Storms from the Sun: The Emerging Science of Space Weather (2002)

Chapter: Color Plates

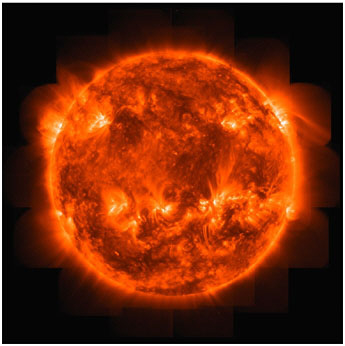

The Sun is an intensely magnetic body and that magnetism is revealed in the bright field lines and loops of plasma suspended in the atmosphere. NASA’s TRACE satellite snapped the many images that make up this composite view of the Sun. Courtesy of NASA.

Million-degree plasma hangs in looping magnetic field lines near the visible surface of the Sun. These loops stretch nearly 300,000 miles high. Scientists hope to learn how the solar atmosphere is heated to 300 times the temperature of the surface. Courtesy of NASA.

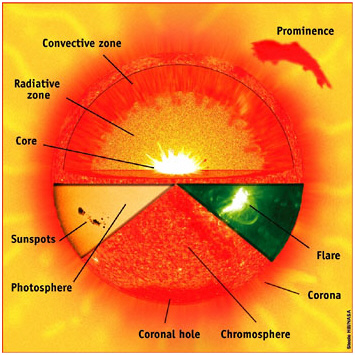

This artist’s conception shows the principal parts and layers of the Sun, using some real imagery from the SOHO satellite. Image created by Steele Hill for ESA/NASA.

A large, eruptive prominence extends more than 35 Earth diameters above the surface of the Sun in July 1999. Viewed here in ultraviolet light by SOHO, prominences are dense clouds of plasma trapped in the Sun’s magnetic field. Eruptions of these loops are often associated with solar flares and coronal mass ejections (CMEs). Courtesy of ESA and NASA.

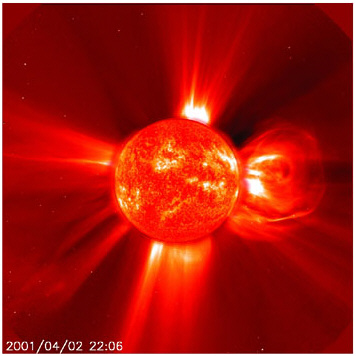

This image offers a composite view of the Sun in April 2002, when a CME lifted off (right side) and caused space storms on Earth. Since 1996, instruments on SOHO have enabled scientists to view the Sun 24 hours a day, creating new images every few minutes. Courtesy of ESA and NASA.

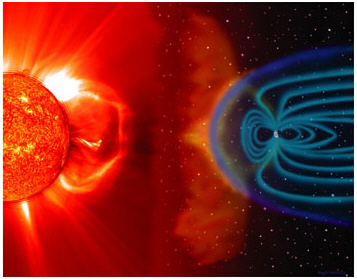

An artist’s conception of a CME and its subsequent impact at Earth. The blue paths emanating from the Earth’s poles represent some of its magnetic field lines which deflect most of the energy and plasma of the CME. (Not drawn to scale.) Image created by Steele Hill for ESA/NASA.

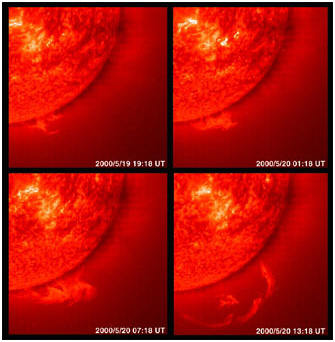

Over the course of 18 hours, a prominence grows from the limb of the Sun and erupts in a coronal mass ejection. A typical CME blasts billions of tons of particles into space at millions of miles per hour. Courtesy of ESA and NASA.

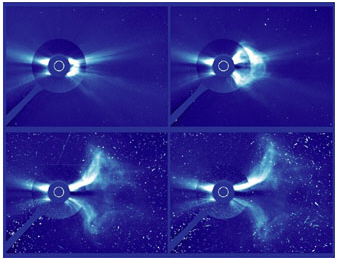

The time-lapse sequence of images from the Large-angle Spectrometric Coronagraph (LASCO) on SOHO depicts a huge bubble of plasma as it is blown away from the Sun. In the last frame (bottom right), solar protons hit the camera, causing “snowy” interference. Courtesy of ESA and NASA.

Comet Hale-Bopp shows off its two tails in 1997— one of dust (white) and one of ions (blue). Comet tails always point away from the Sun, an observation that led to the discovey of the solar wind. Photo by Fred Espenak.

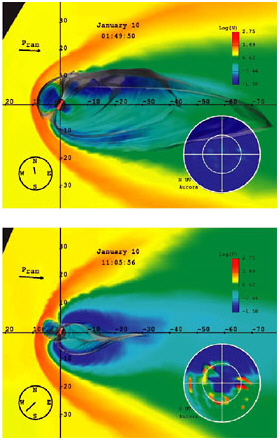

These images come from a computer simulation of the magnetosphere during the magnetic storm of January 1997. Earth lies within the sphere where the two axes meet. The scale in the upper right indicates the density of plasma. The shock wave— known as the bow shock—in front of the Earth is clearly visible, as is the boundary of the magnetosphere. On the lower right is a simulated auroral display in ultraviolet as viewed with the North Pole at the center. The region of magnetic field connected to Earth’s North and South Poles is indicated by the comet-like surface. Note how the magnetosphere shrinks and auroras light up after the arrival of the solar storm. Courtesy of Ramon Lopez.

On October 22, 2001, the Visible Imaging System on NASA’s Polar spacecraft captured both the aurora borealis and the aurora australis (northern and southern lights) in one image of Earth, only the third time such an image has ever been shot. For nearly three centuries, scientists have suspected that auroras in the northern and southern hemispheres were nearly mirror images of each other, but it was not until the Space Age that they were able to confirm that global perspective. Courtesy of VIS/ University of Iowa and NASA.

Astronauts on space shuttle flight STS-39 shot this photo of the aurora australis, or southern lights, in May 1991. Auroras form along the edge of space, where high-energy particles trapped in our planet’s magnetic field slam into the gases of the upper atmosphere. Courtesy of NASA.

Visions such as this auroral serpent preparing to swallow the Moon make it easy to understand how ancient peoples could see monsters, bridges, and ghostly warriors in the northern lights. The photo was shot in November 1998 in Alaska. Courtesy of Dick Hutchinson.

Auroras can take several forms—curtains, rays, bands, arcs—and colors— mostly greens, reds, whites, purples, blues. In this case, the aurora has formed a rare “corona,” a phenomenon where the center of the aurora appears directly overhead, radiating from a center point. Courtesy of Jan Curtis.

A comparison of four images of the Sun in ultraviolet light, taken by SOHO over the course of five years, illustrates how the level of solar activity has increased significantly with the arrival of solar maximum 23. Many more sunspots, solar flares, and coronal mass ejections occur during the solar maximum. Courtesy of European Space Agency and NASA.