Leveraging Trust to Advance Science, Engineering, and Medicine in the Black Community: Proceedings of a Workshop (2025)

Chapter: 6 Keynote Address: Closing Health Disparities throughout the National Institutes of Health

6

Keynote Address: Closing Health Disparities throughout the National Institutes of Health

Highlights from the Keynote Address

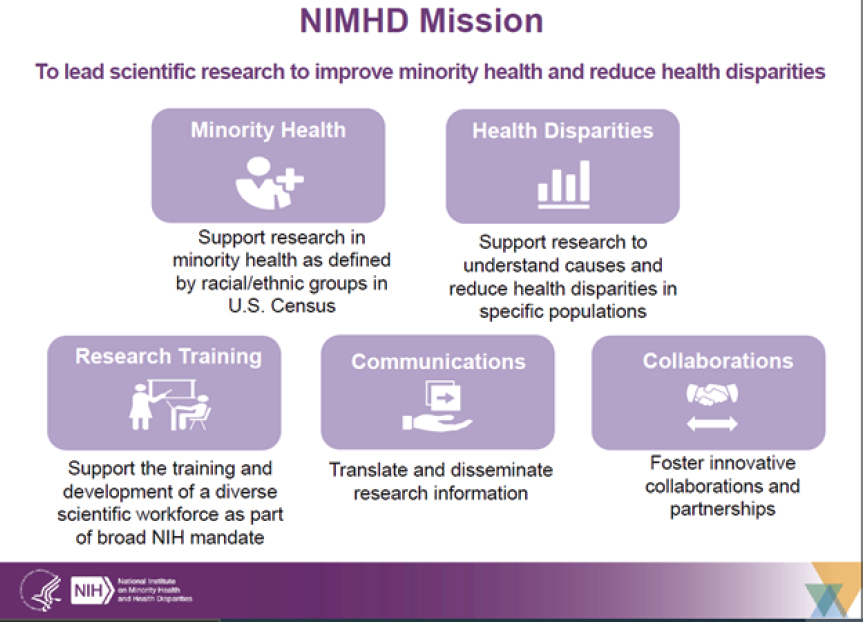

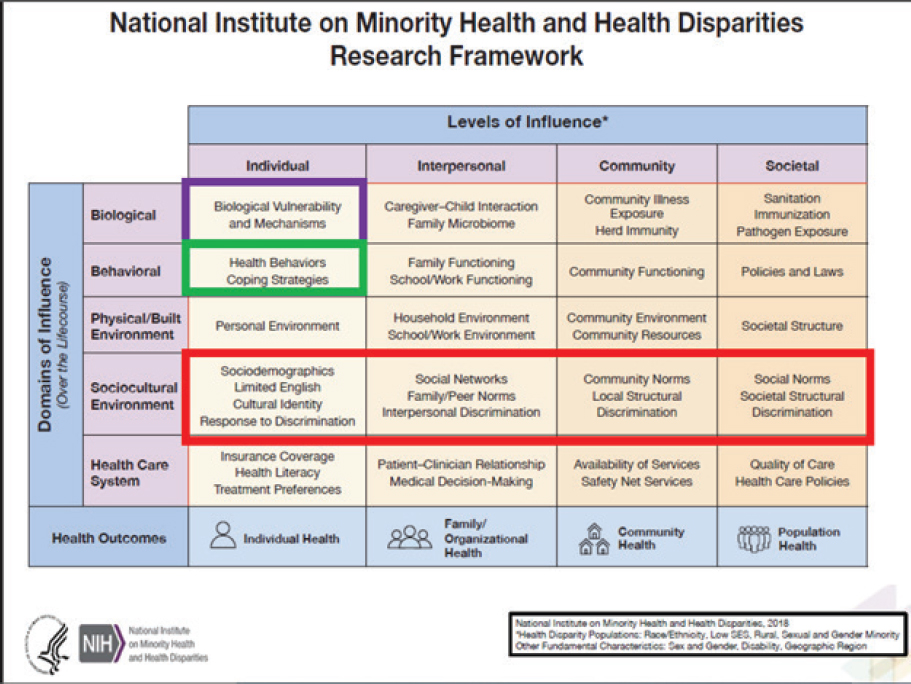

- The National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) is the newest of the institutes and centers at the National Institutes of Health, with a cross-cutting mission to work across NIH to reduce health disparities and improve the health of minority groups, including racial and ethnic minority groups, rural populations, populations with low socioeconomic status, and other population groups. The NIMHD research framework identifies racism and discrimination as notable factors that affect minority health and health disparities across all levels of influence (individual, interpersonal, community, and societal; Webb Hooper).

- NIMHD has conducted two recent intramural NIMHD studies. The first compared genetic and socioenvironmental contributions to ethnic differences in C-reactive protein (CRP) levels using the UK Biobank. Findings showed that socioenvironmental factors contribute more to CRP racial differences than genetics. The second study examined the relationship between cancer survival disparities, genetic ancestry, and tumor molecular signatures in almost 10,000 patients. Four cancer types showed significant survival disparities: breast, head and neck, kidney, and skin. The researchers found that

- changes in gene expression mediated by epigenetic mechanisms have a greater contribution to cancer survival disparities than group-specific genetic variants (Webb Hooper).

- Health disparities are not just differences between any two groups but are conditions that adversely affect groups of people who have systematically experienced greater obstacles to health. They are modifiable, and they do not have to exist (Webb Hooper).

- There is an increasing recognition of the need to get at the root of health disparities by focusing on the social determinants of health. Such determinants are not negative per se. They are the conditions in the places where people live, learn, work and play that affect a wide range of health risks and outcomes. Like health disparities, they are modifiable (Webb Hooper).

- Using the example of lung cancer, racial and minoritized populations face worse outcomes compared with white persons. These outcome inequities are not because of genetic or genomic differences, but because of differences in the likelihood of early diagnosis, surgical treatment, or even any treatment at all (Webb Hooper).

- NIMHD has developed a research framework that conceptualizes the factors relevant to the understanding and promotion of minority health (Webb Hooper).

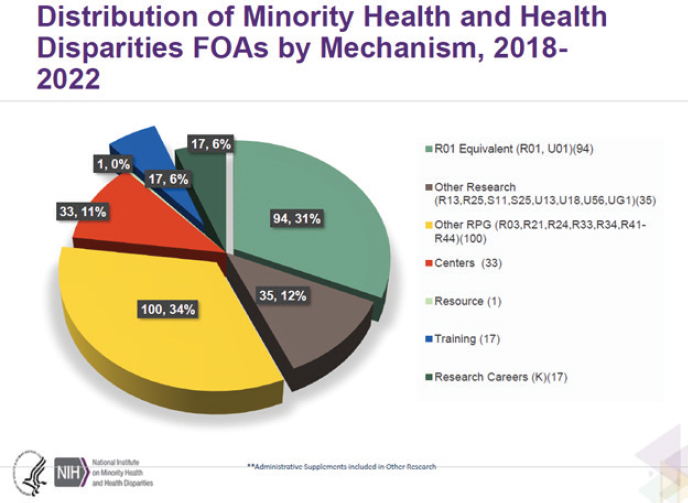

- The number of NIH Funding Opportunities Announcements to support health disparities research has grown from 18 in 2018 to 115 in 2022 (Webb Hooper).

Planning committee co-chair Randall Morgan, M.D., M.B.A. (W. Montague Cobb/National Medical Association), began the second day of the workshop by highlighting the previous presentations from federal agency staff at the Environmental Protection Agency and the National Institutes of Health (NIH; see Chapter 5). He then introduced another NIH leader to provide a keynote address: Monica Webb Hooper, Ph.D., deputy director of the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD). Dr. Webb Hooper talked about what is happening at NIMHD, including opportunities for communities, healthcare providers, and researchers to close health disparities and improve minority health.

INTRODUCTION TO NIMHD

NIMHD is the newest of NIH’s 27 institutes and centers. Health disparities are not new, she said, and they existed well before they were studied or the term “health disparities” was used. “I would argue that they represent a pandemic in their own right,” she stated. NIMHD works across NIH and the entire Department of Health and Human Services to advance the science of health disparities to improve minority health and reduce health disparities (see Figure 6-1). Activities include research, training, communications, and collaborations. NIMHD is disease agnostic and supports cutting-edge science into multiple chronic conditions, as well as the training and development of a diverse scientific workforce. Its extramural divisions encompass (1) Clinical and Health Services Research, (2) Integrative Biological and Behavioral Science, and (3) Community Health and Population Sciences.

Dr. Webb Hooper stressed that health disparities are not just any differences between two groups, but those rooted in disadvantage. She clarified:

A health disparity is a particular type of health difference that is closely linked with social, economic, and/or environmental disadvantage. Health disparities adversely affect groups of people who have systematically experienced greater obstacles to health based on their racial or ethnic group; religion; socioeconomic status; gender; age; mental health; cognitive, sensory, or physical disability; sexual orientation or gender identity; geographic location; or other characteristics historically linked to discrimination or exclusion.1

Another point is that health disparities are modifiable and do not have to exist. The NIH-designated populations with health disparities are Black/African American, Hispanic/Latino, American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian American, Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander, socioeconomically disadvantaged populations, underserved rural populations, and sexual and gender minority groups.

Dr. Webb Hooper shared data on the leading causes of death for Black/African Americans. Diseases of the heart are the most prevalent, at 224.3 per 100,000 people in 2020. Black adults experience a disproportionate

___________________

1 Advisory committee definition of “health disparity,” U. S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2008). Phase I report: Recommendations for the framework and format of Healthy People 2020. Secretary’s Advisory Committee on National Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Objectives for 2020. Washington, DC.

SOURCE: Monica Webb Hooper, Workshop Presentation, December 16, 2022.

incidence of strokes, COVID-19, cancer, heart disease, diabetes, and hypertension burden. These disparities are longstanding and well documented, but there has not been measurable progress, even for diseases that are preventable or treatable. Because understanding and addressing disparities is complex, “I would argue that most of the research to date has been to identify and describe factors that contribute to health disparities, what we call first- and second-generation health disparities research,” she commented.

Using the example of lung cancer, racial and minoritized populations face worse outcomes compared with white persons, Dr. Webb Hooper said. “The roots of these outcome inequities are not because of genetic or genomic differences, but because of differences in the likelihood of early diagnosis, surgical treatment, or even any treatment. Across the board, thus, they are less likely to survive 5 years. To make progress, she suggested drawing on the NIMHD Research Framework, which she said reflects an evolving conceptualization of factors that are relevant to the understanding and promotion of minority health (see Figure 6-2).

Most research to date has focused on individual biological mechanisms to explain poor health and disparities. According to Dr. Webb Hooper, “That singular focus on biology and genetics misses the great complexity of understanding and addressing health disparities, and it does not span the other domains of influence or the levels of influence.” She stressed that the NIMHD Research Framework centers racism and discrimination as notable factors that affect minority health and health disparities across all levels of influence (individual, interpersonal, community, and societal). “That means we have to think bigger and more holistically. Racism worsens health,” she stated. Robust evidence shows that, irrespective of economic status, Blacks receive inferior care, receive biased recommendations associated with physician implicit bias, and are less likely to receive aggressive treatments, pain medications, organ transplants, or offers to join in clinical trials. Thus, there are consequences for only studying health disparities through a biological race model and through an individual biomedical lens. These consequences may include perpetuating the false belief that differences in disease outcomes stem from inherent differences when they are actually social categories. She noted journal articles often include a short discussion of “greater risk” of certain populations without further investigation into the source. The reliance on race and ethnicity as causal determinants of health disparities impedes understanding why these disparities exist and furthers erroneous assumptions that they are biological (and not modifiable) or cultural (the fault of group members themselves).

SOURCE: Monica Webb Hooper, Workshop presentation, December 16, 2022.

The consequences of a biological view of race can also lead to eugenics, misattribution, and a lack of progress, she said.

Dr. Webb Hooper highlighted two recent intramural NIMHD studies. The first compared genetic and socioenvironmental contributions to ethnic differences in C-reactive protein (CRP; Nagar et al., 2021). The researchers compared CRP levels in white and Black people using the UK Biobank. The findings showed that socioenvironmental factors contribute more to CRP racial differences than genetics. This is important, she said, because differences in CRP are associated with racial disparities in some chronic conditions, including type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and lupus. The second intramural study looked at the relationship between cancer survival disparities, genetic ancestry, and tumor molecular signatures in a cohort of almost 10,000 patients (Lee et al., 2022). Four cancer types showed significant survival disparities: breast, head and neck, kidney, and skin. The researchers found that changes in gene expression mediated by epigenetic mechanisms have a greater contribution to cancer survival disparities than group-specific genetic variants (Jordan et al., 2022).

Dr. Webb Hooper lauded the increasing recognition about the need to get at the root of the problems and focus on social determinants of health. “Social determinants of health are not negative per se,” she said. “They are the conditions in the places where people live, learn, work, and play that affect a wide range of health risks and outcomes.” She stressed that both social determinants of health and health disparities are by definition modifiable. “Social determinants of health can operate to drive effective health promotion and well-being in advantaged groups, such as through clean air, clean water, and good schools, while driving health problems in disadvantaged groups. I call these factors adverse social determinants of health.” Dr. Webb Hooper explained that the goal is for everyone to have positive and protective determinants in their lives.

As one resource to measure social determinants of health, Dr. Webb Hooper pointed to a vetted toolkit called the PhenX Toolkit.2 Released in 2020, it provides established measures to help standardize and improve data collection and facilitate harmonization of data across studies. She expressed hope that standardized data collection will improve the ability to share and combine data from multiple studies to facilitate translational research and effective interventions.

___________________

2 See www.phenxtoolkit.org.

FUNDING OPPORTUNITIES

Dr. Webb Hooper said NIH is increasing funding opportunities in health disparities research, from 18 in 2018 to 115 in 2022 (see Figure 6-3). These funding opportunity announcements (FOAs) are one measure that indicate the growing NIH interest in this area. Most were research project grants, but there were also training and career-development grants.

As an example, an FOA solicited applications to study the effect of structural racism on minority health and health disparities through observational and intervention research. Twenty-five institutes and centers participated. There was a robust response, with 163 applications received and 38 awards made. Of the 38 awardees, 20 recipients are either early-stage or new investigators who proposed to cover a wide range of diseases and conditions; 62 percent focused on multiple groups among those designated by NIH as populations with health disparities, and the highest single focus group was African American at 21 percent.

New FOAs published in 2022 also feature cross-cutting themes, diseases, and emphases. A notable number highlight the importance of inclu-

SOURCE: Monica Webb Hooper, Workshop Presentation, December 16, 2022.

sive participation in research. Six exemplars of cross-cutting themes funded are (1) Maternal Health Research Centers of Excellence, (2) Addressing Racial Equity in Substance Use and Addiction Outcomes through Community-Engaged Research, (3) Preventive Interventions to Address Cardiometabolic Risk Factors in Populations that Experience Health Disparities, (4) Prevention and Management of Chronic Pain in Rural Populations, (5) Increasing Uptake of Evidence-Based Screening in Diverse Populations across the Lifespan, and (6) Understanding and Addressing Misinformation among Populations that Experience Health Disparities.

Training supports the development of a diverse and well-trained research workforce though a multitude of opportunities. NIMHD views its diversity supplement program as a way to contribute to this research cohort. She called attention to several T, F, and K awards for undergraduates, graduates, postdocs, residents, and early-career researchers.

She also called attention to two R01 funding opportunities. The first is entitled Health Care Models for Persons with Multiple Chronic Conditions from Populations that Experience Health Disparities (PAR-22-092). The second is Leveraging Health Information Technology to Address and Reduce Health Care Disparities (PAR-19-093). She also noted the value of the Health Disparities Research Institute, one of NIMHD’s flagship training opportunities. It supports the career development of early-career researchers and stimulates research through lectures, small group sessions, mock grant reviews, seminars, meetings with NIH staff, and consultation on developing research ideas into applications. She welcomed participants to apply or to refer others.

“There is so much work to be done, and many opportunities to get involved,” she concluded. She invited participants to connect with her and others at NIMHD.

REFERENCES

Jordan, I. K., K. K. Lee, J. F. McDonald, and L. Mariño-Ramírez. 2022. Epigenetics and cancer disparities: When nature might be nurture. Oncoscience 9: 23–24. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncoscience.555.

Lee, K. K., L. Rishishwar, D. Ban, S. D. Nagar, L. Mariño-Ramírez, J. F. McDonald, and I. K. Jordan. 2022. Association of genetic ancestry and molecular signatures with cancer survival disparities: A pan-cancer analysis. Cancer Research 82(7): 1222–1233. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-21-2105.

Nagar, S., A. Conley, S. Sharma, L. Rishishwar, I. Jordan, and L. Mariño-Ramírez. 2021. Comparing genetic and socioenvironmental contributions to ethnic differences in C-reactive protein. Frontiers in Genetics 12. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fgene.2021.738485.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2008). Phase I report: Recommendations for the framework and format of Healthy People 2020. Secretary’s Advisory Committee on National Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Objectives for 2020. Washington, DC.