Summary

Growing worldwide energy demand, high commodity prices, high economic growth in developing countries, and growing scientific evidence that atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) is an important contributor to global climate change make it urgent to increase energy supply and reduce worldwide greenhouse gas emissions at the same time. Achieving the first goal will require increasingly efficient energy production and use and expanded development of alternative sources of energy supplies that have low greenhouse gas emissions. In the United States today, the transportation sector relies almost exclusively on oil. Although domestic energy sources can supply all U.S. electricity needs, the United States is unable by itself to satisfy transportation sector and petrochemical industry demand for oil and so currently imports about 56 percent of the petroleum used in the United States. Moreover, volatile crude-oil prices and recent tightening of global supplies relative to demand, combined with fears that oil production will peak in the next 10–20 years, have aggravated concerns over oil dependence. The second goal is reduction of greenhouse gas emissions from the transportation sector, which accounts for one-third of the total emissions in the United States. Those two objectives have motivated the search for new vehicle power trains and alternative domestic sources of liquid fuels that can substantially lower greenhouse gas emissions.

Coal and biomass are abundant in the United States and can be converted to liquid fuels that can be combusted in existing and future vehicles with internal-combustion and hybrid engines. Their abundance makes them attractive candidates to provide non-oil-based liquid fuels for the U.S. transportation system. However, there are important questions about their economic viability, carbon

impact, and technology status. Coal liquefaction is a potentially important source of alternative liquid transportation fuels, but the technology is capital-intensive. More important, fuel from liquefaction produces about twice the amount of greenhouse gas emissions on a life-cycle basis1 as does petroleum-based gasoline if the process CO2 is vented to the atmosphere. Capture of the process CO2 and its geologic storage in the subsurface, often referred to as carbon capture and storage (CCS), will be required for producing coal-based liquid fuels in a carbon-constrained world. Thus, the viability, costs, and safety of lifetime geologic CO2 storage could be barriers to commercialization.

Biomass is a renewable resource and, if properly produced and converted, can yield biofuels that have lower greenhouse gas emissions than do petroleum-based gasoline and diesel. Biomass production on already-cleared fertile land might compete with food, feed, and fiber production. If ecosystems are cleared directly or indirectly to produce biomass for biofuels, the resulting release of greenhouse gases from the cleared lands could negate for decades to centuries any greenhouse gas benefits of using biofuels. Thus, there are questions about how much biomass could be used for fuel without competing with food, feed, and fiber production to an important degree and without having adverse environmental effects.

STUDY SCOPE AND APPROACH

As part of its America’s Energy Future (AEF) study (see Appendix A), the National Research Council appointed the 16-member Panel on Alternative Liquid Transportation Fuels to assess the potential for using coal and biomass to produce liquid fuels in the United States; provide thorough and consistent analyses of technologies for the production of alternative liquid transportation fuels; and prepare a report addressing the potential for use of coal and biomass to substantially reduce

U.S. dependence on conventional crude oil and also reduce greenhouse gas emissions in the transportation sector. The full statement of task is given in Appendix B. Although the report is the product of this independent panel, the results it presents will contribute to the larger AEF study mentioned in Appendix A.

The panel focused on technologies for converting biomass and coal to alternative liquid fuels that will be commercially deployable by 2020. Technologies that will be deployable after 2020 were also evaluated, but in less depth because they are associated with greater uncertainty than are the more developed technologies. For the purpose of this study, commercially deployable technologies are ones that have been scaled up from research and development to pilot-plant scale and then to several commercial-size demonstrations. Thus, the capital and operating costs of plants using commercially deployable technologies have been optimized so that the technologies can compete with other options. Commercial deployment of a technology—the rate at which it penetrates the market—depends on market forces, capital and human resource availability, competitive technologies, public policy, and other factors.

Because the choices for alternative liquid fuels are so many and so complex, the panel was unable to assess every potential biomass or conversion technology in the time available for this study. Instead, it focused on biomass supply and technologies that could potentially be commercially deployable over the next 15 years, be cost-competitive with petroleum fuels, and result in substantial reductions in U.S. oil consumption and greenhouse gas emissions. Other potential alternative fuels are reviewed at the end of the report (Chapter 9).

This study was initiated at a time (November 2007) when the prices of fossil fuels and other raw materials and the capital costs for infrastructure were rising rapidly. As the study progressed, those prices reached a peak (for example, the crude-oil price reached $147/bbl on July 11, 2008) and then began to fall steeply. Currently, there is continuing uncertainty about some of the factors that will directly influence the rate of deployment of technologies and the costs of new transportation-fuel supplies. The panel also recognized early in its deliberations the extent of the considerable debate reported on coal and biomass conversion technologies and biomass feedstock potential.

To decrease the uncertainty in its analysis and to ensure consistency among models used for comparison, the panel—with input from the Princeton Environmental Institute, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Purdue University, the University of Minnesota, Iowa State University, and the Renewable Energy Assessment Project team of the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Agricultural Research

Service—developed methods for estimating the costs and greenhouse gas impacts of supplying biomass, biochemical conversion, thermochemical conversion, and the potential quantity of fuel supply. Because of pervasive levels of uncertainty, however, the energy supply and cost estimates provided in this report should be considered as important first-step assessments rather than forecasts. The panel’s estimates of the total costs of fuel products—including the feedstock, technical, engineering, construction, and production costs—were derived on a consistent basis and on the basis of a single set of conditions.

U.S. public policies related to energy have been introduced over the years. The oil crises of the 1970s sparked a number of energy-policy changes at the federal, state, and local levels. Price controls and rationing were instituted nationally, along with a reduced speed limit, to save gasoline. The Energy Policy and Conservation Act of 1975 created the Strategic Petroleum Reserve and mandated the doubling of fuel efficiency for automobiles from 13 to 27.5 miles/gal according to the corporate average fuel economy (CAFE) standards. Alternative fuels have been promoted in several other government incentives and mandates, including the Synthetic Liquid Fuels Act of 1944, the Energy Security Act of 1980 (which contained the U.S. Synthetic Fuels Corporation Act), the Alternative Motor Fuels Act of 1988, the Energy Policy Act of 1992, the Energy Policy Act of 2005, and the recent Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007 (which aims to increase the use of renewable fuels to at least 36 billion gallons by 2022 and set a new CAFE standard of 35 miles/gal by 2020). In addition, the American Jobs Creation Act of 2004 provided a tax credit of $0.51/gal of ethanol blended to companies that blend gasoline and a tax credit of $0.50–$1.00/gal of biodiesel to biodiesel producers.

Even though many public policies have addressed transportation-energy supply and use over the last 60 years and large amounts of public money have been spent, the use of alternative transportation fuels in the U.S. market today is still proportionately small. Many factors are involved in this low market penetration, such as generally low oil prices, but the fact that many of the policies have not been durable and sustainable has played an important role.

In its report, the panel identifies what it judged to be “aggressive but achievable” deployment opportunities for alternative fuels. Over the course of its study, it became clear to the panel that given the costs of alternative fuels and the volatility of fuel prices, significant deployment of alternative fuels in the market will probably require some realignment of public policies and regulations and the

implementation of other incentives, such as substantial investment by both the public and the private sectors.

This summary includes some of the panel’s key findings and recommendations; details of the panel’s assessment and additional findings and recommendations are presented in subsequent chapters of the report. Quantities are expressed in standard units that are commonly used in the United States, except that greenhouse gas emissions are expressed in tonnes of CO2 equivalent (CO2 eq), the common unit used by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

TECHNICAL READINESS FOR 2020 DEPLOYMENT

Biomass Supply

Responsible development of feedstocks for biofuels and expansion of biofuel use in the transportation sector must be socially, economically, and environmentally sustainable. The social, economic, and environmental effects of producing and using domestic biofuels have been mixed. In 2007, the United States consumed about 6.8 billion gallons of ethanol, mostly made from corn grain, and 491 million gallons of biodiesel, mostly made from soybean. The combined total of those two biofuels is less than about 3 percent of the fuels consumed for U.S. transportation. Diverting corn, soybean, or other food crops to biofuel production induces competition among food, feed, and fuel. Producing corn-grain ethanol and soybean biodiesel involves substantial use of fossil-fuel and other resources, and the improvements in greenhouse gas emissions compared with emissions associated with petroleum-based gasoline are small at best. Thus, the panel judges that corn-grain ethanol and soybean biodiesel are intermediate fuels in the transition from oil to cellulosic biofuels or other biomass-based liquid hydrocarbon transportation fuels, such as biobutanol and algal biofuels. In contrast, liquid biofuels made from lignocellulosic biomass can offer major improvements in greenhouse gas emissions relative to those from petroleum-based fuels if the biomass feedstock is a residual product of some forestry and farming operations or if it is grown on marginal lands that are not used for food and feed production.

Lignocellulosic feedstocks can be derived from both forestry and farming operations, including some production on marginal lands where commodity production often results in increased environmental problems because of erosion, runoff, and nutrient leaching. Therefore, the panel focused on the lignocellulosic

resources available for biofuel production and assessed the costs of different biomass feedstocks delivered to a biorefinery for conversion. It considered societal needs, using recent analyses that have examined tradeoffs between land use for biofuel production and land use for food, feed, fiber, and ecosystem services. Corn stover, wheat and seed-grass straws, hay crops, dedicated perennial grass crops, woody biomass, wastepaper and paperboard, and municipal solid waste are the biofuel feedstocks considered in this report.

The panel estimated the amount of cellulosic biomass that could be produced sustainably in the United States and result in fuels with substantially lower greenhouse gas emissions than petroleum-based fuels. For the purpose of this study, the panel considers biomass to be produced in a sustainable manner (1) if croplands would not be diverted for biofuels and land therefore would not be cleared else-where to grow crops displaced by fuel crops and (2) if growing and harvesting of cellulosic biomass would incur minimal or even reduce adverse environmental effects such as erosion, excessive water use, and nutrient runoff. The panel estimated that about 400 million dry tons per year of biomass can potentially be made available for production of liquid transportation fuels with the technologies and management practices of 2008 (Table S.1). The cellulosic-biomass supply could increase to about 550 million dry tons per year by 2020. Key assumptions in the analysis are that 18 million acres of land currently enrolled in the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) would be used to grow perennial grasses or other perennial crops for biofuel production and that the acreage would increase to 24 million by 2020 as knowledge increases. Other key assumptions are that harvesting methods would be developed for efficient collection of forestry or agricultural residues; that improved management practices and harvesting technology would increase agricultural crop yield; that yield increases could continue at the historical rates seen for corn, wheat, and hay; and that all the cellulosic biomass estimated to be available for energy production would be used for liquid fuels (this leads to an estimate of the potential amount of fuels produced).

The panel presented a scenario in which 550 million dry tons of cellulosic feedstock could be harvested or produced sustainably in 2020. That estimate is not a prediction of what would be available for fuel production in 2020. The supply of biomass could exceed the panel’s estimate if croplands are used more efficiently or if genetic improvement of dedicated fuel crops exceeds the panel’s estimate. In contrast, the panel’s estimate could be lower if producers decide not to harvest agricultural residues or not to grow dedicated fuel crops on their CRP land.

TABLE S.1 Estimated Amount of Lignocellulosic Feedstock That Could Be Produced for Biofuel in 2008 with Technologies Available in 2008 and 2020

|

Feedstock Type |

Millions of Tons |

|

|

With Technologies Available in 2008 |

With Technologies Available by 2020 |

|

|

Corn stover |

76 |

112 |

|

Wheat and grass straw |

15 |

18 |

|

Hay |

15 |

18 |

|

Dedicated fuel crops |

104a |

164 |

|

Woody biomass |

110 |

124 |

|

Animal manure |

6 |

12 |

|

Municipal solid waste |

90 |

100 |

|

Total |

416 |

548 |

|

aCRP land has not been used for dedicated fuel-crop production as of 2008. The panel assumed that two-thirds of the potentially suitable CRP land would be used for dedicated fuel production as an illustration. |

||

The panel also estimated the costs of biomass delivered to a conversion plant (Table S.2). In that analysis, the price that the farmer or supplier would be willing to accept was assumed to include (1) land rental cost and other forgone net returns from not selling or not using the cellulosic material for feed or bedding and (2) all other costs incurred in sustainably producing, harvesting, and storing the biomass and transporting it to the processing plant. The willingness-to-accept price or feedstock price is the long-run equilibrium price that would induce suppliers to deliver biomass to the processing plant. Because an established market for cellulosic biomass does not exist, the panel’s analysis relied on published estimates. However, the panel’s estimates are higher than those in published reports because transportation and land rental costs are included.

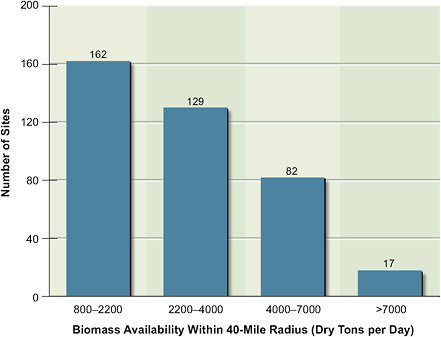

The geographic distribution of biomass supply is also an important factor in the potential for development of a biofuels industry in the United States. The panel estimated the quantities of biomass that could, for example, be available within a 40-mile radius (which is about a 50-mile driving distance) of a given fuel-conversion plant in the United States (Figure S.1). An estimated 290 sites could supply 1,500–10,000 tons of biomass per day (0.5 million–2.4 million dry tons per year) to conversion plants within a 40-mile radius. The wide variation in the geographic distribution of the biomass potentially available for processing at plants will affect processing-plant size and is a factor in the potential to optimize

TABLE S.2 Biomass Suppliers’ Willingness-to-Accept Prices in 2007 Dollars for 1 Dry Ton of Delivered Cellulosic Material

|

Biomass |

Willingness-to-Accept Price (dollars per ton) |

|

|

Estimated in 2008 |

Projected in 2020 |

|

|

Corn stover |

110 |

86 |

|

Switchgrass |

151 |

118 |

|

Miscanthus |

123 |

101 |

|

Prairie grasses |

127 |

101 |

|

Woody biomass |

85 |

72 |

|

Wheat straw |

70 |

55 |

FIGURE S.1 The number of sites in the United States with a potential to supply the indicated daily amounts of biomass within a 40-mile radius of each site.

each conversion plant to decrease costs and maximize environmental benefits and supply in a given region. For example, increasing the distance of delivery could result in larger conversion plants with economies of scale that could lower fuel production costs.

To attain the panel’s projected sustainable biomass supply, incentives would have to be provided to farmers and developers to use a systems approach for comprehensively addressing biofuel feedstock production; soil, water, and air quality; carbon sequestration; wildlife habitat; and rural development. The incentives would encourage farmers, foresters, biomass aggregators, and those operating biorefineries to work together to enhance technology development and ensure that the best management practices were used for different combinations of landscape and potential feedstock.

Finding S.1 (see Finding 2.1 in Chapter 2)

An estimated annual supply of 400 million dry tons of cellulosic biomass could be produced sustainably with technologies and management practices already available in 2008. The amount of biomass deliverable to conversion facilities could probably be increased to about 550 million dry tons by 2020. The panel judges that this quantity of biomass can be produced from dedicated energy crops, agricultural and forestry residues, and municipal solid wastes with minimal effects on U.S. food, feed, and fiber production and minimal adverse environmental effects.

Finding S.2 (see Finding 2.5 in Chapter 2)

Biomass availability could limit the size of a conversion facility and thereby influence the cost of fuel products from any facility that uses biomass irrespective of the conversion approach. Biomass is bulky and difficult to transport. The density of biomass growth will vary considerably from region to region in the United States, and the biomass supply available within 40 miles of a conversion plant will vary from less than 1,000 tons/day to 10,000 tons/day. Longer transportation distances could increase supply but would increase transportation costs and could magnify other logistical issues.

Recommendation S.1 (see Recommendation 2.3 in Chapter 2)

Technologies that increase the density of biomass in the field to decrease transportation cost and logistical issues should be developed. The densification of available biomass enabled by a technology such as field-scale pyrolysis could facilitate transportation of biomass to larger-scale regional conversion facilities.

Finding S.3 (see Finding 2.2 in Chapter 2)

Improvements in agricultural practices and in plant species and cultivars will be required to increase the sustainable production of cellulosic biomass and to achieve the full potential of biomass-based fuels. A sustained research and development (R&D) effort in increasing productivity, improving stress tolerance, managing diseases and weeds, and improving the efficiency of nutrient use will help to improve biomass yields.

Recommendation S.2 (see Recommendation 2.1)

The federal government should support focused research and development programs to provide the technical bases for improving agricultural practices and biomass growth to achieve the desired increase in sustainable production of cellulosic biomass. Focused attention should be directed toward plant breeding, agronomy, ecology, weed and pest science, disease management, hydrology, soil physics, agricultural engineering, economics, regional planning, field-to-wheel biofuel systems analysis, and related public policy.

Finding S.4 (see Finding 2.3 in Chapter 2)

Incentives and best agricultural practices will probably be needed to encourage sustainable production of biomass for production of biofuels. Producers need to grow biofuel feedstocks on degraded agricultural land to avoid direct and indirect competition with the food supply and also need to minimize land-use practices that result in substantial net greenhouse gas emissions. For example, continuation of CRP payments for CRP lands when they are used to produce perennial grass and wood crops for biomass feedstock in an environmentally sustainable manner might be an incentive.

Recommendation S.3 (see Recommendation 2.2 in Chapter 2)

A framework should be developed to assess the effects of cellulosic-feedstock production on various environmental characteristics and natural resources. Such an assessment framework should be developed with input from agronomists, ecologists, soil scientists, environmental scientists, and producers and should include, at a minimum, effects on greenhouse gas emissions and on water and soil resources. The framework would provide guidance to farmers on sustainable production of cellulosic feedstock and contribute to improvements in energy security and in the environmental sustainability of agriculture.

Coal Supply

Deployment of coal-to-liquids technologies would require the use of large quantities of coal and thus an expansion of the coal-mining industry. For example, a 50,000-barrels/day (50,000 bbl/d) plant will use about 7 million tons of coal per year, and 100 such plants producing liquid transportation fuels at 5 million bbl/d would use about 700 million tons of coal per year, which would mean a 70 percent increase in coal consumption. That would require major increases in coal-mining and transportation infrastructure for moving coal to the plants and moving fuel from the plants to the market. Those issues could represent major challenges, but they could be overcome. A key question is the availability of sufficient coal in the United States to support such increased use while supporting the coal-based power industry. A National Research Council evaluation (NRC, 2007) of domestic coal resources concluded as follows:

Federal policy makers require accurate and complete estimates of national coal reserves to formulate coherent national energy policies. Despite significant uncertainties in existing reserve estimates, it is clear that there is sufficient coal at current rates of production to meet anticipated needs through 2030. Further into the future, there is probably sufficient coal to meet the nation’s needs for more than 100 years at current rates of consumption. … A combination of increased rates of production with more detailed reserve analyses that take into account location, quality, recoverability, and transportation issues may substantially reduce the number of years of supply. Future policy will continue to be developed in the absence of accurate estimates until more detailed reserve analyses—which take into account the full suite of geographical, geological, economic, legal, and environmental characteristics—are completed. (p. 4)

Recently, the Energy Information Administration estimated the proven U.S. coal reserves to be about 260 billion tons. A key conclusion was that there are

sufficient coal reserves in the United States to meet the nation’s needs for over 100 years at current rates of consumption, and possibly even with increased rates of consumption. The primary issue probably is not the reserves but increased mining of coal and the opening of many new mines. Increased mining has numerous environmental effects that will need to be dealt with, and there will probably be public opposition to it. Increasing use of coal will undoubtedly increase the cost of coal, which is low relative to the cost of biomass.

Finding S.5 (see Finding 4.1 in Chapter 4)

Despite the vast coal resource in the United States, it is not a forgone conclusion that adequate coal will be mined and be available to meet the needs of a growing coal-to-fuels industry and the needs of the power industry.

Recommendation S.4 (see Recommendation 4.1 in Chapter 4)

The U.S. coal industry, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, the U.S. Department of Energy, and the U.S. Department of Transportation should assess the potential for a rapid expansion of the U.S. coal-supply industry and delineate the critical barriers to growth, environmental effects, and their effects on coal cost. The analysis should include several scenarios, one of which assumes that the United States will move rapidly toward increasing use of coal-based liquid fuels for transportation to improve energy security. An improved understanding of the immediate and long-term environmental effects of increased mining, transportation, and use of coal would be an important goal of the analysis.

Conversion Technologies

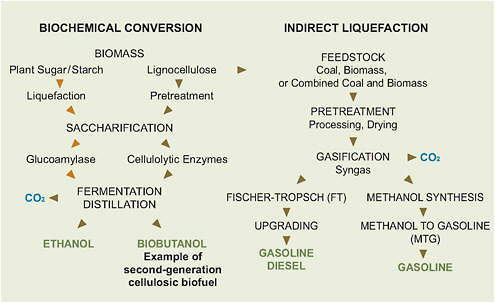

Two key technologies, biochemical and indirect thermochemical conversion, that are required for the conversion of biomass and coal to fuels are illustrated in Figure S.2. Biochemical conversion typically uses enzymes to transform starch (from grains) or lignocelluloses into sugars as intermediates (saccharification), and the sugars are converted to ethanol by microorganisms (fermentation). Indirect thermochemical conversion uses heat and steam to convert biomass or coal into primarily a mixture of carbon monoxide (CO) and hydrogen (H2)—syngas—which can be cleaned and converted to have the right CO:H2 ratio (now referred to as synthesis gas) and then be catalytically converted to liquid fuels, such as diesel

FIGURE S.2 Steps involved in the biochemical conversion of biomass and the thermochemical conversion (indirect route only) of coal, biomass, and combined coal and biomass to liquid transportation fuels.

and gasoline. The CO2 from the fermentation process in biochemical conversion or from the off-gas streams of the thermochemical processes can be captured and stored geologically. Direct liquefaction of coal, which involves adding H2 directly to slurried coal at high temperatures and pressures in the presence of suitable catalysts, represents another route from coal to liquid fuels but is less developed than indirect liquefaction. That route is not shown.

Biochemical Conversion

Biochemical conversion of starch from grains to ethanol (as shown on the left side of Figure S.2) has been deployed commercially. Grain-based ethanol, although important for initiating public awareness and industrial infrastructure for fuel ethanol, is considered by the panel to be a transition to cellulosic ethanol and other advanced cellulosic biofuels. The biomass supplies likely to be available by 2020 technically could be converted to ethanol by biochemical conversion, displace a substantial fraction of petroleum-based gasoline, and reduce greenhouse gas emis-

sions, but the conversion technology has to be demonstrated first and be developed to a commercially deployable state.

Cellulosic ethanol could be the main biochemical route of converting biomass to fuels over the next decade or two. Further R&D could lead to commercial technologies that convert sugars to such other biofuels as butanol and alkanes, which have higher energy densities and could be distributed in the existing infrastructure. Although the panel focused on cellulosic ethanol as the most deployable technology for the next 10 years, it sees a long-term transition to cellulosic conversion to higher alcohols or hydrocarbons—so-called advanced biofuels—as having important long-term potential.

The challenge in biochemical conversion of biomass to fuels is first to break down the recalcitrant structure of the plant cell wall and then to break down the cellulose to five-carbon and six-carbon sugars that can be fermented by microorganisms. The effectiveness of this sugar generation is important for economical biofuel production. The process of production of cellulosic ethanol includes (see Figure S.2) preparation of feedstock to achieve size reduction by grinding or other means; pretreatment of feedstock with steam, hot water, or acid or base to release cellulose from the lignin shield; saccharification—cellulase to hydrolyze cellulose polymers to cellobiose (a disaccharide) and glucose (a monosaccharide) and hemicellulase to break down hemicellulose to monosaccharides; fermentation of the sugars to ethanol; and distillation to separate the ethanol. The CO2 generated in the conversion process and in combustion of the fuel is mostly offset by the CO2 taken up during the growth of the biomass. The unconverted materials are burned in a boiler to generate steam for the distillation; some excess electricity can thus be generated.

As of 2008, no commercial-scale cellulosic ethanol plants were operational. However, the Department of Energy announced in February 2007 that it would invest up to $385 million for six biorefinery projects (two based on gasification) over 4 years to move cellulosic ethanol to the market. When they are fully operational, the total production of the six plants would be 8,000 bbl/d. In addition, a number of private companies are actively pursuing commercialization of cellulosic-ethanol plants. Technologies for cellulosic ethanol will continue to evolve over the next 5–10 years as challenges are overcome and experience is gained in the first technology-demonstration and commercial-demonstration plants. The panel expects deployable, commercialized technology to be in place by 2020 if technology-demonstration plants continue to be built despite the current economic crisis and are rapidly followed by commercial-demonstration plants. Because of lack of commercial

experience, the cost of initial commercial plants could well be higher than estimated by the modeling but decrease as commercial experience is gained.

An expanded transport and distribution infrastructure will be required to replace gasoline with a larger proportion of ethanol produced by biochemical conversion because ethanol cannot be transported in pipelines used for petroleum transport. Ethanol is currently transported by rail or barges and not by pipelines, because it is hygroscopic and can damage seals, gaskets, and other equipment and induce stress-corrosion cracking in high-stress areas. Gasoline vehicles can tolerate gasoline blends with up to 20 percent ethanol. If ethanol is to be used in a fuel at concentrations higher than 20 percent (for example, E85, which is a blend of 85 percent ethanol and 15 percent gasoline), the number of refueling stations will have to be increased to support alternative-fuel vehicles designed for alcohol fuels. The transport and distribution of synthetic diesel and gasoline produced with thermochemical conversion do not pose the same challenge because they are compatible with the existing infrastructure for petroleum-based fuels.

The key process-related challenges in R&D and demonstration that need to be addressed before widespread commercialization are as follows: to improve the effectiveness of pretreatment to remove and hydrolyze the hemicellulose, separate the cellulose from the lignin, and loosen the cellulose structure; to reduce the production cost of the enzymes for converting cellulose to sugars; to reduce operating costs by developing more effective enzymes and more efficient microorganisms for converting the sugar products of biomass deconstruction to biofuels; to demonstrate the biochemical conversion technology on a commercial scale; and to begin to optimize capital costs and operating costs. The size of a biorefinery will probably be limited by the supply of biomass available from the surrounding regions. That size limitation could result in loss of potential economies of scale that characterize large plants.

Finding S.6 (see Finding 3.2 in Chapter 3)

Process improvements in cellulosic-ethanol technology are expected to be able to reduce the plant-related costs associated with ethanol production by up to 40 percent over the next 25 years. Over the next decade, process improvements and cost reductions are expected to come from evolutionary developments in technology, from learning gained through commercial experience and increases in scale of operation, and from research and engineering in advanced chemical and biochemical catalysts that will enable their deployment on a large scale.

Recommendation S.5 (see Recommendation 3.2 in Chapter 3)

The federal government should continue to support research and development to advance cellulosic-ethanol technologies. R&D programs should be pursued to resolve the major technical challenges facing ethanol production from cellulosic biomass: pretreatment, enzymes, tolerance to toxic compounds and products, solids loading, engineering microorganisms, and novel separations for ethanol and other biofuels. A long-term perspective on the design of the programs and allocation of limited resources is needed; high priority should be placed on programs that address current problems at a fundamental level but with visible industrial goals.

Recommendation S.6 (see Recommendation 3.3 in Chapter 3)

The pilot and commercial-scale demonstrations of cellulosic-ethanol plants should be complemented by a closely coupled research and development program. R&D is necessary to resolve issues that are identified during demonstration and to reduce costs of sustainable feedstock acquisition. Industrial experience shows that such reductions typically occur as processes go through multiple phases of implementation and expansion.

Finding S.7 (see Finding 3.4 in Chapter 3)

Biochemical conversion processes, as configured in cellulosic-ethanol plants, produce a stream of relatively pure CO2 from the fermenter that can be dried, compressed, and made ready for geologic storage or used in enhanced oil recovery with little additional cost. Geologic storage of the CO2 from biochemical conversion of plant matter (such as cellulosic biomass) further reduces greenhouse gas life-cycle emissions from advanced biofuels, so their greenhouse gas life-cycle emissions would become highly negative.

Recommendation S.7 (see Recommendation 3.5 in Chapter 3)

Because geologic storage of CO2 from biochemical conversion of biomass to fuels could be important in reducing greenhouse gas emissions in the transportation sector, it should be evaluated and demonstrated in parallel with the program of geologic storage of CO2 from coal-based fuels.

Finding S.8 (see Finding 3.3 in Chapter 3)

Future improvements in cellulosic technology that entail invention of biocatalysts and biological processes could produce fuels that supplement ethanol production in the next 15 years. In addition to ethanol, advanced biofuels (such as lipids, higher alcohols, hydrocarbons, and other products that are easier to separate than ethanol) should be investigated because they could have higher energy content and would be less hygroscopic than ethanol and therefore could fit more smoothly into the current petroleum infrastructure than could ethanol.

Recommendation S.8 (see Recommendation 3.4 in Chapter 3)

The federal government should ensure that there is adequate research support to focus advances in bioengineering and the expanding biotechnologies on developing advanced biofuels. The research should focus on advanced biosciences—genomics, molecular biology, and genetics—and biotechnologies that could convert biomass directly to produce lipids, higher alcohols, and hydrocarbons fuels that can be directly integrated into the existing transportation infrastructure. The translation of those technologies into large-scale commercial practice poses many challenges that need to be resolved by R&D and demonstration if major effects on production of alternative liquid fuels from renewable resources are to be realized.

Finding S.9 (see Finding 5.1 in Chapter 5)

The need to expand the delivery infrastructure to meet a high volume of ethanol deployment could delay and limit the penetration of ethanol into the U.S. transportation-fuels market. Replacing a substantial proportion of transportation gasoline with ethanol will require a new infrastructure for its transport and distribution. Although the cost of delivery is a small fraction of the overall fuel-ethanol cost, the logistics and capital requirements for widespread expansion could present many hurdles if they are not planned for well.

Recommendation S.9 (see Recommendation 5.1 in Chapter 5)

The U.S. Department of Energy and the biofuels industry should conduct a comprehensive joint study to identify the infrastructure system requirements of, research and development needs in, and challenges facing the expanding biofuels

industry. Consideration should be given to the long-term potential of truck or barge delivery versus the potential of pipeline delivery that is needed to accommodate increasing volumes of ethanol. The timing and role of advanced biofuels that are compatible with the existing gasoline infrastructure should be factored into the analysis.

Thermochemical Conversion

Indirect liquefaction converts coal to liquid fuels (CTL), biomass to liquid fuels (BTL), or mixtures of coal and biomass to liquid fuels (CBTL) by gasifying the feedstocks to produce syngas, cleaning and adjusting the H2:CO ratio, and then catalytically converting the synthesis gas with Fischer-Tropsch (FT) technology to high-cetane, clean diesel, and some naphtha (which can be upgraded to gasoline). The synthesis gas can also be converted to methanol with commercial technology, and methanol-to-gasoline (MTG) technology can then be used to produce high-octane gasoline from the methanol (see Figure S.2). Those technologies can be integrated with technologies that compress the CO2 emitted during production and store it in Earth’s subsurface (CCS), such as in deep saline aquifers. Unlike ethanol, the gasoline and diesel produced via FT and MTG are fully compatible with the existing infrastructure and vehicle fleet.

Gasification has been used commercially around the world for nearly a century by the chemical, refining, and fertilizer industries and for more than 10 years by the electric-power industry. More than 420 gasifiers are in use in some 140 facilities worldwide; 19 plants are operating in the United States. Coal gasification is commercially deployable today with any of several gasification systems that are being commercially used. Application in CTL fuels and other applications of gasification will lead to further improvements in the technology, and it will have become more robust and efficient by 2020. The improvements are part of the usual evolution of any new technology. Combined coal and biomass gasification is close to being commercially deployable, and further commercial application will make it more robust and efficient and enhance its ability to use higher fractions of biomass by 2020. Biomass gasification has been commercially demonstrated but requires more operational experience to make it robust and to allow well-informed designs.

FT technology was commercialized at the South African firm Sasol’s complexes beginning in the middle 1950s. Sasol now produces transportation fuels from coal at more than 165,000 bbl/d, and large plants convert natural gas to

synthesis gas, which is converted to diesel and gasoline with the FT process. FT synthesis technology can be considered commercially deployable today. Like several other ready-to-deploy technologies, it will undergo substantial process improvement by 2020, which will lead to more robust and efficient technology for producing liquid transportation fuels, and catalyst improvements for coal applications can be expected.

In technologies based on methanol synthesis, synthesis gas is converted to methanol with available commercial technology in plants as large as 6,000 tons/day. The methanol can be used directly or be upgraded into high-octane gasoline with a proprietary catalytic process developed by ExxonMobil and referred to as the MTG process, which was commercialized in New Zealand in the late 1980s. Standard MTG technology is considered by the panel to be commercially deployable today—and several projects are moving toward commercial deployment. Several variations of the technology are ready for commercial demonstration and could lead to improvements in the standard MTG technology.

Although the technologies involved in thermochemical conversion of coal have all been commercialized and have years of operating experience, geologic storage of CO2 has not been adequately developed and demonstrated. In the case of power generation from coal, most of the costs for CCS are in the CO2-capture part of the process, and this technology has been demonstrated on a large scale. However, geologic storage of CO2 in the subsurface has not been developed and demonstrated to the point where there is sufficient confidence in its long-term efficiency and efficacy to embark on commercial application on the scale required. The CO2 emissions from CTL technology are high because of the high heat needed for the process and the high carbon content of coal (which has about twice the carbon content of oil); even with geologic storage of CO2, the well-to-wheel emissions from CTL are about the same as those of gasoline because, as with any hydrocarbon fuel, CO2 is released when the fuel is combusted in vehicles.

Inclusion of biomass in the feedstock with coal decreases greenhouse gas life-cycle emissions because the biomass takes up atmospheric CO2 during its growth. It is possible to optimize the biomass-plus-coal indirect liquefaction process to produce liquid fuels that have somewhat lower greenhouse gas life-cycle emissions than gasoline has and even to make carbon-neutral liquid fuels if geologic storage of CO2 is used. Although the notion of gasifying mixtures of coal and biomass to produce liquid fuels is relatively new and commercial experience is small, several demonstration units are running in Europe. Gasifiers for biomass alone, designed around limited biomass availability, operate on a smaller scale than do those for

coal and so will be more expensive because of the diseconomies of scale of small plants. However, the fuels produced from such plants can have greenhouse gas life-cycle emissions that are close to zero without geologic storage of CO2. Thermochemical processes that use biomass only can therefore be carbon neutral, as is biochemical conversion, and can have highly negative carbon emissions if geologic storage of CO2 is used. The panel judges that the technology for cofeeding biomass and coal is close to being ready for commercial deployment, but commercial experience with the technology is needed. Stand-alone biomass gasification technology is probably 5–8 years away from commercial scale-up.

The subject of greatest uncertainty in connection with conversion of coal and biomass to fuels is the geologic storage of CO2. As of 2008, few commercial-scale geologic-storage demonstrations have been carried out or are ongoing. Well-monitored commercial-scale demonstrations are needed to gather data sufficient to assure industry and governments as to the long-term viability, costs, and safety of geologic CO2 storage and to develop procedures for site choice, permitting, operation, regulation, and closure. The political and commercial acceptability of geologic storage of CO2 is critical for the commercial viability of thermochemical technology. The estimates of potential CCS costs of $10–$15/tonne of CO2 avoided are “bottom-up” largely on the basis of engineering estimates of expenses for transport, land purchase, permitting, drilling, required capital equipment, storing, capping wells, and monitoring for an additional 50 years. However, uncertainty about the regulatory environment arising from concerns of the general public and policy makers has the potential to raise storage costs and slow commercialization of thermochemical fuel technology (Appendix K). Ultimate requirements for design, monitoring, carbon-accounting procedures, liability for long-term monitoring of geologically stored CO2, and associated regulatory frameworks depend on future commercial-scale demonstrations of geologic storage of CO2. The commercial demonstrations will have to be pursued aggressively in the next few years if thermochemical conversion of biomass and coal with geologic storage of CO2 is to be ready for commercial deployment by 2020.

As a first step toward accelerating the commercial demonstration of CTL and CBTL technology and addressing the CO2-storage issue, commercial-scale demonstration plants could serve as sources of CO2 for geologic-storage demonstration projects. So-called capture-ready plants that vent CO2 would create liquid fuels with higher CO2 emissions per unit of usable energy than petroleum-based fuels; their commercialization should not be encouraged unless the plants are integrated with geologic storage of CO2 at their start-up.

Direct liquefaction of coal—which involves relatively high temperature, high hydrogen pressure, and liquid-phase conversion of coal directly to liquid products—has a long history, as does FT. Direct-liquefaction products generally are heavy liquids that require upgrading to liquid transportation fuels. The technology is not ready for commercial deployment. Furthermore, the panel’s ability to estimate costs and performance was limited by the lack of recent detailed design studies in the available literature.

The three most important challenges in R&D and demonstration facing commercialization of thermochemical technologies are

-

Immediate construction of a small number of commercial first-mover projects combined with geologic storage of CO2 to move the technology toward reduced cost, improved performance, and robustness. The commercial first-mover projects would have a major R&D component to focus on solving issues and problems identified in the operation and to develop technology for specific improvements.

-

R&D programs associated with commercial-scale geologic CO2 storage demonstrations that involve detailed geologic analysis and a broad array of monitoring tools and techniques to provide the understanding and data on which future commercial projects will depend.

-

R&D on gasification of biomass or combined biomass and coal, which has potential CO2-reduction benefits, is critical to bring this technology to commercial deployment. In particular, penalties associated with the preprocessing of biomass, the choice of a best gasifier for a given biomass type, and the technical problems in feeding biomass to high-pressure gasification systems have to be resolved.

Finding S.10 (see Finding 4.2 in Chapter 4)

Technologies for the indirect liquefaction of coal to transportation fuels are commercially deployable today; but without geologic storage of the CO2 produced in the conversion, greenhouse gas life-cycle emissions will be about twice those of petroleum-based fuels. With geologic storage of CO2, CTL transportation fuels could have greenhouse gas life-cycle emissions equivalent to those of equivalent petroleum-derived fuels.

Finding S.11 (see Finding 4.7 in Chapter 4)

Technologies for the indirect liquefaction of coal to produce liquid transportation fuels with greenhouse gas life-cycle emissions equivalent to those of petroleum-based fuels can be commercially deployed before 2020 only if several first-mover plants are started up soon and if the safety and long-term viability of geologic storage of CO2 is demonstrated in the next 5–6 years.

Finding S.12 (see Finding 4.3 in Chapter 4)

Indirect liquefaction of combined coal and biomass to transportation fuels is close to being commercially deployable today. Coal can be combined with biomass at a ratio of 60:40 (on an energy basis) to produce liquid fuels that have greenhouse gas life-cycle emissions comparable with those of petroleum-based fuels if CCS is not implemented. With CCS, production of fuels from coal and biomass would have a carbon balance of about zero to slightly negative.

Recommendation S.10 (see Recommendation 4.4 in Chapter 4)

A program of aggressive support for first-mover commercial plants that produce coal-to-liquid transportation fuels and coal-and-biomass-to-liquid transportation fuels with integrated geologic storage of CO2 should be undertaken immediately to address U.S. energy security and to provide fuels with greenhouse gas emissions similar to or less than those of petroleum-based fuels. The demonstration and deployment of “first-mover” coal or coal-and-biomass plants should be encouraged on the basis of the primary technologies, including CCS to demonstrate the technological viability of CTL and CBTL fuels and to reduce the technical and investment risks associated with funding of future plants. If decisions to proceed with commercial demonstrations are made soon so that the plants could start up in 4–5 years and if CCS is demonstrated to be safe and viable, those technologies would be commercially deployable by 2020.

Finding S.13 (see Finding 4.8 in Chapter 4)

The technology for producing liquid transportation fuels from biomass or from combined biomass and coal via thermochemical conversion has been demonstrated but requires additional development to be ready for commercial deployment.

Recommendation S.11 (see Recommendation 4.6 in Chapter 4)

Key technologies should be demonstrated for biomass gasification on an intermediate scale, alone and in combination with coal, to obtain the engineering and operating data required to design commercial-scale synthesis gas-production units.

Finding S.14 (see Finding 4.4 in Chapter 4)

Geologic storage of CO2 on a commercial scale is critical for producing liquid transportation fuels from coal without a large adverse greenhouse gas impact. This is similar to the situation for producing power from coal.

Recommendation S.12 (see Recommendation 4.2 in Chapter 4)

The federal government should continue to partner with industry and independent researchers in an aggressive program to determine the operational procedures, monitoring, safety, and effectiveness of commercial-scale technology for geologic storage of CO2. Three to five commercial-scale demonstrations (each with about 1 million tonnes of CO2 per year and operated for several years) should be set up within the next 3–5 years in areas of several geologic types.

The demonstrations should focus on site choice, permitting, monitoring, operation, closure, and legal procedures needed to support the broad-scale application of geologic storage of CO2. The development of needed engineering data and determination of the full costs of geologic storage of CO2—including engineering, monitoring, and other costs based on data developed from continuing demonstration projects—should have high priority.

COSTS, GREENHOUSE GAS EMISSIONS, AND SUPPLY

This section compares the life-cycle costs, CO2 life-cycle emissions,2 and potential supply of the alternative-fuel technologies deployable by 2020 by analyzing the supply chain that begins with the biomass and coal feedstocks and ends with

alternative liquid fuels. The result of the analysis is a supply curve of potential alternative liquid fuels that use biomass, coal, or combined biomass and coal as feedstocks on the basis of technologies deployable by 2020. The supply curve does not represent the amounts of fuels that would be commercially deployed. The actual supply in 2020 could well be smaller than the potential supply because there are important lags in decisions to construct new conversion plants and in construction, as discussed in the section “Deployment of Alternative Liquid Transportation Fuels” below. In addition, some of the coal and biomass supplies that appear to be economical might not be made available for conversion to alternative fuels because of logistical, infrastructure, and agricultural organization issues or because they would have already been committed to power plants. The analysis shows how the potential supply curve might change with alternative CO2 prices and alternative capital costs. As mentioned earlier, the panel worked with several research groups to develop the costs and CO2 life-cycle emission for the individual conversion technologies and the cost of biomass.

To examine the potential supply of liquid transportation fuels from nonpetroleum sources, the panel developed estimates of the unit costs and quantities of various biomass sources that could be made available. The panel’s analysis was based on land that is currently not used for growing foods, although the panel cannot ensure that none of that land will be used for food production in the future. The estimates of biomass supply were combined with estimates of supply of corn grain to satisfy the current legislative requirement to produce 15 billion gallons of ethanol. The analysis allowed the estimation of a supply curve for biomass that shows the quantities of biomass feedstocks that would potentially be available at the various unit costs. Coal was assumed to be available in sufficient quantities at a constant unit cost if used with biomass in thermochemical conversion processes. Quantitative analyses were developed to compare alternative pathways to convert biomass, coal, or combined coal and biomass to liquid transportation fuels using thermochemical technologies. Biochemical technology that produced ethanol from biomass was also evaluated quantitatively on as consistent a basis as possible. Various combinations of biomass feedstocks could, in principle, be converted with either thermochemical or biochemical conversion processes.3 However, rather than examining all possible combinations, the panel first examined the cost of and CO2 emission associated with each of the various

thermochemical and biochemical conversion processes by using a generic biomass feedstock with approximately a median cost and biochemical composition (the panel used Miscanthus in the analysis) and then examined the costs, supplies, and CO2 emissions associated with one thermochemical conversion process and one biochemical conversion process that would use each of the different biomass feedstocks.

The analyses involved a set of assumptions, changes in which would likely change the estimated supply curve:

-

The panel’s analyses assume that all available CRP land discussed earlier will be made available for growing biomass for liquid fuels. Conversion plants that use biomass as feedstock by itself and in combination with coal (60 percent coal and 40 percent biomass on an energy basis) would have the capacity of using about 4,000 dry tons of biomass per day.

-

All product prices are assumed to be without government subsidies. The costs of CO2 avoided—which include the cost of drying, compression, pipelining, and geologic storage of CO2—are estimates of engineering costs to implement geologic storage and are in the range of $10–15/tonne of CO2 avoided.

-

If a carbon price is imposed, the assumption is that it applies to the entire life-cycle CO2 net emission, which is the balance of CO2 removal from the atmosphere by plants, CO2 released in the production of biomass (for example, CO2 released from machinery used in the production), and emissions from conversion of feedstock to fuels and from combustion of the liquid fuels. A fuel that removes more CO2 from the atmosphere than it produces over its life cycle would receive a net payment for CO2.

-

The panel’s analyses assume that no indirect greenhouse gas emissions result from land-use changes in the growing and harvesting of biomass. All biomass volumes in Chapter 2 were estimated under the constraint that they could be grown and harvested without creating indirect greenhouse gas emissions.

-

The price of subbituminous Illinois no. 6 coal is assumed to be $42 per dry ton.

-

Electricity produced as a coproduct is assumed to be valued at $80/MWh in the absence of any price placed on CO2.

Costs and Carbon Dioxide Emissions

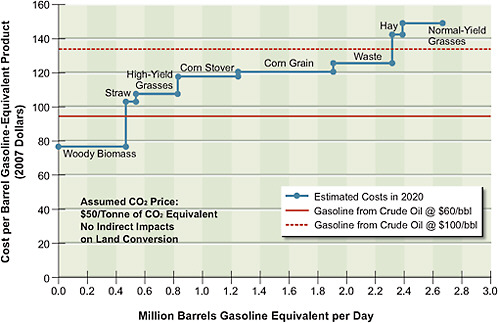

The estimated 2020 supply function for biomass costs versus availability is shown in Figure S.3. The costs of two feedstocks—corn grain and hay—are based on recent market prices. In particular, it is assumed that corn price will have dropped sharply from the 2008 high of $7.88/bushel to $3.17/bushel in 2020, corresponding to $130 per dry ton, a price more consistent with its historical levels. The price of dryland or field-run hay is assumed to be $110/ton, similar to historical prices. Finally, the cost of using wastes is based on a rough estimate of the costs of gathering, transporting, and storing municipal waste. Such costs can be expected to be highly variable, but the panel assumes that gathering, transporting, and storing add up to $51 per dry ton.

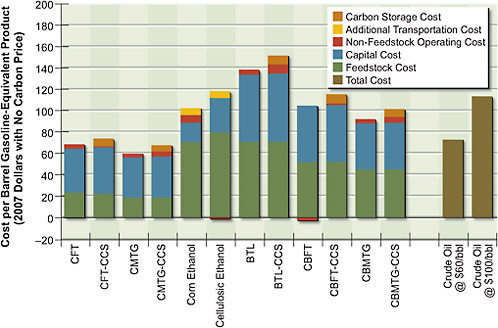

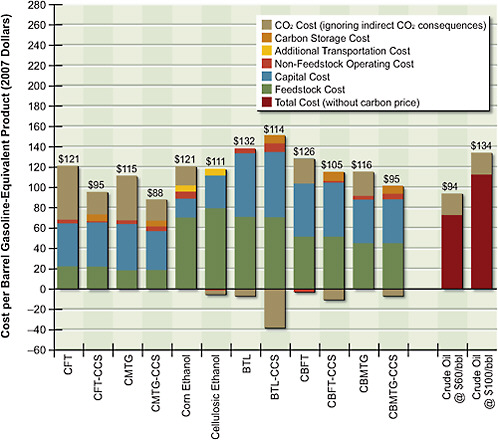

The costs of producing alternative liquid fuels through the various pathways were estimated on the basis of feedstock, capital, and operating costs; conversion efficiencies; and the assumptions outlined above. Figure S.4 shows the esti-

FIGURE S.3 Supply function for biomass feedstocks in 2020. High-yield grasses include Miscanthus and normal-yield grasses include switchgrass and prairie grasses.

FIGURE S.4 Costs of alternative liquid fuels produced from coal, biomass, or coal and biomass with zero carbon price.

Note: BTL = biomass-to-liquid fuel; CBFT = coal-and-biomass-to-liquid fuel, Fischer-Tropsch; CBMTG = coal-and-biomass-to-liquid fuel, methanol-to-gasoline; CCS = carbon capture and storage; CFT = coal-to-liquid fuel, Fischer-Tropsch; CMTG = coal-to-liquid fuel, methanol-to-gasoline.

mated gasoline-equivalent4 costs of alternative liquid fuels, without a CO2 price, produced from biomass (B), coal (C), or combined coal and biomass (CB). As indicated above, liquid fuels would be produced with biochemical conversion to produce ethanol from a generic biomass (cellulosic ethanol), thermochemical conversion via FT, or MTG. For thermochemical conversion, FT and MTG are shown both with and without CCS. The supply of ethanol produced from corn grain is also included in the figure. For comparison, costs of gasoline are shown for two crude-oil prices: $60/bbl and $100/bbl (that is, $73/bbl and $113/bbl of gasoline equivalent). Results are also shown in Table S.3.

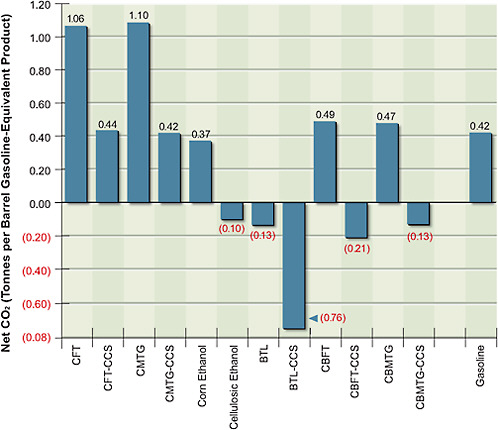

TABLE S.3 Estimated Costs of Fuel Products With and Without a CO2 Equivalent Price of $50/tonne

Figure S.5 shows the net CO2 emissions per gasoline-equivalent barrel produced by various production pathways. The CO2 released on combustion of the fuel is similar among the various pathways, with ethanol releasing less CO2 than either gasoline or synthetic diesel and gasoline produced from coal or combined coal and biomass (that is, CFT, CMTG, CBFT, and CBMTG). The large variation in net releases is the result of the large variations in the CO2 taken from the atmosphere in growing biomass and the large variations in the release of CO2 into the atmosphere in the conversion process. CO2 emission from corn-grain ethanol is slightly lower than that from conventional gasoline. In contrast, CO2 emission from cellulosic ethanol without CCS is close to zero.

Figure S.4 shows that CTL fuel products with and without geologic CO2 storage are cost-competitive at gasoline-equivalent prices of about $70/bbl and $65/bbl, respectively (this represents equivalent crude-oil prices of around $50–55/bbl). Gasoline prices from MTG are similar. Figure S.5 shows that without CCS the process vents a large amount of CO2, and the CO2 life-cycle emission

FIGURE S.5 Estimated carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions over the life cycle of alternative fuels, from the mining and harvesting of resources to the conversion process to the consumption of fuels.

Note: BTL = biomass-to-liquid fuel; CBFT = coal-and-biomass-to-liquid fuel, Fischer-Tropsch; CBMTG = coal-and-biomass-to-liquid fuel, methanol-to-gasoline; CCS = carbon capture and storage; CFT = coal-to-liquid fuel, Fischer-Tropsch; CMTG = coal-to-liquid fuel, methanol-to-gasoline.

is about twice that from petroleum-based gasoline. With CCS, the CO2 life-cycle emission is about the same as that from petroleum-based gasoline.

The biochemical conversion of biomass produces fuels that are more expensive than CTL fuels because the conversion plants are smaller and the feedstock more expensive—biomass costs almost 4 times as much as coal on an energy-equivalent basis. The production cost of cellulosic ethanol is around $115/bbl on a gasoline-equivalent basis. The cost of thermochemical conversion of biomass,

without coal, is higher than cellulosic ethanol on an energy-equivalent basis and has the potential of large negative net releases of CO2 with geologic storage; that is, the process involves a net removal of CO2 from the atmosphere. For BTL and venting of CO2, the estimated fuel cost is $140/bbl if electricity is sold back to the grid at $80/MWh; with geologic storage of CO2, it is $150/bbl if electricity is sold back to the grid at $80/MWh. The results of the relatively small cofed coal and biomass plant (total feed, 8000 tons/day) are particularly interesting. Fuels produced by that plant cost about $95/bbl on a gasoline-equivalent basis without CCS, and CO2 atmospheric releases from plants with CCS are negative. Those results point to the importance of that option in the U.S. energy strategy.

The important influence of a carbon price on fuel price is shown in Figure S.6. It is important to note that Figure S.6 shows the breakdown of all costs, including negative costs such as credit from electricity generation or from carbon uptake. The negative costs must be subtracted from the positive costs to obtain the actual costs. For example, the cost of BTL with CCS is $151/bbl–$37/bbl = $114/bbl. CO2 emission from corn-grain ethanol is slightly lower than that from gasoline. In contrast, CO2 emission from cellulosic ethanol without CCS is close to zero.

Figure S.6 shows that a CO2 price of $50/tonne significantly increases the costs of the fossil-fuel options, including the costs of petroleum-based gasoline. The carbon price brings the cost of biochemical conversion options down to about $110/bbl (crude price, about $95/bbl). The large amount of CO2 vented in the CTL process without CO2 storage almost doubles the cost of product once the carbon price of $50/tonne of CO2 is imposed.

Inclusion of a carbon price does not increase the total costs of all pathways. For example, although thermochemical conversion of biomass costs about $140/bbl of gasoline equivalent without CCS, the produced fuels become competitive with petroleum-based fuels at $115/bbl of gasoline equivalent with the carbon price and CCS. In general, if any pathway takes more CO2 from the atmosphere than it releases in other parts of its life cycle, the inclusion of a carbon price reduces the total cost of producing liquid fuel by that pathway. Those estimates are all based on costs of small gasification units operating at a feed rate of 4,000 tons/day. Each of those units is capital-intensive. Therefore, larger units can be expected to be deployed in regions where potential biomass availability is large—for example, 10,000 tons/day. Such units could result in much lower costs.

FIGURE S.6 Cost of alternative liquid fuels produced from coal, biomass, or coal and biomass with a CO2-equivalent price of $50/tonne. Negative cost elements must be subtracted from the positive elements; the number at the top of each bar indicates the net costs.

Note: BTL = biomass-to-liquid fuel; CBFT = coal-and-biomass-to-liquid fuel, Fischer-Tropsch; CBMTG = coal-and-biomass-to-liquid fuel, methanol-to-gasoline; CCS = carbon capture and storage; CFT = coal-to-liquid fuel, Fischer-Tropsch; CMTG = coal-to-liquid fuel, methanol-to-gasoline.

Costs and Supply

As noted previously, the cost estimates for biochemical conversion and thermochemical conversion are based on one generic biomass source. Figures S.4 and S.6 do not show how much fuel could be produced at the estimated costs. To provide

a complete supply function for alternative liquid fuels, the supply function from Figure S.3 for all biomass feedstocks has been combined with the conversion cost estimates. (The potential supply of gasoline and diesel from CTL technology is discussed below in the section “Deployment of Alternative Liquid Transportation Fuels.”) The results are shown in Figures S.7 and S.8. Figure S.7 shows the potential gasoline-equivalent supply of ethanol from biochemical conversion of lignocellulosic biomass and corn grain with 2020-deployable technology. The supply of grain ethanol satisfies the current legislative requirement to produce 15 billion gallons of ethanol in 2022. Figure S.7 shows potential supply, not the panel’s projected penetration of cellulosic ethanol in 2020; it does not incorporate lags in implementation of the technology that result from the need to permit and build the infrastructure to produce and transport the alternative liquid fuels. The estimated supply of synthetic gasoline and diesel (G/D) derived from coal and biomass is shown in Figure S.8. Two supply functions are shown: one with CCS and

FIGURE S.7 Estimated supply of cellulosic ethanol plus corn-grain ethanol at different price points in 2020. The red solid and dotted lines show the supply of crude oil at $60/bbl and $100/bbl for comparison.

FIGURE S.8 Estimated supply of gasoline and diesel produced by thermochemical conversion of combined coal and biomass via Ficher-Tropsch with or without carbon capture and storage at different price points in 2020.

the other without CCS. The comparison shows that if the CCS technologies are viable and a CO2-eq price of $50/tonne is implemented, for each feedstock it will be less expensive to use CCS than to release the CO2 into the atmosphere.

Either of the production processes underlying Figures S.7 and S.8 would use the same supplies of biomass. Therefore, the quantities cannot be added. If all the production (in addition to ethanol produced from corn grain) is based on cellulosic conversion, Figure S.7 would be potentially applicable. If all production is based on thermochemical conversion cofed with biomass and coal, Figure S.8 would be potentially applicable. Most likely, some of the production would be based on cellulosic processes and some on thermochemical processes, so the potential supply function would lie between the two supply functions shown. If corn-grain ethanol has not been phased out by then, it would add about 0.67 million bbl/day of gasoline-equivalent production to the supply.

To put the results in perspective, the light-duty vehicle gasoline and diesel use in the United States in 2008 is estimated to be about 9 million barrels of oil equivalent per day (1 bbl of crude oil produces about 0.85 bbl of gasoline equivalent).

Total liquid fuel used in the United States in 2008 was 21 million barrels per day, of which 14 million was used for transportation and 12 million was imported. Thus, 2 million barrels of gasoline-equivalent ethanol produced from cellulosic biomass and the 0.7 million barrels of gasoline-equivalent ethanol produced from corn grain have the potential to replace about 30 percent of the petroleum-based fuel consumed in the United States by light-duty vehicles.

The potential supply of gasoline or diesel fuel from thermochemical CBTL with CCS is greater than that from biochemical or thermochemical conversion of cellulosic biomass. The costs of thermochemical CBTL are lower than those of either biochemical or thermochemical conversion of biomass. The cost difference occurs because coal is a lower-cost feedstock than biomass. In addition, cofeeding coal and biomass allows a larger plant to be built and reduces capital costs per unit volume of product. Thus, the combination of coal with biomass allows a larger amount of alternative fuels to be produced than would be possible with biomass alone because the quantity of biomass limits overall production. The addition of coal increases the total amount of liquids that could be produced from a fixed quantity of biomass. Using coal and biomass at 60 and 40 percent, respectively, on an energy basis, almost 4 million barrels per day of gasoline equivalent can potentially be displaced from transportation (60 billion gallons of gasoline equivalent per year, or 45 percent of gasoline and diesel used by light-duty vehicles in 2008). That assumes that all of the 550 million dry tons of cellulosic biomass sustainably grown for fuel will be used for CBTL fuel production, so the estimates represent the maximum potential supply.

Finding S.15 (see Finding 6.1 in Chapter 6)

Alternative liquid transportation fuels from coal and biomass have the potential to play an important role in helping the United States to address issues of energy security, supply diversification, and greenhouse gas emissions with technologies that are commercially deployable by 2020.

-

With CO2 emissions similar to those from petroleum-based fuels, a substantial supply of alternative liquid transportation fuels can be produced with thermochemical conversion of coal with geologic storage of CO2 at a gasoline-equivalent cost of $70/bbl.

-

With CO2 emissions substantially lower than those from petroleum-based fuels, up to 2 million barrels per day of gasoline-equivalent

-

fuel can technically be produced with biochemical or thermochemical conversion of the estimated 550 million dry tons of biomass available in 2020 at a gasoline-equivalent cost of about $115–140/bbl. Up to 4 million barrels per day of gasoline-equivalent fuel can be technically produced if the same amount of biomass is combined with coal (60 percent coal and 40 percent biomass on an energy basis) at a gasoline-equivalent cost of about $95–110/bbl. However, the technically feasible supply does not equal the actual supply inasmuch as many factors influence the market penetration of fuels.

DEPLOYMENT OF ALTERNATIVE LIQUID TRANSPORTATION FUELS

The discussion above has focused on the potential supply of alternative fuels from technologies ready to be deployed commercially by 2020, but the potential supply does not translate to the alternative supply that could be available by 2020. Apart from technological readiness, the penetration rates of alternative liquid fuels into the market will depend on many factors, including oil price, carbon taxes, construction environment, and labor availability. The panel developed a few plausible scenarios to illustrate the lag between when technology becomes commercially deployable, and when substantial market penetration will be seen.

Deployment of Cellulosic-Ethanol Plants

For biochemical conversion to cellulosic ethanol, the panel developed two scenarios on the basis of the current activities of demonstration plants, the announced commercial plants, the U.S. Department of Energy roadmap, and the rate of construction of grain-ethanol plants. The two scenarios assume that the cellulosic-ethanol capacity by 2015 will be 1 billion gallons per year, resulting from overall commercial development and demonstration activities, and that capacity-building beyond 2015 tracks one of two scenarios based on the capacity-building experienced by grain ethanol. One scenario assumes the maximum capacity-building experienced for grain ethanol (about a 25 percent yearly increase in capacity over a 6-year period); the second is a scenario of aggressive capacity-building of about twice that achieved for grain ethanol. The two scenarios project 7–12 billion gallons of cellulosic ethanol per year by 2020. Continued aggressive capacity-building

could achieve the Renewable Fuel Standard5 mandate capacity of 16 billion gallons of cellulosic ethanol per year by 2022, but it would be a stretch. Continued aggressive capacity-building could yield 30 billion gallons of cellulosic ethanol per year by 2030 and up to 40 billion gallons per year by 2035, consuming about 440 million dry tons of biomass per year and replacing 1.7 million barrels of petroleum-based fuels per day.

Deployment of Alternative Liquid Fuels from Coal-to-Liquids Plants with Carbon Capture and Storage

If commercial demonstrations of CTL with CCS are started immediately (as discussed in Recommendations S.10 and S.12) and CCS is proved viable and safe by 2015, commercially viable plants could be starting up before 2020. The growth rate after that could be about two or three plants per year. That would reduce dependence on imported oil but would increase CO2 emission from transportation. At a build-out rate of two plants (at 50,000 bbl/d of fuel) per year, liquid fuel would be produced at 2 million barrels per day from 390 tons of coal per year by 2035 at a total cost of about $200 billion for all the plants built. At a build-out rate of three plants per year, liquid fuels would be produced at 3 million barrels per day from about 580 million tons of coal per year. The latter case would replace about one-third of the current U.S. oil use in light-duty transportation and increase U.S. coal production by 50 percent. At a build out of three plants starting up per year, five or six plants would be under construction at any time.

Deployment of Alternative Fuels from Coal-and-Biomass-to-Liquids Plants

For cofed biomass and coal plants, the technology is close to being developed, and several commercial plants without CCS have started cofeeding biomass. However, gaining operational experience in the plants with CCS is critical; CCS will probably be required, and plants are going through early commercialization to gain operating experience and to reduce costs. Because coal-and-biomass plants are much smaller than CTL plants (plant size, one-fifth the size of CTL plants,

or fuel production at 10,000 bbl/d) and biomass feed rates are similar to those in cellulosic biochemical conversion plants, penetration rates should follow the cellulosic-plant build out more closely. But most likely, the coal-and-biomass build out will be much slower than the aggressive cellulosic-plant buildout presented above because of issues of siting the plants near both biomass and coal production and because plant design is more complex. The panel assumed that penetration rates for the coal-and-biomass plants would be slightly less than the rate for the cellulosic-ethanol build-out case that follows the experience of grain ethanol discussed above (which has experienced a 25 percent growth rate). At a 20 percent growth rate until 2035 with 280 plants in place, 2.5 million barrels of gasoline equivalent would be produced per day. That would consume about 300 million dry tons of biomass and about 250 million tons of coal per year—less than the projected biomass availability. Siting to have access to both biomass and coal is probably the limiting factor for CBTL plants. This analysis shows that the rates of capacity growth would have to exceed historical rates considerably if 550 million dry tons of biomass per year is to be converted to liquid fuels by 2035.

Finding S.16 (see Finding 6.2 in Chapter 6)

If commercial demonstration of cellulosic-ethanol plants is successful and commercial deployment begins in 2015 and if it is assumed that capacity will grow by 50 percent each year, cellulosic ethanol with low CO2 life-cycle emissions can replace up to 0.5 million barrels of gasoline equivalent per day by 2020 and 1.7 million barrels per day by 2035.

Finding S.17 (see Finding 6.3 in Chapter 6)

If commercial demonstration of coal-and-biomass-to-liquid plants with carbon capture and storage is successful and the first commercial plants start up in 2020 and if it is assumed that capacity will grow by 20 percent each year, coal-and-biomass-to-liquid fuels with low CO2 life-cycle emissions can replace up to 2.5 million barrels of gasoline equivalent per day by 2035.

Finding S.18 (see Finding 6.4 in Chapter 6)

If commercial demonstration of coal-to-liquid plants with carbon capture and storage is successful and the first commercial plants start up in 2020 and if it is

assumed that capacity will grow by two to three plants each year, coal-to-liquid fuels with CO2 life-cycle emissions similar to those of petroleum-based fuels can replace up to 3 million barrels of gasoline equivalent per day by 2035. That option would require an increase in U.S. coal production by 50 percent.

Finding S.19 (see Finding 7.2 in Chapter 7)

The deployment of alternative liquid transportation fuels aimed at diversifying the energy portfolio, improving energy security, and reducing the environmental footprint by 2035 would require aggressive large-scale demonstration in the next few years and strategic planning to optimize the use of coal and biomass to produce fuels and to integrate them into the transportation system. Given the magnitude of U.S. liquid-fuel consumption (14 million barrels of crude oil per day in the transportation sector) and the scale of current petroleum imports (about 56 percent of the petroleum used in the United States is imported), a business-as-usual approach is insufficient to address the need to find alternative liquid transportation fuels, particularly because development and demonstration of technology, construction of plants, and implementation of infrastructure require 10–20 years per cycle.

Recommendation S.13 (see Recommendation 7.8 in Chapter 7)