Procuring Interoperability: Achieving High-Quality, Connected, and Person-Centered Care (2018)

Chapter: Technical Supplement - Section 4: Lessons From Other Industries

Technical Supplement—Section 4

LESSONS FROM OTHER INDUSTRIES

CASE STUDY 1

SUBMARINE FORCE’S OPEN BUSINESS MODEL APPROACH

Challenges of a closed business model

By the mid-1990s, it had become apparent to the US Navy’s submarine community that their “acoustic superiority”—the undersea margin of technological superiority—had significantly diminished in light of advances in Russian and Chinese submarine technology. The majority of the submarine fleet lost the ability to maintain tactical control over their adversaries, including the ability to detect and localize the adversary through underwater sound. Although an upgrade was necessary, the acquisition mechanisms at the time were too slow in delivery and too expensive to execute. With a recent end to the Cold War, funding for submarine sonar improvements was cut by more than half. How would the United States regain acoustic superiority quickly on only a fraction of the funding previously available?

The traditional change approach involved contracting with the original equipment manufacturer, (i.e., the “prime contractor”), to design, develop, and field changes to the legacy system. A system update via this traditional approach had already been underway, estimated to take 6 years to complete. Under this approach, the unique military requirements would have dictated one-of-a-kind solutions for a set of compatible hardware and software. Before this time, the system design, development, and fielding had been entirely under the purview of a prime contractor. The “prime” hired and controlled third-party subcontractors as needed.

Aligning leadership to change the status quo

Instead, the submarine community embarked on a revolutionary approach to acquiring and improving their primary tactical control tool: sonar. The objectives

were to (1) improve performance faster, (2) deliver additional improvements seamlessly when required, (3) make improvements available to all classes of submarines, and (4) implement an open system based on commercial-off-theshelf (COTS) technology.

Under the new approach (known as acoustic rapid commercial-off-the-shelf insertion, or A-RCI), the navy modified the prime contract that previously included subcontracting third parties. Instead, the third parties became under direct contract to the navy. The prime contractor’s new role became that of an integrator working in a collaborative arrangement with independent hardware and software vendors. The contracts for both the prime and the third parties stipulated that the recognition of success at system certification be either for all parties or not at all. Improved sonar performance capabilities were delivered in a phased approach in one-year increments. Each phase provided significant tactical improvement.

The acquisition strategy involved (1) maximizing the use of products that were not exclusively for governmental use, (2) institutionalizing software reuse, (3) pooling disparate upgrades to the existing legacy system into a single COTS-based development program, and (4) sharing talents and resources among program offices. In short, leverage, leverage, leverage.

Demonstrating initial benefits and garnering support

Because of this revised open environment approach, the U.S. Navy prevented any single vendor from dominating the submarine sonar system development process. By opening up opportunities for other qualified vendors, the new approach reduced barriers to using commercial equipment.

To illustrate this point, phase 1 of A-RCI involved the implementation of a new commercial off-the-shelf signal processor designed to interoperate with the legacy sonar system. The software for this new processor was designed by a small business under a Small Business Innovative Research grant. It was developed and delivered to the submarine fleet in 18 months, and it showed new capability and better performance than what was expected under the legacy approach for 6 years. Moreover, it was inexpensive, given its capacity. With the success of Phase 1, the submarine fleet sponsors and Congress supported the decision to proceed with the remaining phases.

Realizing the benefits of the modular contracting model over time

By that time, this new approach allowed new methods and techniques to be implemented and tested on a 12- to 18-month cycle. An active peer review process, known as advanced processor build (APB), was created to allow rapid building

and testing of sonar software prototypes for the A-RCI’s computing platform. Rather than competing, scientists now collaborated in rapidly implementing techniques that would have taken years to mature in a traditional environment. For instance, the submarine sonar operators’ success rates doubled with the incorporation of the first APB and quadrupled with the second.

The keys to APB success are (1) sharing information across organizations to create the full story, (2) data-driven testing (build-test-build), (3) peer review of new developments, (4) verification of technology before implementation, (5) continuing assessments and measurements, and (6) significant end-user (e.g., fleet user) involvement. Understandably, the submarine fleet end user was the strongest advocate for this new approach.

At its 8-year anniversary, A-RCI had been installed on more than 50 submarines with at least four generations of hardware and software upgrades. According to an internal study, compared with the observed costs over the 10-year previous legacy period, the cumulated 10-year post-A-RCI introduction represented a cost reduction of one-sixth for development and one-eighth for operation and support.

Lessons learned

Although health care’s missions and goals may diverge from those of the U.S. Navy, the extent to which a lack of interoperability hinders the timeliness and efficiency of technology investment draws many parallels. There are several lessons learned from the success of A-RCI:

- Own the architecture and the data, not necessarily the components, while mandating the use of common, nonproprietary interfaces.

- Focus on not only the technical but also the business environments.

- Involve the end user in the design process.

- Do not “eat the elephant in one bite”. Follow an incremental approach with measurable improvements at each stage.

- Recognize and plan to counter the inertia of the incumbency that will resist changes potentially affecting their business model.

- Make sure leaders are held accountable and being rewarded for success.

- Ensure transparency, as it is crucial to maintaining the integrity of the process.

- Make decisions based on data-driven analyses of alternatives, rather than politics or business relationships.

- Develop road maps that provide comprehensive information on capabilities, resources, time frames, and options. Keep them current and make them available to the entire community.

CASE STUDY 2

ADVANCE EXPLOSIVE ORDNANCE DISPOSAL ROBOTIC SYSTEM (AEODRS)

Challenges of a closed business model

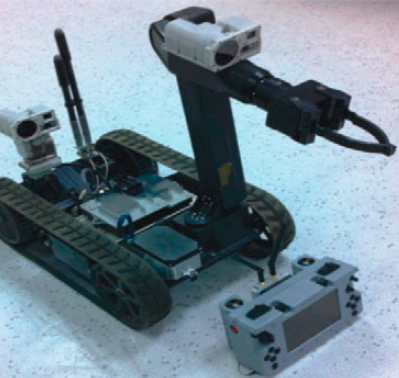

Unmanned ground vehicle (UGV) systems have replaced the need for humans in various tasks. These robots have shown significant benefit to disaster relief, first responders, the military, and law enforcement by conducting tasks that are infeasible, dangerous, or even life-threatening to humans (Hinton et al. 2011; Hinton et al. 2013).

Historically, the UGV industry primarily produced and sold these robots as single systems, designed and built in accordance with proprietary architecture and communication. The different physical and electrical interfaces among robots resulted in difficulties with integrating system components and advancing new capabilities, as well as maintenance and repair. At the time, the vendors were responding to an industry incentive structure that rewarded differentiation. Proprietary platforms, data, and physical interfaces gave one vendor a competitive advantage over another, hence making systems across vendors even less interoperable.

SOURCE: Hinton et al. 2013

Aligning authority to change the status quo

The U.S. Navy’s Advanced Explosive Ordnance Disposal Robotic System (AEODRS) program was established to change the U.S. Navy’s existing paradigm of reliance on closed and proprietary technical solutions. The program introduced an open and modular approach for acquiring these systems (Hinton et al. 2011).

Acting as the primary consumer, the U.S. Navy attempted to engage vendors to develop the modular architecture and define the necessary set of requirements, performance specifications, and interface control documents (ICDs). Despite its laudable goal, there was significant skepticism from within the Department of Defense and significant pushback from the vendor community.

Designing a prototype to establish specifications and support

To break through this challenge, the U.S. Navy developed a prototype (hardware and software) solution to define the system’s architecture, interfaces, and specifications. This AEODRS prototype served to prove to stakeholders and the industry that the promise of open and interoperable modular robotic systems was tangible. The development of the prototype forced the tough trade-offs in setting the standards of the future: too much specificity would stifle future innovation, but loose specifications would render themselves useless if interpretations varied widely. The AEODRS program took what were once single systems and divided them into subsystems with specific capability modules (Kozlowski et al. 2010; Hinton et al. 2013). These modules set the foundation for architecture and interfaces to enable plug-and-play interoperability.

The AEODRS prototype specified clear and concise system requirements, documented performance specifications for each module, and created interface control documents based on existing industry standards. The prototype provided the DoD with the performance specification and ICDs required to procure an individual item. In this case, the U.S. Navy (purchaser) served as the central authority, controlling the architecture, interfaces, and specifications (Hinton et al. 2017).

Realizing the benefits of an open business model

In the past, vendors competed by keeping their systems closed, meaning that only the vendor knew the underlying data and the way data were exchanged. As the industry shifted toward openness, well-defined interfaces became standard in accordance with specifications endorsed by a central authority (in this case the DoD). At the beginning, some perceived this open data structure as a threat to intellectual property. As the industry evolved, however, vendors were provided

a platform for true innovation. The competition between vendors shifted from competing on proprietary data and interfaces to competing on performance capabilities.

The AEODRS prototype and the subsequent adoption of the AEODRS Common Architecture enabled the UGV industry to solve various operational challenges, reduce the time and cost to integrate, and facilitate a shift in the industry toward innovation. The well-defined interfaces and modules allow small and large manufacturers to compete through performance of novel capabilities and enable the integration of new capabilities on a more frequent basis (Hinton et al. 2011).