A Research Agenda Toward Atmospheric Methane Removal (2024)

Chapter: 4 Atmospheric Methane Removal Technologies

4

Atmospheric Methane Removal Technologies

This Committee has been tasked with developing a research agenda for atmospheric methane removal and, specifically, recommending research that could improve sociotechnical understanding of these technologies. Having established the context in which methane removal is being considered (see Chapters 1 and 2) and the motivations for this consideration (see Chapter 3), in this chapter, the Committee assesses the properties and status of the five atmospheric methane removal technologies considered in this report.

This chapter first assesses the five atmospheric methane removal technologies against a set of criteria developed by the Committee. The results of this assessment are presented as a narrative description of the technologies themselves and the criteria they are being assessed against. These assessments are applied to technologies that are all in early stages of research and/or development and thus carry substantial uncertainty. The technologies in this chapter are assessed individually to illustrate differences between the approaches and their potential applications. With the exception of a description of the social issues connected with life-cycle assessment (LCA) (see Box 4-3), this chapter does not substantially examine social considerations, as the relevant governance, public engagement, and justice elements often apply across technology types and their stages of development (presented and discussed in Chapter 5, along with other considerations that cut across all technologies). The Committee undertook the technology assessment described in this chapter to address its task (see Chapter 1), identify key research needs (see Chapter 6), and inform its ability to make judgments about whether investment in research and development (R&D) for these technologies might be the best use of those funds. (See Chapter 5 subsection Trade-offs in Investments and Resource Use for the Committee’s consideration of this question.)

OVERVIEW OF TECHNOLOGIES

The five atmospheric methane removal technologies considered in this report are methane reactors, methane concentrators, surface treatments, ecosystem uptake enhancement, and atmospheric oxidation enhancement (AOE). The Committee selected these five to capture a comprehensive range of potential technologies with the potential to reach effectiveness at atmospheric concentrations of methane (2 parts per million [ppm]). A visual depiction of these technologies is presented in Figure 4-1, with written descriptions included in the following section.

These technologies can be categorized into “open” and “partially closed” systems. Partially closed systems are defined as those bounded by physical barriers where the reactive species (e.g., catalysts) are retained inside but air and energy are allowed to flow through the system. Open systems are defined as those that lack a physical boundary, where reactive species or other management actions are introduced into the atmosphere or other environmental compartments. Reaction mechanisms relevant to each technology type are summarized in Box 4-1.

Methane Reactors

Methane reactors are purpose-built, physically bounded systems that utilize the active flow of air to capture or convert methane to a different chemical species with lower atmospheric warming potential. Due to the low average concentration of methane in the atmosphere (~2 ppm), large volumes of air must be processed to remove a meaningful amount of methane. Therefore, technologies that actively drive air flow in the reactor through energy input—for example, via fans (C. Wang et al., 2023) or via density-driven flow (e.g., solar chimneys; Huang et al., 2021)—are most often considered. While specific areas with higher methane concentrations are known (e.g., in leaking pipelines or near concentrated livestock operations), concentrations are still typically lower than for other atmospheric greenhouse gas (GHG) removal technologies, such as carbon dioxide removal (CDR) by direct air capture (DAC) (Sanz-Pérez et al., 2016). This fact coupled with the symmetric, small, non-polarizable, non-polar nature of methane makes pre-concentrating methane by trapping it with sorbents very challenging, requiring significant energy input (Eyer et al., 2014). Therefore, reactors and reactive components (e.g., catalysts or radical initiators) that efficiently treat methane at ambient concentrations likely will be required.

Within the methane removal reactor, the air flow must be engineered to efficiently contact reactive components that promote the conversion of methane to species with a lower radiative forcing, such as carbon dioxide (CO2). Achieving this without introducing a substantial pressure drop is important to minimizing capital expense (i.e., avoiding the need for a compressor as distinct from a blower or fan).

Many catalysts and other reactive components considered to date convert methane to CO2 via reaction with atmospheric oxygen (Brenneis et al., 2022), though other reactions may also be considered if they efficiently convert methane to products with lower radiative forcing. The reaction promoters within the reactor may be chemical catalysts,

![Stylized illustrations of the five technologies considered in this report: methane reactors, methane concentrators, surface treatments, ecosystem uptake enhancement, and atmospheric oxidation enhancement. Methane concentrators may enable other atmospheric methane removal technologies (e.g., methane reactors, as depicted here). Atmospheric methane removal is human intervention to accelerate the conversion of methane in the atmosphere to a less radiatively potent form (shown here as carbon dioxide [CO2]) or physically remove methane (CH4) from the atmosphere and store it elsewhere. The term “atmospheric methane removal” is also used when human interventions increase the sink and decrease the net flux from ecosystems to the atmosphere, or make the flux negative](https://www.nationalacademies.org/read/27157/assets/images/img-93-1.jpg)

photo-stimulated radicals, or biocatalysts (see Box 4-1). Among chemical/thermal catalysts, photocatalysts and biocatalysts are most often considered, with the former requiring incident light of a suitable wavelength and the latter requiring appropriate reaction temperatures. Among biocatalysts, reactors incorporating appropriate microorganisms are often considered, such as methanotrophic biotrickling filters (Yoon et al., 2009) that host appropriate methane-consuming microorganisms. For such conversion reactions, the activation of the initial carbon-hydrogen bond is challenging due to a high bond dissociation energy (425.14 kJ/mol) (Wang et al., 2017).

This partially closed technology differs from non-physically bounded systems or systems that rely on passive movement of outdoor air, discussed below.

BOX 4-1

Mechanisms of Reaction

Catalytic reaction: A catalyst is a substance that increases the rate of chemical reaction without the catalyst undergoing a permanent chemical change. This is often achieved by lowering the activation energy barrier in a process that regenerates the catalytic species in its active form.

Non-catalytic thermal reaction: Transformation of methane via a process that relies on some input of heat transfer, most often to overcome an activation barrier.

Photocatalytic reaction: Transformation of methane via a process that relies on some input of photons. Note that these processes may be direct or indirect, where light is absorbed by a reactive molecule that can react directly with methane or light is absorbed by a sensitizing species that activates another chemical entity that undergoes subsequent reaction with methane.

Radical reactions: Transformation of methane via reaction with chemical free radicals. A chemical free radical is an atom, molecule, or ion that contains an unpaired electron in a valence electron shell. Radical reactions are promoted by radical initiators, which are chemical substances that give rise to free radicals through some stimulus, such as light or heat.

Biocatalytic reactions: Transformation of methane via microbes that utilize methane as a source of carbon and/or chemical energy. Note that abiotic biochemical reactions (i.e., using lyophilized or laboratory-grown proteins) are categorized as catalytic reactions in this report, whereas living systems requiring inputs and outputs are categorized as methanotrophic reactions.

Methane Concentrators

Methane concentrators are materials or devices that can separate or enrich methane with some degree of selectivity relative to other atmospheric components. Separation of a dilute species from a fluid mixture is often achieved by dissolution into a liquid or sorption onto a solid phase. This separation process requires selective sorption of the target of interest onto the solid or into the liquid. This is achieved by having favorable interactions with the sorbing media relative to the original carrier fluid. Typically, sorption decreases the system’s entropy (i.e., more ordered, which is disfavored). Therefore, sorption is most often driven by favorable enthalpy (emits heat) to result in a thermodynamically favorable process overall. Consequently, energy must be expended to recover the sorbate of interest from the sorbed state in the liquid or on the solid.

Selective sorption is achieved by exploiting a property of the target molecules and the properties of the sorbing media. Typically, molecules with permanent dipoles or quadrupoles, polarizable electron clouds (i.e., larger molecules), or charged moieties/species can be selectively sorbed using suitable media. In contrast, small symmetric molecules, such as methane, are more difficult to sorb. Methane also lacks acid-base chemistry and a permanent dipole, making it extremely challenging to sorb onto solid surfaces or preferentially partition into common liquid media. These characteristics, coupled with the low abundance of methane in the atmosphere (~2 ppm), make methane concentration significantly more challenging in comparison to more abundant quadrupolar species, like CO2 (~420 ppm atmospheric concentration). Here, the Committee notes that most CO2 separators leverage the acid-base chemistry of CO2, where the acidic CO2 reacts with basic species in the solid or liquid sorption media.

In principle, methane can also be concentrated using membrane separators. Membrane separators separate chemical mixtures by relying on size or diffusivity (molecular sieving) or sorption and diffusion through a membrane. Methane is almost the same size as nitrogen, making molecular sieving of atmospheric methane a challenge. Methane is a weakly sorbing molecule as well, making sorption- and diffusion-driven separations of 2 ppm methane a major challenge. In general, membranes are most efficient in concentrating species that are present in elevated or moderately elevated concentrations.

Broadly speaking, separators and concentrators (largely synonymous) and filters typically rely on leveraging some physicochemical property of a molecule to enrich it in or on a target medium relative to the original carrier fluid (e.g., the air, in this context). Such separations can rely on (1) characteristic freezing or melting points, (2) size-exclusion or other size-based separations, (3) diffusion gradients, (4) ionic interactions, (5) acid-base chemistry, or (6) thermodynamically favorable partitioning processes (i.e., sorption). The Committee believes that because of energy and cost constraints, methane concentrators are unlikely to concentrate methane such that a highly concentrated stream can be produced as a product from dilute atmospheric concentrations. The inclusion of this partially closed technology reflects the Committee’s judgment that methane concentrators could, in principle, remove methane from the air and could be used upstream of methane reactors or for purposes of enhanced mitigation.

Surface Treatments

Surface treatments are the application of a catalyst to a built or other surface that contacts air naturally to convert methane to a different species with lower atmospheric warming potential. Surfaces that contact air naturally can be coated or functionalized with catalytic sites or entities that are capable of converting methane to other less radiatively potent products. As in the case of atmospheric methane removal reactors, these coatings may contain thermal catalysts (Brenneis et al., 2022), photocatalysts (Chen et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2023), or biocatalysts (Majdinasab & Yuan, 2017) that efficiently remove methane from gas streams. The surface treatment category differs from reactors in that the catalysts are not contained in a physically bounded system but rather are coated on a surface that has natural exposure to air in the environment. Advantaged systems are those that give long catalyst lifetimes, maximize the exposed surface area between the surface and the air, feature high fluxes of air past the treated surfaces and/or address mass transfer limitations, and exhibit high efficiencies (i.e., high quantum yields in the case of photocatalysts and low conversion temperatures in the case of thermal catalysts). Note that efforts to maximize the durability of the surface treatment are advantageous as well (including avoidance of fouling, poisoning, or deactivation). Hypothetical examples might include catalytic paints on rooftops, trains, or wind turbine blades, or aerosolized particles to maximize surface area (Randall et al., 2024). Examples of photocatalytic surfaces for removal of other pollutants, such as nitrogen oxides (NOx), are well researched (Tang et al., 2021).

This technology is an open system approach that would require anthropogenic mobilization of engineered or natural materials onto built surfaces, with implications for broader environmental effects, and require monitoring, reporting, and verification (MRV), detailed in sections below and Chapter 5.

Ecosystem Uptake Enhancement

Ecosystem uptake enhancement is an amendment or practice that augments the in situ net uptake of methane by or within primarily managed ecosystems, with potential application to natural ecosystems. Natural ecosystems are highly variable, widely distributed, and often inaccessible, such that technologies aimed at enhancing methane uptake cannot be readily deployed or subjected to MRV. Thus, technologies in this section are targeted to managed ecosystems.

Aerobic and anaerobic methanotrophic microorganisms contribute to the biological methane sink in the biosphere. The diversity and activity of methanotrophic communities depend on ecosystem type, with drier systems (e.g., upland soils) acting as net methane sinks (Voigt et al., 2023) and wetter, warmer systems (e.g., rice paddies) acting as net methane sources. Enhancement of atmospheric methane removal over intrinsic methane production can be accomplished by amending soils that tend to be net methane emitters with biochar (Han et al., 2016; Zhao et al., 2021), organic residues (Ho et al., 2015), sulfate (Gauci et al., 2008), or iron plus humic acids (Miller et al., 2015),

among others. However, some studies have found that biochar must be re-applied after 1–2 years to enhance methane removal from soils (Liu et al., 2019; Nan et al., 2020).

Biochar and organic residue amendments work by altering the activities, but not necessarily the types, of microorganisms present in methane-emitting soils (irrigated, carbon-rich systems, such as rice paddies) (Ho et al., 2015; Zhao et al., 2021). In these situations, the addition of sulfate and iron plus humic acids work by providing alternative electron acceptors to microbial communities to out-compete methanogens and promote methanotrophs. Some aerobic methanotrophs can respire alternative electron acceptors in anoxic soils (Zhao et al., 2023). Thus, soil amendments can both amplify methanotrophic activity and diminish methanogenic activity, although results vary with the type and quality of amendment, the geo- and physicochemical state of the soil (e.g., aeration and carbon content), and the resident microbial community. The observed effects of soil amendments are often transient, requiring re-application to achieve measurable methane consumption over background levels.

Alternatively, in agricultural systems or in degraded soils, management practices could be implemented to enhance soil methane uptake, such as restorative practices to improve overall soil quality (e.g., changes in water-filled pore space, bulk density, pH), or could be changed to include irrigation or tillage (Liu et al., 2021; Meng et al., 2020; B. Wu et al., 2020).

Aside from soil amendments, enhancing or modifying methanotrophic microbial communities occupying the plant phyllosphere—the aboveground plant surface (e.g., leaves)—is another mechanism to accelerate uptake by ecosystems. Genetic signatures of both methanotrophic and methanogenic microorganisms have been identified in the phyllosphere in pine and spruce needles (Putkinen et al., 2021), and methanotrophs have been cultivated from the leaves of several different species of deciduous trees (Iguchi et al., 2012) and herbaceous plants (Yurimoto & Sakai, 2022).

Ecosystem amendment technologies should be considered as providing functions of methanogenesis and methanotrophy but in conjunction with the physicochemical variables of the targeted ecosystems. It is also important to consider that changes in land management practices alone (e.g., tillage style, drainage, clearing, change in plant cover) can alter methane consumption and net methane emission dynamics dramatically (Smith & Conen, 2004). Thus, land management practices should be investigated further as approaches toward enhancing ecosystem-scale atmospheric methane removal (see Chapter 6).

Although aquatic ecosystems can also be strong methane sources (Engram et al., 2020), their potential for atmospheric methane removal was not considered in this report.

Ecosystem uptake enhancement is an open system approach that would require anthropogenic mobilization of engineered or natural materials into the environment—with implications for ecosystem services, biodiversity, and nutrient cycling—and require MRV, detailed in sections below and Chapter 5.

Atmospheric Oxidation Enhancement

AOE accelerates the natural conversion of methane in the atmosphere by augmenting the abundance or lifetime of methane sinks (i.e., chlorine [Cl] atom or hydroxyl radical [OH], responsible for 5–6% and 90% of the natural methane sinks, respectively) (Saunois et al., 2024). The Cl sink is predominantly in the stratosphere (33 [11–43] teragrams [Tg] CH4 yr-1), with a small contribution from the oxidation in the marine boundary layer (6 [1–13] Tg CH4 yr-1) (Saunois et al., 2024); both sinks have large uncertainties (e.g., Allan et al., 2007; Gromov et al., 2018; Portmann et al., 2012). The two primary AOE approaches considered in this report are chlorine-based and hydrogen peroxide–based approaches.

One proposal to enhance the abundance of OH and Cl is to introduce iron salt aerosols into the lower troposphere (Meidan et al., 2024; Ming et al., 2021; Oeste et al., 2017). The concept behind iron salt aerosols is to mimic a natural process that occurs when mineral dust combines with sea spray aerosols in the atmosphere (Gorham et al., 2024; Mikkelsen et al., 2024; van Herpen et al., 2023). Iron can promote the formation of Cl in the presence of sea salt aerosols and sunlight (Wittmer, Bleicher, et al., 2015; Wittmer & Zetzsch, 2017). The addition of iron can, under some conditions, accelerate methane oxidation associated with Cl; however, other conditions may reduce methane oxidation due to decreases in OH (Li et al., 2023; Meidan et al., 2024; Ming et al., 2021; Oeste et al., 2017). Iron can also catalyze the formation of OH reactions in the presence of moisture (i.e., clouds and rain drops), resulting in an additional source of OH beyond daylight hours (Deguillaume et al., 2005; Nakatani et al., 2007). This untested approach would involve releasing iron-based particles—for example, from ships or towers. Another potential approach to generate OH could involve release of hydrogen peroxide via downdraft energy towers and/or artificial ultraviolet (UV) radiation (Tao et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2022). A preliminary study suggests that the requirements for the amount of hydrogen peroxide are so large that this method may not be feasible (Horowitz, 2024). Research on AOE is nascent with few published studies and modeling results available for analysis by the Committee.

This technology is an open system approach that would require anthropogenic mobilization of engineered or natural materials into the atmosphere, raising particular issues for consideration, such as MRV, detailed in sections below and Chapter 5.

TECHNOLOGY ASSESSMENT

The following section presents the Committee’s high-level evaluation of each atmospheric methane removal technology against a set of key criteria to assess its current performance. First, technology assessment criteria are introduced; then, the technologies are assessed in the order in which they were introduced above. Considerations that cut across all technologies are discussed in Chapter 5.

Technology Assessment Criteria

The Committee has assessed the five technologies against the same set of criteria. These criteria were selected by the Committee as meaningful indicators of each technology’s advancement toward a pathway for methane removal at ~2 ppm atmospheric concentrations that could be eventually considered for demonstration and/or deployment. This exercise assessed the current performance of each technology and informed the Committee’s research agenda in Chapter 6. Due to the limited knowledge base for all atmospheric methane removal technologies, quantitative rankings or evaluations of each criterion were not made. Social impacts and public engagement needs are addressed in Chapter 5.

The criteria that each technology was assessed against are as follows.

Technical Efficacy and Feasibility

This criterion considers whether a feasible technical pathway exists for each atmospheric methane removal technology to accelerate the selective removal or the conversion of methane to CO2 in the atmosphere beyond the natural rate. Abernethy and Jackson (2024) have noted that a technology should be net climate-beneficial. That is, “any warming caused by implementing the approach (e.g., by greenhouse gases emitted during electricity generation) must be outweighed by any cooling (primarily due to the methane removed but also from other radiative impacts)” (Abernethy & Jackson, 2024).

Scalability

Scalability describes the potential for an atmospheric methane removal technology to remove methane at a scale where it could be meaningfully considered as part of a portfolio of solutions to address climate change. Scalability may be impacted by a variety of factors depending on the technology: ability to achieve meaningful removal rates at atmospheric concentrations of methane given constraints on energy, land, and resource use; supply and demand for materials; environmental and social risks associated with implementation; and economic viability, among others. Although every amount of methane removed lowers climate risks, Abernethy and Jackson (2024) suggest a benchmark scale of relevance for each approach of 1 million tonnes (Mt) yr-1 of methane by 2050; removing 1 Mt yr-1 for three decades would lessen the methane emissions gap and cut ~0.002°C from a hypothetical scenario in which global warming peaks at 2°C in 2080. For comparison, the transient climate response to cumulative emissions of CO2 is 0.00048 ± 0.0001°C per Gt CO2 (Arora et al., 2020). The comparable methane climate response is 0.00021 ± 0.00004°C per effective Mt CH4 removed, with ongoing methane removal required to maintain an effective cumulative removal (Abernethy et al., 2021).

Requirements to Remove 1 Mt of Methane per Year and Estimate of Maximum Removal Capacity

While methane removal technologies are not ready for climate-relevant deployment, it can be instructive to consider what such a deployment might require, given the current state of knowledge. Here, the Committee presents simple estimates of what it would take to deploy these technologies at the 1 Mt CH4 yr-1 removal scale at current atmospheric methane concentrations, assuming these technologies could be developed. These levelized removal requirements are used to estimate a maximum atmospheric methane removal capacity, albeit with significant assumptions.

For a given quantity of GHG removal, the minimum amount of gas or air that must be processed is inversely proportional to the concentration of the GHG. That is, a more dilute species, like CO2 or methane from the atmosphere, will require a much larger volume of gas to be moved than a higher-concentration species, such as nitrogen gas (N2) in the atmosphere or CO2 or methane from a point source like natural gas combined-cycle flue gas or coal-mine ventilation. The Committee presents a comparison of the minimum volume of gas that must be processed to demonstrate the difference in these applications (see Table 4-1); at these scales, the energy required to move air for atmospheric methane removal can be significant, and approximate preliminary estimates are derived below for closed technologies.

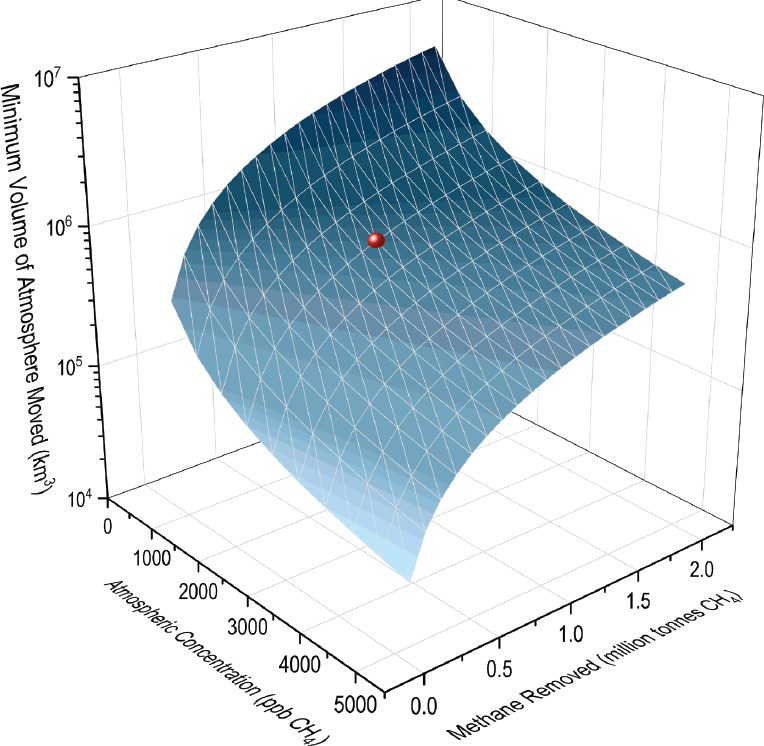

A characterization of the relationship between atmospheric methane concentration, volume of atmosphere moved, and amount of methane removed is presented in Figure 4-2.

As noted previously, current atmospheric methane concentrations have exceeded 1.9 ppm (Lan et al., 2024), with the most recent global methane budget estimating global methane emissions from 2010 to 2019 to be 669 Tg CH4 yr−1 (Saunois et al., 2024). Currently available mitigation measures in the fossil fuel, waste, and agricultural sectors could reduce emissions by as much as 180 Mt yr-1 by 2030 (UNEP & CACC, 2021).

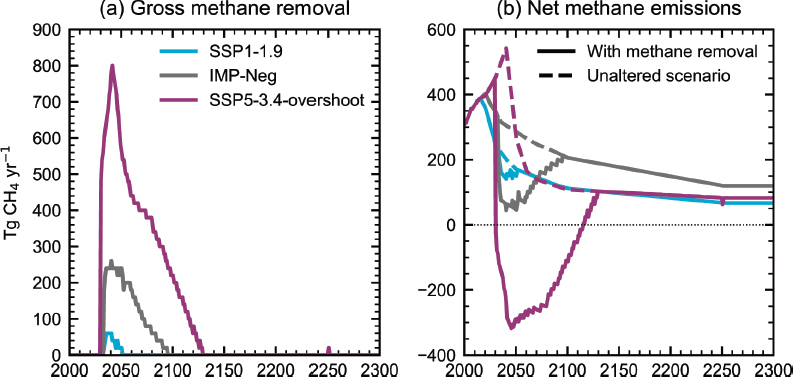

Smith and Mathison (2024) find that the methane removal required to limit peak warming to 1.5°C under Shared Socioeconomic Pathway (SSP) 1-1.9 scenarios (“1.5°C low or no overshoot” scenario in IPCC [2023b]) is 60 Mt yr-1, with up to 800 Mt yr-1 required to reduce peak warming by more than 0.7°C under SSP5-3.4 scenarios that

TABLE 4-1 Committee Calculations of the Minimum Volume of Gas Required to Process 1 Million Tonnes (Mt) of Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Emissions Per Year, Assuming 100 Percent Removal Efficiency

| Application | Minimum Volume of Gas for 1 Mt GHG/Year |

|---|---|

| Natural gas combined-cycle flue gas (4% carbon dioxide [CO2]) | 13 km3 |

| Coal mine ventilation gas (up to 1% methane) | 140 km3 |

| CO2 direct air capture (420 parts per million [ppm]) | 1,300 km3 |

| Atmospheric methane removal (2 ppm) | 700,000 km3 |

SOURCE: Smith and Mathison (2024).

overshoot 2°C mid-century (see Figure 4-3). These findings provide one reference for the order of magnitude of the scale of atmospheric methane removal that could be needed for a climate-relevant impact.

IPCC (2023b) estimates that we will need at least 6 Gt yr-1 of CDR by 2050 to limit warming to 1.5°C. If this were all provided by CO2 DAC, this would mean moving a minimum of approximately 7,800,000 km3 of air per year. A similar volume of atmosphere movement is needed for 10 Mt yr-1 of atmospheric methane removal—the quantity identified by Jackson et al. (2019) for atmospheric methane removal to have a climate-scale impact under the atmospheric “restoration” (to preindustrial concentrations) framework. In comparison, following the example calculation given by Dittmeyer et al. (2019), heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning (HVAC) systems servicing the approximately 4 billion square feet of office buildings in the United States (Brookfield, 2024) moved approximately 50,000 km3 yr-1, assuming a volumetric exchange rate of five times per hour, which demonstrates the large scales required for CDR and/or atmospheric methane removal.

Technology Readiness Level Status

The technology readiness level (TRL) is a common metric for assessing where a technology stands in its maturation, as illustrated and explained below in Figure 4-4.

SOURCES: Iowa Technology Institute (n.d.) and U.S. DoD (2010).

The TRL of atmospheric methane removal technologies is assessed by the Committee in this chapter but has also been assessed independently in Edwards et al. (2024), a commissioned analysis that informed the Committee’s thinking. In addition to TRL, other relevant frameworks include adoption readiness level (assessing technology adoption risk and translating this into a readiness score for adoption) (U.S. DOE, n.d.) and manufacturing readiness level (evaluating manufacturing risk, translated into a score for manufacturing maturity) (OSD Manufacturing Technology Program, 2018).

This section also notes the current working methane concentration observed for technologies with relevant stages of demonstration or deployment.

Assessing an Emerging Technology’s Economic Viability and Technical Feasibility

Technoeconomic assessment (TEA) is a methodology used to evaluate a process or product’s technical feasibility and financial viability. It helps to uncover manufacturing costs and identify market opportunities.

When emerging technologies are still in the early stages of R&D, like atmospheric methane removal, and a large degree of uncertainty in their technical performance remains, TEA should be used to guide research through the various stages of technology development by identifying key variables or hot spots that drive costs. Technological performance uncertainty is reduced as progress is made and a higher TRL is achieved; thus, efforts to more quantitatively (versus qualitatively) estimate the economic potential of the technology and identify business cases can be implemented. A detailed discussion of costs, trade-offs, and resource use considerations for the technologies assessed is presented in Chapter 5.

Atmospheric methane removal technologies are in such early stages of R&D that some elements of traditional LCA approaches (including TEA for cost) are challenging. Particular limitations include a difference between the attributes and upstream requirements of a lab-bench technology and what those may look like for the same technology at scale, as well as a lack of life-cycle inventory data for entirely novel components, materials, or processes (see Chapter 6). Anticipatory, or ex-ante, LCA methods have been a subject of recent focus within the research community—aiming to develop a means for assessing emerging technologies (Bergerson et al., 2020; Cucurachi et al., 2018; Sharp & Miller, 2016; Tsoy et al., 2020).

For climate change–driven technologies, LCA (described in Box 4-2) could be conducted in parallel with TEA to assess both the costs and environmental impacts. The close integration of TEA and LCA enables the joint interpretation of identified key variables or hotspots (areas of the product life cycle with particularly high or meaningful impacts) and the balance of trade-offs among technological, economic, and environmental aspects (Langhorst et al., 2022; Mahmud et al., 2021). As traditionally scoped, LCA may not capture important equity and societal impacts. Details on this gap in LCA and a methodological approach for integrating these considerations are presented in Box 4-3.

Many methane removal technologies did not have sufficient data to enable informed LCAs or TEAs at the time of this report’s writing; thus, the Committee does not undertake formal TEA or LCA of atmospheric methane removal technologies in this

BOX 4-2

The Role of Life-Cycle Assessment

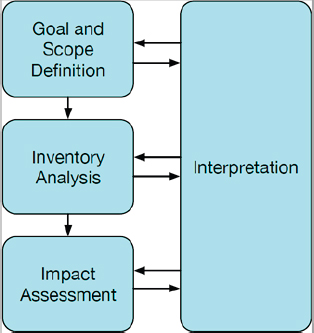

Life-cycle assessment (LCA) is an analytical approach for estimating the full environmental impacts that can be attributed to a particular good or service. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) has codified principles and a framework for LCA (ISO 14040:2006), as well as requirements and guidelines for LCA as an analytical technique (ISO 14044:2006).

LCA can identify factors such as cost, climate forcing, and human health impacts (among others) from raw materials extraction through manufacturing, deployment, and functional lifetime, as well as end-of-life issues for both the technology under consideration and its supply chain systems. It is important to note that the quality of the LCA is subject to the data available and modeling approaches employed.

LCA contains four phases, depicted in Figure 4-2-1. Goal and scope definition outlines the framework for the analysis, inventory analysis catalogs the relevant material and energy flows for the product or service being assessed, and the impact assessment characterizes the inventory data into the impacts being studied (e.g., greenhouse gas emissions per unit of product). Throughout this process, the interpretation phase guides LCA practitioners to ensure that results can be interpreted appropriately (NASEM, 2022b).

Broadly, there are two categories of LCA: attributional and consequential. Attributional LCA holds the system under consideration static, seeking to attribute a portion of observed impacts to a specific process, good, or service; consequential LCA treats the system as dynamic, assessing how changes in part of the system would affect the impacts estimated (Finnveden et al., 2009). Hybrid approaches combine elements of these two LCA approaches. Attention to applying LCA to emerging technologies at early stages of maturity and evaluating prospective outcomes has also increased (Bergerson et al., 2020).

SOURCE: Adapted from ISO 14040:2006 in NASEM (2022b). ©ISO. This material is reproduced from ISO 14040:2006, with permission of the American National Standards Institute (ANSI) on behalf of the International Organization for Standardization. All rights reserved.

LCA impacts can also be characterized in terms of “endpoint” and “midpoint” metrics. Endpoint assessments use indicators that express an aggregate level of damage for an impact—for example, human health impact expressed as overall disease burden, ecosystem impacts in terms of potentially disappeared species, or climate change in terms of overall global warming potential. In contrast, midpoint indicators reflect the potential for damage and are defined somewhere between the emission and the endpoint—for example, toxic equivalency factors for humans and ecosystems and carbon dioxide equivalents for global warming.

BOX 4-3

Connecting Life-Cycle Assessment with Equity and Societal Impacts

Life-cycle assessment (LCA) often has been cast as the key comprehensive means for capturing the full scope of a product or process’s impacts on the world. LCA (described in detail in Box 4-2) has proven to be a thorough analytical approach for accounting for environmental and health impacts across the full life of the product or process and reporting these results in the context of a standardized (“functional”) unit. However, these results often fail to capture key dynamics and impacts from the technology assessed. The environmental or health burdens reported do not capture whether the reported figure disproportionately impacts specific communities. Additionally, the impacts measured often do not account for societal concerns (e.g., use of child or forced labor in a supply chain, health and safety in manufacturing, wages paid and worker bargaining rights, among others).

A movement to capture and calculate impact categories for these outcomes has resulted in the development of social LCA (sLCA). sLCA is a framework for explicitly measuring and analyzing the social impacts of products or systems to guide decision analysis (Bozeman et al., 2022). In practice, sLCA often presents a form of “hotspot” analysis, indicating areas of a supply chain of particular concern or high impacts (Thorstensen & Forsberg, 2016). sLCA is less well developed than social impact analysis and related frameworks, and the ways in which sLCA fits into the broader suite of available frameworks is discussed in Grubert (2024).

While the sLCA approach comes with limitations—many of which stem from data availability, accounting choices, and the role of modeler choices in assessment—sLCA has promise to identify key areas for improving social and equity outcomes. This is particularly applicable to emerging technologies whose design choices are still being made—such as the atmospheric methane removal technologies discussed in this report.

report due to an insufficient knowledge base. The principles behind these approaches have informed and underpinned the Committee’s thinking and judgment toward these technologies. In Chapter 6, the Committee recommends research that would inform and enable future LCA and TEA of atmospheric methane removal technologies.

Energy Input

As with all GHG removal technologies, atmospheric methane removal technologies require energy to create materials, construct systems, and operate processes. These technologies may also require the direct consumption of energy, with indirect GHG emissions created from their creation and supply.

Partially closed systems (methane reactors and methane concentrators) must move air to achieve contact between methane and the reactor/concentrator, which requires continuous energy input for operation, analogous to CO2 DAC technologies. Table 4-1 and the discussion above illustrate the substantial energy required to move air for atmospheric methane removal. The role of the carbon-intensity of electricity sources is discussed in Chapter 5.

In contrast, open systems (surface treatments, ecosystem uptake enhancement, and AOE) rely on passive contact between atmospheric methane and the technology. Specific energy input will vary depending on the technology and the amount of maintenance required—for example, if the intervention is performed once and then the process is operated completely passively versus if the intervention is continuously or intermittently applied.

Durability

In the context of atmospheric methane removal, durability encompasses the resilience, longevity, and ability to continually remove methane from the atmosphere. The durability of a partially closed atmospheric methane removal technology depends on its ability to withstand degradation, damage, and decay in efficiency over time (Pennacchio et al., 2024). For open systems, durability refers to their ability to maintain effectiveness and functionality over time in dynamic and changing environments. To that end, the durability of an atmospheric methane removal technology can be classified broadly into physical and functional durability. Physical durability considers how well the physical components, such as the reactors, blowers, heaters, and other auxiliary equipment, can withstand environmental conditions, operational handling, and usage. Functional durability is related to the ability of a technology to maintain its intended functionality over an extended period. For example, methane reactors and concentrators use catalysts and sorbent/membrane materials that may require periodic replacement due to deactivation, degradation, poisoning, or contamination. Efficient process design, selection of highly selective functional materials, use of corrosion-resistant materials for construction, periodic maintenance and replacement, regular weatherization, and safe operation can improve the durability of a technology. It is important to note that the concept of durability can vary depending on the type of technology and its intended

use. Some technologies are expected to have a shorter deployment cycle, while others are designed for longer-term use.

Co-benefits

Each atmospheric methane removal technology presents potential opportunities for coupling with an additional process or creating an output that is of alternative value. The ability for a co-product derived from atmospheric methane to have commercial viability has not yet been demonstrated at elevated methane concentrations greater than 2 ppm. However, this chapter considers co-benefits as opportunities that strengthen the economic case for a technology’s development (importantly, not social or ecological co-benefits; see Chapter 5).

High value-added products can, in principle, be generated through biological methane conversion into biofuel, bioplastic, methanol, ectoine, protein, and polysaccharides, which can be used as renewable substitutes for a wide range of alternative resources from petroleum, plants, and animals (Guerrero-Cruz et al., 2021; Park & Kim, 2019; Wang et al., 2020). Another example of a co-product is the production of high-quality protein from methane-derived biomass that can be used as a feedstock to reduce the carbon footprint of feed production (El Abbadi et al., 2021; Verbeeck et al., 2021).

In the absence of established markets for removed methane, methane-to-value (e.g., leveraging methanotrophy for producing fertilizer and animal feeds), co-products, or the ability to receive equivalent CDR credits from established CO2 marketplaces would be options to provide marketplace incentives for developing these removal technologies (Rinzler, 2023). However, methane-to-value propositions are only demonstrated for methane concentration greater than 1,000 ppm and have yet to be realized at atmospheric concentrations (see Chapter 3).

Pairing methane removal technologies with an additional process could be a means for scaling these technologies and for potential pathways to commercial viability (though the Committee emphasizes that this is currently at higher-than-atmospheric concentrations of methane; see Chapter 3), whether to reduce costs by being coupled with existing processes or with an additional process to add the economic incentive of co-benefits or the creation of co-products with market value. The ability to couple to another existing process, such as CO2 DAC, may help reduce capital and operating costs by leveraging other infrastructure; however, the existing process will limit the scale of atmospheric methane removal that is possible.

Given the large role that these couplings likely will play, MRV will play an essential role to ensure that climate benefits through reductions in atmospheric methane are truly being attained. These MRV needs are, importantly, not limited to industrial ecosystems and processes but include models of natural methane sinks and flows and modifications thereto (e.g., extension of ecosystem uptake enhancement beyond managed systems, AOE). Given that the approaches draw on areas ranging from ecology to industrial engineering, interdisciplinary knowledge sharing and coordination will be essential for ensuring successful MRV in this area (see Chapter 5) and will be a key feature of a research agenda (see Chapter 6).

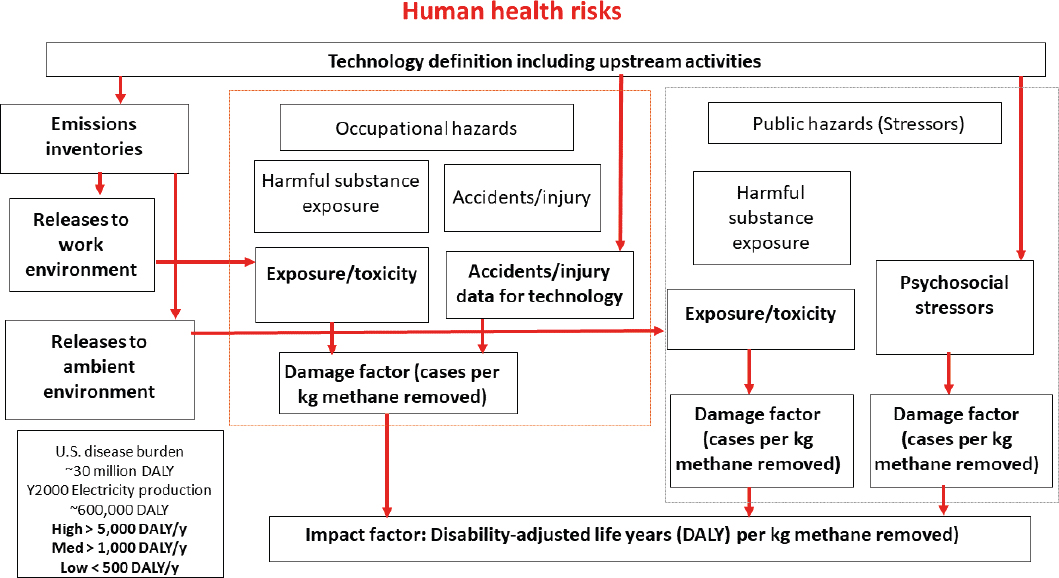

Human Health and Environmental Risks

The characterization of human health risks for atmospheric methane removal technologies can follow standard practice in life-cycle impact assessment (LCIA). LCIA tracks disease and physical injury through the life cycle of a candidate technology with a goal of assessing overall disease burden on a functional unit basis, expressed as disability-adjusted life years (DALY) (Hauschild et al., 2008, 2013). Emissions, exposure, harm, and ultimately disease burden can be expressed per kilogram of methane removed. As illustrated in Figure 4-5, the process begins with a definition of the technology that includes specification of the active technology, as well as components that supply energy and resources, and the major upstream components of the process supply change. Each component has a pollutant emissions inventory per functional unit. The Committee envisions this process as providing a disease burden “endpoint” metric (DALY).

Environmental fate and exposure models combined with toxicity data provide estimates of toxic damages (disease cases per kilogram of methane removed) for both workers and the general public (Huijbregts et al., 2010).

The final DALY outcome can be compared to other DALY estimates. The annual disease burden in the United States from all causes is approximately 30 million DALY (Mokdad et al., 2018). The annual disease burden from electricity production in the year 2000 was estimated at 600,000 DALY (NRC, 2010). The Committee considered any technology with an annual disease burden greater than 5,000 DALY to have a high disease burden and any technology with an annual disease burden below 500 DALY to be low impact.

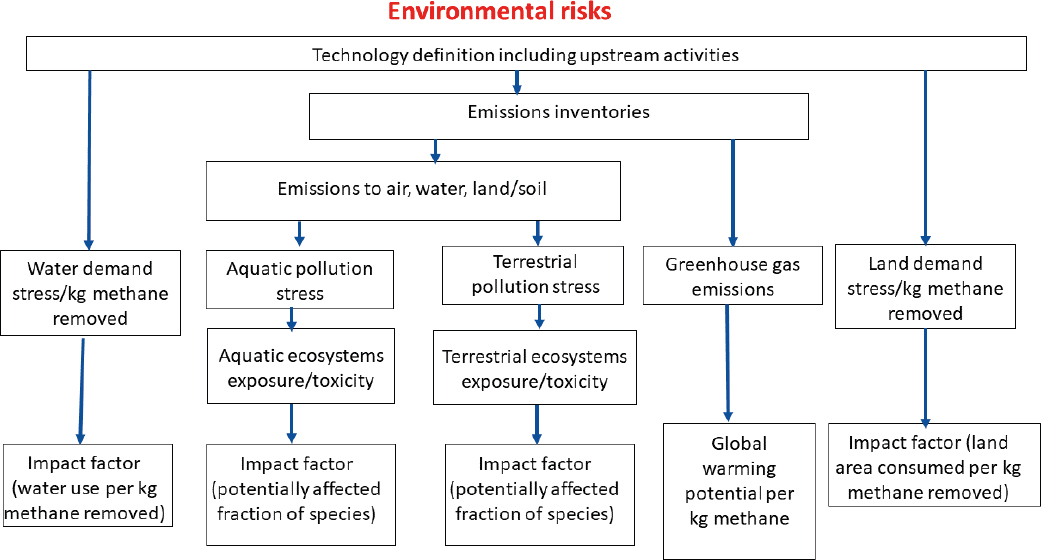

Figure 4-6 illustrates a sample framework for assessing life-cycle environmental risks from atmospheric methane removal technologies. Like the scheme for human health risks, this scheme begins with a process of technology definition that includes not only the atmospheric methane removal process component but also the major upstream (supply chain) and downstream (waste products) components of the technology life cycle (Hauschild et al., 2008, 2013). As was the case for human health impacts, LCIA needs information on the emissions inventories of harmful substances that are associated with the technology components as well as a specification of emissions to water, land, and air that impact terrestrial and/or aquatic species. For ecosystem impacts, the Committee focuses on a “midpoint” metric expressed as a “potentially affected fraction of species.”

Harmful substance emissions are used to assess exposure and toxicity for aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems and to characterize the potential damage to ecosystems in terms of the potentially affected fraction of species per kilogram of methane removed (Huijbregts et al., 2010). For GHGs, the damage metric is CO2 equivalent (CO2e) emissions calculated using a 100- or 20-year global warming potential per kilogram of methane removed. Because environmental stress (and risk) is also linked to water and land use demand, Figure 4-6 includes impacts for total water use and total land use that are indirect measures of potential stress for aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems (Pfister et al., 2009; Taelman et al., 2016). LCIA comprises an important part of the groundwork for formalized assessments of social impacts, as described in Box 4-4.

BOX 4-4

Formal Assessments of Social Impacts

Formal frameworks to assess social impacts for specific projects or policies exist, though their standardized application in practice varies. Historically, social impact analysis frameworks have been aligned with existing frameworks for quantitative financial and environmental assessments (Grubert, 2024). For example, social impact assessment (SIA)—defined as “the process of identifying and managing the social issues of project development [that] includes the effective engagement of affected communities in participatory processes of identification, assessment and management of social impacts” (Vanclay et al., 2015)—emerged in the 1970s alongside environmental impact assessment (EIA). However, while EIA is a well-established field of practice, SIA historically has not been institutionalized to the same degree (Burdge, 2002). Yet, more recently, SIA has moved from being a regulatory tool to something that project managers and even members of civil society have a role in developing. Grubert (2024) details several challenges that have made it difficult to operationalize social impact analysis frameworks, including quantifying and generalizing heterogeneous social impacts, establishing causal connections, defining geographic bounds, and quantifying outcomes that can be good for some and harmful to others.

Legislation like the National Environmental Policy Act already requires some amount of SIA, as do many state laws. In principle, environmental justice assessment is related to SIA but with a focus on things like disproportionate impact and cumulative impacts, which some more general forms of SIA without attention to social difference could miss (Walker, 2010). New legislation in states like New Yorka and New Jerseyb now require the assessment of cumulative impacts on disadvantaged communities as part of permitting decisions.

Grubert (2024) outlines the ways in which some standard social impact analysis frameworks may not be suitable to consider and address environmental justice concerns, particularly the need for procedural justice. Additionally, technologies like carbon dioxide removal or atmospheric methane removal are not simply deployed and have an “impact” on society; society also creates the technologies. In other words, the relationship is two-way, and so from a research standpoint, the questions are about not just how a technology impacts society but also how choices made in society shape a technology in ways that may enable or constrain particular forms of it. That said, SIA may be one useful tool in identifying and addressing social impacts.

__________________

a See https://legislation.nysenate.gov/pdf/bills/2021/S8830.

Methane Reactors

Technical Efficiency and Feasibility

Methane reactors are severely challenged by the low concentration of methane in the air: ~2 ppm today. This extreme level of dilution means that large volumes of air must be processed to remove a meaningful amount of methane, promising substantial upstream process costs for air movement (see Table 4-1 and Figure 4-2).

Methane reactors most often seek to convert methane with oxygen to CO2, though other reactions may also be considered if they efficiently convert methane to products with lower global warming potential. The reactor can deploy a range of methods to impart the desired chemical reactions, including thermocatalysis, photo- or electrocatalysis, biocatalysis, or radical generation. While all of these technologies can convert methane to CO2 on a small scale using higher concentrations of methane (~1,000 ppm and higher) and some commercial devices that use chemical catalysts in methane combustors operating at higher methane concentrations exist, none of these technologies are known to be effective at current atmospheric methane concentrations.

Methanotrophic microorganisms are natural catalysts that can perform many biochemical conversions at ambient temperature and without the need of high energy input compared with industrial processes (Wang et al., 2020), albeit at significantly lower reaction rates. Studies have predicted that cost-effective methane removal by methanotrophs is feasible if air contains 500 ppm or more methane (Cai et al., 2016; Yoon et al., 2009). If elimination capacities could be increased, the deployment of bioreactors could reduce methane entering the atmosphere significantly (He et al., 2023).

Although methanotrophic bacteria have been isolated with the capacity to grow on 2 ppm methane, development of bioreactors to optimize growth of these microbes by, for example, overcoming the mass transfer limitation of methane into liquid has not been adequately explored. Bioreactors have the potential to function at small scales but likely will face difficulties in scaling, with the Committee seeing difficulties in defining scale-up research.

Elucidating the methane concentration at which the various types of methane reactors could become technologically viable (e.g., as a function of reaction efficiency) is an important research question (see Chapter 6).

Scalability

The energy requirement for moving (and heating) air potentially limits the scalability of methane reactors (Abernethy et al., 2023). If the methane reactor technology could be commensally or synergistically coupled with other forced-air systems, the marginal energy requirement could be lowered. However, in this case, the scale of methane removal rate will be tied to the scale of the air handling system. Moreover, the ultralow concentration of methane in the atmosphere suggests that reaction rates will be low and that systems are likely to operate far from 100 percent removal efficiency. Research into reaction rates (including kinetics and mass transport) and the potential

negative impact of competing reactions from other atmospheric compounds is needed for all methane reactor technologies (see Chapter 6).

Requirements to Remove 1 Mt of Methane per Year and Estimate of Maximum Removal Capacity

For atmospheric methane to contact catalysts deployed in methane reactors, air must be moved. The volume flow rate of air (![]() ) that must be moved over a period of 1 year at standard temperature (298 K) and pressure (1 atm) can be calculated based on the mole fraction of methane in the atmosphere:

) that must be moved over a period of 1 year at standard temperature (298 K) and pressure (1 atm) can be calculated based on the mole fraction of methane in the atmosphere:

where MWCH4 is the molecular weight of methane, 16 g mol-1; t is tonnes of methane; xCH4 is the atmospheric mole fraction of methane, approximately 2 ppm; and ηreactor is the removal efficiency of the methane reactor. The minimum volume of air assumes a removal efficiency of 100 percent, giving the previous result of 700,000 km3 of air movement over a period of 1 year; removal efficiency lower than 100 percent would increase the required volume of air required for 1 year of methane removal rate.

The amount of power (wfan) required by fans to move this air can then be calculated based on the pressure drop incurred in the process of contacting the air with the methane reactor. Low pressure drop structures have been proposed for use in CO2 DAC and may be adapted for atmospheric methane removal. Thus, low pressure drop is considered here for the estimate of the power required by fans to move the air through the reactor:

In the equation above, Δ p is the pressure drop of the methane reactor, here assumed to be 500 Pa, and is the ηfan efficiency, assumed to be 0.7 (McQueen et al., 2020). For the minimum air flow rate presented, the assumed pressure drop and fan efficiency would require approximately 16 GW electricity to operate the fans. This underscores the importance of developing low pressure drop structures with efficient contact between the air and the reactive structures of the atmospheric methane removal systems.

Additionally, for some methane reactor technologies, power must be supplied to maintain the atmospheric methane removal reaction. Particularly in the case of thermocatalytic methane reactors, the air may need to be heated to the reaction temperature to

sustain the rate of reaction. The power required to heat the air (wreactor) can be estimated based on the temperature of the reaction:

where ρair is the density of air at standard temperature (298 K) and pressure (1 atm) (1.204 kg m-3), Cp is the specific isobaric heat capacity of air at 298 K (1.006 kJ kg-1 K-1), and ΔT is the difference between the reaction temperature and the ambient air temperature. A reaction that occurs at 300°C (i.e., a temperature difference of approximately ΔT = 280 K = 280oC) would require in excess of 7,500 GW to heat the air. Of course, not all of the air may need to be heated to this temperature, since the thermocatalytic reaction happens at the catalyst surface, and there may be methods of recovering heat from the air such that this heat is not completely lost. Abernethy et al. (2023) calculated that the temperature increase for cost-neutral atmospheric methane removal is approximately 2°C, underscoring the importance of efficient reactions at low temperature. Similarly, Randall et al. (2024) conclude that fan-driven reactors using light-emitting diode illumination and photocatalysts would achieve methane removal costs of <$100/tCO2e only for apparent quantum yields (AQYs) of >10 percent for methane and >1 percent for nitrous oxide (N2O); they also note that achieving AQYs on the order of 1 percent will be “extremely challenging” for dilute gases broadly.

At the recent 28th Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP28) climate summit, countries pledged to triple global renewable energy capacity to 11,000 GW by 2030 (IEA, 2024). Though this capacity is required for global decarbonization, if this energy were put toward atmospheric methane removal instead, given the above energy requirement estimate, this could contribute to approximately 1.5 Mt yr-1 methane removal (compared to tens to hundreds of Mt yr-1 needed for a climate-scale impact), or 6 × 10-4 ppm yr-1, using the conversation developed by Prather et al. (2012). Given that the rate of renewables deployment must accelerate to meet the COP28 goal, significant amounts of additional renewable energy may not be available for industrial removal of either methane or CO2.

If methane reactors were coupled to CO2 DAC to take advantage of the airflow already occurring, only a limited amount of atmospheric methane removal through methane reactors would be likely. The International Energy Agency and other groups estimate that approximately 1 Gt yr-1 CO2 DAC will be needed in 2050, alongside other CDR technologies (IEA, 2022; Jones et al., 2023). Assuming 70 percent capture efficiency for the CO2 DAC process and 100 percent methane removal efficiency, this amount of CO2 DAC would result in a maximum of 2.5 Mt yr-1 methane removal, or 0.001 ppm yr-1. Importantly, these removal potentials are not true estimates of the maximum removal capacity of methane reactors and will be constrained by a range of sociotechnical factors.

Technology Readiness Level Status

Gas-phase methane combustors for dilute (<1,000 ppm) methane reactors are still under development, at approximately TRL 4. Existing combustors, typically operating at temperatures of 300–400°C or higher, are commercially available and widely deployed for elevated concentrations of methane (~1,000 ppm and higher), at TRL 7–9 (Abernethy et al., 2023; Khabiri et al., 2022; La et al., 2018; Stolaroff et al., 2012; U.S. EPA, 2015).

These systems primarily use thermal catalysts, though photocatalysts are well studied and effective (Liu et al., 2023) but less commercially deployed. Enclosed reactors deploying electrocatalysts, photocatalysts, or radical generating compounds are also at TRL 4, though fewer commercial-scale technologies are using these methods at higher methane concentrations. A laboratory prototype of a novel method based on using chlorine atoms in the gas phase achieved 58 percent removal efficiency with an AQY ranging from 0.48 to 0.56 percent. This suggests that a methane eradication photochemical system might viably remove low-concentration methane from waste air, depending on cost and climate constraints (Krogsbøll et al., 2023). Methane reactors can also deploy microorganisms and their associated biocatalytic pathways. Methanotroph microorganism consortia remove methane at concentrations of 1,000 ppm and greater (TRL 6–8), with additional work needed to enable the technology to operate at atmospheric methane levels (TRL 4).

Energy Input

In all types of methane reactors, air must be moved through the reactor to contact the chemical or biological catalysts with methane, resulting in high energy requirements. Because the atmospheric concentration of methane is 200 times less than that of CO2, any methane reactor for atmospheric methane removal is expected to require substantial work input to contact the same number of molecules, thus increasing the energy required for air movement. At atmospheric concentrations, the minimum work of separation is 60 percent higher for methane than for CO2, meaning that the minimum energy per mole removed for a methane removal system is 60 percent higher than for a CDR system; however, because of the higher radiative forcing of methane, removing 1 mole from the atmosphere has a greater short-term climate impact than removing 1 mole of CO2 (Jackson et al., 2021). Development of ultralow pressure drop contactors is therefore necessary to minimize this component of the energy input. Even with only a 500 Pa (0.005 bar) pressure drop, the Committee’s preliminary estimate suggests that it would require approximately 11 GW of electricity just to overcome the pressure drop of the system that removes 1 Mt CH4 yr-1. Additional energy may be needed for heating, converting, and/or removing the methane from the system.

Even though methane oxidation is exothermic, additional thermal or electrical energy input may be required to activate and sustain the reaction, given the very low concentration of methane in the atmosphere. Abernethy et al. (2023) estimate that for thermal-based methane reactors, the temperature increase allowable for cost-neutral

atmospheric methane removal is only approximately 2°C, given current projections for the cost and carbon intensity of industrial heat. In contrast, state-of-the-art catalysts are typically operated at above 300°C (Brenneis et al., 2022). Innovations in lower pressure drop structured reactors and heat integration and recovery from these systems may help drive the energy input down. Development of processes that are commensal or synergistic with other forced-air systems would also help to reduce the required energy input. For example, the specific energy input for moving air for atmospheric methane removal could be reduced if the technology is coupled with another process, such as DAC or building HVAC systems to convert methane while performing their primary function. This concept has been demonstrated for an elevated concentration (300 ppm) methane-in-air gas stream, highlighting the challenges in catalyst and materials design (Sirigina et al., 2023).

Durability

The durability of methane reactors depends on materials selection, design considerations, operability domains and control, environmental conditions, maintenance and monitoring practices, and safety protocols. The modes of operation (e.g., batch vs. continuous, steady state vs. periodic, slow vs. rapid cycling) can affect the functional durability of methane reactors. If the reactor is constructed using corrosion-resistant and high-quality materials, it is likely to have a higher physical durability. The choice of materials can affect the reactor’s ability to withstand variable humidity, air temperature, and reaction conditions. The chemicals or agents used in these systems need to be stable over time to ensure continued effectiveness. For example, if a biological catalyst is employed, its stability against environmental conditions is crucial for system durability. A robust and optimized design that considers factors such as temperature control, pressure regulation, and ease of maintenance can also contribute to higher durability overall.

Co-benefits

Identifying and leveraging an atmospheric methane removal technology’s synergies with other processes and/or its capacity to create added value through the production of co-benefits could increase the viability of the technology. However, a key issue for atmospheric methane removal is that recovery and use of methane at low concentrations is more difficult than recovery and use of methane at high concentrations.

Most methane reactors accelerate the conversion of methane to CO2. However, conversion of methane into methanol, acetate (from co-reaction with CO2), or alkanes (from co-reaction with other substrates) could expand the product portfolio for downstream processing of carbon skeletons into higher-order products of value (e.g., fuels, platform chemicals, polymers). However, the Committee emphasizes that at atmospheric concentrations, efficient conversion and recovery of co-products presents a substantial challenge.

Photocatalysts can also remove N2O, odor-causing chemicals, volatile organic compounds (VOCs), and hydrogen sulfide to varying degrees. As an example of a miti-

gation effort that could inform the development of removal technologies, photocatalytic reactors in animal-rearing facilities such as dairy barns could have the co-benefit of methane reductions in addition to removing nuisance odor and other hazardous emissions (Koziel, 2023).

Bioreactors with methanotrophic bacteria also have the potential to convert methane streams into value-added products—including single-cell protein, fertilizer, bio-polymers, methanol, and other biologically derived metabolites—but face the same constraints of efficient conversion and recovery as dilute methane streams. Bioreactors may potentially reduce odors, hydrogen sulfide, ammonia, and VOC in biofiltration systems (Devinny et al., 1998; Iranpour et al., 2005; Koziel, 2023).

Human Health and Environmental Risks

Methane reactors use heat, light, or methanotrophs to oxidize methane within a partially closed engineered system. The Committee has sought to assess the potential occupational and public health impacts resulting from emissions inventories of any harmful substances that may be produced in the life cycles of methane reactors, following the schema illustrated in Figures 4-5 and 4-6. Also relevant are occupational injuries and nonchemical stressors for communities adjacent to the reactors. As described above, energy is expected be a significant input, and depending on the source of the energy, there are externalities that include emissions, land use, and water demands as well as impacts associated with maintaining energy production and transmission infrastructure (Edwards et al., 2024). In addition, fabrication, transportation, and disposal of spent catalysts can involve exposures to toxic metals and other harmful substances. Semi-oxidized methane products such as formaldehyde reacting with NOx can create ground-level ozone and smog, with uncertain effects on other climate factors (Edwards et al., 2024). The potential magnitude of these impacts is currently unknown and should be considered in evaluating the external costs of deployment of these technologies. No data about occupational exposures are available for those building and operating methane removal reactors, but existing data from industry may provide valuable insights for this application.

The Committee estimates that most health impacts for the life cycles of methane reactors will be low to medium, assuming that the scale of most reactor operations will be initially limited to areas with higher methane concentrations. Among the endpoints with potential to have “low” impact are occupational injuries, public exposures to catalysts and methane-catalyzed by-products, health impacts from added energy production infrastructure, and air pollution from reactor operation and component manufacture. Endpoints that have the potential for “medium” impact are occupational hazards from some catalysts and catalysts’ by-products, public exposure to noise from fans in forced-air systems, and psychosocial stress from land use disruptions (depending on the scale of the operations).

The Committee expects the initial scale of deployment for methane reactors to limit most environmental impacts to “low” with some exceptions. The environmental impacts that are ranked low are harmful substance emissions to water and land/soil,

water demand stress, GHG emissions from added energy needs (assuming renewable energy sources), and GHG emissions from infrastructure manufacturing. When renewable energy is not fully available for producing energy to run reactor fans, this impact could be “medium.”

Methane Concentrators

Technical Efficiency and Feasibility

A key challenge for all proposed atmospheric methane removal technologies is the dilute concentration of methane in the air. Methane is a small, symmetric molecule that lacks acid-base chemistry and a permanent dipole. As a result, methane is extremely challenging to sorb onto solid surfaces or preferentially partition into common liquid media. When coupled with the extreme dilution noted above, this property of methane makes selective separation of methane from the air via sorption extremely challenging.

However, exploiting sorption selectivity is not the only physical property that one may target. Broadly, fluid separation devices typically rely on leveraging some physicochemical property of a molecule to enrich it in or on a target medium relative to the original carrier fluid (e.g., the air, in this context). Such separations can rely on (1) characteristic freezing or melting points, (2) size-exclusion or other size-based separations, (3) diffusion gradients, (4) ionic interactions, (5) acid-base chemistry, or (6) thermodynamically favorable partitioning processes (i.e., sorption), as discussed above. In the case of separating methane from other atmospheric components, the energetic requirements of (1) are prohibitive due to methane’s low concentration. For (2) and (3), the nearly identical kinetic diameters (a proxy for molecular size relevant to these separations) of methane and N2, the most abundant component in air, make these separation modalities extremely challenging. Approaches (4) and (5) are precluded because methane lacks ionic character and acid-base chemistry. Finally, as noted above, (6) is extremely challenging due to the small, non-polarizable nature of methane that ultimately limits the degree of favorable enthalpic interactions it can have with any surface or solvent. Thus, the extreme dilution of atmospheric methane and the physicochemical properties of methane mean that no efficient methane concentrators currently exist for atmospheric development and/or deployment.

Scalability

No selective sorbents or membrane materials have been identified for methane concentration from the atmosphere, substantially limiting scalability. If a suitable material were to be identified, the energy requirement for moving huge amounts of air would also limit the scalability of methane concentrators. However, if these challenges could be overcome, methane concentrators would benefit any subsequent technology, potentially enabling methane reactors that could operate using the concentrated methane. For example, if methane concentrators could create a gas stream containing on the order of hundreds of parts per million of methane, then existing catalysts could be

economically deployed in a downstream methane reactor to cost-efficiently remove that methane (Abernethy et al., 2023; Brenneis et al., 2022). In this case, the scale of the methane concentrator will be linked to the scale of an associated methane reactor or other methane removal technology.

Requirements to Remove 1 Mt of Methane per Year and Estimate of Maximum Removal Capacity

For adsorbents, similar arguments around minimum air movement and fan power can be made as for methane reactors, as adsorbents require similar types of contact between the air and the active site of the adsorbent. Additional energy input will be needed to heat the adsorbent and release the methane, though it is expected that due to the physiochemical nature of methane, the binding energy of methane will be weak for all adsorbents; hence, the temperature difference required to regenerate the adsorbent would be minimal.

For selective membranes, creating sub-atmospheric pressure on the downstream side of the membrane may be one way to create the driving force for separation. The fraction of gas that passes through the membrane is called the permeate, whereas the gas that does not pass through is called the retentate. The power required for separation via vacuum pumping, wvaccum, can be estimated as follows:

where γ is the adiabatic expansion coefficient for air (1.306, unitless), R is the specific gas constant (8.314 J mol-1 K-1) for air, T is the temperature (K), ypermeate is the concentration of methane in the permeate, and Ppermeate is the pressure of the permeate (Castel et al., 2021). Assuming a CH4/N2 selectivity of 10 (Smith, 2023), the power required to create a vacuum producing a 0.002 percent CH4 flow of gas (20 ppm) at a rate of 1 Mt CH4 yr-1 is 750 GW. In addition, multiple stages might be needed to concentrate methane to the point at which another technology could use it.

It is feasible that some of the renewable energy required for decarbonization could go toward methane concentrator technologies if they enabled another technology. For the 1 Mt CH4 yr-1 case detailed above, this would require a 7 percent increase over the COP28 2030 renewable energy capacity goal (IEA, 2024). As methane concentrators do not themselves perform atmospheric methane removal and are reliant on another technology to perform the removal, the maximum removal capacity cannot be estimated.

Technology Readiness Level Status

All atmospheric methane removal technologies are challenged by the dilute concentration of methane in the air. To this end, effective methane concentrators would aid many atmospheric methane removal technologies. However, the physicochemical properties of methane make it very challenging to separate methane in air. While effective methods for methane separation from concentrated gas streams are deployed on a commercial scale and are even possible at modest levels of dilution (Bae et al., 2014), at ultra-dilute concentrations found in the atmosphere (~2 ppm), no known technology efficiently concentrates methane. Thus, methane concentrators are TRL 1. However, the Committee acknowledges that previous efforts and research in this area may have been limited because no need to concentrate atmospheric methane existed.

Energy Input

Similar to methane reactors, air must be moved through a concentrator to achieve contact between methane and the sorbent or membrane. The theoretical minimum work for separating a stream of air with 2 ppm methane into a concentrated gas stream with 1 percent methane and achieving concentration on only 1 percent of the input methane is only about 20 kJ mol-1 methane. Jackson et al. (2021) present several other cases for theoretical minimum work for methane concentration, with similar energy values. However, as demonstrated for DAC, actual processes likely will require significantly more energy than the theoretical minimum (House et al., 2011).

Given the very low atmospheric concentration of methane, any methane concentrator is expected to require significantly large work input to contact the same number of molecules, thus increasing the amount of energy required for air movement. Inefficiencies may result from the need to compress the incoming air for use with size-selective membranes or from the release of methane from a novel selective sorbent.

Durability

The Committee determines that the durability of methane concentrators is comparable to that of methane reactors. Additional detail on this assessment can be found earlier in this chapter in the durability discussion for methane reactors.

Co-benefits

Although substantially concentrating methane from the dilute atmospheric concentration of 2 ppm is not currently feasible by selective sorption, concentration of methane could enable use of other technologies, such as methane reactors that operate more efficiently at higher methane concentration. Development of such materials should also consider whether they can separate other target gases from dilute streams such as other GHGs (CO2 or N2O), VOCs, sulfur gases, and noxious odorants. However, as methane-sorbing materials are as-of-yet undeveloped, this is an open and highly challenging area of research.

Human Health and Environmental Risks

Because methane concentrators have only been used at relatively high concentrations, energy efficiency at lower (ambient) concentrations is currently unknown, limiting options to assess impacts. The two likely categories of health and environmental impacts from concentrators are (1) those associated with energy supply for energy-intensive processes; and (2) those associated with supply chains for the pre-concentrator equipment, which will depend on specific materials, labor practices, and other characteristics (Grubert, 2024). Understanding life-cycle energy, water, and materials demands as well as the potential for life-cycle air emissions, water releases, and solid waste generation will be important. A final question is whether the projects impose psychosocial stress from smell, noise, lights, traffic, land use, etc.

In considering human health–risk impacts for concentrating technologies, the Committee expects that impacts from air, water, and waste stream emissions will be relatively “low” and that “medium” impacts could arise from uncertain occupational risks and the social/psychological stress associated with siting new infrastructure.

Surface Treatments

Technical Efficiency and Feasibility

Open systems that directly interact with the environment can utilize existing air movement to contact reactive surfaces with air containing methane, negating the upstream process costs discussed previously. These technologies, like methane reactors, still must introduce energy into the system to accelerate the chemical conversion of methane. Chemo-, bio-, or photocatalysts could all be deployed as surface treatments in open systems. Surfaces with significant sun and wind exposure are among the favored structures on which photocatalysts might be deployed. For example, natural or synthetic leaf surfaces could be explored for biological methane conversion as sunlight and available surface area would offset energy and materials costs. Application of surface treatments to aerosol particles to maximize surface area has also been proposed (Randall et al., 2024). While these technologies benefit from low upstream costs, they are challenged by exposure to the open environment (durability, safety, fouling, etc.) and more limited control of energy inputs. Like all cases discussed here, the extreme dilution of methane in air is the single biggest challenge. An additional challenge is the large surface area needed to contact and react with substantial amounts of methane.

Scalability

The scalability of surface treatments is limited by available surface area for coating and the effectiveness of the catalyst applied. As with methane reactors, research into reaction rates and AQYs for photocatalysts at relevant atmospheric concentrations is needed to determine potential removal rates (see Chapter 6). Randall et al. (2024) analyzed a system in which photocatalytic paint covers a rooftop. As wind blows over the

rooftop, GHG molecules convect to a photocatalyst and react under sunlight. Systems targeting atmospheric methane and N2O were modeled to approach removal costs of ~$300/tCO2e at high quantum yields (>1% for CH4 and >0.1% for N2O), well above a $100/tCO2e target common for CDR. Competition with other uses of the surfaces (e.g., rooftop garden/green spaces, rooftop solar installations) may also limit the scalability.

Requirements to Remove 1 Mt of Methane per Year and Estimate of Maximum Removal Capacity