Procuring Interoperability: Achieving High-Quality, Connected, and Person-Centered Care (2018)

Chapter: II. Interoperability in the Health Ecosystem

II.

INTEROPERABILITY IN THE HEALTH ECOSYSTEM

INTEROPERABILITY CONCEPTS AND TIERS

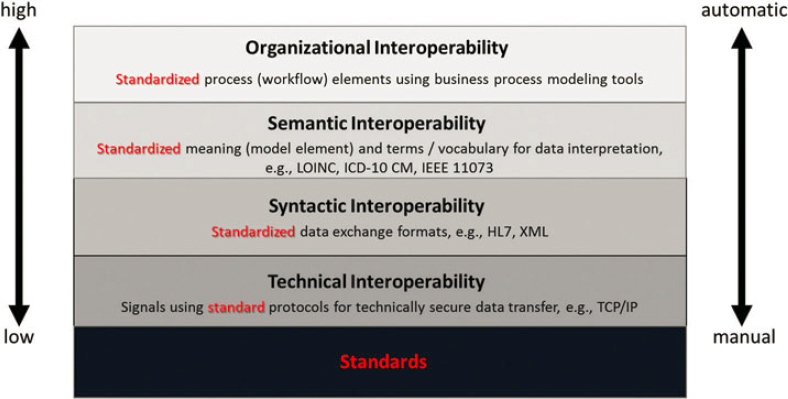

There are different aspects to interoperability, requiring different facilitative specifications depending on the interface, character, and needs. In addition to technical interoperability, in which standardized protocols are used to allow secure data transfer from one machine to another, the elements of syntactic, semantic, and organizational interoperability afford further interface functions to allow information to be exchanged and understood, and to inform (see Figure 4).

SOURCE: Based on Oemig F., and R. Snelick. 2016. Healthcare interoperability standards compliance handbook (p. 13, Figure 1.3). Switzerland: Springer.

NOTE: Data exchanges on the low technical level require more manual intervention to achieve the desired communication of meaning; data exchanges on the higher levels use more sophisticated standards, are more automatic, and require less manual intervention.

Syntactic interoperability brings standardized formats, such as the segments and elements in the HL7 Version 2 (v2) standard, for organizing the data in messages being exchanged. Specific kinds of data populate agreed-upon locations in the messages; for example, in an HL7 v2 laboratory results message, the third element of the observation/result (OBX-3) segment contains the identity of the lab test performed.

Semantic interoperability further enables more complete and specific data exchanges because an agreed-upon standard terminology is used by the data exchange partners. In the case of the lab test performed, the universal coding system LOINC (Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes) can be used to identify the lab test via a unique code name. For example, if the LOINC code 806–0 is in the third element of the OBX segment (OBX-3), the receiving system can automatically identify the test (i.e., leukocyte in cerebral spinal fluid by manual count) and process the rest of the message as the result of the leukocyte count.

Organizational interoperability involves the automation of workflow based on standardized business processes. In an HL7 v2 laboratory results message, for example, the eighth element of the OBX (OBX-8) segment indicates whether the result of the lab test performed is abnormal. If this element flags that the test result is outside of the normal range based on an agreed-upon clinical model, this flag can trigger a behavior in the receiving system, such as displaying an alert to the clinicians or ordering a follow-up lab test automatically.

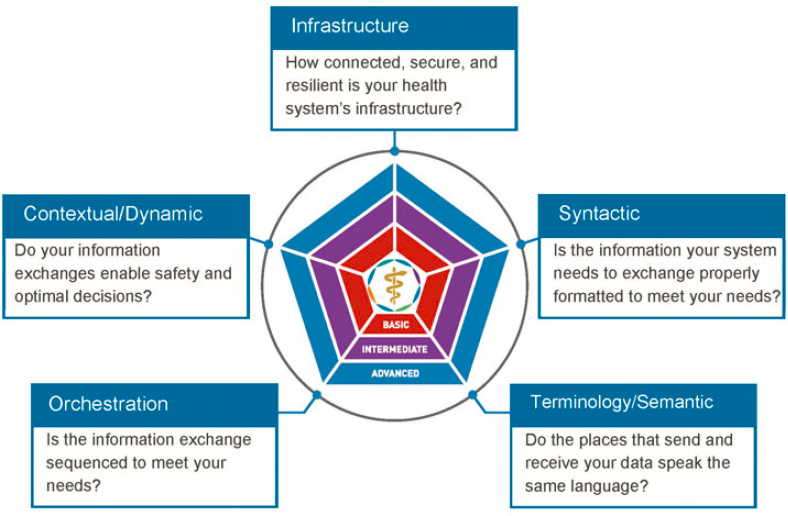

When considered from the perspective of a health care delivery organization, Figure 5 provides a conceptual model developed by William Stead from Vanderbilt University Medical Center and the Center for Medical Interoperability for assessing the maturity of data liquidity across multiple domains of interoperability. In this assessment, health system executives may assess organizational interoperability and data liquidity status by applying these five questions:

- Is the information your system needs to exchange properly formatted to meet your needs?

- Do the places that send and receive your data speak the same language?

- Is the information exchange sequenced to meet your needs?

- Do your information exchanges enable safety and optimal decisions?

- How connected, secure, and resilient is your health systems infrastructure?

Building on existing concepts of interoperability, the scope of interoperability covered in this report is holistic and based on the thesis that when interoperability is enabled throughout multiple levels in the health care ecosystem, the value of health technology investment can be maximized. Interoperability means the

SOURCE: Center for Medical Interoperability, 2016.

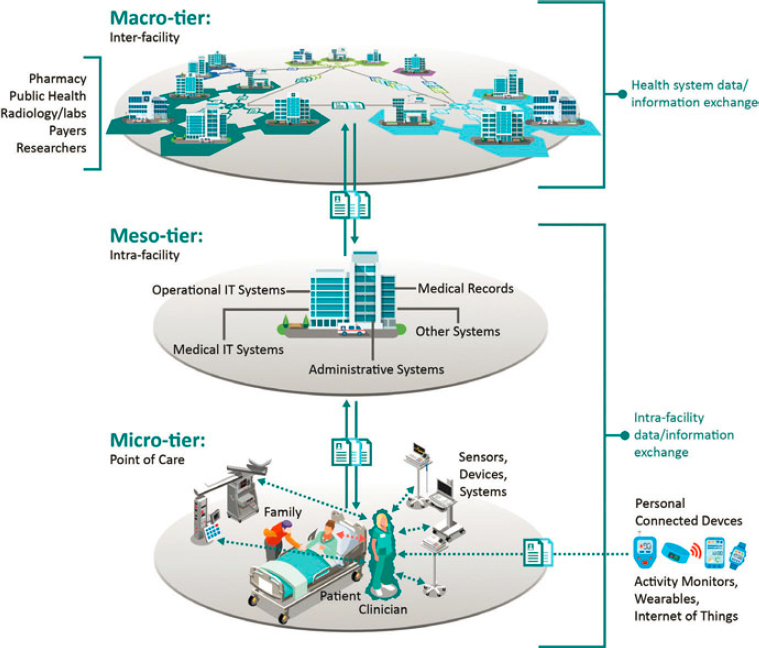

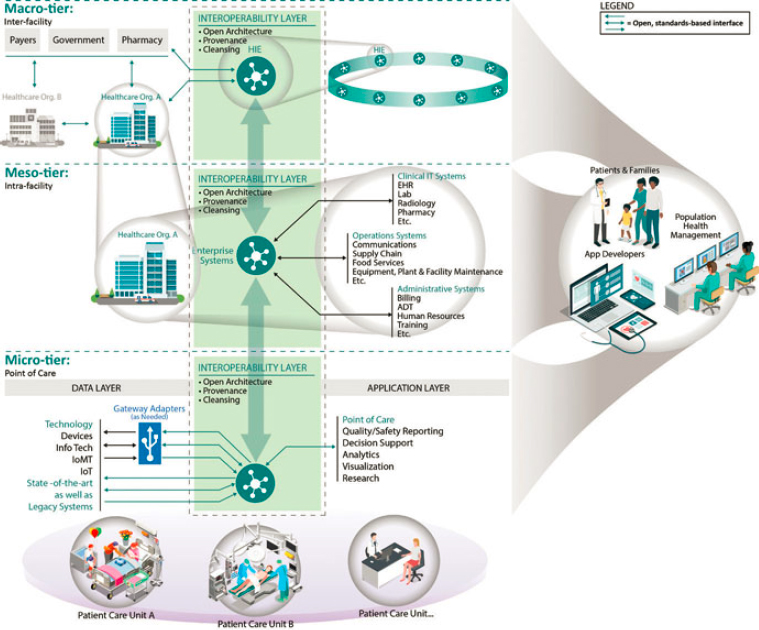

ability to share, abstract, or link data from electronic health records, medical equipment, registries, laboratory results, records from prescriptions, and specialist consultations, as well as administrative and claims records, patient portals, even wearable and mobile devices. Figure 6, Panel A portrays the functional interoperability required across the three tiers: inter-facility (macro-tier), intra-facility (meso-tier), and point of care (micro-tier) in the health care ecosystem. It is important to note, however, that the three-tier structure represents an organizing schematic with some distinct features and stakeholders within each tier. In practice, data exchanges do and should occur across tiers. As the fully interoperable system envisioned in Figure 6, Panel B, interoperability needs to encompass all tiers to enable whole-person and whole-community care—(e.g., supporting population health management, data access by patients and families, and third-party application development, to name a few).

To illustrate the importance of all three tiers, consider a scenario where a patient is involved in a car accident. She is taken to the nearest county hospital and then needs to be transferred to a trauma center to undergo emergency surgery. The trauma center dispatches its ambulance to transport the patient. While en route, she experiences cardiac arrest. Even though the trauma center and the county hospital use different EHR vendors, the transport team and the trauma

center are able to immediately obtain initial assessments, treatments, and imaging data. Meanwhile, the trauma center staff can see vital sign data from the ambulance in real time. Once the patient arrives at the trauma center, information from a variety of medical and monitoring devices is seamlessly integrated with information from the county hospital and displayed on a visual dashboard for the entire care team.

Or consider a health care system that has been increasingly engaged in value-based contracts with various payers through bundled payment or other

Panel A. Tiers at which interoperability is required

NOTES: Despite some progress at the macro-tier, many providers still rely on paper or fax to some extent to exchange information with another facility and in cases where the data is exchanged digitally, it is often in CCDA format - an electronic replication of paper forms—which can be difficult for receiving clinicians to understand the patient’s longitudinal care history. Within facilities (meso-tier) and at points of care (micro-tier), significant portions of data exchange depend on manual entry by clinical staff, which can adversely impact the timeliness, completeness, and accuracy of the data. Components of the health IT systems and healthcare devices may utilize proprietary interfaces to communicate or cannot automatically interoperate at all. There are very limited automated exchanges with personal connected devices.

SOURCE: Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Lab, 2018

shared-risk programs. A care team designated to optimize care management for patients with diabetes needs to draw data from multiple record systems within the organization to monitor their hemoglobin A1c testing and control status, making sure the patients receive annual retinal examination, achieve blood pressure control, and receive medical attention for signs of nephropathy. They will also need data automatically integrated from multiple devices when the patients visit their primary care physicians, ultimately allowing patients to upload their own data from their mobile devices. Members of the care team can receive notifications nearly in real time when a patient is admitted to the

NOTES: Fast, secure, and seamless exchange of meaningful information for clinical decision making, care coordination, and patient engagement at the macro-, meso-, and micro-tiers. Through a standards-based, open architecture interoperability layer, care history and clinical workflows can be optimally integrated to support timely, seamless care. At the macro-tier, data exchanges across care providers, public health and social services allow patient-centered continuity of care. At the meso-tier, integrated IT infrastructure allows efficient workflow integration and risk management. At the micro-tier, connectivity through non-proprietary interfaces supports modular upgrades to plug-and-play components, as well as augmental in-person clinical encounters with telemedicine, mobile health technology, and patient portals. Across all tiers, open application programming interfaces (APIs) provide access to web and software developers to build tools that enable individual engagement and population health management.

SOURCE: Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Lab, 2018

emergency department (ED). In addition, care coordinators rely on data shared from various external partners—ranging from pharmacies to behavioral health providers and social services agencies that serve the same patients—to provide high-value, high-quality, coordinated, and timely care. Figure 6B portrays this evolving state of interoperability, and related descriptions of the three tiers are described below and summarized in Table 1.

INTER-FACILITY (MACRO-TIER) INTEROPERABILITY

The macro-tier, illustrated in the top portion of Figure 6, represents health data exchanges across health care systems or between a health system and another entity such as a pharmacy or public health agency, some of which occur via regional or state-level Health Information Exchanges (HIEs) or an industry-wide network such as the Sequoia Project and the CommonWell Health Alliance. Over the past few years, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act and the Electronic Health Record Incentive (also known as the Meaningful Use) programs provided incentives to advance the basic ability to share data across health care systems. Information at this level is typically shared through the Clinical Document Architecture (CDA) framework, which enables clinical documents to be structured in a way that allows them to be read by both humans and computers.

Within each provider organization or health system, patient records are collated and made accessible through a centralized data aggregating and distribution entity (i.e., HIEs) and then shared across systems through information exchange gateways. Significant progress has been made in this tier, but the most recent data found that less than 30 percent of hospitals were able to find, send, receive, and integrate electronic patient information from outside providers (Holmgren, Patel et al., 2017). This means sizable challenges still exist: patient matching or identity management, fragmented records from multiple providers, attribution of the physician, and the potential for redundancy represent some of the usability and quality issues associated with data passed through the macro-tier. Providers and payers are also discovering new challenges in exchanging data outside the health care sector as they strive to address population health.

Here are three examples of macro-tier data exchange that are currently in play, though with significant gaps:

- Intervention linkages. In an effort to curtail prescription drug abuse, many states now employ a prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP), which tracks the prescribing and dispensing of controlled drugs such as opioids. Some HIEs also serve as an access point and data steward for interstate PDMP data

- Enterprise EHRs. Obstetrical patients will typically see a clinician (e.g., physician or nurse midwife) in an ambulatory/office setting, deliver in a hospital or a freestanding birthing center, and return for postpartum care in the clinical office setting afterward. Depending on the health care system environment, these visits may be documented both within and outside of the enterprise EHR. Additionally, when an obstetrical patient encounters illnesses, injuries, or complications of pregnancy while traveling away from her primary location, it requires transmittal of laboratory and/or imaging studies along with clinical information and notes to properly inform her care.

- Pooled data. Many integrated health systems use a population health approach to prevent avoidable admissions or ED visits and to manage total cost of care. They partner with payers to unify claims and clinical data to drive population health insights at the point of care. These systems can benefit from the knowledge of any unplanned visits outside the health system (EDs or urgent care clinics), whether patient prescriptions were filled (from any pharmacy), whether patients with hypertension are achieving adequate control (measured in any clinic or community setting or even at home), whether patients received flu shots, patient-reported pain and activities after surgery, and many other clinical events.

sharing, as well as managing access from public health agencies and behavioral health providers.

INTRA-FACILITY (MESO-TIER) INTEROPERABILITY

The meso-tier in Figure 6B represents interoperability within a health care organization, in which information was exchanged between an EHR and other information management systems such as those used in clinical laboratories, pharmacies, food services, facility management, and patient administration (admission/discharge/transfer). Interoperability at this tier facilitates the operational workflow and coordination throughout the entire episode of care, supporting both clinical and administrative activities with a coherent picture of the patient’s care processes and condition over time. Ensuring data elements are consistent across these systems not only reduces administrative burden but also improves patient experience with their care.

Currently, many hospitals procure locally hosted technologies such as pharmacy, laboratory, and other systems that enable varying degrees of integration with their respective EHR system. Some hospitals also acquire component technologies that aggregate data from these disparate IT systems before funneling that data to their EHR system for documentation of services and other purposes. Whether

intra-facility interoperability is driven by individual health systems or through partnerships, the ability to exchange data among different health IT modules is typically provided through vendor-to-vendor agreements. Integration based on numerous unique, stand-alone agreements requires significant resource investment, technical expertise, and maintenance over each IT module’s life cycle. This approach typically is not scalable, is costly, and is not sustainable as a long-term solution for the industry.

The following examples illustrate the value of enhancing meso-tier data exchange:

- Several hospitals deploy a central “command center” to monitor, streamline, and improve care efficiency. The dashboard used by the service- or system-level leadership requires linking a number of information management systems to provide a concise visual display of ambulance data, emergency department volumes, wait times, and bed status (full, empty, clean, and so on). In some instances, patient data from physiological monitors can be aggregated to provide predictive analytics to alert clinical staff about patients who may be under imminent risk for clinical deterioration. This information helps hospitals’ managers reduce capacity uncertainties and optimize the efficiency of personnel and facility resources.

- A regional hospital system with a network of several tertiary care hospitals, specialty hospitals, and a dozen community-based facilities sought to streamline their required quality reporting activities across multiple governmental and private payers, meanwhile improving their quality measures and rankings. Using myocardial infarction outcomes as proof of concept, the head of the cardiology service requests weekly reporting of several core quality metrics pertaining to patients undergoing various forms of procedures: in-hospital mortality, readmissions, secondary prevention, and patient-reported outcomes. Until recently, much of the reporting was done manually. With enhanced interoperability across various systems within the organization, relevant data can now be automatically pulled from EHRs, ADT (admissions/discharge/transfer) records, lab systems, pharmacy, and radiology to populate an electronic quality and outcomes report on a weekly basis.

POINT-OF-CARE (MICRO-TIER) INTEROPERABILITY

The micro-tier represents the data and information exchanged at the point of patient care (Figure 6)—whether at a particular care site (e.g., equipment and monitors in an intensive care unit) or generated by patients themselves (e.g.,

wearable or mobile health applications). Interoperability within this tier has great potential for improving patient safety, reducing medical errors, and reducing costs; it is also the level at which health systems have significant control and accountability through their procurement processes. At the point of care, data streams may be quite disparate and heterogeneous, ranging from verbal communications to medical record entries, device settings, image data, traditional laboratory results (e.g., blood type), and nontraditional data such as genomics and other patient-specific data. As with the other tiers, the data can consist of a combination of structured data, unstructured data, free text, and verbal communications.

Currently, micro-tier data exchange still largely relies on clinical staff (Figure 6, Panel A). Data generated by a medical device that are not exported to other systems means clinical staff must interpret the data, manually transcribe relevant values into the medical record, and possibly initiate an adjustment to the course of treatment. Transcription errors are common; one study found an error rate as high as 19 percent when clinical staff manually transcribe vital signs onto paper and then subsequently enter them into EHR (Fieler et al. 2013). In comparison, the use of electronic vital signs documentation systems resulted in significantly fewer errors and shorter elapsed time. The lack of true interoperability at the point of care, coupled with the advances in medical technologies that make clinical decision making increasingly complex, puts a tremendous burden on providers and poses great risk of medical errors and eventually, patient harm.

For example:

- A cancer patient’s patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) pump was programmed to maintain a low constant infusion rate of opioid but also respond to inputs from the patient. Currently, clinical staff would manually program the PCA pump while periodically monitoring combined dosage and pulse oximetry readings to detect potential respiratory depression. In the event of respiratory depression, staff would manually discontinue the infusion. An improved state of interoperability could include a PCA safety interlock that allows signals from a vital signs monitoring device to trigger a stop of the opioid infusion at the onset of respiratory depression.

- An academic health center sought to implement a number of “checklists” to prevent common harms experienced by intensive care unit patients, including harm from receiving disrespectful care and harm from receiving care that is not consistent with patient goals. Even though algorithms exist to predict a patient’s risk for certain types of harm (e.g., based on vital signs, care history,

disease severity, and comorbidity), available technology has not provided an automated visual display of the conformity of a care regimen to recommended protocols. To fill this gap, researchers at Johns Hopkins Medicine (Romig, Tropello et al., 2015) used a systems engineering approach and developed a technology platform that integrated a variety of data elements from the EHR and from other sensor devices, which then graphically displayed the data on a tablet in real time to trigger and monitor the implementation of patient harm prevention measures.

TABLE 1 | Definitions, applications, and the current state of interoperability

| INTER-FACILITY EXCHANGE (MACRO-TIER) | INTRA-FACILITY EXCHANGE (MESO-TIER) | POINT OF CARE EXCHANGE (MICRO-TIER) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Definition | Exchange of information among organizations and networks. | Exchange of information among care units within an organization or network, including operations and administrative IT systems. | Point-of-care exchange at which care devices, equipment, records, and clinical staff interact with patients. |

| Example Clinical Applications | Continuity of care across different providers and types of facilities (e.g., providers in different geographical areas, multiple pharmacies); population health management in accountable care models through addressing medical, behavioral, and social needs; information exchange with public health agencies. | Consolidation and automatic exchange of patient records across laboratory and radiology with EHR; data exchanges among scheduling, billing, quality reporting, and care delivery IT systems; continuity of care across facilities within the network (e.g., outpatient clinics, EDs, in-patient services, and postacute care facilities). | Automatic data exchanges from bedside monitors to the EHR; programmable infusion pumps with safety interlock that allow signals from patient vital signs monitors; postdischarge patient monitoring through wearable devices. |

| Current State | Some progress in data exchange standards, regional HIEs, and direct exchanges across providers. Challenges remain in workflow integration. | Some progress through software interfaces, but manual handling and duplication of records are common. | Clinical staff performs the majority of data exchange. Adoption of custom middleware solutions to enable connections between two proprietary interfaces. |

| Future State | Fast and secure data exchanges across care providers; coordinated data aggregation across clinical, behavioral health, public health, and social service agencies in support of population health management; access and control by patients for their own care record. | Integrated IT infrastructure within the health care provider systems that allow seamless application of risk management analytics, workflow integration, quality improvement and reporting, and cybersecurity protection. | Integrated patient care devices and IT system based on open architecture connectivity and nonproprietary standards; modular upgrades to plug- and-play components and devices as needed; integrated telemedicine capabilities, connected mobile health technology, and patient portals to augment in-person clinical encounters. |

Currently, medical device vendors lack the market imperative to ensure interoperability, partly because providers bear most of the costs of integrating these devices and because there is an absence of an aligned demand to drive change in the technology ecosystem. Some health care providers achieve some level of medical device integration, particularly to support data to EHR integration. However, in the perceived absence of a prominent value proposition, many devices are not integrated with other technologies at all. Although it is unlikely that medical device and IT vendors will spontaneously and proactively move toward standardized “plug-and-play” device interoperability, clearly clinicians have significant motivation for demanding medical device data liquidity and interoperability. Solutions are urgently needed to address the efficiency, capacity, and cost issues faced by health care providers under the pressure to shift toward value-based payment models.

CURRENT STATE IN PRACTICE

The community of health IT vendors has evolved primarily into two categories: companies that support the ambulatory market, and those targeting the hospital market. There was initially little crossover between these two groups, but more recently, vendors have moved toward providing health IT solutions capable of functioning in both domains. Health IT solutions for the in-patient setting are more complex, and far fewer vendors service that market, which is dominated by Epic Systems, Cerner, and MEDITECH. The market is also segmented by size and complexity; academic medical centers and large integrated delivery networks select vendors that are different from those selected by small critical access hospitals. For smaller or independent practices, less expensive or less resource-intensive platforms such as athenahealth and eClinicalWorks lead in market share. This breakdown is evolving, however, as large EHR vendors have been retooling their offerings to be more competitive in different market segments.

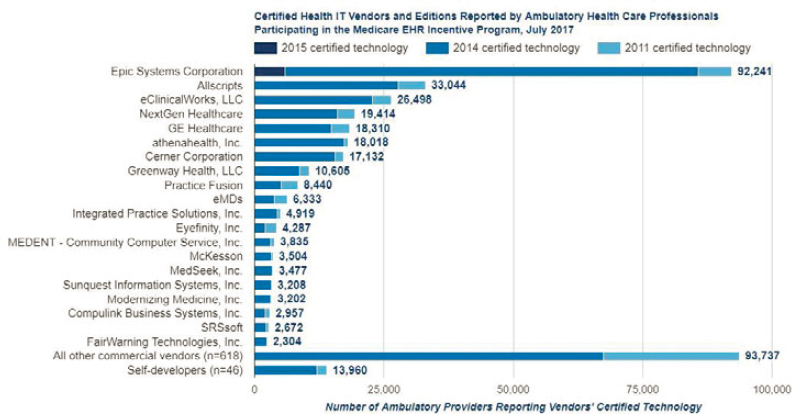

In contrast, as indicated in Figure 7, the ambulatory market is characterized by a much larger number of vendors (684 as of July 2017) with Epic again demonstrating significant market share, followed by Allscripts and eClinicalWorks. Nevertheless, the amount of consolidation and the number of developers leaving the market is increasing. This trend creates difficulty for individual physicians and small practices that lack the infrastructure support to make transitions to an alternative vendor, which can be time consuming and costly, and provide an opportunity for clinical errors. Of note, recognizing the need, the ONC developed technical support resources targeted at smaller providers within its Health IT Playbook

(Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology,) and the EHR Contracting Guide (Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology, 2016). Finally, an increasing percentage of users are choosing to have their data hosted in a secure cloud by their vendors. The vendor provides the security, infrastructure, backup, and maintenance of the software and data that many find difficult to manage in small practice settings. In addition, cloud-based technologies are much easier and less costly to update.

Certified Health IT Developers and Editions Reported by Ambulatory Primary Care Physicians, Medical and Surgical Specialists, Podiatrists, Optometrists, Dentists, and Chiropractors Participating in the Medicare EHR Incentive Program

SOURCE: Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT. July 2017. https://dashboard.healthit.gov/quickstats/pages/FIG-Vendors-of-EHRs-to-Participating-Professionals.php.

With broad recognition of the importance and value of interoperability in health care, various governmental and industry entities have collectively made progress across all three tiers of interoperability. What follows are some exemplary national and consortium efforts:

- A 2005 report by the Commission on Systemic Interoperability identified a set of 14 recommendations in a multidimensional approach to achieve connectivity, privacy, and security (Commission on Systemic Interoperability, 2005).

- A 2009 consensus study by the National Research Council advocates rebalancing the portfolio of investments in health care IT to provide greater support for health care providers, patients, and family caregivers as well as observing

- A 2010 report by the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology (PCAST) issued the first clear statement that interoperability needed to be designed into the technical infrastructure from the beginning, in contrast to an ad hoc effort at the interface between components (President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology, 2010).

- Funded by the ONC, a 2013 report by the independent JASON advisory group highlighted the lack of an architecture supporting standardized application programming interfaces (APIs), as well as EHR vendor technology and business practices, as structural impediments to achieving interoperability (JASON 2013). The report recommended a centrally orchestrated interoperability architecture based on open APIs and advanced intermediary applications and services. The 2014 JASON Task Force report affirmed such an architectural approach and further mapped existing standards to the architecture (JASON Report Task Force, 2014).

- Integrating the Healthcare Enterprise (IHE) is an initiative started in 1997 by health care industry professionals with the initial goal of improving the integration of imaging data into hospital IT infrastructure. Since then, IHE has expanded its scope to include multiple functional domains (e.g., laboratory, cardiology, and pathology), which create specific integration profile documents and provide guidance on the coordinated use of established standards such as Digital Imaging and Communication in Medicine (DICOM) and Health Level Seven International (HL7) (Rhoads, Cooper et al., 2009).

- The Medical Device Innovation Consortium (MDIC) is a public-private partnership formed in 2012 to advance medical device regulatory science for patient benefit. Its membership includes representatives of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), National Institutes of Health (NIH), Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), industry, and nonprofits and patient organizations. In addition to developing regulatory science tools to support clinical trial innovation and incorporating patient engagement, MDIC also established the National Evaluation System for health Technology (NEST) coordinating center to enhance interoperability efforts by making device data available.

- The Center for Medical Interoperability (CMI) is a nonprofit organization founded in 2013 as a cooperative research and development lab. CMI membership is limited to health systems, individuals, and self-insured corporations but works with a variety of stakeholders. CMI aims to provide centralized engineering resources in enabling vendor-neutral, plug-and-play interoperability

proven principles for success in designing and implementing IT to advance patient safety (National Research Council, 2012).

- ONC Interoperability Standards Advisory: First established in 2015 and updated annually, the ONC interoperability standards advisory provides guidance on “best-of-breed” data exchange standards, integration profiles, and implementation guides based on intended purpose (i.e., use cases), maturity, and degree of adoption. Although the advisory’s structure and content is most amenable to aiding system and device developers in solving specific data exchange issues, it is a useful reference for interoperability “customers” working to develop procurement specifications.

- The Argonaut Project is a private-sector initiative to advance industry adoption of modern, open interoperability standards. The purpose of the Argonaut Project is to accelerate time to market by developing a first-generation Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR)-based APIs (see Appendix, Box A1-3) and Core Data Services specification to enable expanded information sharing for EHRs and other health IT. This effort follows on recommendations from the JASON Task Force Report.

- Since 2012, the nonprofit Sequoia Project organization has taken over the management of the eHealth Exchange, now the largest health information exchange network in the country. The Sequoia Project also operates the Carequality initiative, which facilitates technical and policy agreements to enable nationwide interoperability among diverse representatives of payers, EHR vendors, accountable care organizations, record locator service providers, and other existing networks. The Carequality interoperability framework provides the legal terms, policy requirements, technical specifications, and governance processes to bridge networks and services. In parallel, CommonWell Health Alliance is a nonprofit trade association of health IT companies to create universal access to health data. In 2016, CommonWell and Carequality announced enhanced collaboration and expanded connectivity, with an immediate focus on extending providers’ ability to request and retrieve medical records electronically. Together, the CommonWell framework and Carequality network represent more than 90 percent of the acute care EHR market and nearly 60 percent of the ambulatory EHR market, including 15,000 hospitals, clinics, and other health care organizations. Both Sequoia and CommonWell partner with the Argonaut Project to enable more comprehensive FHIR-based exchange at scale.

- The 21st Century Cures Act was enacted in December 2016 and, in part, included provisions to enhance interoperability and eliminate information blocking, defined broadly as a “practice that . . . is likely to interfere with,

in the form of specifications, software reference implementations, and an interoperability testing and certification program.

prevent, or materially discourage access, exchange or use of electronic health information.” The act calls for, “without special efforts,” open APIs based on modern standards such as JSON and FHIR. In addition, the act requires the federal government to develop a Trusted Exchange Framework and Common Agreement (TEFCA) to provide a single “on-ramp” to nationwide interoperability while achieving a competitive, sustainable market (114th Congress, 2015).

Taken together, these milestone efforts pave the way toward better interoperability on several fronts: the development of data exchange standards, promoting open API, combating information blocking, building data partnerships with the social services sector and public health, embracing open platform and exchange capabilities at the delivery system level, and integrating claims, EHR, and pharmacy data.

This page intentionally left blank.