Merits and Viability of Different Nuclear Fuel Cycles and Technology Options and the Waste Aspects of Advanced Nuclear Reactors (2023)

Chapter: Appendix G: Reprocessing and Geologic Disposal of TRISO Fuel

Appendix G

Reprocessing and Geologic Disposal of TRISO Fuel

TRISO FUEL REPROCESSING

Several advanced reactor designs intend to use TRistructural ISOtropic (TRISO) fuel, which is attractive for its robustness and ability to withstand high temperatures. However, these properties also make processing the fuel to access and recover fissile material a significant challenge, so most research has focused on developing head-end steps. In general, processing of TRISO fuel elements consists of the following steps: “mechanical preparation, removal of carbon external to the SiC shell, removal of the SiC shell, removal of carbon layers between the SiC shell and heavy metal kernel, and dissolution of the heavy metal kernel” (Del Cul et al., 2002). Initial work in TRISO fuel processing involved burning the outer layers of graphite and then crushing the fuel particles using steel rollers to expose the fuel for dissolution in nitric acid, followed by processing using the standard PUREX flow sheet (IAEA, 2008). While effective, this method releases CO2 containing quantities of 14C above regulatory limits, and therefore must be paired with an expensive off-gas treatment system and sequestration methods that generate significant quantities of calcium carbonate waste (Del Cul et al., 2002). Consequently, alternative strategies that simplify processing steps, minimize waste, and can take advantage of existing industrial processes and equipment are the focus of current research (Del Cul et al., 2002).

Methods have been developed to recover fissile material from TRISO fuel in forms suitable for both aqueous and nonaqueous separations. The initial steps are the same in both cases and involve crushing and milling the fuel compacts into fine particle size. The fuel is then dissolved by nitric acid leaching for aqueous processing, or by carbochlorination for nonaqueous processing (Del Cul et al., 2002). An alternative approach under development uses supercritical CO2 containing tributylphosphate to extract uranium from crushed TRISO particles (Zhu et al., 2012). Other nonaqueous options include fluoride and chloride volatility and direct electrochemical dissolution (IAEA, 2008).

Savannah River National Laboratory has developed and patented a molten salt dissolution process in which the outer graphite layer of the TRISO fuel is oxidized by a nitrate salt at temperatures between 400 and 700°C, generating carbon dioxide, carbonate salts, nitrous acid, and nitrogen (Pierce, 2017). Addition of an alkali metal hydroxide, either in the same or a subsequent step, oxidizes the silicon carbide layer, and residual nitrate salt then oxidizes the inner carbon layers that surround the fuel kernel. Finally, a metal peroxide or superoxide is used to solubilize the fuel kernel. Nitric acid is also required for this dissolution step if the fuel contains thorium oxide. The overall process can occur in one step, using a single processing vessel, or by a multistep sequential method. For the former, mechanical pretreatment of the TRISO particles is typically required to expose the inner layers of

the fuel element so that all chemical reactions can occur simultaneously. The multistep method allows the products of graphite layer oxidation to be separated out as low-level waste.

Remaining challenges for TRISO fuel reprocessing include handling the volatile fission products in the off-gas, improving the recovery efficiencies, and scaling up all steps of the process. Nitric acid leaching can leave solid residues, such as undissolved noble metals, SiC shell fragments, SiO2, and NaSiO3-containing residues, which can lead to the formation of silicic acid and complicate subsequent separation steps (Del Cul et al., 2002). Handling and disposing of the large amount of 14C-contaminated graphite presents another challenge, as discussed further in Chapter 5. Developing improved methods for removing the graphite layers surrounding the fuel kernel could enable their disposal as low-level waste rather than high-level waste (Todd, 2020).

TRISO FUEL FORM AND WASTE DISPOSAL

As one of the most well-studied of the advanced fuel forms, TRISO particles serve as a useful example of the type of attention (research and development) required in order to qualify a fuel for disposal. The United States already has TRISO-based fuels that require storage and disposal at the Fort St. Vrain (FSV) reactor site in northeast Colorado, and the challenges in dealing with that spent fuel can provide valuable lessons for future management of advanced fuel forms. A number of studies, in the United States and worldwide, have analyzed requirements for storage of spent TRISO fuel, direct disposal of spent TRISO fuel in a repository, and processing and treatment options for spent TRISO fuel prior to disposal. From these studies, additional research needs for identifying safe methods for disposing of spent TRISO fuel can be identified. More generally, the type and extent of research and testing needed to understand in-reactor behavior and analyze disposal options for TRISO fuel demonstrate the amount of work required to be able to safely manage and dispose of any advanced fuel form. In-reactor testing of new fuels can take several years.

The inventory of spent TRISO fuel in the United States was generated by the operation of a high-temperature, gas-cooled reactor by the Public Service Company of Colorado that ran commercially from 1979 to 1989, generating 23.35 MTHM (metric tons of heavy metal). Over a third of this fuel was transferred to Idaho National Laboratory (INL), but in 1989, the state of Idaho blocked further shipments to INL. Thus, the Public Service Company of Colorado constructed an independent spent fuel storage facility at the reactor site. The balance of the fuel has been transferred to the storage facility. In the mid-1990s, the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) took possession of the fuel storage facility. The fate of the fuel is constrained by legal agreements between DOE and the states of Idaho and Colorado. The 1995 Settlement Agreement prevents the transfer of the fuel from FSV until a permanent geologic repository or interim storage facility is established outside of Idaho (IDEQ, 1995). By 2035, all DOE spent fuel must be removed from Idaho. The agreement also limits the total quantity of spent fuel (16 MTHM) that can be shipped to Idaho. In an agreement between the state of Colorado and DOE, DOE must remove all of the spent fuel from FSV by 2035 or pay a penalty. This history of the stranded TRISO fuel at FSV illustrates the larger challenges of dealing with nuclear fuels stranded at reactor sites (see NWTRB, 2017).

Radiation Effects on TRISO Fuel

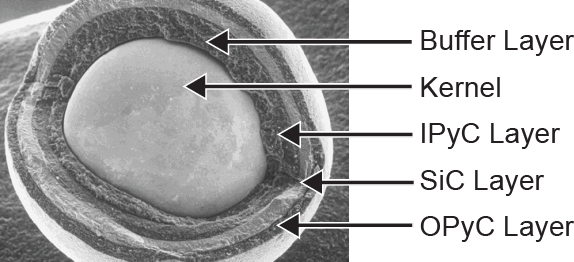

As with any new nuclear fuel type, TRISO particles must undergo in-reactor testing to understand radiation effects on the fuel material. The source term of the fuel material is the starting point of any safety assessment. It is especially important that this source term characterize the redistribution of and phase formation of radionuclide phases as they are generated during reactor operating conditions. In a very complete study, Gerczak et al. (2020) examined 72 cylindrical compacts, each with 4,100 TRISO kernels. Irradiation of the compacts for ~620 full-power days to burnups of 11 to nearly 20 percent fissions per initial heavy metal content showed no indication of TRISO-layer failure during the in-pile irradiation. Concerning radionuclide distributions, the authors noted “high-Z features” that accumulated at the I[inner]PyC/SiC interface, which was interpreted as the interaction of fission products and actinides with the TRISO layers. There was also evidence of increased susceptibility of the SiC layer to decomposition at the SiC/O[outer]PyC interface. Another detailed study (van Rooyen et al., 2018) made atomic-scale observations of SiC as a function of dose using transmission electron microscopy of irradiated TRISO

fuel particles. Principal observations included (1) “black” spots, probably a mix of smaller dislocation loops; (2) polygonal voids; and (3) Frank loops, which act as nucleation sites for intergranular alpha-SiC and Pd-silicide precipitates. Van Rooyen et al. (2018) also found that the void distribution is not uniform and bimodal, and a high concentration of smaller voids occur at stacking faults. Furthermore, the retention of radionuclides appeared to be inversely proportional to void size.

Direct Disposal of TRISO in a Geologic Repository

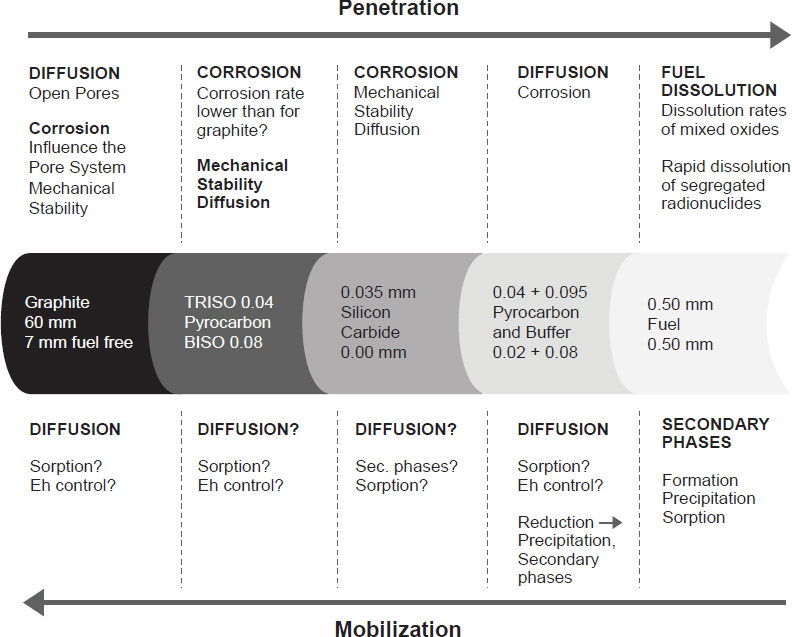

There have been many studies relevant to the direct disposal of very-high-temperature TRISO fuels in a geologic repository, with most analyses examining the properties and performance of the graphite matrix and SiC coating within a geologic disposal environment. In general, because of their multibarriers within the waste form and matrix (as depicted in Figures G.1 and G.2), high-temperature reactor (HTR) fuel elements are considered “well designed” for direct disposal in a geologic repository (Fachinger et al., 2006).

Studies investigating properties of the graphite matrix have shown that it limits the amount of water that may come into contact with the fuel kernels (Fachinger et al., 2006). Because the embedding matrix will strongly delay groundwater contact with the fuel particles, radiolysis is probably not an important factor in the determination of fuel dissolution rates (Grambow et al., 2010). “Radionuclide transport in the water-filled graphite matrix porosity is controlled mainly by diffusion with calculated breakthrough times over a distance of 1 cm ranging from a few days up to a year” (Fachinger et al., 2006). The corrosion of matrix graphite has been investigated in water, as well as in concentrated magnesium and sodium solutions, and significant graphite corrosion was observed only

SOURCES: Adapted from Fachinger et al. (2006); Grambow et al. (2010).

SOURCE: Idaho National Laboratory.

in the salt brines (Grambow et al., 2008). The dissolution rate in the salt brines showed a linear relation to dose, and at the highest dose (3.5 MGy), the rate was 1 mm/million years.

The properties and performance of SiC or other carbides are central to the overall performance of TRISO spent fuel in a geologic repository. Assuming that nonuniform corrosion does not occur, lifetimes of the pyrocarbon and SiC layers are estimated at 103–105 years depending on corrosion conditions, irradiation doses, and temperature; however, this requires confirmation by experimental studies (Fachinger et al., 2006). The coatings are thought to make spent TRISO fuel more resistant than conventional high-level waste forms to rapid, initial radionuclide release, based on the assumptions of the diffusion of water into the pebble in a few years, the failure of the SiC coating in 10,000 years, and the dissolution of kernels in approximately 106 years under reducing and 104 years under oxidizing conditions (Grambow et al., 2008, 2010). Studies of radiation effects (Katoh et al., 2012) and on the diffusion of fission product elements through the SiC layer (Malherbe, 2013) have provided a fundamental basis for understanding the performance of SiC. In a model that treats the SiC layer as analogous to a pressure vessel that retains gases produced by fission and radioactive decay, Peterson and Dunzik-Gougar (2011) “demonstrated that corrosion rates, temperature evolution over time and the thickness of the OPyC and SiC layers have a significant effect on the estimated time to particle failure. The dimensions of the kernel, buffer and IPyC layers along with the strength of the SiC layers and the pressure in the TRISO particle did not significantly alter the time to particle failure.” The mechanical properties of TRISO fuel are also an essential aspect of their performance, and new techniques such as X-ray tomography can be used to develop an advanced understanding of these properties, particularly as a function of radiation type and dose (Liu et al., 2020).

Additional studies have examined the potential for radionuclide release from TRISO particles. Leaching tests using granite water, clay-pore water, and a Q-brine have been performed on irradiated spherical fuel elements to simulate repository conditions. These experiments showed two different phenomena with the respect to the retention of 137Cs and 154Eu: (1) intact fuel kernel particles retain fission products nearly completely, and (2) releases from defective or failed particles and from the matrix sphere are rapid, but the contribution to released radioactivity is small. Given the long lifetimes of SiC layers noted above, the coating should be sufficient to retain the major inventory of fission product elements that will decay to near-zero values within the first 1,000 years (Nabielek et al., 2009). Additionally, very high temperatures (1,800°C) over extended periods (650 hours) have confirmed that SiC maintained its functionality as a fission product barrier (Gerczak et al., 2020). A deterministic performance assessment for deep-burn modular high-temperature reactors for disposal in the proposed repository at Yucca Mountain suggested that the lifetime of the graphite matrix exceeds that of the TRISO particles (van den Akker and Ahn, 2013). This result depends very much on the redox conditions, and TRISO kernels have a low durability in the highly oxidizing conditions of the Yucca Mountain repository. The analysis does not explicitly capture the variations in chemical behavior as a function of chemical conditions (e.g., congruent release of radionuclides with graphite matrix corrosion); however, despite these uncertainties, the results indicate that the release of radioactivity complies with federal dose standards.

Processing and Treatment of TRISO Fuel Elements

As mentioned in Section 5.4.2 and Box 5.3 in Chapter 5, graphite-moderated reactors will generate considerable volumes of radioactive graphite, and as a result, the direct disposal of used prismatic fuel blocks (or graphite pebbles of pebble-bed modular reactors [PBMRs]) is not considered viable (Grambow et al., 2006). Techniques such as low-temperature (H2SO4 + H2O2) and high-temperature (H2SO4 + HNO3) acid treatments can be used to separate kernel fuel coated particles from the graphite matrix with high efficiency and nearly complete separation (Guittonneau et al., 2010). Processing TRISO fuel assemblies and pebbles may allow for the embedding of TRISO fuel kernels into waste form matrices (e.g., nuclear waste glass, SiC), which would substantially reduce the volume of disposed waste (Grambow et al., 2006). The vitrification of fuel kernels can be accomplished by glass melting (1200–1300°C) or sintering (700°C). The lower temperature of sintering has the attractive potential of conserving as much as possible the strong confinement properties of the fuel kernels. These lower-temperature processing techniques are under investigation but have already shown promising results. Embedding the kernels in SiC using standard techniques of liquid sintering or hot pressing (1800–2000°C), on the other hand, may damage fuel particles and cause the release of fission products.

Future Research Needs for TRISO Fuel

Despite the significant research efforts on TRISO fuel properties described above, additional research is required to better understand the behavior of TRISO fuel under irradiation and in a repository environment, as well as to improve methods for processing spent TRISO fuel and managing radioactive graphite wastes.

The coatings on the kernel particles experience radiation damage from in-reactor neutron irradiation, fission fragments, and alpha decay events (i.e., alpha particle and recoil nucleus), and the different radiation effects must be understood over the appropriate timescales and temperature regimes (Fachinger et al., 2006). In-reactor formation and diffusion of fission product elements and uranium has been shown to lead to their accumulation at the interfaces of the layers and to some degradation of the layers (Gerczak et al., 2020). Developing a broader understanding of the behavior of radionuclides in TRISO fuels during reactor operation and over the long periods required for their isolation in a geologic repository would be valuable, in particular understanding the effect of irradiation as a function of temperature and radionuclide formation, diffusion, and release through the SiC layer (Gerczak et al., 2020). An additional aspect to understand is “the influence of the internal pressure within the coated particles on the lifetime of the coating and new phase formation between the fuel and the coating layers” (Fachinger et al., 2006). SiC has been selected as a coating-material because of its neutron radiation damage tolerance at high doses, strength, and chemical inertness, but radiation damage can lead to changes in microstructure that affect the integrity and barrier function of SiC (van Rooyer et al., 2018). The presence of defects will affect fission product transport through the SiC layer, so experimental data (e.g., by ion beam or in-reactor irradiations) on the formation, types, and migration of radiation-induced defects is needed (van Rooyer et al., 2018). Additionally, the dissolution behavior of fuel kernels, “especially with respect to the influence of irradiation and incorporation of fission products,” and the potential for “rapid release from segregated, radionuclide phases” must be understood (Fachinger et al., 2006).

For disposal of spent TRISO fuel, the safety assessment will require integrated models that describe the release of radionuclides over periods relevant to a safety analysis of a geologic repository. The performance of TRISO fuels must be investigated as a function of external parameters: type and dose of radiation; type of aqueous phase–solid interactions as a function of solution composition and temperature (Fachinger et al., 2006). Because the graphite matrix provides a barrier to the contact of groundwater with the TRISO fuel kernels, it is important to investigate the mechanisms by which water may penetrate the graphite matrix and understand the effect of aqueous phases on the microstructure of the graphite matrix (Fachinger et al., 2006). The release of radionuclides may, in some cases, be limited by radionuclide solubility constraints. Understanding the role of solubility limits on radionuclide mass transfer in the graphite pore fluids should be investigated within the constraints of hydrodynamic movement of fluids and the pore fluid chemistry, and considering that these phenomena will be affected by the radiolysis of water and the corrosion of graphite (Fachinger et al., 2006). For TRISO fuel kernels embedded in a nuclear waste form matrix (e.g., borosilicate glass, SiC, or ZrO2), outstanding questions include the following: (1) Are sintered matrices

(glass and ZrO2) sufficiently dense to prevent water diffusion toward the fuel particles without the dissolution of the matrix? (2) Once the embedding matrix has altered to secondary phases, which will require hundreds of thousands of years, will the matrix still protect the fuel particles? (3) What are experimentally determined values of the diffusive mass transfer of radionuclides across a corroded embedding matrix? (Grambow et al., 2008)

Detailed investigations of the corrosion mechanisms of irradiated pyrocarbon and SiC layers are also still required (Fukuda et al., 1982; Grambow et al., 2010). There have been proposals for the importance of the graphite matrix in reducing the release of radionuclides from TRISO fuels; however, before one can claim credit for this barrier function, there is a need for detailed materials studies of the mechanisms of graphite corrosion in repository environments (van den Akker and Ahn, 2013). Similarly, although degradation measurements of carbonaceous materials relevant to TRISO fuel behavior in a geologic repository are available, the data are sparse. Confirmatory experiments need to be completed over the appropriate temperature and pH ranges for the appropriate solution compositions that are expected in different geologic settings (Morris and Bauer, 2005). “A better understanding of the corrosion rates of the O[outer]PyC and SiC layers, along with increasing the quality control of the OPyC and SiC layer thicknesses, can significantly reduce the uncertainty in estimated time to failure of spent TRISO fuel in a repository environment” (Peterson and Dunzik-Gougar, 2011). For long-term, safe disposal of kernels from TRISO fuel, it is important to investigate (1) the effect of radioactive alpha decay of actinides on the structural integrity of the various coatings, including the atomic scale radiation damage effects and volume expansion; (2) He accumulation in the particle kernels that may lead to pressurization and increase the probability of particle coating failure; (3) the effects of lithostatic pressure; and (4) material fatigue mechanisms (Nabielek et al., 2009). It may be possible to improve on the present TRISO particle design, for instance by including a thin layer of ZrC among the coatings to obtain better performance at higher temperatures (Malherbe, 2013).

The management of irradiated graphite waste represents a considerable research and development challenge regarding retrieval, characterization, treatment, reuse, and final disposal. The activation of impurities, which vary considerably depending on the grade of the graphite, during neutron irradiation of the graphite determines the degree of radionuclide contamination. However, the European Commission CARBOWASTE project has demonstrated that a number of the radionuclides (e.g., 3H, 36Cl, 60Co, and 63Ni, as well as 14C) can be removed with high efficiency (von Lensa et al., 2011). Previous research on TRISO processing has demonstrated that kernels can be separated from the graphite matrix (Guittonneau et al., 2010), but this work must be expanded to study the effects of neutron irradiation on the compacts used within the reactor and to understand the fate of volatile elements, such as 36Cl and 14C, during the processing treatment.