Leveraging Trust to Advance Science, Engineering, and Medicine in the Black Community: Proceedings of a Workshop (2025)

Chapter: 4 Building Trust in SEM Institutions

4

Building Trust in SEM Institutions

Highlights from the Presentations

- COVID-19 can offer lessons learned on the impact of mistrust of science, the need for disaggregated data, and the value of having Black scientists and others with credibility communicate information about prevention and treatment (Morial).

- The National Urban League’s State of Black America report includes an Equality Index that draws from 300 sets of data to document progress of Black and Latino Americans relative to white Americans (Morial).

- A Pew Research Center study found that, compared with white and Hispanic adults, Black adults have mixed views about the impact of science and are less likely to see it as mostly positive. Relatively few respondents felt science was “mostly negative,” but most had a nuanced idea that it could be both positive and negative (Anderson).

- While Black science, technology, engineering, and mathematics professionals could point to support they received in their STEM education, almost one-half (48 percent) reported at least one negative incident related to race or ethnicity (Anderson).

- Mistrust of the system and differential healthcare outcomes stem from more than historical experience or the social deter-

- minants of health. They stem from the disrespect that Black people experience in the healthcare system today (LeNoir).

- The African American Wellness Project was formed to strengthen Black individuals to become advocates for the prevention, diagnostics, and treatment they are due as patients in the U.S. healthcare system (LeNoir).

- Education and empowerment are necessary before a person enters the healthcare system, which is one of the goals of the Delta Research and Education Foundation (Collins).

- To strengthen trust, there is a need to acknowledge that racism is real, train more physicians and scientists of color, and find ways to decrease bias for those already practicing as well as for trainees. Physicians, along with community health workers and others, can also serve as trusted voices in the community (Collins).

- Encouraging Black youth to enter STEM fields will require mentors, or people in those fields to essentially walk them through (Anderson).

- Expanding research to be more inclusive is important. The Delta Research and Educational Foundation is working to correct misinformation and mistrust by recruiting 1 million diverse participants for clinical trials, including African Americans (Collins).

- A more informed population can advocate for themselves. Education and empowerment are needed to overcome mistrust and miscommunication in the community (Collins).

- One way to build trust and communication is to involve African American physicians in the community with academic medical institutions (Bailey).

- Fighting the stigma to discuss and treat mental health is essential to the overall health of Black Americans (Bailey).

The next workshop session, “Miscommunication and Mistrust,” included presentations and discussion on strategies to increase awareness, support, and participation in science, engineering, and medicine (SEM). Moderated by Silas Lee, Ph.D. (Xavier University), panel participants were asked to identify methods and strategies to build trust in SEM among African American communities. Marc Morial, J.D. (National Urban

League), and Monica Anderson (Pew Research Center) shared data and resources, followed by discussion with Michael LeNoir, M.D. (African American Wellness Project), Rahn Bailey, M.D. (Louisiana State University [LSU]), and Yvonne Collins, M.D. (Delta Research and Educational Foundation).

CONSIDERATIONS OF MISCOMMUNICATION AND MISTRUST

In considering the topic of miscommunication and mistrust, Mr. Morial said he immediately thought of the beginning of the pandemic. Right before the shutdown, he recalled attending a community event where a Black parent shared the belief, gleaned from the internet, that Black people cannot get COVID-19. Not only was this not true, Mr. Morial said, but the data would soon reveal the disparities of COVID-19 deaths and hospitalizations. The data were not easy to obtain. It took great effort to demand release of disaggregated data to understand what was occurring in the Black community, Mr. Morial said. In addition, as research on a vaccine began, it was important that clinical trials were diverse and reflective of the Black community. At the same time, given historical experiences, many people are reluctant to participate in clinical trials.

In his discussions with officials from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and from the National Institutes of Health about increasing vaccine acceptance rates, Mr. Morial related their initial idea was to use celebrities and sports figures as spokespeople. He countered that Black scientists and others with credibility on this issue were needed. The National Urban League and other partners assembled the Black Coalition Against COVID to correct the record and provide culturally competent feedback to the government, healthcare providers, and the community on how to communicate about prevention and treatment of the disease.

According to Mr. Morial, COVID-19 provides a case study on how misinformation and miscommunication based on previous racially motivated stereotypes can cause people to make bad choices, embrace wrong assumptions, and further feed distrust. “We must take away from COVID—and it is not over—lessons learned,” he said. He added that Rep. Karen Bass (now mayor of Los Angeles) worked with scientists of color on a needs assessment to understand the consequences. He called for an in-depth examination of lessons learned to adjust, affect, and reform the public health system in this country.

Mr. Morial pointed to an annual report researched and produced by the Urban League entitled State of Black America, which includes an equality index that measures social and economic disparities across 300 sets of data (National Urban League, 2022). “We’ve been doing the index for almost 20 years, and the change is glacial,” he said, and he concluded:

When I am told that racism is over or problems no longer exist, I do two things. I acknowledge the progress, because this is how we reaffirm our ancestors, our predecessors, those who led this important struggle. But I also point to the data, which shows that disparities are still a reality in American life.… A body of research by our community for our community is crucial and important. We try to elevate it.

SURVEY OF BLACK AMERICANS AND STEM

Ms. Anderson shared data compiled by the Pew Research Center on Black Americans’ views and experiences with science and attitudes about science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) overall. The report by the nonpartisan, nonadvocacy organization was released in spring 2022 (Pew Research Center, 2022). She noted that the survey about Blacks and Hispanics’ trust and engagement with science was supplemented with six focus groups. She highlighted some of the quantitative and qualitative results.

Ms. Anderson explained that participants were asked their views about whether Blacks had achieved the highest levels of success in different fields and whether these fields seemed welcoming to Black people. Athletes and musicians were viewed as being able to achieve the highest levels of success, while scientists, medical doctors, and engineers were among the lowest on both counts (see Figure 4-1).

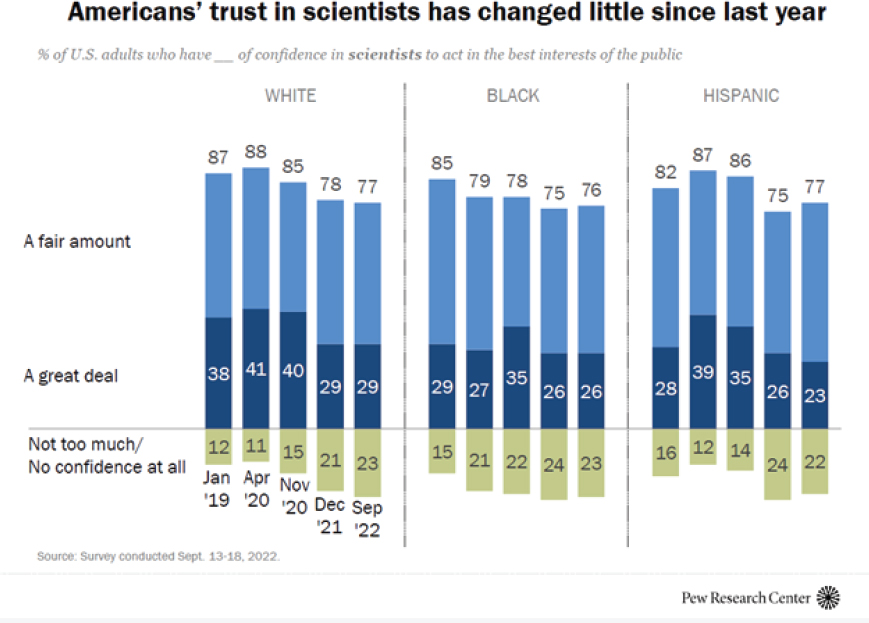

Another set of questions was aimed at opinions about the effect of science on society. Compared with white and Hispanic adults, Black adults have mixed views about it and are less likely to see science as mostly positive. She added that relatively few respondents felt it was “mostly negative,” but most had a nuanced idea that science could be both positive and negative. She also noted that while trust has declined in all groups since 2019, a big driver in the decline is based on the views of white Republicans.

Respondents were asked about their personal experiences with health care, and specifically to rate the quality of care of their most recent healthcare experiences. Most Black Americans (6 in 10) felt their experiences were very

SOURCE: Monica Anderson, Workshop Presentation, December 15, 2022, based on Pew Research Center data.

good or excellent, which was similar to the population overall, although there were differences by income level. However, she also called attention to negative experiences—such as having to speak up for care or feelings of disrespectful treatment—especially among younger Black women. Of this group, 41 percent said their women’s health concerns were not taken seriously, and about half said their pain was not taken seriously. Focus groups drew out some of these experiences, Ms. Anderson related. For example, a Black woman said she recognized built-in biases in the medical field, while a Black man commented, “I just don’t feel like there are enough doctors who have been looking out for our people historically.”

Lastly, Ms. Anderson reported on diversity in STEM occupations. Respondents were asked about their most recent STEM schooling. For those in STEM jobs, most said someone encouraged, challenged, or excited them. But even as Black STEM workers reported encouragement from mentors or advocates, 48 percent also reported at least one negative experience in their STEM education: that is, being treated as if they could not understand the STEM subject, made to feel they did not belong in the class, or encountering repeated negative comments or slights about their race or ethnicity.

Ms. Anderson concluded with comments from the focus groups about the importance of representation in STEM. For example, one Black woman shared she had never had a Black science or history professor, “so I was like, what am I doing here?” A Black man, when asked how to encourage Black teens to enter STEM fields, stressed that “they need examples. They need mentors. They need people in those fields to essentially walk them through. I always tell my youth, it’s easy to do something when you’ve seen it.”

DISCUSSION

Building on the presentations from Mr. Morial and Ms. Anderson, Dr. Lee facilitated a discussion with Dr. LeNoir, Dr. Bailey, and Dr. Collins by posing a series of questions about how to enhance the Black community’s trust and confidence in SEM. Dr. Lee began by sharing the experience of an African American cardiologist who recalled overhearing, as a student, a white student’s comment that “African Americans should be patients and not doctors.” This is the cultural baggage that Black practitioners carry with them, he said.

Missing the Mark

Dr. LeNoir said he formed the African American Wellness Project almost 20 years ago out of the rage he felt about the way Black people are treated in the healthcare system.1 He said the Pew data provide an external look, but he shared what he called an internal look at this issue. When he convened a meeting of Black health experts in the Bay Area, he asked the participants to share any personal experiences when they received disrespectful treatment in the healthcare system. Almost everyone had an experience to relate. Today, he asserted, “health equity is hot,” and many explain the trust issue in terms of historical experience, but almost everyone in their surveys ascribes their discomfort and mistrust to situations that are happening now, not what happened at Tuskegee or other things historically. Barriers and bias are part of the whole system, not just the doctor, Dr. LeNoir said. He continued that navigating the system from the top down will not change the dynamic. “The African American Wellness Project has pushed that we have to change the healthcare system from the bottom up. That means you have to be ready to go into the system. You have to fight for yourself to get the outcomes you want,” he asserted.

He also noted that medical journals regularly publish about diseases that have disproportionate outcomes for Black patients, with genetics and social determinants sometimes given as the reason. He countered, “We at the African American Wellness Project look at the way you are treated when you enter the system that results in the kind of outcomes you have for almost any chronic disease.” He noted in Veterans Affairs studies in which Black and white veterans receive the same diagnostics and treatments, Black patients often do better than they do in the civilian healthcare system. “In summary, if we are treated the same, the outcomes are the same. Sure, there are social determinants that we must be concerned about, but it is the way we are treated once we enter the healthcare system that results in poor outcomes for any chronic disease,” he stressed.

Dr. Collins explained that the Delta Research and Educational Foundation (DREF) is working to correct misinformation and mistrust by recruiting 1 million diverse participants for clinical trials, including African Americans.2 Many researchers claim these populations will not meet their criteria, follow the protocol, or have other excuses. Twelve communities are the focus of a DREF educational effort with local providers and community

___________________

1 For more information, see https://aawellnessproject.org.

2 For more information, see https://www.deltafoundation.net.

members. “All the mistrust has caused avoidance of the healthcare system, and thus delays in prevention, diagnosis, and treatment,” Dr. Collins said. “We have to go way back before people get to the hospital. It’s about preparation.” It is important to understand why people do not want to go to a hospital or have trust in providers, she said. She added that for those who enroll in clinical trials, education is key. “With a more informed population, then you have a population who can advocate for themselves,” she said. She agreed that Black providers and patients experience racism. She recalled as a medical student at the University of Florida, she did not have any overt experiences with racism, but she had many reminders, beginning with the formerly segregated bathrooms in the basement of the school buildings. “Education and empowerment are how we hope we will overcome some of the mistrust and miscommunication we have seen in the community,” she said.

Dr. Bailey recalled an experience when he was chair of the psychiatry department at Wake Forest University in 2015. When the new cancer center director convened a meeting between faculty and local African American private-practice doctors to discuss how to enroll more African American participants in trials, the doctors related they had never been invited to Wake Forest for any such activity. A series of engagements to discuss and share experiences over the past five decades followed. Large institutions can help decrease the stigma and acknowledge systematic wrongs to help make African American patients feel valued and heard by all. “The reality is [there is] a lot we can do to address wrongs; they have not gone away,” he said.

Creating and Implementing Trust

Asked by Dr. Lee for suggestions for how to strengthen trust, Dr. Collins offered three points. First, she said, acknowledge that racism is real. Second, it is important to look at how to train more physicians and scientists of color. Third, for those already practicing but especially for trainees, it is important to find ways to decrease bias.

Dr. LeNoir reiterated his pessimism about top-down efforts. “We have to prepare Black people to go into the system and be their own advocates,” he stated. “If a doctor or other provider seems to disrespect you, or you do not know how to navigate the system, you are already behind the curve.” He urged people to get angry if they receive poor treatment and not to be passive. In this respect, he expressed hope that young people may be changing the dynamic.

Ms. Anderson pointed out that the idea of “being your own advocate” was voiced in the focus groups. However, one person commented that she did not know what to ask for. Hispanic patients or family members may have a language barrier, while some people have jobs that make it difficult to go for second opinions or seek other services. She also noted that younger Black women say they are using online communities and social media to share experiences to bring conversations to light.

Voices to Leverage Trust and Information

Dr. Lee commented that quite often, practitioners in the medical sciences tend to stereotype who should be used as messengers, as Mr. Morial pointed out. Dr. LeNoir stressed that people who are vetted by the community are those the community will trust. Regarding COVID-19 vaccines, large healthcare systems that never attempted to have personal contact with the Black community “all of a sudden want you to get a shot.” Black physicians can speak to the Black community effectively, he said, but traditional media seldom call on them. “You have to be vetted, you have to be trusted; otherwise, the messages go flying by,” he said.

Cedric Bright, M.D. (East Carolina University), asked how to best grow and educate Black students so that they do not perpetuate harmful behaviors. In medical education, there is a proclivity to imitate one’s teachers, he posited. He asked how to break the cycle. Dr. Bailey responded that finding ways to alter a deleterious culture is timely. The culture is antagonistic to diversity, he said, not just racial and ethnic diversity, but also a diversity of new ideas. Money flows to the same types of studies, and change to create a more diverse, free, and open environment is impeded. However, he continued, the reality is that new students coming into medicine are different—in terms of gender diversity, work-life balance, and other factors. He noted he is the first African American chair of any clinical or basic science department at the LSU School of Medicine in New Orleans, where he has been fighting for even incremental changes to increase chances for more people of color to access residencies or receive promotions. “The challenges are often based on the irrationality of not having done so before,” he said. “There must be some external pressure for change in schools across the country.”

Dr. LeNoir lauded the link between talent in the community and academic institutions, as Dr. Bailey recounted in his experience in North Carolina. It is important for every African American physician to engage

with academic institutions, he said. “They [institutions] are not necessarily going to invite you in and they are not necessarily going to keep you there,” he said to Dr. Bailey. “We need people of your caliber bridging the gap.”

Dr. Lee reflected on the comments about the need for vetting, diversity in the research community, and understanding cultural diversity. Dr. Collins called for vetting not only physicians but also community health workers and others who can talk in their community about health issues as trusted voices. Dr. Lee agreed that community activists act as validators with whom residents interact daily. In all communities, there is a communications network that people rely on, and there is a danger in people relying on “Dr. Google” for health information and behaviors. He commented that during COVID-19, many chronic conditions became acute. Dr. LeNoir observed that people were scared to go for regular screenings, although in the Bay Area, traditional systems such as churches, fraternities, and sororities worked to vaccinate people. He suggested podcasting, Facebook, BlackDoctor.org, and other methods for African American providers to reach the community and fight misconceptions.3

Dr. Bailey pointed out the need to address the issue of stigma related to health, and especially mental health concerns. He noted patients are often hearing messages about mental health that are deleterious to best practices. “I learn to hear what they are not saying, what the parameters are, what the real obstacles and hurdles are to getting optimized care,” he said. “This is a huge issue in all medicine in our community, and especially when it comes to mental health.” Dr. Lee noted the intersection between physical and mental health must be addressed yet is often overlooked.

Creative Ways to Build Trust and Educate People

Dr. Lee solicited other ideas for how to build trust and inform people correctly about why they must engage in proactive health strategies. Dr. Collins noted the value of really listening with an emphatic ear. Often, doctors are prescriptive, but they must listen to what is important to the patient. “What’s important to the patient ultimately gets at what’s important to health,” she said. Dr. Bailey added that patients come into a healthcare setting with emotional baggage from poor treatment or not being

___________________

3 BlackDoctors.org is “the world’s largest and most comprehensive online health resource specifically targeted to African Americans.” For more information, see https://blackdoctor.org.

heard in the past. There is also fear or a perception of a power differential, especially among older patients. He also urged stopping the flow of adverse power distribution, so that the patient is the most important. He urged that doctors consider themselves the “learned intermediary” between the patient and the decision. It is a challenge, but it can be done, he said.

Dr. Bright followed up with a question about informed decision-making in which the patient has an active role in decisions about their own health. Dr. Collins gave an example in her work as an oncologist talking with patients about clinical trials. As a scientist, physician, and oncologist, she may see the promise of a clinical trial’s small improvement in outcomes, but a patient may see the potential toxicity, financial costs, and side effects and reach a different conclusion. “What we think is a positive study is very different for the patient. As we have those conversations, we have to lay out the options. Many physicians are not comfortable with that,” she said.

Concluding Comments

Dr. Lee summed up the session. First, there are many delineations of race and racism in society, including cultural and behavioral racism dealing with stereotypes in diverse communities. Second, there is a need to be honest and acknowledge what has happened in the past that causes mistrust and how to address it. Third, creative ways are needed to reach diverse communities on a consistent basis. Validators and community influencers can share information and inform people. The patient wants to be an active participant and not a bystander in the process of getting treatment and their own needs, he pointed out. Decreasing biases means acknowledging the hidden rules of medicine, which impose mental and emotional barriers. Another critical element is to develop communications strategies in this multimodal world to reach people in diverse communities who are often marginalized and misunderstood. “We have to navigate an environment where biases and stereotypes still exist. Cultural dexterity is needed to respond to people in this complex world. Medical professionals need this cultural dexterity, sensitivity, and competence,” he concluded.

Roundtable member Louis Sullivan, M.D. (Sullivan Alliance) reinforced and commended the comments about enhancing patient involvement in decision-making. While there have been improvements in technology and the science base, health disparities have not improved because where “we have not done as well as we should is empowering the patient.” As he noted, the old paternalistic model does not work if people

are to erase inequities in their health status so that patients are the guardians of their own health.

REFERENCES

National Urban League. 2022. State of Black America. http://soba.iamempowered.com/soba-books.

Pew Research Center. 2022. Black Americans Views of and Engagement with Science. https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2022/04/07/black-americans-views-of-and-engagement-with-science/.