Liquid Transportation Fuels from Coal and Biomass: Technological Status, Costs, and Environmental Impacts (2009)

Chapter: 4 Thermochemical Conversion of Coal and Biomass

4

Thermochemical Conversion of Coal and Biomass

This chapter reviews the thermochemical conversion of coal, biomass, and combined coal and biomass to liquid transportation fuels. It addresses the questions raised in the statement of task related to the application of thermochemical conversion to the production of alternative liquid transportation fuels from those feedstocks by discussing the following:

-

The development status of each major technology with estimated times of commercial deployment.

-

Projected costs, performance, environmental impact, and barriers to deployment by 2020.

-

Potential supply capability, plant carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, and life-cycle greenhouse gas emissions.

-

Challenges and needs in research and development (R&D), including basic-research needs for the long term.

The available technologies are described first, and their status and technical and commercial readiness are assessed. Detailed cost and performance analysis, R&D and demonstration needs, environmental impacts, and analysis of greenhouse gas life-cycle emissions of the key technologies are discussed.

STATUS AND CHALLENGES OF TECHNOLOGY ALTERNATIVES

Thermochemical conversion involves either the gasification of biomass or coal followed by synthesis to liquid fuels (indirect liquefaction) or the direct conversion of coal to liquid fuels (direct liquefaction) with high-pressure hydrogen (H2), as shown in Figure 4.1. Those thermochemical conversion processes are considered to be ready for deployment between now and 2020. Because of its chemical complexity, biomass can also be converted to liquid fuels by pyrolysis or liquefaction. Those routes are not as well developed.

For each of the technologies, the panel has considered the technological readiness, costs, environmental impacts, characteristics of the finished products, and barriers to deployment. The panel also projected the potential commercial contribution that thermochemical conversion could make in the period 2020–2035 and beyond 2035.

FIGURE 4.1 Summary of thermochemical conversion processes discussed in this chapter.

Gasification Options

Processes that break the carbon-containing material down into gaseous products by gasification and then use those to produce liquid fuels are referred to as indirect processes to distinguish them from “direct” processes that break coal down into liquid products without going through gaseous intermediates.

For the indirect route of principal interest, solid feedstock is gasified by reacting it with sufficient oxygen to increase its temperature to a point where steam can react with the remaining carbonaceous material to produce syngas, a mixture of carbon monoxide (CO) and H2. Next, the syngas is cleaned to remove contaminants—such as particles, sulfur, ammonia, and mercury—and further processed to adjust the ratio of H2 to CO by using the water–gas shift reaction. The clean syngas is then used to make either a single product, such as fertilizer or methanol, or multiple products, such as fuels, H2, steam, and electric power.

Gasification has been used commercially around the world for nearly a century by the chemical, refining, and fertilizer industries and for more than 35 years by the electric-power industry. More than 420 gasifiers are in use in some 140 facilities worldwide, including 19 plants in the United States. Gasification technologies can also be used on the vast Canadian oil-sand deposits to gasify coke or bitumen to produce H2 and to produce a substitute natural gas from America’s abundant coal resources (Furimsky, 1998). The gasification process can convert combined feedstocks, such as coal and biomass, in the same gasifier at the same time. Thermochemical conversion would use nonfood biomass feedstocks—such as lignin, cellulose, and plastic wastes—and thus would not raise issues of competition between the markets for fuel and food.

Synthesis Options

Broadly speaking, two technologies for converting synthesis gas to liquid transportation fuels have been proved on a commercial scale:

-

Fischer-Tropsch (FT) technology. This technology was developed in Germany in the 1920s, and commercial plants constructed there in the middle 1930s were later used to produce transportation fuel in World War II. FT technology was commercialized in the South African Synthetic Oil Corporation (Sasol) complexes beginning in the middle 1950s. The process involves the catalytic conversion of the H2 and CO in synthesis gas into fuel-range hydrocarbons, such as diesel or gaso-

-

line, and naphtha and liquid petroleum gas (LPG). Sasol now produces transportation fuels from coal at the rate of more than 165,000 bbl/d.

-

Technologies based on methanol synthesis. Synthesis gas can also be converted to methanol with available commercial technology. The methanol can be used directly or can be upgraded into high-octane gasoline with a proprietary catalytic process developed by ExxonMobil and referred to as the methanol-to-gasoline (MTG) process. Methanol can also be converted to a mixture of gasoline and diesel with a variant of the MTG process called the methanol-to-olefins, gasoline, and diesel (MOGD) process.1 Methanol synthesis can also be the starting point for producing dimethyl ether (DME) and a broad array of other chemicals.

Direct-Liquefaction Technology

Direct liquefaction of coal involves a selective depolymerization of coal by breaking apart the coal structure into smaller units. The depolymerization is typically accomplished by thermal degradation of the coal with high temperatures and by simultaneous addition of hydrogen under high pressure. The hydrogen can be added from the gas phase or through hydrogen donation from suitable solvents in the presence of a catalyst. The direct-liquefaction procedures are carried out at about 450°C and at high pressures up to 30 megapascals (MPa). The product is a synthetic crude oil that can be refined into liquid transportation fuels. Commercial-scale direct liquefaction started in Germany in 1926; by 1939, production had reached more than 1 million tons a year. A commercial-scale plant was started up in the United Kingdom in 1935. In the 1970s, pilot plants were constructed in Japan and in the United States after the oil embargo. All those plants have been dismantled because of the collapse in world oil prices in the early 1980s.

Although direct liquefaction of coal has been demonstrated and is being scaled up in China, it is not ready for commercial deployment. Many questions associated with the design and operation of a direct coal-liquefaction plant require resolution. Most of the unresolved issues require process demonstration operations and then commercial demonstration. That would require a closely coupled R&D program to resolve issues and advance the technology. The panel does not deem

the technology ready for commercial deployment and estimates that an aggressive process and commercial demonstration program could make it ready for commercial deployment if it shows an advantage for commercial potential relative to other options for conversion of coal to clean transportation fuels.

Carbon Capture and Storage

During the conversion of coal and biomass to liquid fuels via direct or indirect liquefaction, large quantities of CO2 are produced. To minimize emission to the atmosphere, the CO2 must be captured and stored. CO2 from the off-gas streams of the conversion processes can be readily captured with commercially available technologies. Permanent geologic storage of the large quantities of CO2 that would be produced by a full-scale liquefaction industry appears feasible but has been demonstrated at only a few locations worldwide. Although carbon capture and storage are discussed in the context of the technical overview of indirect liquefaction in this chapter, the issues of feasibility and commercial readiness apply to both direct and indirect liquefaction of coal.

INDIRECT-LIQUEFACTION TECHNOLOGIES

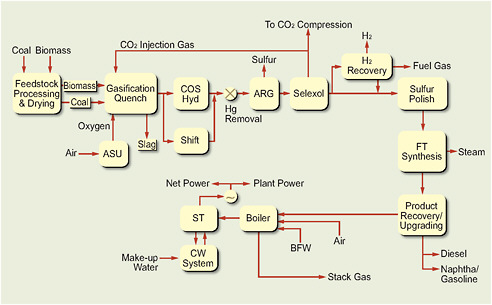

This section describes the overall indirect-liquefaction process that converts coal, biomass, or coal–biomass mixtures into liquid transportation fuels (Figure 4.2). Key elements of this process are gasification, syngas cleanup and conditioning, synthesis, and product upgrading. The process economics and greenhouse gas emissions of different options of indirect liquefaction are compared in a model analysis later in this chapter. The technical challenges and product characteristics are also discussed.

Process Technical Overview

Gasification involves creating a contact between a carbon-containing feed material and oxygen (or air) and steam at high temperatures to produce synthesis gas. The several basic gasifier designs are distinguished by the use of wet or dry feed, the use of air or oxygen, and the reactor’s flow direction (upflow, downflow, or circulating). Today’s pressurized entrained-flow coal gasifiers—such as those developed by General Electric, Conoco Phillips, Siemens, and Shell—can process feedstock at about 3000 tons/day. Biomass gasifiers have not generally been used to produce

FIGURE 4.2 Schematic of generic plant for indirect conversion of coal and/or biomass.

Source: Tomlinson and Gray, 2007.

synthesis gas. They are generally smaller and operate at lower pressures and tem-peratures than do coal gasifiers. Although there are many fixed-bed biomass gasifiers, fluid-bed and recirculating-bed systems have been developed.

A 3000 tons/day coal gasifier would produce enough synthesis gas to yield transportation fuel at about 6000 bbl/d by indirect liquefaction. After being ground into very small particles, the coal can be slurried with water or fed dry into the gasifier with a controlled amount of air or oxygen and steam. Temperatures in a gasifier range from 1400°F to 2800°F. At such high temperatures in the gasifier, steam reacts with the carbonaceous material of the feedstock to form syngas.

Coal Gasification

A number of technologies have been developed for coal gasification; they include moving-bed, fluid-bed, circulating-bed (transport), and entrained-flow gasifiers (MIT, 2007). The operating temperature and the size of coal feed vary with the type of gasifier. The moving-bed gasifier was developed by Lurgi and improved by Sasol. It operates at 425–600°C and accepts coal feed sizes of 6–50 mm. The

Sasol–Lurgi gasifier has been used extensively at the Sasol commercial plant in South Africa. Entrained-flow gasifiers operate at 1250–1600°C and accept coalfeed particles smaller than 100 μm. Those oxygen-blown, high-pressure gasifiers have been developed by General Electric (it was formerly referred to as the Texaco gasifier), Shell, Conoco Phillips (E-Gas), and Siemens (formerly referred to as the Future Energy gasifier). Fluid-bed gasifiers are less developed than the other two types. They operate at 900–1050°C and can use coal feed of 6–10 mm. In most types of gasifiers, avoiding soft ash particles is essential because the particles stick together, stick to process equipment, and typically lead to shutdown (MIT, 2007).

Coal gasification is commercially deployable today by using any one of several gasification systems that are being commercially used. Producing coal-to-liquid (CTL) fuels and other applications of gasification will lead to further improvements in the technology so that it would become more robust and efficient by 2020. Those improvements are part of the usual evolution of any new technology.

Coal and Biomass Gasification

Adding sustainably grown and harvested biomass to the coal feedstock would allow an increase in domestic fuel supply while reducing total greenhouse gas emissions in two ways. First, the emission of carbon in the burning of the fuels made from biomass is countered by the removal of carbon from the atmosphere by the biomass through photosynthesis during its growth. Second, the biomass and coal carbon that is converted to CO2 during the conversion to transportation fuels could be captured and stored.

The notion of gasifying mixtures of coal and biomass to produce liquid fuels is relatively new, and there has been little commercial experience. Many gasifiers can gasify biomass, but most of them are small in scale, use air instead of oxygen, and operate at lower temperatures and at low or atmospheric pressure. Under those less severe conditions, pyrolysis dominates, and the main products, in addition to syngas, are light hydrocarbons, bio-oils, tars, and char. Those products make such gasifiers less suitable for producing FT liquid fuels.

The NUON Shell 253-megawatt electric (253-MWe) integrated gasification combined-cycle (IGCC) facility in the Netherlands has proved that gasification of combined wood (30 percent by weight) and coal can be achieved for the generation of electric power. It has also gasified other biomass feedstocks, including chicken litter.

The operation of a combined coal-and-biomass-to-liquids (CBTL) plant would be similar to that of a CTL plant, except that biomass is gasified in addition to coal (Figure 4.2). Separate gasifiers could be used for the biomass and the coal, but it might be more efficient and cost-effective if the same gasifier could convert both feeds simultaneously. That would be similar to the situation at the NUON discussed above in which the Shell gasifier was able to gasify both wood and other biomass with the same lock-hopper high-pressure feeding system.

Combined coal and biomass gasification is deployable today, although the amount of biomass relative to coal feed is small, as discussed above. Further commercial development of the technology will make it more robust and efficient and enhance its ability to use higher fractions of biomass by 2020.

Biomass Gasification

Published data on high-pressure biomass gasifiers are sparse. Because of the fibrous nature of most biomass sources, the material is difficult to pretreat and feed into a high-pressure gasifier. Typical problems include clumping and bridging.

Biomass gasification exhibits many similarities to coal gasification, including the variety of gasifier types and different available approaches to gasification technology. However, the reaction conditions are generally milder than those for coal gasification because of the higher reactivity of biomass.

Gasification with direct firing with oxygen at higher pressures and temperatures produces a relatively pure syngas stream with small quantities of CO2 and other gases. For temperatures greater than 1000°C, little or no methane, higher hydrocarbons, or tar is present.

A major difference between biomass gasification and coal gasification is that the former generally involves smaller units than the latter because of the limits on the availability of biomass in a reasonable harvesting area. Biomass gasification therefore will not have the benefit of economies of scale that larger-scale coal gasification has. The lack of economies of scale will increase the cost per unit product of biomass gasification unless major process simplification and capital-cost reduction can be achieved. Like coal gasifiers, biomass gasifiers can be lumped into specific types, each of which has many variations.

Several U.S. and European organizations are developing advanced biomass gasification technologies, and about 10 biomass gasifiers have a capacity greater than 100 tons/day operating in the United States, Europe, and Japan (IEA, 2007; Cobb, 2007). Those units have a broad variety of feedstocks, feed capabilities,

characteristics, product-gas cleanup approaches, and primary products. The Biomass Technology Group lists more than 90 installations (most are small) and more than 60 suppliers of equipment that is used in gasification (Knoef, 2005). Although several of the available technologies have been commercially demonstrated, they have yet to be fully demonstrated commercially for integrated biomass gasification and transportation-fuel production. The panel considers biomass gasification to be technically ready for aggressive commercial demonstration but not yet well enough understood to ensure efficient, effective commercial deployment today. Many variations require understanding and improvement. With an aggressive commercial development program, biomass gasification technology could be ready for full-scale commercial deployment by 2015. The major issues to be resolved are related to engineering, particularly the extent of biomass pretreatment necessary and effective feeding of biomass to high-pressure gasification reactors. An example of the conversion of biomass into liquid transportation fuels is the partnership of Choren Industries and Shell. Choren provides the Carbo V gasification process, and Shell provides the FT synthesis technology.

Most of the gasification technologies present technical or operational challenges, most of which can probably be resolved or managed with commercial experience. Gasifier choice depends on the type of biomass feed and on the specific application of the gasification or pyrolysis products. The gasifier units will generally be smaller than large-scale coal gasifiers because of the economics and logistics of the feed supply. The most persistent problem appears to be related to biomass feeding, processing, and handling, particularly if a gasifier has to contend with different biomass feeds.

Syngas Cleanup and Conditioning

The raw syngas produced in the gasification of coal and biomass contains many impurities, such as CO2, hydrogen sulfide, carbonyl sulfide, ammonia, chlorine, mercury, and other toxic chemicals. Biomass has much lower sulfur content than coal does, and sulfur impurities in the syngas are correspondingly lower. However, biomass ash can contain high concentrations of sodium, potassium, and silicon that might pose additional requirements for the cleanup system. The impurities have to be removed before the syngas is allowed to contact the synthesis catalysts; otherwise, catalyst poisoning and deactivation will result. For example, in the conceptual configuration shown in Figure 4.2, carbonyl sulfide is hydrolyzed to hydrogen sulfide. Ammonia is scrubbed out and mercury is removed with acti-

vated carbon, and CO2 and hydrogen sulfide are removed with Selexol or another acid-gas removal system. The processes for removing the contaminants are all commercially available.

In addition to cleaning, the H2:CO ratio is adjusted to be compatible with the synthesis process by using the water–gas shift process. In this process, CO is converted by reaction with steam to H2 and CO2. The CO2 can then be removed in the acid–gas removal system to produce a concentrated stream of CO2 that is suitable for storage. The same is true for biochemical conversion of biomass to ethanol. The fermentation step produces a stream of pure CO2 that can be compressed and geologically stored. The transport and storage costs will be somewhat higher because the amount of CO2 will typically be smaller for the biochemical conversion route than for a thermochemical conversion route with an equal biomass feed rate. Because synthesis catalysts are readily poisoned by minute quantities of sulfur, a polishing reactor that removes sulfur down to parts per billion is included before the synthesis reactor. Ultimately, the hydrogen and carbonyl sulfides are converted (99.99 percent) to elemental sulfur, and the mercury is removed.

Syngas cleanup and conditioning technology is ready for full-scale commercial deployment today. It will undergo substantial improvement as a result of normal process evolution and become more robust and efficient by 2020.

Synthesis

Once the syngas produced by gasification of the carbonaceous feed has been cleaned of impurities and shifted to the desired H2:CO ratio, it can be used to synthesize liquid transportation fuels. Two major commercial synthesis processes can be used to produce transportation fuels, such as gasoline, diesel, and jet fuel. These are FT and methanol synthesis followed by MTG. DME can also be produced by dehydration of methanol, but it is not a liquid fuel under ambient conditions. DME is discussed in Chapter 9.

Fischer-Tropsch Synthesis

The clean synthesis gas is sent to FT reactors, where most of the clean gas is converted into zero-sulfur liquid hydrocarbon fuels. If the major required product is distillate or diesel boiling-range fractions, slurry-phase reactors are used. One of the limitations of FT synthesis is that it produces a wide array of hydrocarbon products in addition to some oxygenates. The array of products depends on the

probability of chain growth relative to chain termination. The probability function can theoretically be modeled with the Schultz–Flory–Anderson relationship, in which the parameter alpha determines the shape of the probability curve; the higher the alpha, the longer the hydrocarbon chains. To maximize liquid products in the naphtha and diesel boiling range, it is best to produce waxes first and then to crack the wax selectively to lower-boiling-point materials.

The low-temperature FT process produces about 10 percent hydrocarbon gases, 25 percent liquid naphtha, 22 percent distillate, and 46 percent wax and heavy oil. The wax can then be selectively hydrocracked into distillate. With this approach, the overall product distribution can be skewed in favor of diesel. The clean fuels are recovered, and the wax is hydrocracked into more diesel fuel and naphtha. The naphtha can be upgraded into gasoline, but substantial refining is necessary to produce high-octane material because of the paraffinic nature of naphtha. The CO2 in the FT tail gas is removed for storage, and the remaining synthesis gas is returned to the FT reactors for additional liquid production.

The FT process has been used for decades by Sasol and involves reacting synthesis gas over metal-based catalysts to yield a variety of hydrocarbons that can be converted to high-quality transportation fuels (gasoline, diesel, and jet fuel). The first such plant, known as Sasol I, used a combination of fixed-bed and circulating-fluid-bed FT reactors to produce the fuels. Recently, the Sasol I plant changed from coal to natural gas as feedstock, and it is now a gas-to-liquid (GTL) plant. In the early 1980s, Sasol built two large FT-based indirect coal-liquefaction facilities that together produce transportation fuels at over 160,000 bbl/d. The plants were designated Sasol II and III. Twenty years later, the plants are profitable, but they received government subsidies for several years after start-up. They would not have been economically viable in a market economy with relatively cheap oil and without government assistance.

FT synthesis is continuously being improved; since the building of the large Sasol plants, there have been substantial advances both in coal-gasification technologies that produce synthesis gas and in FT technology that produces clean fuels. The Sasol II and III plants originally used circulating-fluid-bed synthol reactors, which were later replaced by fixed-fluid-bed Sasol advanced synthol reactors. These are less expensive, are easier to operate, and have a much greater fuel-production capacity than synthol reactors. Research and development (R&D) at Sasol started experimenting with slurry-phase FT reactors in the early 1980s and built a 2,500-bbl/d prototype reactor at Sasol I to demonstrate and develop the technology. These reactors, which have operated on both iron and cobalt FT cata-

lysts, formed the basis for the huge slurry reactors that have been installed at the Oryx GTL plant in Qatar. The slurry reactors, with a diameter of about 36 ft, are each capable of producing fuels at 17,000 bbl/d.

Other companies are also developing FT reactor technology. Shell has developed the fixed-bed FT process known as the Shell middle-distillate synthesis process. Its GTL plant in Bintulu has been operating since the late 1980s, and recent improvements in the reactors and catalysts have increased the fuel-production rate substantially. ExxonMobil has developed a slurry-bed FT process with a patented cobalt-catalyst system that was the basis of its Qatar GTL plant design. The company withdrew that project from consideration in 2007 in favor of a liquefied-natural-gas plant. Conoco Phillips also has developed a FT system that was demonstrated on a pilot scale in Oklahoma. Syntroleum, another U.S. company, has also developed a somewhat different FT process for its GTL system. It has produced sufficient quantities of FT jet fuel for testing by the U.S. Air Force. The U.S. company Rentech has been developing an FT technology based on a slurry-bed reactor for a number of years and has recently built a pilot facility in Colorado. Other experimental FT systems are under development, including a microchannel reactor being tested by Velocys.

No commercial plant that combines advanced2 coal gasification with advanced FT technologies has been built. The only operating commercial-scale indirect CTL plants in the world are the Sasol plants. China—a country with increasing consumption of liquid fuels, a scarcity of domestic petroleum, and large coal resources—is moving rapidly toward commercialization of CTL technologies. The Shenhua direct-liquefaction process in Inner Mongolia launched its first trial operation of fuel production in December 2008.

FT synthesis technology can be considered commercially deployable today. Like several other ready-to-deploy technologies, it will undergo substantial process improvement by 2020, which will lead to more robust and efficient technology for producing liquid transportation fuels.

Methanol Synthesis and Conversion to Gasoline

The other major indirect liquefaction route involves the synthesis of methanol and its conversion to liquid transportation fuels. Methanol synthesis is a large-scale, commercial technology that can be supplied by several license holders and is used commercially to produce methanol from coal. It is well developed, is highly selective, and is used primarily to convert synthesis gas made from natural gas. The largest methanol plants can each produce about 5000 tons/day. Methanol is a feedstock for the manufacture of many chemicals and can be used as a fuel itself. Because of the ubiquity of methanol manufacture (Kung, 1980), that process is not discussed in detail here.

The MTG technology developed by Mobil Oil Corporation was demonstrated in a commercial plant in New Zealand (S. Tabak, ExxonMobil Research and Engineering Company, presentation to the panel on February 19, 2008). MTG technology produces mainly high-octane gasoline. A variant of MTG involves the conversion of methanol to olefins and their conversion to gasoline and diesel fuel and is referred to as MOGD. It has not been demonstrated commercially.

The key to the MTG process was the development of shape-selective zeolite catalysts that produce hydrocarbon molecules in the gasoline size range. The principal product is high-octane gasoline, and the secondary product is LPG. A plant with a capacity of 14,500 bbl/d was started in 1985 in New Zealand. It used natural gas as the feedstock and operated successfully for about 10 years. The drop in crude-oil and gasoline prices at the time resulted in curtailment of gasoline production and conversion of the plant to production of chemical-grade methanol. However, the improvements learned from the commercial operation in New Zealand are being incorporated into a second-generation plant under construction in Shanxi, China, by Jincheng Anthracite Coal Mining Company. The plant will feed coal-derived methanol and was scheduled to start in late 2008. The process uses gas-phase conventional fixed-bed reactors. A coal-to-fuels project in the United States is also planning to use MTG: a small-scale plant is under development by Consol Energy and Synthesis Energy Systems to convert West Virginia coal into gasoline at about 6000 bbl/d with the U-GAS® process followed by MTG. The development of that plant, however, was on hold in 2008 because of unfavorable economic conditions.

Figure 4.3 shows the schematic flow diagram of the New Zealand natural-gas-to-gasoline complex (Tomlinson et al., 1989), which converts methanol to 38.7 percent gasoline, 0.7 percent fuel gas, 4.6 percent LPG, and 56 percent water

FIGURE 4.3 Schematic of New Zealand MTG complex.

Source: Adapted from Tomlinson et al., 1989.

by weight. The water is recycled as process water. Gasoline produced by the process is completely compatible with the conventional gasoline infrastructure, and it contains zero sulfur and is low in benzene (Tomlinson et al., 1989).

The panel considers standard MTG technology to be commercially deployable today, and, as indicated above, several projects are moving toward commercial deployment. Several variations of the technology are ready for commercial demonstration and could provide improvements in the standard MTG technology. They will evolve with commercial application and become more robust and efficient by 2020.

Challenges and Barriers to Deployment

Because the nation has more than 250 billion tons of recoverable coal reserves and because there is a considerable potential to provide large quantities of biomass, there is an opportunity to use the technologies described above to enhance U.S. energy security by producing clean, fungible transportation fuels to supplement the conventional petroleum supply. In spite of the large quantity of coal and continued high oil prices, there were no coal-liquefaction plants in the United

States in 2008, but several potential plants are in the development phase. This section discusses the environmental, economic, commercial, and social barriers to deployment.

The key components of CTL fuel technology have been commercially demonstrated and are ready for commercial deployment. However, from a technical and engineering standpoint, the integration of advanced entrained coal-gasification technologies, an advanced syngas cleanup process, and advanced slurry-phase FT synthesis technologies has never been demonstrated on the scale of a large synthetic liquid-fuel plant. The lack of experience poses a degree of technical risk that would be considered unacceptable by potential process developers and project funders. The panel believes that the technical barriers will be substantially reduced as soon as several first-mover plants become operational. The financial barriers will still be of concern because of the potential high variability of the energy markets. The technology is expected to evolve and improve with commercial experience and to become more robust and efficient.

Because of concerns about global climate change and greenhouse gas emissions, another major technical barrier is the demonstration that captured CO2 can be stored in geologic formations for extended periods in a safe, effective, and efficient manner. Resolving issues of potential long-term leakage and safety will require an aggressive program to demonstrate geologic storage and to develop data and procedures related to evaluation, permitting, injection, monitoring, and closure. That will also be needed to gain the political and popular support required to make geologic storage ready for multiple commercial deployments. The current status of the technology and the desired work remaining suggest that it will not be commercially deployable on a broad scale before 2015. Ideally, funds and programs for the design, construction, and operation of three commercial demonstrations of geologic storage in different geologic formations focused on gaining the CO2 storage information outlined above will be available soon. Such programs could be linked to indirect-liquefaction plants that use advanced technologies or coal-based power plants as total commercial demonstration of technologies with integrated carbon capture and storage (CCS). Two of the integrated facilities would be fed by coal of different rank and one by coal and biomass. One or two of the facilities could be operated to demonstrate geologic CO2 storage independently if integration of generation and storage causes a substantial delay in the demonstration of geologic storage.

Carbon Capture and Storage

The central issue in using coal in a carbon-constrained world is its inherently low ratio of hydrogen to carbon, which results in large CO2 emissions. Unless the resulting CO2 is captured during conversion and stored permanently (underground or by incorporating it in some other product), the life-cycle greenhouse gas emissions in converting coal to liquid fuels are about twice as great as those in producing and using fuels based on petroleum (Jaramillo et al., 2008; Bartis et al., 2008). Therefore, use of coal to produce liquid fuels in quantities needed to substitute for transportation fuels will require developing and demonstrating CCS on a large scale, which involves efficient and economic capture of CO2 and safe and efficient geologic storage. Demonstrating “the technical, economic, and environmental performance of the technologies that make up all of the major components of a large-scale integrated CCS project” (MIT, 2007, p. xi) will take billion-dollar investments by industry and government and could take a decade. Therefore, it is critical to start those demonstrations, with research involving multiple fully integrated monitoring and data-gathering activities, immediately (MIT, 2007). To date, few demonstrations of geologic storage of CO2 have been carried out on the needed scale. Governments and private companies have been hesitant to make the necessary investment that would ensure that the United States has a robust set of technologies that could be used for its energy future in the absence of any clear CO2-management policy. Without policy, there are no strong drivers, and the economics are negative.

Carbon dioxide capture is commercially deployable technology. Such processes as Selexol, Rectisol, and amine scrubbing are common in the petroleum and chemical industries. In indirect liquefaction, carbon dioxide is removed from the synthesis gas before production of liquid fuels, so the production of a concentrated stream of CO2 is an integral part of the processes. The concentrated CO2 stream can then be dehydrated and compressed for storage. Thus, it is possible to demonstrate any of several coal or coal–biomass processes commercially and to produce a concentrated CO2 stream for geologic storage with little impact on the cost of the liquid fuels produced.

Several projects are injecting megatonne quantities of CO2 each year into geologic formations, and no problems have been observed; but none of the projects is in the United States. Demonstrations in the United States that address the issues peculiar to the country and that are well planned and monitored are needed. In Norway, at the Sleipner Field in the North Sea, more than 1 million

tonnes of CO2 per year has been injected into a deep saline aquifer for more than a decade with no identifiable problems. The FutureGen program of the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) intended to demonstrate CCS, but it was abandoned in 2007 when the estimated price doubled unexpectedly. However, DOE Regional Partnership projects to demonstrate larger-scale CO2 storage in various geologic formations are under way. Those projects need to be increased to true commercial size and moved forward much more rapidly if geologic storage is to be adequately demonstrated so that it can be used to store CO2 captured from coal plants in the needed timeframe. The government of the United Kingdom just announced a plan to carry out a demonstration on its soil, according to news accounts (Lovell, 2008), but has not taken steps beyond the announcement.

In the technical scenarios that are compared earlier in this chapter, the panel assumes that CO2 capture uses state-of-the-art technology, such as would be used in conventional refining and IGCC power plants. Such processes as Selexol, Rectisol, and amine scrubbing would be used. The processes considered produce a concentrated stream of CO2 as an integral part, so CO2 storage can be readily and more cheaply achievable. CO2 transport by pipeline is a well-demonstrated technology; such CO2 is used in enhanced oil-recovery (EOR) operations at about 35 million tons/year. Pipelining of CO2 poses no technical issues, but permitting issues are associated with obtaining rights-of-way, as is the case with most infrastructure projects. However, the technical and legal issues associated with the storage of captured CO2 still need to be clarified and resolved.

The estimates of potential costs of CCS in an earlier section are “bottom-up” and are based largely on engineering estimates of expense for transport, land purchase, permitting, drilling, all required capital equipment, storing, capping wells, and monitoring for an additional 50 years. However, experience suggests that the full cost of storage might not be captured by such an approach in light of barriers to implementation that increase cost. Uncertainties in the regulatory environment arising from concerns of the general public and policy makers are likely to evolve under the influence of future events (Palmgren et al., 2004). It is difficult to estimate such costs without some commercial-scale geologic storage experience, as outlined above. A reliable estimate of future cost of storage would contain, at least qualitatively, the uncertainty arising from such factors. Accordingly, quantified costs based on engineering analysis would probably represent a lower bound on future costs. (See Appendix K for a more detailed discussion.)

If liquid fuels produced by thermochemical conversion of coal or coal and biomass with CCS are to meet a sizable portion of U.S. demand for transporta-

tion fuels, more than a gigatonne of CO2 captured from such processes would have to be stored each year. CO2 capture and transport entail a potential health risk associated with acute leaks and with exposure of workers or populations to hazardous concentrations of CO2 near facilities. Geologic storage has the potential of an ecological risk to soils and groundwater as a result of chronic leakage and a warming risk associated with either sudden or chronic leaks that might partially or entirely vitiate the climatic value of a storage site (Anderson and Newell, 2004; Socolow, 2005). The public and policy makers are likely to anticipate those risks and require that they be taken into account in the design, monitoring, and carbon-accounting procedures and associated regulatory frameworks that would be part and parcel to storage (Wilson et al., 2007). As a result, timing estimates need to recognize the potential for delay in initiating demonstration projects because of lags in conception and development of the overall regulatory regime for storage and in licensing of each specific project, both in the demonstration phase and beyond. Some issues, such as liability insurance for near-term operation and long-term site maintenance, require political resolution that could introduce additional delays (IRGC, 2008). Uncertainty over the likelihood of long-term leaks could translate into regulations that require the sources that plan to store carbon to purchase allowances equivalent to fractions of the carbon stored. Such a requirement would increase the net cost of CCS. All those issues need to be evaluated as part of the several geologic-storage demonstration projects mentioned above to provide the best information for the evaluation of future commercial activities.

Once CCS attains full commercial-scale operation, delays could arise because of accidents that cause or threaten releases. Because the technologies, monitoring, and regulation of storage are likely to be closely related, if not identical among sites, interruption of operations at one site could affect operations at other sites; broadly reduce or temporarily eliminate storage; undermine the credibility of the technology among investors, regulators, policy makers, and the general population; and add a substantial risk premium to investment in CCS. Continuous storage operations might be subject to multiple regulatory regimes (and varied siting, licensing, and monitoring requirements) at various government levels. Those issues and potential causes of delay apply to other major commercial operations, including production, pipelining, and refining of crude oil.

CO2 is being used for EOR at the Weyburn oil field in Canada; CO2 from the Great Plains lignite gasification plant is used at almost 1 million tons/year. Statoil has been successfully injecting CO2 from the Sleipner gas field into the Utsira Formation, a deep saline aquifer, at more than 1 million tonnes/year for over a decade.

CO2 is also being reinjected at the Salah liquefied-natural-gas (LNG) project in Algeria at about 1 million tonnes/year. There has been no indication of problems arising from any of those projects, and the CO2 storage shows no sign of leakage.

EOR can present an opportunity for early CCS and can reduce the cost of CCS by providing a net return. Use of CO2 in EOR has been safe and has not raised any questions about the ability to store CO2 in proper geological formations safely over the long term. EOR in the United States uses CO2 at 35–40 million tonnes/year. There are opportunities for additional EOR, but those storages are small compared with the large amounts of CO2 that would be captured if CTL becomes widely deployed, potentially in the gigatonnes-per-year range. CO2 could be stored in deep coal seams, where it can displace methane for use in the natural-gas pipeline. CO2 binds more strongly to coal than does methane and thus replaces it; and just as the methane is permanently locked in the coal seam for extremely long times, the CO2 will be permanently stored there. Again, however, the use of CO2 in coal-bed displacement is small in relation to the total amounts that need to be stored.

With adequate demonstration and long-term monitoring, CCS could offer a way to use the nation’s wealth of fossil fuel while limiting adverse effects on climate. What is now needed is aggressive demonstration on a commercial scale in several U.S. geologic formations to develop the needed data and to understand and resolve issues.

Supply of Feedstock

Deployment of such facilities will require the use of large quantities of coal and thus an expansion of the coal-mining industry. For example, a 50,000-bbl/d plant will use about 7 million tons of coal per year, and 100 such plants producing liquid transportation fuels at 5 million bbl/yr would require about 700 million tons of coal per year—a 70 percent increase in coal consumption. That would require major increases in coal mining and transportation infrastructure to move coal to the plants and fuel from the plants to the market. Those issues could pose major challenges, but they could be overcome.

The next question is whether sufficient coal is available in the United States to support such increased use. The National Research Council evaluated domestic coal resources (NRC, 2007) and concluded:

Federal policy makers require accurate and complete estimates of national coal reserves to formulate coherent national energy policies. Despite significant uncertainties in existing

reserve estimates, it is clear that there is sufficient coal at current rates of production to meet anticipated needs through 2030. Further into the future, there is probably sufficient coal to meet the nation’s needs for more than 100 years at current rates of consumption. … A combination of increased rates of production with more detailed reserve analyses that take into account location, quality, recoverability, and transportation issues may substantially reduce the number of years of supply. Future policy will continue to be developed in the absence of accurate estimates until more detailed reserve analyses—which take into account the full suite of geographical, geological, economic, legal, and environmental characteristics—are completed.

The Energy Information Administration (EIA) recently estimated the proven U.S. coal reserves to be about 260 billion tons (EIA, 2009). A key conclusion of the NRC and EIA studies is that there are sufficient coal reserves in the United States to meet the nation’s needs for more than 100 years at current rates of consumption. Even with increased rates of consumption, ramped up over time, the reserves could support our needs for 100 years. The primary issue probably is not the reserves but the increase in mining of coal and the opening of many new mines. Increased mining has numerous environmental effects that will need to be dealt with in an environmentally acceptable way. Public opposition to increased coal mining is to be expected because of the need to open new mines and the environmental implications of mining more coal. Increasing coal use will undoubtedly increase the cost of coal, but coal costs are relatively low, and substantial amounts of coal can probably be produced at current or slightly higher prices.

A particular barrier to the establishment of biomass-to-liquids (BTL) plants is the availability of sufficient quantities of feedstock in a reasonable area. Because only small quantities of biomass (3000 tons/day) can be gathered, such plants will be limited in size by feedstock constraints. That leads to small-scale plants and hence diseconomies of scale and high capital cost. Another challenge is the successful feeding of raw biomass to high-pressure gasification systems. Biomass, unlike coal, is soft and fibrous and difficult to reduce to the small sizes necessary for gasification. A third challenge is to reduce the high costs of biomass feed, including the costs of growing, harvesting, and transportation to the conversion plant. Biomass has very low energy density when raw, so transportation costs are high compared with the cost of coal, which is high in energy density.

Efforts to increase the energy density of raw biomass by pyrolysis are under way. Lurgi and Air Liquide have an interesting concept for conversion of low-energy-density biomass to liquid fuels. Biomass, such as switchgrass or woody biomass, is pyrolized in a double-screw retort with hot sand as the heat-transfer medium. The biomass degrades to form pyrolysis oil and char. The pyrolysis

oil and char are mixed together to form a “bio-syncrude,” which has an energy density 13 times that of the unprocessed biomass and contains 80 percent of the energy in the biomass. The bio-syncrude can be readily transported and fed to the Lurgi multipurpose gasification (MPG) process or other gasification processes to produce syngas, which can then be cleaned and used to synthesize liquid transportation fuels by FT. The concept appears to overcome the problems of transporting low-energy-density raw biomass and feeding raw or pretreated biomass to high-pressure gasification. The initial pyrolysis could conceivably be done on a field scale, and the high-energy-density bio-syncrude could be shipped to a central gasification facility for production of transportation fuels.

Economics and Investment

The uncertainty of future oil prices is an important barrier to deployment of CTL, as is the high capital expenditure needed for commercial CTL plants. A 50,000-bbl/d plant could cost $4–5 billion, so the plants could be expected to approach $100,000 per daily barrel, which is about 6 times as high as deepwater Gulf of Mexico crude-oil capital investment costs. The investment risk for such a large expenditure is considerable. In that context, it should be noted again that biorefineries for converting cellulosic biomass to ethanol have an estimated capital cost of about $120,000 per daily barrel of gasoline equivalent and that about 30 biorefineries (with production capacity of 40 million gallons of ethanol per year) are required for a 50,000-bbl/d output.

Infrastructure and Labor

If many plants are built worldwide at the same time, there will be competition for critical process equipment and engineering and labor skills. On the basis of parallels with the indirect-liquefaction industry, the timeline for commercial deployment in the United States would be long. Permitting and the usual public reluctance to accept the need for new facilities, especially coal-based plants, are issues. The proposed FT plant for conversion of anthracite residue to clean diesel fuel, to be built in Gilberton, Pennsylvania, has been in gestation for 12 years, and construction apparently has yet to begin. The Dakota gasification plant (which produces substitute natural gas from lignite) in Beulah, North Dakota, was originally proposed in the late 1960s and came on line in the early 1980s—a time span of some 12–15 years. Even if permitting and other legal issues do not impose a delay, it would still take at least 6 years to construct an indirect-liquefaction plant.

For example, the Sasol II and III complexes in South Africa required 6 years to construct from the time the South African government approved the plans.

Technology Forecast

Technologies Deployable in 2008–2020

The discussion above is related to technologies that are deployable now or potentially deployable in the near future. CTL plants that use gasification followed by FT or MTG synthesis can be built today. Although integration of advanced entrained coal gasification with FT has not been commercially demonstrated, the technical risk associated with such a venture is low because of the separate experience with commercial gasification for other applications and commercial use of FT in CTL and GTL processes. Because of the challenges listed above and the long lead time required for planning, detailed design, permitting, and construction, it is unlikely that any CTL plants will be in commercial operation in the United States before the 2015–2020 timeframe. CTL plants with CCS will probably take longer to be commercialized because of the need for commercial demonstration of carbon dioxide storage and monitoring before it can be applied broadly in commercial operation.

With some additional R&D focused on biomass pretreatment and feeding to gasification reactors, CBTL plants that coprocess small amounts of biomass (up to 30 weight percent) could be deployed today. Their rate of deployment would be subject to the same restrictions as the rate of deployment of CTL plants, and there is the additional issue of biomass availability and suitable plant site location. With the benefit of successful biomass pretreatment, small-scale thermochemical BTL plants using current biomass gasification and FT or MTG technology could also be deployed today.

With respect to deployment of future technologies, the panel’s review of the thermochemical-conversion technologies has separated them into two groups: those likely to be deployable in 2020–2035 and those requiring longer-term R&D.

Technologies Likely to Be Deployable in 2020–2035

Continued advances in both coal and biomass gasification technologies after 2020 are likely. For example, Pratt and Whitney Rocketdyne is developing a compact gasifier based on rocket-engine technology that, if proved successful, could reduce costs and improve efficiencies. The production of synthesis gas is the most capital-

intensive section of a thermochemical conversion plant, so cost reductions in that component would greatly improve overall economics.

As long as industrial interest in alternative fuels continues, the synthesis process—whether FT, MTG, or MOGD—is likely to undergo continuing improvement. For example, Velocys is developing a microchannel FT process that could improve synthesis gas conversion and reduce costs. With continued emphasis on climate change, successful demonstration and practice of CCS is likely to be attained, greatly accelerating the ability to deploy thermochemical fuel plants with safe CCS.

Another option for the conversion of syngas to liquids, other than FT, is catalysis (Chu et al., 1995; Herman, 2000). Syngas can be converted catalytically through the chain-growing process to such higher alcohols as isobutanol in a slurry-phase reactor. Better catalysts and reactor design are needed to improve the yield and selectivity of the catalytic conversion of syngas to higher alcohols (Herman, 2000; Li et al., 2005). The development and deployment of improved syngas cleanup, including reduction of hydrogen sulfide to parts-per-billion concentrations, are required to minimize catalyst poisoning. Then, the technology needs to be demonstrated on a semi-work scale for commercial deployment.

A novel approach that has potential for commercialization is chemical-looping gasification. In that process, a metal oxide is used as an oxygen carrier and is itself reduced to metal. The metal can then be reacted with steam to produce hydrogen and/or carbon monoxide, which can then be used to produce liquid fuels, chemicals, and electricity (Fan and Iyer, 2006; Fan and Li, 2007; Gupta et al., 2007). An example is the syngas chemical-looping process that has the potential to convert coal to hydrogen at 7–10 percent higher efficiency than conventional coal-to-hydrogen processes (Gupta et al., 2007). Furthermore, the syngas chemical-looping scheme can be integrated into the conventional CTL process (Gupta et al., 2007; Tomlinson and Gray, 2007), allowing the by-products of liquid-fuel synthesis to be converted to hydrogen. Such integration can lead to a 10 percent increase in liquid-fuel yield and a 19 percent decrease in carbon emission (Tomlinson and Gray, 2007). The full operability of the new process needs to be tested on a pilot scale. The feasibility of the technology will then have to be shown in a demonstration plant for later commercial deployment.

Combining technologies in a plant could result in improvements in the product slate, reductions in greenhouse gas emissions, or other benefits compared with a plant that uses a single technology. For example, it is well known that indirect liquefaction with FT produces an excellent high-cetane diesel fuel, but FT naphtha

is not well suited for gasoline. In contrast, the MTG process produces a high-octane gasoline with very high selectivity. Therefore, one might envision a plant in which syngas is split between FT and MTG to obtain the best of both: high-quality gasoline and diesel. Another example is potential reduction in greenhouse gas emissions through use of nuclear process heat as the source of process heat for thermochemical conversion of coal, biomass, or combined coal and biomass. Coupling a nuclear power plant with a synthetic-liquid-fuel facility could have, as one benefit, the elimination of greenhouse gas emissions from furnaces and other heaters throughout the synthetic-fuel production side of the plant.

Technologies Likely to Be Deployable After 2035

Technologies presented in this section are ones for which substantial R&D effort is still needed, but they could potentially provide drastic improvement to thermochemical conversion. Those technologies will probably not be realized until after 2035. Despite many apparent differences among process strategies, virtually all processes for thermochemical conversion of biomass and coal have several characteristics in common. They rely on the thermal breakdown of the feedstock (typically at 350°C or above) to produce a population of free-radical intermediates that undergo a complex sequence of reactions, they tend to produce a mixture of products rather than showing high selectivity to a single desired product, and they yield 2 ± 0.5 bbl of liquid product per ton of feedstock.

Technological developments that are beyond incremental improvements will probably have to be based on different ways of breaking apart the macro-molecules in the feedstock rather than relying on thermally driven bond-breaking. There are several potential developments. One is changing the reaction intermediates from radicals to positively charged carbon atoms (carbocations); this could be done with Lewis acid catalysts, for example. Consolidation Coal Company has investigated the direct liquefaction of coal in molten zinc chloride and reported high selectivities to gasoline. A second is enzymatic bond cleavage with fungi, bacteria, or other organisms engineered to have enzymes with high activity and selectivity for cleavage of particular kinds of bonds. A third is the application of energy to cleave bonds in much more targeted fashion with, for example, microwave heating or ultrafast (femtosecond) lasers tuned to specific bonds.

A major step forward will need to be based on a thorough understanding of the molecular structures of the feedstocks and of the specific kinds of bonds to be broken. The molecular features of coal, in particular, are not well understood and are thought to vary from one kind of coal to another.

Pennsylvania State University has developed two approaches for introducing coal or coal extracts into oil refineries (Clifford and Schobert, 2007). One involves extraction of coal with a petroleum solvent, such as light-cycle oil, followed by two-stage hydrotreating of the extract mixture. Fractionation after hydrotreating provides mainly clean jet fuel and diesel as products and smaller amounts of gasoline and heating oil. The second approach blends coal with the feed to delayed cokers. The coker liquid is mainly in the fuel-oil range with smaller amounts of lighter distillates. The university has licensed the technology to CoalStar Industries, Johnstown, Pennsylvania. CoalStar Industries is planning to build a 10,000-bbl/d demonstration and is in the final stage of selecting a site for the plant, which will probably be in southwestern Pennsylvania (D. Fyock, CoalStar Industries, personal communication, November 6, 2008).

Research, Development, and Demonstration

If the goal is to increase production of domestic liquid transportation fuels in the next several decades to enhance energy security, it is important to rapidly advance technologies that are commercially deployable today if their economics justify the deployment. Those first movers would need to have an associated applied R&D program to ensure success and to develop learning. An R&D program that addresses step-out technology improvements and developments and that develops new technologies also needs to be supported. Engaging in a new research program on the assumption that it will provide energy solutions in the near to middle term is unwise.

For thermochemical technologies that are deployable now, the financing hurdle remains serious primarily because of the volatility of the energy markets; but deployment is also affected by uncertainties in climate-change policy and by lack of full-scale commercial demonstration. The energy market’s uncertainty is illustrated by the price of crude oil over the last 3 years and its decrease from a high of $147/bbl to a low of $32/bbl in 5 months. The projects in question have a multiyear timeline from planning to operation, and they require capital of $1–5 billion or more. They face what has often been referred to as a valley of death in getting from development and demonstration to commercial deployment. Reaching commercial deployment will probably require a number of commercial first-mover projects combined with geologic storage of CO2 to gain commercial experience and to move the technology to robustness and to substantial cost reductions for the Nth plant, where N is a small number. The commercial first-mover proj-

ects would include a major R&D component to focus on solving problems and to develop technology for specific improvements. That would improve the technologies, quantify their relative costs, and reduce the risk associated with their commercial deployment if they show economic competitiveness. The panel considers this phase critically important for facilitating commercial deployment of thermochemical technologies.

An R&D program should be associated with commercial-scale demonstrations of geologic CO2 storage. The demonstrations need to involve detailed geologic research and a broad array of monitoring tools and techniques before initiation, as they proceed, and after they are closed to provide the understanding and data on which future commercial projects will depend. Because of the scale of geologic storage, research and monitoring need to be continued at a steady rate, after the demonstration projects are declared completed. Increased research efforts on the coal-mining end of the value chain are also warranted to improve understanding of the immediate and longer-term environmental effects of increased coal mining and use.

On the gasification and gas-treatment side, the current research program focuses on broadly applicable improvements. Continuation of that program would provide improved coal pumps, ion-transport membranes for oxygen separation, membranes for other separations, and various other technology improvements.

New catalysts and catalytic routes to liquid transportation fuels need continued study because those step-out technologies offer much potential. Likewise, new reactor concepts or separation concepts offer much potential. As new ideas come along, they need to be evaluated and their economic potential analyzed. The section “Technologies Likely to Be Deployable After 2035” above contains a number of new process concepts that require focused R&D. The ones that meet needs can be advanced to the process-demonstration stage to obtain data for evaluating commercial potential.

Costs and Performance

Between now and 2020, technologies for the thermochemical conversion of coal, biomass, and coal–biomass mixtures by gasification followed by FT synthesis or methanol synthesis followed by an MTG process will probably be commercially deployed in the United States and in other countries that have large coal resources, such as China, Russia, India, and Australia. To reduce the CO2 footprint of CTL plants, CCS technologies will have to be used. Capture of CO2 from CTL plants

uses the same state-of-the-art technology used in conventional refining, natural-gas processing, and IGCC facilities—for example, Selexol, Rectisol, and amine scrubbing. CTL plant configurations produce a concentrated stream of CO2 as an integral part of the process, so CO2 capture can be readily and more cheaply achievable than, for example, in IGCC or pulverized-coal plants. The higher cost of CO2 avoided3 with IGCC is a result of the fact that an IGCC plant without CCS would use a different configuration from one with CCS. An IGCC plant without CCS does not have water–gas shift and does not separate CO2 in the gasification–purification train. In contrast, water–gas shift and CO2-separation equipment has to be included in an IGCC plant that practices CCS, and this increases the cost of the plant. The higher cost and added energy use of an IGCC plant with CCS results in a much higher cost of CO2 avoided. In contrast, the only difference between CTL plants that vent CO2 and CTL plants that use CCS is the need to dehydrate and compress the concentrated CO2 stream that would otherwise be vented.

Because there are no thermochemical-conversion plants in the United States, this section provides a detailed technical and economic analysis of conceptual plants simulated with Aspen Plus software. Both indirect- and direct-liquefaction models have been developed.

To evaluate the commercial potential of coal conversion to liquid transportation fuels, the panel carried out a series of evaluations of various conversion processes and options. They all used a consistent capital-cost basis and the same set of economic and operational parameters.4 Thus, the relative costs of fuels produced with different processes and among different options for a given process are quite accurate, although substantial uncertainty may be associated with the absolute cost. Details of this approach and the capital-cost basis and the economic and operational parameters used are given elsewhere (Kreutz et al., 2008).

Indirect-liquefaction models include CTL, BTL, CBTL, and combined electric-power and fuel generation (polygeneration). To keep the extent of work

and the number of cases evaluated within reason, a number of parameters were fixed, such as gasifier type, coal type, and location. For example, the analyses were all based on a Texaco–GE entrained-flow gasifier and Illinois no. 6 coal.5 Equipment capital costs were from recent detailed design studies and were updated to 2007 dollars on the basis of the Chemical Engineering Plant Construction Cost Index. Plant design involved material-balance and energy-balance calculations with Aspen Plus. Most of the studies were based on a synthesis-process configuration that involved recycling of unconverted synthesis gas leaving the reactor back to the reactor to achieve maximum synthesis of hydrocarbons. The configuration will be referred to as recycling. The recycling cases included designs both with and without CCS. The designs involved generation of power from fuel-gas streams for use in the plant, and excess power was sold to the grid. Some of the designs involved passage of synthesis gas through the synthesis reactor without recycling of the unconverted fraction and with generation of power from the unconverted gases and are referred to as once-through cases. Those cases typically produced large quantities of power. They also included designs with and without CCS. The costs and performance estimates cited here correspond to those in a workbook that is available at http://cmi.princeton.edu/NRC_AEF_workbook.

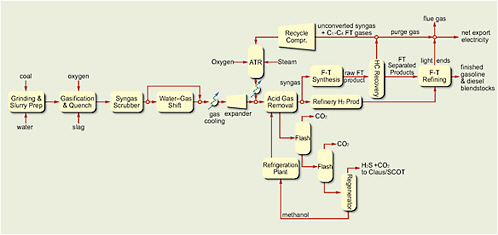

Coal to Liquid Fuels

Table 4.1 summarizes the results of the analysis of conceptual CTL plants operating in the recycle mode with and without CCS (Kreutz et al., 2008; Larson et al., 2008). Each column shows the performance, cost, and greenhouse gas life-cycle emissions for the indicated process configuration. Figure 4.4 shows the plant configuration with the main process units indicated for diesel and gasoline production using FT synthesis. The plant has FT reactor tail-gas recycling and venting of the CO2 recovered from the synthesis gas to the atmosphere. In this configuration, an autothermal reformer is used to convert the light hydrocarbon gases produced during synthesis back into synthesis gas, which is then sent to the FT unit for further conversion into liquid fuels. The paraffinic diesel and the higher-range material made require additional refining to produce high-quality diesel and jet fuel. The naphtha-range material has a low octane number and thus requires substan-

TABLE 4.1 Coal to Liquid Fuels by Fischer-Tropsch and Methanol to Gasoline Conversion Routes With and Without Carbon Capture and Storage

|

|

CTL FT Recycling Without CCS |

CTL FT Recycling With CCS |

CTL MTG Recycling Without CCS |

CTL MTG Recycling With CCS |

|

Inputs: |

|

|

|

|

|

Coal, tons/day (as received) |

26,700 |

26,700 |

22,900 |

23,200 |

|

Outputs: |

|

|

|

|

|

Diesel, bbl/d |

28,700 |

28,700 |

0 |

0 |

|

Gasoline, bbl/d |

21,290 |

21,290 |

50,000 |

50,000 |

|

Total liquid fuels, bbl/d |

50,000 |

50,000 |

50,000 |

50,000 |

|

Efficiency, percent (low heating value) |

49.1 |

47.6 |

54.2 |

52.9 |

|

Electricity, MWe |

427 |

317 |

145 |

111 |

|

CO2 vented at the plant, tonnes/hr |

1,427 |

209 |

1,200 |

230 |

|

CO2 stored, tonnes/hr |

0 |

1,217 |

0 |

970 |

|

Economics and metrics: |

|

|

|

|

|

Total plant cost (TPC), millions of dollars |

4,880 |

4,950 |

3,940 |

4,020 |

|

Specific TPC, $/bbl per day |

97,600 |

98,900 |

78,800 |

80,400 |

|

Total liquid fuels cost,a $/gal gasoline equivalent |

1.50 |

1.64 |

1.47 |

1.57 |

|

Break-even oil price,b $/bbl |

56 |

68 |

47 |

51 |

|

Life-cycle GHG emissions, kg CO2eq/GJ (low heating value) |

205 |

98 |

192 |

109 |

|

FT liquids per petroleum-derived diesel emissions |

2.23 |

1.07 |

2.09 |

1.18 |

|

Cost of avoided CO2, $/tonne |

Not applicable |

11 |

Not applicable |

10 |

|

Fuel cost: |

|

|

|

|

|

With $10/tonne CO2, $/gal gasoline equivalent |

1.71 |

1.74 |

1.69 |

1.69 |

|

With $50/tonne CO2, $/gal gasoline equivalent |

2.58 |

2.12 |

2.52 |

2.18 |

|

With $100/tonne CO2, $/gal gasoline equivalent |

3.67 |

2.60 |

3.66 |

2.79 |

|

Note: Details of models can be found in Kreutz et al. (2008) and Larson et al. (2008). aFor simplicity and consistency, the panel assumed that electricity was sold to the grid at the average 2007 generating price in the United States, which was $60/MW with $0/tonne of CO2 charged. All table entries have that basis. If the value of the electricity is set at $80/MW, the total liquid-fuels cost decreases from $1.50/gal gasoline equivalent to $1.41/gal gasoline equivalent for CTL FT venting and from $1.64/gal gasoline equivalent to $1.58/gal gasoline equivalent for the CO2 storage version. For $50/tonne of CO2, the fuel cost decreases by $0.90 for venting and by $0.36 for CO2 storage. bThe break-even crude-oil price is defined as the price of crude oil in dollars per barrel at which the wholesale prices of petroleum-derived products would equal (on a dollars-per-gigajoule basis) the calculated cost of production of the synthetic fuels. See Kreutz et al. (2008) for a detailed definition. |

||||

FIGURE 4.4 Schematic of plant for production of diesel and gasoline from coal with FT synthesis, recycling of unconverted syngas, and reforming of light hydrocarbons; separated CO2 is vented to the atmosphere.

tial refining to produce high-octane gasoline. The estimates in Table 4.1 include the cost of upgrading to fuel products. Details of the Aspen Plus modeling and other aspects of the analysis are presented by Kreutz et al. (2008).

That commercial-scale conceptual plant produces gasoline and diesel at 50,000 bbl/d from 26,700 tons of as-received bituminous coal per day. That yields a ratio of 1.9 barrels (80 gal) per ton of coal and an overall plant efficiency of 49 percent (on the basis of the lower heating value [LHV]). The plant generates 874 MW of electric power; 447 MW are needed on site, and 427 MW are sold to the grid. In this configuration (Figure 4.4), the CO2 produced during the conversion process, amounting to 1427 tonnes per hour, is vented to the atmosphere. The CTL plant with CCS takes advantage of the higher pressure of the CO2 coming off the acid-gas removal flashes to minimize the compression-power requirements but still consumes more than 100 MW in compression-power consumption, reducing the plant export of power to the grid to 317 MW of electricity.

Figure 4.5 shows the schematic of a coal-to-gasoline plant that uses methanol synthesis followed by MTG. The plant uses the same equipment at the same size from coal storage up to the front of the synthesis loop as the FT plant. Because

FIGURE 4.5 Schematic of plant for production of gasoline from coal with methanol synthesis followed by MTG process with recycling and CCS.

of the higher selectivity of the methanol synthesis and MTG conversion, the remainder of the plant is less complex than the FT plant. The plant vents the CO2 separated from synthesis gas to the atmosphere and uses recycling of unconverted gases around the methanol-synthesis reactor. To be consistent with the FT plants producing only liquid transportation fuels and power, the LPG produced in the MTG process was burned to produce electricity in the power island. The plant produces gasoline at 50,000 bbl/d from 22,900 tons of as-received subbituminous coal per day. The MTG scheme yields 2.2 bbl of gasoline per ton of coal and an LHV plant efficiency of 54 percent. The somewhat higher liquid yields occur because the methanol syntheses and MTG are more selective in their conversion efficiency and gasoline is less dense than diesel fuel. The plant generates an estimated 440 MWe and sells an estimated 145 MWe to the grid. Good engineering data on the MTG portion of the plant are lacking, and the estimates of generated power need to be refined as better data become available. Higher plant efficiency occurs because the MTG plant produces less electricity, which has a lower efficiency of production. The plant vents CO2 at about 1,200 tonnes/hr.

To estimate the total life-cycle greenhouse gas emissions from these processes (from coal mine to wheels), it is necessary to estimate the total emissions resulting from the mining and the transportation of the coal from the mine to the plant,

including methane emissions from mining, emissions associated with fuel distribution from the conversion plant to the end user, emissions due to conversion processes at the plant, and emissions resulting from the combustion of the fuels produced.6 Because the plants produce excess power, a greenhouse gas credit is given for power production on the basis of the greenhouse gas emissions associated with an IGCC plant that generates the same amount of power and has no CCS.

This carbon-accounting method estimates the life-cycle emission for the venting CTL FT case to be 205 kg CO2 eq/GJ (LHV) of produced fuels (about 1 ton of CO2 per barrel of product) and about 192 kg of CO2 eq/GJ (LHV) of produced fuels for the coal-to-methanol-to-MTG case. For production of the fuels from conventional petroleum, the greenhouse gas life-cycle emission is estimated from Argonne National Laboratory’s Greenhouse Gases, Regulated Emissions, and Energy Use in Transportation (GREET) model to be about 92 kg CO2 eq/GJ. Therefore, the life-cycle emission is about 2.2 times that of fuels produced from petroleum.

The capital cost (total plant cost) of the FT plant without CCS (first column in Table 4.1) is estimated to be $4.9 billion. That is equivalent to a capital cost on a daily-barrel basis of $97,600. For the consistent economic parameters used in this report, a coal price of $42/ton ($1.71/GJ), and an electric-power value of $60/MWh, the resulting cost of the fuels would be $1.50/gal gasoline equivalent. In terms of a break-even oil price, that translates to $56/bbl (see Table 4.1 footnote for definition). If electricity is valued at $80/MW rather than $60/MW, the fuel-production cost decreases by $0.09/gal gasoline equivalent to $1.41/gal gasoline equivalent, and the decrease remains $0.09/gal gasoline equivalent for the several CO2 cost entries in the table. The total plant cost of the MTG plant is estimated at $3.9 billion (third column of Table 4.1); on a daily-barrel basis, the capital cost is $78,800 per stream-day barrel (SDB). That is lower than the cost of the FT plant because of the somewhat higher complexity of the FT process and the larger refining requirement to produce fuels that meet the product specifications. The resulting cost of the high-octane gasoline produced is estimated at $1.47/gal, which equates to a break-even oil price of about $47/bbl. The impact of $80/MW

versus $60/MW is a $0.04/gal gasoline equivalent reduction in fuel cost because an MTG plant sells less electricity than an FT plant does. For MTG, if LPG is sold at the current market price, the cost of fuel production decreases by about $0.20/gal gasoline equivalent to $1.26/gal gasoline equivalent. Those costs for the production of liquid transportation fuels from coal are comparable to the costs in a report by the RAND Corporation (Bartis et al., 2008).

The economic results shown above are for cases in which there is no tax on CO2. If CO2 were to be taxed in the future so that a plant operator had to pay to emit CO2 to the atmosphere, the economic situation could change substantially. If the tax imposed on CO2 were $100/tonne, the cost of fuel from this coal-based FT plant would increase from $1.50/gal gasoline equivalent to $3.67/gal gasoline equivalent. The MTG plant would see a similar impact on the cost of the gasoline produced and an increase from $1.47/gal gasoline equivalent to $3.66/gal gasoline equivalent.

The second and fourth columns in Table 4.1 summarize the results for the conceptual FT and methanol-to-MTG plants with recycling and with CCS. In this case for FT, bituminous coal at 26,700 tons/day produces liquid fuels at 50,000 bbl/d. Overall plant efficiency is reduced slightly, from 49 to 48 percent, in this case because of the need to compress and dry the captured CO2 to 2,100 psi for pipelining and geologic storage. About 85 percent of the CO2 produced during the conversion process is captured, and only 209 tonnes/hr are emitted to the atmosphere. Although the fuel output is the same with and without CCS, the net electric-power generation is reduced to power the compressors for the captured CO2. A greater percentage of the CO2 produced in the conversion process could be captured by changing the overall configuration to include, in addition to an autothermal reformer, additional water–gas shift and CO2 capture facilities to produce more H2, which could be used as fuel in the gas turbine in the combined-cycle power island. The same comments apply to the methanol-to-MTG case.

With the same method as in the previous case (except that the electric-power greenhouse gas credit is now based on an IGCC plant with CCS), the greenhouse gas life-cycle emission is estimated to be reduced to 98 kg of CO2 eq/GJ for the FT unit producing liquid fuels. The ratio of the greenhouse gas life-cycle emissions for the FT liquids to that for petroleum-derived diesel is 1.1, which means FT liquids essentially have the same greenhouse gas life-cycle emissions as petroleum-derived fuels. The ratio must be interpreted carefully. The assignment of the greenhouse gas emissions associated with the generation of the excess electric power is somewhat arbitrary and depends on the power-generation technology that is displaced