Einstein Defiant: Genius Versus Genius in the Quantum Revolution (2004)

Chapter: 17 Exciting and Exacting Times

17

Exciting and Exacting Times

Both Göteborg and Copenhagen lay at Einstein’s back. His train sped him toward Berlin, capital of worthless money. A railroad is usually not the best place for serious work; even Max Wertheimer, who dreamed up Gestalt psychology while riding a train, had to disembark to do the actual experiments. However, work’s dreamy side was unusually fruitful for Einstein, and a train rocking south from Copenhagen was as good a place as any to think about quanta or unified fields. “The kind of work I do,” Einstein once told a friend, “can be done anywhere.”

Most colleagues saw their work as an act of discovery, but Einstein identified more with Beethoven than with Columbus. Scientists of previous centuries, he told one audience, “were for the most part convinced that the basic concepts and laws of physics were not in a logical sense free inventions of the human mind, but rather they were derivable by abstraction—that is by a logical process from experiment.” Presumably, many people in the audience twisted a little in their seats because they still held to that “old” opinion. Einstein continued, “It was the general theory of relativity that showed in a convincing manner the incorrectness of this view.” His most famous theory had been pulled from open sky. The rabbit had not even come from a hat—just out of the clean, blue air.

Speeding around curves, hearing his train’s persistent pahddin-da, pahddin-da, Einstein was poking for still another rabbit. He had liked to base thought experiments about relativity on trains that run at very high speeds along perfectly straight, smooth roadbeds, but the Berlin-bound train’s gentle swaying showed that those examples depended on imaginary trains. Relativity had been limited to uniform motion—movement at a constant speed in a single direction—yet real motion is much more higgledy-piggledy. Naturally, Einstein would have liked to include those irregular motions in his theory, but accelerating motion seems to be absolute. Einstein’s train had left Copenhagen with a sudden move that sent his chair pressing into his back. The passengers all felt that same pressure and knew the train had begun to move. Nobody on the station platform felt an opposite pressure. There seemed to be nothing relative about the train’s sudden accelerating motion. Einstein had been dissatisfied with the limits of his relativity theory, but accelerated motion’s absolute nature seemed to disqualify it from a more general law.

At first Einstein had made no serious attempt to extend his theory. Then in 1907 he noticed still another limit to it. Johannes Stark, who in those days was a great Einstein supporter, asked Einstein for a contribution to a journal that he edited. As Einstein began tinkering with possibilities he realized just how much he had united in his relativity theory—mechanics, electromagnetics, optics, the conservation of matter and energy; in fact every law of physics save one seemed to come under relativity’s wing. That one exception was the most famous of all physical laws—gravity. Einstein’s instinct, of course, was to wonder if he could tug on relativity somewhere to get his law to cover gravity, too. Looking at it quickly—that was another of Einstein’s characteristics; he could see at a glance what others realized only after prolonged study—he determined that relativity was hopeless as far as gravity was concerned. Gravity, through a very odd trait, hides crucial information about falling objects.

As is well known, gravity defies common sense by making everything fall at the same speed. People ordinarily expect a 500-pound anvil to fall faster than a 1-ounce jacks ball. Ancient, medieval, and renaissance physics agreed that heavy things fall faster, but Galileo es-

tablished that everything falls at the same rate. So there is no telling whether a falling object weighs 5 or 5,000 pounds. Relativity’s equations demand some way of calculating the weight or energy of a falling object, but the equality of gravity’s freefall effect hides that data. Ergo, relativity and gravity could not fit together.

Einstein was still working in the Swiss patent office when he wrote the paper for Stark’s journal, and he enjoyed ample time to think of other things. Switzerland’s taxpayers got their money’s worth, however, for he suddenly had what he later described as “the happiest thought of my life.” It was not a great step that resolved a long search, but one of those Detective Columbo moments where Einstein understood what he had to prove. It occurred to him that the explanation for gravity was like the solution he had found for electromagnetics. An electromotive force had seemed like something absolute that was created by a particular action, but it turned out to depend on relative systems. Gravity also seemed absolute, but Einstein suddenly saw that it, too, depends on a kind of relative system, an accelerating one.

In an accelerating system, everything accelerates together and so stays together. That idea suddenly transformed freefall’s equality into an inevitable and obvious point. In uniform systems, say, on the deck of an aircraft carrier, there is no relation between weight and motion. The airplane sitting on the deck of a carrier moves at the same speed as the pilot standing beside it. That fact is hardly mysterious. In an accelerating system, too, everything moves together. As a train speeds up, seats, luggage, and passengers stay together. The same holds for falling objects in gravity. They “fall” together.

When Einstein recognized this unity between acceleration and gravity, he had no ready examples of people working together in free fall. Today we have all seen film of skydiving teams jumping together from an airplane and falling together. The divers do not need to weigh the same. They can even toss objects to each other, just as people on the deck of a moving ship can play catch. Because they stay together without effort and play catch successfully, the skydivers can think of themselves as being at rest, just as the ballplayers on a cruise ship can think of themselves as at rest. (Granted, the divers will get into trouble if they cling to their idea so resolutely that they fail to open their

parachutes.) If one of the skydivers has a radar gun, it will show that the other divers are standing still.

So much of relativity can be observed during a train ride. Clickety-click, on his way between Copenhagen and Berlin, across the German countryside, Einstein could find a wealth of relativistic examples in that simple experience. The pressure surge at startup, the children playing with a ball in one of the compartments, the luggage tag swaying from the suitcase handle, the slender magazine lying still beside a fat passenger, even the light coming in through the window—these ordinary things point toward physics’ deepest secrets. Einstein’s physics is railroad-age physics.

Outside Einstein’s window the train moved through the other Germany, the rural land of towns and villages where Berlin’s modern attitudes had no strength. Barely a quarter of Germany’s people lived in cities of more than 100,000. The other three-quarters were in smaller settlements, half of them even in villages of 2,000 or fewer. They were the places whose young men had been annihilated during the war, communities whose adults had wept when the emperor fled and whose hope had dissolved into an ocean of worthless money. It was because there were so many of these countrified, traditional Germans, that eventually the Nazi party could be voted into power despite its incorrigible weakness among city voters.

Einstein had no interest in or sympathy for that Germany, and it is difficult to imagine him peering through the window at the farmlands in their fertile glory. He was never a great observer, even though science stories classically open with somebody making a puzzling observation: Arthur Compton notices that X-ray frequencies change as they scatter; Darwin notices that the finches of the Galapagos islands are like South American finches, only different. The scientists then, says the story, struggle for the bathtub moment that will explain their observation. With Einstein, it is not clear that he ever noticed an odd phenomenon in his life. His starting point lay in spotting solutions to contradictions between concepts. Next, he would imagine a possible solution to the discrepancy. Finally, either he saw that the proposed solution would not work or he pressed on to the grand step where he saw how to prove that his new solution was correct.

This peculiarity confounds historians who believe that they must look for some observation that set Einstein rolling. In looking at the original theory of relativity, they struggle to establish that Michelson’s and Morley’s experiment or Fizeau’s experiment were the forces that gave Einstein a push. For relativity’s second go-round they like to consider a series of very delicate experiments conducted by a Hungarian baron, Roland Eötvös. The baron had shown that two kinds of masses have identical values. Physicists spoke of inertial mass, which is determined by measuring the acceleration of an object when it is hit by a force. A pool hustler takes a billiard ball’s inertial mass into account when he “kisses” it firmly enough to make it move, but not so hard that it soars over the table’s pocket. A second physical concept is gravitational mass. That’s the amount you measure when you put an object on a scale. Physicists distinguish between gravitational mass and inertial mass because the masses appear in different equations. Eötvös had shown with careful experiment that despite this theoretical distinction, their values are absolutely equal.

Einstein, it seems, knew nothing of the Eötvös experiments, but the findings fit perfectly with what he called the equivalence principle, the idea that gravity is indistinguishable from acceleration. Einstein’s Detective Columbo insight was that the theoretical distinctions between gravitational and inertial masses were heads and tails on the same gold coin. With that idea Einstein abolished the problem of acceleration’s absolute nature. It is true that the passengers aboard a train feel a jolt when the train begins to move, while people on the station platform do not, but the relativity lies in the passenger’s perspective. There is no way to say absolutely whether the back of the chair is accelerating into the spine of the passenger, or if the passenger is pressing into the chair. If we could say that it was absolutely one or the other, then we could know for an absolute fact that acceleration is pushing the chair forward into the traveler or, again as absolute truth, gravity is pulling the traveler backward into the seat. But there is no way to settle the matter absolutely. Acceleration and gravity are dependent versions of the same thing. When a car suddenly stops, are the passengers pushed forward, or is the car seat pushed back? A seat belt works just as well in either case.

One action that did seem absolutely more powerful than others was the movement of Einstein’s imagination once it had grabbed hold of something. While people who are used to thinking of themselves as smart, well above average, and quick-witted are still puzzling to themselves about relative accelerations, Einstein has sped ahead. Relativity in the original theory referred to uniform motion, but now Einstein’s attention focused on fields. The equivalence between acceleration and gravity was his concern now. The equivalence of uniform motions appears in special cases where the rate of acceleration equals zero. All of this:

-

The equivalence of acceleration and gravity

-

The reason everything falls at the same pace

-

The unity of inertial and gravitational mass

-

The solution to the apparent absoluteness of acceleration

-

The shift of theoretical focus from relative motion to relative fields

This whole physics menu was plucked out of thin air while Einstein was daydreaming at his patent-office desk. Mathematicians and novelists routinely turn airy nothing into solid something; physical scientists do it less often.

The experience left Einstein with the optimistic feeling that solutions to mysteries might pop into his head at any movement. Returning from Copenhagen in the summer of 1923, he had been looking 18 years for a clear understanding of radiation, yet, truly, he was not discouraged. The contradiction between wave and particle was like the contradictions he had seen between uniform and accelerating motions, or between mechanical and electromagnetic motions. Light’s appearance as sometimes one thing, sometimes another might be just a dependent phenomenon. Understanding of the critical circumstances might be just around the corner.

![]()

Ideas behave in a way that is the reverse of how photons behave. You can never tell in which direction a photon will go; with ideas, Einstein had learned he could never predict where one would come from. So he stayed alert and kept all views open. It meant reading all the mail, no matter how nutty, and talking freely to any stranger who was bold enough to approach. The Czech novelist Max Brod remembered with amazement “the ease with which Einstein would, in discussion, experimentally change his point of view, at times tentatively adopting the opposite view and regarding the whole problem from a new and totally changed angle.”

He always returned for a fresh look at the quantum. The paper that he sent Stark sketched what an extended theory of relativity would have to prove, but quanta called Einstein back immediately after finishing it and he set relativity aside. Meanwhile his career as an academic physicist finally began to take form. He left the patent office to teach in Bern and later in Zürich. He received his first honorary degree and read his first paper at a science conference. In early spring 1911 he moved with his family to teach at the university in Prague, and during that speedy rise quanta, quanta, quanta held his thoughts.

Part of gravity’s lower priority can be explained by its unprovability. Newton’s theory was already so accurate that its equation had only one known problem. Mercury’s orbit was a little off. All the other planets move as perfectly as God’s own clockwork, but Mercury loses time—very little time: 43 seconds of arc per century. Still, the centuries build up. If Ptolemy had used Newton’s equation 18 centuries earlier, Mercury would have been 12 minutes of arc out of step by 1907 and the crisis would have been very clear. Most physicists, however, were confident that astronomers would eventually find some simple explanation.

Einstein had also imagined an effect that Newton had wondered about but not grasped. Does gravity bend light? Newton thought it might, but nobody worked out a solution until, in 1801, an astronomer named Soldner gave it a stab. He was ignored, however, because Newton’s gravity pulls only things that have mass. Once the wave theory of light took hold, Newton’s query and Soldner’s speculation seemed impossible. Waves do not have mass. Einstein, however, con-

cluded that light does bend when it enters a gravitational field. As usual with relativity, the prediction is visualizable in terms of the train that Einstein rode between Copenhagen and Berlin. Imagine that while the train sped through the night, a shaft of light passed through the compartment window to flash briefly against the compartment’s far wall. The light is no part of the train’s relative system, so it will not move with the train. During the time that the light travels from the compartment window to the compartment’s wall, the train moves forward a little bit. From Einstein’s perspective inside the train, the light beam will not travel in a straight line perfectly parallel to the facing compartment wall. It will bend; the light beam will be a little closer to the back of the train when it hits the wall than when it entered the window. Normally we would say that the light does not really bend. The train has merely moved forward while the light was traveling straight. But that rebuttal is common sense, not relativity theory. From passenger Einstein’s relative perspective, he is sitting still. The train has not moved forward, the light’s path has just bent.

Well, asks the common-sense thinker, if the train is not moving, why has the light path curved?

Easy, judges Einstein, it bent because of the train’s gravitational field.

The train’s gravitational field, wonders the common sense thinker. Does the train have a gravitational field?

Sure. Newton showed that anything that has mass has gravity.

So, realized Einstein, light passing through any moving system will appear to bend, and since gravity is equivalent to accelerated motion, light will bend in a gravitational system as well.

This is where many smart people balk and refuse to follow Einstein. Wait, we wonder, can we be so sure that this light bending will work in gravity just because it works for motion? Maybe there are prudent reasons for doubting and hesitating, but Einstein did not doubt, did not hesitate. Like a rock climber hanging over emptiness, he saw the equivalence principle as his only fingerhold, and he was determined to pull himself up as completely and robustly as he could. His theory of gravity would, therefore, assume that light did bend. The trouble was that this bending is almost impossible to detect. We can all

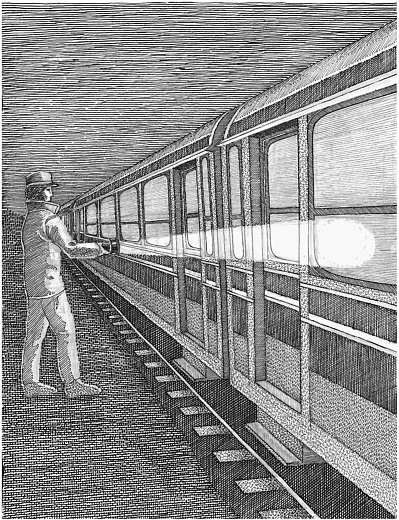

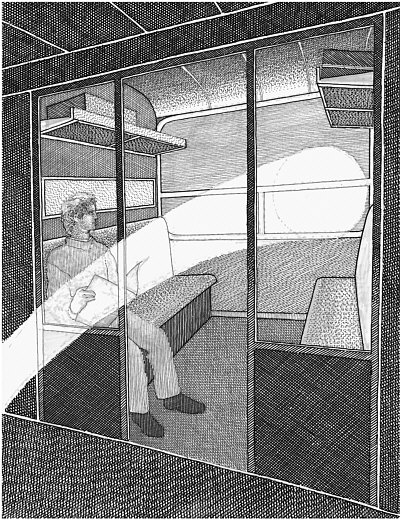

LIGHT BEAM RELATIVE TO ITS SOURCE: Newton’s first law of motion holds that an object in motion travels in a straight line unless acted upon by a force. This law can be demonstrated with a flashlight. An observer holding a flashlight sees the light travel in a straight line, even when it enters the compartment of a moving train. Drawing by Pascal Jalabert.

LIGHT BEAM RELATIVE TO A RAILROAD COMPARTMENT: A passenger in a railroad compartment sees light from a flashlight bend slightly as it travels from the window to the wall. From the passenger’s perspective, the train is standing still so gravity must have forced the light path out of its straight line. In general relativity, not just time and motion are relative, but also the shape of a line. Drawing by Pascal Jalabert.

agree that in principle light bends as it travels from train window to train wall, but in practice the bend is beyond all discovering. It takes about a hundredth of a nanosecond for the light to travel from window to wall. During that instant a train traveling at 60 miles an hour moves only about three-hundred-thousandths of a millimeter. Testing for such tiny effects looked hopeless.

However, while he was teaching in Prague, Einstein thought of a way to test for these absurdly small distortions. Light passing right by the sun will be bent by the sun’s gravity, and by the time the light travels another 93 million miles to reach the earth, even very slight changes will be detectable. Normally, of course, the sun blinds observers to any light passing by, but stars become visible during a solar eclipse when the moon blocks out the sunlight. Einstein even calculated how far starlight should be bent. Assuming that Newton’s value for the force of gravity was correct, he found that starlight grazing the sun’s border would bend 0.83 seconds of arc. That looked promising, and Einstein took a long break from his quantum efforts.

![]()

Typically, Einstein had zigged while everybody else was zagging. He had proselytized for years, trying to enlist the interest of other physicists in the quantum. In autumn 1911, those efforts finally inspired the first Solvay Conference, which moved the quantum onto physics’ center stage. Einstein joined Solvay’s party and was delighted by the event, but he had switched his thoughts to a revised relativity and he continued to act as a lone mind thinking his way through a maze.

The task, as Einstein saw it, was to develop a theory of gravity that led logically to the equivalence principle, so the theory would have to predict bending light. Newton’s theory already worked amazingly well, so Einstein’s new theory would have to give Newton’s results wherever the old equation worked. The theory would be an extension of Einstein’s own theory of relativity, so it would also have to match Einstein’s results for cases of uniform motion. In other words, he needed a theory that managed to swallow the two greatest theories

in physics; Einstein, a true jumping horse, never shied from an impossible leap.

He did worry, however, that relativity seemed to be coming apart before his eyes. Mathematical theories stretch over the real world rather like fitted sheets over a too-large mattress. When you fit one corner, another pops open. Einstein had begun by looking for a way to cover mechanical motion and electromagnetic motion at the same time. He fitted his theory to cover them, but accelerated motion and gravity were still exposed. Then he saw a way to cover them, but, in response, parts of relativity’s corner came open. The trouble lay with his axiom that the speed of light in a vacuum never changes.

Can anything in the real world remain constant? Doesn’t much of the pleasure of train travel come from the way passengers can sense all those tiny adjustments and shifts as the train speeds along the rails. It is never as smooth as an escalator’s climb. You feel the rhythm of the joints in the rail. The gentle swaying seems to hug you; it provides an almost human reassurance that you are in strong, capable hands. Everything rocks just a bit. Even the luggage tag hanging down from the suitcase handle sways slightly to its own tune as the train carries it along. Isn’t nature full of these fluxes? How can anything, even something as grand as light, move along at only one constant speed? Mustn’t that be a dream?

Einstein feared it might be. He realized that when light seems to bend it should change speeds while rounding a curve. Horse racing fans can see that the inside track is much shorter than the outside. As thoroughbreds dash along a straight-away the outside runners keep pace with those on the inside, but going into the curve the outside horses fall behind. The curve does not slow down the runners, but the further outside a champion runs, the further it must travel. The inside has the advantage. It works that way for horses and motorcycles, and it should for light, too. Yet experiments have shown that light on the outside of a curve keeps perfect pace with the inside light. To do that, the light on the outside has to be going faster than light on the inside curve. Doesn’t that contradict the rule that the speed of light never varies?

By then, Einstein had had plenty of practice at overcoming this

kind of challenge; the solution lay in time’s relativity. Light rays on the outside curve could keep pace with the inside rays if the inside time went slower than the outside time. To test whether it is the speed of light or the march of time that changes, Einstein proposed to use light’s built-in clock, its frequency. Electromagnetic radiation has a specific frequency of some number of cycles per second. That is what the υ in the photon’s hυ represents. If the speed of light changes, it will have no effect on the frequency, but if the time were to change so that the light’s time was no longer synchronized with our own, the color of the light would seem to change. Suppose time changes for something with a frequency of 100 cycles per second. If time slows by half, an observer will count only 50 cycles per second. We can then see with our eyes that the light’s clock is running slow.

Light frequencies are visible from a range of 750 trillion cycles per second (the violet end of the rainbow) to 430 trillion (the red end). With so many up and down motions per second, a light wave serves as a wonderfully delicate clock. Even slowing time by a trillionth of a second (a picosecond) will produce physical results. If time slows very slightly, light of 500 trillion cycles per second might appear to have only 485 trillion cycles. This is much too subtle a difference for the eye to detect, but perhaps a very precise measuring device could discover the change. If Einstein were right and time does slow down, an outside observer would see light’s frequency decrease. Because red has visible light’s lowest frequency, this lowering of light’s frequency is known as a “red shift.” The light does not really become red, but its frequencies move toward the rainbow’s red side.

This new notion of time slowing marked a change from Einstein’s original idea of relative time. The 1905 theory saw shifting time as a property of the whole relative system. Time flows at the same pace for everything at rest on an aircraft carrier. It might be flowing slightly differently for people on a lighthouse, but those people are in a different relative system. In Einstein’s revised theory, time could flow differently for things in the same relative system. They just had to be in different parts of a gravitational field. Time could be ticking at one pace at the top of a building and another pace at the bottom. Time was no longer like a platform that keeps everything together. Instead, pic-

ture a river that carries everything in one direction, but where a complex pattern of eddies and winds gradually separate floating objects that started out side by side. A drift in any direction can bring enduring changes in relative position. Time, the universal experience, was becoming a wobbly measuring stick.

The radical heart of Einstein’s new thinking about time is caught in the old metaphor, based on Newton’s laws, that God was a great watchmaker who set the universe in motion and then let it flow with time’s own perfect regularity. Hidden somewhere in that image is the notion of time being as absolute as God Almighty. Now Einstein was saying, no, time is not God, is not absolute. It changes with motion; it changes with gravity.

![]()

Einstein traveling from Copenhagen to Berlin found himself like Alice down the rabbit hole. The world that passed his window did not match the one imagined by his fellow passengers. For them the train was moving, the countryside stood still, and there were no two ways about it. Not for Einstein. “Eat me,” said a cookie, and Einstein had eaten, discovering as he did so that physics worked just as well if you said the train was at rest and the countryside sped by. Time, too, for passengers outside the rabbit hole, was easy. It flowed at a steady tick-tock, as measured by their pocket watches. “Drink me,” said a vial and Einstein drank, concluding thereafter that as he swayed with the railway car he was bobbing and bouncing through a world where time’s pace rose and fell like a canoe struck by the wake of a passing tanker. That little swaying luggage tag was bobbing in a time all its own.

Time’s wobbly nature did let Einstein tuck one corner of his theory in place, but immediately another corner popped open. His beloved relativity principle began to look untenable. That principle held that the same physical laws are true for every observer. The laws of physics were the same for Einstein on the train and for people in the countryside farms. When Einstein boarded a railway ferry to cross from Denmark’s islands to the European mainland, the physical laws

on the ferry matched the laws on the train and in the farmhouses. By this principle, Einstein meant that if you performed experiments in those separate locations you would discover the same laws. If you were Einstein, you could discover relativity anywhere. Thus, an Einstein aboard a railway ferry could perform an experiment, do a calculation, and say, “You know, that phenomenon looks different from the train.” Thanks to the math, the experimenter could tell everybody aboard the ferry exactly how things looked from the train. But with wobbly time these calculations were not working. You could not be sure what the other people saw.

Even patient Einstein appears to have grown frustrated with the way one corner or another of this theory kept coming undone. We can guess at this upset partly because it would rattle anybody, although Einstein’s patience and optimism made him unlike just anybody. A more telling sign of his deepening frustration was the old flag that seems to have been impressed on his psyche, he began a passionate love affair. During this period, he visited Berlin on an unsuccessful job hunt. Wherever Einstein went, a woman or two was likely to catch his eye. Usually these incidents implied no more emotion than a sailor’s tryst in the latest port of call, but physics had grown unsatisfactory and, in Berlin, Einstein began an affair with his recently divorced cousin. Stymied by gravity, he began writing indiscreetly to Elsa.

April 30, 1912:

My dear Elsa, No sooner had I left you than the thought started to weigh on me that it would be impossible to write to you since you are so closely watched. How happy I was then today when I saw from your letter that you found a way that will allow us to stay in touch with each other. How dear of you not to be too proud to communicate with me in such a way. I can’t even begin to tell you how fond I have become of you during these few days…. In your amiable way you are making fun of me, but this does not make me like you even one iota less. I am in seventh heaven when I think of our trip to Wannsee.

In Prague, a colleague and musical friend named George Pick told Einstein to expand his mathematical horizons; he needed a new language more than he needed a new experiment or even a new idea.

Einstein, however, was not that kind of poet. Shakespeare was liable to reshape English every time he dipped his quill. Proust, to express his psychology of time, developed a new style of French. Newton, when he found the existing mathematics was insufficient for analyzing motion, invented differential calculus. Einstein called that deed, “perhaps the greatest intellectual stride that it has ever been granted to any man to make.” Einstein’s working language was also mathematics, but in this area he was no Newton. Although Einstein was surely the most original physicist ever, his mathematical talents lay simply in applying known methods to his physics.

May 7, 1912:

I suffer very much because I’m not allowed to love truly, to love a woman who I can only look at. I suffer even more than you, because you suffer only for what you do not have.

Einstein had outrun Euclid’s geometry. During his trip to Japan, Einstein told an audience, “Describing the physical laws without reference to geometry is similar to describing our thought without words. We need words in order to express ourselves.” But sometimes we need new words. There were other geometries besides Euclid’s, although most physicists would have said that switching to some other geometry was absurd. Euclid’s was the true geometry; anything else was a mathematician’s game. But Einstein had been much impressed by Poincaré’s argument that Euclid’s geometry is no more the true geometry than meters and kilograms comprise the “true” system of measurements. Geometries are tools for describing reality.

Johannes Kepler once, as he struggled with the problem of defining Mars’s orbit, wrote an equation that expressed changes in the planet’s position. Today any mathematician or astronomer would look at that equation and know immediately that it described an ellipse, but in Kepler’s day geometry had not yet been combined with algebra; he had no way of knowing what his equation meant. Einstein in Prague was stifled that same way. His physics demanded more geometry than he had.

In midsummer 1912, he left Prague to teach again in Zürich. As

soon as he was back in Switzerland he looked up his old classmate and friend, Marcel Grossman, who had become a mathematics professor. Einstein poured out his troubles just as, eight years earlier, he had revealed all his frustrations to Besso. “Grossman, you must help me or I will go crazy,” Einstein begged.

Grossman did come to the rescue, acquainting his friend with a geometry developed 60 years earlier at Göttingen by Bernhard Riemann. Perhaps the system’s most notable feature is that it has no parallel lines. Space in Riemann’s system is often said to be “curved,” but that is a Euclidean prejudice, like saying Arabic books run “backward.” Riemann’s geometry has straight lines, and Einstein’s physics still accepts Newton’s axiom that an object in motion will continue to move in a straight line. It is just that straight lines in the Riemann system do not look straight from Euclid’s perspective. In Riemann’s system, “bending” can turn out to be a Euclidean illusion. Light passing through an accelerating or gravitational system might appear to bend in Euclid’s space, but not in Riemann’s. Einstein did not yet understand how that could be physically real, but he knew that if he could prove it, he would have solved his case.

March 23, 1913:

What wouldn’t I give to be able to spend a few days with you, but without … my cross! Will you be away all of (August until the beginning of October)? If not, then I would like to come for a short visit. At that time my colleagues will not be there, so we would be undisturbed.

To understand how a straight line can seem crooked, use a ruler and a colored felt pen to draw a line on a flat sheet of transparent plastic wrap. Next, crumple the wrap into a ball. That’s the whole of the experiment. Using a ruler to draw a line assures that the resulting mark meets the classic definition of a straight line; it is the shortest distance between two points. Crumpling the wrap does not stop the line from being the shortest route between any two points it crosses; however, crumpling the wrap did change the line’s appearance. Viewed from outside, the line looks crooked, yet a creature living on the wrap’s surface would find that the line still marked the shortest path to all its

points. So is the line really crooked or straight? There is no absolute answer.

Einstein’s abandonment of Euclid changed the problem facing physics. Newton looked at the sky with Greek eyes and said the planets do not move in a straight line. There must be some force pulling or pushing the planet out of straight motion. With a little detective work, Newton concluded the force was a pull. This pull was mysterious, acting instantly at a distance, but the facts of elliptical orbits were plain. So Newton’s gravitational equation tells how to calculate gravity’s pull.

Einstein argued that the bending of lines was relative. From the perspective of anything traveling along the line, it goes straight. A light beam entering a moving train compartment goes straight, from the perspective of the light beam, but from the passenger’s view it bends. This relativistic conception of paths demanded a new way of describing how the wrap crumpled, so to speak—that is, what the space looks like to a particular observer. The equation that Einstein wanted would have to describe the apparent curving and crumpling of space.

![]()

Surely there were tourists, perhaps many of them, aboard the train from Copenhagen. How exciting for them to discover a bonus, a world-famous passenger having coffee and a smoke in the dining car. With the mark turned worthless, vacationers could visit Germany and use their real money to buy anything they wished. The Germans saw them and resented the invasion. They had not been warned about how humiliating it is to lose a war.

Tullio Levi-Civita and Gregorio Ricci, two Italian mathematicians, had developed a calculus based on Riemann’s geometry. Grossman began to study and teach Einstein the system. Einstein, of course, was an able pupil and moved swiftly to geometry’s front-line, where he began chopping himself a path. In 1913, Einstein and Grossman published a paper together in which they offered their new equation, but Einstein was unsatisfied. The proposed new law appeared to ignore the requirement that a single set of circumstances must al-

ways lead to the same result. Without that regularity, causality disappears from science.

Newton’s gravitational equation was the perfect example of mathematical causality. Insert the same numbers and you always get the same result. But Einstein’s equation seemed to allow for an infinite variety of outcomes, all based on the same gravitational circumstances. That variability did not sound right, so Einstein kept working.

February 1914:

Dear Else, Don’t be angry with me for my being such a poor letter writer. This does not mean that I love you any less. I cannot find the time to write because I am occupied with truly great things. Day and night I rack my brain in an effort to penetrate more deeply into the things that I gradually discovered in the past two years and that represent an unprecedented advance in the fundamental problems of physics.

He moved from Zürich to Berlin but continued rethinking gravity. The World War began; he kept working. The work would have been impossibly lonely if Einstein had not been so enchanted by his own questions. A pacifist in a wartime capital, he was hated by many. Many others resented the way he silently laughed at their anguish over the world’s distaste for German grandeur. A theorist trying to replace science’s most successful theory, he found little sympathy for rethinking Newton. Yet, as 1915 began he wrote a friend, “I firmly believe that the road taken is in principle the correct one and that [people] later will wonder about the great resistance the idea of general relativity is now encountering.” Einstein’s colleagues repeatedly saw his efforts as mere windmill jousting. Then, when he bagged another giant, they could only gape in amazement.

Some of Einstein’s optimistic tone might have been bluff, yet there is something fantastic about even bluff optimism in January 1915. That winter was one of the most dismaying in world history. In the preceding four months, the western front had formed. A trench line had been dug from the English Channel to the Swiss border and each side was besieging the other. The war was going to persist indefinitely. In Munich, Thomas Mann had been working on The Magic Mountain since July, 1913, but by early 1915 he found that the war was too

distracting and he set his novel aside for the duration. But Einstein was able to set mass slaughter aside, just as he put love aside, to concentrate on his physics.

![]()

In midsummer 1915, Einstein underwent a crisis of faith. He realized that his previous papers on gravity formed “a chain of false steps” and that he was clinging to untenable ideas. At first this recognition was as frightening as finding oneself lost in a wood, but he screwed up his courage and found the strength to take yet another grand step. He had been insisting that relative systems are as real as the deck of a ship, or the platform of a lighthouse, or some such concrete place. Being real, relative systems are limited in number and meaning. Truly, he realized, they are merely arbitrary abstractions, something theory imposes on the cosmos in order to provide a reference point. You can make your reference point the bridge of a ship or a spot 10 feet above the ship. You can align your reference coordinates so that they run through the center of the earth, or tilt them to run some other way. Whatever you choose, it is just a reference point and not part of nature itself.

Einstein’s abandonment of real, relative systems might have been his most difficult feat of imaginative resourcefulness. Relative systems had been crucial to his original theory; now he threw their reality aside. It was the kind of back flip that Lorentz had missed when he held to the reality of absolute time and thus lost the meaning of his own equations. And, as happened 10 years earlier when Einstein took his great step toward relativity, he followed the rejection of real reference points with a month of frenzied work, tracing the mathematics and logic of his new understanding. In the two years since he had written the paper with Grossman, Einstein had tried many new equations and calculations. Now he tossed all that aside and went back to the mathematics of that 1913 paper. “In two weeks,” Einstein recalled, “the correct equations appeared in front of me!”

When the outpouring was over, Einstein wrote to Sommerfeld, “During the last month I experienced one of the most exciting and exacting times of my life.” Exciting it was, as clarity and proof spilled

over his notebooks. The problem of an infinite number of solutions to the same set of circumstances simply evaporated. There were an infinite number of ways to define the reference points, but each definition led to a single solution. A predictable outcome—causality—had returned to his physics.

Factual support for the theory appeared as well. The old equations that had proven so useful in the original theory of relativity could be derived from the new equations. They served in a special case—instances of uniform motion through Euclidean space—and Einstein began to call his first theory “special relativity.” Then he was able to show that in all the cases where Newton’s gravitational equation worked properly, his own results were so similar as to be identical.

Next he turned his attention to the case where Newton’s equation did not work so perfectly, Mercury. Solving his equation for the orbit of Mercury was demanding work, and when the solution matched reality Einstein felt palpitations of the heart.

“For a few days,” he told Ehrenfest, “I was beside myself with joyous excitement.”

“Something actually snapped,” he told another friend. Ideas pulled from his head had matched the data gathered by sweating astronomers winking through telescopes.

If at that moment reporters from the world press had appeared at his doorway and Einstein had become at once the world’s most famous scientist, he might have understood why he was so applauded. But he received no such cheers. Every Saturday for four weeks in November 1915, he rose from his seat in the Prussian Academy to report his progress. On November 4, he described his break with absolute coordinates. November 11, more mathematics. November 18, still more mathematics, demonstrating now that the equations settled the problem of Mercury’s orbit and that he calculated that the bending of light passing by the sun would be twice the size of the prediction he had based on Newton’s gravitational value. November 25, he presented his final equation and reported that “any physical theory that obeys special relativity can be incorporated into the general theory of relativity.” His work on relativity was done.

A few days later he told Sommerfeld that the final equation he

presented was almost identical to one that he and Grossman had considered two years earlier but rejected. It had contradicted the conservation of energy. Einstein had changed the equation just a little bit, such a little bit that it hardly seemed to matter except that it now conserved all the energy. And it was just that little bit that led to the correct calculation of Mercury’s orbit and to the revised figure for the bending of starlight passing the sun.

Sommerfeld responded that he was astonished to hear Einstein claim to have solved gravity. “You will be convinced once you have studied it,” Einstein replied, “Therefore I am not going to defend it with a single word.”

But unadulterated happiness never lasted long in Einstein’s heart. He soon noticed that a corner of his mattress that had seemed tucked tightly had again become visible. Physics suddenly had two fields—one gravitational, one electrical—sitting right on top of one another with no connection between them. It was as frustrating for Einstein as mind-body dualism is for more ordinary thinkers. There must be a way, he was sure, for one law to account for both of those fields. Almost eight full years later, as Einstein’s train returned him to Berlin, he was still looking for that way.