Dietary Patterns to Prevent and Manage Diet-Related Disease Across the Lifespan: Proceedings of a Workshop (2024)

Chapter: 5 Lessons Learned and Translating Solutions for the Future

5

Lessons Learned and Translating Solutions for the Future

In the final session of the workshop, moderated by Fang Fang Zhang, Tufts University, speakers reviewed interventions conducted by various stakeholders to improve the food environments for consumers and populations of different ages. They also highlighted the work of community-based organizations and their role in influencing food infrastructure, as well as food policy. Finally, speakers discussed legal and policy challenges and opportunities for further improving access to healthy foods and health outcomes.

IMPROVING THE HEALTHFULNESS OF FOOD ENVIRONMENTS

Speakers on this topic highlighted work with corner stores and grocery retailers in Minnesota, lessons learned from research in Baltimore, and opportunities for positioning families to succeed by engaging health care providers more systematically.

Improving Access to Healthy Options

Melissa Laska, University of Minnesota, began by explaining that her work builds on the premise that not all Americans have equal access to healthy food—something that has been known for quite some time. Disparities are clearly cut across race, ethnicity, and income, she observed, and many communities lack access to retail food outlets where they can buy a range of healthy foods at reasonable prices. One of the first solutions tried, Laska continued, was to build new supermarkets in those communities, but while

job creation and new infrastructure came from these initiatives, the research findings were, in her words, underwhelming. Improvements in dietary patterns among the residents living in these communities were not apparent, Laska elaborated; this likely resulted, in part, from overlooking the numerous smaller food stores that play a key role in many communities. She described these small venues, such as bodegas and corner stores, as trusted retailers having numerous touch points with residents. She noted, for example, that one in three customers surveyed when exiting small food stores in Minneapolis and St. Paul, Minnesota, reported that they shop in that store every day. More than 75 percent reported that they shop in the store at least once a week, she added, which is often enough to offer an opportunity for intervention. Laska acknowledged, however, that there are also challenges involved in working with small food stores, as many of these retailers have not built their business model to account for perishable foods, so they face infrastructure limitations and procurement issues in dealing with these foods.

Efforts targeting these stores to promote the availability of healthy foods began around 15 years ago, said Laska, with technical assistance being provided to small food stores, especially for supplying produce. She noted that there was a great deal of both excitement and success in this first wave of work. Research showed changes in customers’ knowledge and attitudes and yielded mixed evidence with regard to changes in purchasing and sales, but implementation challenges impeded further improvements. As one key challenge, however, Laska identified the scalability of implementation, which was highly time and effort intensive. Sustainability issues became clearer over time as well, she added, as effects could be seen during the acute intervention phase in stores, but once that phase had ended, there was often a return to baseline.

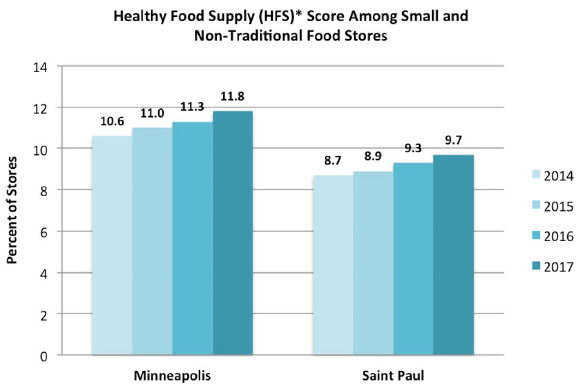

Laska shared an example from Minnesota, where there was a very active corner store program. Discussion at the time was focused on policy levers for grocers and business licenses and how to incentivize participation and leverage the opportunity offered by these small stores throughout the city of Minneapolis. In 2014, Laska continued, the Minneapolis Staple Foods ordinance went into effect, mandating that stores stock minimum quantities of certain healthy staple foods. She noted, however, that following a 5-year study of the ordinance’s implementation, researchers found very small changes in these stores, with no consistent improvements in the nutritional quality of purchases compared with nearby St. Paul, which did not have this ordinance (see Figure 5-1).

Reflecting on this study and the findings reported in other literature on the subject, Laska said her group has had time to think about what direction to take next. She cited a 2022 review looking at retailer strategies that have been tried and tested across heterogeneous supermarket environments, which found mixed results with regard to changes in sales, purchasing,

NOTE: The HFS score is a measure of the overall healthfulness of store offerings. The level of change is seen to be similar in Minneapolis and St. Paul stores.

SOURCES: Presented by Melissa Laska on August 16, 2023, data from Caspi et al., 2020, and Laska et al., 2019.

and dietary outcomes (Wolgast et al., 2022). One of the more rigorously tested strategies in food stores is nutrition scoring, she noted, whereby shelf tags have quantified labels showing how healthy a product is—a strategy implemented primarily in larger-format stores, and one that requires large-scale implementation across product categories. Laska stressed that ultimately, industry often has control over the store environment and product placement. In talking with store owners, Laska and colleagues have found notable evidence of formal and informal agreements with distributors and food manufacturers that include benefits to the retailer, such as free displays and signage to promote specific products. In exchange, the retailer gives control of placement and price back to the industry. She closed with a call to better understand the scope of these arrangements so as to advance in-store research in a meaningful way.

A Focus on Infants and Children

As a Washington, DC, community pediatrician at Children’s National Hospital, Kofi D. Essel, now primarily director of food as medicine at Elevance Health, incorporates nutrition information in his guidance and counseling for patients and families. He acknowledged, however, that this was not always his practice. He related an incident that took place following his interaction with a family and their 4-month-old baby, when he realized that neither he, his colleagues, nor his physician supervisors were

equipped to talk to this family about infant feeding and child nutrition. Essel noted that this realization aligns with the literature, which shows that 71 percent of medical schools do not provide the recommended minimum 25 hours of baseline nutrition education, with a third not providing even half that amount (Adams et al., 2015). Overall, he added, even fellows and attending physicians later in their careers did not feel confident in having these discussions with families around nutrition and diet-related chronic disease. While recognizing that physicians do not need to become dietitians, Essel stated his belief that they should feel comfortable enough with the subject to support families with meaningful and unharmful dietary advice. He also expressed his belief that pediatricians should be comfortable providing nutrition support in the first 1,000 days of a child’s life, which in his view is often a missed opportunity to prepare the child and the family for success later in life. He added that if one waits until the child is older to provide this support, the child is often already a picky eater and has established other challenging habits and patterns.

The difficulty of understanding the best ways to feed young children is compounded when families experience food insecurity, Essel continued. He noted that food insecurity is often triggered when a family experiences a sudden financial hardship. The food budget is affected because it can easily fluctuate, he elaborated, leading to anxiety around meal acquisition and the quality of food, with diets becoming monotonous in turn, and ultimately the amount of food consumed by every member in the household declining. Essel characterized food insecurity in American households as ubiquitous and quite pervasive, but often invisible, so that clinicians are frequently surprised by how pervasive it is when they ask screening questions. Considering the hierarchy of food needs, he observed, just having enough food to feed the family is the most critical concern for many people who experience food insecurity. Essel stressed further that, although the goal of diversifying a child’s diet revolves around offering a variety of foods, there is a good chance that families experiencing food insecurity will be unable to do so because they are worried about wasting money and food. He added that parents enjoy seeing their children happy, so offering foods they know a child already likes makes them feel good, too, and slowly habits are formed around that diet. Essel maintained that infants eventually should eat what adults are eating, but he pointed out that most adults do not eat enough fruits and vegetables and have poor-quality diets overall, thereby perpetuating a cycle that leads to diet-related diseases, a problem that is exacerbated in households experiencing food insecurity.

To address this issue, in 2016, Essel’s health system began screening all children at Children’s National Hospital for food insecurity. Initially, the parents would be given a list of resources, but often they were not useful for families. Accordingly, Essel said, a clinical community partnership called

FLiP, the Family Lifestyle Program, was created. This program brought together Children’s National Hospital, the American Heart Association, and the Young Men’s Christian Association of Metropolitan Washington, with a focus on healthy families and communities, addressing food and nutrition security and diet-related chronic disease through a family-centered lens. FLiP included a food-as-medicine program, with a primary emphasis on produce prescriptions, which involved introducing access to fresh, frozen, or canned produce through vouchers or direct delivery for families. Essel’s group was especially interested in using the program as an intervention to support the health of young children in their first 1,000 days.

Essel described FLiPRx, the company’s produce prescription initiative, a pilot project that involved delivering fresh produce from local farms every other week for 1 year to families who were experiencing food insecurity and those at risk for diet-related disease. FLiPRx also included a variety of nutrition education tools, including community cooking classes. Essel shared some qualitative results of this family pilot project. Fruit and vegetable intake increased, and families reported that they were able to try new foods without worrying about waste, had greater purchasing power, and could better diversify their diet.

In summary, Essel emphasized the importance of understanding that food-insecure households place young children in a stressed feeding environment and typically have poorer diet quality. He added that caregivers need the support of being connected to resources that allow them to expand the children’s dietary options without worrying about wasting what is left uneaten. Finally, Essel argued that such interventions not only help improve the quality of food intake for families, but also offer the kind of multifaceted approach that is necessary for building partnerships, designing focus groups, and creating materials in different languages to reach a wide range of groups in need.

Lessons Learned from Food Environments in Baltimore

Joel Gittelsohn, Johns Hopkins University, highlighted his work in Baltimore to improve the food environment, calling attention to a map demonstrating that 20–25 percent of residents live in Healthy Food Priority Areas (previously called “food deserts”). Those areas not only lack access to healthy food, he pointed out, but have an abundance of unhealthy food resources. He added that the median income is below 185 percent of the federal poverty level, and there is limited access to personal vehicles.

According to Gittelsohn, the food environment in Baltimore is large and complex, with numerous public markets, food pantries, supermarkets, convenience stores, and many more retailers, making it difficult to know how to prioritize his group’s efforts. The group developed four main approaches: changing the availability of healthy options; changing the availability of

unhealthy options; manipulating prices; and addressing location, in terms of both the ability to get to a store and placement of foods within the store. Gittelsohn shared research conducted between 2000 and 2018, noting that most interventions targeted the provider/seller and consumer levels, with some focusing on suppliers such as food banks and wholesalers, but that none of the work touched on policies. Previous studies found that food environment interventions can be effective in addressing key risk behaviors for chronic disease in disadvantaged communities, he acknowledged, by improving access, increasing consumption of healthy foods, and sometimes impacting obesity. His group, however, recognized the importance of multifaceted efforts, integrating educational, access, and policy approaches whenever possible, while emphasizing community engagement at every level.

Describing his group’s current work, Gittelsohn shared five lessons learned, presented in Box 5-1. In closing, he observed that his group has taken 20 years to develop and test solutions for improving the food environment, and that such efforts require both capacity and experience.

BOX 5-1

Lessons from Food Environment Research in Baltimore

- Invest heavily in formative research (i.e., mixed methods; triangulation; emergent, flexible design). Relying on a few focus groups will not be sufficient to secure the multiple perspectives and triangulation needed to understand the whole picture. There is often a disconnect between retailers and consumers, so communication linkages are critical to improving the food environment.

- Engage with communities for the long term. This is not a new lesson, but it can be difficult to do well and requires decades of work. Building ongoing relationships and partnerships in community settings takes time and commitment, but it will build trust and help with sustainability.

- Pay attention to intervention exposure, and ensure that sufficient levels are achieved. Strategies include monitoring intervention delivery, setting standards from the beginning, and modifying plans if the standards are not achieved (e.g., the number of stores to be included or the number of foods to be stocked to realize success).

- Work at multiple levels of the food system (i.e., consumers, retailers, suppliers, policy makers). Different foods, such as healthy produce vs. a bag of chips, will have different distribution systems.

- Consider working at the policy level to support environmental interventions. Doing so can help scale interventions beyond 10 or 20 stores. Digital strategies such as simulation models can also help in decision making and policy assessment by showing the expected benefits.

SOURCE: Presented by Joel Gittelsohn on August 16, 2023.

DISCUSSION

Speakers and participants focused on creating opportunities to bridge communication between retailers and the community and to improve access to alternative sources of produce, such as canned and frozen options. Gittelsohn said his group facilitates conversations as part of its community engagement process and identifies foods that are culturally acceptable for promotion in the stores. But a large part of this community engagement happens during the intervention itself, he stressed, such as by catching someone at the store when they are about to decide on purchases and using strategies such as taste testing. Laska added that it is not uncommon for store operators and customers to have different cultural or racial backgrounds, so it is important to ensure a common understanding of products. Gittelsohn agreed, sharing an example from his initial work in Baltimore in which around 70 percent of small store owners were Korean American, but their customers were primarily African American. There was a range of relationships, he noted, but many experienced challenges in communication.

With respect to produce, Gittelsohn asserted that fresh produce is highly overrated, pointing out that frozen produce is just as good with similar nutrient levels, but it can be much easier to provide to more remote locations. Essel noted that access to fresh produce is also an issue of equity, and many families want items they feel they cannot access. The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children and Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) give families expanded options, he observed, but he agreed that fresh items are overemphasized and too little emphasis is placed on the cost savings that can be realized by purchasing other options.

ROLES OF COMMUNITY-BASED ORGANIZATIONS

Beyond retailers and health care systems, community organizations around the country play important roles in improving access to healthy foods for families and individuals, especially those at lower income levels. Several speakers highlighted initiatives and potential opportunities from the work of food-focused community-based organizations.

Feeding Texas

Celia Cole, Feeding Texas, introduced the organization’s work supporting 21 food banks across the state, noting that millions of Texans participate in food bank programs every year that are offered through a network of 3,000 community partners throughout Texas. While she acknowledged

that it is not possible to “food bank our way out of hunger,” Feeding Texas is leveraging its core strengths beyond meal provision to implement strategies that can improve overall health and well-being. Not only does the organization’s network have a vast infrastructure of warehouses and cold storage facilities, but it also has a strong logistics capacity and maintains relationships across the food industry so it can move food where it needs to go at low or no cost. Approximately 4 million Texans participate in food bank programs every year, Cole explained, and each participant visits the food bank about seven times each year, which translates to 28 million opportunities to gain insight from the people being served. She shared three key strategies by which Feeding Texas is connecting food access with health.

The organization’s first strategy involves ensuring that the food being distributed is as healthy as possible, with a focus on fresh produce. Cole explained that Texas grows an abundance of produce, and much of it goes to waste every year because of imperfections or market conditions. Food banks and Feeding Texas have agreements with growers across the state, she explained, to salvage surplus produce that cannot make it to market, providing a cost-effective way to increase access to produce in low-income communities. The difficulty many Texans face in accessing fresh produce is not just related to money, she observed, noting that many people live in a food desert or an area without access to healthy food. Feeding Texas also uses approaches such as mobile food delivery and home delivery for people who cannot get to a store and connects families to SNAP and other services that can increase their food resources. Feeding Texas has 120 trained case assistance navigators across the state at food banks to help people navigate the complex process of applying for SNAP and other benefits.

Cole described her organization’s second strategy as providing nutrition education. Feeding Texas has a cadre of dieticians who can help people make healthier food choices. Approaches used to this end include, for example, education in food budgeting, cooking classes, and healthy choice pantries. The focus, Cole added, is always on interventions that combine healthy food choices with education to change behaviors, which Feeding Texas has found to be most effective.

Finally, Cole highlighted her organization’s newer role in partnerships with health care providers, hospitals, and clinics to identify and treat food insecurity. This strategy ranges from identifying and diagnosing food insecurity to making referrals to food banks, assistance with benefit programs, and even writing food prescriptions for specific meals.

In terms of future direction, Cole said Feeding Texas is focusing on working with managed care organizations to develop scalable approaches to value-based care and reimbursement models that would create funding to sustain this role. In closing, she, emphasized the importance of public policy and systems interventions to address food insecurity and its root

causes. She highlighted the opportunity offered by the upcoming farm bill to address the adequacy of SNAP benefits, as well as whom the program is serving and how people use the benefits. She argued that both strengthening other income support programs and creating good jobs are inextricably linked to direct food assistance and can indirectly affect food security for families, making these important areas on which to focus policy advocacy.

FoodCorps

Robert S. Harvey, FoodCorps, described the organization’s recent focus on a theory of change that prioritizes efforts targeting the school system to influence connections between food and health. He explained that FoodCorps grounds itself in the belief that if young people are to be agents of their own bodies, interventions must focus on the place where they spend the most time. Specifically, FoodCorps targets the school cafeteria, the largest food infrastructure such efforts can impact, one that Harvey asserted is often overlooked as a potential target. He pointed out that there are seven times more school cafeterias in the United States than there are McDonald’s restaurants. FoodCorps believes, Harvey elaborated, that it has an opportunity to radically transform the ways in which young people, especially people of color, can counter the impact of deep systemic racism through food. The organization seeks to transform “systemic and intergenerational food disease” through three approaches. Describing FoodCorps’ first approach, Harvey noted that its direct services reach about half a million people daily. FoodCorps holds a national orientation to train service members and then deploys them to schools across 17 states and the District of Columbia, providing weekly food education lessons. The second strategy is policy work at the local, state, and federal levels, Harvey continued, encouraging states to offer nourishing meals for all students. A core aspect of this policy work is supporting local procurement, he added, and devising ways in which school districts can work alongside local farmers to build a cyclical ecosystem. This part of the organization’s work serves more than 10 million young people. Finally, the organization’s third approach involves digital advocacy and campaigns, focused on family engagement so as to include caregivers in the journey toward food justice and food literacy.

Wholesome Wave

Brent Ling, Wholesome Wave, echoed the observations of previous speakers regarding the highly complex food system, but argued that much is to be gained by focusing on the demand side of the system. He explained that Wholesome Wave was founded 16 years ago by a food business chef who knew the industry but was facing challenges related to diabetes within

his own family. The organization’s founders, he said, wanted to address the market failure of the lack of availability of healthy, high-quality produce. Since then, he continued, it has learned that shoppers do not want to be treated differently just because they have low income.

Ling went on to explain that Wholesome Wave’s early work spurred the creation of the Gus Schumacher Nutrition Incentive Program (GusNIP), allowing SNAP benefits to be doubled for purchases at farmers’ markets as a permanent feature of U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) policy. However, he noted, SNAP shoppers are often required to go to a special booth to get validated and receive tokens. Vendors then need to know which tokens are eligible for which food items, and when the tokens are used to pay, it is a public sign that these customers are living with low income. According to Ling, these barriers may impede easy access to a market. Ling concluded by asserting that everyone should be able to participate in the same food economy and be able to access healthy food in the same way.

DISCUSSION

Discussion centered on relationships with the health care system and linkages between food programs and health outcomes. In response to the opportunity challenges presented by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services decree regarding screening for social determinants of health, Cole supported recognition of this link and argued that systems and providers need to start building partnerships and infrastructure to facilitate these types of referrals. She added that food banks need to secure resources and partnerships to meet the increasing demand for food, as well as provide the wraparound services needed to advance economic stability and mobility.

Regarding food program findings that relate to health outcomes, Harvey stated that FoodCorps is currently reevaluating its core metrics but has found that young people who have had 10 hours of FoodCorps direct instruction have three times the produce intake of those not having received that instruction. He also highlighted the organization’s measurement of a sense of belonging, finding that young people feel as though they belong in their school environment more when they are familiar with the foods on the cafeteria menu.

Ling said that Wholesome Wave is preparing to release findings from its produce prescription program showing significant improvements in blood pressure, hemoglobin A1C (blood glucose), food security, and positive health care engagement and support for the program by patients. He also referenced the third-year impact findings from GusNIP showing that participants’ fruit and vegetable consumption increased to a level above that

of the average American. Thus the program not only bridged the existing income disparity in this regard but also surpassed it (Gretchen Swanson Center et al., 2023).

Cole added that measurement has been challenging for Feeding Texas, and the organization is working to better document outcomes in addition to outputs. Feeding Texas wants to know if it is truly moving the needle when it comes to food insecurity and advancing economic mobility for the people it serves.

Ling commented that it is an immense burden for a community-based organization to conduct research in addition to the programs it offers. He added that much of an organization’s programming is done in a research vacuum, so any time it is possible to align researchers’ needs with an organization’s needs, the research is likely to be more replicable and more useful to the community.

A final question was asked regarding the messaging about fresh versus frozen produce and how to close the gap in perception of what is good for people’s health and how the food cycle can be transformed to minimize waste. Cole replied that Feeding Texas is working with partners on education about so-called ugly fruits and vegetables and what is perfectly edible and nutritious despite its appearance. Harvey and Ling added that letting participants and patients drive the narrative can be powerful in communicating stories and successes.

LEGAL AND POLICY CHALLENGES FOR INTERVENTION

Jennifer L. Pomeranz, New York University, shared legal and policy opportunities relevant to the workshop discussions and offered several prominent themes. First, she noted the power of experimentation at the state and local levels, which she said is important because in some states, such as Mississippi, state legislatures have withdrawn the ability of local governments to act. Regulatory agencies have been active participants in many of these conversations, she added, but their resources and their authority to act are also limited. The current food environment is nudging people toward unhealthy food, she observed, a point made numerous times during the workshop, and she raised the question of how the healthy option can be made the default. She added that healthy food comes in many forms, but questioned whether consumers can identify healthy food beyond items such as kale? Finally, while she acknowledged that gaps remain in determining how to help all consumers, she highlighted the need to focus on disparities and how to increase people’s access to healthy foods. She shared research and policies related to online food retail, in-store retail, and food labeling, along with regulatory challenges.

Online Food Retail

Pomeranz began by observing that online purchasing has increased in recent years, especially since the COVID-19 pandemic. She shared a study looking at online food labeling that analyzed 10 products across nine retailers involved in the SNAP online purchasing pilot. The researchers found that the four key elements of nutrition facts, ingredients, common food allergens, and percent juice (where applicable) were present and legible for only about 36 percent of products, whereas voluntary marketing claims, such as nutrient content claims, were available for more than 63 percent of products (Pomeranz et al., 2022). Even allergen information, which is a safety issue, was not widely available on products. She added that there were gaps not only across products but also across retailers with respect to what information was available. The same problem can be seen across food products in online retail, said Pomeranz. She believes USDA can drive change to enable better access to important information for consumers, as it regulates SNAP retail stores and can make this requirement apply online. She acknowledged, however, that an act of Congress may be required to make it to happen. Pomeranz added that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulates labeling, which also includes shelf tags. However, she noted, there are arguments over whether online food retail qualifies as labeling, and there is no clear direction on how FDA would regulate in this space. She called for a broader conversation and more research to develop a clear framework for dealing with this issue.

In-Store Retail

Many in-store retailers operate at a very low profit margin, stated Pomeranz, so it is important that any structural changes taking place in stores do not result in the stores’ increasing the price of food or going out of business. She argued that a policy at the state and local levels focused particularly on checkout aisles and endcap displays would nudge consumers toward healthier options. The goal would be to move healthier food to these locations that encourage purchasing, leaving the unhealthy items, such as candy, in their specifically designated aisles. The general idea is that the policy must be based on nutrition criteria, she clarified, not marketing. She suggested that this could be achieved in two ways—through conditional licensing or direct regulation. For conditional licensing, the government could require a license to operate as a food retailer and mandate that, as a condition for maintaining the license, healthy food must be sold in the checkout aisles and endcaps. The second way, Pomerantz continued, would be through direct mandates, as has been done in Berkeley, California. Both approaches are legally feasible and available as ways to effect change,

Pomeranz maintained. There are also some self-regulatory opportunities in this context; Pomeranz gave the example of Raley’s supermarket chain, which created a family-friendly checkout aisle to support consumers. She also highlighted pharmacies, as people often forget they are now SNAP-approved food stores, which can also self-regulate, as CVS did when it made the decision to ban tobacco products from all its stores.

Food Labeling

Moving on to food labeling, Pomeranz again raised the question of whether consumers can easily identify healthy foods. Based on several studies, she said, consumers are confused about what is healthy, and reducing this confusion is key to success. As an example, she noted that 29–47 percent of participants in one study incorrectly identified the less healthy “whole-grain” product as the healthier one—even with access to the nutrition facts label (Wilde et al., 2020). Thus, she maintained, there appears to be a great deal of misunderstanding when it comes to whole versus refined grains, such that it can be difficult for consumers to differentiate between products that contain primarily refined grains with one whole grain and actual whole-grain products. She emphasized that across studies, consumers underestimate the healthfulness of healthier products, so that even when they are available, many people cannot identify them. She cited another study related to popular fruit drink beverages marketed for children, which found that most caretaker-respondents could not identify the drinks with non-nutritive sweeteners, and many thought sweetened flavored waters had no sugar and unsweetened juices did (Harris and Pomeranz, 2021). Therefore, she argued, food labels need to be updated with clear information to prevent such consumer confusion.

Lastly, Pomeranz focused on toddler formula-type drinks targeted to ages 1–3 years. She cited the consensus of professional medical associations recommending against the use of these products, noting that they are unnecessary and expensive, yet they look very similar to infant formula. While labels on such toddler drinks make several structure/function claims, Pomeranz observed, FDA says it does not have the authority to regulate structure/function claims for food. So not only are parents giving these drinks to their toddlers unnecessarily believing they are a healthy choice, but also caregivers may make the mistake of giving them to their infants because of the similarity in packaging and aisle placement. Emphasizing how powerful marketing and labeling can be across products, Pomeranz added that according to one study, more than 50 percent of infant caregivers incorrectly believed infant formula was nutritionally better than breastmilk (Romo-Palafox et al., 2020). In conclusion, she advocated for more opportunities for cross-pollination among retailers, manufacturers,

researchers, and community members and suggested maintaining a focus on institutionalizing programs through Congress to ensure their sustainability across presidential administrations. She stressed that correcting consumer confusion about labels is one of the main priorities for enabling people to make the choices they want for themselves and their family.