A Research Agenda Toward Atmospheric Methane Removal (2024)

Chapter: 5 Crosscutting Considerations for Research and Development of Atmospheric Methane Removal Technologies

5

Crosscutting Considerations for Research and Development of Atmospheric Methane Removal Technologies

Chapter 4 evaluated individual atmospheric methane removal technologies against a set of criteria to assess the technical potential and challenges of each technology. This chapter examines issues that cut across all technologies—particularly those that inform the potential economic and social viability of atmospheric methane removal—and that required consideration as part of the Committee’s development of a research agenda (see Chapter 6). The following sections of this chapter address governance, public engagement, public perspectives, and environmental justice; other social considerations; the relevant policy landscape; costs, trade-offs, and resource use of atmospheric methane removal technologies; and the potential physical consequences of atmospheric methane removal technologies.

GOVERNANCE, PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT, PUBLIC PERSPECTIVES, AND ENVIRONMENTAL JUSTICE

The Committee considered atmospheric methane removal as fundamentally a sociotechnical problem. The technical aspects discussed in Chapter 4 inevitably must interact with human systems. Better prediction of these interactions will inform what is ultimately a social decision to invest in research, development, and/or deployment of atmospheric methane removal. This section considers potential governance mechanisms, including public engagement needs; the importance of studying public perspectives; and implications of atmospheric methane removal for environmental justice, including climate justice. These concepts and issues are interconnected; for example, different types of public engagement in research can support just processes and outcomes, and understanding of public perspectives can influence approaches to governance. While the nascent state of atmospheric methane removal research limits the conclusions that can be drawn across these areas, a breadth of established literature

and experience can be drawn upon to provide the foundation for the research needs across governance, public engagement, public perspectives, and environmental justice that are identified in Chapter 6.

Governance

Governance refers to the structures and processes that are designed to organize and guide behavior on issues of public interest. Governance can be public and mandatory (e.g., law and policy) or private and voluntary (e.g., developed by nongovernmental organizations [NGOs], philanthropists, or scientific associations), and can span local (e.g., city councils) to global (e.g., United Nations) scales. Governance of emerging technologies can influence relevant decisions about research and/or deployment. Importantly, governance can be either constraining or enabling. Governance that is constraining can, for example, restrict research practices or deployments that are potentially unsafe or too risky, or that disproportionately benefit some groups over others. Governance that is enabling can, for example, build public trust and create pathways for better decision making. Early research governance can also help to ameliorate the distortionary effects of unconstrained for-profit technological development (Grubert & Talati, 2024). Notably, research governance can ensure that emerging technology research is responsible, inclusive, and safe (DSG, 2023a).

Governance for research and/or deployment includes, but is much broader than, formal regulation. Whereas regulation is generally limited to laws and policies imposed by governments or international organizations, governance also includes informal mechanisms that may be developed by governments or nongovernmental actors (e.g., NGOs, scientists, civil society). These informal mechanisms include voluntary guidelines, codes of best practice, social norms, monitoring practices, impact assessment, capacity building, and other means for enhancing transparency and participation (Chhetri et al., 2018; DSG, 2023b). As highlighted by the Academic Working Group on International Governance of Climate Engineering,1 examples of nonregulatory governance for emerging technologies could include nonbinding resolutions by intergovernmental organizations (e.g., the United Nations); voluntary codes of conduct for researchers; rules and requirements imposed by funders, universities, or professional associations; and memoranda of understandings between NGOs, governments, or international organizations, among others (Chhetri et al., 2018).

The burgeoning literature on research governance of carbon dioxide removal (CDR) and other climate interventions such as solar geoengineering offers some lessons relevant to the development of research governance for atmospheric methane removal, in particular open system technologies. However, governance lessons will depend on the specific technology, and further investigation is needed to assess which technologies

___________________

1 The Academic Working Group on International Governance of Climate Engineering (https://ceassessment.org/academic-working-group/) is a forum for climate engineering assessment that consists of academics from around the world and was formed to bring together different perspectives on international governance of solar radiation modification.

might be governed together versus require technology-specific frameworks. As with other climate intervention technologies, Grubert (2024) notes that atmospheric methane removal may pose research governance challenges due to the differences in scale, function, impacts, and social considerations among the different technology approaches.

For the foreseeable future—while atmospheric methane removal remains in early, speculative stages—governance of atmospheric methane removal might best be characterized as anticipatory because, like solar geoengineering, “the very contours of the ‘object of governance’ remain uncertain and largely even unknowable” (Gupta et al., 2020). The specific goals of any research and/or deployment governance mechanism would therefore depend on unfolding risk assessments of different climate futures and on the broad aims or rationales of the governance, ranging from restricting atmospheric methane removal, to being vigilant against atmospheric methane removal, to overseeing atmospheric methane removal, to enabling atmospheric methane removal (Gupta et al., 2020). Before any deployment-scale atmospheric methane removal occurs, an opportunity exists for extensive, inclusive, and deep public engagement from the earliest stages of research and development (R&D).

Conclusion 5.1: Governance proposals for analog technologies are plentiful and could inform the development of research governance structures for atmospheric methane removal technologies, particularly open system technologies. Although empirical testing of proposed structures is only beginning, their design is based on governance theory. This theory has limitations but has provided a foundation for governance design for decades.

Public Engagement

Public engagement is itself a governance mechanism. Many reasons exist for engaging the public, including ensuring that core principles of environmental justice are met (Scott-Buechler et al., 2024) and following rights-based principles of environmental law (e.g., Rio Declaration, Principle 10).2 Engaging with those who are impacted by research (i.e., local communities and other publics) is also critical for enhancing the ethical, scientific, and governance/policy outcomes of research (e.g., Gambelli et al., 2023; Grubert, 2023; Helbig et al., 2015; Karris et al., 2020; Pidgeon et al., 2014). This is especially true for publicly funded research for which research dollars should produce societal impacts that align with values of the polity (Hollmann et al., 2022). Widespread support indicates that early engagement in research is important (Lavery, 2018; Ulibarri, 2015). As highlighted in the paper by Grubert (2024), early engagement that focuses on

major uncertainties, social and ethical issues, and core governance considerations—e.g., why an intervention is needed, who owns it, who is responsible in the event of a failure, and what the distributional impacts might be—is valuable prior to research or

___________________

2 1992 Rio Declaration on Environment and Development, see https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/A_CONF.151_26_Vol.I_Declaration.pdf.

deployment decisions in part because of opportunities to adjust and adapt plans before they are carried out (Thomas et al., 2017).

Research further suggests that early deliberative engagements can mitigate social impacts, which may arise even prior to a proposed project taking place (see Grubert, 2024).

The principle of public participation suggests that those who may be impacted by decision making should have opportunities for involvement in the decision-making process. Participation is both a tenant of environmental justice (see later section) and a norm that is deeply embedded in U.S. law and policymaking, especially surrounding environmental issues (Jinnah & Lindsay, 2016). Public involvement in decision making surrounding controversial and/or high-impact projects, such as research and/or deployment of some emerging climate response technologies as well as clean energy technologies, is crucial for both quality and legitimacy of decision-making outcomes. Importantly, in part due to the highly technical nature of these technologies and how they might fit into a broader climate response portfolio, publics and other interested parties (e.g., scientists and policymakers) need sufficient decision-relevant information to engage effectively. This may require capacity-building efforts, such as those that NGOs in the solar geoengineering space are already undertaking (e.g., The Degrees Initiative3 and the Alliance for Just Deliberation on Solar Geoengineering4).

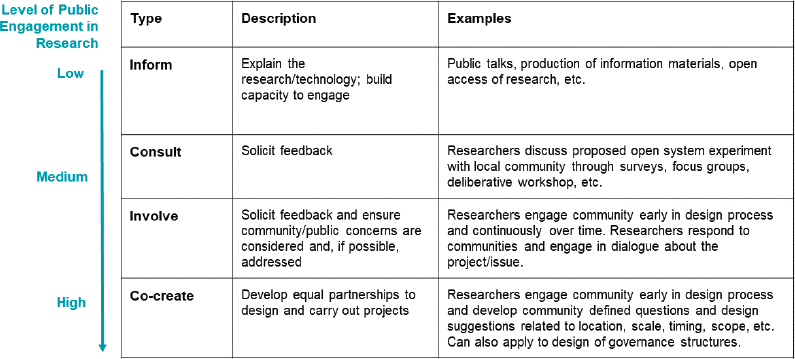

Several general models and guidelines are available for policymakers and researchers to follow in thinking about options for developing engagement strategies (e.g., Bammer, 2021; IAP2, 2018; Newfoundland/Labrador Office of Public Engagement, 2023; OECD, 2015). Although some variation exists across these models, engagement strategies generally range from low to high levels of engagement. Lower levels of engagement—for example, researchers giving public talks or disseminating information through community groups to inform communities—are relatively less time- and resource-intensive and involve less iterative communication between researchers and communities. Higher levels of engagement are more iterative, time-consuming, and resource-intensive. These efforts involve researchers and community members co-designing and/or co-creating research, and/or involve efforts wherein decision-making authority and influence over the research process is transferred to publics and/or communities themselves. Figure 5-1 outlines the different broad “buckets” of engagement strategies that researchers might consider.

In addition to these general models, the Committee draws on insight from specific public engagement examples for solar geoengineering and CDR research to inform its conclusions about public engagement surrounding atmospheric methane removal research. Solar geoengineering research, for example, demonstrates how engagement design will vary across different stages, types, or domains. An effective effort to engage input from relevant parties on a proposed atmospheric research experiment—such as through a deliberative process—will differ greatly from an effective effort to build civil

___________________

SOURCES: Adapted from Bammer (2021) and IAP2 (2018).

society discourse about solar geoengineering research and its governance—such as through broad engagement with accessibility and scalability as goals. Experience from solar geoengineering suggests that attempts to move research and governance forward have been stymied by a lack of attention to engagement and/or low levels of understanding about the technologies and their potential impacts (Jinnah & Nicholson, 2019).

Analysis of recent case studies suggests that failure to engage publics effectively on emerging and potentially controversial climate intervention research can stymie technological development itself (Low et al., 2022; Oksanen, 2023). The Stratospheric Controlled Perturbation Experiment (SCoPEx) was a proposed solar geoengineering research experiment that provides a critical case study of the dynamics between public engagement and research on emerging technologies. The SCoPEx research team made the decision to move forward with an engineering test flight in northern Sweden in 2021 without doing any community engagement. The proposed test flight was suspended for several reasons, including strong resistance from the local Indigenous community working in partnership with several national and international environmental NGOs (Jinnah, Talati, et al., 2024; Low et al., 2022; Oksanen, 2023). A key lesson to be learned from this proposed research experiment is that the meaning that many publics attach to climate intervention technologies is much broader than the potential for any immediate environmental impact of testing itself. In the SCoPEx example, the engineering test flight was not intended to release any particulate matter or result in any climate response. Yet, the testing of the engineering equipment without local consultation was sufficiently problematic that it contributed to the cancellation of that proposed experiment. In March 2024, the experiment was indefinitely suspended (Jinnah, Bedsworth, et al., 2024).

Although various factors contributed to this outcome, struggles around the nature of public engagement were evident (Tollefson, 2024). Core recommendations from the SCoPEx Advisory Committee on governance for outdoor experiments in the future include engaging with potentially impacted communities early before research plans are set and standardizing and possibly centralizing these processes across research projects (Jinnah, Talati, et al., 2024). While it is difficult to know if public engagement would have yielded a different outcome for SCoPEx, at a minimum, a good faith engagement effort likely would have mediated against the deep erosion of public trust that ensued in that case. This example also highlights why impacts should be evaluated as real or perceived when assessing the type or extent of engagement needed.

Similarly, a lack of engagement surrounding climate intervention activities and research featured centrally in the Mexican government’s January 2023 statement on its intent to ban all solar geoengineering experiments in Mexico (Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources, 2023) and the decision of local authorities to shut down an April 2024 marine cloud brightening experiment in Alameda, California (Karlamangla & Flavelle, 2024).

CDR also provides lessons for public involvement in the research and deployment of emerging technologies in the United States. CDR technologies are moving rapidly from a concept in models and laboratory-stage technological readiness to demonstration-scale projects, largely without widespread public involvement. Some of these projects, such as the U.S. Regional Direct Air Capture Hubs5 funded through the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), are aimed at learning. Yet in public discourse, research-driven demonstration programs for CDR are often conflated with controversial commercial projects that involve carbon management (e.g., Baptista & Ventrella, 2022; Food & Water Watch, 2022); they are not necessarily seen as research activities but rather as subsidies for industry. For many of these projects, regulatory hearings around pipeline or well injection permitting are the first opportunities for engagement that the public has to weigh in about the desirability or design.

This example further highlights how public engagement needs dedicated resources much earlier in a project, ideally in the conceptualization stages before project siting. The wider literature on engagement with energy projects also emphasizes that early engagement is important for addressing power differences between participants and ensuring real influence on decision making and outcomes, as well as addressing the framing of the engagement itself (Suboticki et al., 2023). This applies to CDR, solar geoengineering, and atmospheric methane removal, as well as to new technological infrastructure more generally. Some lessons for public engagement include the following:

- While experts may make distinctions about a technology being used for a particular climate goal, people on the ground are also concerned about particular impacts such as perceived risks to air and water quality.

- Developing research programs and deployment incentives at the same time—for example, providing tax credits for carbon dioxide (CO2) sequestration while

___________________

- also providing federal funding for research on CDR—is legitimately confusing for publics as to whether the aim is to research or immediately deploy these technologies.

Lessons from the literature and empirical experience with engagement for technology deployment suggest that many factors will impact the demand for engagement with relevant parties. For example, demand for engagement likely would increase as the scale of the intervention increases; when there are high levels of uncertainty about a technology; when potential impacts are perceived as potentially high; and/or when people see a technology as “tampering with nature,” having irreversible impacts, and/or resulting in lock-in or moral hazard (Chhetri et al., 2018; Grubert, 2024). However, experiences from solar geoengineering and hydraulic fracturing caution that even if the direct environmental impacts may be very small for a specific experiment or activity, public perception of risk can be large based on expectations about what the technology could be if ever scaled in the future (Grubert, 2024; Low et al., 2022; Oksanen, 2023). The literature suggests that a strong predictor of technological risk perception (and acceptance) is the extent to which a project is perceived to be tampering with nature, which might include elements such as ideological concerns, degree of controllability over the technology, and how “natural” the technology is perceived to be (Hoogendoorn et al., 2021). Additional research is needed to determine what constitutes small- versus large-scale experiments for each atmospheric methane removal technology, the impact levels of uncertainty that trigger more extensive engagements, the perception of the extent to which various technologies tamper with nature, and the conditions that increase public demand for particular types or levels of engagement (see Chapter 6).

Conclusion 5.2: Large uncertainties remain about the potential social impacts of all atmospheric methane removal technologies, and little is known about what perspectives will begin to emerge among the public. In line with recommendations from social science research, public engagement will be critical to informing decision making on technological development and/or deployment.

- Drawing on lessons from other climate intervention technologies, early and broad public engagement would help shape research and research governance in the public interest and ameliorate negative consequences. Recent experience with proposed experiments suggests that a lack of engagement can contribute to the cancellation of potentially valuable experiments.

- Engagement with relevant parties and communities will be important for all atmospheric methane removal technologies, especially open system technologies, prior to consideration of deployment and in tandem with ongoing small-scale research.

Public Perspectives

Increasing and continually updating the knowledge base about how different individuals and groups perceive atmospheric methane removal is critical for supporting

governance and decision making as well as technology development. The Committee refers to the broad pursuit of trying to understand how different individuals and groups perceive atmospheric methane removal as atmospheric methane removal perspectives research (or simply “perspectives research,” adapted from the analogous term used by Dove et al. (2024) to encompass research about perceptions of other climate-intervention strategies).

The Committee uses the term “perspectives” to include cognitive (e.g., understanding), evaluative (e.g., approval or disapproval), and motivational (e.g., support or opposition) dimensions. The term therefore encompasses many more specific constructs in relevant literature (e.g., perceptions, construals, interpretations, understanding, evaluations, judgments, support and opposition, and approval and disapproval). The term “perspectives” is broader than and independent from “social license.” Depending on the content of the relevant parties’ perspectives, a given project may or may not receive social license (i.e., consent) to operate; and social license may or may not be rooted in active support. The term “perspectives” also acknowledges that individuals, communities, and groups may differ in which aspects of atmospheric methane removal they focus on or care about and that those views may change across contexts or over time.

Though discussed separately, public perspectives, governance, public engagement, environmental justice, and technology development are connected and likely to affect one another in interactive ways. For example, initial perspectives may shape early governance decisions: relatively more positive perspectives may promote more facilitative governance approaches, whereas relatively more negative perspectives may promote more restrictive governance approaches. Inversely, the extent to which governance approaches promote early-stage (versus late-stage) and broad (versus narrow) public engagement likely will shape which perspectives are reflected in dominant public narratives. For example, who is consulted will directly determine which perspectives are represented.

The Committee could identify no published systematic studies to inform public perspectives of atmospheric methane removal. While some work explores perceptions of “unconventional gas development” in the United States (Brasier et al., 2013; Graham et al., 2015) and other work explores support for methane regulation in Europe (Bergquist & Mahdavi, 2023), no work has been published yet on the potential removal of methane from the atmosphere. As relevant studies begin to form a literature, it is important to remember that perspectives are likely to be a moving target. Even within the scientific community, atmospheric methane removal is a new idea. In public discussions, its formal and informal meanings have not yet been established. The Committee therefore considers “atmospheric methane removal” and related constructs, such as “atmospheric oxidation enhancement” and “methane reactors,” to be “emerging attitude objects”—meaning that they are in the process of being socially defined (Stern et al., 1995).

People form attitudes and perspectives about new ideas by looking externally to their communities and other trusted information sources to try to determine what implications the object has for their own most cherished values (Schultz & Zelezny, 1999; Stern et al., 1995, 1999). Yet, while those core values are relatively stable (Schwartz, 1992), the perceived implications of the idea (e.g., an emerging technology) for those

values may be relatively malleable, depending on how people subjectively interpret emerging narratives, norms, and frames (Kahan et al., 2015; Whitmarsh et al., 2019) and on how they understand descriptions of the complex systems involved (Fischhoff, 1989; Weber & Stern, 2011). It is important to note that even as scientific understanding of atmospheric methane removal develops, public understanding may evolve differently. According to Weber and Stern (2011), physical, psychological, and social factors contribute to this divergence:

First, climate change as a set of physical phenomena in interaction with their human causes and consequences is intrinsically challenging to understand. Second, scientists and nonscientists have different ways of understanding these phenomena, which makes divergence of beliefs possible. Moreover, when people apply their conventional modes of understanding to climate change, they are likely to be misled. Third, nonscientists’ views in the United States and some other countries are being shaped by an ongoing struggle to impose conceptual frames on climate change as a policy issue.

As an illustration of how much complexity and malleability must be accounted for, consider that even attitudes about methane itself depend on what it is called, with a sample of American respondents indicating more positive feelings about “natural gas” than about “methane” or a variety of closely related terms (Lacroix et al., 2021). These terms also brought different uses and consequences to mind among representative samples of German, French, Italian, and Polish respondents (Bergquist & Mahdavi, 2023). For instance, respondents were more likely to associate home heating and cooking with “natural gas” than with “methane,” and more likely to associate air pollution and greenhouses gases with “methane” than with “natural gas.”

If feelings about the chemical compound itself can be affected by mere changes to the term that describes it, this suggests that significant variance should be expected when accounting for different individuals (e.g., personality, values, culture), situations (e.g., group contexts, norms, emerging narratives), and temporal dynamics (e.g., changing environmental, political, and scientific contexts). Therefore, it may be useful to pursue a process-oriented understanding that asks not just “what” people think about methane removal but also “how,” “when,” and “why” they arrive at the judgments they do (Converse et al., 2021; Wilson, 2022). Focal determinants might include individuals’ higher-order values (Rokeach, 1973; Schwartz, 1992); prominent frames, narratives, and social interpretations (Snow et al., 1986; Stern et al., 1999); and individuals’ shifting understanding of the benefits, costs, and risks (Dietz & Stern, 1995; Slovic, 1987; Wildavsky & Dake, 1990).

Daily practices and experiences are likely to matter as well. For example, researchers have reasoned that “methane is distinct from other greenhouse gases in at least four ways that may imply differences in public attitudes and reactions to … policy framing” (Bergquist & Mahdavi, 2023). One difference is that methane can be economically useful as an energy and heating source, whereas other greenhouse gases (GHGs) like CO2 and nitrous oxide (N2O) are externalities. A second difference is that many consumers have direct personal experience with using methane, such as when they cook

with natural gas. A third difference is that methane can lead to localized health effects, making it possible that some perceivers will think of its consequences like those of soot and particulates. And a fourth difference is that methane may feature differently in security-policy discussions than other GHGs.

While no studies could be identified that have examined atmospheric methane removal perspectives, many studies examine perspectives on climate-intervention strategies (such as solar geoengineering and CDR) and other emerging climate technologies (for reviews, see Cummings et al., 2017; Raimi, 2021; Smith et al., 2023). Though this literature has major blind spots—such as severe underrepresentation of samples from the Global South (see Dove et al., 2024; Sovacool, 2023; see also Baum et al., 2024)—it nonetheless increases confidence that judgments of climate-intervention strategies vary along predictable dimensions, and it therefore highlights some key questions for atmospheric methane removal, which will be elaborated in Chapter 6.

Conclusion 5.3: No data are available about public perception of atmospheric methane removal.

Environmental Justice

Environmental justice is a concept, a movement, an aspiration, and a field of scholarly research and practice. Common definitions, such as the definition used by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), emphasize the just treatment and meaningful involvement of all people in activities that affect human health and the environment, and protection from disproportionate and adverse environmental effects and hazards (Institute of Medicine, 1999). In 1991, the First National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit adopted 17 principles of environmental justice6 that remain foundational to the movement today. Climate justice is a more recent movement that understands climate as a human rights and racial justice issue, particularly as the impacts of climate change have disproportionate impacts on marginalized communities (Environmental Justice Leadership Forum on Climate Change, n.d.). Indigenous environmental justice has been articulated as a distinct framework that draws on Indigenous knowledge systems for transformative change (McGregor et al., 2020); it attends to how Native nations are government entities, have connections to traditional homelands, and endure the continuing impacts of colonization (Jarrat-Snider & Nielsen, 2020).

At least four different dimensions of justice are relevant to environmental justice in the context of emerging technologies to address climate change: procedural justice refers to fairness in the decision-making process (Yale Law School, n.d.); distributive justice refers to the equitable allocation of resources, risks, and benefits (Lamont & Favor, 2017); reparative justice repairs previous harms (Greyl et al., 2013); and inter-generational justice refers to fair treatment of future generations (Meyer, 2021). Though specific atmospheric methane removal technologies will have different environmental justice implications, the development or pursuit of any technological approach (or

___________________

decision not to develop or pursue any technological approach) ought to strive for just processes and outcomes on these dimensions.

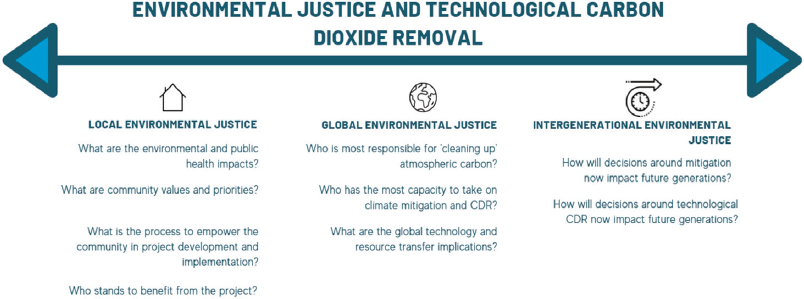

CDR and carbon management provide examples of the types of environmental justice issues that can arise around emerging climate technologies. Environmental justice communities have raised concerns about CDR, including the following: CDR can distract from meaningful emissions reductions; extractive industries are investing in CDR; there are uncertainties in the non-climate trade-offs and benefits from CDR; diversity and representation are lacking in the climate action space (Suarez, 2023); and some initial demonstration projects are proposed for places such as the Gulf Coast that have been experiencing cumulative burdens or ongoing harms from industrial activity. Furthermore, Kosar and Suarez (2021) outline several case studies in which carbon management projects failed to meet the needs of frontline communities. Recent work has highlighted different dimensions and proposed guiding principles for the consideration of CDR in the context of environmental justice (e.g., Batres et al., 2021; Kosar & Suarez, 2021; Morrow et al., 2020) (see Figure 5-2). The local, global, and intergenerational justice dimensions highlighted in Figure 5-2 will all be relevant to decisions about atmospheric methane removal research and/or development.

It should also be noted that what constitutes justice can be contested. For example, in the solar geoengineering context, scholars have diverging opinions about whether such technologies are fundamentally justice-degrading. This debate has been especially enflamed as it applies to whether solar geoengineering is fundamentally unjust for climate-vulnerable communities in the Global South (Parson et al., 2024). Although open letters and unsubstantiated opinions abound, limited empirical research has been done on this topic. Nonetheless, existing preliminary research demonstrates that actors in the Global South show greater support for the exploration of climate intervention technologies, such as solar geoengineering, than do some of their Northern counterparts (Baum et al., 2024; Contzen et al., 2024; Low et al., 2024; Sugiyama et al., 2020). Similar questions likely will arise in the context of open system atmospheric methane removal technologies. The findings of Baum et al. (2024) and others underscore the importance

SOURCE: Batres et al. (2021).

of engaging global actors before making determinations about what constitutes justice on their behalf and before implementing restrictive moratoriums or bans on research that global publics might not support.

Conclusion 5.4: Given the nascency of atmospheric methane removal research, little in the academic literature discusses the potential environmental justice implications of atmospheric methane removal technologies under different policy and deployment arrangements or scenarios. Evidence is also lacking about how different publics may understand justice in their specific contexts, and conclusions cannot be drawn in the absence of empirical research. Nonetheless, experience with other climate intervention technologies suggests that environmental justice concerns will be important and should be addressed proactively.

OTHER SOCIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Other social considerations that are not directly encompassed by governance, engagement, perspectives, and justice would be relevant if atmospheric methane removal technologies develop. Cost will be not just an economic factor but also a social and political consideration, in terms of who pays for atmospheric methane removal and how to ensure that the costs are not regressive; this applies to climate policy broadly. Formalized frameworks to assess the social impacts of specific projects or policies do exist (see Box 4-4), though their application may not be standardized in practice (Grubert, 2024). Efforts to incorporate social impacts into the life-cycle assessment (LCA) framework also exist (see Box 4-3), though these technologies are still in a state of development.

Political economy, or the economic model and political environment in which atmospheric methane removal may be developed, is another social consideration. For some technologies, vested interests and actors who are already engaged in this space will be important in shaping the social impacts, in terms of whether policies to develop atmospheric methane removal technologies favor incumbent interests or support new actors and whether atmospheric methane removal is developed by the public or private sectors or collectively. Transparency of both data and R&D funding sources will be considerations, in terms of accountability and the legitimacy of efforts to develop atmospheric methane removal technologies. Labor and workforce considerations similar to those in climate technology and environmental management—for example, training a sufficient workforce, ensuring quality jobs, and ensuring equitable access to job opportunities—will arise if atmospheric methane removal technologies scale. At this state of technological maturity, these considerations are mostly too speculative to address through empirical or theoretical research (except for the consideration of transparency of data, which intersects with both engagement and justice). The considerations are raised here as areas of future research should atmospheric methane removal technologies prove worthy of further attention (see Chapter 6).

POLICY LANDSCAPE FOR ATMOSPHERIC METHANE REMOVAL

Policy interventions, both domestically and internationally, have the capacity to facilitate—for example, through financial investments and incentives—or constrain—for example, through regulations—atmospheric methane removal research and/or development. Chapter 2 introduced the policy landscape for methane emissions mitigation and CDR. Building on that landscape, the sections below outline policies that may be relevant for atmospheric methane removal: first, domestic and international legal and regulatory frameworks; second, market-based mechanisms; and third, monitoring, reporting, and verification (MRV).

Legal and Regulatory Frameworks Relevant to Atmospheric Methane Removal

While there are no specific legal frameworks internationally or domestically in the United States that govern atmospheric methane removal, many existing international agreements and domestic laws may be relevant. Silverman-Roati and Webb (2024) analyzed potentially relevant international and U.S. domestic laws and considerations for different atmospheric methane removal technologies, and key issues are highlighted below.

In general, open system technologies—surface treatments, ecosystem uptake enhancement, and atmospheric oxidation enhancement (AOE)—are more likely to be subject to cross-jurisdictional legal frameworks, including prohibitions on environmental harm and governance of the ocean. Specifically, land- and ocean-based AOE likely would be subject to federal or international legal frameworks (Webb et al., 2024). Due to the potential for more widespread impacts, more extensive consultation may be required as part of environmental reviews, and open system technologies may have more legal exposure. The potential also exists for international bodies or countries to set thresholds to categorize open system technology projects as research (and therefore permitted under certain circumstances) versus deployment (and possibly restricted). For example, the European Union issued the Directive on the Geologic Storage of Carbon Dioxide, which defined a threshold of 100 kilotonnes of CO2 storage to distinguish between field testing research (below 100 kilotonnes) and commercial deployment (above 100 kilotonnes).7

From a legal standpoint, whether activities occur over land or over or in the ocean is also relevant. Over or in the ocean, the relevant legal or regulatory requirements are determined by how far offshore an activity occurs in accordance with the United Nations Convention of the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). Each coastal country has full sovereignty over the waters within, the seabed below, and the airspace above its territorial sea within 200 nautical miles (nm), subject to UNCLOS and other rules of international law; ocean waters more than 200 nm from shore are subject to the freedoms of the high seas and

___________________

7 Directive 2009/31/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 April 2009 on the Geologic Storage of Carbon Dioxide and Amending Council Directive 85/227/EEC; European Parliament and Council Directives 2000/60/EC, 2001/80/EC, 2004/35/EC, 2006/12/EC, 2008/1/EC, and Regulation (EC) No 1013/2006.

subject to international law (Silverman-Roati & Webb, 2024). Atmospheric methane removal projects that are conducted in or could impact the marine environment would need to comply with Part XII of UNCLOS, which imposes a general obligation on countries to “protect and preserve the marine environment” and a duty to monitor the activity and its effects on the marine environment (Silverman-Roati & Webb, 2024).

The Convention on the Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping of Wastes and Other Matter (London Convention) and subsequent Protocol (London Protocol) is an international agreement to protect the marine environment from all sources of marine pollution—and, specifically, to prevent the pollution of the sea by the dumping of wastes and other matter—and that pertains to activities over the ocean that could be relevant to some atmospheric methane removal technologies. The Contracting Parties to the London Protocol agreed to a legally binding amendment in 2013 establishing a regime for activities involving the “placement of matter into the sea” for the purposes of “marine engineering,”8 though this amendment has not yet entered into force. To date, only ocean fertilization is listed as a marine geoengineering activity subject to the permitting regime, but other CDR and solar geoengineering activities are being considered (Webb, 2023). Atmospheric methane removal technologies that could lead to ocean fertilization—namely, through AOE approaches that add iron salt aerosols to the atmosphere—could be listed in the future (Silverman-Roati & Webb, 2024). The United States is not a Contracting Party to the London Protocol; it is only a Contracting Party to the older London Convention.

In contrast, closed system technologies—methane reactors and methane concentrators—may be relatively less complex with key legal considerations around land acquisition and environmental impacts, which may impact where proponents may site projects for testing and deployment (i.e., jurisdictions with favorable legal frameworks). For example, land-based activities in the United States would be subject to the appropriate federal, state, local, and tribal jurisdictions, which have impacted the cost and timeline of CDR projects (Pacyniak, 2023; Parker, 2022; Silverman-Roati et al., 2022a).

Conclusion 5.5: To the Committee’s knowledge, no specific legal frameworks are directed at governing atmospheric methane removal. Atmospheric methane removal may be subject to a variety of existing international agreements or domestic laws based on the activities involved and/or their collateral environmental or other impacts.

Assessing the Role of Market-Based Mechanisms in Research, Development, and Deployment of Atmospheric Methane Removal

Price on Methane Emissions

The main argument for using market-based approaches in responding to climate change is that they can motivate adoption of technologies and stimulate innovation. In

___________________

8 Resolution LP .4(8), Amendment to the 1996 Protocol to the Convention on the Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping of Wastes and Other Matter, 1972 to Regulate Marine Geoengineering (Oct. 18, 2013).

theory, carbon pricing can shift the behavior of consumers, producers, investors, and innovators at the same time (van den Bergh & Botzen, 2020). One direct financial incentive mechanism for methane removal would be a price on GHG emissions. Recent steps have been taken in the United States toward a structure for valuing and pricing methane emissions. The IRA creates a charge for methane emissions exceeding percentages of fossil fuels sent for sale from a production facility, with these excess emissions charges beginning at $900 per metric ton of methane in 2024 and rising to $1,500 per metric ton in 2026 (Congressional Research Service, 2022). U.S. EPA has proposed a rule for implementing this Waste Emissions Charge.9 Additionally, in 2021, the U.S. Government Interagency Working Group on the Social Cost of Greenhouse Gases released its social cost estimates for methane, with a 3 percent discount rate average of $1,500 per metric ton (IWG, 2021). Specific markets that credit methane reductions have arisen in recent years, some of which are discussed in the following sections.

While recognizing and supporting the use of incentive-based programs to attain emissions reductions, the National Academies Committee on Accelerating Decarbonization in the United States also recommends, in both its first and second reports (NASEM, 2021a, 2023), drawing on an even broader suite of not only incentives but also taxes, regulatory standards, and statutes for creating new institutions or entities for attaining necessary GHG reductions to facilitate an equitable and just transition to net-zero U.S. GHG emissions by 2050.

Status of Carbon Markets

Carbon credits and carbon offsets are accounting mechanisms that can be bought and sold as part of carbon markets and generally represent a reduction in or removal of GHG emissions that compensate for CO2 emitted somewhere else. Carbon credits are a measurement unit to permit a certain amount of GHG emissions and are generally transacted in the carbon compliance market (e.g., regulatory emissions trading scheme). Carbon offsets are created by investments in projects that reduce GHG emissions elsewhere (e.g., reforestation, renewable energy projects) and are generally transacted in the voluntary carbon market (e.g., purchased by consumers to offset emissions from a flight).

Methane is already involved in carbon markets in two ways. Methane is occasionally covered in regulatory markets (i.e., as emissions that require offsetting). Methane emissions are at least partially covered under at least seven domestic emissions trading systems (California, Chongqing province in China, Quebec, Nova Scotia, New Zealand, South Korea, and Switzerland), and most emissions trading systems cover methane from energy and industrial processes; South Korea and New Zealand also include emissions from the waste sector (Olczak et al., 2023). Methane mitigation in agriculture has largely been voluntary to date.

Moreover, methane mitigation activities are already a source of carbon credits (i.e., they can offset CO2 emissions from other sectors and activities). The Kyoto Protocol

___________________

9 See https://www.epa.gov/inflation-reduction-act/waste-emissions-charge.

established the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), a widespread voluntary carbon market that allows developing countries to earn tradable certified emissions reductions. There have been more than 7,000 CDM projects to date; several of them relate to reducing methane emissions, such as landfill gas capture and methane abatement from coal mines (Singh et al., 2022). Voluntary markets also have methodologies, developed by nonprofits, that deal with methane—for example, the American Carbon Registry publishes standards, methodologies, and protocols for projects involving livestock, landfills, and coal mines, and the Verified Carbon Standard program has registered 46 coalbed methane projects (Singh et al., 2022).

The main methane mitigation activities that generate carbon offsets are landfill gas projects, anaerobic digesters at dairies, and coal mine mitigation projects. For a sense of the scope of this activity, as of 2021, 550 landfill gas energy projects were underway in the United States alone, with about 70 percent of them generating electricity. Moreover, 416 manure-based U.S. anaerobic digesters were projected to be operational in 2023 (O’Hara et al., 2023). Credit sales from offset programs provide an incentive to install this infrastructure, which can be capital-intensive, but environmental market credits could be subject to price fluctuations and regulatory uncertainty (O’Hara et al., 2023).

At the time of this report’s writing in early 2024, carbon markets are at an inflection point. While carbon offset projects have been criticized for years—for example, for limited delivery of benefits to local or Indigenous communities (Mathur et al., 2014); increased violence within communities, especially communities with existing conflicts (Howson, 2018; Lyons & Westoby, 2014; Schmid, 2023) and violence caused by companies via the dispossession of local peoples (Cavanagh & Benjaminsen, 2014); and the failure to comply with expectations of free, prior, and informed consent (Milne & Mahanty, 2019)—the level of criticism in 2023 impacted companies and is translating into a decline in demand (Temple, 2023). The remainder of this section outlines current challenges with carbon markets and carbon removal markets, with implications for the treatment of methane or methane removal in these market-based mechanisms.

While carbon markets are central to global climate policy, literature assessing their efficacy is scarce. According to a recent evidence synthesis report by the Science Based Targets initiative, evidence submitted did not identify characteristics or operating conditions associated with effective carbon credits and projects (Borjigin et al., 2024). Empirical studies found that many CDM projects credited large numbers of non-additional projects (i.e., projects that do not result in additional emissions reductions) or created perverse incentives that increased emissions (i.e., profits generated by offset sales from hydrofluorocarbon destruction projects that were large enough to create an incentive for refrigerant producers to generate more by-product that could be destroyed to generate offset credits) (Haya et al., 2020). More broadly, a recent meta-review that quantitatively evaluated the impacts of carbon pricing policies since 1990 found that only 37 studies assess the actual effects of carbon pricing on emission reductions, mainly in Europe, and suggest that the aggregate reductions from carbon pricing on emissions are limited, generally between 0 and 2 percent per year (Green, 2021).

Four main issues with voluntary carbon offsets have emerged in the first few decades of their use: (1) leakage, meaning that economic activity subject to carbon pric-

ing shifts to a jurisdiction without those regulations (Green, 2021); (2) impacts on local people—for example, communities being displaced from land for forest conservation or failing to receive financial benefits from carbon projects (Aggarwal & Brockington, 2020; Kemerink-Seyoum et al., 2018; Schmid, 2023); (3) fraud, because carbon credits are “credence goods” (goods with qualities that cannot be ascertained by consumers even after consumption), with well-documented challenges in the economics literature (Kerschbamer et al., 2016); and (4) baselines, or establishing that emissions reductions are additional to what would have happened without the offset, which is a counterfactual scenario and cannot be “validated.” While stronger regulation and safeguards theoretically could lead to improved outcomes with regards to leakage, impacts on communities, and fraud, the fundamental challenge with proving the additionality of offsets remains.

Challenges with voluntary carbon markets have been recognized not just by researchers and civil society organizations but by policymakers as well. For example, in the United States, the White House and federal agencies issued Voluntary Carbon Markets Joint Policy Statement and Principles in May 2024, which emphasized principles around climate and environmental justice, credible credit use, and market-level integrity (The White House, 2024b). While these are very high-level principles, they set a floor of expectations and point to wider recognition of issues that are arising with voluntary markets.

Existing programs illustrate these challenges in relation to credits for methane mitigation. For example, California’s Low Carbon Fuel Standard, one of the main crediting programs for dairy digesters, offers digesters credits for avoided methane emissions (O’Hara et al., 2023). California’s policy around digesters has come under scrutiny for several reasons. First, critics argue that its contribution to addressing methane emissions from livestock is minor, and environmental justice advocates are concerned about technology lock-in (Mosavi, 2023). Second, researchers have identified perverse incentives in which the program for offset credits is likely to lead to the unintended consequences of increasing the profits of high-emitting activities (Haya et al., 2020). Third, these offset schemes face the same issue that carbon markets do in terms of additionality and baseline. For example, California passed Senate Bill 1383 in 2016, which set requirements to reduce methane emissions by 40 percent relative to 2013 levels by 2030. This new regulatory requirement means that companies will no longer receive credits for reducing methane emissions because the reductions would not be additional to those already required under law.

Examining the existing landscape of methane mitigation offsets highlights the challenge of introducing atmospheric methane removal in the context of net-zero goals without being able to distinguish removal from emissions mitigation, and the importance of creating clear definitions and safeguards around additionality in policy. For example, as discussed in Grubert (2024), if a hypothetical natural gas company has high methane emissions due to a malfunctioning flare, requiring methane mitigation would incentivize repairing the infrastructure. If methane destruction was defined as atmospheric methane removal, and offset markets enabled this, the company theoretically could sell atmospheric methane removal–based negative emissions credits for doing what it should simply be doing under a stronger regulatory regime.

Greenhouse Gas Removals in Markets

Given the current challenges with carbon offsets, some analysts have suggested moving to a carbon removals market, which would require that emissions not be offset by avoided emissions elsewhere but be compensated for by removals. The idea of carbon offsets emerged during the Kyoto Protocol–era in the late 1990s and early 2000s when little mitigation action occurred, and incentives were needed to reduce emissions. Today, this Paris Agreement–era climate policy challenge is about not just reducing emissions but also zeroing them out—that is, reducing emissions nearly completely and compensating for residual emissions with CDR. Being Paris Agreement–aligned means that emissions-reducing carbon credits could not continue to be used as offsets because through their use, the remaining carbon budget continues to shrink; therefore, the logic of treating emissions reductions credits the same as removals may not be effective toward meeting contemporary climate policy goals (Arcusa & Sprenkle-Hyppolite, 2022).

Currently, accounting for carbon removals in carbon market arrangements is challenging, with a complex ecosystem of removal-specific private standards and marketplaces. A recent review found that in 2021–2022, at least 30 standards-developing organizations were proposing at least 125 methodologies for 23 different CDR approaches and selling 27 different versions of certification instruments in voluntary and compliance markets (Arcusa & Sprenkle-Hyppolite, 2022). The Paris Agreement Article 6 process does address removals, so those ongoing United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change negotiations are expected to lead to an international framework for dealing with removals. Under the Article 6.4 mechanism of the Paris Agreement that creates a centralized trading mechanism, a subsidiary body issued an “information note” in May 2023 questioning whether non-CO2 GHG removals should be considered as part of this mechanism (Silverman-Roati & Webb, 2024). Such definitions have implications for both potential market-based incentives as well as how governments might rely on GHG removals to achieve their emission reduction targets.

It is not yet clear whether existing GHG markets, crediting schemes, and removal marketplaces are making a measurable difference in responding to climate change. Introducing nascent atmospheric methane removal technologies into these markets will face challenges similar to those described above, whether an atmospheric methane removal market is conceptualized as an extension of existing credits for methane mitigation or as an extension of carbon removal markets. Further research will be needed to better understand which policy options will be most effective at supporting innovation in atmospheric methane removal (see Chapter 6).

Conclusion 5.6: At present, offset markets are used to scale carbon removals and methane emissions mitigation. If atmospheric methane removal technologies were to enter offset markets, additional fundamental policy research and monitoring, reporting, and verification requirements would be essential to ensure that they would contribute to additive reductions in atmospheric methane concentrations.

Conclusion 5.7: Better understanding of the efficacy of greenhouse gas offset and removal markets in delivering net climate benefits is needed.

Measurement, Monitoring, Reporting, and Verification

Improving measurement and MRV of methane emissions and removals across all sectors is one of the high-level recommendations of the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology (PCAST, 2024). This need is particularly important as the United States develops the Greenhouse Gas Measurement, Monitoring, and Information System described in Box 2-2. As discussed in Chapters 3 and 4, assessing the potential of atmospheric methane removal technologies to deliver climate-scale benefits requires appropriate measurement and quantification of the methane removed, as well as mechanisms for continued monitoring of the performance of the removal technology and any unintended physical consequences. Reporting and verification mechanisms would need to be developed as a function of the context in which atmospheric methane removal is operating. For example, in a research context, the technology may need to report on specific performance benchmarks. In regulatory or market contexts (discussed above), verification is an essential component of determining the reliability of reported results.

Measurement

To quantify the amount of methane removed, all atmospheric methane removal technologies would require measurement of methane concentration or mole fraction before and after treatment. To measure atmospheric methane removal technologies toward the goal of MRV requires instruments that have minimum detectible limits that are more accurate than the amount of methane in the atmosphere—namely, instruments with better than 0.1 ppm accuracy. Such instruments currently exist (e.g., methods based on cavity ring-down spectroscopy or gas chromatography); however, the application of these methods to atmospheric methane removal technologies is challenging. For example, if the measurement instrument is based on a mole fraction measurement (e.g., gas chromatography) and not a concentration measurement, then the associated flow rate of the gas processed must also be quantified accurately to determine the total amount of methane removed (e.g., mass of methane removed per unit time).

In general, measurements for partially closed system technologies would involve measuring the flux of methane entering and exiting the reactor at a level of precision sufficient to detect the change in methane reliably and reproducibly. For application to partially closed system technologies, measurement devices are commercially available for analyzing gas concentrations at the ppb level (e.g., cavity ring-down absorption spectroscopy). Open systems may present greater challenges for accurately measuring methane removal because these atmospheric methane removal technologies operate with larger air masses where removal occurs more diffusely than in partially closed systems. However, larger open systems provide good access for physical-sampling techniques and good optical access and long path lengths for spectroscopic methods. As an example, eddy-flux systems may be appropriate in some ecosystem uptake enhancement and

surface treatment contexts but would need to be designed to meet the specifications of the research context (i.e., sensitivity, temporal and spatial resolution, etc.).

All atmospheric methane removal technology applications will need analytical measurement methods that provide statistical confidence in the results—for example, taking into consideration averaging and diffusion effects if long-path lengths are required, or scaling if local or point measurements are used. Some atmospheric methane removal technologies (e.g., chlorine-based AOE) will require local as well as global detection of methane concentration changes, making the measurement problem more difficult. Generally, small changes in diffuse air masses present the greatest measurement challenge. While partially closed system technologies would require measuring the flow rate of air and the change in concentration, open system technologies, such as AOE, require measuring the volume or mass of air impacted and the change in concentration—typically a much harder measurement to conduct accurately at low cost (requiring more and more expensive measurement instruments).

Some instruments that measure methane are based on extractive sampling and ex situ analysis (e.g., flow sampling followed by gas chromatography), while others leverage in situ measurement methods (e.g., line-of-sight absorption spectroscopy). Both extractive and in situ technologies have merits and challenges. Depending on the atmospheric methane removal technology, different measurement resolutions may be required to capture local variations over space and time. While several methods have been demonstrated for leak detection of high concentrations of methane (e.g., natural gas pipeline leaks), the same instrumentation is not likely to be well suited for atmospheric methane removal technologies due to the orders of magnitude lower concentrations of methane in the atmosphere. Thus, development of diagnostic tools for low or diffuse methane concentrations likely is required in parallel with atmospheric methane removal technology research (see Chapter 6).

An additional measurement challenge for atmospheric methane removal technologies is the oxidative capacity of the atmosphere, which will be impacted in complex, nonlinear ways by large-scale deployments of any atmospheric methane removal technologies (see Consequences for Atmospheric Composition). The hydroxyl and chlorine radicals responsible for most of the atmospheric methane sink cannot be measured directly because of their short atmospheric lifetime (on the order of seconds). The oxidative capacity of the atmosphere has been inferred by measuring the decrease in atmospheric concentration of methyl chloroform. However, as methyl chloroform concentrations have decreased since the 1990s (see Chapters 2 and 3), the precision with which methyl chloroform can be measured decreases, thus reducing the precision of the inferred oxidative capacity. New methods of measuring and monitoring the oxidative capacity of the atmosphere at higher spatial and temporal resolution would be needed for MRV of all atmospheric methane removal technologies (see Chapter 6).

Monitoring

Instruments are commercially available for measuring methane concentrations that are portable and accurate at the scales at which they operate; however, they are

expensive and may not operate at the scale necessary to monitor methane removal from open system technologies accurately, precisely, and continuously. Remote sensing of high-concentration methane sources continues to improve in geographic and temporal coverage with multiple satellite systems in operation and planned for launch in 2024 and beyond (e.g., Chulakadabba et al., 2023; Cusworth et al., 2022; Jacob et al., 2022; NASEM, 2022c; Thorpe et al., 2023). Area flux mappers with high-precision instruments that image large regions combined with fine-pixel point-source imagers are improving detection and quantification of methane emissions from large point sources with fluxes down to about 100 kg of methane per hour (Jacob et al., 2022). While these systems will improve understanding of the methane budget, they are unlikely to have the sensitivity required to monitor atmospheric methane removal at any scale foreseeable with the technologies assessed in this report. Tower-based eddy covariance measurements can provide ecosystem-scale methane fluxes at high temporal resolution; however, spatial coverage is limited (Delwiche et al., 2021). Efforts such as FLUXNET-CH410 could be expanded to cover more regions and ecosystems but would require financial support. Monitoring of potential unintended consequences, particularly the production of non-target gases, should be considered too, especially in the context of open systems at the research scale (see Chapter 4 and the following section).

Reporting

As atmospheric methane removal technologies increase in technology readiness level (TRL), developing consistent and robust standards for quantifying and reporting methane removal and, more specifically, differentiating emissions mitigation (prevention of emissions into the free atmosphere at the source) from atmospheric removal would be valuable.

Verification

PCAST (2024) calls for incorporating verification using atmospheric approaches to improve monitoring and reporting of methane sources and removals from all sectors. NASEM (2022c) detailed the importance of evaluation and validation for the development of useful and trustworthy GHG emissions information. Developing verification mechanisms becomes particularly important should atmospheric methane removal technologies be considered safe and viable for deployment in a regulatory or market context (see previous sections). The development of MRV for CDR offers possible lessons and analogies. However, while permanence (i.e., durable storage) is important for CDR, continuity of methane removal rate (e.g., effective methane removal metric in Abernethy et al. [2021]) is more relevant in the context of methane removal.

Conclusion 5.8: Researchers lack tools and/or capabilities that are affordable, accurate, precise, portable, and otherwise robust for field-scale application of monitoring,

___________________

10 See https://fluxnet.org/data/fluxnet-ch4-community-product/.

reporting, and verifying the impacts of open system atmospheric methane removal technologies. More tools are available for monitoring, reporting, and verification for partially closed system technologies, although they are currently expensive and have limited scalability.

COSTS, TRADE-OFFS, AND RESOURCE USE

Atmospheric methane removal technologies carry costs from both capital and operational expenses. As with all investments, funds invested in atmospheric methane removal R&D could be spent elsewhere—for example, on other emerging climate technologies—presenting trade-offs for these financial resources. Additionally, as with all technologies, resources and inputs (e.g., energy) may be directed toward one application or one of its alternatives. This section outlines approaches for assessing the financial and energetic costs of atmospheric methane removal technologies and accounting for the trade-offs made in support these technologies as well as their resource use.

Cost Targets for Atmospheric Methane Removal Technologies

As discussed in Chapter 4, for climate change–driven technologies, technoeconomic assessment (TEA) should be conducted in parallel with LCA to assess both the costs and environmental impacts, particularly as these technologies continue to develop. The close integration of TEA and LCA enables the joint interpretation of identified key variables or hotspots (i.e., areas of the product life cycle with particularly high or meaningful impacts) and the balancing of trade-offs among technological, economic, and environmental aspects (Langhorst et al., 2022; Mahmud et al., 2021), especially as these technologies mature and more data on their operation become available. It is important to note that these costs are to be balanced against the potential benefits they yield. Abernethy et al. (2023) estimated an economic benefit of $600 (± $500) billion per year for a breakthrough technology (at a 3 percent discount rate, accounting for benefits from reduced temperature, improved air quality, and subsequent economic benefits) oxidizing all anthropogenic methane emissions, resulting in oxidation of all methane over 100 ppm. This is in comparison to an estimated benefit of $300 (± $200) billion per year for using all current commercial technologies to oxidize methane above 1,000 ppm.

More research on atmospheric methane removal is necessary before the technical, economic, and environmental performance of atmospheric methane removal technologies can be assessed quantitatively (see Chapter 6). Below, the Committee qualitatively describes the main variable costs of atmospheric methane removal technologies in partially closed and open systems.

Partially Closed Systems: Methane Reactors and Concentrators

With an atmospheric methane concentration of ~2 ppm, considerable volumes of air must be actively moved and processed to remove and/or convert a meaningful

amount of methane (see Chapter 4). Capital expenses (CapEx) associated with, for example, compressors/blowers, reactors, heat exchangers, separation units, and operating expenses (OpEx), particularly energy input, that are required to convert this ultralow concentration of methane are expected to be prohibitive.

Several studies have estimated the expenses associated with different types of methane reactors, as summarized here. An analysis of energy requirements for methane catalysis by Tsopelakou et al. (2024) found electrocatalysis in turbulent ducts to be the most energy-efficient approach (∼0.2 GJ/tonne CO2 equivalent [CO2e]) for new installations, with a total energy intensity of <1 GJ/tonne CO2e. The authors found photocatalysis to be moderately more energy-intensive and thermal catalysis systems to be very energy-intensive, requiring >100 GJ/tonne CO2e. Abernethy et al. (2023) concluded that the energy requirement for moving and heating air potentially limits the scalability of methane reactors at atmospheric concentrations (see also Chapter 4).

Modeling results from Sawyer and Plata (2023) calculate a photocatalyst reactor operating at costs of $3,100/tCO2e (and energy use of 5,100 J/m3). These costs are driven by artificial lighting, with a free light source at 100 percent efficiency decreasing costs to $1,200/tCO2e. Randall et al. (2024) model light-emitting diode photocatalysts with fan-driven airflow over a range of parameters, noting the very high quantum yields required to reduce costs to less than $100/tCO2e. Sawyer and Plata (2023) model a thermal catalyst reactor and show the heat exchanger as the key driver of cost, at $14,000/tCO2e (and energy use of 7,600 J/m3), though coupling with industrial waste heat could bring this cost down. Hickey and Allen (2024) estimate costs for thermal-catalytic oxidation ranging from $633,920/tCO2 (when valuing a change in the level of warming metric) to $27,044/tCO2 (when valuing a change in the rate of warming). These authors find costs for photocatalytic oxidation to range from $16,767/tCO2 (level of warming) to $703/tCO2 (rate of warming). As a point of comparison, a range of estimated costs for a direct air carbon capture and storage system is $100–300/tCO2 (Edwards et al., 2024).

Bioreactors can operate at or close to ambient temperatures, so their reactor heating requirement is significantly lower than that of reactors using thermocatalysts or photocatalysts. However, the reaction rate of methane conversion in bioreactors is low, and the process would still require high power to move and process massive amounts of air. To date, no reports in the literature show that bioreactors can operate at 2 ppm methane concentration, with the commercially viable concentration reported as 500 ppm (Abernethy et al., 2023). It is possible through genetic modification of methanotrophs and/or addition of other microorganisms that co-catalyst bioreactors could operate at 2 ppm methane concentration. However, the reaction rate of methane oxidation would need to be significant to overcome the expected high CapEx associated with the expected air processing requirements. Hickey and Allen (2024) estimate costs for enhanced oxidation through biofiltration to range from $4,976/tCO2 (level of warming) to $216/tCO2 (rate of warming).

Open Systems

Open systems likely would be less expensive to deploy because they are not physically bounded, rely on passive movement of air, and have lower energy requirements, resulting in a significantly lower CapEx than that of partially closed systems (see also Chapter 4). The main costs of open systems may be associated with OpEx, particularly the continuous amounts of material needed to enhance the removal of atmospheric methane to levels that have a climate-scale impact.

Surface treatments.

Surface treatments have the potential to be among the relatively lower-cost technologies for atmospheric methane removal. Chemo-, bio-, or photocatalysts could be deployed as surface treatments in open systems. However, as with methane reactors, research into reaction rates for chemo- and biocatalysts and apparent quantum yield for photocatalysts at relevant atmospheric concentrations is needed to determine potential removal rates (see Chapter 6). Durability, safety, and potential unwanted environmental impacts are additional challenges for surface treatment systems (see Chapters 4 and 6). Sawyer and Plata (2023) present a cost estimate for a passive solar photocatalyst roof at $700/tCO2e, with a possible cost of $300/tCO2e when using optimized panels. For a rooftop photocatalyst surface exposed to sunlight and natural airflow, Randall et al. (2024) estimated approaching $300/tCO2e, with high quantum yields. The costs were 30 percent for initial painting, 2 percent for the catalyst, and 60 percent for annual washing. The estimate using panels yielded a construction cost per square meter seven times higher than that for painting rooftops (Randall et al., 2024).

Ecosystem uptake enhancement.

This technology also may be among the relatively lower-cost options for atmospheric methane removal due to its application in ecosystems that are already managed by humans. Soil amendments have shown promise for enhancing methane uptake; however, none of these amendments have been tested at scale (see Chapter 4). Not enough is known about effectiveness, rate of methane removal, or other potential feedbacks (positive or negative) that would impact the rate of methane removal and overall climate impact, pointing to the need for further research (see Chapter 6).

Atmospheric oxidation enhancement.

The amount of iron salt aerosol, hydrogen peroxide, or other radical-generating species that may be needed for climate-relevant scales of AOE is one to several orders of magnitude larger than the current global production of these chemicals (see Chapter 4). More research is needed to understand the potential impacts and nonlinearities from the addition of different scales of radical-generating species to the atmosphere (see Chapter 6). Randall et al. (2024) estimated that $100/tCO2e removal costs could be attainable by dispersing 1 μm particulates in the lower (<1.5 km) troposphere, but the estimate was very sensitive to particle costs. A large threshold exists above which adding chlorine may be effective at removing atmospheric methane, but below that level methane increases (see Chapter 4). Importantly, this means that a large threshold exists for research testing or small-scale deployment that makes costs per ton not the most effective means for defining cost for this technology. Research into competing and unwanted reactions and the potential environmental and health risks is needed (see next section and Chapter 6).

Methane Removal Technology Analogs

As detailed in Edwards et al. (2024) and Chapter 4, while specific components of some methane removal technologies are more well developed, all the technologies considered are in the early stages of their research and/or development. To assess potential scaling and costs, Edwards et al. (2024) employ the Systematic Historical Analogue Research for Decision-making method for identifying analogs (Roberts & Nemet, 2022). Analogs for the technology types assessed by this Committee; their cost target and growth rate analogs; as well as relevant policy, opportunity, and barrier analogs identified by Edwards et al. (2024) are summarized in Table 5-1.

Drawing on these analogs to inform growth rate and cost predictions, Edwards et al. (2024) find that while methane emissions mitigation generally would be less expensive than atmospheric methane removal, removal could become cost-competitive with some mitigation technologies if costs reach levels competitive with those of CDR technologies. Hickey and Allen (2024) estimate that enhanced oxidation techniques are not cost-competitive with CDR for contributions to long-term levels of warming, but photocatalytic methods could be cost-competitive with CDR when valuing the immediate rate of warming (with biofiltration, thermal-catalytic oxidation, and capture-based approaches remaining uncompetitive).

Edwards et al. (2024) also note that even if atmospheric methane removal technologies do not ultimately compare favorably to other options on an average cost basis, they may be beneficial for some applications—for example, areas of enhanced methane concentrations where emissions mitigation technologies may not be available. Additionally, companies or individuals may wish to offset their GHG emissions by gas, removing a unit of methane for each unit of methane they emit rather than substituting CDR for methane emissions.

Cost decreases for atmospheric methane removal technologies can come from technical improvements—for example, solar updraft towers or air preheating loops via flue gases (Tong et al., 2018) or heat pumps (Pimm et al., 2023) for thermocatalytic processes. Synergistic coupling of atmospheric methane removal technologies with other operations, and/or the valuation of co-benefits, could also provide needed economic support for the further development of these technologies (see Chapter 4).

Conclusion 5.9: Cost estimates for all atmospheric methane removal technologies are highly preliminary given how early the technologies are in their development.

Conclusion 5.10: Atmospheric methane removal technologies could plausibly be cost-competitive with some methane emissions mitigation approaches if the atmospheric methane removal cost levels and growth rates reach those seen by analogous technologies, such as carbon dioxide removal (which are in early stages of commercial-scale demonstration). Importantly, methane emissions mitigation is still the most cost-effective means of addressing the growing concentrations of atmospheric methane.

TABLE 5-1 Analogs for Atmospheric Methane Removal Technologies, Employing the Systematic Historical Analogue Research for Decision-Making Approach

| Methane Removal System Type | Methane Removal Technology | Cost Target Analogs | Leverage Point and/or Growth Rate Analogs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Closed Systems | Methane concentrators and methane reactors | Carbon dioxide (CO2) removal method: direct air carbon capture and storage (DACCS) “Conventional” methane mitigation |

Early experience with DACCS Other advanced processes that convert components of ambient air (e.g., ammonia synthesis) Renewable energy technologies (given large energy input requirements) Air separation processes and technologies that share similar components such as gas-to-liquid technologies |