Leveraging Trust to Advance Science, Engineering, and Medicine in the Black Community: Proceedings of a Workshop (2025)

Chapter: 2 Keynote: Race-Based Segregation and Environmental Health Disparities

2

Keynote: Race-Based Segregation and Environmental Health Disparities

Highlights from the Keynote Address

M. Roy Wilson, M.D.

- More than 120 years ago, W.E.B. Du Bois recognized that perceived racial differences in health in fact reflect the differences in conditions under which Blacks and whites live. These racial differences in health persist today.

- Redlining in Detroit and other cities has health and other effects that persist to the current day. The impacts of redlining were well documented in terms of COVID-19, with Detroit emerging as an early hotspot for COVID incidence and death. Redlining is also strongly associated with environmental health impacts; for example, a consistent correlation has been found between historically redlined areas from the 1930s and air pollution measured in 2010 in 202 different redlined areas.

- Using a data-informed approach developed by Wayne State faculty called PHOENIX (the Population Health Outcomes and Information Exchange), mobile health units targeted areas with highest risks of contracting and dying from COVID-19. Based on the positive results, the approach is being used with other conditions and has been expanded from the city level to the state level, with screening and food distribution services added.

- Trust is the belief in the competence of a healthcare provider or system to complete a certain task and likelihood of acting in one’s best interest. Distrust is based on a sense that one’s trust has been diminished or violated and is often directed toward a specific provider or healthcare setting. Mistrust is often a general sense of unease or suspicion, which may originate from historical perspectives linked to group identity, personal experience, vicarious experience, and oral histories.

- Medical mistrust is informed by social/racial context. For example, rejection of vaccine trials and uptake is associated with group-based mistrust that is informed by longstanding racial health disparities; documented implicit bias within health care; and rapid development and promotion of a COVID-19 vaccine in a political climate many perceived as hostile.

- Ways to increase trust for COVID-19 vaccination uptake that may have wider application include the need for meaningful partnerships between healthcare/academic institutions and trusted community leaders, especially faith-based leaders; authentic community investment; career development for Black scientists and healthcare professionals; and contextualization of the vaccine with broader historical and contemporary experiences of racism in the healthcare domain and beyond.

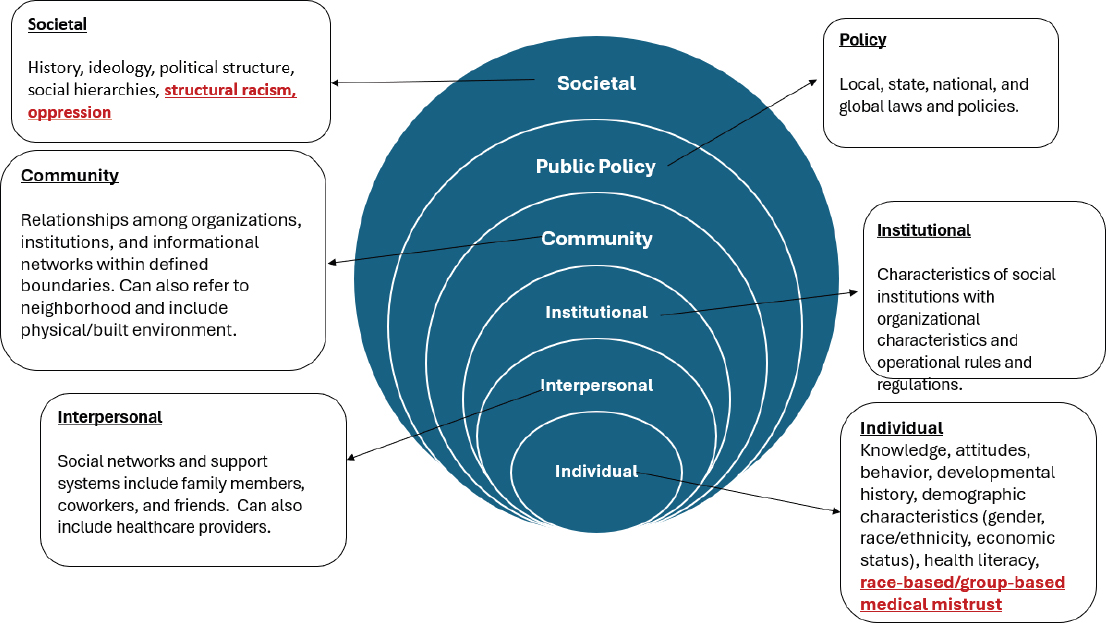

- The Social-Ecological Model is used in public health and underscores the interaction of multiple levels (individual, interpersonal, institutional, community, public policy, and societal) on health. The societal level is where issues of structural racism and oppression arise; the other levels should be examined in the context of social and racial structures.

In the workshop’s first keynote address, M. Roy Wilson, M.D. (Wayne State University), used Detroit, Michigan, as a case study to explain the connections between racial segregation and environmental health disparities. He acknowledged the work of Wayne State faculty Melissa Runge-Morris, M.D., Phillip Levy, M.D., M.P.H., and Hayley Thompson, Ph.D., in presenting on the topic.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT

While John Snow is considered the first epidemiologist for his discoveries during the London cholera epidemic in the 1840s, Dr. Wilson noted the observations made by W.E.B. Du Bois, a Ph.D. sociologist by training (Du Bois, 1899). Dr. Du Bois said racial differences in health reflect the differences in conditions under which Blacks and whites live—what are known as the social determinants of health today. Further, Dr. Du Bois wrote, a higher level of poor health for Blacks was one important indicator of racial inequality in the United States. Racial differences in health have persisted. Dr. Wilson drew on data from Detroit to expand on two themes: racism initiates and sustains health disparities, and segregation affects the health of Blacks more than other groups.

Detroit is the most segregated city in the United States, Dr. Wilson said, and is very heavily African American, with the largest composition of Arab Americans in the country (see Table 2-1). Redlining1 was officially designated by the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) on June 1, 1939, in Detroit and other locations, and it exacerbated segregation. Dr. Wilson recalled that when he first arrived in Detroit, he drove through the city on one of the main thoroughfares to the suburb of Grosse Pointe. “The demarcation was the starkest I had ever seen,” he recalled. Grosse Pointe is an area designated as “green,” or most desirable, under the HOLC grading system, and is almost entirely white today.

In 1941, a concrete wall, called the Birwood Wall (and, colloquially, the Berlin Wall or the Wailing Wall), was built that physically separated Black and white areas of Detroit. Both sides are now predominantly Black, and a portion has been painted with murals, but it remains a reminder of history. Dr. Wilson shared a map that superimposed the original redlining map with 2019 Census data. “The point is the high correlation between the most hazardous areas, according to the HOLC grades, and the areas that have the highest percentage of Black populations,” he said (see Figure 2-1).

Redlining has had a range of ramifications, including those related to environmental health. For example, Dr. Wilson said, there is a consistent correlation between historically redlined areas from the 1930s and air pollution measured in 2010 in 202 different redlined areas. Detroit is a “poster

___________________

1 Per Cornell University’s Legal Information Institute Wex legal dictionary, redlining can be defined as “a discriminatory practice that consists of the systematic denial of services such as mortgages, insurance loans, and other financial services to residents of certain areas, based on their race or ethnicity.”

TABLE 2-1 Population Composition of Detroit

| Black | 83.2% |

| White | 14.4% |

| Hispanic | 8.4% |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 1.7% |

| Native American | 0.7% |

NOTE: Arab Americans are categorized under White in the above data. Detroit has a large, diverse Arab American community.

SOURCE: M. Roy Wilson, Workshop Presentation, December 15, 2022.

SOURCE: M. Roy Wilson, Workshop Presentation, December 15, 2022.

child” for U.S. Rust Belt cities, with high levels of toxic releases, lead, and mercury. One area of Detroit (zip code 48217) is the most toxic zip code in the state and perhaps in the country. As another example, the River Rouge area has 52 heavy industrial sites within a 3-mile area and remains out of federal compliance for sulfur dioxide. Wayne County, in which River Rouge is located, has 4,800 sites with volatile organic compounds (VOCs), most within the city of Detroit. VOCs have been linked to preterm births, and Detroit has the highest rate of such births in the country (15.27 percent). VOCs seep into the groundwater and soil, and they make their way indoors. In 2020, the Great Lakes Environmental Law Center filed a civil rights complaint with the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy on behalf of a number of groups and residents for protection from environmental racism.

The legacy of redlining is also seen with COVID-19. Detroit emerged as an early hotspot for COVID-19 incidence and death, with 10,341 cases and 1,181 deaths in the first 50 days of the pandemic, the highest prevalence in the country.

RESOURCES

Dr. Wilson described a shared data repository developed by Wayne State faculty called PHOENIX (the Population Health Outcomes Information Exchange) as a transformative approach to reduce the burden of chronic disease (Korzeniewski et al., 2020). It includes clinical, social determinant, geospatial, and other data to map disease burden hotspots. The goal is to develop solutions to improve individual health and population-level outcomes. It was initially conceived to monitor elevated blood pressure rates across the city and adapted for COVID-19. With these data, a mobile van targeted areas of high risk, for example, to offer testing. The mobile health unit was so successful that this approach became a strategy across the state, and a fleet of vans is now in operation. It has expanded to offer other screening services, patient navigators who are there to assist, and distribution of fresh food. After early 2020, the huge COVID-19 discrepancy flattened, and it seems that Blacks are doing relatively better in the number of COVID-19 cases and deaths. He urged further study of these data for possible application of the approach to other conditions. As recognition of it, he added, Research!America awarded the Meeting the Moment for Public Health Award to the Michigan Coronavirus Task Force on Racial Disparities in 2021.

Dr. Wilson went on to describe the Social-Ecological Model used in public health, which underscores the interaction of multiple levels (individual, interpersonal, institutional, community, public policy, and societal) on health (see Figure 2-2). “At the societal level, this is where issues of structural racism and oppression come in,” he said. “All of these other levels need to be looked at in the context of social and racial structures.”

TRUST

Dr. Wilson offered the following definitions of trust, distrust, and mistrust in a healthcare context (Griffith et al., 2020):

- Trust: Belief in the competence of a healthcare provider or system to complete a certain task and likelihood of acting in one’s best interest.

- Distrust: Based on a sense that one’s trust has been diminished or violated; often preceded by personal or collective experience or reliable information; and directed toward a specific provider or healthcare setting.

- Mistrust: What or who is not trusted is not necessarily or explicitly named; often a general sense of unease or suspicion, which may originate from historical experiences linked to group identity, personal experience, vicarious experience, and oral histories.

Dr. Wilson urged attention to the general atmosphere of mistrust. A study of Michigan residents showed that African Americans had the highest level of medical mistrust of racial and ethnic groups (Thompson et al., 2021). This translated into lower levels of acceptance related to clinical trials or receiving vaccinations for COVID-19. He noted the study found the following:

Group-based medical mistrust is informed by social/racial context. Rejection of vaccine trials and uptake is associated with group-based mistrust that is informed by longstanding racial health disparities; documented implicit bias within health care; and rapid development and promotion of a COVD-19 vaccine in a political climate many perceived as hostile.

Dr. Wilson shared recommendations from the Thompson et al. study, which may have applications to other areas. First is the need for meaningful

SOURCE: M. Roy Wilson, Workshop Presentation, December 15, 2022, from Moore et al., 2015.

partnerships between healthcare/academic institutions and trusted community leaders, especially faith-based leaders. Second is the need for authentic community investment, such as in community-based organizations that can serve as vaccine research partners. Third is to support career development among Black scientists and healthcare professionals. Finally, quoting the researchers, is the need to contextualize COVID-19 vaccine uptake with broader historical and contemporary experiences of racism in the healthcare domain and beyond.

Dr. Wilson concluded that he is a member of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s Committee on Advancing Antiracism, Diversity, Equity and Inclusion in STEMM Organizations. He called attention to “racism” in the title of the committee as elevating and openly talking about racism. The committee was developing a consensus report at the time of the workshop, which has subsequently been published.2

REFERENCES

Du Bois, W. E. B. 1899. The Philadelphia Negro: A Social Study. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Griffith, D., E. Bergner, A. Fair, and C. Wilkins. 2020. Using mistrust, distrust, and low trust precisely in medical care and medical research advances health equity. American Journal of Preventative Medicine 60(3). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/346912282_Using_Mistrust_Distrust_and_Low_Trust_Precisely_in_Medical_Care_and_Medical_Research_Advances_Health_Equity.

Korzeniewski, S., C. Bezold, J. T. Carbone, S. Danagoulian, B. Foster, D. Misra, M. M. El-Masri, D. Zhu, R. Welch, L. Meloche, A. B. Hill, and P. Levy. 2020. The Population Health OutcomEs aNd Information Exchange (PHOENIX) Program: A transformative approach to reduce the burden of chronic disease. Online Journal of Public Health Informatics. https://doi.org/10.5210/ojphi.v12i1.10456.

Moore, A. R., N. D. Buchanan, T. L. Fairley, and J. Lee Smith. 2015. Public Health Action Model for Cancer Survivorship. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 49(6 Suppl 5): S470–S476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2015.09.001.

Thompson, H. S., M. Manning, J. Mitchell, S. Kim, F. W. K. Harper, S. Cresswell, K. Johns, S. Pal, B. Dowe, M. Tariq, N. Sayed, L. M. Saigh, L. Rutledge, C. Lipscomb, J. Y. Lilly, H. Gustine, A. Sanders, M. Landry, and B. Marks. 2021. Factors associated with racial/ethnic group-based medical mistrust and perspectives on COVID-19 vaccine trial participation and vaccine uptake in the US. JAMA Network Open May 3; 4(5): e2111629. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.11629.

___________________

2 The final report, Advancing Antiracism, Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in STEMM Organizations: Beyond Broadening Participation, was published in February 2023 and is available at https://www.nationalacademies.org/our-work/advancing-anti-racism-diversity-equity-and-inclusion-in-stem-organizations-a-consensus-study.