircraft

Identification

There has always been a need for controllers to identify aircraft positively so

that instructions can be given the correct aircraft. This function has now been widely automated, but it was not always so. For a time after radar was introduced, a controller might request a change of heading of an aircraft and identify that aircraft positively by noting which aircraft blip on the radar display changed heading appropriately in response to the instruction. Identification has now been largely automated by recognizable signals transmitted between air and ground. This function is contained within the ARTS system. A data block on the radar display beside the symbol or blip denoting the current position of an aircraft also gives its identity. This saves a lot of controller work and removes a potential source of confusion, although call signs that are visually or acoustically similar can be confused (Conrad and Hull, 1964), irrespective of automation.

Flight Level

Following departure from an airfield, aircraft are cleared by the controller to climb to a flight level. In light traffic, this may be their cruising altitude, but in heavier traffic they are more likely to require reclearance through one or more intermediate levels. Formerly aircraft could be at any level between their last reported one and their cleared one, but transponded altitude information (for equipped aircraft), appearing as numerals in the data block for the aircraft on the controller's radar display, automatically updates its actual altitude continuously. This removes uncertainty, facilitating conflict prediction, and curtails the need for spoken messages between controller and pilot. Other displays showing altitude may also be updated automatically. Similarly, aircraft altitude during its final approach is also continuously updated automatically by ARTS. Associated automated warnings of various kinds are provided if it strays from the glide slope, particularly if it is too low.

The aircraft data blocks on the controller's radar display often also include symbols to show if the aircraft is climbing or descending, the absence of a symbol denoting that it is in level flight. These symbols are derived and maintained automatically. They replace the controller's memory and annotations on the flight strips. Aircraft in climb or descent may also be coded differently on tabular displays of the traffic, without controller intervention. Checks for future potential conflicts have then to cover a band of flight levels rather than a single one.

Aircraft Heading and Speed

Aircraft heading is computationally quite complex from the point of view of air traffic control, since it is derived from angles and distances between the aircraft and fixed points on the ground. The heading flown has to take account of wind speed and direction, but it may be presented digitally on the aircraft's data block or on a tabular display. Aircraft speeds may also be depicted digitally within the air traffic control workspace, and speeds and headings may each be

represented relatively by lines attached to the aircraft's positional symbol and derived automatically from computations. The controller's knowledge of the type of aircraft and of its route provide additional information about expected speeds and headings. Therefore these information categories tend to be the subject of relatively few spoken messages.

Reporting Times and Handoffs

A manual method of updating the progress of a flight is for the pilot to report to air traffic control on reaching a predesignated position on a route, or on leaving a particular flight level during climb or descent. In particular, spoken communications were an essential aspect of the handoff of control responsibility from one controller to another as the aircraft left one flight sector and entered the adjacent one. A change of frequency in communications would also be involved. The practice of silent handoffs is widely adopted in some air traffic control regions, in which the air traffic control handoff of responsibility occurs routinely at the sector boundary without any spoken interchange with the pilot until there is a need to make verbal contact for other reasons (e.g., the need to update communications frequencies). In these instances, more automation renders some human procedures redundant by replacing them with some form of continuous updating of information.

Automated systems for handoffs, introduced in the 1970s, simply replaced the requirement for air traffic controllers to verbally communicate when an aircraft moves from one sector to another, with the automated system to accomplish the same goals. It represented a reliable system that had a clear and unambiguously favorable impact on controller workload and communications load. With continuously and automatically updated information about the state and position of the aircraft, such regular reporting points become redundant.

Overlap of Aircraft Data Blocks

In dense traffic, aircraft data blocks may overlap and become difficult to read. A practical form of automation prevents data blocks from overlapping so that all the information on them remains clear, no matter how closely aircraft that are safely separated vertically overlap in the plan view. An alternative solution is to alternate automatically data blocks that overlap. There may be penalties in the form of new sources of human error: without such automation, controllers may expect a given data block to maintain a fixed positional relationship with its associated aircraft symbol and may then compare the relative positions of data blocks to assess the relative positions of aircraft. However, if the automation keeps data blocks separated, it achieves this by interfering with the relative position of each aircraft and its data block, so that the data blocks themselves no longer depict the relative positions of the aircraft.

Communications: Datalink

Applications of automation to communications have concentrated on the quantitative information exchanged between controller and pilot, since this can be readily identified and digitized for efficient automated transmission (in comparison to other aspects of speech communication, such as voice quality, formality, degree of stereotyping, pronunciation, accent, pace, pauses, level of detail, redundancy, courtesy, acknowledgment). The datalink system is designed to replace the traditional audio-voice link between pilot and controller with an automated transfer of digital information (Kerns, 1991; Corwin, 1991). Datalink is already currently in use for transmission of information between aircraft and the airline dispatch center. In the future, it will also provide to the pilot a visual (or synthesized speech) display of clearance, runway, wind, and other key information needed for landing.

Implementation of datalink systems has a number of generic implications. First, at the interface, a datalink system relies on a manual-visual interface both on the ground and in the air. This shift from audio-voice channels has potential workload implications (Wickens et al., 1996). Second, and potentially more profound, datalink has the potential to make available to both controller and pilot digital information from automated agents at either location, of which one or the other human participant may be unaware. For the pilot, datalink may also increase ''head down" time (i.e., visual attention is diverted from primary displays) in terminal areas (Groce and Boucek, 1987). Datalink also reduces both the need for human speech and the reliance on speech for controller-pilot communication. In principle, time is saved, although not always in practice (Cardosi, 1993). Pilots also glean further party-line information that can be very useful to them from overhearing messages between controllers and other pilots on the same frequency to which they are tuned (Pritchett and Hansman, 1993).

Two contrary challenges should be applied to the automation of communications channels. One challenge, which would favor the retention of more human speech, is to demonstrate that the qualitative information contained in human speech cannot be safely eliminated because it is actually essential in terms of either efficiency or safety. The contrary challenge, which could favor the introduction of further automation of speech, is to prove that the judgments based on the qualitative attributes of human speech have no benefit at all, for it is possible that human judgments based on such impressions are sufficiently false that the system is better without them. It is important also to consider the implications of a mixed audio-voice and datalink environment.

Navigation Aids

Ground-based aids that can be sensed or interrogated from aircraft mark standard routes between major urban areas. Navigation aids that show the direction

from the aircraft of sensors at known positions on the ground permit computations about current aircraft track and heading. Data from navigation aids can be used to make comparisons between aircraft and hence help the controller to maintain safe separations between them. The information available to the controller depends considerably on the navigation aids in use. From the point of view of the controller, these functions are highly automated, and the controller has access only to the limited product from them necessary for the control of the aircraft as traffic, showing where they are, how they relate to each other, and whether there are discrepancies between their actual and intended routes, the latter being derived from flight plans and updates of flight progress, some of which are themselves automated.

Implementation of the GPS will enhance greatly the amount and quantity of navigational data derived from satellites. GPS can provide much more accurate positional information than is needed for most air traffic control purposes (e.g., on the order of 10 meters), but its greatest impact will be on traffic currently beyond radar coverage.

Information Displays

Because all the information needed by the controller about the aircraft cannot be presented within the data blocks on a radar display without their becoming too large and cluttered and inviting data block overlap, and because much of the information is not readily adaptable to such forms of presentation, there have always been additional types of information displays in air traffic control, such as maps and tables. In the latter, aircraft can be listed or categorized according to time, flight level, direction, route, destination, or other criteria appropriate for the controller's tasks. Tabular displays of automatically compiled and updated information can be suitable for presentation as windows in other air traffic control displays. Some of these additional displays are normally semipermanent and are maintained automatically. Others containing more dynamic information that is tabulated or in the form of windows are often updated automatically, wholly or in part. Examples include displays of weather information, of serviceability states, of communications channels and their availability, and of the categories of updated information referred to above. CTAS, the suite of automation tools introduced to assist in terminal area traffic management, incorporates extensive reliance on such information displays (Erzberger et al., 1993). As automation progresses, controllers have to spend less time in maintaining these displays, as more of these functions are done automatically for them.

Alerting Devices

Various visual or auditory alerting signals are provided for the controller as automated aids. They may serve as memory aids, prompts, or instructions and

may signify a state of progress or a change of state. Their intention is to draw the controller's attention to particular information or to initiate a response. They are triggered automatically when a predefined set of circumstances actually arises in the course of routine recurring computations within the system. The automation is normally confined to their detection and identification and does not extend to instructing the controller in the human actions that would be expected or appropriate, although this is an intended future development. Such alerting devices aid monitoring, searching, and attending rather than more complex cognitive functions. The human factors problems in their usage tend to concern timing of presentation and methods of display, since this kind of automated aid has the potential to be distracting and should not interrupt more important activities. An additional human factors consideration is the adequacy of computational technology underlying alerting devices.

The minimum safe altitude warning (MSAW) system is a specific example of alerting automation. This system provides an alerting function that is parallel to the ground proximity warning system in the cockpit. MSAW alerts the controller that a conflict with terrain or obstructions (e.g., radar towers) is projected to take place if an aircraft continues along its current trajectory. The projection is based on the aircraft's transgression of a specified minimum altitude during descent segments.

Track Deviation

Controllers spend considerable cognitive effort in searching their displays for track deviations. To reduce the need for searching, computations can be made automatically by comparing the intended and the actual track of an aircraft and by signaling to the controller whenever an aircraft deviates from its planned track by more than a predetermined permissible margin. In principle this can be applied to all four dimensions of the flight: the lateral, longitudinal, and altitude dimensions of the track and its time of arrival at a given location. The controller is then expected to contract the pilot to ascertain the reason for the deviation and to correct it when appropriate and when possible and to issue an immediate instruction if the deviation could be potentially hazardous. The significance and degree of urgency of a track deviation depend on the phase of flight and on traffic densities: it can be very urgent if it occurs during the final approach.

Conflict Detection

One of the principal duties of the controller is to ensure that aircraft do not conflict with each other. This requires the estimation of future aircraft positions. Conflict detection automation is designed to support the controller in this function. Comparisons between aircraft are made frequently and automatically, and the controller's attention is drawn by changing the coding of any displayed aircraft

that are predicted to infringe the separation standards between them within a given time or distance. Introduction of the ARTS system in the 1960s provided a feature that could detect and predict conflicts between aircraft, thus automating what had previously been a vulnerable, effort-intensive human function of trying to visualize future traffic situations. This capability has been extended in order to alert the controller with a visual and auditory alarm whenever two trajectories are predicted to initiate a loss of separation in the future—the conflict resolution advisor. Although occasional false alarms in this system may be a source of irritation (e.g., if the controller was aware of the pending conflict and was planning to resolve it before a loss of separation occurred), controller acceptance of these devices has been generally favorable. Indeed, controllers have expressed specific concern at the loss of these predictive functions when equipment failures have temporarily disabled them (Wald, 1995).

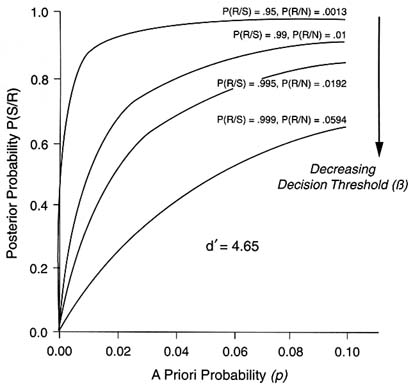

Depending on the quality of the data about the aircraft, a balance is struck in the design of conflict detection systems to give as much forewarning as possible without incurring too many false alarms. The practical value of the aid relies on computational correctness and on getting this balance right. (The necessary procedures for ensuring an optimal balance between false alarms and missed warnings are discussed further in a later part of this chapter.) Sometimes the position or the time of occurrence of the anticipated conflict are depicted, but a conflict detection aid provides no further information about it. Unlike TCAS resolution advisories (described below), which mandate specific pilot maneuvers, no specific action to relieve the alert condition is recommended. The controller is left to resolve the problem in whatever way he or she sees fit.

Computer-Assisted Approach Sequencing and Ghosting

Approach sequencing and ghosting are applied to flows of air traffic approaching an airfield from diverse directions, amalgamating them into a single flow approaching one runway or into parallel flows approaching two or more parallel runways. Computer-assisted approach sequencing depicts on a display the predicted flight paths of arriving aircraft. It shows directly, or permits extrapolation of, their expected order of arrival at the amalgamation position and the expected gaps between consecutive aircraft when they arrive. The controller can issue instructions for minor changes in flight path or speed in order to adjust and smooth gap sizes, and particularly to ensure that the minimum separation standards applicable during final approach are met. Ghosting fulfills a similar function in a different way: the data block of each aircraft appears normally on the radar at its position on its actual route, but it also appears as a ghost with much reduced brightness contrast in the positions on the other converging routes that it would occupy to arrive at the amalgamation position at the same time (Mundra, 1989). In effect, each route depicts all the traffic before route convergence as if convergence had already occurred, showing what the gaps between consecutive

aircraft will be and permitting adjustment and smoothing of any gaps before the traffic streams actually merge. One of the main ways in which these kinds of aids may differ is in the length of the concluding phase of the flight to which they apply. Some deal only with traffic already in the terminal maneuvering area and preparing to turn onto final approach to the runway, and others extend into en route flight and apply to the aircraft from before the start of its descent from cruising until its point of touchdown on the runway. This kind of aid may thus cut across some of the traditional divisions of responsibility within air traffic control, between the en route sector controller and the terminal area controller. It relies on extensive automated computation facilities.

Flows and Slots

Various schemes have evolved that treat aircraft as items in traffic flows and that exercise control by assigning slots and slot times to each aircraft in the flow. Separations can then be dealt with by reference to the slots. The maximum traffic-handling capacities of flows can be defined in terms of slots, and the air traffic control is planned to ensure that all the available slots are actually utilized. One complication is that slots are not all the same size: because of wake turbulence from heavy aircraft, slot sizes vary, and slot adjustment can be problematic at peak traffic times. Tactical adjustments can be minimized by allowing for the intersection or amalgamation of traffic flows in the initial slot allocation. Slots are being widely adopted in European air traffic control, where they have generally been beneficial and have spread delays attributable to insufficient capacity more evenly among users.

Other Automation Systems

In this section we briefly consider some other systems that are either being considered for deployment or are being field tested. Because this is more properly a topic for Phase 2 of this report, only two examples are discussed.

Electronic Flight Progress Strips

Electronic flight progress strips are a particular kind of tabular display intended to replace paper flight progress strips. Being electronic, they can be generated and updated automatically in ways that paper strips cannot be, and the controller must use a keyboard instead of handwritten annotations to amend them (Manning, 1995). Provision is often made to expand visually an electronic flight progress strip while it is being amended in order to see the amendments clearly and to place them correctly on the strip. The approach to the automation of flight strips has essentially been to capture electronically the functions of paper flight strips. This has proved quite straightforward to accomplish in part and impossible

to accomplish entirely, although complete automation of human functionality may not be feasible or necessary. For example, a paper strip is sometimes cocked sideways on the display board as a reminder of an outstanding action to be taken with it, and electronic equivalents of this memory aid could be devised.

There has been concern that some more complex cognitive functions that controllers engage in do not lend themselves so readily to conversion into electronic form. Some human factors problems of design have been posed by difficulties in capturing electronically the full functionality of paper flight strips, which are more complex than they seem (Hughes et al., 1993). However the results of a series of extensive studies examining the use of both paper and electronic flight progress strips do not support the view that electronic strips impair the controller's memory or ability to build up a picture of the traffic (Vortac and Gettys, 1990; Manning, 1995). Further research is needed to resolve these issues.

Center-Tracon Automation System

The center-TRACON automation system (Erzberger et al., 1993) is the newest ground-based automation system and is only now being evaluated at certain operational centers and terminals. Like conflict alerting automation, CTAS is not designed to replace controller actions, but rather to provide an automated means for integrating and displaying information, to assist the TRACON controller with optimally scheduling and spacing aircraft in three-dimensional space on arrival to and departure from the runway. Direct displayed representations that are designed to replace (or augment) cognitive visualizations is a key element. CTAS currently consists of three subsystems, the traffic management advisor (TMA), the descent advisor (DA), and the final approach spacing tool (FAST). CTAS development has involved close collaboration with users and attention to issues of the user interface. Recent human factors evaluations of CTAS subsystems have validated the benefits of this close collaboration with users during the development of the system (Harwood, 1994; Hilburn et al., 1995).

Cockpit Automation

Aviation automation has generally been more extensive and far-reaching in the air than it has been on the ground. Several of the many automated systems that have been introduced in the cockpit have had major implications for air traffic control operations. Accordingly, a discussion of air traffic control automation would not be complete without examining the role of these automated systems.

Aircraft Flight Guidance Automation

Automation of aircraft guidance began with devices for flight stabilization, progressed through simple autopilots, to the high-level flight management system and flight protection systems found in the modern glass cockpit, in which multimodal electronic displays and multifunction keyboards are used extensively (see Billings, 1991, 1996, for an overview). The introduction of these systems has undoubtedly improved aircraft performance. The safety record of modern aircraft is also good, aircraft accident rates having remained relatively stable over the past two decades. The mean time between accidents involving hull loss is substantially higher on glass cockpit aircraft than on the previous generation of aircraft, although the supporting data do not include two recent B-757 accidents (Wiener, 1995).

Although the most mature level of flight deck guidance automation, the FMS (Sarter and Woods, 1994b), is a pure airborne system, it has two important implications for air traffic control automation. First, several important lessons have been learned regarding the human factors of automation introduction, both in design of the interface and in implementing the philosophy of human-centered automation. Second, the tremendous potential power of the FMS to define optimal routes has revealed the limitations of the current air traffic control technology to enable these routes to be flown. Hence, the FMS has served as an impetus for greater authority for route planning and adjustment to be shifted to the cockpit and the air carrier—the issue of free flight. Whether there is pressure to shift authority from the human controller to other system users (as in free flight) or to an automated agent, the human factors implications for the controller—of being removed from the flight control loop—are similar.

Ground Proximity Warning System

The ground proximity warning system (GPWS) was widely implemented in commercial airlines following a series of incidents involving controlled flight into terrain (CFIT) in the early 1970s (Wiener, 1977). The device within the cockpit alerts the pilot when combinations of parameters (altitude, vertical velocity) suggest that the aircraft may be on a collision path with the terrain or not configured for landing. As such, it provides the pilot with clear and unambiguous information to supplement whatever terrain information the controller may be able to provide. Early renditions of the system provided pilots with an excessive number of irritating false alarms; subsequent refinement has reduced their number. The record of the GPWS has generally been a successful one. In the 5 years following its widespread installation in 1975, CFIT incidents decreased dramatically compared with the previous 5 years, for nations that required GPWS installation (Diehl, 1991). Nonetheless, the CFIT problem remains one of the most dangerous facing transport aviation.

Traffic Alert Collision Avoidance System

The traffic alert collision avoidance system (TCAS) is one of the more recent cockpit systems with significant implications for air traffic control. It is a cockpit-based device that allows an aircraft fitted with it to detect other aircraft in close proximity on potential collision courses with it, in time to make emergency avoidance maneuvers, the nature of which is recommended by the device itself. GPWS provides information regarding separation between aircraft and ground. TCAS, however, although also an airborne system, has considerably more direct implications for air traffic control.

Because conflicts between two moving aircraft are far more complex to predict than between a moving aircraft and a static ground object, TCAS algorithms are far more complex, have taken much longer to evolve than those for the GPWS, and are still undergoing refinement (Chappell, 1990). Billings (1996) summarized the impacts of inadequacies of TCAS algorithms, including nuisance warnings in high-density traffic areas. Hence, TCAS has only recently been introduced in force into the commercial airline cockpit.

A TCAS alert should be rare. If it is ever needed, the whole of the normal air traffic control system has in a sense failed to function as planned, since one of its objectives is to ensure that there is no need for emergency maneuvers of the kind that TCAS involves, although TCAS still protects equipped aircraft from aircraft flying under visual flight rules that are not in the air traffic control system. TCAS is also difficult to reconcile with normal air traffic control practices, because all the planning of air traffic control is done on the assumption that aircraft will fly as planned and will not make sudden unexpected maneuvers. A TCAS maneuver therefore always has the potential to generate longer-term problems in solving a short-term and very urgent problem.

Nevertheless, it is a final safeguard, which air traffic control must accommodate in an essentially retrospective way, since TCAS is a very short-term solution from an air traffic control perspective. It therefore has to be handled tactically, and its circumstances are exceptional. Normal conflict detection procedures, and conflict resolution ones if they are available, would resolve a TCAS situation long before it was needed, provided that the basic information had been in the air traffic control system, the system had functioned as planned, and the aircraft concerned had behaved as predicted. If TCAS occurrences become more common, controllers may have considerable difficulty in accommodating their consequences; this would reveal a fundamental flaw in the air traffic control system itself, which would have to be tackled as a matter of urgency.

Not surprisingly, like GPWS, TCAS was initially plagued by many false alarms, which have triggered further efforts to refine and optimize the detection algorithms, in order to preserve pilot trust in the system. However, unlike GPWS, by alerting the pilot to vertical spacing issues and recommending avoidance maneuvers, TCAS in effect shifts authority to an automated agent (and the pilot)

and hence away from the controller, whose primary responsibility is to maintain lateral and vertical separation between the aircraft in his or her purview.

In fact, in two respects this shift has already occurred. First, on some occasions, pilots responding to a TCAS alert may change their altitude radically without informing controllers concurrently (Mellone and Frank, 1993). Second, on some occasions, pilots may use TCAS to adjust their spacing in such a way as to maintain separation just beyond the TCAS alert zone. In both cases, the controller's perception of an erosion of authority, the result of this cockpit-based automated device, is quite accurate.

HUMAN FACTORS ASPECTS OF AUTOMATION

Technology-Centered Versus Human-Centered Design

The design and implementation of automation in general has followed what has been termed a technology-centered approach. Typically, a particular incident or accident identifies circumstances in which human error was seen to be a major contributing factor. Technology is designed in an attempt to remove the source of error and improve system performance by automating functions carried out by the human operator. The design questions revolve around the hardware and software capabilities required to achieve machine control of the function. There is not much concern for how the human operator will subsequently use the automation in the new system, or to how the human operator's tasks will be changed by the automation—only the assumption that automation will simplify the operator's job and reduce errors and costs.

The available evidence suggests that this assumption is often supported: automation shrinks costs and reduces or even eliminates certain types of human error. However, the limitation of a purely technology-centered approach to automation design is that some potential human performance costs (discussed later in this chapter) can become manifest—that is, entirely new human error forms can surface (Wiener, 1988), and "automation surprises" can puzzle the operator (Sarter and Woods, 1995a). This can reduce system efficiency or compromise safety, negating the other benefits that automation provides. These costs and benefits have been noted most prominently in the case of cockpit automation (Wiener, 1988), but they may also occur in other domains of transportation.

For example, automated solutions have been proposed for virtually every error that automobile drivers can make: automated navigation systems for route-finding errors, collision avoidance systems for braking too late behind a stopped vehicle, and alertness indicators for drowsy drivers. No doubt some of the new proposed systems will reduce certain accident types. But there has been insufficient consideration of how well drivers will be able to use these systems and whether new error forms will emerge (Hancock and Parasuraman, 1992; Hancock et al., 1993, 1996). There is a real danger that the automated systems being

marketed under the rubric of intelligent transportation systems, although beneficial in some respects, will also be subject to some of the same problems as cockpit automation. After two decades of human factors experience with and research on modern aviation automation, the benefits and costs of automation are beginning to become well understood.

The technology-centered approach has dominated aviation for a number of years, only to be tempered somewhat in recent years by growing acceptance of human factors in aviation design.2 Several alternative philosophies for automation design, based on the concept of user-centered design, have also been proposed (Norman, 1993; Rouse, 1991). The human-centered approach to automation (Billings, 1991, 1996) has much in common with the concept of user-centered design. This approach has been applied to the design of personal computers, consumer products, and other systems (Norman, 1993; Rouse, 1991). The success of this design philosophy, particularly as reflected in the marketplace, testifies to the viability of the human-centered approach. Its applicability to air traffic control automation is considered later in this chapter; at this point, however, it should be noted that these alternatives to strictly technology-centered design approaches do not mandate human involvement in a system, at any level. Rather, a user-centered approach to the design of a system is a process, the outcome of which could be function allocation either to a machine or to a human. In this sense, the user-centered approach is broader than a technology-centered approach and in principle can anticipate problems that strict adherence to the latter design approach can bring.

Benefits and Costs of Automation

In a seminal paper, Wiener and Curry (1980) pointed out the promises and problems of the technology-centered approach to automation in aviation. They questioned the premise that automation could improve aviation safety by removing the major source of error in aviation operations—the human. In another early analysis of the impact of automation on human performance, Bainbridge (1983) also pointed out several ironies of automation, principal among them being that automation designed to reduce operator workload sometimes increased it. These early papers described some of the potential problems associated with automation, including manual skill deterioration, alteration of workload patterns, poor monitoring, inappropriate responses to alarms, and reduction in job satisfaction. Although Edwards (1976) had earlier raised some of the same concerns regarding cockpit automation, the Wiener and Curry (1980) paper was notable for proposing the beginnings of an automation design philosophy that would minimize

some of these problems and would support the human operator of complex systems—an approach later developed further by Billings (1991, 1996) as ''human-centered automation."

Billings (1991, 1996) has traced the existence of incidents in modern aviation to problems in the interaction of humans and advanced cockpit automation. Many of these problems derive from the complexity of cockpit systems and from the difficulties pilots have in understanding the dynamic behavior of these systems, which in turn is related to the relative lack of feedback that they provide (Norman, 1990).

Since the pioneering Wiener and Curry (1980) paper, a number of conceptual analyses, laboratory experiments, simulator studies, and field surveys have enlarged our understanding of the human factors of automation. For reviews of this work, see Boehm-Davis et al. (1983), Billings (1991, 1996), Hopkin (1994, 1995), Mouloua and Parasuraman (1994), National Research Council (1982), Parasuraman and Mouloua (1996), Rouse and Morris (1986), Wiener (1988), and Wickens (1994). In most of this research, it has become common to point out, as did Wiener and Curry (1980), both the benefits and the pitfalls of automation. Two things should be kept in mind, however, when discussing the problems associated with automation. First, some of the problems can be attributed not to the automation per se but to the way the automated device is implemented in practice. Problems of false alarms from automated alerting systems (e.g., the TCAS), automated systems that provide inadequate feedback to the human operator (e.g., the FMS; Norman, 1990), and automation that fails "silently" without salient indications, fall into this category. Many of this class of problems can be alleviated to some extent by more effective training of users of the automated system (Wickens, 1994).

Second, and perhaps more frequent, a class of problems can arise from unanticipated interactions between the automated system, the human operator, and other systems in the workplace. These are not problems inherent to the technological aspects of the automated device itself, but to its behavior in the larger, more complex, distributed human-machine system into which the device is introduced (Woods, 1993). This is particularly true in the cockpit environment, in which the introduction of high-level automation with considerable autonomy and authority has produced a situation in which system performance is determined by qualitative aspects of the interaction of multiple agents (Sarter, 1996).

The benefits of aircraft automation include more precise navigation and flight control, fuel efficiency, all-weather operations, elimination of some error types, and reduced pilot workload during certain flight phases. Air traffic control automation, which has been more modest to date in comparison to cockpit automation, has provided benefits in the form of improved awareness of hazardous conditions (conflict alerts) and elimination of certain routine actions that allow the controller to concentrate on other tasks (e.g., automated sector handoffs).

TABLE 12.3 Potential Human Performance Costs of Automation

|

Automation Cost |

Source |

|

New error forms |

Sarter and Woods (1995b); Wiener (1988) |

|

Increased mental workload |

Wiener (1988) |

|

Increased monitoring demands |

Parasuraman et al. (1993); Wiener (1985) |

|

Unbalanced trust, including mistrust |

Lee and Moray (1992); Parasuraman et al. (1996) |

|

Overtrust |

Parasuraman et al. (1996); Riley (1994) |

|

Decision biases |

Mosier and Skitka (1996) |

|

Skill degradation |

Hopkin (1994); Wiener (1988) |

|

Reduced situation awareness |

Sarter and Woods (1992, 1994a, 1994b) |

|

Cognitive overload |

Kirlik (1993) |

|

Masking of incompetence |

Hopkin (1991, 1994) |

|

Loss of team corporation |

Foushee and Helmreich (1988); Parsons (1985) |

The benefits of aviation automation, whether in the air or on the ground, are not guaranteed but represent possible outcomes. Nevertheless, the economic arguments that initially stimulate investment in automation are clearly reinforced by the financial return on that investment. In some instances the prospective benefits of automation have accrued independently of any costs, for example, more fuel-efficient flight. Other benefits may be mitigated or even eliminated by the costs. For example, although automation has reduced operator workload in some work phases, the overall benefit of automation on workload has been countered by some costs. Sometimes automation decreases workload only during a short work phase, but not otherwise. At other times, automation increases workload because of increased demands on monitoring or because of the extensive reprogramming that is required. In either case, the anticipated workload reduction benefit of automation is not realized.

Table 12.3 lists the kinds of human performance costs that have been associated with automation. The list is not comprehensive and is not meant to indicate that automation is inevitably associated with these problems (for a more detailed listing of automation-related human factors concerns in the cockpit, see Funk et al., 1996). Rather, the table gives an indication of the kinds of problems that can potentially arise with automated systems. These effects are now quite well documented in the literature, at least with respect to cockpit automation. There is empirical support for each of the effects noted in the table, although the quality, quantity, and generalizability to air traffic control operations of the empirical evidence varies from effect to effect. Given that it is by now almost axiomatic that automation does not always work as planned (or as advertised) by designers, a better understanding of these effects of automation on human performance is vital for designing new automated systems that are safe and efficient. The effects that have been the most well studied are discussed here.

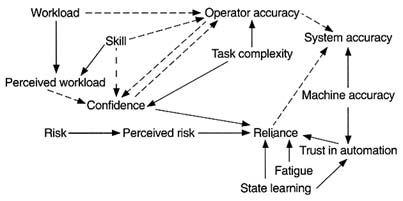

New Error Forms