Leveraging Trust to Advance Science, Engineering, and Medicine in the Black Community: Proceedings of a Workshop (2025)

Chapter: 5 Federal Response to Health Equity and Environmental Justice

5

Federal Response to Health Equity and Environmental Justice

Highlights from the Presentations

- Establishing the Office of Environmental Justice and External Civil Rights within the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) elevates these issues on par with those of the Offices of Water, Air Pollution, and others (Kumar).

- The EPA is developing 10 indicators of environmental and health disparities that the agency can directly or indirectly influence (Kumar).

- The Inflation Reduction Act provides $3 billion to EPA to award environmental justice grants to community-based organizations, as well as funding for greenhouse gas and other programs of interest. This is a funding level at orders of magnitude larger than EPA has had in its history to support environmental justice (Kumar).

- Executive Order 12898 required each federal agency to identify and address, as appropriate, the disproportionately high and adverse environmental and human health effects of its programs on minority and low-income populations (Kumar).

- Communities negatively affected by redlining in the 1930s are those that today are predominantly Black or Brown in population, have more environmental stressors, and have higher levels of cardiovascular deaths (Gibbons).

- The National Institutes of Health (NIH) Climate Change and Health Initiative is a cross-cutting effort to reduce health threats from climate change across the lifespan and build health resilience in individuals, communities, and nations around the world, especially those at highest risk (Gibbons).

- ComPASS is a new paradigm for funding across NIH to address a range of topics related to the social determinants of health (Boyce).

- Lessons learned include how to involve communities from the start, the value of investments in capacity, and the need for NIH to build trust and engagement (Boyce).

Wayne J. Riley, M.D. (SUNY Downstate Health Sciences University), served as moderator of a session on U.S. government policies and programs. He saluted colleagues, particularly his mentor, Louis Sullivan, M.D. In introducing Chitra Kumar, M.P.H. (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency [EPA]), Gary Gibbons, M.D. (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [NHLBI]), and Cheryl Boyce, Ph.D. (Common Fund, National Institutes of Health [NIH]), he commented that experience shows that the federal response to health equity and environmental justice cannot be taken for granted.

ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY

Ms. Kumar presented on the Office of Environmental Justice and External Civil Rights at the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, where she has been director of the Office of Policy, Partnerships, and Program Development since 2021. She recognized the efforts of those who have worked at EPA on these issues for decades, in particular, Onyemaechi Nweke. The office was set up to address two prongs of environmental justice: fair treatment and meaningful involvement.

Ms. Kumar explained how these terms are defined at EPA:

- Environmental justice is the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws.

- Fair treatment involves the equitable distribution of resources and benefits to communities suffering the greatest disproportionate impacts, preventing and mitigating harms, and eliminating systematic barriers to achieving healthy and sustainable communities for all people.

- Meaningful involvement involves agency decision-makers seeking out and facilitating engagement by potentially affected people about issues concerning their environment or health and providing opportunities for potentially affected people to participate and influence those decisions.

These definitions were formulated in 1992 around the time that the Office of Environmental Equity was established at EPA. In 1994, the Clinton administration changed the name to the Office of Environmental Justice when Executive Order 12898 was signed.1 This executive order required each federal agency to identify and address, as appropriate, the disproportionately high and adverse environmental and human health effects of its programs on minority and low-income populations. This was an important and seminal action, Ms. Kumar commented.

Going forward 30 years to the present, “this administration is supercharging this work,” Ms. Kumar continued. As a result of decades of work, “now we are in a place where we are taking enormous strides in integrating environmental justice into our work.” At the beginning of the Biden administration in 2021, two executive orders have helped—Executive Orders on Advancing Racial Equity and on Tackling the Climate Crisis at Home and Abroad.2 These orders have been inserted into specific agency documents that help embed and integrate those policy ideals into things that will last and transcend beyond this administration, such as EPA’s strategic planning document. “This is the dry stuff, but it matters for how we budget, how we decide about allocation of human and financial resources, and what kinds of outcomes we track,” she said.

Another development was a commitment by the EPA administrator to form the Office of Environmental Justice and External Civil Rights, which takes up different parts of EPA that focus on these issues and gives them

___________________

1 Executive Order on Federal Actions to Address Environmental Justice in Minority Populations and Low-Income Populations, EO 12898, issued February 11, 1994.

2 Executive Order on Advancing Racial Equity and Support of Underserved Communities through the Federal Government, EO 13950, issued January 20, 2021; Executive Order on Tackling the Climate Crisis at Home and Abroad, EO 14008, issued January 21, 2021.

the same status as the Office of Air, Office of Water, and other components within EPA. This enables environmental justice and civil rights to go “toe to toe in decision-making when there are judgment calls related to health and the environment,” she explained.

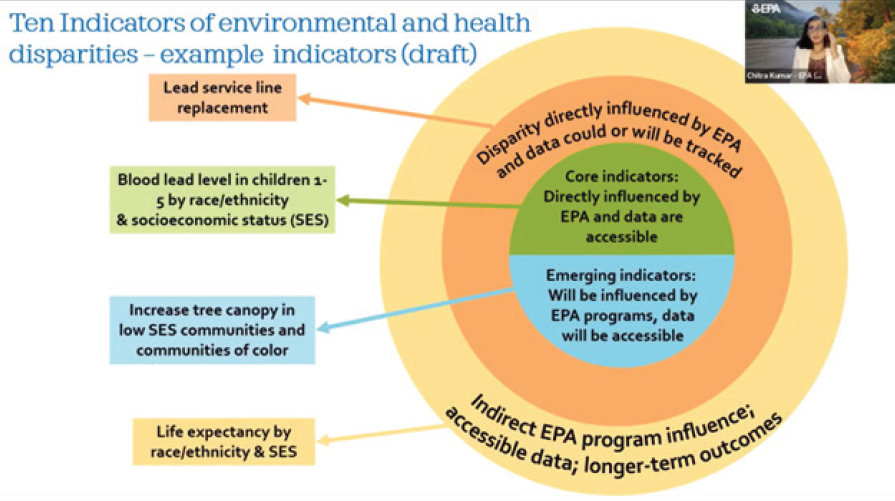

EPA’s principles have always been stated as “follow the science, follow the law, and be transparent”; to this is added “advance justice and equity” as an overarching ideal, which she characterized as a huge accomplishment because it drives decision-making. The strategic plan further places “take decisive action to advance environmental justice and civil rights” within its seven principal goals. Ten indicators of environmental and health disparities that EPA can directly or indirectly influence are under development (see Figure 5-1). In this effort, a workgroup is looking at all of EPA’s regulatory and budgeting work and communicating in words that people can understand. For example, it could be tracking the quantity of lead service lines that are replaced or the increase in tree canopy in low socioeconomic communities and communities of color. The goal is to push for outcome measures to drive decision-making.

EPA is also leveraging the administration’s commitment, such as Justice40, the Climate and Economic Justice Screening Tool, and the Environmental Justice Scorecard. Ms. Kumar also pointed out the funding behind these goals. Through the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of 2022 (P.L. 117-169), $3 billion in environmental justice grants will go to polluted communities. Congress has mandated that community-based organizations be involved to receive grants.

According to Ms. Kumar, this is a transformative investment at EPA that will empower communities to confront and overcome persistent pollution challenges in underserved communities, and aggressively advance environmental justice efforts in such areas as air pollution monitoring, prevention and remediation, mitigating risks of extreme heat and wildfires; climate resiliency; and reducing indoor air pollution. “It’s what communities have been asking for,” she added, noting the program is orders of magnitude larger than EPA has had. She clarified that $2.8 billion will be provided in grants by 2026, and $200 million will be provided as technical assistance for communities that are not yet equipped to get federal money. The EPA base budget also includes $100 million to improve and enhance the agency’s ability to infuse equity and environmental justice principles and priorities into all EPA practices, policies, and programs. EPA has access to other relevant IRA funding besides the environmental justice grants, she reminded the group, including for greenhouse gas reduction, climate

SOURCE: Chitra Kumar, Workshop Presentation, December 15, 2022, based on EPA data.

pollution reduction, reduction in air pollution in ports, methane emission, and heavy-duty vehicles, among others.

NATIONAL HEART, LUNG, AND BLOOD INSTITUTE

Dr. Gibbons shared information on advancing heart, lung, blood, and sleep research with a focus on climate and health research at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Climate change—resulting in rising temperatures, more extreme weather, rising sea levels, and increasing CO2 levels—is having and will continue to have health effects, he began. There is variation in terms of sensitivity, exposure, and adaptive capacity, often affecting the most vulnerable communities and individuals. The key is to build resilience and adapt to changes. The data show why climate change is a priority for NHLBI.

Extreme heat is associated with an estimated 6,000 to 7,000 excess cardiovascular disease (CVD) deaths, with greater mortality increases seen among men, the elderly, and non-Hispanic Black male adults, he reported. There is a compounding and convergence of risks among those who have high CVD mortality and health disparities, many of whom live in Black and Brown communities.

As an example, the District of Columbia shows the link between historical and structural factors and the trajectory of health outcomes. Housing policies from the 1930s resulted in redlining,3 underinvestment, and a multigenerational echo to this day with the Northwest part of the city predominantly white and the Southeast part predominately African American. Heart failure deaths are 172.5 deaths per 100,000 Black residents compared with 61.9 deaths per 100,000 white residents. The legacy of redlining shows up both locally and nationally in the correlation between disinvested urban areas and exposure to environmental threats, such as fewer trees and hotter surfaces. “We are clearly facing an emerging and growing threat that will affect the most vulnerable communities,” he summed up.

As Dr. Gibbons explained, NIH, like EPA, is part of a whole-of-government strategy in which each agency’s portfolio is looking through a lens of climate and health, with an emphasis on health equity through the NIH

___________________

3 Per Cornell University’s Legal Information Institute Wex legal dictionary, redlining can be defined as “a discriminatory practice that consists of the systematic denial of services such as mortgages, insurance loans, and other financial services to residents of certain areas, based on their race or ethnicity.”

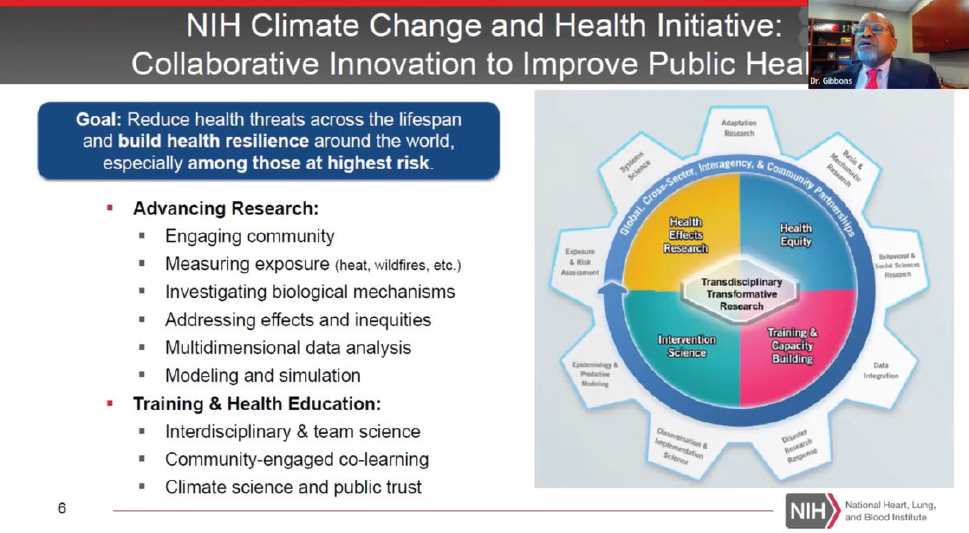

Climate Change and Health Initiative (see Figure 5-2).4 It encompasses advancing research, training, and health education. The research will engage communities, measure exposure, investigate biological mechanisms, address effects and inequities, conduct multidimensional and cross-disciplinary data analysis, and perform modeling and simulation. The training and education will build on interdisciplinary and team science, community-engaged co-learning, and climate science and public trust. “The goal is to reimagine a multilevel, systems approach, leveraging and pivoting from lessons of the pandemic to catalyze discovery for public health,” he concluded. New opportunities for novel interventions abound to predict, prevent, and preempt disease for healthier communities.

NIH COMMON FUND

Dr. Boyce introduced Community Partnerships to Advance Science for Society (ComPASS), which is part of the NIH Common Fund. Taking a step back, she explained that the Common Fund fosters catalytic, transformative, synergistic research across all of NIH.5 It supports high-risk, high-reward experiments to try out things that are different. ComPASS fits in this category because it leverages structural interventions and multisectoral partnerships with a focus on the social determinants of health (SDOH) to improve health outcomes, reduce health disparities, and advance health equity research. These are important to NIH but have not happened in such a large way at NIH, she said. It is important to have this cross-NIH approach, she pointed out, because not only do SDOH affect many sectors, but also “human beings are not divided up by [NIH] institutes; we must think of the whole person.” She continued:

Addressing health disparities and advancing health equity is a profound challenge that involves many sectors and extends beyond the reach of traditional healthcare settings. Social determinants of health are a major contributor to health disparities and operate on a continuum from fundamental structural causes to individual and family circumstances. Addressing fundamental, structural causes of health disparities offers the greatest opportunity to advance health equity and eliminate health disparities.

___________________

4 For more information, see https://www.nih.gov/climateandhealth.

5 For more information on the NIH Common Fund, see https://commonfund.nih.gov.

SOURCE: Gary Gibbons, Workshop Presentation, December 15, 2022.

Dr. Boyce reminded the group that structural interventions “attempt to change the social, physical, economic, or political environments that may shape or constrain health behaviors and outcomes, altering the large social context by which health disparities emerge and persist” (Brown et al., 2019; see Figure 5-3).

NIH is now looking at the effect of structural influences on health outcomes that include the criminal justice system, universal basic income programs, high-speed broadband internet, and community revitalization investment, areas not usually associated with NIH.6 The funded projects will be community led and community engaged to change the process by which research has traditionally been conducted and funded.

NIH listened to communities in ways it has not done before, Dr. Boyce said. This included taking the time to work with community members to plan the listening sessions themselves. In October and November 2021, more than 500 attendees participated in eight sessions. The goals of ComPASS are to catalyze, deploy, and evaluate community-led health equity structural interventions that leverage partnerships across multiple sectors to reduce health disparities, as well as to develop a new health equity research model for community-led, multisectoral structural intervention research across NIH and other federal agencies. It is composed of three initiatives: Community-Led, Health Equity Structural Interventions, or CHESIs; Health Equity Research Hubs (Hubs); and a ComPASS Coordination Center. The program will span 10 years (two 5-year periods). Twenty-five communities will be funded directly, and they will bring in the research partners. Five Hubs will assist the communities with technical assistance, capacity building, and other elements that will help with success. The Hubs will also provide a bridge between the interventions and the Coordination Center, which will be the repository for data. They have 2 years to plan, then several years to conduct their intervention, then 3 years to work on sustainability and uptake and inform public health. There was a high response rate to the solicitation, with awards expected to be made in 2023.

Another new Common Fund program that Dr. Boyce called out is the Advancing Health Communication Science and Practice program.7 Misinformation is not new, but COVID-19 underscored the problem and the need for improved health communications.

___________________

6 See OTA-22-007—Announcement for ComPASS at https://commonfund.nih.gov/sites/default/files/OTA-22-007.pdf.

7 For more information, see https://commonfund.nih.gov/healthcommresearch/strategicplanning.

SOURCE: Cheryl Boyce, Workshop Presentation, December 15, 2022.

Dr. Boyce shared lessons learned from ComPASS to date. First, from the start, it is important to use methods that are designed for participation, feedback, and engagement with partners; involve communities and other partners in setting priorities and feasible approaches for research; and consider implementation and sustainability. Second, building researcher and community capacity for health equity interventions is a critical investment. Third, community-driven health research requires trust and engagement.

DISCUSSION

Dr. Riley lauded these significant, but perhaps not well-known, programs across the agencies and asked the panelists how the Roundtable members and workshop participants can help get the word out to communities. Dr. Gibbons noted the important role that Congress plays in appropriating funds, and advocacy and championing are important. Ms. Kumar noted that potential cross-agency collaboration. For example, EPA is helping to set up Thriving Communities Technical Assistance Centers, which are co-funded with the Department of Energy, with the goal to help them know where they can access public funds. Dr. Boyce added that President Biden’s executive orders have allowed for agencies to have a shared mission and work together on environment and health.

In response to a question, Dr. Boyce clarified that the Common Fund defines community-based organizations very broadly, to include health centers, churches, housing organizations, fraternities and sororities, and many others.

In reflecting on the sessions held during the first day of the workshop, planning committee co-chair Cedric Bright, M.D. (East Carolina University), noted that Dr. M. Roy Wilson (Wayne State University) also talked about the relationship between redlining, pollution, and health outcomes (see Chapter 2). He reminded the group about the negative effects of mistrust and distrust, and the examples about how the medical system has been deleterious to the lives of Black men and women (see Chapter 3), and the need for education, self-advocacy, and learned intermediaries (see Chapter 4).

REFERENCE

Brown, A., G. X. Ma, J. Miranda, E. Eng, D. Castille, T. Brockie, P. Jones, C. O. Airhihenbuwa, T. Farhat, L. Zhu, and C. Trinh-Shevrin. 2019. Structural interventions to reduce and eliminate health disparities. American Journal of Public Health 109(S1): S72–S78. https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/10.2105/AJPH.2018.304844.

This page intentionally left blank.