2020 Census Data Products: Demographic and Housing Characteristics File: Proceedings of a Workshop (2023)

Chapter: 9 Observations on Use Cases and Needs

9

Observations on Use Cases and Needs

The penultimate sessions of the workshop were devoted to feedback for the Census Bureau about areas that were not captured in the form of use cases comparing the March 2020 Demographic and Housing Characteristics (DHC) demonstration data to the Summary File 1 (SF1) published data. This chapter discusses strategies for using the 2020 decennial data and beyond and reconsideration for the Census Bureau on how to obtain and evaluate feedback on its data products.

STRATEGIES FOR USING THE 2020 DECENNIAL DATA AND BEYOND

George Carter (U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development [HUD]) moderated a panel that offered reflections on using the 2020 decennial data and their impact on other products, such as the American Community Survey (ACS) and the 2030 Census. All speakers who were government officials noted that their views were their own and not their agencies’. Carter offered five guiding questions for all panelists (see Box 9-1).

Housing

Carter stated that HUD sponsors housing surveys collected under interagency agreements with the Census Bureau:

- American Housing Survey;

- Survey of Construction;

- Survey of Market Absorption of New Multifamily Apartments;

- Manufactured Housing Survey; and

- Rental Housing Finance Survey.

The largest of these is the American Housing Survey. It is a longitudinal survey of housing units sampled from the Master Address File. He noted that except for the sampling frame coming from the Master Address File and geographic definitions coming from the decennial census, HUD surveys are not directly affected by the decennial data. Carter explained that the program parameters HUD calculates (e.g., fair market rents, income limits) are drawn from the ACS because it contains more detailed data on housing than the decennial and is collected more frequently.

Carter explained that HUD does create some data products that incorporate decennial data, including the Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing Tool and other applications of Geographic Information Systems (GIS). Census data–informed geographies are also used to tabulate data and are included in analyses of racial and ethnic disparities in home ownership. Other housing topics that are informed by decennial data are research on residential segregation, data on persons and families experiencing homelessness in past censuses, populations living in group quarters, and housing vacancy. Relevant links to learn more about HUD’s surveys and research that rely on decennial data are provided in Box 9-2.

Schools

Doug Geverdt (National Center for Education Statistics [NCES]) described his experience working for the Census Bureau prior to NCES, which sponsors the School Neighborhood Poverty Estimates, the Education Demographic and Geographic Estimates program, and the school district boundary update program.

Geverdt stated that his primary concern with the current DHC data is that it cuts 77 percent of the school district data that were available in 2010, which presents a problem for education users. However, he asserted that this was an even larger problem for the Census Bureau than for NCES, given the Census Bureau’s prior messaging. “Remember that the 2020 advertising campaign promised that the census would provide data to schools,” Geverdt said. He suggested it will be helpful for schools to know they will lose greater than 75 percent of their data. Although most of NCES’s work involves the ACS, he cautioned that substantial, unexpected

cuts to 2020 school district data will be a problem in 2030 when encouraging census responses to help schools.

Geverdt offered an example and provided a graphic in his presentation, displaying 1,400 census tracts that intersect the Los Angeles Unified School District. While this district of 4.6 million people will get Detailed DHC (DDHC) tables, the district itself will not be able to use them because school districts are not designated as a DDHC publication geography. He asked how the privacy-loss budget can be explained to school districts when even large ones such as Los Angeles Unified are excluded.

Geverdt commented that the DHC impact seems to focus more on content elimination than noise infusion, and the story seems less to do with privacy versus accuracy and more to do with privacy versus access. He equated this to information rationing and cautioned that noise infusion needs to be explained not only in general, but also in the context of data budgets and the privacy-loss budget.

Despite these shortcomings, Geverdt congratulated the Census Bureau for all the outreach it has done. He suggested the Census Bureau look at the relative priorities of what it is advertising, and then use that as its “relative yardstick” to set priorities. “If it is a priority in your campaign, then make it a priority in the products as well.” He advocated for the Census Bureau to publicly commit to not imposing differential privacy on the ACS until after 2030, and stated, “I would take the ACS off the table.” Geverdt cautioned to keep the ACS predictable and suggested that the controversy caused by imposing differential privacy on the ACS will make 2020 look like a “walk in the park.”

Civil and Human Rights

Meeta Anand (Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights) described herself as not a data user per se but as “data adjacent” who works with a lot of advocacy and civil rights organizations that use data in service of their programs. She explained that the Leadership Conference has worked on the decennial census to ensure historically undercounted communities get counted and that the most vulnerable populations get their “fair share of representation and resources.”

Expanding into data equity, Anand implored the Census Bureau to rethink its approach so that it is not looking at data solely in terms of extraction but that the data are in service to communities. She explained that communities need these data to identify equity gaps and seek policy remedies. Anand discussed examples of how DHC data are used for policy advocacy in the areas of voting and fair political redistricting, gentrification, transit equity, and climate justice. ACS and SF1 data are needed to identify and fix practices causing environmental injustice. She pressed for work to be done

at a local level to understand why “their data is not there.” She noted that this is a very hard conversation to have and that it is difficult to explain why one is not able to access the data that they feel are going to allow them to pinpoint the level of harm that they are facing.

Anand stated communities need to be able to understand why it is that they are not able to access what they feel they need to make the correct community decisions and policy. She recognized the trade-off for small groups and more noise infusion, but raised intersectionality as representing different vulnerabilities and emphasized the importance of communicating why one is unable to access data. She wondered whether these stakeholders could be pointed to other groups who can perform analyses for them and draw conclusions.

Anand explained that terminology is confusing because people do not think of themselves as data users. She suggested asking communities what information they are lacking to solve problems rather than asking what data they need for use cases. Anand suggested stepping back in order to articulate the guiding principles for achieving this balance between privacy and access. She urged finding common ground when deciding how much privacy-loss budget to allocate by opening the process earlier to allow input. Anand also suggested providing an alternative if one cannot access unfiltered data. She explained that putting up a screen saying, “You can’t have the data,” without offering a solution leaves people feeling disengaged and not wanting to participate in an ongoing basis.

Tribal Data

Kirk Greenway (Indian Health Service [IHS]) described working with the decennial data to try to figure out where to put water stations for people on reservations during the pandemic. When relying on medical record data in the IHS, there were sometimes 1,500 people who share the same post office box address, so the decennial data were instrumental. Greenway explained that there is additional complexity with decennial data for the Alaska Native population in that some people are highly mobile; to illustrate, he provided figures showing the movement of the population that follows the caribou seasonally.

Greenway stated that those who analyze such data in the IHS realize the data are fundamentally flawed. He argued for the data to be released in a format that is not privacy protected in a Research Data Center, which could be made be available virtually now. He cautioned that people appearing to vanish or never to have existed is going to be a problem and will need an explanation for his user community. Greenway also echoed Geverdt’s observation around communication, “Why isn’t my privacy-loss budget bigger?” Some type of access is going to have to be granted.

Tribes are sovereign nations so they should always be consulted. Greenway explained there are 574 recognized tribes in the lower 48 states, and more American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) groups are represented among the U.S. islands, such as Puerto Rico, Guam, the U.S. Virgin Islands, Marianas, and American Samoa. All of the AIAN populations count. In Greenway’s opinion, “Consensus is what matters in Indian Country; if you do not think you are building consensus, go back to your tribal consultation people and renew or rebuild the strategies that you are using.” Among such groups as the National Council of American Indians, leaders advocate for resolutions against participation in the census in various ways for what they saw were very good reasons.

Greenway explained that there should be greater participation from voices not normally heard such as urban Indians and tribes. He explained that individual identification with a tribe might be identifying because some have under 10 people, and the smallest tribal land is smaller than 3 acres. There is an issue with collecting tribal enrollment lists through directories, and many tribes will view this with suspicion. He concluded by saying the Census Bureau should be optimistic and encouraged the Census Bureau to keep its ongoing outreach, as he thinks it will work.

RECONSIDERATION OF HOW TO OBTAIN FEEDBACK

Amy O’Hara (Georgetown University) offered observations on use cases and needs, and she reminded workshop attendees in her presentation on day two that they were there to try to gather use cases to figure out whether the current parameter settings are harming any of the users. She asserted, “Just because you have not heard from people does not necessarily mean that they are happy with the DHC demonstration data. There could be people who did not know now was the time to engage or what was at stake.”

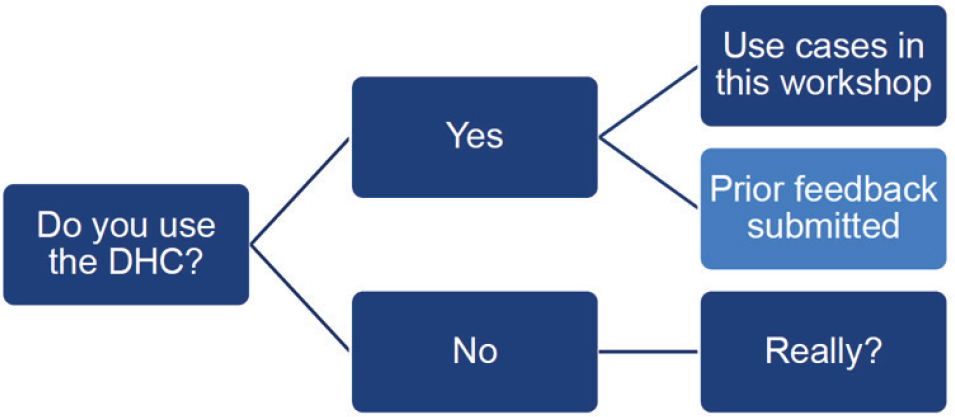

O’Hara noted that framing and phrasing of the discussion was important in soliciting feedback. As Figure 9-1 illustrates, the question should have been, “Do you use the DHC?,” even though a lot of people do not realize they use DHC data. Another question could be, “How did you use the Summary File data?” In addition to the use cases, O’Hara discussed some of the prior feedback that goes back as far as the Federal Register notice issued in 2018 (“Soliciting Feedback from Users on the 2020 Census Data Products,” Document Number 2018-15458).

Some of the use cases in the workshop have crossover to the ACS, Population Estimates, or just to the Public Law 94-171 data. She further implored that when people respond, “No,” they do not use the data, the response should be, “Really?” and to question whether the user is aware of what data they are using.

SOURCE: Amy O’Hara workshop presentation, June 22, 2022.

O’Hara focused part of her discussion on narratives obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request. She displayed snapshots of some of these requests, all of which are available through the Massive Data Institute.1 O’Hara characterized the feedback as sometimes simply, “I use the census data. It’s really important. Please don’t take it away from me.” O’Hara encouraged attendees to peruse the examples to see what people request and why the data are crucially important to them.

She described three submissions that attached detailed information with tangible examples that she paraphrased as, “This is what happens if I’m forced to use the block group instead of block, and this is the degradation of the information that I would have in order to administer my program and deliver services.” These three submitters were never contacted by the Census Bureau. This sentiment was echoed from one verbatim as, “The Census Bureau just keeps asking us for more feedback, and I’m burned out. I’m not even sure they’re listening to what I’ve already said. I don’t have time to continually gin up new examples and send it in.” O’Hara questioned whether that feedback was being cataloged and could be more transparent.

O’Hara discussed what the Census Bureau should be doing differently. She offered that it would be helpful for the Census Bureau to explain whether and how the feedback already received has been acted upon—either in figuring out which data elements will be in which data products, be it the DHC or the DDHC, or which elements are going to be additional

___________________

1 https://mdi.georgetown.edu/resources-and-training/census-resources/

tables. It would also be helpful to communicate when data products will be released based on the feedback and the needs users have already expressed.

She explained there is a big gap in awareness for users when asking, “Do you use the DHC?” to try to figure out whether there are any crisp use cases that could be introduced to this workshop or to make sure that they got their feedback to the Census Bureau before its window closed. Referencing the prior session, “Strategies for 2020 Decennial Data and Beyond,” Amy O’Hara observed that Mary Craigle and Meeta Anand both indicated that people may not even be aware of what they are using. Examples were offered with exact legislation citations that certain jurisdictions require that decennial census data be used for setting salaries, distributing funds, and more. She speculated, “I would guess a lot of people do not know this.” Additional examples of legislative mandates for decennial data are discussed in Chapter 10, which is devoted to resource allocation.

O’Hara stated that some users are required by law to create custom geographies for the population and the number of units within them. Additionally, blocks have always been noisy, but some people are still required to use them because of legal requirements and off-spine geographies that result in custom geographies. There are also legacy reasons, such as systems and models that use blocks and granular information that is needed for estimation and projection methods, and users are accustomed now to receiving data at this level of geography.

Echoing issues raised in the “Decennial Data and Beyond” session, O’Hara underscored a suggestion raised by Doug Geverdt to give users advance notice and be up front with users if the data will not be released. In that same session, Meeta Anand asserted that there are a lot of knowledgeable users that just do not know they need DHC data; O’Hara cautioned that those who have not been part of the discussions will look at the data and “scratch their heads, wondering why the data look a little different than last time.”

Options for Improving User Feedback

First, O’Hara offered that the Census Bureau could improve the engagement process by having more targeted feedback. Second, she suggested that the Census Bureau communicate with banners on 2020 Census product pages that say, “Use blocks with caution,” or simply, “Do not use blocks.” Third, ensure that partners are part of the feedback process on decennial products, as well as the ACS, Population Estimates, or the 2030 Census. Fourth, implore the Census Bureau to be more transparent about the feedback already received by creating indexes, directories, or an online portal where users could “up vote” so that the requests are not repetitive. It would be incredibly useful to provide tools, code, and data viewers to help users

evaluate the data. O’Hara heard from some users that it took hours to pull down the data. She observed that the Census Bureau has made enormous strides in data visualization and other improvements on some of the communication and usability of the products, so O’Hara urged, “Do it here and fix it for next time so that the users are not just left to be the Census Bureau’s QC.” She asked how we can get better data out the door to ensure that this is the trusted resource that it has always been.

Discussion

Garner, serving as the discussant for O’Hara’s presentation, observed that many use cases were discussed during the workshop, but likely many use cases were excluded. She also noted that not all counties are the same and questioned whether higher priority could be given to smaller counties so that they look a little better than they do now.

Garner also stated that the discussions illustrated the importance of communication, including the education of users, many of whom do not realize all of the separate programs that exist or the large size of the Census Bureau. She compared this communication with the heavy training that was required for data users in the year after the ACS was released. They may not be sure which specific census product they are using, but, Garner pressed, “They do have name recognition as the census.” Garner recalled her early training in data analytics when she would use a citation of “Census Bureau” and a professor would explain the need to specify the exact table where the data were found; at the time she did not register why this was important to an early career data user.

Garner then compared the census to a national resource. She posited, “As we look forward, remember that the census data—whether it’s the PL [Public Law 94-171], DHC, DDHC, PopEst [sic], ACS, and any of the numbered surveys—that it is a national resource and just like many national resources, it should be preserved and cared for. . . . Remember that it is a public good paid for by everyone.” Garner emphasized that, especially in this day and age in which accurate and trustworthy data and information for decision-making are more important than ever to democracy, it is important to remember that the census has name recognition for accurate and trustworthy information. She continued by expressing her concern about other data producers—who could be creating data, filling voids, and identifying gaps—and posed the following questions:

- Do we lose that name recognition?

- Do we lose that source?

- Do we lose that credibility?

O’Hara responded with the distinction between equality and equity. She explained, “A lot of the approach to privacy protection for the decennial products seems to have focused on equality. We have to do the same thing to every single cell in the histogram that we are going to put out unless there is an explicit reason to do otherwise. And it is not clear, as we have heard from a couple of days’ use cases, whether that is having equitable results.” She noted that the Decennial Program in particular has a history of allowing the lack of equality, which has led to unique products, such as a different type of enumeration areas and local update of census addresses for remote Alaska.

O’Hara agreed with Garner’s comparison to a national resource and compared it to oil. She offered, “When people talk about data, it worries me because it is a depletable resource, where you have to watch the budget.” Echoing Geverdt’s statement, O’Hara said, “As the data age, isn’t that going to be privacy protection?” She continued that it is important to have a more rational conversation about privacy budget setting and who is at the table when that is happening. She then asked about the half-life of some of these statistics.