Dietary Patterns to Prevent and Manage Diet-Related Disease Across the Lifespan: Proceedings of a Workshop (2024)

Chapter: 3 Dimensions of Food Choice and Influences on Dietary Patterns

3

Dimensions of Food Choice and Influences on Dietary Patterns

This session, moderated by Alison Brown, National Institutes of Health, began with two speakers providing an overview of inequities in nutrition and health, including opportunities for intervention during the important period of adolescence. Speakers then discussed access to healthy diets globally and the potential to influence food choice through behavioral economics.

INEQUITIES IN NUTRITION AND HEALTH

If one looks at national trends in adult diet quality, said Cindy Leung, Harvard University, one can see modest improvements from 1999 to 2010, but when the data are stratified by socioeconomic status (SES), it is clear that the gains have been made predominantly by those in the highest SES group. Leung asserted that interventions developed to improve diet quality should be universal but ideally should reduce disparities as well. She defined “diet-related health disparities” as “differences in dietary intake, dietary behaviors, and diet patterns in different segments of the population, resulting in poorer diet quality and inferior health outcomes for certain groups and an unequal burden in terms of disease incidence, morbidity, mortality, survival, and quality of life” (Satia, 2009, p. 2).

While individual factors can influence disparities, Leung continued, her remarks would focus on the structural drivers of food insecurity. She defined “food security” as all people at all times having physical and economic access to safe and nutritious foods that meet their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life. If any of those components

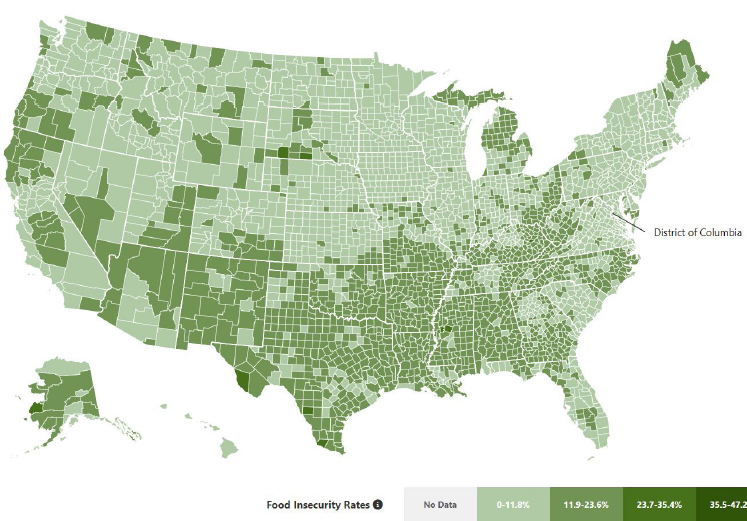

are missing, she stated, it will be at the cost of food insecurity. Leung reported that in 2021, the national prevalence of food insecurity in the United States was just over 10 percent, and that some level of insecurity can be found across the country. She shared a map from Feeding America illustrating the breadth of the issue (see Figure 3-1), adding that those at higher risk of food insecurity include households with children, those headed by a single parent, and Black and Hispanic households. She also clarified that while food security and poverty are correlated, they are not the same thing, and families can experience one without the other.

Food insecurity is absolutely a health issue, Leung argued, with documented consequences, such as higher prevalence of diabetes, poor glycemic control and other medication nonadherence for those with diabetes, higher risk of metabolic syndrome, greater odds of inflammation, and higher prevalence of hypertension. She added that those who experience food insecurity also typically have lower scores for the healthy diet patterns discussed previously (see Chapter 2). The more severe the food insecurity experienced by a family or person, the worse their diet quality is, she noted. When her team studied which specific aspects of diet were affected, they were surprised to find that not just certain food groups but all dietary

SOURCES: Presented by Cindy Leung on August 15, 2023, from Gundersen et al., 2023. Reprinted with permission from Feeding America.

components, as defined by the Prime Diet Quality Score 30-day screener, were in the adverse direction (Wolfson et al., 2022). To learn more about these associations, the researchers conducted qualitative research in the San Francisco Bay Area, asking families which factors affected their ability to feed their children the food they wanted to eat. Key themes emerged from this work, she reported, including how the environment nudges people toward foods that do not support health, how food insecurity requires additional cognitive and physical effort, and how food insecurity serves as a source of toxic stress. Once these factors are understood, Leung argued, interventions can then be developed. She acknowledged the strong network of federal food programs that serve millions of low-income families, allowing them better access to nutritious food, but she also posited that perhaps these programs are not enough.

When the COVID-19 pandemic began, Leung said, she was surprised that food insecurity levels did not spike as early studies had indicated (Wolfson and Leung, 2020). As one of the main reasons for this, she pointed to active mobilizing of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), including an increase in the minimum benefit level, additional administrative support, and an online purchasing pilot. To improve the program even further, SNAP participants surveyed by her team suggested increasing the minimum benefit to $30/month, increasing distribution frequency to biweekly, and subsidizing online grocery delivery fees (Wolfson et al., 2021). Nearly 90 percent of their survey respondents wanted extra money to be used for fruits and vegetables, Leung added, noting that a bill addressing this prospect—the Hot Foods Act1—is currently under consideration.

Leung continued by suggesting that, while food assistance programs are critical to ensuring food security, it may be time to look beyond traditional federal programs. From the Household Pulse Survey, conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, she elaborated, it became clear that when families receive stimulus checks and child tax credits, food insufficiency (a proxy for food insecurity) can be reduced. According to Leung, then, there is an opportunity beyond SNAP to think about economic programs as interventions, which would provide a more robust suite of food and economic policies to help eliminate food insecurity.

Tashara M. Leak, Cornell University, stressed the potential to establish healthful dietary behaviors, partly because in adolescence, individuals start to have more autonomy and purchasing power in making food choices. In low-income households and those that have been racially and ethnically minoritized, she elaborated, adolescents are often doing the grocery

___________________

1 Hot Foods Act, S. 2258, H.R. 3519.

shopping and cooking for the entire family; they may be thought of as children but should be recognized as functioning like adults.

Leak observed that obesity is more prevalent in adolescents than in younger children and is linked to an increased risk of prediabetes in adulthood. Additionally, this risk is not evenly distributed, as there are income and racial disparities in the prevalence of prediabetes nationally (Liu et al., 2022). Leak emphasized the importance of the language used to talk to parents about this issue, as illustrated by her experience trying to convince families that they needed to make changes in their children’s diet because of obesity concerns. She encountered difficulties because of cultural norms around body size and body image, as well as parents’ competing concerns, such as just putting food on the table or finding dependable work. Explaining the linkages between obesity and prediabetes, however, is much more likely to motivate parents to make changes to ensure that their children stay healthy.

Another factor to consider in the diet of adolescents, given their autonomy, is snacking, said Leak. She reported that 23 percent of daily energy intake among U.S. adolescents comes from snacks, and on a given day, 73 percent of adolescents consume items from the snacks and sweets category, such as chips and cookies (Gangrade et al., 2021). Not surprisingly, Leak added, there are even disparities in snacking behavior, such that adolescents from low-income homes consume more added sugar and less whole grains, fruit, and fiber compared with their peers from higher-income homes. She explained that many adolescents face structural barriers—such as an abundance of corner stores offering options that are less healthy but often more expensive—that prevent them from making healthier choices in urban environments. Yet, she pointed out, this is where many adolescents go to purchase snacks. Likewise, between 2006 and 2018, the number of quick-service restaurants located near public schools in urban communities increased from 25 to 34 percent (Olarte et al., 2023), creating even more opportunities for less healthy snacking.

Leak next shared an equity-oriented obesity prevention action framework, with four target areas (Kumanyika, 2019): increasing healthy options through the built environment; reducing deterrents to healthy eating; building on community capacity; focusing on sustainability; and improving social and economic resources.

Leak then shared examples of interventions in schools, clinical settings, and community centers aimed at putting this framework into action. Referring to the previous observation about parents having competing interests, she acknowledged that getting them invested in their children’s nutrition can be difficult. She noted that when parents are worried about their children going hungry or their electricity being shut off, they may consider it an unaffordable privilege to pay attention to foods’ nutritional content. She

also highlighted the importance of not abandoning cultural food norms in an effort to eat healthy, which can further add to disparities. Her programs focus on plant-based dishes in various cuisines and connect nutrition education with culinary education so that adolescents can understand how to make healthy foods in their own home.

For the long term, Leak emphasized the importance of dissemination and implementation of equity-oriented obesity preventing interventions across all settings to promote the interventions’ sustainability. She pointed to opportunities through 4-H partnerships, work on policy with local governments and school boards, collaborations with health systems to help physicians think outside the box in seeking to help adolescents, and partnerships with community organizations and health departments to advance equity efforts in academic infrastructures to address pressing societal issues.

DISCUSSION

Questions and discussions centered around the social and cultural factors related to dietary behavior. Regarding social factors, Leak said it will be critical to collaborate across disciplines and sectors and to acknowledge other components of family life that may prevent families from thinking about nutrition. Simultaneously, she asserted, changes must be made at the policy level. Leung agreed, noting that food insecurity is correlated with the social determinants of health, so it can feel overwhelming to move the needle. She stressed, however, that structural drivers of food insecurity must be addressed. Leung observed that food insecurity is rooted in poverty, structural racism, and many systemic inequities. She added that the field needs to move away from the message that everyone needs to follow the Mediterranean diet to be healthy; rather, all cultures and ethnic groups have respective dietary patterns that can fit within national guidelines. Therefore, she suggested, training dietitians to have sensitivity and understanding when working with different populations and aligning the guidelines with each family’s cultural background can be significant in sustaining the adoption of a healthy diet.

FOOD CHOICE AND ACCESS TO HEALTHY DIETS

Understanding of food choice and dietary patterns in the United States can be informed by data on access to healthy diets worldwide, began William Masters, Tufts University. In economics, he continued, preferences are inferred from observed choices, with price and income elasticities obtained through demand system estimation. He went on to explain that since 2018, new studies have extended the economics toolkit using nutritional data so that analysts can measure a population’s access to a healthy

diet compared with what they actually consume. This new work enables analysts to measure how much it would cost to meet a population’s health needs and whether a healthy diet is affordable using locally available foods. The method is used both within individual countries and globally to monitor change in the number of people who cannot afford a healthy diet, for which the latest estimate from the United Nations was 3.1 billion people worldwide.

The purpose of measuring access to a healthy diet, Masters continued, is to diagnose why unhealthy diets are consumed and identify one of three kinds of remedies. First, when items are unavailable or local prices are high for even the least expensive version of a healthy diet, interventions are needed to improve the supply of suitable items in the food groups identified as unusually expensive or unavailable. At other places and times, availability and prices may be normal, but households have insufficient income to afford enough of even the least expensive items in all the food groups needed for health. In those cases, achieving a healthy dietary pattern is possible only with nutrition assistance. Third, a population may face normal prices and have sufficient income, but the items needed for a healthy diet are displaced by other foods.

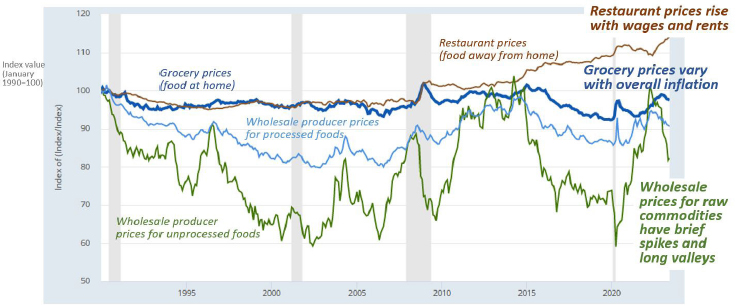

Masters explained that this new method is being applied globally to measure diet costs using computer models to identify the items that are lowest cost and locally available in sufficient quantities to meet each country’s dietary guidelines. This global monitoring uses a composite Healthy Diet Basket (HDB) based on commonalities among all countries’ guidelines, including the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA).2 One key aspect of these modeled benchmark diets, Masters observed, is that they use retail item prices; for consumers, the overwhelming contributor to the cost of a food is not its ingredients but its production and distribution—an observation that is especially relevant for half of consumer spending on food away from home. He also highlighted variation over time in food prices, the most severe spikes occurring in wholesale prices (see Figure 3-2), noting that these spikes, exemplified by the high inflation seen during the COVID-19 recovery period, can result in food crises. Yet even when food prices are low, he stressed, many people cannot afford healthy diets.

Masters described new work focused on the lowest-cost diets that meet dietary guidelines, allowing measurement of access to and affordability of sufficiently nutritious food and distinguishing among three possible causes of poor diet quality: the high cost of nutritious foods, insufficient income to acquire them, and food choice among affordable items. In its 2020 Annual State of Food Security and Nutrition Report, the Food and Agriculture

___________________

2 HDB is a globally relevant dietary standard that reflects the common elements of most national food-based dietary guidelines (Herforth et al., 2022).

SOURCES: Presented by William Masters on August 15, 2023, data from U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (data from August 5, 2023).

Organization of the United Nations included, for the first time, the cost of recommended diets that met 10 different dietary guidelines around the world. Masters shared the costs of the least expensive food items globally. In 2017, for example, the average cost for just the daily energy needed to meet caloric needs was $0.83/day; for the least expensive diet for nutrient adequacy was $2.46/day; and for a healthy diet meeting national dietary guidelines was $3.31/day. This latter diet includes 11 distinct items in six food groups, and while there are commonalities across countries, each country will have a different mix of 11 items that reach the HDB targets for balance based on what is available and widely consumed in that country.

Looking at the cost and affordability of these diets, Masters continued, the findings were stunning even for the lowest-cost diet meeting energy sufficiency. His group found that around 3 billion people worldwide—essentially 40 percent of the global population—cannot afford even this minimalist HDB for energy sufficiency, a point made earlier by Leak. This is the first ability to distinguish between lack of affordability and choice from among affordable options. Most of the unaffordability, Masters elaborated, was found to be due to low incomes, so that healthier diets would require higher earnings, whereas in the United States and other high-income countries, the cause of poor diet quality is food choice among affordable options.

Masters went on to observe that healthy diets being affordable does not mean people are food secure, as these concepts measure different things. He explained that “food insecurity,” as currently measured, means survey respondents had run out of money to buy their usual diet at least once over the previous year. Thus while food insecurity is important, it refers to usual diets consumed and not a dietary pattern that would meet the DGA or other

dietary guidelines, he said. Using modeled diets to calculate what it would cost to meet the DGA, Masters elaborated, reveals whether those usual diets are of low nutritional quality because prices are high, in which case there is an opportunity to intervene on the supply side to lower costs. Thus when costs are normal but incomes are low, intervention with income assistance can provide support. Masters contrasted this situation with one in which people have adequate income to buy the food needed for a healthy diet, but those foods are displaced by unhealthy foods. Masters concluded by listing several potential areas for intervention, including time use, cost of meal preparation, identifying items with the most potential to improve diets, and identifying people who need higher incomes to afford a healthy diet.

IMPROVING HEALTH THROUGH BEHAVIORAL ECONOMICS

It is understood that food is central to health outcomes, began Kevin Volpp, University of Pennsylvania, but fewer than 1 in 10 Americans meet recommendations for the consumption of fruits and vegetables. He added that at the same time, more than 9 in 10 have excess sodium intake, and only 2 percent meet targets for whole grains. He focused his remarks on the behavioral challenges preventing people from eating healthy food.

Volpp stressed the importance of recognizing that rationality can inadequately describe behavior change. People have difficulty making trade-offs between the present and the future, he observed, and decades of research in behavioral economics have shown that the mind has multiple types of behavioral reflexes. He noted that these reflexes are often used to bypass cognition because not every single decision can be weighed by risk, benefit, and probabilities of potential outcomes. He offered three implications for thinking about interventions, recommending consideration of approaches that are based on choice architecture and financial and social incentives instead of just providing information to consumers.

First, Volpp continued, presenting different options and changing default choices can increase the likelihood that people will choose healthy items; examples include providing “opt-out” rather than “opt-in” defaults for programs or listing healthier choices first. He noted that this approach was modeled with a population of people with poorly controlled diabetes who were offered a free program for wireless monitoring at home. One group was offered the opt-in option, while the other was told they were automatically enrolled unless they did not want to be. The study showed that this simple reframing of the invitation tripled enrollment rates, said Volpp; patient engagement and improvements in patient A1C (blood glucose) showed a similar pattern (Aysola et al., 2018). According to Volpp, this research showed not only that low enrollment rates can be improved by framing enrollment as a default for eligible patients, but also that, where

possible, choice architecture can be used to help guide the choice of healthy foods, and that simply shifting some of the default settings in the health record can help clinicians refer more patients to such interventions.

As a second implication, Volpp observed that financial incentives can be highly effective, but their effectiveness depends on design. For example, he continued, a tax on sugary beverages can result in decreased consumption of less healthy choices. He cited a study in Philadelphia showing that a 1.5 cent per ounce tax on sugar-sweetened beverages was associated with a 38 percent net decrease in their consumption (Roberto et al., 2019). Globally, he added, a 10 percent increase in price decreases consumption of such beverages by about 8 percent (Chaloupka et al., 2019). Conversely, he explained, subsidizing healthy foods has not been shown to increase their consumption by much. Part of the challenge here is the asymmetry of gains and losses, he elaborated: if people are not buying healthy foods regularly, they may not pay enough attention to them to notice sales or discounts. Additionally, he pointed out, research in psychology has found that the utility of a dollar lost is roughly twice the utility of a dollar gained, which he said helps explain why price increases have a greater effect than price decreases on utilization. Volpp pointed out that a similar phenomenon is seen in the health system with copayments: when they are raised, health care utilization drops, but when they are lowered, health care utilization does not increase very much. Thus, he stressed, it is important to think critically about the behavioral mechanisms involved and systematically test ways to tap into them. Importantly, he said, the incentives do not need to be large to work, but they need to be immediate, salient, and presented in a way that is easy to understand.

Lastly, Volpp referred to the launching of the American Heart Association’s (AHA’s) Food Is Medicine initiative, funded by the Rockefeller Foundation and inaugural partner Kroger, with a goal of building evidence for scaling these programs more widely. He noted that while lifestyle interventions can be very effective, they are not always covered by insurance to the same extent as pharmaceuticals, which makes them difficult to sustain. Volpp cited a 2002 study showing a lower incidence of diabetes for participants in the Diabetes Prevention Program compared with those on the drug metformin (Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group, 2002); although all insurers covered metformin, it took another 12–14 years for them to cover the Diabetes Prevention Program. Volpp emphasized the double standard involved, in that lifestyle interventions are often covered only if they yield short-term savings, whereas medications are covered if found by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to be safe and effective regardless of their cost-effectiveness.

Volpp acknowledged that important evidence on which to build has been gleaned from the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women,

Infants, and Children; medically tailored meals; and other available programs; however, he argued, much remains to be learned in terms of intensity, duration, delivery, and engagement. He described a research planning group of national experts—with expertise in areas ranging from food as medicine, to clinical trial design, to cost-effectiveness, to behavioral science—that has been charged with thinking about ways to ensure that the AHA initiative will have a large impact. He noted that one of the focal points for the AHA program is human-centered design, focused on better understanding current behavior and rapidly iterating the aspects of the program.

Volpp reported that a cooperative studies model for accelerating learning is being developed. “We want to be able to learn from one another as rapidly as possible,” he explained, “and not wait until the end of each study to find out what happened.” Volpp’s group hopes to maximize learning across pilot sites and use automated trial platforms to facilitate replicating and scaling efforts. The group is just finishing the planning phase for the 10-year initiative, he added, and next will be looking to derisk the larger-scale trials and conduct rapid-cycle testing of feasibility, efficacy, and the like. Overall, he concluded, this initiative will be focused on improving health equity and building programs to be scaled.

DISCUSSION

Participants and speakers highlighted different perspectives on making some of the choices connected to food. Volpp, for example, referred to decision fatigue for those with lower incomes, stating that it is tied to the broader issue of scarcity. Individuals living in poverty are essentially burdened by the taxing of their cognitive bandwidth, and it is difficult to make decisions when one is constantly in cognitive overload. According to Volpp, this is another reason to think deliberately about designing solutions that make it easier to choose healthy foods. From an agricultural perspective, a participant asked if the right foods were being produced. Masters stressed that too little land and resources are devoted to producing fruits, vegetables, and fish. He suggested making land use more inclusive, devising more jobs for people, and creating a smaller climate footprint.

Another participant asked about the cost of housing as context. Masters noted that, when one considers financial precarity, food insecurity, and adverse living conditions, it is clear that the lack of housing for people in the United States is central to structural deprivation. Zoning restrictions add challenges to this deprivation, he pointed out, as do transportation and access to employment. He asserted that all these issues of livelihood and security underlie the overarching challenge of food insecurity.