Review of the Department of Veterans Affairs Presumption Decision Process (2023)

Chapter: 4 Scientific Aspects of the Presumption Decision Process

4

Scientific Aspects of the Presumption Decision Process

The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) states that the purpose of its pre-decisional document Improving VA’s Presumptive Decision Process is to “describe a new process the VA will use to evaluate whether a specific medical condition is or is not associated with an environmental exposure. If an association is found, this document further describes how the condition could reach presumptive status.” In this chapter, the committee focuses on the scientific methods proposed by VA to evaluate a potential association, up to and including a determination of the likelihood of the association and a presumption recommendation.

The chapter is structured in the order of the steps in the presumption decision process that VA uses for evidence review, as understood by the committee: (1) the overall scientific approach, (2) the planning and preparatory phase, (3) a standardized scientific assessment, and (4) a final phase in which conclusions are drawn regarding the likelihood of a positive association. Collectively, these steps encompass aspects of the VA presumption decision process document relating to the types of evidence (e.g., section 6 components); use of PECOTS (population, exposure, comparator, outcomes, timing, and setting)1 and GRADE (grading of recommendations assessment, development and evaluation) methods (section 7); and determination of the likelihood of a positive association (section 5). In the next sections, the committee describes each of these steps as given in the document, provides key findings, and offers conclusions and recommendations to improve the clarity

___________________

1 In PECOTS the “p” is defined as either “population” or “patient.” The committee chose to use population because patients are considered a subset of population.

and conduct of the scientific aspects of VA’s presumption decision process. In making recommendations, the committee recognized that the scientific process must be fair, consistent, transparent, and veteran centric.

OVERALL SCIENTIFIC APPROACH

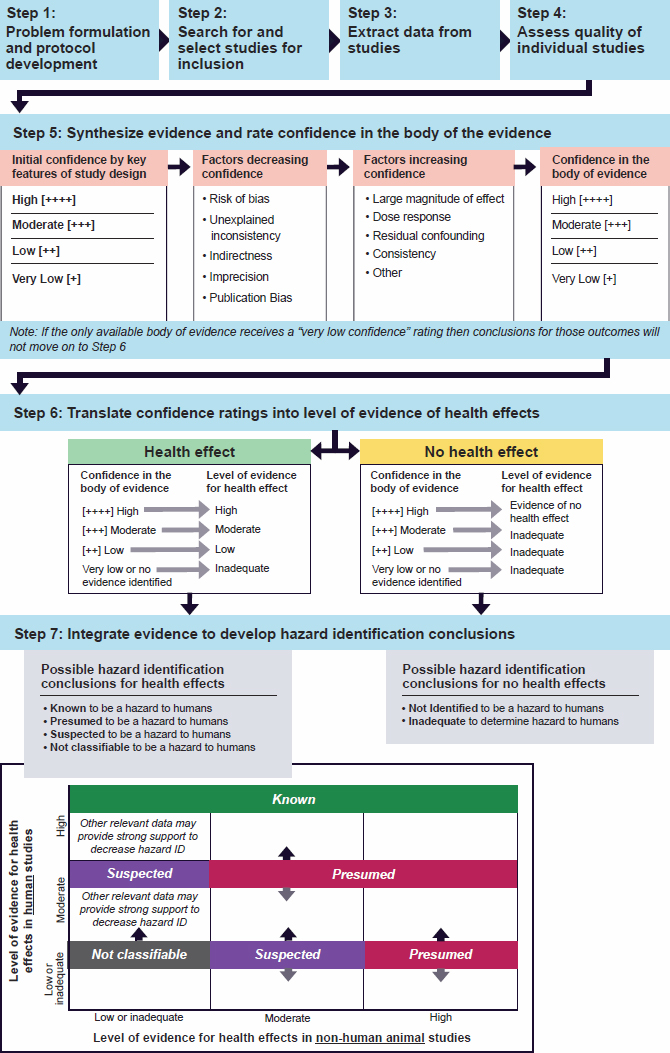

The scientific aspects of the presumption decision process are presented in VA’s pre-decisional document in section 3 “Selection of Conditions,” section 5 “Equipoise,” section 6 “Components and Methods That Are Part of the Review Process,” and section 7 “Standardized Evaluation of the Science.” The flow diagram in the VA presumption decision process document (see Figure 4-1) shows six discrete steps, several of which include data collection, evaluation, and synthesis. These sections and steps are briefly described later. A more in-depth discussion of the planning and preparatory phases, a standardized evaluation, and the evidence to recommendation process follows this overview.

Section 3 “Selection of Conditions” briefly states that VA will use a number of data sources to develop a list of medical conditions to be considered for a presumption and considers factors such as number of veterans affected, condition severity, amount of literature available, and Veterans Health Administration (VHA) and/or Veterans Benefits Administration (VBA) data trends (see Chapter 3 for a complete description). When or how these data sources are screened or what criteria will be applied to them (e.g., how many veterans need to be affected or how severe a condition must be to be considered) are not presented. VA indicated that section 3 is the same as box A in the flow diagram (“Preparatory Phase”) (VA, 2023b). The ongoing and iterative nature of activities related to condition selection, such as developing a preliminary and a final list of conditions to be considered, is not clear in the presumption decision process document text or flow diagram.

Section 5 “Equipoise” briefly describes the concept of equipoise and provides the four standards applied to the evidence for a presumption. Section 5 is discussed in more detail later in this chapter, as it would be the last step in developing a presumption document for a condition. The likelihood of a positive association would be determined in item 6 of box D in Figure 4-1.

Section 6 “Components and Methods That Are Part of the Review Process” shows five subsections relating to data types (health care data, scientific literature, VBA claims data, other factors, and rare conditions). This section provides minimal information on the types of data that could be reviewed and virtually none on the methods for data evaluation or how any data are integrated into a presumption recommendation.

The list of data types in section 6 largely mirrors the legislative language in the 2022 Sergeant First Class Heath Robinson Honoring Our Promise to

NOTES: DOD = Department of Defense; HOME = Health Outcomes Military Exposures; MeSH = Medical Subject Headings; NASEM = National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; OCLA = Office of Congressional and Legislative Affairs; OGC = VA Office of General Counsel; SecVA = Secretary of VA; USH = VA Undersecretary for Health; VA = Department of Veterans Affairs; VBA = Veterans Benefits Administration; VHA = Veterans Health Administration.

SOURCE: VA presumption decision process document (2022); boxes have been labeled (A–F) by the committee for clarity.

Address Comprehensive Toxics Act (PACT Act) (PL 117-168), Section 202 §1173, which specifies the evidence, factors, and data that VA is to include in any formal evaluation (see Appendix A for the relevant passages of the legislative language). The committee considered the VA components and methods for obtaining and reviewing the scientific literature (section 6B), VA epidemiologic research studies (section 6A), and VA’s approach to rare conditions, particularly cancers (section 6E). These components appear to also be cited in the flow diagram (Figure 4-1) in boxes A and B. All of these components are discussed later in the chapter in the section on Evidence Identification and Selection.

Section 7 “Standardized Evaluation of the Science” addresses concepts, tools, and approaches that are important for evidence-based assessments. Subsection 7A describes the use of a PECOTS framework to “define the strength of the evidence base.” Subsection 7B contains a brief explanation of how data are extracted from evidence sources to expedite an evaluation. Finally, subsection 7C is a short statement that VA uses “a semi-quantitative approach to evaluate the quality of evidence” using the GRADE framework. Section 7 appears to correspond with box D, although the exact steps do not align with the subsection text. Moreover, Figure 4-1 and the text of the presumption decision process document do not identify who the peer reviewers noted in box E, item 1 are (e.g., internal, external, expertise); how they are chosen; or what they are asked to review.

Figure 4-1 includes a description of the proposed VA-led review process but also refers to reviews that would be externally conducted (box C). Where and how an external review, such as a consensus report from the National Academies, is incorporated into the evidence review process is not stated in the document text or shown in the flow diagram.

PLANNING AND PREPARATORY PHASE

In the context of scientific best practices, and specifically for medical condition assessments, problem formulation is the first step in the planning and preparatory phase (e.g., NTP, 2019). The steps in this phase provide context and background to the topic, define the specific research question around the medical condition (topic), and determine the specific methods that will be used to evaluate the research question, as described later. In the presumption decision process document, a planning phase occurs for two separate functions. The first is the identification, prioritization, and selection of medical conditions to include on the list to be considered for evaluation; the list is published in the Federal Register at least once a year. The second function is to begin the review process for a specific condition(s); the planning phase typically will begin after condition selection and determines the method (e.g., a systematic review) to be used to conduct the review.

The committee regards the first three boxes (A, B, and C) and the first three steps in box D in Figure 4-1 to collectively represent a planning and preparatory phase of the review process for a specific condition, although this is not explicitly stated in the document. It is unclear whether the boxes, particularly A and B, also correspond to section 3 on selecting the conditions to consider for presumption. Other aspects of the planning and preparatory phase are addressed in sections 3 and 6 of the VA presumption decision process document.

In the following two sections, the committee assesses the scientific aspects of condition selection and the determination of review type (see Chapter 3 for governance of condition selection) that are part of the planning and preparatory phase of the presumption decision process document. Another aspect of that phase—developing specific research questions (PECOTS) and a research protocol—is discussed in the later section on conducting a standardized evaluation.

Selection of Condition (Topic)

The presumption decision process document provides little or no description of the criteria or processes used to identify and prioritize medical conditions (topics) for evaluation. The committee agrees with VA on the need to leverage a variety of data and evidence sources to inform the selection of physical or mental conditions; VA will need to rely upon different sources of data and evidence, as it indicates in section 6 and Figure 4-1, box A.

The distinction between the first two steps of the process—shown in Figure 4-1 (box A and box B)—is unclear. Both generally address condition identification, prioritization, and selection. Condition identification and selection appear to entail proactive monitoring of internal VA data (health, mortality, and claims data) and exposure data from the Department of Defense (DoD) and environmental agencies, such as the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Determination of conditions to review may also be based on external factors, such as congressional mandates, direction from the VA Secretary, a review of a National Academies report, and solicited responses to a Federal Register notice. Artificial intelligence/machine learning is also described as an approach to assist with the continuous review of scientific literature to help with condition identification and selection, but no details identify the software tools that will be used to implement this or specifically how these methods will be used to evaluate the scientific literature.

The committee finds that the presumption decision process document text and figures are unclear on exactly how each data source at each

step would be identified, reviewed, and analyzed, and how the results of these analyses of disparate data sources (e.g., VHA data, VBA claims data, National Academies reports, and public comments) would be integrated to inform the decision process for condition selection. Examples of details that are lacking include the following:

- What data sources (in addition to VHA health care data, VBA claims data, and exposure data from ATSDR, DoD, and EPA) would be monitored or surveilled and how these would be incorporated at the condition identification and selection phase relative to other steps in the scientific process;

- How these data sources would be monitored or surveilled and at what time intervals to incorporate newer data/evidence;

- How input from the Federal Register notice would be used, and what other mechanisms to solicit stakeholders’ input (specifically members of the affected community) would be used;

- What criteria would be used to prioritize and select conditions for review; and

- What criteria or factors inform the decisions for a VA-led versus an externally conducted review and selection of review type (e.g., de novo systematic review, rapid review; see next section).

The committee concludes that insufficient details are provided on condition identification, prioritization, and selection, either for the list of medical conditions to be considered for presumption or for condition-specific evaluation, in the presumption decision process document to assess how these steps would be conducted.

Determination of the Review Type

VA stated that the determination of whether to conduct an internal (VA-led) or external (e.g., the National Academies, ATSDR) review is largely based on size and complexity of the evidence base, the potential controversial nature of the condition, the need for additional subject matter expertise, and—most importantly—time (VA, 2023c). As noted in the background (section 2) of the presumption decision process document, VA believes that its proposed revised process will expedite the presumption decision process for many conditions and reduce the need to wait for National Academies consensus reports, which may take up to 2 years to complete and frequently examine several exposures or conditions in a single report. VA may also use data, such as VBA claims, that are not available to external agencies or organizations.

Scientific best practices for standardized assessments of the potential link between environmental hazards and the development of health

conditions involve methods such as systematic, rapid, and scoping reviews. The committee notes that VA may require any of these types of reviews whether the review is to be conducted by VA or by an external organization. Each type of review is briefly discussed next.

A systematic review provides a structured approach to evaluate a specific research question (or set of interrelated research questions). It promotes transparency and objectivity based on the use of specific methods for designing, conducting, and reporting a review. It relies on established methods, including systematic identification, appraisal, and evaluation of the evidence. EPA, the National Toxicology Program (NTP) at the National Institute for Environmental Health Sciences, the World Health Organization (WHO), and the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) all use systematic reviews to support their decision-making processes for environmental health. Guidance on conducting systematic reviews is available from several organizations including WHO (2021), Cochrane (Higgins et al., 2022), and Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) (Page et al., 2021).

Systematic review methods are designed to arrive at an estimate of effect or association with some precision and understanding of the certainty of the estimate (IOM, 2011). For some conditions that may have a large body of scientific evidence, a systematic review may be costly, resource intensive, and slow; however, not every condition or exposure will require a de novo systematic review, particularly if the primary purpose of the VA presumption decision process is to determine a 50% probability threshold for a positive association between an exposure and a condition (in which precision of the magnitude of effect may be less important). For example, systematic reviews from the scientific literature (e.g., Cochrane reviews) or authoritative agencies (e.g., NTP) could be used directly to make decisions, serve as the starting point for conducting or updating a review, or define or refine the research question. Although box C of Figure 4-1 references external reviews, VA does not explain how systematic reviews or reports from the National Academies or other organizations will be evaluated and incorporated into the body of evidence. To enhance the assessment of systematic reviews, VA may opt to use tools, such as ROBIS and AMSTAR-2,2 to evaluate their validity or quality.

An adaptive or iterative approach to planning and executing the scientific process would allow for an accelerated workflow in some instances and judiciously allocate resources to where they are needed. An adaptive approach

___________________

2 ROBIS (Risk of Bias in Systemic Reviews) is a tool designed specifically to assess the risk of bias in systematic reviews; AMSTAR-2 (A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews) is a 16-item assessment tool to check the quality of a systematic review and establish whether the most important elements are reported (Perry et al., 2021).

assumes that not every topic necessarily requires a full de novo systematic review. The decision on whether it is necessary to proceed to the next step has to do with the evidence base, which is typically characterized during problem formulation. A scan of the evidence during problem formulation can identify existing systematic reviews or other types of evidence products (e.g., rapid reviews, scoping reviews) that may be sufficient to determine the likelihood of a positive association without the need for conducting a new systematic review. In these cases, another evidence synthesis may not need to be conducted if criteria for a quality systematic review are met.

Scoping reviews are used to determine the scope or coverage of a body of literature on a given topic and give clear indication of the volume of literature and studies available and thus may be helpful as part of the overall scientific process (Munn et al., 2018). Guidance on conducting scoping reviews is available, for example, through the Joanna Briggs Institute and Cochrane (Peters et al., 2015; Tricco and Oboirien, 2017).

A rapid review is a form of evidence synthesis that incorporates some elements of systematic review but simplifies or omits other elements. Guidance on best practices for conducting rapid reviews is available. Both WHO and Cochrane have issued guidance that is relevant (Garritty et al., 2020, 2021; Tricco et al., 2017).

If a de novo systematic review is needed (i.e., existing evidence syntheses are not sufficient to determine “equipoise”), a scan of the existing evidence would provide the necessary information to assess the criteria on whether to pursue an internal VA-led rapid review versus an externally conducted review. It could also be used to identify where the current scientific evidence may be sufficient or lacking, thus informing a more efficient systematic review design.

Deficiencies in systematic reviews and meta-analyses could be elucidated using a gap analysis method, which is the multistep process of identifying and defining existing gaps in information or methods and analyzing (possible) reasons for those gaps, to propose and develop approaches to close, mitigate, or compensate for them (Sheard and Steeves, 2018). In-depth assessment of existing systematic reviews and meta-analyses can reveal gaps in methods (tools and techniques) as well as findings; these gaps may be the result of limitations in the tools and techniques available when the studies were reviewed (i.e., they are not up to date). In such cases, it will be important to assess if and to what extent limitations and constraints in tools and methods have been addressed, mitigated, or remain.

The committee finds that the presumption decision process document has insufficient details to determine if the approach for the planning and preparatory phase (condition identification, prioritization, selection) is consistent with scientific best practices.

The committee finds that the presumption decision process document text and figures are unclear on exactly how each data source at each step would be identified, reviewed, and analyzed. In addition, the committee finds that the document lacks details to assess components, criteria, and methods related to the selection of the review type.

CONDUCT OF A STANDARDIZED EVALUATION

A standardized evaluation process will help ensure the consistency and transparency of VA’s assessments and decisions. In section 7 of the presumption decision process document (Figure 4-1, box D), VA describes the standardized process to evaluate the scientific evidence for a condition. Section 6 of the document identifies the components and, to a lesser extent, the methods that will be used in section 7, which consists of three subsections: A. PECOTS framework; B. extraction of key data elements from evidence sources to facilitate evaluation; and C. determination of levels of evidence. In this section, the committee considers all of these sections as well as how individual scientific studies might be reviewed in the standardized evaluation process. It begins by describing scientific standards for environmental health assessments that have been developed by other organizations and are widely accepted as best practices.

Scientific Standards for Environmental Health Assessments

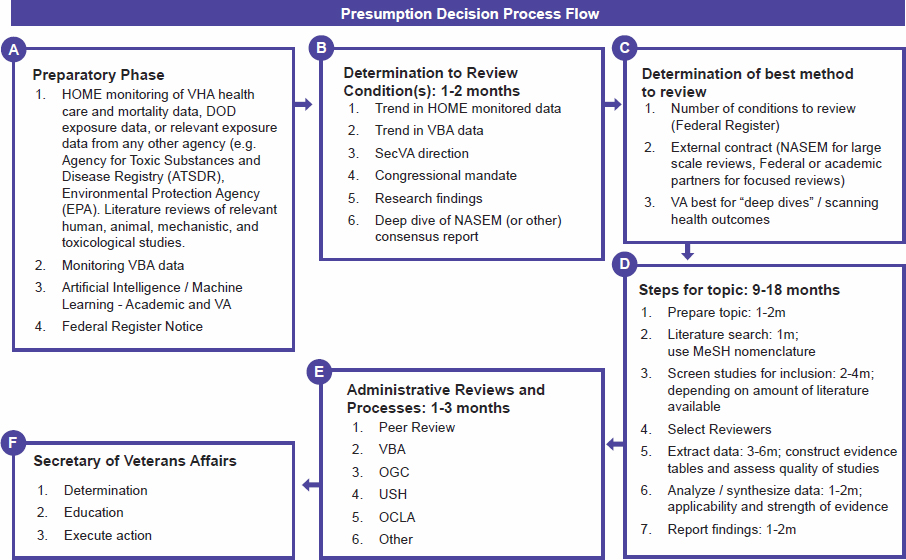

Numerous organizations involved with assessing potential associations between exposure to environmental hazards and the development of health conditions—such as NTP at the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, EPA, WHO, and EFSA—use methods, such as systematic reviews (e.g., EFSA, 2010; EPA, 2022; NTP, 2019; WHO, 2021), as part of an evidence-based environmental health assessment process. The committee considers the methods described by EFSA, EPA, NTP, and WHO to be the scientific best practices for using a systematic review to address environmental health research questions, and its findings are discussed in the context of those standards. The general steps involved with an evidence-based assessment include problem formulation (assessment planning, discussed in the prior section), protocol development, evidence identification and selection, individual study assessment (including critical appraisal), body of evidence assessment (including synthesis and evaluation of the confidence or strength of evidence), and reporting.

These steps are explained in depth in the NTP Handbook for Conducting a Literature-Based Health Assessment Using OHAT Approach for Systematic Review and Evidence Integration, which contains the NTP Office of Health Assessment and Translation (now the Integrative Health Assessment

Branch) approach for systematic review and evidence integration (NTP, 2019). Figure 4-2 provides an example of NTP’s systematic review and evidence integration process to assess potential environmental hazards; it may be broadly applicable to VA’s process, but other systematic review processes such as those of WHO and EPA may also be used or adapted by VA. The committee’s findings with regard to VA’s description of its standardized methods are described based on these general steps of an evidence-based assessment, recognizing that they occur after problem formulation and protocol development.

The steps at which evidence is used to estimate the likelihood of a positive association and develop a presumption recommendation (box D, steps 5–7) are not clear; however, in response to a committee query for clarification, VA (2023b) stated the following:

The development of evidence tables in item 5 would invariably entail assessment of the data and discussion of the extent to which assembled evidence and review support equipoise. In item 7 the determinations and recommendations would be presented in a report (with recommendations) for referral to the Administrative Reviews in Box E.

The committee finds that, in general, the flow diagram in the VA presumption decision process document (Figure 4-1) is logical, beginning with a planning and preparatory phase, determination of conditions to review, and determination of methods for the review, followed by a scientific review by VA or an external entity.

The committee also finds that VA’s explanation does not define its decision-making criteria for how it will use the evidence synthesis to determine the strength of association between the exposure and medical condition in question, particularly given the potential use of disparate evidence streams. The evidence-to-decision process also is not defined.

Development of a Specific Research Question and Research Protocol

It is widely recognized that a clearly framed question is critical to defining research objectives for the conduct of evidence-based assessments, and it is typically developed during the planning and preparatory (problem formulation) phase. Guidance is available for developing such structured questions or objectives in context of environmental exposures and health conditions (Morgan et al., 2018; WHO, 2021). One approach is a PECOTS-based or similar framework. PECOTS is used to guide the development of a protocol that specifies the scope and research questions in detail; the protocol also outlines the methodology for conducting the evidence review.

In the context of environmental health and scenarios of likely interest and applicability to VA, such a protocol may include examination of the incidence or prevalence of the condition and its onset, severity, and etiology; exposure considerations may include the duration, frequency, and concentration of the environmental agent. The PECOTS framework helps inform and guide all steps in the review process—beginning with selection of evidence and ending with developing conclusions that are a direct response to the PECOTS-based research question. Typically, the structured research question informs the development of the specific review methods and helps refine the literature search strategy and screening for applicability. The appraisal and evaluation of evidence is then conducted in the context of the research question, and conclusions are made in direct response to it. In scientific best practices, the structured question and methods would be documented in a protocol before the review. Examples of PECOTS tailored to environmental health are discussed in Morgan et al. (2018).

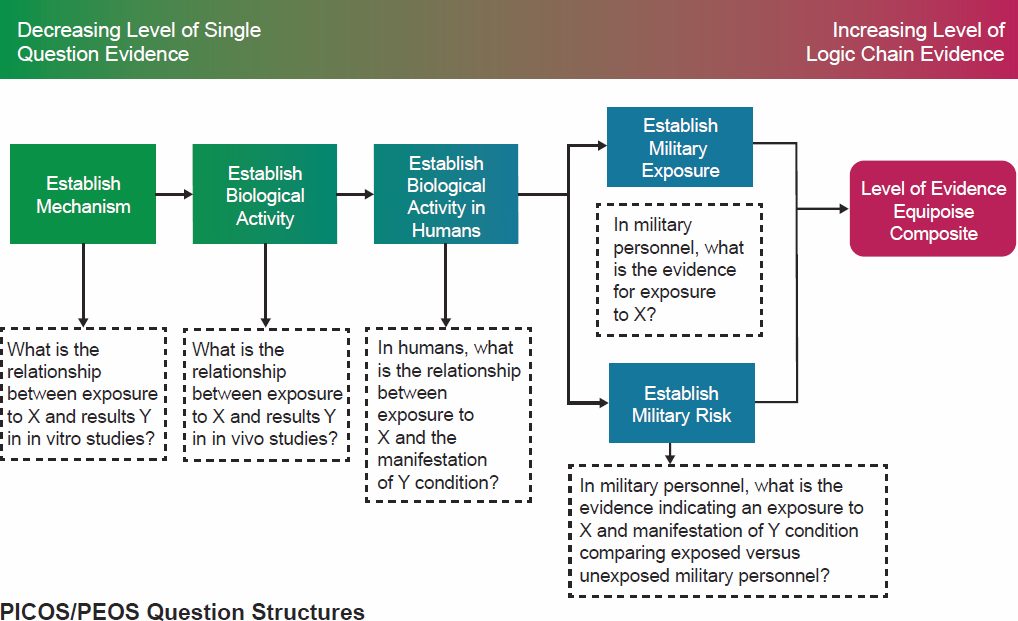

Section 7A of the VA presumption decision process document is titled “PECOTS Framework,” but VA’s use of PECOTS and the corresponding figures and content are not consistent with standard use of this term. That is, VA states that the condition-specific review panels will use “a consensus-based evaluation process that incorporates and adapts the PICOTS (Patient, Intervention, Comparator, Outcomes, Timing, Setting) Framework to define the strength of the evidence base.” VA substitutes exposure (E) for interventions (I) in its description of PECOTS in section 7A. The committee agrees that it is appropriate to consider techniques and concepts whereby the focus is on exposure as used in toxicology versus interventions (I) such as in PICOTS, the latter of which is more commonly used in clinical medicine. However, the committee notes that PECOTS is not generally recognized as a consensus-based evaluation process; as described in the presumption decision process document, VA presents PECOTS as more of an evidence-to-decision framework, so it is misused. The committee notes that VA used an appropriate PECOTS framework and description (see Table 4-1) in its rule for “Presumptive Service Connection for Respiratory Conditions Due to Exposure to Particulate Matter” (Federal Register, 2021) but that a shell or example of such a table was not included in the presumption decision process document. Table 4-1 shows VA’s PICOTS terms and the criteria for the human and nonhuman studies to be reviewed for the rule as would be expected when determining the scope of the literature search and the criteria for it.

The committee interpreted the PECOTS schematic (Figure 4-3) to broadly demonstrate how various sources of scientific literature might be used together to determine a level of evidence and “equipoise composite” (this term is undefined and not described in either the text or the flow diagram in the presumption decision process document). This schematic helps the reader to achieve a very high-level understanding of the

| PICOTS term | Human studies | Non-Human studies |

|---|---|---|

| Patient Population OR Problem | Adults (18-50 years) | Relevant model systems (e.g., in-vitro, in-vivo). |

| Intervention OR Exposure | Chronic exposure to particulate matter (PM2.5) air pollution | Acute/chronic exposure to PM2.5. |

| Comparator | No exposure (or fine PM levels < federal guidelines) | No exposure. |

| Outcomes | ICD-9/10 codes for respiratory conditions and/or biomarkers consistent with these conditions | Respiratory condition phenotypes and/or observed behaviors. |

| Timing | Months to years | Days to months. |

| Setting | All countries | Not applicable. |

NOTE: ICD = International Classification of Disease; PM = particulate matter.

SOURCE: Federal Register (2021).

evidence-to-decision process. An evaluation of evidence is frequently based on multiple levels and types of information that may be acquired from mechanistic studies, biologic activity (in vivo) studies, and studies of activity in humans—that is, from multiple evidence streams that may be derived collectively from observational, investigational, and clinical studies—however, not every scientific review will involve each or all of these evidence streams. For example, during the planning and preparatory phase of the problem formulation, it would be determined if mechanistic data (or evaluation of mechanism) would be necessary to address the research question. An understanding of the mechanism, or biologic plausibility, for an environmental agent may or may not be important to establishing the likelihood of a positive association for each condition. To be consistent with scientific best practices, VA would identify if and what mechanistic data would be needed for an evaluation as part of problem assessment and protocol development. Because these data are very complex, they would be evaluated only when an assessment of biologic plausibility is necessary, such as when direct evidence is insufficient to assess the relationship between an exposure and a condition or the evidence is contradictory. Following an evaluation of the body of evidence, the findings from an evidence stream (e.g., human studies) are integrated with the findings from other evidence streams (e.g., animal, mechanistic) to reach a conclusion.

Figure 4-3 also indicates a need to establish military exposure as well as military risk. The figure indicates the types of evidence that might be used

to support a determination of “equipoise”; however, the arrows are confusing, as this is not a flowchart on how to reach such a determination. This diagram is not a PECOTS research question. Strictly speaking, the dotted box with an arrow originating at the box “Establish Biological Activity in Humans” might be constructed as the actual PECOTS research question for the presumption process.

“Artificial Intelligence/Machine Learning, Academic and VA” is mentioned only once in the VA presumption decision process document in section 6: “In the future and when possible, the use of machine learning algorithms and text-mining tools for continuous review of scientific literature will be used.” No details are provided that identify the software tools that will be used to implement this or specify how these methods will be used to identify evidence (e.g., review of abstracts), extract the scientific literature, or synthesize the results. The committee notes that “artificial intelligence” is not a catchall term; it includes various forms of machine learning that incorporate big data into usable algorithms and practice. Big data technologies and techniques may be appropriate to assist with scoping the volume of information in the planning and preparatory phase. However, the degree to which these methods have been developed and validated for use in subsequent steps of the scientific process varies, so how these technologies are to be incorporated into the review will require careful consideration.

Last, to be consistent with scientific best practices, a written work product (e.g., a protocol, assessment plan, scoping review) is developed as the output of the planning and preparatory phase to provide the information necessary to prioritize, select, and determine how to review each condition and typically includes information gathered from a variety of sources, including database searching for reviews and large observational studies. Existing reviews could include nonhuman studies (e.g., those addressing mechanistic or biologic evidence in animal or in vitro models), if applicable. However, the work product would clearly describe how these study types would be incorporated into the overall evaluation.

The committee finds that, given the variety of conditions to be evaluated and the differences in the amount, type, and quality of the evidence to be reviewed for any condition, the scientific evaluation process will need to be flexible to address the research question that is formulated using PECOTS.

The committee concludes that the PECOTS terminology, the PECOTS schematic (including its content, order, and organization), and the accompanying text in the presumption decision process document are not consistent with scientific best practices.

Evidence Identification and Selection

In this section, the committee examines sections 6 and 7 (Figure 4-1, boxes A and D) of the presumption decision process document that present what and how scientific information will be identified and selected for further analysis.

Section 6 “Components and Methods That Are Part of the Review Process” lists five data types or components: health care data (6A), scientific literature (6B), VBA claims data (6C), other factors (6D), and rare conditions (6E). For each subsection, the committee describes its contents and makes findings where appropriate.

Health Care Data

The presumption decision process document indicates that VA will review VHA data in the form of epidemiologic research studies and ongoing health care and population surveillance (subsection 6A, which corresponds to Figure 4-1 box A, item 1); however, no additional information is given on what these data are or the methods used to review them. The committee notes that VHA data will only capture those veterans who are enrolled in VA health care, omitting the millions of veterans who are not, so information on health conditions for all veterans is incomplete. In addition, the presumption decision process document does not indicate whether these epidemiologic studies are ongoing (especially if being conducted by VA researchers) or completed and how their data will be used. The use of ongoing health care and population surveillance data can be problematic as there is no indication of what medical conditions will be surveilled, when, and how often. Will the many VA registries—knowing their myriad problems with representativeness and breadth, among other factors—be used as a source of information, for monitoring or otherwise? If not, how will other health care data, presumably from VA electronic health records, be identified and used?

The committee finds that this section has insufficient information to determine what VHA data will be used and how they will be obtained and evaluated. The committee also finds no description of how this information will be incorporated into the presumption decision process for condition list generation or condition-specific reviews.

Scientific Literature

Scientific literature is listed as the second type of evidence to be considered in the review process (section 6B) following VHA health care data. The description of the methods to be used to assess scientific literature is overly

general, and it is unclear whether this literature will be weighted differently in the review process given its presented order. For example, Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) keywords are indicated as a method for identifying military and civilian human, animal, toxicologic, and mechanistic studies; however, MeSH is not a method but rather a controlled vocabulary thesaurus used in the National Library of Medicine’s MEDLINE database, so this alone may not be sufficient for a search strategy, as it can be too limiting due to the way studies are indexed and labeled. A protocol for the review and evaluation process would typically include information on developing and implementing a comprehensive search strategy that would include the databases that would be searched, approaches to develop the search terms specific to each database (e.g., MeSH in MEDLINE, Emtree in Embase), and other aspects that would be considered in the methods to identify and select scientific literature (corresponding to box A, items 1 and 3, box D steps 2, 3, and/or 5). This aligns with best practices in searching the scientific literature for a systematic review.

This subsection also has a brief mention of future use of “machine learning algorithms and text-mining tools for continuous review of scientific literature.” As the use of such tools is speculative, the committee finds that including this information is not helpful and distracts from the assessment of what is currently being done to identify and retrieve relevant scientific literature.

VBA Claims Data

The document indicates that claims data will be reviewed for trends, such as claim rate, grant rate, and service connection prevalence, and analysis of differences in deployed and nondeployed or other cohort characteristics and “may be used to assist in the development of a presumption when the science is at equipoise.” VBA claims data may also be used to inform which conditions should be reviewed. The committee interprets this description as indicating two uses for the data: (1) to identify trends in claims data that may be used to find conditions for possible presumptions (section 3.b: Data gathering, which appears to correspond to Figure 4-1 box A, item 2 and/or box B, item 2); and (2) claims data (claims rate, grant rate, and service connection prevalence) that can be used to inform a presumption recommendation. The first use is discussed earlier as part of the planning and preparatory phase, where the lack of detail on how claims data will be used in condition selection was noted.

The committee finds the presumption decision process document contains insufficient detail on the use of VBA claims data to inform the

evaluation process and conclusions regarding the strength or applicability of the evidence for a presumption. As with VA health data, the committee notes that only medical conditions for which veterans have filed claims will be captured in the VBA claims data.

Other Factors

This short section states that additional factors will be reviewed, such as deployments to combat zones, morbidity, and rarity of the conditions. It also states that other factors to be reviewed include the quantity and quality of the available science and data and the feasibility of producing future, methodologically sound scientific studies, although the committee considers this to be part of the review of the scientific literature, which would also involve identifying evidence gaps.

As with the previous subsections, the committee finds that information is insufficient on what these factors are or how they are to be incorporated into the assessment for it to comment on this content. It is unclear how these other factors would be used in VA’s scientific review process for either condition selection or standardized evaluation of the science (see Figure 4-1 box A, item 1 [e.g., DoD exposure data] and box B, item 5). Furthermore, the very broad call for a review of the feasibility of future studies seems out of place, and evidence gaps and studies to address them would typically be conducted as part of the review of the scientific literature.

Rare Conditions

Rare conditions (section 6E), which is one of the longer sections, focuses only on cancer and refers to “additional standards or an alternative process to evaluate the available evidence regarding such rare conditions” without providing additional detail or references for what those standards or processes might be. This section gives a long description of several topics, but only rare cancers are used as an example of how VA might deal with conditions with a low incidence in veterans, which VA defines (and as used by the American Cancer Society and the National Institutes of Health) as having an annual incidence rate of fewer than 6 cases per 100,000 individuals in the U.S. population. Other topics include a brief mention of developing guiding principles for evaluating rare conditions and the use of VA health and claims data to look for trends in medical conditions. The committee notes that it may be more difficult to find convincing evidence of a lack of an association when a disease is rare rather than convincing evidence of a true association. The discussion of the Bradford Hill factors

(see also Appendix A in the presumption decision process document) does not seem specific to assessing rare conditions and appears out of place in this subsection. It is not clear to the committee if the intention is to take a differential approach to identifying or evaluating data for rare conditions. This section also references the need for additional standards or an alternate process for evaluating the evidence for rare conditions but again offers no indication of what those additional standards or processes might be.

Although section 6 lists five data types (health care data, scientific literature, VBA claims data, other factors, and rare conditions) that aid in understanding the data types (components) that serve as input to the review, the methods and processes used to evaluate them are not provided. To be consistent with best scientific practices and standards, descriptions of these data types, how they would be used in the assessment, and the methods for their capture—including specifying to which aspect of the assessment each type would apply—would be included in the protocol developed to address the research question. Data types might also include extant evidence syntheses such as systematic reviews, meta-analyses, National Academies consensus reports, or scoping reviews.

The committee finds that, depending on their publication date, existing data sources may need to be updated but could provide a basis for further evidence identification and review.

The committee concludes that leveraging existing reviews could obviate the need to start from scratch in identifying the available scientific literature for a condition.

In Figure 4-1, box D, “Steps for Topic,” includes a literature search with MeSH nomenclature, screening studies for inclusion, and selection of reviewers, but no details are provided for any of these steps. Using best scientific practices, a protocol would be developed that describes a search strategy (databases, syntax), based on the research question(s), and lists inclusion and exclusion criteria for the searches, as well as the eligibility criteria to be applied during the selection process (i.e., screening of the literature). This protocol would then be implemented for the assessment. VA informed the committee that an information scientist has been hired by VA Health Outcomes Military Exposures (VA, 2023a); this type of expertise is often critical for designing and implementing a search strategy to systematically identify and select evidence efficiently and comprehensively.

The committee observes that a literature search is also conducted as part of the Preparatory Phase in box A, item 1, which says that there will be literature reviews of “relevant human, animal, mechanistic, and toxicological studies” for the list of medical conditions to be evaluated. The

committee expects that such a search would be updated for any condition that undergoes a standardized evaluation in section 7 and box D.

The committee finds that the standardized assessment process that VA has described in the presumption decision process document does not identify or describe general methods, processes, or tools for identifying and selecting the evidence for a condition.

Extraction of Key Data Elements from Evidence Sources

In section 7B of the presumption decision process document, VA acknowledges the importance of extracting data from available sources of evidence, including both internal (VHA health data and VBA claims data) and external (such as published literature) sources. Although VA indicates that the information “will be abstracted using a standardized review process,” there is a lack of clarity regarding what that process is, how extraction would “be performed in parallel with the PECOTS framework” (see Figure 4-3), and how this would expedite the evaluation as stated in the VA presumption decision process document.

VA states that data extractors can use templates to identify key data elements and gives some examples of what those elements might be. Including such a template in a final presumption decision process document or specific reference to one would be helpful to show how data elements might be abstracted. VA also notes that artificial intelligence strategies may expedite data extraction, but the committee cautions that such methods are not yet well developed and have not been validated for this step—particularly for data and studies related to environmental health, occupational health, or toxicology.

Appraisal of Individual Studies

Section 7 of the VA presumption decision process document, which outlines the standardized evaluation process to be used, does not explain if or how individual studies will be appraised for validity and reliability, which is needed to be consistent with scientific best practices. The critical appraisal approach would typically be described in a protocol and applied during a standardized assessment. This is an important area for additional detail, given that the description of determination of levels of evidence (section 7C) indicates that bias will be considered for the body of evidence, but it is not clear how this can be done if bias is not evaluated for individual studies. “Bias” is a general term for a systematic, nonrandom distortion of the measure of association, compromising the accuracy in estimation. Several types of biases exist, and each type may affect the estimate differently.

In environmental health reviews involving observational studies in humans, biases in confounding, exposure, and condition assessment are often of particular importance. In environmental health, risk of bias has been applied to both epidemiologic studies and in vivo studies, although it is not typical for in vitro studies. Many tools exist for evaluating the types of evidence that VA wishes to review, including risk of bias tools (e.g., NTP, the Navigation Guide,3 or ROBINS-E4). For example, the NTP risk of bias tool (NTP, 2019) includes evaluation of selection (randomization, allocation, comparison groups), confounding, performance (experimental conditions, blinding), attrition/exclusion, detection (exposure characterization, health outcome [condition] assessment), and selective reporting bias.

The following six characteristics have been considered in other National Academies reports as key factors to consider in the review of epidemiologic studies of exposures and health conditions in service member and veteran populations (NASEM, 2016, 2018, 2020a,b, 2022):

- A sufficient sample size for precise estimation (estimates that have minimal sampling variability) of causal effects,

- A representative sample of the population of interest,

- Identification of an appropriate comparison population,

- An exposure assessment of adequate quality,

- A health outcome assessment of adequate quality, and

- Identification of other contributing factors (that might be related to the exposure and the condition that would distort their relationship).

The first characteristic addresses random error or chance variation; however, with regard to the presumption decision process, estimate precision may be less important because in a veteran-centric process, it may not be necessary to know that a rare medical condition (for example) is problematic and should be considered for presumption. The second concerns selection bias; the third deals with confounding and selection bias; the fourth and fifth consider measurement error and misclassification, respectively; and the sixth addresses confounding (NASEM, 2022, p. 138). These characteristics are not intended to serve as a checklist or scorecard but rather are considerations that are most applicable for etiologic research on health effects of exposures to a particular hazard or hazards encountered during military

___________________

3 “The Navigation Guide methodology is a systematic and rigorous approach to research synthesis that has been developed to reduce bias and maximize transparency in the evaluation of environmental health information” (Woodruff and Sutton, 2014).

4 ROBINS-E (Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies–of Exposures) is a tool used primarily for systematic reviews that provides a structured approach to assessing the risk of bias in observational epidemiologic studies (ROBINS-E Development Group, 2023).

service. The committee considered conducting a detailed review of the criteria to be applied in evaluating each of these characteristics or summarizing well-established and more recently developed methodologic approaches to addressing these challenges to be beyond its Statement of Task and refers VA to approaches used by EFSA, EPA, NTP, and WHO for demonstrations in the evaluation of validity and reliability in environmental health studies.

Other critical appraisal tools more commonly applied to experimental animal studies or in vitro studies, such as the Klimisch categorization (Klimisch et al., 1997), SciRAP (Beronius et al., 2018; Roth et al., 2021), and SYRCLE (Hooijmans et al., 2014), may also be appropriate and would be consistent with scientific best practices depending on the scope and approach for the given assessment. Additionally, aspects of relevance, as evaluated by construct or external validity, may be important to appraise in individual studies depending on the research question and available evidence base.

Determination of Levels of Evidence

Scientific best practices involve a structured process of extracting information and determining levels of evidence. That process typically includes assessing the quality of individual studies, rating the confidence or certainty in the body of evidence, and translating the confidence or certainty ratings into evidence of health effects (NTP, 2019; Rooney et al., 2014). The VA standardized assessment process is presented in section 7 and shown in its PECOTS schematic (Figure 4-3) and the flow diagram (Figure 4-1) in the presumption decision process document. VA does not identify or describe steps or methods for data synthesis or integration (Box D, item 6 of Figure 4-1). Synthesis is required to characterize and summarize available evidence and may involve both qualitative and quantitative techniques. Integration is regularly used in evidence-based assessments in environmental health research, where evidence is integrated within and/or across streams (human, animal, mechanistic) to develop conclusions—often using a qualitative, weight-of-evidence approach. Assessing confidence in the evidence is also important; it often depends on the research question and type of evidence being evaluated. The methods for these collective steps in evaluating a body of evidence would typically be described in a protocol and applied during a standardized assessment.

The committee limited its discussion of VA’s assessment process, including the use of GRADE, to the information given in the presumption decision process document. Section 7C of the VA presumption decision process document indicates that VA uses a “semi-quantitative approach” to evaluate the quality of evidence and determine the levels of evidence based on the GRADE structure. VA does not explain what it means by

a “semi-quantitative approach” and how that relates to its proposed use of PECOTS and GRADE for evidence assessment. The committee stresses that PECOTS, GRADE, and other such tools are not algorithmic. Each tool has various domains and dimensions and inherent characteristics that should be considered and weighted with relative proportionality if and when assembling and assimilating these factors into a representatively relational “chain” that establishes and strengthens the probability of a positive association. Taking these in turn, it is critical to consider factors of each domain and dimension on the basis of their constituent strengths and limitations, as detailed in the following paragraphs.

The VA presumption decision process document does not explain how subject matter experts will use GRADE to assign certainty ratings to the evidence. GRADE is a tool used to grade the quality or certainty of evidence and make a determination about the strength of recommendations (Guyatt et al., 2011). It was developed and has been in use for decades primarily in the clinical research setting. Section 7C of the presumption decision process document states that GRADE “considers factors that diminish (e.g., bias, imprecision) and enhance (e.g., large effect, dose–response) the overall quality of evidence.” Applying GRADE to environmental and occupational health questions is a relatively new concept and practice. Although possible, it often necessitates modifications to incorporate the types of studies and data under evaluation, such as observational studies (Guyatt et al., 2011; NTP, 2019; Rooney et al., 2014; Woodruff and Sutton, 2011). The committee notes that the use of a structured process to assess confidence in the body of evidence need not be limited to the GRADE method, recognizing that GRADE may not fully address aspects important to VA for environmental health assessments such as different evidence streams including mechanistic studies and claims data.

Several organizations have developed approaches to incorporate the findings of a body of evidence and confidence in it as part of developing conclusions. For example, NTP’s Integrative Health Assessment Branch (previously the Office of Health Assessment and Translation) proposed its own approach to using GRADE in its evaluations to assess associations between environmental exposures and noncancer health effects (NTP, 2019). The WHO (2021) guidance is also informative on such aspects. These approaches may be more helpful than simply relying on the Bradford Hill factors (discussed in Chapter 2). However, when evaluating the body of evidence, the following considerations of those factors may be important:

- Adequacy of tools and techniques for evaluating human biologic activity (this may include a discussion of existing limitations and constraints that serve to demonstrate that any and all investigations have used the best available science and that the scientific model

- is still applicable given the absence of more precise tools and/or methods of evaluation; this is particularly true for mental health conditions).5

- Consistency (reproducibility) such that different persons in different places should exhibit relatively consistent manifestations of a condition.

- Biologic gradient where greater exposures generally lead to greater incidence and/or severity of effect. However, gradient effects can be directly or inversely proportional. This refers to a dose–response relationship, in which small doses (or minimal exposure) to an agent may yield substantive effects in particular individuals (as a consequence of genotype or phenotype); or ecologic variables (such as environmental factors) can increase or decrease the effect of the agent and affect the biologic—and psychologic—constitution and functions and therefore the susceptibility of each individual.

- Coherence—that is, the alignment of epidemiologic and laboratory findings, such that the greater the coherence (e.g., alignment, similarity, identicality), the greater the likelihood of effect (this is particularly true if laboratory methods accurately represent real-world effects).

Evidence to Recommendation

Section 5 of the VA presumption decision process document describes the standards for equipoise:

- Sufficient: the evidence is sufficient to conclude that an association exists.

- Equipoise and Above: the evidence is sufficient to conclude that an association is at least as likely as not but not sufficient to conclude that an association exists.

- Below Equipoise: the evidence is not sufficient to conclude that an association is at least as likely as not or is not sufficient to make a scientifically informed judgment.

- Against: the evidence suggests the lack of an association.

___________________

5 Given the importance of mental health issues and diagnoses in U.S. health systems, including VA, addressing this growing health issue may require adopting and testing new, more complex models. The traditional medical model is generally unsatisfactory for understanding mental health disorders and conditions such as fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue, and other functional disorders. In these instances, the presumption decision process may use models that acknowledge the complexity of clinical phenomena and their connection to biologic, environmental, psychologic, and social elements.

The committee notes that these standards are listed in the PACT Act and are not the same categories of association—that is, sufficient evidence of an association, limited or suggestive evidence of an association, inadequate or insufficient evidence of an association, and limited or suggestive evidence of no association—as those used by National Academies reports to examine the relationships between military exposures and health conditions. Similarly, the GRADE methodology category of “insufficient evidence to recommend for or against” is also not appropriate for determining “equipoise.” The methods used for determining the strength of evidence as described in section 7C “Determination of Levels of Evidence” in the presumption decision process document are distinct from the methods for using the identified evidence to determine the strength of association and assigning a standard of equipoise.

The VA presumption decision process document describes the statutory requirement that the strength of evidence for or against a positive association be defined as specific categories related to equipoise. This section describes how the underlying scientific data will be used to decide equipoise, representing the last step in the scientific process, which essentially results in a conclusion leading to a presumption recommendation based on the available body of evidence.

The VA presumption decision process uses “equipoise” to denote a threshold for a presumption in which the probability of a positive association is judged to be as equally likely as not, equivalent to a probability of exactly 50%. This threshold is grounded in law and reflected in the desired attributes of the VA presumption decision process noted in Chapter 2, including being veteran centric and responsive to veterans’ needs. VA states that in a situation where the evidence is exactly at equipoise, the benefit of the presumption would be recommended (VA, 2023a). The committee notes that the standards for “equipoise” only refer to the probability of an association, and the assignment of an equipoise standard or category is much more nuanced and semi-subjective. The process as given in the presumption decision process document assumes that rational subject matter experts, when faced with the same body of evidence, will all come to the same judgment. However, this consensus will not necessarily be true if, for example, the experts differ in their background beliefs about relevant scientific theories, mechanisms of action, biologic plausibility, or causal relationships, or because their assessments of the relative harms associated with different types of error differ. Therefore, the lack of information or criteria for how the “standard” for an association (that is, as likely as not) is to be operationalized and applied to produce a presumption recommendation is a notable shortcoming. Having such criteria would serve as boundaries to limit the uncertainty that different panels of experts would come to different conclusions regarding the probability of an association. Once criteria to

operationalize the application of an equipoise standard are made, VA will need to test them to ensure they are appropriate since no validated method for this application exists. The presumption decision process document does not indicate whether the conclusion and subsequent presumption recommendation made by the condition-specific review panel require consensus or how dissent is addressed.

The committee notes that “equipoise” is used in clinical research to refer to a situation where there is uncertainty or conflicting expert opinion about the relative merits of two or more interventions rather than a perfect balance of opinions. To compare the merits of different interventions (to tip the scale of equipoise), a patient may be randomized in a clinical trial to receive one of the interventions as long as it does not appear that an alternative intervention would be more advantageous to a particular patient (London, 2017). This is not the same use of equipoise as operationalized by the PACT Act and the VA presumption decision process document. The evaluation of the evidence hinges on whether a condition can be assigned to one of the legislatively defined association standards (i.e., sufficient, equipoise and above, below equipoise, and against) with sufficient confidence that a more extensive analysis would be unlikely to change the assigned standard. As noted, no requirement exists regarding the magnitude of the association or, equivalently, for the fraction of cases of the condition that are attributable to the exposure, a determination of the probability of a positive association. Likewise, as there may be several causes or findings of association for a specific condition, a decision of presumption may not distinguish between specific exposures as long as they are likely tied to military service.

The committee finds a lack of information on how the “standard” for an association (that is, as likely as not) is to be operationalized and applied to produce a presumption recommendation for a condition.

The committee concludes that the term “equipoise” denotes a lack of consensus across the medical community and that the term as required by law to be used in the presumption decision process is inconsistent with the current scientific use.

Findings, Conclusions, and Recommendations for Conducting a Standardized Evaluation of the Science

With regard to the conduct of a standardized evaluation of scientific and other evidence used to make a recommendation on whether a condition should have a presumption of service connection, the committee has the following findings, conclusions, and recommendations:

The committee finds that it is unable to judge whether the pre-decisional VA presumption decision process document and the activities in individual steps in the process align with scientific best practices. Moreover, it is not able to comment on the fairness or consistency of the process primarily due to the organization of the VA presumption decision process document, the lack of detail on how the process will be operationalized, and the lack of specifics for each step in the process, such as the lack of criteria on how the evidence will be extracted and reviewed and individual studies will be appraised for validity and reliability.

Furthermore, the committee finds an inconsistent correspondence between the four sections (sections 3, 5, 6, and 7) in the VA presumption decision process document that pertain to scientific aspects of the process and in the steps in the presumption decision process flow diagram (Figure 4-1) included in that document.

The committee concludes that the overall usefulness of the presumption decision process document could be improved by enhancing the existing description of the evaluation process, including details on how each step will be operationalized, providing a logical one-to-one correspondence between the text and the flow diagram, and incorporating scientific best practices, by either including additional details in the VA presumption decision process document or referencing other documentation.

Recommendation 4-1: The committee recommends that VA’s presumption decision process contain sufficient detail to define how it will operationalize each step of the scientific process, either in the presumption decision process document or by reference to other documentation, beginning with condition identification and selection, through evidence review to the application of a standard on the likelihood of a positive association.

Recommendation 4-2: The committee recommends that VA model its scientific evaluation of the environmental health evidence using existing standardized and structured approaches. Such a standardized evaluation process should include a formal problem assessment and study planning phase; development of a protocol that addresses the structured research question (e.g., PECOTS) and includes a detailed literature search strategy and inclusion/exclusion criteria; and a report that presents the systematic identification and selection of evidence, critical appraisal of the validity and reliability of studies, synthesis and integration of a body of evidence, and a structured approach to determining conclusions (levels of evidence) about the scientific evidence.

Recommendation 4-3: The committee recommends that VA use existing frameworks, tools, and approaches designed for environmental health assessments (e.g., NTP; World Health Organization Framework on the use of systematic review in chemical risk assessment) and apply or adapt them in a manner that aligns with scientific best practices.

REFERENCES

Beronius, A., L. Molander, J. Zilliacus, C. Rudén, and A. Hanberg. 2018. Testing and refining the Science in Risk Assessment and Policy (SciRAP) web-based platform for evaluating the reliability and relevance of in vivo toxicity studies. The Journal of Applied Toxicology 38:1460–1470.

EFSA (European Food Safety Authority). 2010. Application of systematic review methodology to food and feed safety assessments to support decision making: EFSA guidance for those carrying out systematic reviews. EFSA Journal 8(6):1637. https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2010.1637.

EPA (Environmental Protection Agency). 2022. Draft protocol for systematic review in TSCA evaluations. https://www.epa.gov/assessing-and-managing-chemicals-under-tsca/draft-protocol-systematic-review-tsca-risk-evaluations (accessed May 31, 2023).

Federal Register. 2021. Rule: Department of Veterans Affairs—presumptive service connection for respiratory conditions due to exposure to particulate matter. Federal Register 86(148):42724–42733.

Garritty, G. C., C. Hamel, M. Hersi, C. Butler, Z. Monfaredi, A. Stevens, B. Nussbaumer-Streit, W. Cheng, and D. Moher. 2020. Assessing how information is packaged in rapid reviews for policy-makers and other stakeholders: A cross-sectional study. Health Research Policy and Systems 18(112). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-020-00624-7.

Garritty, C., G. Gartlehner, B. Nussbaumer-Streit, V. J. King, C. Hamel, C. Kamel, L. Affengruber, and A. Stevens. 2021. Cochrane Rapid Reviews Methods Group offers evidence-informed guidance to conduct rapid reviews. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 130:13–22.

Guyatt, G. H., A. D. Oxman, H. J. Schunemann, P. Tugwell, and A. Knottnerus. 2011. GRADE guidelines: A new series of articles in the Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 64:380–382.

Higgins, J. P. T., J. Thomas, J. Chandler, M. Cumpston, T. Li, M. J. Page, and V. A. Welch, editors. 2022. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions, version 6.3. https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current (accessed June 29, 2023).

Hooijmans, C. R., M. M. Rovers, R. B. de Vries, M. Leenars, M. Ritskes-Hoitinga, and M. W. Langendam. 2014. SYRCLE’s risk of bias tool for animal studies. BMC Medical Research Methodology 14:43.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2011. Finding what works in health care: Standards for systematic reviews. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Klimisch, H. J., M. Andreae, and U. Tillmann. 1997. A systematic approach for evaluating the quality of experimental toxicological and ecotoxicological data. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology 25(1):1–5.

London, A. J. 2017. Equipoise in research: Integrating ethics and science in human research. JAMA 317(5):525–526.

Morgan, R. L., P. Whaley, K. A. Thayer, and H. J. Schunemann. 2018. Identifying the PECO: A framework for formulating good questions to explore the association of environmental and other exposures with health outcomes. Environment International 121 (Pt1):1027–1031.

Munn, Z., M. D. J. Peters, C. Stern, C. Tufanaru, A. McArthur, and E. Aromataris. 2018. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology 18(1):143. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x.

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2016. Gulf War and health: Volume 10: Update of health effects of serving in the Gulf War (2016). Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NASEM. 2018. Veterans and Agent Orange: Update 11 (2018). Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NASEM. 2020a. Assessment of long-term health effects of antimalarial drugs when used for prophylaxis. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NASEM. 2020b. Respiratory health effects of airborne hazards exposures in the Southwest Asia theater of military operations. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NASEM. 2022. Reassessment of the Department of Veterans Affairs airborne hazards and open burn pit registry. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NTP (National Toxicology Program). 2019. Handbook for conducting a literature-based health assessment using OHAT approach for systematic review and evidence integration. https://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/sites/default/files/ntp/ohat/pubs/handbookmarch2019_508 (accessed April 12, 2023).

Page, M. J., J. E. McKenzie, P. M. Bossuyt, I. Boutron, T. C. Hoffmann, C. D. Mulrow, L. Shamseer, J. M. Tetzlaff, E. A. Akl, S. E. Brennan, R. Chou, J. Glanville, J. M. Grimshaw, A. Hróbjartsson, M. M. Lalu, T. Li, E. W. Loder, E. Mayo-Wilson, S. McDonald, L. A. McGuinness, L. A. Stewart, J. Thomas, A. C. Tricco, V. A. Welch, P. Whiting, and D. Moher. 2021. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews 10:89.

Perry, R., A. Whitmarsh, V. Leach, and P. Davies. 2021. A comparison of two assessment tools used in overviews of systematic reviews: ROBIS versus AMSTAR-2. Systematic Review 10:273. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01819-x.

Peters, M. D. J., C. M. Godfrey, K. Hanan, P. McInerney, D. Parker, and C. B. Soares. 2015. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare 13(3):141–146.

ROBINS-E Development Group (J. Higgins, R. Morgan, A. Rooney, K. Taylor, K. Thayer, R. Silva, C. Lemeris, A. Akl, W. Arroyave, T. Bateson, N. Berkman, P. Demers, F. Forastiere, B. Glenn, A. Hróbjartsson, E. Kirrane, J. LaKind, T. Luben, R. Lunn, A. McAleenan, L. McGuinness, J. Meerpohl, S. Mehta, R. Nachman, J. Obbagy, A. O’Connor, E. Radke, J. Savović, M. Schubauer-Berigan, P. Schwingl, H. Schunemann, B. Shea, K. Steenland, T. Stewart, K. Straif, K. Tilling, V. Verbeek, R. Vermeulen, M. Viswanathan, S. Zahm, and J. Sterne). 2023. Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies - of Exposure (ROBINS-E). Launch version. https://www.riskofbias.info/welcome/robins-e-tool (accessed June 21, 2023).

Rooney, A. A., A. L. Boyles, M. S. Wolfe, J. R. Bucher, and K. A. Thayer. 2014. Systematic review and evidence integration for literature-based environmental health science assessments. Environmental Health Perspectives 122(7):711–718.

Roth, N., J. Zilliacus, and A. Beronius. 2021. Development of the SciRAP approach for evaluating the reliability and relevance of in vitro toxicity data. Frontiers of Toxicology 3:746430. https://doi.org/10.3389/ftox.2021.746430.

Sheard, D., and S. Steeves. 2018. Evidence-based publication planning: Mapping the literature. https://ismpp-newsletter.com/2018/08/29/evidence-based-publication-planning-mapping-the-literature/ (accessed May 31, 2023).

Tricco, A. C., and K. Oboirien. 2017. Scoping reviews: What they are and how you can do them. Cochrane Training. https://training.cochrane.org/resource/scoping-reviews-what-they-are-and-how-you-can-do-them (accessed May 9, 2023).

Tricco, A. C., E. V. Langlois, and S. E. Straus, editors. 2017. Rapid reviews to strengthen health policy and systems: A practical guide. Geneva: World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/258698/9789241512763-eng.pdf (accessed June 29, 2023).

VA (Department of Veterans Affairs). 2023a. Charge to the Committee to Review the Department of Veterans Affairs Presumption Decision Process. Presentation by Dr. Patricia Hastings, Chief Consultant, Health Outcomes Military Exposures, March 7, 2023. Available from the project public access file at https://www8.nationalacademies.org/pa/managerequest.aspx?key=HMD-BPH-22-10.

VA. 2023b. Response to the Committee to Review the Department of Veterans Affairs Presumption Decision Process information and data request. Provided by Dr. Patricia Hastings, Chief Consultant, Health Outcomes Military Exposures, VA, March 10, 2023. Available from the project public access file at https://www8.nationalacademies.org/pa/managerequest.aspx?key=HMD-BPH-22-10.

VA. 2023c. Response to the Committee to Review the Department of Veterans Affairs Presumption Decision Process information and data request. Provided by Dr. Patricia Hastings, Chief Consultant, Health Outcomes Military Exposures, VA, April 19, 2023. Available from the project public access file at https://www8.nationalacademies.org/pa/managerequest.aspx?key=HMD-BPH-22-10.

WHO (World Health Organization). 2021. Framework for the use of systematic review in chemical risk assessment. Geneva: World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240034488 (accessed April 12, 2023).

Woodruff, T. J., and P. Sutton. 2011. An evidence-based medicine methodology to bridge the gap between clinical and environmental health sciences. Health Affairs 30(5):931–937.

Woodruff, T. J., and P. Sutton. 2014. The Navigation Guide systematic review methodology: A rigorous and transparent method for translating environmental health science into better health outcomes. Environmental Health Perspectives 122(10):1007–1014.