A Research Agenda Toward Atmospheric Methane Removal (2024)

Chapter: 6 Research Agenda

6

Research Agenda

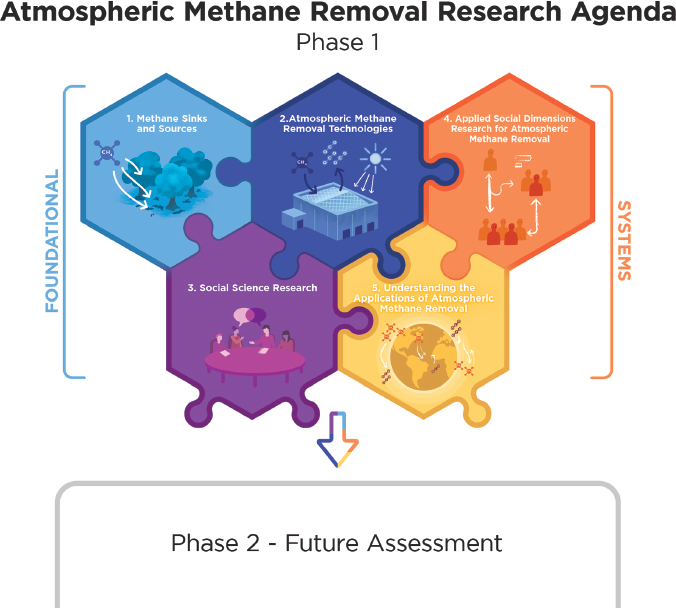

The Committee recognizes that atmospheric methane removal is an emerging area of research and has assessed the currently available information across sociotechnical dimensions in Chapters 4 and 5 of this report. However, for the task of fully assessing the need and potential for atmospheric methane removal, the Committee recommends a two-phase approach. In this first-phase report, the Committee has identified priority research questions that should be addressed within 3–5 years (see Figure 6-1). With the results from this research, a second-phase assessment could more robustly assess the viability of technologies to remove atmospheric methane at 2 parts per million (ppm)—from the perspective of both technical, economic, and broader social viability and the potential for climate-scale impacts. Advances in the recommended research areas and a second-phase assessment would inform any decision to move from knowledge discovery into more targeted investment in additional research, development, and/or deployment as well as help identify possible off-ramps for technologies that did not meet criteria based on performance and/or acceptability. It is beyond this Committee’s purview to specify the mechanism, process, or outcomes of any future phase-two assessment.

The utility of a sequence of reports evaluating the progress of emerging technologies has been demonstrated in the past—for example, carbon dioxide removal (CDR) was assessed in NRC (2015a) and again in NASEM (2019b); solar geoengineering was assessed first in NRC (2015b) and subsequently in NASEM (2021b). Smith et al. (2023, 2024) published the first and second reports establishing a series toward a comprehensive scientific assessment of the state of CDR. Pett-Ridge et al. (2023) outlined options for CDR across the United States, building on the body of literature and developing original analysis. As an example from another area of emerging climate technology, the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) assessed the potential for terawattscale photovoltaics initially (Haegel et al., 2017) and on a global scale (Haegel et al.,

2019). NREL has also produced a series of technical reports in collaboration with the International Energy Agency on the life-cycle assessment of photovoltaics (Frischknecht et al., 2020; Heath et al., 2015; Stolz et al., 2018). In these examples, earlier reports assessed the knowledge base and recommended research to advance understanding, and subsequent reports used research progress to provide recommendations about technology development, deployment, and guardrails. The Committee recognizes the value of moving research forward in the near term to inform understanding of atmospheric methane removal and assess the potential impact of this important emerging concept to inform decision making.

Recommendation 6.1: A two-phase assessment of the need and potential for atmospheric methane removal is needed.

- This report represents phase one, in which the Committee has developed recommendations for priority foundational and systems research across five areas that should be initiated in parallel within 1 year of publication.

- The research in phase one should be completed or significantly advanced to inform a phase-two assessment within 3–5 years of this report.

- In both phases, the research areas should be transdisciplinary and pursued as convergence research with deep disciplinary integration among research teams in early stages of inquiry to maximize learning across diverse fields.

The research agenda recommended in this chapter is organized into foundational and systems research needs. The foundational research questions seek to fill knowledge gaps in basic understanding of atmospheric and ecosystem methane sinks, atmospheric methane removal technologies (e.g., technical feasibility between 2 ppm and 1,000 ppm), and social dimensions of how publics and society would interact with research on atmospheric methane removal. The recommended foundational research not only would advance understanding of atmospheric methane removal but also would constitute an investment in filling knowledge gaps in other related fields, representing a cost-effective use of limited resources for research. The systems research questions seek to address what developing and/or deploying atmospheric methane removal at scale would entail from technological (e.g., inputs needed to achieve climate-scale removal per year) and social perspectives. The Committee has sought to distinguish between research questions that would be most useful to answer before a second-phase assessment (“high priority”) and those that may take longer but where progress would provide a valuable contribution to the phase-two assessment (“low to medium priority”). This prioritization of research questions does not imply an evaluation of potential impact of the research but reflects the current knowledge gaps that need to be addressed to enable a phase-two assessment.

Within the broad categories of foundational and systems research, the Committee has identified five research areas around which the recommended research questions are organized:

- Research Area 1: Methane Sinks and Sources

- Research Area 2: Atmospheric Methane Removal Technologies

- Research Area 3: Social Science Research

- Research Area 4: Applied Social Dimensions Research for Atmospheric Methane Removal

- Research Area 5: Understanding the Applications of Atmospheric Methane Removal.

The total number of research questions among Research Areas 1, 3, 4, and 5 are comparable, whereas Research Area 2 has the largest number of research questions, given the focus of this report.

To advance knowledge across the full range of sociotechnical dimensions that are relevant to informing a phase-two assessment, these prioritized foundational and systems research questions should be pursued in parallel. Furthermore, many of the foundational and systems research questions have interdependencies (as illustrated in Figure 6-1). For example, developing life-cycle and economic models (Research Area 5) will require inputs on the materials and reaction rates of the specific atmo-

spheric methane removal technologies (Research Area 2). Similarly, social perception and governance questions (Research Areas 3 and 4) would be informed by increasing the state of knowledge of existing atmospheric and ecosystem methane sinks (Research Area 1) and atmospheric methane removal technologies (Research Area 2).

In both phases, the recommended research areas should be integrative and transdisciplinary. By integrative, the Committee means research in which knowledge from different disciplines is integrative, perhaps evolving into a shared set of methods and concepts that comes to be used by collaborators. “Transdisciplinary” can refer to interaction between disciplines in defining the research but often includes other features: research that is socially engaged, reflexive, and focuses on real-world problems (Lawrence et al., 2022). Atmospheric methane removal falls into the broad categories of “wicked problems” or “grand challenges” within sustainability science—complex socioecological problems that demand working beyond disciplinary silos (Sundstrom et al., 2023). While convergent research lacks one standard definition, it is focused on deep integration of knowledge across disciplines to address socially relevant problems and create new fundamental knowledge; themes include addressing social justice, integrating team science, and requiring diverse teams (Thompson et al., 2023). The Committee recommends that research on atmospheric methane removal be funded through a convergent approach to maximize learning between social and biophysical sciences, for example, and ensure that the outputs of the research do not remain siloed but are used and integrated by people from diverse fields. Within the recommended research areas, not all individual research questions would require a transdisciplinary, convergent approach. This recommended approach would cohere with other research efforts funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF), such as the Convergence Accelerator1 or the Growing Convergence Research Program,2 or efforts funded through NSF’s Office of Integrative Activities.3

Each research area includes a description of the context motivating the specific research questions identified by the Committee as well as a description of the priority for informing a second-phase assessment, research program length, total cost (categorized as low [$5 million], medium [$20 million], or high [$50 million]), and potential funders. The research agenda is summarized in Table 6-2 at the end of this chapter. The Committee focused on public sector funding opportunities at U.S. federal agencies and identified opportunities for philanthropic and private research funding, as appropriate. Potential funders described in this chapter are meant to serve only as illustrative examples and should not preclude investments from those not listed (e.g., public sectors outside the United States). The final section of this chapter synthesizes the Committee’s recommendations and looks ahead to a phase-two assessment.

The Committee suggests that a reasonable initial investment in basic science that would help society understand the prospects of atmospheric methane removal is in the range of $50 million–80 million per year over 3–5 years. A research program of

___________________

1 See https://new.nsf.gov/funding/initiatives/convergence-accelerator.

2 See https://new.nsf.gov/od/oia/ia/growing-convergence-research-nsf.

this size would advance the five research areas recommended to inform a phase-two assessment, as outlined in Recommendation 6.1. The Committee emphasizes that any investment in the foundational research areas identified in this research agenda would also represent research investments to fill knowledge gaps in related disciplines (see Table 6-2), independent of progress toward atmospheric methane removal.

FOUNDATIONAL RESEARCH NEEDS

Previous chapters in this report outlined knowledge gaps across a wide range of areas that inhibit current understanding of the technical capabilities and physical and social implications of atmospheric methane removal. These gaps point to the need for foundational research on methane sinks; the technical potential of different atmospheric methane removal technologies; and the social dimensions across which people, social, and political systems may interact with these technologies. Foundational research also has synergies with other research fields such that investments in research motivated by atmospheric methane removal would be valuable investments toward informing unanswered questions in a wide range of other fields of study, from chemical engineering to microbiology to social science. Examples of these synergies are provided below and in Table 6-2. In this section, foundational research questions are identified across three themes: methane sinks and sources (Research Area 1); atmospheric methane removal technologies (Research Area 2); and social science research (Research Area 3).

Research Area 1: Methane Sinks and Sources

Atmospheric methane removal seeks to accelerate conversion of methane in the atmosphere to a less radiatively potent form, including through technologies that would enhance natural methane sinks in the atmosphere and managed ecosystems. Research is needed on these atmospheric and ecosystem methane sinks to reduce uncertainties in natural processes, improve understanding of the potential to enhance these sinks for atmospheric methane removal (see also Research Area 2), and inform estimates of the scale of atmospheric methane removal technology deployment required for climate-scale impacts (see also Research Area 5). Additionally, research to improve understanding of methane sources—particularly natural sources—would inform potential applications of atmospheric methane removal technologies (see also Research Area 5) and the potential consequences of these technologies on the lifetime and concentrations of atmospheric methane. Research to reduce uncertainties in the methane budget would also enable the monitoring, reporting, and verification (MRV) of atmospheric methane removal technologies (see also Research Areas 2 and 5).

Investments in the research questions identified in this area would also be valuable toward knowledge discovery in other fields of research including methane cycling; MRV of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and removals; biology; and atmospheric chemistry. In the sections that follow, this research area has been organized into research questions on atmospheric methane sinks, methane sinks in managed ecosystems, natural methane sources, and anthropogenic methane sources. Of the sub-areas outlined below,

advancing foundational research on methane sinks is the highest priority to inform any phase-two assessment.

Atmospheric Methane Sinks

The main atmospheric sink of methane (CH4) is oxidation by the hydroxyl radical (OH) (~90% of the total sink). Understanding of the oxidative capacity of the troposphere by OH is critical for understanding the potential for and consequences of any atmospheric methane removal technology. Current understanding of oxidative capacity has been inferred from measurements of methyl chloroform; however, as methyl chloroform concentrations have approached detection limits over the past decade, uncertainty in the oxidizing capacity of the troposphere has increased (see Chapters 2 and 3). New methods of monitoring the oxidative capacity of the atmosphere are needed to improve understanding of methane sinks, drivers of future methane trends, and the scale of atmospheric methane removal that would be needed for a climate-scale impact. New observational methods would also help to fill observational gaps in the chlorine (Cl) sink for methane (e.g., Röckmann et al., 2024).

Importantly, atmospheric oxidation enhancement (AOE) approaches that require large additions of chlorine or hydrogen peroxide to the atmosphere (see Chapter 4) would significantly affect the oxidative capacity of the atmosphere and atmospheric photochemistry. For example, large additions of chlorine to the atmosphere would compete with OH for reaction with methane, which would have nonlinear and cascading impacts for many organic and inorganic species in the atmosphere. Monitoring changes to the oxidative capacity of the atmosphere would be critical to understand the atmospheric impacts of any atmospheric methane removal technology, AOE in particular. Furthermore, better understanding of the oxidative capacity of the atmosphere would advance understanding of tropospheric chemistry more broadly, including for consequences of changes to the global energy system and other climate response strategies (Research Area 5). For the reasons described above, the research recommended in this sub-area is of high priority to inform a phase-two assessment.

Previous work has identified three promising directions for monitoring changes in the oxidative capacity of the troposphere and the methane sink. First, carbon-14-containing carbon monoxide (14CO) has been long-recognized as a useful tracer for OH (e.g., Brenninkmeijer et al., 1992). Briefly, 14C is formed in the stratosphere by cosmic rays and rapidly oxidized to form 14CO. This 14CO is then transported to the troposphere where it can be oxidized by OH. As such, the amount of 14CO that ultimately reaches the surface will be inversely related to the oxidizing capacity of the troposphere. This measurement is difficult and previously required very large air volumes. Recent advances have made this measurement more feasible (e.g., Petrenko et al., 2021).

Second, isotopic measurements could constrain the chlorine sink of methane (e.g., Röckmann et al., 2024). The oxidation of methane produces CO as an intermediate product. The chlorine sink of methane (CH4 + Cl) imparts a strong signal on 13CH4, whereas the OH sink of methane does not. As such, measurements of the ratio of 13C to 12C in CO (δ13C-CO) are indicative of changes in the chlorine sink of methane. The feasibility

of these measurements was demonstrated many years ago (Brenninkmeijer, 1993), but routine observations of δ13C-CO are not currently collected. Routine δ13C-CO measurements would illuminate the impact of halogens on the methane lifetime (Röckmann et al., 2024), which would be highly relevant to understanding AOE (Research Area 2).

Third, previous work (e.g., Holmes et al., 2013; Murray et al., 2014; Turner et al., 2018) has demonstrated that the oxidizing capacity of the troposphere generally will depend on the ozone photolysis frequency, specific humidity, sources of reactive nitrogen (i.e., nitrogen oxides [NOx]), and sources of reactive carbon (e.g., methane and volatile organic compounds) (see Chapter 2). Many of these species are observed from satellite observations. As such, recent work has developed preliminary satellite proxies of the oxidative capacity of the troposphere using pre-existing satellite observations (e.g., Anderson et al., 2023; Duncan et al., 2024; Souri et al., 2024; Zhu et al., 2022). These satellite proxies would provide spatial coverage that would complement the isotopologue measurements described above. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), other international space agencies, and private companies operating and/or developing satellite observations could inform these efforts.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) currently operates a cooperative air sampling network in collaboration with international partners (NASEM, 2022c). The Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research (INSTAAR) at the University of Colorado Boulder currently analyzes NOAA’s air samples for the stable isotopes of carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane. Research Questions 1.1a and 1.1b should be carried out either by or in collaboration with NOAA and INSTAAR to expand their operational monitoring capacity. Support for this research would involve upfront instrument and personnel costs and would require sustained funding support to build a continuous measurement record, with a total program cost of $5 million–20 million. Additional research on the capabilities of satellite observations to constrain the oxidative capacity of the atmosphere (Research Question 1.1c) could be supported by NASA and/or private funders. The Committee recommends a research program that is carried out over 10 years, with interim progress assessed.

Research Question 1.1: How can changes in the oxidative capacity of the troposphere and lifetime of methane be monitored?

- How can an observational network that measures carbon-14-containing carbon monoxide in ambient air provide estimates of the oxidative capacity of the troposphere?

- How can an observational network that measures the ratio of 13C to 12C in carbon monoxide in ambient air provide estimates of changes in the chlorine sink of methane?

- How can satellite observations provide operational estimates of spatial variability in hydroxyl radicals?

- What is the potential (and limitation) for each of these methods to enable monitoring of the atmospheric oxidation enhancement technologies both locally and globally, described in Research Area 2?

Methane Sinks in Managed Ecosystems

Methanotrophs in soils, aquatic systems, and foliar systems are natural methane sinks that could be enhanced to remove atmospheric methane (see Chapter 4). Methanotroph activity can be enhanced by increasing the quantity or distribution of efficient microbial types, enhancing nutrient conditions to facilitate their activities, or providing more surfaces for naturally emerging populations; these activities will vary by system type and biogeochemical constraints. Basic gaps in the understanding of the factors controlling methanotrophy in different global ecosystems remain. Advances in this foundational research area would improve understanding of the potential and efficacy of ecosystem uptake enhancement (Research Area 2).

In any soil environment, the most influential soil properties that alter methane uptake are related to the rate of gas diffusion into soils (e.g., water-filled pore space, bulk density, temperature) and to the biogeochemical factors that affect the activity of methanotrophs and methanogens (e.g., soil carbon, nutrient status, pH, plant populations, temperature). Soil systems are complex; accurate modeling of methane uptake by methanotrophs depends on understanding the biology of microbes in situ as well as nutrient cycling from different management practices and landscape alterations from climate change impacts. Understanding the conditions under which different soil systems can enhance methane uptake would inform the development of atmospheric methane removal technologies that could enhance these natural processes. Research questions in this area are complementary to questions on ecosystem uptake enhancement in Research Area 2.

Research Question 1.2 could be explored over 10 years for $5 million–20 million. Federal agencies, including the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), U.S. Geological Survey, NSF, U.S. Department of Energy (U.S. DOE), and U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) would be well suited to fund this research. The fundamental research on methanotrophy (foliar, soils, others) could lead to new management approaches in environments providing key ecosystem services (e.g., grasslands, forests, wetlands, arid or semi-arid regions), including to enhance the methane sink. Research in this area would also represent an investment in knowledge gaps in the carbon cycle, agronomy and soil science, forestry, biology, microbiology, and ecology by improving understanding of methanogens/methanotrophs in ecosystems and how they respond to a variety of environmental/climatic conditions. This research is of high priority for any phase-two assessment because understanding ecosystem sinks would inform both the climate relevance of managing these sinks—for example, water sources (as watersheds are channeled or dams constructed), geochemical inputs by erosion or transport, conservation of areas prone to effective removal or exclusion of activities that lower methanotrophy—as well as the natural processes relevant to the potential of ecosystem uptake enhancement (Research Area 2).

Research Question 1.2: Under what conditions do methanotrophs maximize their uptake of atmospheric methane in different environments?

- Under what in situ conditions do novel and known methanotrophic taxa reach their highest activity in terrestrial (managed and unmanaged soils), aquatic, and foliar environments, and what are their key biogeochemical constraints?

- What are the functional limits (e.g., conditions, nutrients, and metabolic competition) of methanotrophic taxa operating at or near atmospheric methane concentration levels in cultures and in diverse ecosystems (~2 parts per million)?

- What factors determine which plants favor higher rates of methanotrophy (and thus methane removal) while others do not?

- What factors limit foliar methanotrophy (e.g., biomass, solar radiation stress, nutrient limitation)?

Terrestrial soils are an important ecosystem methane sink (~5% of the total global methane sink; see Chapter 2) (Saunois et al., 2024). While soils under frequent water-saturated conditions can represent sources of methane, these environments also contain methanotrophic microbes that can consume methane at near-atmospheric levels (Cai et al., 2016; Conrad & Rothfuss, 1991; Frenzel et al., 1992; Tveit et al., 2019). Atmospheric methane oxidation has been detected in wetland soils during dry seasons or intense droughts, though the magnitude of this sink is uncertain. While well-drained soils may serve as consistent sinks for atmospheric methane (including upland permafrost soils), the rates of natural atmospheric methane removal activity are affected by various processes, including seasonal variation in pristine lands, land use change, and management practices of converted lands (particularly agricultural and grazing lands). Better understanding of methane fluxes from soils is needed to consider both the process and impacts of enhancing natural removal processes via ecosystem uptake enhancement.

Managed systems are potentially attractive ecosystems for enhancing atmospheric methane removal because they are sites where humans already interact with the landscape. Agricultural soils, which represent a large land area globally, represent one managed ecosystem where enhanced methane removal could be considered. More broadly, anthropogenic land use changes can impact the methane fluxes of ecosystems due to land conversion or other anthropogenic interventions. Research needs in both areas are described below. The Committee estimates that Research Question 1.3 could be explored over 10 years for $5 million–20 million. Government agencies (e.g., USDA, NSF, USAID) as well private funders (e.g., philanthropies promoting agricultural, reforestation, or carbon market developments) would be well suited to fund this work. This research is also of high priority for any phase-two assessment for the reasons described above.

Key uncertainties limiting understanding of the methane sink in agricultural soils include the maximum rate of methane consumption across different croplands, the spatiotemporal variation of soil methane consumption for most crops and regions based on localized biogeochemical constraints, and variations in removal effects due to different land management or land use strategies. Research into the development of cropping and grazing systems with enhanced methane uptake would provide valuable information about the mechanisms that affect methane uptake and would provide tools for producers to select systems or practices that would enhance atmospheric methane removal. Cropping systems utilizing reduced/deficit irrigation, crop residues to enhance soil carbon, alternate fertilizer management (including source, rate, and placement), soil amendments that alter pH, crop rotations, and other management strategies could be

investigated to develop optimal systems for atmospheric methane removal and improve overall soil health. Grazing systems utilizing rotational grazing, fertilization, and soil amendments could improve overall soil heath, productivity, and carbon sequestration as well as enhance atmospheric methane removal. Research could be conducted at the plot to landscape scale to assess treatment or management strategies and capture interactions within the environment.

USDA would be well suited to fund relatively low-cost research that would analyze existing data from the GRACEnet (Greenhouse Gas Reduction through Agricultural Carbon Enhancement Network) program on methane fluxes in soils from a wide range of climatic regions, soil types, cropping systems, and management (tillage, irrigation, etc.) to evaluate the potential methane sink of U.S. agricultural soils and identify practices that may enhance this sink. Additionally, the National Strategy to Advance an Integrated U.S. Greenhouse Gas Measurement, Monitoring, and Information System (GHGMMIS) recommends that USDA establish the national Soil Organic Carbon Monitoring and Research Network, which would monitor soil carbon changes over time across agricultural systems (The White House, 2023b). The recommended research would complement this new network by providing data related to carbon cycling in a variety of agricultural systems and improving estimates of methane fluxes.

Additionally, the biological methane cycle is highly sensitive to land use and natural landscape changes that promote warm, wet, carbon-rich environments that stimulate methane production over methane consumption. Across terrestrial ecosystems, undisturbed forests, grasslands, and shrublands have been shown to remove methane at the highest rates (Chen et al., 2011; Singh & Gupta, 2016). Atmospheric methane removal rates are adversely affected by anthropogenic activities (e.g., forest harvesting, roads and transiting, mining, burning, and urbanization) that reduce soil structure and quality. Reforestation and afforestation are common ecosystem restoration approaches that have been proposed and documented to increase soil methane consumption (Hemes et al., 2018; Hiltbrunner et al., 2012; Nazaries et al., 2011; Wu et al., 2018); however, land restoration efforts may not improve methanotrophic activity in soils to the extent of nondegraded sites (J. Wu et al., 2020). Research is needed to improve understanding of how and in what direction landscape-scale changes impact methane fluxes, how interrelated cycles (e.g., N-cycle, atmospheric oxidants) further alter the accumulation and persistence of atmospheric methane, and what the limitations are to recovering or enhancing soil methanotrophy in restored ecosystems.

Research Question 1.3: How are ecosystem methane sinks impacted by amendments and/or management practices?

- Which ecosystems are increasing capacity as methane sinks, and which are losing capacity?

- What are the rate and biogeochemical constraints of atmospheric methane consumption in environments with the potential for methane removal enhancements including wetlands, rice paddies or other wet soils during dry periods, grazing lands, drylands, Yedoma soils, floating vegetation, leaves, and tree stem surfaces?

- How do management factors (e.g., soil tillage, irrigation, fertilization regime, ecosystem amendment) influence the rate of methanotrophy in situ, and can these factors be optimized and directed toward atmospheric uptake?

- What is the capacity of agricultural soils to serve as a sink for atmospheric methane? What soil conditions, biogeochemical factors, climatic conditions, and management practices (e.g., tillage, irrigation, fertilization, grazing strategies) stimulate or decrease methanogen and methanotroph activities?

- What impacts do land use changes in managed (e.g., agricultural, reservoirs, forests) systems have on methane fluxes from ecosystems?

Natural Methane Sources

The Global Carbon Project publishes a living review every 4 years synthesizing decadal estimates of the methane budget based on ensembles of bottom-up and top-down approaches (Kirschke et al., 2013; Saunois et al., 2016, 2020, 2024). These budgets also outline key research needs that would improve future budgets. The Committee seeks to build on, rather than reproduce, these existing efforts, and it highlights in this and the following research sub-area specific questions that would inform potential applications of atmospheric methane removal technologies and understanding of the scales of atmospheric methane removal needed for climate-scale impacts.

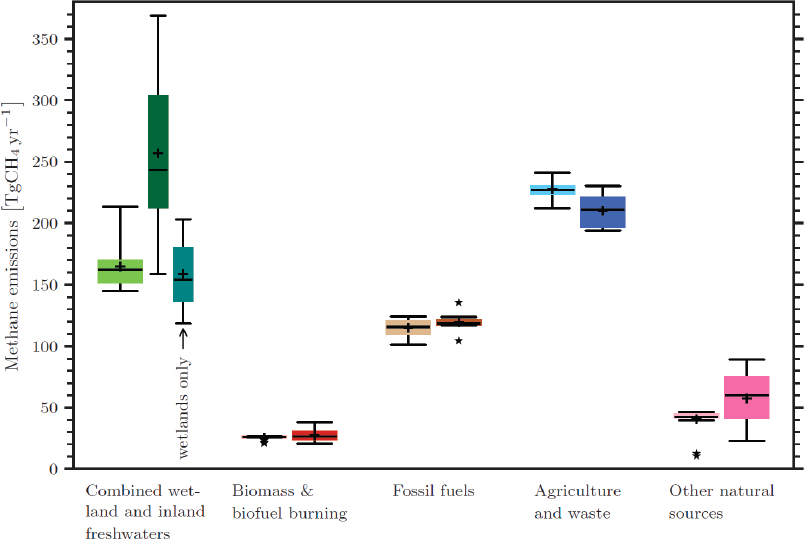

Figure 6-2 shows estimates of global methane emissions for 2010–2019 from Saunois et al. (2024). There are large uncertainties in natural methane sources where historically less attention has been dedicated to source-level monitoring—in part due to their high spatiotemporal variability—and these sources are sensitive to the impacts of climate change (see Chapters 2 and 3). New research in the global methane budget (Saunois et al., 2024) also estimates the role of natural and indirect anthropogenic methane emissions associated with wetlands and inland freshwater systems, including ~30 teragrams (Tg) CH4 yr-1 emitted by reservoirs (Jackson et al., 2024). Changes in natural methane sources could counteract reductions in anthropogenic emissions and contribute to a potential “methane emissions gap” (see Chapter 3), and approaches to mitigate these emissions are not currently available. To understand the potential need for applications of atmospheric methane removal technologies, research is needed to reduce uncertainties in current and projected changes in global methane emissions from wetlands and lakes, natural geologic sources, and permafrost soils and thermokarst.

Wetlands are the largest source of natural methane emissions, accounting for 159 (119–203) Tg CH4 yr-1 or ~50 percent of natural and ~24 percent of total global methane emissions, and lakes are the second largest source of natural methane emissions (53 [19–86] Tg CH4 yr-1) (Saunois et al., 2024). The latest global methane budget summarized recent advances to reduce uncertainties in emissions from wetland and inland freshwater systems (Saunois et al., 2024); however, these sources remain the most uncertain components of the global methane budget (see Figure 6-2). Research is needed to improve observations and models of current emissions from wetlands and projections of the climate feedbacks on emissions from wetlands and lakes, particularly in light of the fact that current climate response policies do not account for the potentially

SOURCE: Saunois et al. (2024).

increasing role of methane emissions from wetlands (Zhang et al., 2017). Synergies may exist between understanding these climate-methane feedbacks and climate-carbon cycle feedbacks more broadly, as well as the emissions mitigation or removals required to offset such anticipated feedbacks.

Some studies attribute increases in atmospheric methane concentration since 2007 to rising microbial emissions (Oh et al., 2022) linked to positive climate feedbacks on tropical, sub-tropical, and northern wetland emissions (L. Feng et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2023); however, large uncertainties remain in the attribution of methane trends over this time period (e.g., Turner et al., 2017, 2019), indicating a need for more research. There are large regional differences in the methane isotopic source signatures from these aquatic ecosystems (Brosius et al., 2012; Ganesan et al., 2018; Haghnegahdar et al., 2023; Walter Anthony et al., 2016). Improved monitoring of stable methane isotopes and source signatures could help track sources, changes in methane emissions, and

improve model estimates. A suite of measurements—including eddy covariance, tall towers, aircraft, drones, and satellites—could improve understanding of the magnitude and patterns of methane fluxes. Research could be conducted at the field/landscape scale over at least 5 years to understand fluxes in methane emissions from wetlands and lakes.

Natural geologic methane emissions are one of the most uncertain terms in the global methane budget (Etiope & Schwietzke, 2019). Bottom-up approaches attribute 45 (18–63) Tg CH4 yr-1 to natural geologic sources (Saunois et al., 2024), while top-down constraints from measurements of 14C-CH4 in ancient air trapped in polar ice cores suggest that the geological methane source is an order of magnitude smaller (Dyonisius et al., 2020; Hmiel et al., 2020; Petrenko et al., 2017). These sources have been comprehensively mapped outside the Arctic, with diffusive microseepage fluxes dominating emissions (24 Tg CH4 yr-1) (Etiope et al., 2019), albeit with high uncertainties due to a paucity of flux data covering the wide range of hydrocarbon basin characteristics worldwide. Far less is known about natural geologic methane emissions in the Arctic and Antarctic, yet permafrost and ice sheets are thought to cap vast pools of methane that will be more vulnerable to escape as the cryosphere degrades due to climate change (Kleber et al., 2023; Sullivan et al., 2021; Wadham et al., 2019; Walter Anthony et al., 2012). An opportunity exists to use fieldwork and remote sensing tools to better quantify natural geologic methane emissions in polar and non-polar emissions and their responses to a changing climate.

Direct emissions from permafrost soils are currently small contributors to the global methane budget (1 [0–1] Tg CH4 yr-1), though current wetland and freshwater methane emissions already likely include an indirect contribution from thawing permafrost (Saunois et al., 2024). Natural methane emissions estimates can also be uncertain as many models assume homogeneity in tundra landscapes and fail to account for natural fluxes in net ecosystem exchange where CO2 and methane are regularly in flux (Ludwig et al., 2024). While currently a small natural methane source, ice-rich permafrost soils, known as Yedoma and formed during the last Ice Age, harbor a large pool of frozen soil organic carbon (~450 billion tons) (Hugelius et al., 2014, 2020). The formation of thermokarst (thaw) lakes is currently the most widespread form of permafrost thaw leading to mobilization of this ancient permafrost carbon and its transformation by microbes in anaerobic lake bottoms. Yedoma thermokarst lakes have the highest methane emissions among all permafrost-region ecosystems (Delwiche et al., 2021; Treat et al., 2018; Walter Anthony et al., 2018, 2021); however, new evidence suggests talik (thaw bulb [perennially unfrozen soil layers in permafrost regions]) formation in well-drained permafrost uplands leads to unexpectedly high methane emissions (Walter Anthony et al., 2024), with large implications for permafrost-climate feedback modeling.

These lakes and Yedoma uplands also host highly active methanotrophic bacteria that consume methane dissolved in lake water (Martinez-Cruz et al., 2015) and aerobic surface soils (Walter Anthony et al., 2024). Nonetheless, preferential-flow pathways in thawed sediments allow methane to escape to the atmosphere, bypassing oxidation in both systems. Development of novel remote sensing approaches (Engram et al., 2020) provides an opportunity to identify lakes with the highest methane emissions to target research related to methane mitigation and atmospheric methane removal. New

ground-based and airborne methods of methane hotspot imaging on land (Elder et al., 2021; Gålfalk et al., 2016) could be useful for identifying upland-talik methane hotspot locations as targets for methane mitigation and/or atmospheric methane removal.

Research in this sub-area is a medium priority (after atmospheric and ecosystem sinks) for any phase-two assessment because better understanding natural methane sources and climate feedbacks would help quantify the potential “methane emissions gap” and the scale of atmospheric methane removal that may be needed. This research would also advance knowledge in other fields of research on the carbon cycle, GHG observing systems, paleoclimate, and climate modeling. The Committee estimates that Research Question 1.4 could be explored over 5–10 years for at least $20 million–50 million. This research could be funded by a variety of federal agencies (e.g., U.S. DOE, NASA, National Institute of Standards and Technology [NIST], NOAA, NSF) as well private funders and industry.

Research Question 1.4: What is the magnitude and variation of methane emissions from natural sources (wetlands and lakes, natural geologic sources, permafrost soils and thermokarst), and how are these emissions projected to change under future warming scenarios?

- How can observational (fieldwork and remote sensing) tools be used to quantify methane emissions from natural sources more accurately, including better characterization of seasonal and episodic fluxes?

- How are natural emissions changing in response to current warming? How can models used for future emissions projections be improved to include climate feedbacks on natural methane fluxes?

- Are there regions of high-concentration natural emissions that could be addressed with methane mitigation or atmospheric methane removal technologies?

Anthropogenic Methane Sources

Relative to the other components of the methane budget, anthropogenic methane sources are well characterized (see Figure 6-2). Unlike global anthropogenic emissions of CO2, which are dominated by large industrial sources, anthropogenic methane emissions come mostly from smaller distributed point sources, and emissions occur at diffuse concentrations below the limit (~1,000 ppm) of currently available methane oxidation technologies (see Chapters 2 and 3).

Research funding in the public and private sectors has supported advances in observing systems for large methane point sources and data and modeling tools that have improved estimates of methane emissions from the major anthropogenic sources: fossil fuels, agriculture, and waste (see Chapter 2). In addition, regulatory requirements—for example, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Greenhouse Gas Reporting Program (GHGRP)—have improved data availability (see Chapter 2). Given robust existing efforts in this space, the section below identifies targeted research needs related to current knowledge gaps in anthropogenic methane sources that are hard-to-abate because they are diffuse and/or have limited or no mitigation options available

(see Chapter 2), making them relevant to research on atmospheric methane removal. Additionally, monitoring tools utilized or developed to support this research could inform the development of MRV tools for atmospheric methane removal technologies (Research Question 1.6). For the reasons stated above, this sub-area is the lowest priority from Research Area 1 for a phase-two assessment.

Methane emissions from agriculture represent 40 percent of total anthropogenic emissions (143 [132–155] Tg CH4 yr-1, with 112 [107–118] Tg CH4 yr-1 from enteric fermentation and manure and 32 [25–37] Tg CH4 yr-1 from rice cultivation) (Saunois et al., 2024). Emissions from both enteric fermentation and rice paddies are typically diffuse where production systems tend to be most extensive. Accurate determination of ruminant enteric emissions and development of mitigation strategies in extensive production systems remain a challenge. In addition, in confined livestock production systems, manure management can become a significant source of on-farm methane emissions when manure is stored as a liquid where anaerobic conditions are maintained, generating hot spots of methane emissions. Improving methane emissions estimates from manure storage would enable more accurate reporting and improve quantification of potential reductions from the application of methane mitigation or atmospheric methane removal technologies. Research recommended below on hard-to-abate agricultural sources would complement strategic objectives identified elsewhere (e.g., PCAST, 2024; The White House, 2023b) and resources already allocated (e.g., $70 million to USDA’s Agricultural Research Service from the Inflation Reduction Act).

The Committee estimates that Research Question 1.5a could be explored over 5–10 years for at least $50 million. In addition to USDA, private industry would be well suited to contribute funding for this research. This research could be useful to inform the phase-two assessment because it would improve understanding of baseline emissions and inform whether targeted atmospheric methane removal or improved mitigation technologies could be applicable to these sectors. However, the scale and length of research may limit the data available in 3–5 years.

Emissions from coal mines and landfills account for large sources of methane in the United States and globally, and Chapter 3 introduced the state of recovery and use of concentrated methane from these sources. Coal mine ventilation of relatively dilute (<1,000 ppm) methane presents a potential opportunity to oxidize and/or utilize this methane should technologies that operate at lower methane concentrations be developed (Research Area 2); however, the magnitude and temporal variation of these emissions could be better constrained. Improved understanding of coal mine ventilation emissions could make a more compelling case to mine operators and developers regarding the potential for methane conversion projects. This research would also inform Research Area 5, which considers optimal systems for demonstration or deployment of atmospheric methane removal technologies. The GHGMMIS recommends the formation of a Coal Mine Emissions Working Group to coordinate federal efforts to improve emissions estimates, particularly to reconcile atmospheric- and activity-based estimates of emissions from active underground coal mines (The White House, 2023b), which would be complementary to Research Question 1.5b.

Municipal solid waste landfills account for the largest source of methane emissions in the waste sector in the United States (U.S. EPA, n.d.d). Emissions of landfill

gas vary depending on site-based operational conditions, which may not be well represented in emissions estimates. Recent remote sensing observations of 20 percent of U.S. landfills found significant and persistent methane emissions and found large discrepancies between estimates from the GHGRP and airborne observations (Cusworth et al., 2024). Improved estimates of landfill methane emissions could similarly inform mitigation opportunities as well as lessons learned for the development of atmospheric methane removal technologies that could operate at lower methane concentrations than those at landfills. Complementary to Research Question 1.5c, the GHGMMIS also recommends improving emissions estimates from landfills using activity- and atmospheric-based approaches and developing cost-effective measurement and monitoring approaches. U.S. EPA currently is funding $4.6 million in research grants for developing cost-effective approaches for quantifying landfill emissions using different types of measurements.4

The Committee estimates that Research Questions 1.5b and 1.5c could be explored over 5–10 years for $20 million. Potential funders of this research could include the U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. EPA, NASA, NOAA, NIST, and private industry.

Research Question 1.5: How much hard-to-abate methane is emitted globally at concentrations above and below those that can be oxidized using available technologies (i.e., ~1,000 parts per million)? What are the opportunities for the application of mitigation or atmospheric methane removal technologies to these sources?

- For hard-to-abate agricultural sources (e.g., extensive livestock systems, manure management, leaks from digesters and advanced treatment systems, paddy rice systems), what are the concentrations, volume, and mass flow rates of methane, and how consistent are they through time? What available methane mitigation or atmospheric methane removal technologies could be applied to these sources?

- For hard-to-abate fossil fuel sources (e.g., operating and abandoned coal mines), what are the concentrations, volume, and mass flow rates of methane, and how consistent are they through time? What available methane mitigation or atmospheric methane removal technologies could be applied to these sources?

- For hard-to-abate waste sources (e.g., municipal solid waste landfills and water treatment facilities), what are the concentrations, volume, and mass flow rates of methane, and how consistent are they through time? What available methane mitigation or atmospheric methane removal technologies could be applied to these sources?

Research Question 1.6: How could monitoring tools developed for diffuse anthropogenic methane sources be utilized or adapted to support the monitoring, reporting, and verification of atmospheric methane removal technologies described in Research Area 2?

___________________

4 See https://www.epa.gov/research-grants/understanding-and-control-municipal-solid-waste-landfill-air-emissions-grants.

Research Area 2: Atmospheric Methane Removal Technologies

Chapter 4 of this report provided a preliminary assessment of atmospheric methane removal technologies based on information available at the time of writing. However, the knowledge base for these technologies—particularly their potential application and efficacy at atmospheric methane concentrations (2 ppm)—is very limited. Research on methane removal at 2 ppm can lower the concentration limit at which currently available mitigation technologies operate (~1,000 ppm; see Chapter 3). To advance knowledge about the technical potential of atmospheric methane removal technologies considered in this report, foundational research is needed to inform any phase-two assessment. This second assessment phase would examine technology feasibility against a set of criteria deemed to be appropriate at that time. The questions presented in this research area are intended to guide these technologies along a development path that would allow for the development of appropriate feasibility criteria. Outcomes from this research area will also inform Research Area 5 on applications of atmospheric methane removal. Questions in this research area are organized by the five atmospheric methane removal technologies considered in this report.

Methane Reactors

Chapter 4 detailed the major challenges for methane reactors to process large volumes of air containing low concentrations of atmospheric methane (necessitating notable energy input) to realize a climate-scale benefit. Energy needs of methane reactors are increased further by methane’s symmetric, small, non-polarizable, non-polar properties. Reactor operations and their reactive components that can efficiently process methane at ambient concentrations are part of an important research area. All reactive technologies described here should be assessed in the context of the overall energy balance of operation not only to ascertain what is technically possible but also to consider the energy use, critical materials supply, and eventually the cost of implementing the studied approach (see Chapter 5).

Research Questions 2.1–2.4 could be completed in the short term (1–5 years). Research Question 2.5 should occur over a longer-term timeframe, specifically 3 years after the start of Research Questions 2.1–2.4, and be completed over a 3–7 year timeline. Given the important role of reactor performance in determining the feasibility of this technology, the priority for these research questions is moderate. Accordingly, the Committee determines that a moderate amount of funding ($20 million) would be appropriate to support these research efforts. Assessments are likely to be calculation-based, process modeling studies informed by laboratory-scale experiments and available data from the literature. Relevant funding sources include the applied offices of U.S. DOE and interested private entities. As an indicator of demand for this type of research support, a philanthropic funding opportunity for atmospheric methane removal (excluding iron salt aerosol) in 2024 received 47 research proposals totaling more than $13 million and involving more than 100 researchers and 91 institutions (Spark Climate Solutions, 2024).

Research Question 2.1: How can technologies based on heterogeneous, inorganic methane combustion catalysts be enhanced to allow for combustion of atmospheric methane?

- How dilute can the methane concentration be while still allowing for efficient operation of a methane combustor?

- How can the temperature of operation of heterogeneous, inorganic methane combustion catalysts operating with feeds of <1,000 parts per million be reduced while limiting use of scarce elemental resources?

- How can designs be optimized for durability?

- Are there competing reactions from other atmospheric compounds that affect reaction rates?

Research Question 2.2: Biocatalysts will typically operate in an aqueous phase, while atmospheric methane is in the gas phase. Given the ultra-dilute nature of methane in the atmosphere, bioreactors operating at atmospheric methane concentrations will often be mass transfer–limited unless they incorporate materials that can overcome this limitation:

- Can changes to the matrix/composition of supported biocatalysts and/or efficient reactor designs enhance mass transfer and reaction rates for methane consumption using biocatalysts?

- If mass transfer is not limiting under conditions relevant to atmospheric methane concentrations, can genetic engineering or synthetic biology create new, more efficient methane-consuming biocatalysts that operate at low methane concentrations?

Research Question 2.3: Do other reactor types, such as those that use highly reactive intermediates like radicals or plasmas, offer the potential for atmospheric methane conversion to products with low global warming potential?

- Do non-catalytic reactors efficiently convert methane at 2 parts per million (ppm), 200 ppm, or 2,000 ppm methane concentrations?

Research Question 2.4: How low can the minimum methane concentration be pushed for different catalysts and reactors to still achieve acceptable catalyst durability, reaction rates, and energy use? The answer to this question sets potential concentration targets for product streams from methane concentrators.

Research Question 2.5: It can be instructive to consider the scalability and overall climate impact of different approaches if deployed at a scale that impacts atmospheric methane concentrations:

- Given the measured and/or calculated reaction rates for all of the previously discussed technology types, what land area would be needed for deployment of each technology to achieve climate-scale impacts? What energy source would be necessary to enable a positive impact on climate?

- What reaction rates would be needed for the different reactor technologies to achieve climate-scale impacts? How do these reaction rates compare to the measured/calculated rates for each reactor type?

- What would be the impacts on atmospheric circulation, atmospheric chemistry, critical materials and other resources, and global energy and land use of climate-scale deployment of each of these technologies?

Methane Concentrators

Methane has been a key feedstock for the oil and gas industries for more than a century. As such, considerable research and development has been focused on fractionation of streams containing methane and other light gases, as well as conversion to more valuable products. Owing to its unique physical properties, methane is an exceptionally difficult molecule to selectively sorb into liquids or onto solids and is rarely converted to more valuable products by routes other than through formation of synthesis gas (hydrogen and CO). Such technologies generally require concentrated methane feeds to create favorable economics. Similarly, the molecular size of methane is so close to that of nitrogen gas that membrane separations by molecular sieving are challenged at the ultra-dilute methane concentrations found in air. If a suitable material were to be identified, the energy requirement for moving huge amounts of air would also limit the scalability of methane concentrators (see Chapter 4).

Efficient methane sorbing materials and methane concentrators, should they be developed, would enable downstream technologies that might efficiently combust methane or convert methane into other useful products.

Research Question 2.6 can be investigated in the short term (1–5 years), with Research Question 2.7 beginning no sooner than 5 years following that effort (in a 5–10 year timeframe). Research Question 2.8 can be undertaken in the short term. All research questions for methane concentrators can be conducted at the laboratory scale. The Committee determines these research needs to be of relatively low to moderate priority for informing a phase-two assessment of atmospheric methane removal due to the early stage of this research, with relatively lower level of financial support required ($5 million–20 million). Potential funders include U.S. DOE Basic Energy Sciences, the relevant directorates of NSF (e.g., Engineering, Biological Sciences), and interested private entities. Given the amount of research progress that would be required for methane concentrators to reach viability, high-risk, high-reward funders like U.S. DOE’s Advanced Research Projects Agency–Energy or a prize-funding system like XPRIZE could be appropriate mechanisms for supporting this research.

Research Question 2.6: In the past few decades, new classes of adsorbents and solvents (collectively referred to as sorbents) have been developed:

- Can sorbents that efficiently concentrate methane from 2 parts per million (ppm) (bulk air concentration), 50 ppm (representative dairy barn concentration), or 200 ppm (representative coal mine concentration) to concentrations >100-fold higher upon desorption be identified? Similarly, can membranes that offer a similarly concentrated permeate be identified?

- When the separation materials are combined with a suitable air/sorbent or air/membrane contacting process, does the process offer suitable energy efficiency and projected cost to merit further research and development at larger scales?

Research Question 2.7: Among the most promising near-term engineered atmospheric methane removal technologies is catalytic combustion, owing to the maturity of the technology when using concentrated methane feeds. However, effective devices that can operate below ~1,000 parts per million methane in the feed are rare or unknown. Thus, methane concentrators that can produce enriched methane streams from more dilute feeds at levels suitable for methane combustors are an important target:

- What separators or arrays of separators can efficiently concentrate methane to the levels needed by methane reactors? After “minimum activation concentrations” are determined for different methane reactor technologies, their integration with suitable methane concentrators may be considered, seeking energy and cost-efficient combinations.

Research Question 2.8: Large industrial installations exist around the world today that separate the major components of air (e.g., oxygen, nitrogen, argon) for societal use. For industries with deep technology experience in this space, what would be the added energy use and cost required to concentrate carbon dioxide and/or methane from these existing processes?

Surface Treatments

Surface treatments containing catalysts rely on passive contact with atmospheric methane to convert it into a less radiatively potent product. Like methane reactors, efficient rates of oxidation of methane at relevant atmospheric concentrations will benefit these technologies. Additionally, due to exposure to the natural or built atmosphere, surface treatments will need to be effective within a relatively narrow temperature range compared to methane reactors. To be able to assess the climate-scale impact of surface treatments, additional fundamental knowledge into the rates of methane destruction under applicable reaction conditions is required for all proposed classes of materials (Research Question 2.9). These studies should be performed using actual or simulated gas compositions, reaction temperatures, and/or solar irradiance to be able to derive relevant reaction rates that would inform the efficacy of these interventions in a phase-two assessment of technologies.

Beyond methane removal reaction rates, information about the durability of surface treatments and potential co-benefits or conflicts is necessary to accurately assess the life-cycle impacts and cost of deploying this approach for comparison against other types of removal and mitigation approaches, should methane destruction rates be found to be potentially impactful at climate-relevant scales (Research Questions 2.10–2.13).

Development of the ability to directly measure the impact of deployed surface treatments on the nearby atmospheric methane concentration—for example, via very sensitive eddy flux covariance measurements or reliable models that describe the methane removal efficiency over the course of a surface treatment’s lifetime—is needed for reliable MRV (Research Question 2.14). Appropriate instrumentation may need to be developed to perform these measurements in a cost-effective and scalable manner.

These types of research activities are similar to those undertaken in materials science, catalysis, and sensing programs funded by federal research agencies. The research

activities span fundamental through applied science and technology development. The Committee estimates that this research could be conducted in the short-term (1–5 year) timeframe. Research Question 2.13 may be a longer-term study (5–10 years) after establishing whether effective surface treatments exist, but preliminary calculations could be done in the short term. A moderate amount of funding ($20 million) would be needed to advance research questions in this area, and potential funders include U.S. DOE’s applied offices, U.S. DOE’s basic science offices, the relevant directorates of NSF (e.g., Engineering; Biological Sciences; Technology, Innovation and Partnerships), and interested private funders.

Research Question 2.9: What are the reaction rates (for all catalysts) and apparent quantum yields (for photocatalysts) for methane destruction at 2 parts per million (ppm), 200 ppm, and 2,000 ppm?

- To what extent can reaction rates be increased by leveraging surfaces that are naturally warmed? What is the rate dependence on temperature?

- Can reaction rates be improved through better catalyst design?

- Can catalysts that do not use critical materials be identified?

- Can climate-relevant rates be achieved for any passive catalytic system?

Research Question 2.10: What are the most effective locations to deploy surface treatments (e.g., rooftop; heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning; exhaust fans on dairy barns or coal mines), considering methane concentration and the potential need to supply energy?

- If surface treatments were deployed in a dense area (e.g., urban environment), what are the rates of methane removal compared to natural atmospheric circulation? Is the removal rate large enough to cause a decrease in the local concentration of methane, and how does that impact performance? Could such surface treatments reduce the abundance of local air pollution (e.g., ozone or volatile organic compounds), thus improving human health?

Research Question 2.11: What is the durability or lifetime of surface treatments in their relevant environment (see Research Question 2.10)?

- What are the mechanisms of performance loss in catalytic surface treatments (e.g., catalyst attrition, fouling, poisoning, deactivation)? Can catalytic performance be restored in a cost-effective and low energy–intensity manner (e.g., washing)?

- What are the rates of deactivation of catalytic surface treatments under relevant atmospheric conditions?

Research Question 2.12: What are the air quality co-benefits or conflicts of using surface treatments?

- What other atmospheric species can be destroyed by surface treatments? If surface treatments can destroy other air pollutants (e.g., nitrogen oxides, volatile organic compounds), what are the relative rates of destruction at relevant atmospheric concentrations?

- If surface treatments do not completely oxidize methane to carbon dioxide, what other products are formed and what are their direct and indirect air quality impacts?

Research Question 2.13: What is the scalability of surface treatments, considering their effectiveness, materials required, and lifetime?

- Given the measured reaction rates of catalysts used in surface treatments (see Research Question 2.9), what surface area is needed to achieve climate-scale impacts? For photocatalytic surface treatments, this should include an estimate of the exposure to solar radiation.

- What reaction rates (or apparent quantum yields) would be needed for surface treatments to achieve climate-scale impacts if all human-made structure surfaces were to be coated? How do these reaction rates compare to the measured rates for each catalyst type?

Research Question 2.14: What tools are needed to measure the impacts of surface treatments at deployed scale, given that they are passive and open systems? Can reliable methods of measuring methane removal rates in a controlled environment be developed, applied, and validated in open systems? What is the necessary instrumentation and equipment needed to enable measurement and diagnostics?

Ecosystem Uptake Enhancement

Ecosystem amendments ultimately aim to accomplish atmospheric methane removal, emissions reduction, and sequestration of soil organic carbon simultaneously. Thus far, research on soil amendments in managed soils has shown which types of amendments can enhance and maintain the soil organic carbon pool by positively affecting physical, chemical, and biological properties of the ecosystem, and which have a net positive effect on GHG efflux (Abbott et al., 2018; Cayuela et al., 2013; Rubin et al., 2023). In degraded soils, restorative practices could be employed to enhance soil methane uptake (e.g., changes in water-filled pore space, bulk density, pH); in active agricultural systems, management practices could be undertaken to enhance soil methane uptake, including modified programs of irrigation or tillage (Research Area 1).

For atmospheric methane removal, metal-rich amendments (like rock dust) have started to be investigated, as trace elements like copper, iron, and lanthanides in such amendments can improve microbial methane consumption rates by switching the expression of central enzymes in the metabolic pathways of methanotrophic microbes (Semrau et al., 2018). In aquatic ecosystems including lakes, thawing permafrost, and expanding wetlands, amendments like phosphorous (Sawakuchi et al., 2021) and copper (Guggenheim et al., 2019) have been shown to enhance methane oxidation capacity and may also inhibit methanogenesis. For atmospheric removal, both soil and aquatic methanotrophs can be limited by similar factors—namely, access to trace metals, methane uptake capacity, oxygen availability or redox status, and rate of enzyme turnover. Research is needed to better understand how microbial populations in the methane

cycle are controlled by the localized biogeochemical constraints of their ecosystems and how redox potential and nutritional factors can switch an ecosystem from net methane production to net methane uptake. Factors limiting atmospheric methane uptake and removal by microbial communities at any one location can be alleviated during the formulation of an ecosystem amendment and the mechanism that will be used to deploy the amendment (e.g., surface spraying, incorporation into soil, injection into groundwater).

Plant surfaces offer an attractive option for atmospheric methane removal due to their large, globally distributed surface area; species diversity; and association with diverse biomes. Global tree planting programs are emerging around the world and could be leveraged for expanding atmospheric methane removal capacity on plant surfaces. While plants in wetlands and rice paddies are generally associated with methane emissions, other plants are active methane sinks, and some can switch between methane production and emission (Bastviken et al., 2023; Jeffrey et al., 2021, 2023). Key research needs in this area include which methane-cycling microbial communities are present and active on the surfaces of diverse plant species; whether atmospheric methane oxidizers can be engineered or adapted to live and thrive on plant surfaces; which plant types are most amenable to atmospheric methane uptake rather than methane emission; and how plant surfaces would be reached over large areas, particularly outside of intensively managed agricultural systems.

Related to these gaps is the need for better measurement and monitoring systems that can quantify the changes in ecosystem uptake as a result of amendments or management practices, as well as other consequences for ecosystem services, biodiversity, and nutrient cycling (see Chapters 4 and 5). Methane uptake varies both seasonally due to changes in climatic conditions and spatially due to differences in the chemical/physical properties of soil, microbial activity, and differences in vegetation (Bezyk et al., 2022; D’Imperio et al., 2023; Guckland et al., 2009). The ability to monitor and verify changes in ecosystem uptake will be essential to assess the effectiveness of potential future demonstrations for methane uptake and determine the economic return on investment.

Recommended short-term research (3–5 years) can be performed at the laboratory and research plot scales, with longer-term research (>10 years) at the landscape scale. The Committee estimates measurable progress on both amendment type and suitable geographical targets occurring within 3–5 years at a cost of $20 million–50 million. Progress on this research in time for any phase-two assessment is critical to determine whether deployable ecosystem amendments could have a measurable impact on atmospheric methane removal over a reasonable (e.g., 20 years) timeframe and over a sufficient geographical space. Advances in Research Area 1 (Research Questions 1.2 and 1.3) would complement the questions below. Funders for this research include U.S. DOE Biological and Environmental Research (BER), NSF, USDA, U.S. EPA, and private funders to allow for testing of a large breadth of amendment types and demonstration over a range of geographical areas and ecosystem types.

Research Question 2.15: What ecosystem amendments can augment the methane sink component to offset or overcome the methane production component, perhaps in synergy with other climate-active gases?

- Can amendments and materials be identified and/or engineered (at laboratory to research plot scales) to overcome mass transfer, methane capture, and nutrient limitations to stimulate the rate of atmospheric methane uptake by extant microbial communities at landscape scales?

- Can engineered microorganisms developed at laboratory and pilot scales be introduced to ecosystems for higher rates of atmospheric methane uptake at landscape scale?

- Do upland soils confer an advantage over flooded or lowland soils in supporting atmospheric methane oxidizing microorganisms over methane production?

- Do ecosystem amendments have unintentional consequences on other vital soil services (e.g., nitrogen cycle and nitrous oxide production, soil carbon sequestration), and how can these consequences be minimized and mitigated (with studies at laboratory scale but consequences at landscape scale)?

- Can large-scale production and transport of ecosystem amendments for broad application purposes be accomplished without contributing to greenhouse gas emissions (e.g., life-cycle analysis)?

Research Question 2.16: What is the strength and diversity of the plant/leaf/bark methane sink, and how can atmospheric methane uptake be enhanced on plant surfaces?

- What factors (e.g., nutrient, physical, microbiological, physiological, seasonal) control whether plants (leaves, bark, roots) are net methane consumers or producers?

- Can microbial populations associated with plants be modified or engineered to adhere to plant surfaces and grow on methane from surrounding air masses? Which plant species and ecosystems are optimal for enhancement or engineering of atmospheric methane removal on plant surfaces?

Research Question 2.17: What spatial and temporal scales are useful for measuring the rate of atmospheric methane uptake from ecosystem-scale amendments?

- How do climatic factors alter the rate of methane uptake, and can these factors be predicted and incorporated into long-term models of whether ecosystem amendments have a net positive effect on atmospheric methane removal?

- Do different measurement tools need to be developed and/or deployed to measure methane uptake rates from land-based, aquatic-based, and plant-based systems effectively? Are different measurement tools needed to robustly monitor, report, and verify ecosystem interventions, taking into account large spatial variability?

Atmospheric Oxidation Enhancement

AOE technologies include chlorine- or hydrogen peroxide–based methods in which natural processes that oxidize methane in the atmosphere would be accelerated. Chapter 4 identified large uncertainties in the scale and duration of material that would need to be added to the atmosphere to realize a climate-scale impact, and Chapter 5 identified large uncertainties in the potential consequences of these technologies on atmospheric

composition. Key research needs are outlined below to advance understanding of the chemical mechanisms of chlorine- and hydrogen peroxide–based AOE technologies, their technical potential, and potential unintended consequences. The research outlined in Research Area 1 on atmospheric methane sinks would also improve understanding of AOE.

Large uncertainties remain in the mechanism of chlorine release from iron salt aerosols—one of the chlorine-based AOE methods. Laboratory studies of this mechanism are needed to inform understanding of whether this AOE approach would be viable in the atmosphere. Sufficient laboratory studies have not been conducted on which iron species efficiently produce chlorine radicals and catalytically cycle under true atmospheric conditions; laboratory conditions have shown atmospheric sulfate suppresses the relevant reactions (Mikkelsen et al., 2024; Wittmer, Bleicher, et al., 2015; Wittmer & Zetzsch, 2017). Gorham et al. (2024) provide examples of laboratory and field studies that would improve understanding of the iron salt aerosol mechanism. Horowitz (2024) also suggests that laboratory studies of natural and engineered iron salt aerosol, including mixtures with ambient species, are needed to improve the understanding of chemical kinetics in addition to experimental measures of bromine species released from natural and engineered iron salt aerosols.

Recent observations have suggested that small amounts of methane (0.6 Tg yr-1) are oxidized by halogens that are activated by large amounts of natural iron in the atmosphere (120 Tg) (van Herpen et al., 2023). However, the relevant halogen chemistry is generally neglected in chemistry-climate models, and the few models that do include halogen chemistry find qualitatively similar but quantitatively different model responses (Horowitz, 2024; Li et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2021). Quantitative differences in model responses could be due to a variety of reasons including different halogen chemical mechanisms, spatiotemporal resolution, and model run times. Uncertainties also persist in model parameterizations of halogen chemistry. The addition of sufficiently large amounts of chlorine to remove atmospheric methane would require models to simulate a different, halogen-dominated photochemical regime than the current chemical regime for which models have been optimized and observationally constrained, posing challenges for model evaluation. Model uncertainties represent a challenge in assessing the efficacy of modeled AOE technologies on the methane lifetime and, more generally, the chemical composition of the atmosphere.

Additionally, AOE technologies would require continuous application of Cl2, iron, hydrogen peroxide, or other species to theoretically realize climate-scale impacts (see Chapter 4). Many unknowns regarding these applications remain; for example, what form of iron should be added, and the particle size and duration at which the iron would stay in a reactive form in the atmosphere. Chapters 4 and 5 also describe an inflection point at which models of AOE technologies change from being climate-detrimental to climate-beneficial—an area that requires further investigation. Additional questions remain about the local and global consequences of AOE technologies on atmospheric composition (see Chapters 4 and 5).

Research Question 2.18 could be investigated through laboratory studies, large chamber experiments, and/or field observations prior to the consideration of AOE

demonstration or deployment. Research Question 2.19 identifies modeling research that should be addressed prior to the consideration of AOE demonstration or deployment. The Committee recommends that Research Question 2.19 be carried out through a model intercomparison project in which halogen chemistry would be implemented into multiple chemistry-climate global models. Research Question 2.20 could be investigated through a combination of modeling studies, field observations, and/or laboratory chamber experiments and should also be addressed prior to the consideration of AOE demonstration or deployment. This research could be carried out over a period of 5–10 years for $5 million–20 million. U.S. DOE-BER, NASA, NOAA, and NSF would be well suited to fund this work.

Research Question 2.18: For the iron salt aerosol chemical mechanism, which iron species are photoactive and efficiently produce chlorine radicals under atmospheric conditions?

- What are the sources and distributions of photoactive iron currently in the atmosphere?

- Under what conditions does natural or engineered iron salt aerosol continuously produce chlorine radicals?

- What bromine species are released from natural and engineered iron salt aerosols? How would these species affect the efficacy of chlorine radical production?

Research Question 2.19: What is the impact of increasing the sources of halogens (e.g., chlorine and bromine) on the oxidizing capacity of the troposphere and the methane lifetime?

- How well do current chemistry-climate models reproduce observations (e.g., carbon isotopes, methane, hydroxyl radicals, halogens, by-products of methane oxidation) (see Research Question 1.1)? What improvements are needed?

- What is the impact of increasing halogen sources on ozone-depleting substances and stratospheric ozone?

- What is the impact of increasing halogen sources on surface air quality (e.g., ozone and particulate matter) and clouds?

- How sensitive are the aforementioned changes to the implementation of coupled tropospheric halogen (i.e., chlorine, bromine, iodine) chemistry in different chemistry-climate models?

Research Question 2.20: For chlorine- and hydrogen peroxide–based atmospheric oxidation enhancement (AOE) technologies, what is the magnitude of molecules (e.g., chlorine gas, hydrogen peroxide, iron salt aerosols) required for a climate-scale impact? What is the inflection point at which AOE technologies change from a net climate benefit to a net climate detriment?

- For each AOE technology, how does this inflection point vary regionally, temporally, and with the local chemical regime?

- How are modeling results dependent on uncertainties in hydroxyl radical and nitrogen oxide concentrations and chemistry in models?

- How can observations of natural analogs (e.g., ship tracks, iron-containing dust) improve understanding of chemical mechanisms and improve model representations?