Procuring Interoperability: Achieving High-Quality, Connected, and Person-Centered Care (2018)

Chapter: Technical Supplement - Section 1: Implementation Strategy for Purchasing Interoperable Systems

Technical Supplement—Section 1

IMPLEMENTATION STRATEGY FOR PURCHASING INTEROPERABLE SYSTEMS

Procuring interoperable solutions requires a common understanding of the terms interoperability and openness. In the context of health information technology, the 21st Century Cures Act defines “interoperable” information technology as that which “(A) enables the secure exchange of electronic health information with, and use of electronic health information from, other health information technology without special effort on the part of the user; (B) allows for complete access, exchange, and use of all electronically accessible health information for authorized use under applicable State or Federal law; and (C) does not constitute information blocking” (21st Century Cures Act, H.R. 34, 114th Congress, 2016). This definition highlights the benefit of shared information, implying that the automated exchange of data reduces human workload and the potential for errors associated with manual data transactions. Achieving an effective interoperability implementation is a complex process dependent on not only data quality, usability, security, and privacy but also culture, governance, and infrastructure. Effective interoperability enables organizations to achieve meaningful goals that include improved outcomes, fewer patient harms, and overall improved value.

System interoperability can imply a desire for system “openness.” In an open design—often referred to as open architecture (OA)—one subsystem can be replaced with minimal effect on other subsystems as long as the replacement meets the open architecture specifications. For example, a hospital can replace or upgrade its laboratory information system (a subsystem) to a different vendor without affecting other subsystems such as the pharmacy, billing, or EHR. In the most successful open architecture applications, exchanging one subsystem for another has no effect on system integration. A full or partial open architecture implementation has the potential to ease integration workload and costs associated with replacing or upgrading a system or subsystem. Consequently, individual subsystems can be upgraded on a more frequent basis, enabling managed obsolescence and new capability insertion (DoD Open Systems Architecture Data Rights Team, 2013).

One means by which to increase system openness is adherence of connected subsystems to an interface standard and a well-defined open architecture setting the foundation for an open business model where organizations compete in the procurement process based largely on the performance and cost of their individual products (or subsystems) rather than on how information is exchanged between subsystems. (Section D describes how the US Navy transformed its procurement approaches for submarines and robotics, respectively, into open business models.) Most efforts at improving openness in health care systems to date have focused on adoption of standard health data and information interfaces, and there have been efforts to provide guidance for interoperability-related contract language (MD FIRE, 2017; SMART on FHIR, 2017; Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT, 2016; Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT, 2012) but more progress is needed.

The modular open system architecture (MOSA) approach realizes the full potential of OA. In MOSA, standardization goes beyond subsystem interfaces. A MOSA specification represents a system as a framework of interconnected modules where each module’s interfaces, essential functions, and performance characteristics are clearly specified. A personal computer is an example of a MOSA implementation where the mouse, display, and keyboard are modules that must comply with certain essential requirements to achieve plug-and-play capability. Vendors competing to supply a particular module can offer unique features and cost savings to differentiate their product from competitors, but their product must comply with MOSA specifications.

Note that two subsystems can be interoperable (i.e., they can exchange information and use that information) and not be “open” as defined above. For example, a single subsystem supplier may use a nonstandard proprietary interface to connect with another subsystem. In this case, the two subsystems may be interoperable; however, if one subsystem is replaced with a subsystem from an alternate vendor, the legacy system must be modified to accommodate the different interface of the replacement. Consequently, replacing one subsystem might necessitate significant and costly modifications of the other. Herein, the use of the term interoperability also assumes the desire for openness.

INTEROPERABLE HEALTH CARE TECHNOLOGY PROCUREMENT FRAMEWORK

Using procurement to drive advances in interoperability across the industry requires synergy of health care organizations on a common procurement framework. Across many diverse, geographically dispersed, independently owned,

and commercially developed health care systems and devices there is no single overarching authority or government entity that coordinates, controls, and funds the comprehensive changes required to achieve interoperability across the entire health care system. The government plays an important role in portions of the landscape, establishing guidance, policy, regulations, and funding development of interoperability enablers such as health data exchange standards. Even so, the hard work and resources needed for success falls to enlightened hospital executives and staff, forward-thinking health care system and device suppliers, and many others as part of a coalition of the willing.

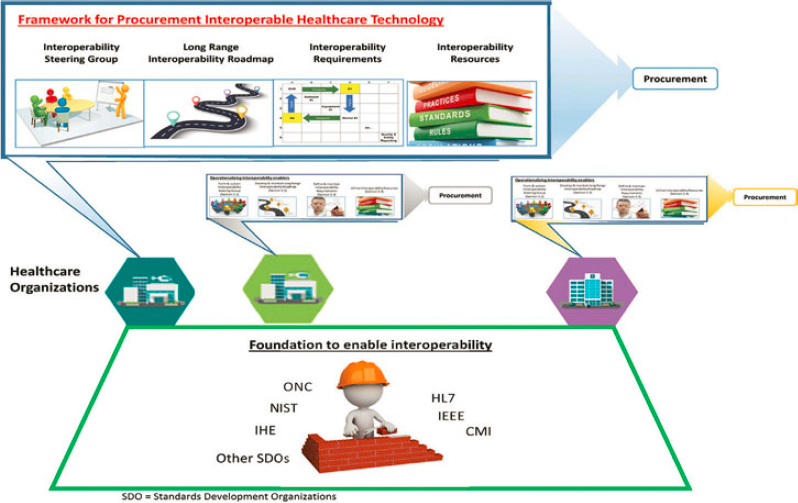

There are no effortless solutions to achieving interoperability. Long-term vision, leadership commitment, a technical knowledgebase, and, perhaps most of all, persistence will be required for a health care organization to make progress. At the same time, numerous organizations have made great strides in the field of interoperability, which can be used to both make the individual hospital’s task easier and move the industry forward. Figure A1-1 shows the common foundation from which each hospital can build their procurement strategy. That foundation comprises work done by organizations such as the Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT (ONC), the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), Integrating the Healthcare Enterprise (IHE), Health Level Seven International (HL7), Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), the Center for Medical Interoperability (CMI), and others.

SOURCE: Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Lab, 2018

Although this foundation is available, health care organizations may not consistently specify their approach and RFP language clearly to realize the benefits of interoperable and open systems. To drive the industry toward interoperability, each health care organization (represented by the colored hexagons in Figure A1-1) must align four primary elements of a procurement framework. These elements, illustrated in Figure A1-1 are as follows:

- An interoperability steering group: A group within each health care organization that develops strategic guidance on interoperability through setting priorities, coordinating, and overseeing IT acquisition activities across the organization. This steering group could be established anew or be formed within an existing steering committee overseeing the IT infrastructure and/or procurement. In addition to leading interoperability transformation within the organization, the group represents the organization in collaborating with other organizations throughout health care on resource sharing and collective learning.

- Long-range interoperability road map: A multiyear procurement plan that describes incremental objectives for improving interoperability and system openness.

- Interoperability needs identification process: The documentation and visualization of the complex information and workflow interactions in a health care setting, and the translation of these to interoperability needs for new or upgraded health care systems.

- Interoperability procurement specification process: The translation of interoperability needs to procurement specifications in RFPs leveraging various health system data exchange standards and supporting resources.

The resources produced through multiorganizational collaborations should be a shared resource across the field. In many cases, however, local tailoring of these resources will likely be required, since not all organizations or facilities are identical in terms of their care for patients, policies, procedures, and procurement priorities. Also described in Figure A1-1 is the role of the industry. Health care organizations and facilities will use the public domain resources produced by the interoperability steering group to procure interoperable solutions from industry. Accordingly, the industry must conform to the policy, standards, and profiles that form the foundation for interoperability.

INTEROPERABILITY STEERING GROUP

A senior level, CEO-mandated interoperability steering group is central to the organization’s governance infrastructure to enhance interoperability and optimize the organization’s investment in health IT acquisition (Selva and Katz, 2017). The interoperability steering group will ideally be a standing organizational committee supported by and accountable to the health care organization’s top leadership. While some organizations may form a new standalone steering group, others may appoint a team of related capacity within their existing purchasing steering committee structure. Nevertheless, this senior-level committee serves as the “organizational champion” that motivates, oversees, coordinates, and periodically evaluates the procurement framework. This group should work with diverse stakeholders across the organization—including clinical departments (e.g., cardiology, emergency department, pathology, and so on), clinical/biomedical engineering, hospital administration, billing and revenue operations, and IT—to provide coordination and reduce fragmentation and silos. For example, this group can curate common interoperability specification languages that are consistent with the organization’s visions, missions, and target outcomes. This group also serves as a liaison in participating in external consortium efforts to drive industry-wide interoperability.

The responsibilities of the interoperability steering group may vary by organization but should include the following:

- Work with stakeholders across the organization to identify common needs and workflow challenges, as well as unique service-specific circumstances related to data exchange requirements for care delivery;

- Develop concrete objectives and top priority clinical use cases regarding interoperability in the organization’s procurement processes, including the development of a long-range interoperability road map;

- Identify interoperability priorities and form implementation plans across the organization’s various procurement activities;

- Develop or curate common interoperability requirement language that may be used by multiple services and technology types, and oversee the adoption of best practices in procurement processes across the organization;

- Stay abreast of the latest advances in interoperability, data exchange standards, and industry-wide best practices across the macro-, meso-, and micro-tiers;

- Oversee the translation and customization of shared or open-source platforms or interoperability profiles to unique local contexts;

- Set performance metrics on progress over time and consistently measure them; and

- Represent the organization in external consortium efforts to promote information sharing, consensus building, and the establishment of common resources.

LONG-RANGE INTEROPERABILITY ROAD MAP

As described in earlier sections of this publication, health care organizations should have a multiyear procurement strategy, and this plan should include a road map that sets the vision for improving interoperability and system openness within the organization. The long-range interoperability road map provides guideposts for planned adjustment and/or transformation in the procurement practice that, over time, aims to move the organization closer to the vision.

This road map should be a living document based upon the best available information, adapting to both internal and external changes that influence procurement priorities of the organization. The interoperability steering group will develop the road map through engagements with stakeholders to understand their interoperability needs and identify opportunities to improve workflow and outcomes. To maintain visibility, focus, and relevance, the interoperability steering group should communicate the road map within the health care organization and continuously seeking feedback toward procuring interoperable solutions. Along with the organization’s multiyear procurement plan, the road map should be updated at least annually to keep pace with technological developments in the field as well as evolving organizational needs.

INTEROPERABILITY NEEDS IDENTIFICATION PROCESS

The interoperability steering group should engage their organization’s health care system stakeholders at least annually to identify needs and opportunities for making systems more interoperable and open, and subsequently to reflect them in updates of the interoperability road map. Note that this is more than a simple polling process. A single hospital unit includes many interactions between technology and staff; an entire hospital multiplies the number of interactions enormously. Comprehending and tracking all these interwoven and interdependent interactions can be daunting, yet understanding these relationships is essential to identifying interoperability needs and opportunities that drive a procurement

strategy. Because of this complexity, it is not likely that stakeholders will simply submit their respective lists of interoperability requirements; rather, the interoperability steering group must lead the stakeholders through a series of methodical design development exercises from which these needs can be distilled.

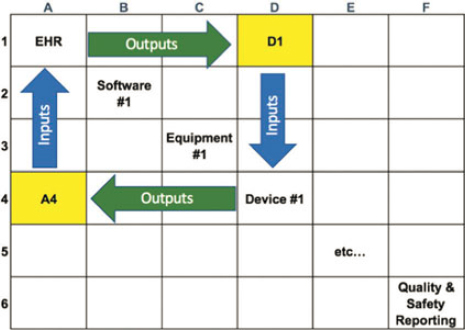

The field of engineering offers many diagramming tools that may help organizations grapple with their respective interoperability challenges. These tools include diagrams such as flowcharts, block diagrams, and technical illustrations such as the family of diagrams defined by Unified Modeling Language (Object Management Group Unified Modeling Language, 2017) or SysML (Object Management Group Systems Modeling Language, 2017). One of the tools routinely used by systems engineers in industries such as space and military system development is the N-squared diagram (Figure A1-2, and Technical Appendix Section B). It is a technique used to document complex interactions among hardware or software systems (NASA, 2007), and it can afford health care the same benefits.

For example, the interoperability steering group can work with relevant stakeholders within the organization to develop an N-squared diagram of a care unit such as an intensive care unit (ICU).

At the start, the table shown in Figure A1-2 would have all blank fields. The first step is entering the diagonal elements. These represent the entities (technologies, equipment, and people) that currently interact in the unit. The nondiagonal elements represent the interactions (including data exchange) between the various diagonal elements. By convention, any output of a diagonal element is identified in the row containing that element (shown by the green arrow). Any input of a diagonal element is represented in the column containing that element (shown by the blue arrow). Although there is no constraint on the type of interactions captured, a typical first step is to capture all manual (verbal and written) and electronic data transactions.

The process of developing the diagram motivates important discussions with stakeholders, including the following:

- Which processes currently rely most heavily on manual entry by staff, especially physicians and nurses?

- Which manually entered data fields have the greatest influence on care decisions and patient outcomes?

- Can any recurring data field (e.g., body weight, blood pressure, known allergies) be automated, thus minimizing manual entry or copying/pasting?

- Based on the nature of the data field, what is the level of data security and privacy protection needed?

- What are clinicians’ needs for data accessibility, timeliness, and refresh rates?

- Do the data fields need to be shared with other clinical or administrative departments and/or external entities?

- What is the estimated staff time and resource cost of manual data exchange?

Once the diagram is populated, the layout of the information can reveal interoperability needs and opportunities that were not previously obvious. Lining up interoperability needs highlighted in the diagram with the organization’s priorities informs the development of the Interoperability Road Map included in the organization’s multiyear procurement plan (Section 1). Technical Supplement Section 2 demonstrates the development of an N-squared diagram for an endoscopy suite as a representative example of how to use this tool.

SOURCE: Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Lab, 2018

INTEROPERABILITY PROCUREMENT SPECIFICATION PROCESS

As described earlier, a particular need for interoperability involves the exchange of digital information among health care technologies. To acquire open system solutions, the health care organization must require the supplier to implement the interface between the technologies according to industry-accepted health data exchange standards. As of 2017, commonly used standards include the HL7 standards for exchange between health information systems, the IEEE 11073 standards for patient care devices, the SNOMED-CT medical diagnosis codes, the RxNORM medication codes, LOINC for laboratory and other observation identifiers, and a host of other notable health care-related standards.

A data exchange standard specification can include multiple volumes of documentation, each having hundreds of pages of detailed technical information. Despite the term standard, it is often possible to apply or use a standard in a variety of different ways. Each vendor can interpret and develop a unique implementation of the standard to satisfy a similar purpose. Therefore, independent implementations of an interface that achieves the same purpose could be significantly different even while each complies with the same standard. Since open system solutions require identical or at least similar implementations, giving vendors latitude to use the standards as they choose leads to nonopen solutions industry-wide.

As a consequence, a health care organization must not only require candidate vendors to use particular data exchange standards for satisfying an interoperability need, but must also specify constraints on how the vendor is to implement these standards. Fortunately, organizations such as HL7 International, Integrating the Healthcare Enterprise (IHE), and Personal Connected Health Alliance (Personal Connected Health Alliance, 2017) have developed “guides” or “profiles” that provide instructions on how to implement various data exchange standards to satisfy different interoperability needs. Box A1-1 describes these integration profiles and implementation guides in more detail. In addition, the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology’s (ONC) Interoperability Standards Advisory (ISA) provides best-practice guidance on which data exchange standards, implementation guides, and integration profiles should be used (see description in Box A1-2).

Health care organizations of any size can leverage these resources in an organized fashion to translate their interoperability needs into procurement specification language. Consider the case in which a hospital requires a medical device to interface with the EHR system through a local network, thereby bypassing the need for manual data entry. The hospital’s Interoperability Steering Group determines that upgrades of the EHR system are needed to accomplish this. The Request for Proposal (RFP) to the EHR vendor would include this statement:

The EHR system shall be upgraded to be compliant to the IHE Patient Care Device (PCD) Technical Framework, specifically to the Device Enterprise Communications (DEC) Integration Profile. Within the DEC profile, the EHR system shall have the role of the Device Observation Consumer.

The language in this brief specification statement defines the interoperability need of the system, the data exchange standards to be used, and the constraints on how the standard should be implemented. Simple statements such as this can improve an organization’s ability to stipulate interoperability in their procurement specifications. In addition to specifying interoperability and openness as an overarching goal, a health care organization would typically also prescribe functional requirements for the technology they are purchasing.

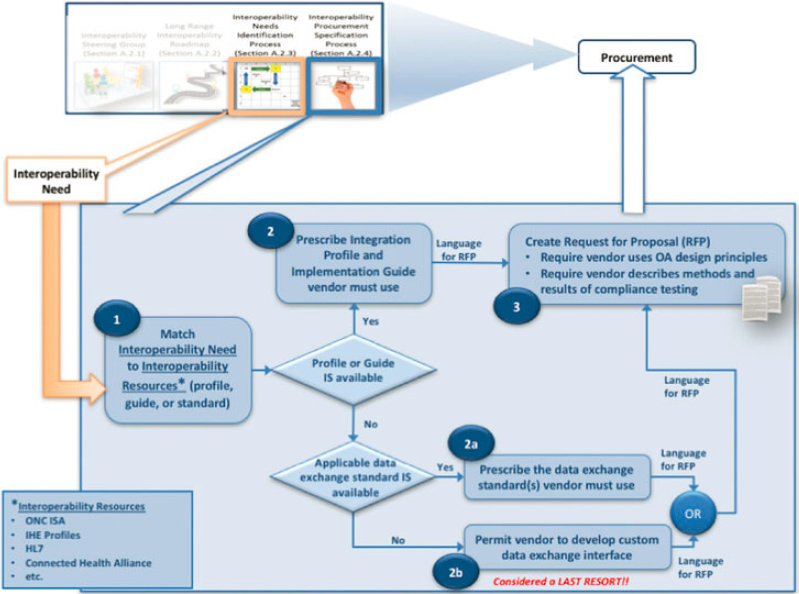

The interoperability steering group would work with the appropriate internal stakeholders to identify the information exchange needs. They can then provide guidance on the process of selecting data exchange standards, implementation guides, and integration profiles, and oversee the development of procurement specifications for new or updated systems or subsystems that must be interoperable with one or more other systems. Figure A1-3 shows the key specification development steps leading to interoperability content for an RFP described as follows:

Step 1. Match interoperability need to interoperability resources. To execute this step, the interoperability steering group would seek recommendations from the ONC ISA and would research available integration profiles and implementation guides.

If an integration profile and/or implementation guide that align with a specific interoperability need is identified, then:

Step 2. Prescribe the integration profile(s) and implementation guide(s) vendors must use. The result is a statement included in the RFP. Refer to Technical Supplement Section 3.

SOURCE: Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Lab, 2018

On the other hand, if there is no alignment between an interoperability need and a profile or implementation guide:

- Require vendor to describe methods and results of compliance testing. The health care organization’s proposal evaluation criteria should reward vendors who will perform best-practice standards and profile compliance testing.

a modular open system architecture is more likely to provide the basis for modular upgrades or new integration profiles.

Technical Supplement Section 3 describes examples of interoperability procurement language for several cases—(1) upgrade of a laboratory information system, (2) use-case-driven integration scenario in obstetrics, (3) integration of patient care devices with the EHR system, (4) request for specific functionality and interoperability capabilities or request for information, (5) modular open systems architecture language—that would result from following the process illustrated in Figure A1-3.

As a final note to this section, a health care organization’s effective use of integration profiles and implementation guides in writing specifications is a discipline that can result in more open commercial products that reduce overall integration costs for new or upgraded capabilities. That said, some of these guiding resources may lack adequate specifics, forcing developers to make some design decisions. This leaves open the possibility of subtle variations in developer implementations that challenge achieving the ideal of plug-and-play system openness.

INTEROPERABILITY PROCUREMENT CONSIDERATIONS AND GUIDANCE

Taking into account the current state of the industry, this section will address general procurement guidance and considerations at each of the three interoperability tiers. No matter what type of system is being purchased, it can be useful to include a declaration statement at the start of the RFP to affirm the need for interoperability and security, as well as any unique missions and relevant clinical contexts worth noting.

RFP interoperability declaration statement

A health care organization should include in all RFPs for its technology acquisition a declaration statement that affirms the organization’s commitment to seeking interoperable and open architecture solutions and favor vendors who offer those solutions. Even without further stipulation, the strength of many health care organizations making such statements may influence vendor business practices in a favorable direction. Such declarations also cultivate open-systems expectations and commitment within the organization. A sample declaration statement follows.

[Organization Name] is committed to promoting increased health system interoperability and openness, and, in our procurements, will favor vendors that support these objectives.

Specifically, [Organization Name] will favor vendors who apply open architecture best practices:

- Implement interfaces using best-practice data exchange standards, integration profiles, and implementation guides, and provide verification evidence of compliance of such;

- Provide full documentation disclosing interface design and functionality; and

- Provide full disclosure and breakdown of integration and test labor and costs.

Health care organizations can refer to the DoD Open Systems Architecture Contract Guidebook for Program Managers, v1.1 (DoD Open Systems Architecture Data Rights Team, 2013) which provides open architecture best-practice language that can be directly quoted or paraphrased in the introductory sections of RFPs. Technical Supplement, Section 3 provides excerpts from the guidebook.

Here is another example source for introductory texts that may inform the health care organization’s needs and motivations in procuring medical devices (MD FIRE Version 2.6, excerpt):

Objectives

We [Organization Name] intend to adopt and implement interoperability standards for medical device interconnectivity via our procurement actions. We also recognize that the necessary standards are not yet fully developed or widely implemented by medical equipment vendors. However, we believe that adoption of standards-compliant interoperable devices and associated systems (i) will enable the development of innovative approaches to improve patient safety, health care quality, and provider efficiency for patient care; (ii) will improve the quality of medical devices; (iii) will increase the rate of adoption of new clinical technology and corresponding improvements in patient care; (iv) will release health care delivery organization (HCDO) resources now used to maintain customized interfaces; and (v) will enable the acquisition and analysis of more complete and more accurate patient and device data, which will support individual and institutional goals for improved health care quality and outcomes.

Our goals are to (i) encourage the implementation of interoperability by compiling and presenting the evidence of present and projected clinical demand for the interoperability of medical devices; and (ii) encourage and facilitate the development and adoption of medical device interoperability standards and related technologies through HCDO procurement actions.

We are, therefore, including medical device interoperability as an essential element in our procurement process and in future vendor selection criteria.

CYBERSECURITY AND PRIVACY CONSIDERATIONS

Although interconnected systems afford great potential value, they can also lead to increased security-related risks if not properly mitigated (Palfrey et al. 2012). As in other industries, cybersecurity and privacy breaches can threaten trust and dampen willingness for data sharing. On the other hand, many legacy systems that operate in a silo have security vulnerabilities, and the system-of-systems environment may allow more shared resources devoted to assess risks and test mitigation and remediation strategies. In the context of the multitier model, it is vital to understand how interoperability may or may not affect the exposure, modification, and how these risks may be mitigated.

The NIST Cyber Security Framework (NIST, 2014) affords a tool leading to better understanding of the threat to interoperable health care systems, which tends to be secondary to other operational and functional requirements. To tackle security and privacy concerns, NIST’s framework can provide a structure for defining functional and nonfunctional requirements for the acquisition of health care systems and components. The NIST cybersecurity framework provides a mechanism for health care organizations to:

- describe their current cybersecurity posture,

- describe their target state for cybersecurity,

- identify and prioritize opportunities for improvement within the context of a continuous and repeatable process,

- assess progress toward the target state, and

- communicate among internal and external stakeholders about cybersecurity risk.

NIST provides seven steps to establishing a cybersecurity program (NIST, 2014) and the notional information and decision flows of the framework can be applied at the macro-, meso-, and micro-tiers. More specific procurement considerations and guidance for each tier of interoperability follows. Each tier description will include brief security guidance.

MACRO-TIER CONSIDERATIONS AND GUIDANCE

At the macro-tier level, the incentives offered over the past several years by the Affordable Care Act and Meaningful Use have resulted in Health Information Exchanges (HIEs) for information sharing across statewide health systems. Information at this level

is shared mainly through the HL7 Clinical Document Architecture (CDA), a clinical document framework designed to be readable by both humans and computers (Oemig and Snelick, 2016). Given that connectivity exists and is spreading across the country, the discussion here focuses on reported challenges related to usability, quality, and security of the data exchanged.

Usability. One issue affecting usability of data exchanged at the macro-tier level is the sheer volume of information. For example, a very common type of document—a discharge summary—may be on the order of 50 pages. The number of documents, combined with the detail contained in each, can easily overwhelm a provider. Large volumes of data for each patient from each provider creates fragmented snapshots that are challenging for clinicians to absorb, potentially leading to misdiagnoses, unneeded testing, medical errors, and workload fatigue.

Next-generation HIEs may offer enhanced controls and capabilities that substantially reduce unnecessary data volume. Health care organizations should engage with regional and state HIE headquarters to understand requirements that may be levied on their individual systems to support these initiatives. Not all stakeholders require access to all of the patient’s data. Stakeholders (clinicians, payers, researchers, and so on) should define default “views” specifying only the data they require—views that capture relevant data across all “fragments”—and assemble that data into a seamless view of the patient’s record (i.e., a dashboard). The use of well-contrived views may reduce the amount of redundant information in the overall network. Research has been performed on methods for identifying, extracting, and aggregating unique content from multiple clinical documents on the same patient (Dixon et al. 2017). Individual hospitals should advocate further research in this area and monitor developments in commercially available predictive analytic algorithms and population health management tools.

Quality. Challenges with quality at the macro-tier include data accuracy, timeliness, and meaning (semantics). Data accuracy and completeness issues include wrong fields; incorrect use of terminology codes; missing data (empty fields); and invalid, unreadable, or inconsistent entries. The issues with data timeliness result in outdated, incorrect information. Variation in data semantics means different health information systems can use different dictionaries for various medical domains. Translation of services provided into documentation codes can vary among clinicians and among health care organizations.

Automated tools exist to validate the quality of CDA documents. ONC’s C-CDA Scorecard, for example, provides implementers with industry best practice and usage. The Scorecard promotes best practices in C-CDA implementation by assessing key aspects of the structured data found in individual documents, as well as assessments on key areas for improvement. Health care organizations should

push for the maturation and transitioning of these tools from today’s stand-alone “test tools” into background real-time Continuity of Care Document (CCD)quality check tools that can trigger alerts caused by data entry issues and can ensure that interoperability does not degrade system performance.

Finally, patient matching is a challenge that exists at all tiers and is especially important to quality at the macro-tier where records for a single individual may exist at multiple locations, provider organizations, and health systems that have yet to come together to form a comprehensive picture of a patient’s care. Accurate patient-matching approaches is an active area of research, and given the importance of correct patient matching, health care organizations are encouraged to track developments in this area (e.g., the Sequoia Project, 2015; Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT, 2017a) and the subsequent effect on interoperability-related procurement language.

Cybersecurity and privacy. Security and privacy at the macro-tier starts with an identified threat model. In inter-facility information exchanges, there is a greater risk of data aggregation and exposure for a wide variety of nefarious purposes ranging from identity theft, fraud, and public exposure to deliberate life-critical modifications of data between facilities. Key mitigations at the macro-tier include common authentication/authorization between facilities, immutable logs to identify threat actors, and encrypted communications between facilities. Typically, these would be included in requirements for the use of information exchange gateways.

Envisioning the macro-tier of the future. The future of macro-tier interoperability can best be described by analogy: in the cellular communications industry today, regardless of whether one person uses Mobile Service Provider A and another uses Provider B, we expect to be able to communicate via voice and/or data (e.g., text message). In health care today, the situation is such that a hospital using Provider A can talk only to other Provider A hospitals. Organizations such as CommonWell Health Alliance (which is a trade association of health IT vendors that provides technical infrastructure to enhance patient matching, data query and retrieval, and person enrollment) are taking on the interoperability challenges at the macro-tier to support cross-vendor data exchange.

MESO-TIER CONSIDERATIONS AND GUIDANCE

At the meso-tier, individual hospitals or clinics handle data and information associated with the EHR and other medical IT systems such as labs or pharmacies, and from operational and administrative IT systems such as food services or facilities,

and admission/discharge/transfer (ADT). Data at this tier support the operation and administration of activities within the hospital, including clinical activities such as forming and maintaining a picture of the patient’s care and condition over time; moving patients and supplies where they are needed; scheduling resources; and so on.

In the current state, hospitals tend to procure pharmacy, laboratory, and other health information technology (HIT) systems that integrate with their respective EHR. EHR vendors may include these HIT systems as part of their product line, which hospitals might opt to purchase as “bundled” services. Alternatively, hospitals might procure solutions for these HIT systems from other (i.e., non-EHR) vendors and pay additional costs for integrating these systems with the EHR. These custom integrations may involve vendor-to-vendor agreements that must be managed over the long term. Although interoperability between these systems can be achieved, neither of these approaches—bundled HIT or custom integrations—are open architecture solutions, and significant additional resource investments and maintenance will be required over the product’s life cycle. These models of achieving meso-tier interoperability are typically not scalable and hence not sustainable as a long-term solution for the industry.

Requiring health IT vendors to use best-practice data exchange standards, integration profiles, and implementation guides for their products’ interfaces is part of the strategy to achieving more open systems. A complicating factor at the meso-tier is that health IT systems are typically large-scale capital investments that health care organizations retain over many years. Given the lengthy life cycles for these systems and the disparity of types of systems, progress toward open systems must be incremental.

As an example, a hospital procures an upgrade to the laboratory information system (LIS) that includes the ONC Interoperability Standards Advisory (ISA)–recommended standard interface between the LIS and the EHR system. Suppose the hospital’s EHR system is an older design that does not support the ONC Interoperability Standards Authority (ISA)-recommended LIS interface. The hospital could update the EHR system, but the current HIT budget might not support this. Another alternative is the use of an interoperability platform—(i.e., software and host computer systems that translate or transform a data interface from one form to another and facilitate the interconnection of different systems or subsystems). An open architecture interoperability platform, which is a data exchange framework composed of open and standard components and interfaces, is key to achieving the full benefit of interoperability and an open business model.

In this example, open architecture middleware serves as a bridge between the new LIS and legacy EHR, enabling retention of interoperability between the two.

At some point in the future when the EHR system is upgraded to the standard LIS-EHR interface, the open architecture middleware may be deemed unnecessary. Alternatively, the open architecture middleware might be retained to serve as the bridge interface to other systems having noncompatible interfaces within the same tier (e.g., meso-tier), but also across tiers (i.e., macro- or micro-tiers).

In addition to considering the potential benefits of open architecture middleware, health care organizations should monitor the progress of the new Fast Interoperability Healthcare Resources (FHIR) health data exchange standard. FHIR is the newest addition to the HL7 family of standards and includes many components of prior versions. The ONC has recognized the standard as being the “best available” one, and several major EHR system developers are incorporating early FHIR capabilities into their new systems.

FHIR bundles different types of health care information (e.g., administrative, clinical, financial, research, public health, and so on) into units called resources. HIT systems interconnect through a network and request and exchange resources with each other through a simple-to-use, web-based application programming interface (API). In this way, FHIR resources are available to all systems (though not always in real time), and a requesting system receives only the resources they request, making management of health-related data significantly easier and more reliable. Like other health data exchange standards, integration profiles and implementation guides are being developed for FHIR-based interfaces to satisfy various interoperability needs. FHIR development has largely focused on the macro- and meso- interoperability tiers, but use of FHIR at the micro-tier is also being considered (HL7 Wiki, 2017).

Cybersecurity and privacy. Within a facility, privacy is usually assured through physical access controls and traditional user authentication to critical systems. The automated information sharing between systems benefits from these factors. However, integration within a single vendor or between vendors may require a significant security infrastructure to ensure that all organizations sharing information use a common system authentication infrastructure to ensure that threats cannot gain access by disguising themselves as a legitimate organization for the purpose of violating privacy or modifying data within critical systems. Additionally, the increased use of wireless communications for meso-tier interoperability enables the connection of a threat that may be outside the security perimeter of the facility (e.g., in the parking lot). These facility authentication systems are historically difficult to configure and manage in a dynamic health care environment that includes automated department-to-department sharing, so it is important to address these growing complexities as increased meso-tier information sharing is established.

MICRO-TIER CONSIDERATIONS AND GUIDANCE

The micro-tier represents the data exchanged at the point of care or from patients themselves through wearable devices or mobile health applications. These data may be disparate, ranging from verbal communications, medical record entries, device settings, images, and laboratory results to nontraditional data such as genomics information. Moreover, the data may or may not be generated and transmitted electronically. For example, some medical devices do not connect to any other systems, meaning a person must interpret the data from that device and manually enter it into other pertinent systems such as the EHR. The staff doing this interpretation and manual entry becomes a critical—though often inefficient—element in the information pipeline.

Having a clinician in the information pipeline is certainly essential, but in many cases, the individual is simply a conduit by which to transfer data or information. In such cases, reliance on manual transfer of information can undermine patient safety and caregiver productivity (American Hospital Association, 2018; Sinsky et al. 2016; Reves, 2003). Error in manually copied-and-pasted or entered data at the micro-tier is one of the root causes of data quality issues prevalent at the meso- and macro-interoperability tiers.

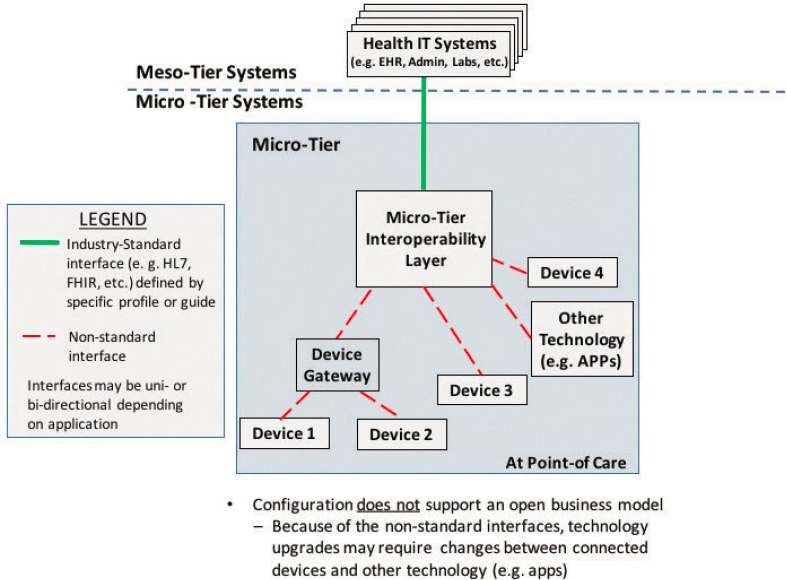

Therefore, a fundamental interoperability need at the micro-tier is the passing of data from medical devices into the enterprise information systems, thereby eliminating unnecessary manual data entry. The health care community has made some progress toward this end, but more progress is needed. Figure A1-4 shows a number of point-of-care devices or device gateways (i.e., device hubs) sending data through a micro-tier interoperability platform that transforms the data into a standardized format for consumption by the EHR. Note that the configuration shown in Figure A1-4 does not fully support an open business model. Ideally, a health care organization would desire the ability to replace or upgrade a particular device with another without affecting the rest of the system. With this ability to purchase in a modular fashion, they can potentially procure from a number of candidate vendors with products that allow plug-andplay. Because of the nonstandard interfaces depicted, which is common in the marketplace today, swapping out a technology with another that has a different interface would likely require major modifications to existing components or a new custom middleware platform. Interoperability platform products with ancillary data services are commercially available, but those relying solely on “middleware” products between proprietary interfaces can be extremely costly.

SOURCE: Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Lab, 2018

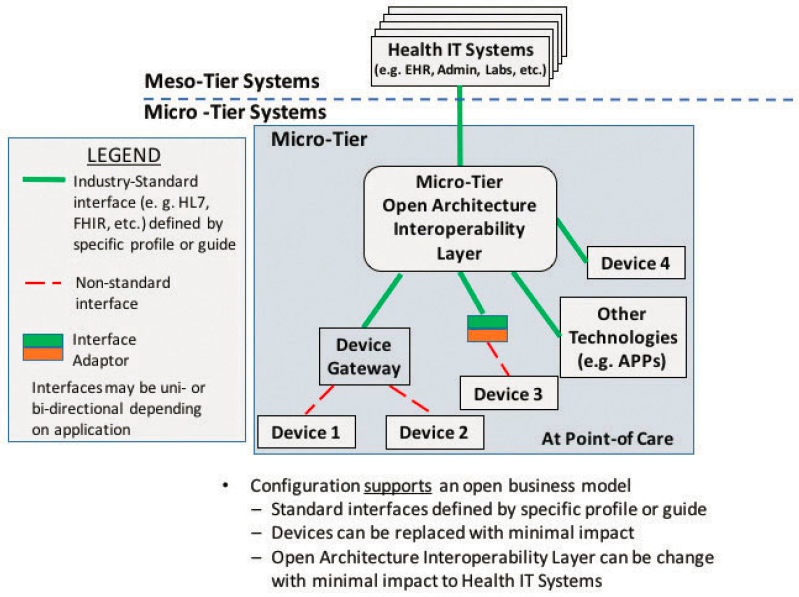

Given the relatively frequent need to upgrade medical devices, it is perhaps at the micro- interoperability tier where health care organizations might benefit most from an open business model. Figure A1-5 shows a fully open configuration where the interfaces between technologies are integrated through an open architecture interoperability platform using accepted standards. With this layer in place in this configuration, migrating any one of the components of the architecture to a new device or application can occur with lower development, integration, and testing expense, an ideal “plug-and-play” state.

As of 2017, the ONC recommends the IHE Device Enterprise Communications (DEC) integration profile for developing the gateway-to-EHR system interface. In procuring the micro-tier interoperability platform, a health care organization would require the vendor to be compliant with the IHE DEC profile. Additionally, the IEEE 11073 family of standards is the most mature work in standardized interfaces for certain classes of medical devices (IEEE Standards Association, 2017). Devices that IEEE 11073 currently addresses include:

- pulse oximeters,

- heart rate monitors,

- blood pressure monitors,

- thermometers,

- glucose meters,

- weight scales, and others.

Unfortunately, health care vendors of these types of devices have typically adopted only selected parts of IEEE 11073, notably the data dictionary (i.e., nomenclature). The parts of IEEE 11073 pertaining to communications transport, protocols, and message syntax, essential for standardizing device interfaces, have been largely unused. IEEE is working on augmenting the current IEEE 11073 family to include more flexible web-based communications methods. In recent years, the FHIR interface standard is being widely adopted for medical devices (HL7 Wiki, 2017).

SOURCE: Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Lab, 2018

Health care organizations should favor device vendors who more fully comply with IEEE 11073 and other enhanced or new standards that follow. Given the relatively frequent need to upgrade medical devices, it is perhaps at the micro-tier interoperability where health care organizations might benefit most from an open business model. To realize this, device vendors need to support standard device interfaces.

Micro-tier interoperability increasingly includes health data that come from the patient portals, mobile health applications, and wearable personal care devices. The Personal Connected Health Alliance provides design guidance built upon the foundation of the IHE DEC integration profile and the IEEE 11073 family of medical device standards. The Personal Connected Health Alliance design guideline is an important resource that health care organizations can draw upon to aid in developing procurement specifications for open and interoperable systems. In addition, for portals, decision support, and other health IT (e.g., apps), the SMART on FHIR platform (Box A1-3) affords a means to capitalize on the growing adoption and maturity of the FHIR specification.

Section 3 of this Technical Supplement contains more details and resources on interface standards that can facilitate more specific procurement languages. In addition, entities such as the IHE, HL7, and the Medical Device Plug and Play (MD PnP) program (Box A1-4) also maintain resources related to integration profiles, sample languages, and clinical use cases for health care provider systems in navigating the marketplace through procurement specifications.

In the long run, however, the concept of a collaborative, open, API-based interoperability platform to allow the micro-tier to move toward a more vendor-neutral marketplace is embraced by many health care stakeholders. One

organization that operates in this space is the Center for Medical Interoperability (CMI, Box A1-5). The CMI’s conceptual framework envisions a future of micro-tier health data exchange where an interoperability platform developed through collaborative research and development interfaces with devices as well as the application layer. If successful, such an API-based platform can enable more efficient procurement of plug-and-play technology, circumventing the frustration and cost challenges associated with closed middleware solutions that are prevalent today.

Interoperability is only a means to an end. Health care organizations should characterize the specific interoperability needs for these technologies, and demonstrate how enhanced connectivity improves patient care and workflow. Health care provider organizations can then leverage the processes outlined in this Technical Supplement to identify data exchange standards, best-practice integration profiles, and implementation guides that specifically target their

interoperability needs for vendors to comply. As of now, some interoperability needs may require the vendor to build a custom interface as a last resort. In this case, the RFP should stipulate that the vendor demonstrate use of open architecture practices highlighted in Section 3 of this Technical Supplement, in particular full documentation and disclosure of the interface design.

Cybersecurity and privacy considerations. At the micro-tier, specific concerns take the form of secured and authenticated communications between individual devices. Within a single vendor, these security features may be enabled and be transparent to the use of the equipment, but when linking devices across vendors, there may be additional concerns that require more extensive configuration and maintenance. Open standards and security-enabled APIs will encourage security controls between devices, but the risk here is that the security controls may be disabled to facilitate rapid integration. Health care organizations are encouraged to review the imperatives, recommendations, and actions described by the Healthcare Industry Cybersecurity Task Force (PHE, 2017) related to medical devices and health IT systems. Some of the recommendations have long been implemented widely, such as requiring strong authentication and staff training on security and privacy protection. Other considerations may require additional governance and processes to secure legacy systems, improve transparency among developers and users, and employ strategic and architectural approaches to reduce physical breach or cyberattack of medical devices and health IT technologies. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) also disseminates guidance on mitigating and managing cybersecurity threads and convenes experts on approaches to safeguarding medical devices and health IT systems.

CONCLUSION

Many health care organizations face constant challenges in adopting new capabilities and improving care when their devices and IT systems do not work together as an integrated system. Health care of tomorrow must develop an enterprise-wide architecture that enables system-wide interoperability to fuel a learning organization, as well as encouraging rapid development and adoption of technology innovations. In the interim, health care organizations must adopt a different approach in procuring technology that prioritizes interoperability with greater specificity. Health care organizations must commit to a requirements-driven approach for purchasing new technology that rewards interoperability, modularity, and openness. For many organizations, this means establishing a governance structure to coordinate and guide various internal efforts in leveraging existing implementation profiles and data standards in their procurement

processes. Health care organizations must also work with standards development organizations, vendors, and other provider organizations to expand best practices and share resources. An industry-wide commitment toward this requirements-driven approach, driven by strategic partnerships among provider systems, patients, technology vendors, federal agencies, and other health IT societies, is the only viable path toward a safer, more efficient, and high-value health care enterprise.

This page intentionally left blank.