Review of the Department of Veterans Affairs Presumption Decision Process (2023)

Chapter: 1 Background and Policy Context

1

Background and Policy Context

The United States has a long history of recognizing and honoring the service and sacrifices of its veterans. Those sacrifices may include injury and illness resulting from military service, whether that occurs during service or develops at a later date. These injuries and illnesses are called “service-connected conditions,” and veterans who have a diagnosed disability as a result of this service connection are owed proper health care and compensation. The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) uses “condition” to refer to any adverse human health outcome, including a mental health condition, and the committee adopts VA’s terminology throughout the report. For some medical conditions that develop after or are exacerbated by military service, the scientific information needed to link them to service may be incomplete. If so, Congress or VA may need to make a “presumption” of service connection so that an individual or group of veterans can be appropriately compensated. Since 1921, Congress and VA have granted numerous presumptions to diagnosed service-connected injuries and illnesses so that veterans may receive health care and disability compensation (CRS, 2014). In fiscal year 2022 alone, VA is estimated to have disbursed an estimated $120.7 billion in compensation to 5.9 million veterans (VA, 2022a). Although an exact amount is not available, the aggregate cost of compensation for service-connected disability benefits since 1921 is trillions of dollars.

The Sergeant First Class Heath Robinson Honoring Our Promise to Address Comprehensive Toxics Act (PACT Act) of 2022 statutorily recognizes the long-term cost of war by adding several presumptive conditions and requirements for the process for how conditions for presumption are

considered. The breadth and financial impact of the PACT Act is large; it obligates the federal government to trillions of dollars of federal expenditures for service-connected disabilities. Unlike VA health care, which is discretionary federal spending, service-connected disabilities are mandatory federal expenditures (i.e., entitlements). As the PACT Act was in the process of becoming law, VA was working in parallel to expedite and make more efficient the presumption decision process. In June 2022, VA released an eight-page pre-decisional document of its revised presumption decision process. PACT Act Section 202 §1176 calls for a review of that document by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (the National Academies).

This chapter provides an introduction to VA, a history of presumption decision making, the role that the National Academies has played in the process, and the requirements of the PACT Act regarding the current process. This chapter also presents the committee’s Statement of Task and general approach to addressing it. An annex to the chapter reproduces verbatim VA’s eight-page pre-decisional presumption decision process document that the committee was asked to review; however, given the format size of this report, the pages of the pre-decisional document as reproduced do not exactly align with the original document.

DEFINING PRESUMPTION

The mission of VA is to honor and care for those who have served in the armed forces and their families. Veterans who have incurred a disability due to their military service receive benefits from VA, including health care and service-connected disability compensation. The latter is a tax-free benefit paid for a disability that arose during service, was worsened or aggravated during service, or is presumed by VA to be related to service (VA, 2023b).

VA is organized into three administrations, the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), the Veterans Benefits Administration (VBA), and the National Cemetery Administration. Two of these, VHA and VBA, are involved in service-connected disability compensation. VHA manages the health care system that provides services such as hospital, outpatient medical, dental, and prosthetics; residential care; readjustment counseling; homeless veteran programs; alcohol and drug dependency treatment; and medical evaluations for disorders related to service or environmental hazards (VA, 2015a). As of 2023, VHA provides care at 1,298 health care facilities, including 171 medical centers and 1,113 outpatient sites, and serves 9 million enrolled veterans each year (VA, 2023c). Through VHA, veterans who are diagnosed with a service-connected condition, including disability, may receive care for that condition and use that diagnosis to file for compensation.

VBA provides benefits, including pensions and dependent compensation, life insurance programs, education service, home loans, employment service, and service-connected disability compensation to veterans, service members, and their families who meet certain criteria. A veteran or service member must have a current condition (illness or injury called a “disability”) that affects the mind or body and the individual must have served on active duty, active duty for training, or inactive duty training. Additionally, one of the following criteria must be met: the individual became sick or injured while serving in the military and can link this condition to the illness or injury (an “in-service disability claim”); they had an illness or injury before they joined the military, and service worsened the condition (a “preservice disability claim”); or they have a disability (physical or mental) related to active-duty service that did not appear until after service ended (a “post-service disability claim”) (VA, 2023a). VBA has ratings for the severity of the disability that affect the compensation rates, meaning that not every veteran will receive the same amount for the same disability. VA determines disability severity based on the evidence, which can come from a number of sources, including a veteran’s claim, health care providers, government agencies, and military records.

A disability rating is assigned on the basis of the severity of the service-connected condition, and a veteran may have more than one rating. A disability rating is expressed as a percentage (in 10% increments) of the extent to which the disability decreases their overall health and ability to function (VA, 2019).

Establishing a connection between military service and a disability (mental or physical) can be difficult for a number of reasons, including lack of documentation on the exposures encountered during service, the lag time between an exposure and the manifestation of the disability, and the lack of scientific evidence to link or make an association between a specific exposure and a particular disability. In some cases, VA “presumes that specific disabilities diagnosed in certain veterans were caused by exposures during military service or by their service” (VA, 2020). VA has established a number of presumptive conditions specific to veterans who are of a particular era or who served in a particular location (VA, 2020).

There are two types of presumptive disability connections: service and exposure. The first is presumption of service connection, which means that a certain condition is considered to have been incurred during or aggravated by service if it manifests within the time frame specified for that condition under regulation or statute, even with no evidence of such condition during service. For example, service-connected presumptions may be applied to chronic conditions, such as hypertension or diabetes, for veterans who served in Vietnam or surrounding countries and waterways for specific periods. Such a presumption may also be applied for other health

conditions, including mental health conditions, such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The second type of connection is presumption of exposure, which means that a veteran is presumed to have been exposed based on service at a particular location and during a specific period, as stipulated in regulation or statute. For example, VA has established presumption of exposure for three chronic respiratory health conditions (asthma, rhinitis, and sinusitis, to include rhinosinusitis) in association with presumed exposures to fine particulate matter. This presumption applies to veterans who served on active military, naval, or air service in the Southwest Asia theater of operations during the 1990–1991 Gulf War and post-9/11 operations or in Afghanistan, Syria, Djibouti, or Uzbekistan on or after September 19, 2001.

If a veteran is a member of a specific group, defined by dates and locations of service, and has a diagnosed disability that has been determined to be service connected, then the veteran may be entitled to compensation and associated medical care without having to prove that the disability was the result of their military service; that is, the veteran no longer has the burden of proof. Several groups of veterans have been identified as eligible for specific presumptions, including atomic (those exposed to radiation during the development and testing of atomic bombs during World War II), Vietnam, and Gulf War veterans. Members of the latter group, which includes veterans of both the 1990–1991 Gulf War and the post-9/11 conflicts, may have served in the same locations but at different periods, leading to different presumptions.1

As of 2021, the last year for which data are publicly available, approximately 5.9 million veterans were receiving disability benefits (VA, 2022a), of whom more than 2 million were rated as being 70% or more disabled (VA, 2021). Compensation is based on the disability rating but also on external factors, such as the number of dependents or evidence of two or more disabilities (Christensen et al., 2007).

HISTORY OF SERVICE-CONNECTED DISABILITY DECISIONS

Congress first established a presumption of service connection in 1921 when it amended the War Risk Insurance Act (PL 63-193) to provide veterans with a service connection for tuberculosis and neuropsychiatric disease “occurring within two years of separation from active duty military

___________________

1 These operations include Operation Desert Shield (August 7, 1990–January 17, 1991), Operation Desert Storm (January 17, 1991–February 28, 1991), Operation Enduring Freedom (October 7, 2001–December 28, 2014), Operation Iraqi Freedom (March 20, 2003–August 31, 2010), Operation New Dawn (September 1, 2010–December 15, 2011), Combined Joint Task Force–Operation Inherent Resolve (October 17, 2014–present), and Operation Freedom’s Sentinel (January 1, 2015–August 31, 2021) (CRS, 2019; DoD, 2022a,b).

service” (CRS, 2014). Later that same year, the first list of chronic constitutional diseases was established; it included anemia, arteriosclerosis, beriberi, diabetes insipidus, diabetes mellitus, endocrinopathies, gout, hemochromatosis, hemoglobinuria (paroxysmal), hemophilia, Hodgkin’s disease, leukemia (all types), ochronosis, pellagra, polycythemia (erythremia), purpura, rickets, and scurvy (Veterans Administration, 1921). This list, later renamed “chronic diseases,” was periodically expanded by both Congress and VA between 1924 and 1948 to include such conditions as epilepsy and “organic diseases of the nervous system.” In 1945, a new presumptive category of tropical diseases was established, beginning with malaria.

The Bradley Commission conducted an extensive review of the VA disability process in 1956. It recommended that the existing presumptions for service connection be withdrawn, as it found that “there is otherwise in the law sufficient protection for the veteran to establish service connection of any and all diseases” (President’s Commission on Veterans’ Pensions, 1956, p. 178). It also commented that the process for determining presumptive conditions was “outdated and overly simplistic,” calling for stricter guidelines for rating conditions using updated medical knowledge and improving technology, which might allow for establishing a direct service connection rather than resorting to presumptions for many cases of disability. Although no action was taken on the commission’s recommendations, the advances and changes in medical care have remained relevant to making direct presumptions, as the commission indicated.

In 1961, criteria for the presumptions in the chronic diseases and tropical diseases categories appeared (Federal Register, 1961). No new presumptions were created during this decade. In the 1970s, a new presumptive category, former prisoners of war (POWs), was established. PL 91-376 Section 3 specified that POWs from World War II, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War were service connected for a number of physical and mental health conditions. In 1979, ischemic heart disease and other cardiovascular disease were presumptively associated with service for amputation of one lower extremity at or above the knee or amputations of both lower extremities at or above the ankles (Federal Register, 1979).

In the 1980s, presumptions were expanded within the categories of POWs, herbicide agents, and radiation. In 1988, Congress passed PL 100-322, providing a 40-year presumptive period for a long list of cancers associated with nuclear testing.

Many new presumptions were established in the 1990s for exposure to herbicide agents, radiation, and mustard gas/lewisite; new presumptions were also established for POWs. In 1991, Congress passed the Agent Orange Act (PL 102-4) which added non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, soft-tissue sarcomas, and chloracne (or other acneform disease) to the presumptive category of herbicide agents. In 1993, PTSD was added to the list of

presumptive conditions for military service and former POWs (Federal Register, 1993). In 1994, compensation for Gulf War undiagnosed illnesses was proposed (Federal Register, 1994); the Compensation for Certain Undiagnosed Illnesses rule for Gulf War veterans was finalized in 1995, the first time that Congress had made a presumption for a list of medical terms (Federal Register, 1995). The Persian Gulf War Veterans Act of 1998 (PL 105-277) established service connection for medical conditions associated with exposure to biologic, chemical, or toxic agents; environmental or wartime hazards; or preventive medicines or vaccines associated with service in the Southwest Asia theater of operations during the 1990–1991 Gulf War.

In the 2000s, additional cancer presumptions for radiation exposure and new presumptions, including for Type 2 diabetes for tactical herbicide agent exposure, were added, and the list of presumptive diseases for POWs was expanded (Federal Register, 2001a). In 2001, clarifications for presumptive periods relating to Gulf War and Vietnam service were published (Federal Register, 2001b).

Veterans’ Disability Benefits Commission

In response to the post-9/11 conflicts, the Veterans’ Disability Benefits Commission was established in 2004 by the National Defense Authorization Act (PL 108-136). It conducted the first extensive and “comprehensive evaluation and assessment” of disability benefits since the 1956 Bradley Commission. In 2006, the commission requested that the Institute of Medicine2 conduct the assessment; the resulting report, Improving the Presumptive Disability Decision-Making Process for Veterans, was published in 2008 and is discussed in the next section. The commission requested that a contractor prepare a report “regarding the appropriateness of the current benefits program for compensating for loss of average earnings and degradation of quality of life resulting from service-connected disabilities for veterans. . . [and that] evaluated the impact of VA compensation for the economic well-being of survivors and assessed the quality of life of both service-disabled veterans and survivors” (Christensen et al., 2007, p. 1).

The commission reported its findings to the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Veterans’ Affairs in October 2007. It offered 113 recommendations, specifying 14 as high priority for adoption. Commission chair Lieutenant General James Terry Scott stated that “when there is evidence that a condition is experienced by a sufficient cohort of veterans, a presumption can be established so that it is presumed to be the result of

___________________

2 As of March 2016, the Health and Medicine Division of the National Academies continues the consensus studies and convening activities previously undertaken by the Institute of Medicine.

military service.” He also expressed the view that the 2008 National Academies report recommending a detailed, comprehensive, and transparent framework based on scientific principles would improve the presumption process (U.S. House of Representatives, 2007).

The Role of the National Academies

The National Academies has assisted VA with the presumption decision process in two ways: providing a review of and framework for improving the process and synthesizing information on the strength of the evidence of an association between numerous military exposures and health conditions. VA has used both of these activities to inform its determinations of presumptive service connections for a variety of exposures and health conditions.

Presumption Decision Process

The 2008 National Academies report Improving the Presumptive Disability Decision-Making Process for Veterans, requested by the Veterans’ Disability Benefits Commission and conducted under contract with VA, sought to improve the often decades-long process to establish a presumption for a service-connected health condition. The committee that produced the report was tasked with describing previous processes and making recommendations for an “improved scientific framework” for future determinations of establishing presumptions. That committee documented the process by developing case studies around exposures and health conditions for which presumptions had been made. The committee also reviewed general methods used to evaluate scientific evidence to determine causal associations between a specific exposure and a health condition. The report offered a number of recommendations to transform the presumption decision-making process that called for the following revisions:

- Have an open method for nominating exposures and conditions for review,

- Address stakeholder inclusiveness,

- Develop and maintain a system for tracking military exposures,

- Establish a mechanism for monitoring the health conditions of all military personnel while in service and after separation,

- Use a structured framework for evaluating scientific evidence regarding the relationship between a veteran’s exposure(s) and a health condition,

- Establish a consistent and transparent decision-making process, and

- Ensure an organizational structure to support the revised process (IOM, 2008).

Evidence Reviews

The National Academies has been conducting evidence reviews for VA for more than 30 years, including the Veterans and Agent Orange series and the Gulf War and Health series of reports that examine the scientific evidence on the relationship between military, particularly deployment, exposures and health conditions experienced during and after service. These evidence reviews have assisted VA in making decisions regarding presumptions for conditions and a variety of military exposures, particularly deployment exposures. The Gulf War and Health series used five categories of association: sufficient evidence of a causal relationship, sufficient evidence of an association, limited/suggestive evidence of an association, inadequate/insufficient evidence to determine an association, and limited/suggestive evidence of no association. The Veterans and Agent Orange series used the same categories but omitted the strongest category, sufficient evidence of a causal relationship. Other National Academies reports have also examined the relationship between military exposures and health effects, such as Assessment of Long-Term Health Effects of Antimalarial Drugs When Used for Prophylaxis (NASEM, 2020b), Blue Water Navy Vietnam Veterans and Agent Orange Exposure (IOM, 2011a), Contaminated Water Supplies at Camp Lejeune: Assessing Potential Health Effects (NRC, 2009), Long-term Health Consequences of Exposure to Burn Pits in Iraq and Afghanistan (IOM, 2011b), and Respiratory Health Effects of Airborne Hazards Exposures in the Southwest Asia Theater of Military Operations (NASEM, 2020a). Each report used the same or slightly modified categories of association as in the two series.

In 2020, the National Academies released Respiratory Health Effects of Airborne Hazards Exposures in the Southwest Asia Theater of Military Operations. It found limited or suggestive evidence of an association between fine particulate matter and respiratory symptoms and also examined the evidence for an association with 26 other respiratory conditions, including asthma and the development of asthma, rhinitis, and sinusitis, but concluded that the evidence was insufficient or inadequate for any of these conditions. VA cannot make presumptions based on symptoms; a diagnosed condition is required.3 Following the release of this report, VHA and VBA together conducted additional reviews of the published scientific literature of human and nonhuman studies and examined data from VA health care records (Federal Register, 2021). In 2021, VA issued an interim final rule to establish a presumptive service connection for three chronic respiratory health conditions—sinusitis, rhinitis, and newly diagnosed asthma—in association

___________________

3 Some veterans may receive disability compensation for chronic disabilities resulting from undiagnosed illnesses or medically unexplained chronic multi-symptom illnesses defined by a cluster of signs or symptoms, but these are associated with a diagnostic code (VA, 2015b).

with exposures to fine particulate matter (Federal Register, 2021). These presumptions applied to veterans who were on active-duty service in the Southwest Asia theater of operations or in Afghanistan, Syria, Djibouti, or Uzbekistan on or after September 19, 2001. To be eligible for VA benefits, a veteran must have been diagnosed with one of these three conditions within 10 years of their last qualifying period of service (Federal Register, 2021).

Although not based on any National Academies reports, on April 25, 2022, VA established another presumptive service connection for nine rare respiratory cancers (squamous cell carcinoma of the larynx, squamous cell carcinoma of the trachea, adenocarcinoma of the trachea, salivary gland-type tumors of the trachea, adenosquamous carcinoma of the lung, large cell carcinoma of the lung, salivary gland-type tumors of the lung, sarcomatoid carcinoma of the lung, and typical and atypical carcinoid of the lung) in association with exposure to fine particulate matter (Federal Register, 2022). This connection applies to veterans who served in the Southwest Asia theater of operations from August 2, 1990, to the present or in Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, Syria, or Djibouti from September 19, 2001, to the present (Federal Register, 2022).

STATEMENT OF TASK

On August 10, 2022, the PACT Act (PL 117-168) was signed into law. Section 202 § 1176 states that VA will enter into an agreement with the National Academies to conduct an assessment of VA’s implementation of its presumption decision process. The assessment is to include a determination of “(i) whether the process is in accordance with current scientific standards for assessing the link between exposure to environmental hazards and the development of health outcomes, (ii) assess whether the criteria are fair and consistent, and (iii) provide recommendations for improvements to the process.” The full legislative language requiring this assessment is in Appendix A. VA’s eight-page pre-decisional document of its updated presumption decision process is dated June 14, 2022, and formed the basis of the National Academies’ assessment. The committee’s Statement of Task is shown in Box 1-1.

COMMITTEE COMPOSITION AND APPROACH

The National Academies convened a committee comprising 10 members with expertise in decision science and causal decision making, systematic review methodologies, causal inference, environmental epidemiology, chronic disease epidemiology, mental health disorders, statistics, exposure assessment, health risk assessment, toxicology, bioethics, military and veterans’ health, and VA administrative processes (see Appendix C for

biographical sketches). The committee held three full meetings and several subgroup meetings between March and June 2023 to consider evidence and write its report. The meetings included an open session with presentations by VA representatives, professional staff of the congressional Senate and House Committees on Veterans’ Affairs, and others to elucidate the committee’s charge and describe relevant aspects of the VA presumption decision process (see Appendix B for the agenda and speakers for the public information-gathering session).

ORGANIZATION OF THE REPORT

VA’s eight-page pre-decisional presumption decision process document is reproduced verbatim as an annex to this chapter. As of the writing of this report, that pre-decisional document is not publicly available. Chapter 2 describes the committee’s approach and methods for responding to its Statement of Task, including its interpretation of the task, information gathering, and defining specific terms and characteristics for the VA presumption decision process. To best respond to its charge, the committee chose to group sections of the process rather than address sequential sections as they appear in the draft document. In Chapter 3, the committee examines the administrative and governance processes that include selection of conditions for review, composition of the review panels, and VA entities involved in the

process for final presumption decisions. In Chapter 4, the committee examines the scientific aspects of the presumption decision process. Chapters 3 and 4 also present conclusions and recommendations. Chapter 5 provides a synthesis of the common and overarching themes identified in the committee’s assessment of the governance and scientific aspects of the presumption decision process. This report includes three appendixes. Appendix A presents PL 117-168 Section 202 §1176, §1171, §1172, §1173, and §1174. Appendix B contains the open session agenda and presenters, and Appendix C provides the committee and staff biographical sketches.

REFERENCES

Christensen, E., J. McMahan, E. Schaefer, T. Jaditz, and D. Harris. 2007. Final Report for the Veterans’ Disability Benefits Commission: Compensation, Survey Results, and Selected Topics. https://www.cna.org/archive/CNA_Files/pdf/d0016570.a4.pdf (accessed April 20, 2023).

CRS (Congressional Research Service). 2014. Veterans Exposed to Agent Orange: Legislative History, Litigation, and Current Issues. https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/R43790.pdf (accessed April 13, 2023).

CRS. 2019. U.S Periods of War and Dates of Recent Conflicts. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/RS/RS21405/30 (accessed June 27, 2022).

DoD (Department of Defense). 2022a. Operation Inherent Resolve–One mission, many nations. https://www.inherentresolve.mil/About-CJTF-OIR/ (accessed June 23, 2023).

DoD. 2022b. Operation Freedom’s Sentinel, Operation Enduring Sentinel-Lead Inspector General Report to the United States Congress. https://media.defense.gov/2022/Feb/15/2002939389/-1/-1/1/LEAD%20INSPECTOR%20GENERAL%20FOR%20OPERATION%20FREEDOM%E2%80%99S%20SENTINEL%20AND%20OPERATION%20ENDURING%20SENTINEL%20OCTOBER%201,%202021%20%E2%80%93%20DECEMBER%2031,%202021.PDF (accessed June 23, 2023).

Federal Register. 1961. Disease subject to presumptive service connection. Federal Register 26(36):1581–1582.

Federal Register. 1979. Pension, compensation, and dependency and indemnity compensation, proximate results, secondary conditions. Federal Register 44(168):50339–50340.

Federal Register. 1993. Final rule: Direct service connection (post-traumatic stress disorder). Federal Register 58(95):29109–29110.

Federal Register. 1994. Compensation for certain undiagnosed illnesses. Proposed rule. Federal Register 59(235):63283–63285.

Federal Register. 1995. Compensation for certain undiagnosed illnesses. Final rule. Federal Register 60(23):6660–6666.

Federal Register. 2001a. Disease associated with exposure to certain herbicide agents: Type 2 diabetes. Final rule. Federal Register 66(89):23166–23169.

Federal Register. 2001b. Extension of the presumptive period for compensation for Gulf War veterans’ undiagnosed illnesses. Interim final rule with request for comments. Federal Register 66(218):56614–56615.

Federal Register. 2021. Rule: Department of Veterans Affairs—presumptive service connection for respiratory conditions due to exposure to particulate matter. Federal Register 86(148):42724–42733.

Federal Register. 2022. Rule: Department of Veterans Affairs—presumptive service connection for rare respiratory cancers due to exposure to fine particulate matter. Federal Register 87(80):24421–24429.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2008. Improving the presumptive disability decision-making process for veterans. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2011a. Blue Water Navy Vietnam veterans and Agent Orange exposure. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2011b. Long-term health consequences of exposure to burn pits in Iraq and Afghanistan. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2020a. Respiratory health effects of airborne hazards exposures in the Southwest Asia theater of military operations. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NASEM. 2020b. Assessment of long-term health effects of antimalarial drugs when used for prophylaxis. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NRC (National Research Council). 2009. Contaminated water supplies at Camp Lejeune: Assessing potential health effects. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

President’s Commission on Veterans’ Pensions. 1956. Veterans’ Benefis in the United States. A Report to the President. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/Bradley_Report.pdf (accessed June 21, 2023).

U.S. House of Representatives. 2007. Findings of the Veterans’ Disability Benefits Commission. October 10, 2007. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-110hhrg39461/html/CHRG-110hhrg39461.htm (accessed April 13, 2023).

VA (Department of Veterans Affairs). 2015a. Health Topics A to Z Index. https://www.va.gov/health/topics/index.asp (accessed June 20, 2023).

VA. 2015b. Federal Benefits for Veterans, Dependents and Survivors: Chapter 2 Service-connected Disabilities. https://www.va.gov/opa/publications/benefits_book/benefits_chap02.asp (accessed March 23, 2023).

VA. 2019. Compensation Benefit Rates. https://www.benefits.va.gov/compensation/rates-index.asp (accessed March 23, 2023).

VA. 2020. Benefits Overview for Military Exposures. https://www.publichealth.va.gov/exposures/benefits/index.asp (accessed June 9, 2023).

VA. 2021. Service-Connected Disabled Veterans by Disability Rating Group: FY 1986 to FY 2019. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/Utilization.asp (accessed March 31, 2023).

VA. 2022. Veterans Benefits Administration Annual Benefit Report: Fiscal Year 2022. https://www.benefits.va.gov/REPORTS/abr/docs/2022-introduction-appendix.pdf (accessed July 7, 2023).

VA. 2023a. Eligibility for VA Disability Benefits. https://www.va.gov/disability/eligibility/ (accessed March 31, 2023).

VA. 2023b. VA Disability Compensation. https://www.va.gov/disability/ (accessed March 13, 2023).

VA. 2023c. Veterans Health Administration: Providing Health for Veterans. https://www.va.gov/health/ (accessed March 24, 2023).

Veterans Administration. 1921. Internal memorandum implementing Veteran’s Bureau Regulation No. 11. Washington, DC: VA.

ANNEX

Improving VA’s Presumption Decision Process (PDP)

- PURPOSE: This document describes the new process the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) will use to evaluate whether a specific medical condition is or is not associated with an environmental exposure. If an association is found, this document further describes how the condition could reach presumptive status.

-

BACKGROUND: VA is responsible for the administration of health care and benefits programs for eligible Veterans, caregivers and their survivors. In evaluating the association between an environmental exposure and a specific medical condition, multiple challenges exist. First, while the gold standard in medical research is the Randomized Clinical Trial (RCT), there are no such studies when it comes to military environmental exposures. Moreover, it would be unethical to conduct this type of study. The use of RCT methodology, therefore, cannot be applied to the evaluation of environmental exposures. Other methods are needed. In addition, it can take years postexposure for many of these medical conditions to present themselves (in the case of certain cancers, for example), making the determination of an association with an exposure even more difficult. The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) in their 2008 report noted:

For some medical conditions that develop after military service, the scientific information needed to connect the health conditions to the circumstances of service may be incomplete. When information is incomplete, Congress or [VA] may need to make a “presumption” of service connection so that a group of Veterans can be appropriately compensated. The missing information may be about the specific exposures of the Veterans, or there may be incomplete scientific evidence as to whether an exposure during service causes the health condition of concern.4

The presumptive process VA historically used was often a decades-long process. It required waiting for Veterans to develop medical conditions, having providers or scientists observe and report potential patterns, and publishing these findings in peer-reviewed

___________________

4 National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine (NASEM) (previously the Institute of Medicine) report, “Improving the Presumptive Disability Decision-Making Process for Veterans,” published in 2008.

-

journals. VA would also conduct its own public health surveillance studies and conduct scientific literature reviews to evaluate whether certain conditions occurred more frequently among specific cohorts of Veterans who may have been exposed to the same environmental agent. This, too, often took years. A valuable instrument in this regard were the NASEM reports, some of which were mandated by Congress (such as through the Agent Orange Act of 1991, Public Law 102-4, 105 Stat. 11 (codified in part at 38 U.S.C. § 1116), and the Omnibus Consolidated and Emergency Supplemental Appropriations Act of 1999, Public Law 105-277, 112 Stat. 2681, Title XVI—Service Connection for Persian Gulf War Illnesses (codified in part at 38 U.S.C. § 1118). NASEM consensus reports, however, require an average of two years to complete, and during this time, the conditions of concern may change and increases in incidence/prevalence or new information may become available, such that in some cases, by the time the NASEM reports are published, they are already out of date. This process is frustrating for Veterans, their families and caregivers, as well as their clinical teams, and has led to delays in Veterans receiving the health care and benefits they have earned and deserve.

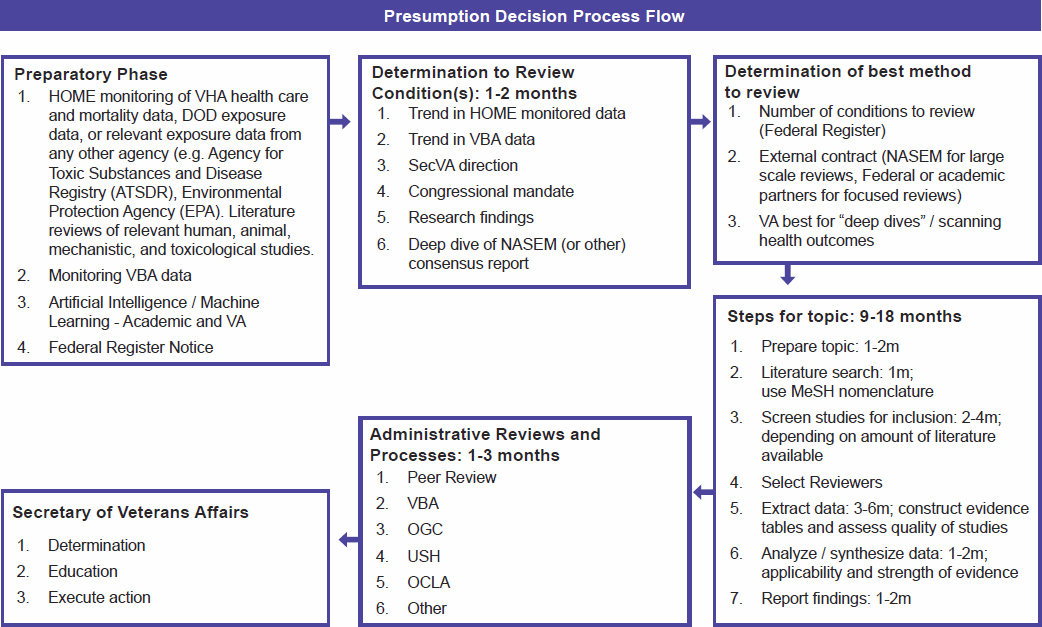

When the most recent NASEM report found evidence of an association between particulate matter and three respiratory symptoms, the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) examined recent surveillance data from VHA health care records and then partnered with the Veterans Benefits Administration (VBA) to obtain claims data. VA conducted additional scientific reviews of recently published studies not available to NASEM, (including relevant articles in non-Veteran populations). This led to three newly added presumptive conditions in fiscal year (FY) 2021: asthma, rhinitis and sinusitis. This experience led VA to recognize that it could improve its presumptive decision-making process to be more proactive and transparent. The Secretary of Veterans Affairs directed VA to update the Presumption Decision Process (PDP) to assess the available scientific data in as timely a fashion as possible, consider the addition of other relevant information, including VBA claims data, and enhance the transparency of the process.

- SELECTION OF CONDITIONS: VA will use several factors to develop a list of medical conditions to be considered for presumptive status. These factors include, but are not limited to, the number of Veterans potentially affected, severity of the condition, amount of literature available, and VHA and/or VBA trends. VA will solicit

- input for conditions to be reviewed from external stakeholders, including Veterans and their families and caregivers, Veterans Service Organizations, Congress, and the public at large. This is in keeping with recommendations in the NASEM report on improving the presumptive decision-making process.

- Federal Register Notification: At least once each year, VA will publish in the Federal Register a list of conditions the Department plans to evaluate, explain why the conditions were chosen for evaluation, and solicit input from the public. This approach allows for public participation and enables transparency. VA will use the feedback to finalize the list of conditions for evaluation.

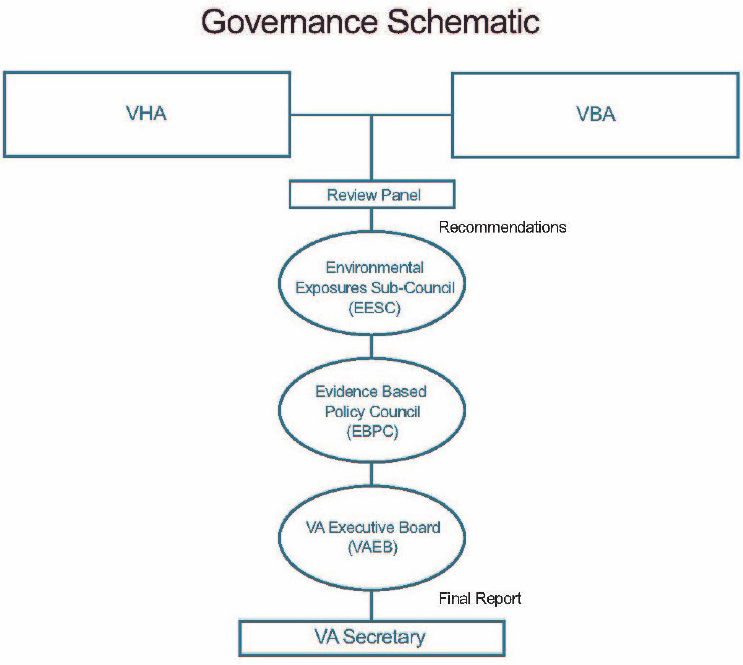

- Data gathering: VHA and VBA data for the conditions of interest, including those that come from the Federal Register feedback, will be compiled and submitted to the Environmental Exposures Sub-Council (EESC). The EESC will review and propose a prioritization scheme for the order in which the conditions are recommended to be reviewed and prepare the rationale for the Evidence-Based Policy Council (EBPC).

- Evidence Base Policy Council (EBPC): The EBPC will endorse or reprioritize the EESC list and forward to the VA Operations Board and/or the VA Executive Board for Secretary of Veterans Affairs approval to determine the final list and prioritization.

-

COMPOSITION OF REVIEW PANEL: Once the list is approved by the VA Secretary, the EESC co-chairs will convene a review panel. There will be one panel convened per medical condition or set of related medical conditions, and the composition and size of the panel will be based on the amount of scientific evidence and data available for review.

At a minimum, each panel will include:

- Four members from VHA (Health Outcomes Military Exposures/HOME and/or the Office of Research and Development)

- Two members from VBA

- One member from a Federal Agency with subject-matter-experts with a substantive understanding of the exposure(s)

- One member from the DoD Deployment Health Working Group

- VA or other Federal agency medical specialty members as needed for the specific condition(s) for review

- EQUIPOISE: When the evidence of an association between an environmental exposure and a medical condition is uncertain, and

-

a case for an association can be made just as easily as a case against an association, a state of equipoise exists. Use of the concept of equipoise was suggested by the 2008 NASEM report as one of the ways to improve VA’s presumptive decision-making process and has been adapted by the PDP. Drawing from the suggestions in that report, a presumptive status recommendation would be based on the strength of the evidence for or against an association (NASEM used causation, but VA’s standard is association). Those standards are defined as:

- Sufficient: the evidence is sufficient to conclude that an association exists.

- Equipoise and Above: the evidence is sufficient to conclude that an association is at least as likely as not, but not sufficient to conclude that an association exists.

- Below Equipoise: the evidence is not sufficient to conclude that an association is at least as likely or not or is not sufficient to make a scientifically informed judgment.

- Against: the evidence suggests the lack of an association.

In the event that the strength of the evidence is at equipoise, (that is, when the weight of the evidence is equally balanced as to whether an association exists), VA will make the determination after review of VBA claims data and other factors.

-

COMPONENTS AND METHODS THAT ARE PART OF THE REVIEW PROCESS:

- Health Care Data: The PDP will review VHA data in the form of epidemiological research studies and ongoing health care and population surveillance.

- Scientific Literature: Relevant medical and scientific literature will be pulled using recognized Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) keywords. This data pull will include military and civilian human, animal, toxicologic and mechanistic studies. Research will be evaluated for the strength of the science based on study design, size, sources, reproducibility, or number of papers with similar findings, existence of conflicting studies, whether the study was peer-reviewed, whether there are limitations or flaws noted in the study, and whether there are any criticisms of a study and for what issues. In the future, and when possible, the use of machine learning algorithms and text-mining tools for continuous review of scientific literature will be used.

-

- VBA Claims Data: The PDP will include review of VBA claims data for trends, such as claim rate, rate grant, and service connection prevalence, analysis of differences in deployed and nondeployed or other cohort characteristics and may be used to assist in development of presumption when the science is at equipoise. VBA claims data may also be used to inform which reviews of conditions are indicated.

- Other Factors: Additional factors will be reviewed, and include, but are not limited to, deployments to combat zones, morbidity, mortality and prognosis associated with the medical condition, rarity of the condition, quantity/quality of available science and data, and feasibility of producing future, methodologically sound scientific studies.

- Rare Conditions: In some cases, the incidence of a disease, particularly certain types of cancer, is considered to be rare. VA defines rare cancers as those with an annual U.S. incidence rate of fewer than 6 cases per 100,000 individuals in the general US population. This standard was adopted by the American Cancer Society, and is used by the National Institutes of Health. The same standard has also been adopted internationally. The consortium from the European Union, Surveillance of Rare Cancer in Europe (RARECARE), defines rare cancers as those with fewer than 6 cases per 100,000 people per year. When scientific evidence is available, it will be used in the evaluation of these conditions. In some cases, it is unlikely that there will ever be sufficiently well-designed epidemiologic studies of different cohorts for VA to evaluate and make a determination using the general standards of the presumptive model alone. In these cases, there need to be additional standards or an alternate process to evaluate the available evidence regarding such rare conditions. Beyond rarity of the condition, VA developed guiding principles that will be incorporated as part of the evaluation process and include, but not be limited to, the catastrophic nature of the disease and biological plausibility. VA also adapted and will utilize the nine principles of the Bradford Hill Criteria to further evaluate these rare conditions (Appendix A). The Bradford Hill Criteria have been used widely in public health research to evaluate the strength of an association between a presumed exposure and an observed effect. VA will also examine VHA health outcomes clinical data and VBA claims data for trends that may signal an association between the target condition and

-

- environmental exposure of interest. Cancer, in particular, may have its onset long after military service, is often a challenging illness, and prognosis may depend on quick identification and treatment at early stages to achieve the best outcomes. These guiding principles ensure that benefits are not denied simply due to the rarity of a condition.

-

STANDARDIZED EVALUATION OF THE SCIENCE:

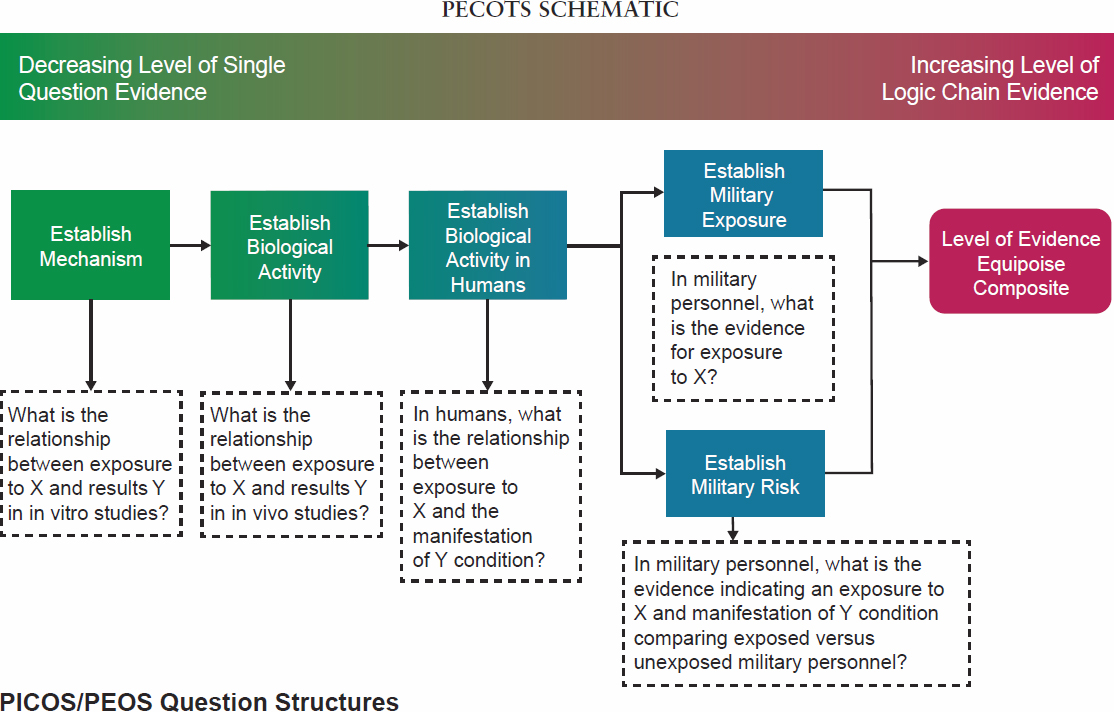

- PECOTS FRAMEWORK: The scientific review panels will employ a consensus-based evaluation process that incorporates and adapts the PICOTS (Patient, Intervention, Comparator, Outcomes, Timing, Setting) Framework to define the strength of the evidence base. Though originally designed for clinical trials, the PICOTS framework is commonly modified in exposure science literature to PECOTS whereby ‘E’ refers to exposure of interest (SEE PECOTS SCHEMATIC). Though full consensus regarding presumptive status is the objective, an 80% majority with notation of disagreement is the benchmark for presumptive status recommendations that will be sent to the Secretary for final decision-making. Dissenting views will be included in the recommendations.

-

-

Extraction of key data elements from evidence sources to facilitate evaluation:

Relevant information from each source of evidence (e.g., published literature, claims data) will be abstracted using a standardized review process which will facilitate expediting the evaluation. This can be performed in parallel with the PECOTS framework to streamline review. For example, a template can be provided for data extractors to identify key data elements (e.g., number of patients, type of exposure, exposure duration, etc.) to facilitate evaluation by subject matter experts (SME). Future efforts may consider artificial intelligence strategies to further expedite this process and perform quality assurance activities.

- Determination of levels of evidence: A semi-quantitative approach to evaluate the quality of evidence will be employed based on the “Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE)” structure.5. The GRADE structure allows SMEs to assign certainty ratings to the strength of evidence. Importantly, it considers factors that diminish (e.g., bias, imprecision) and enhance (e.g., large effect, dose-response) the overall quality of evidence.

-

Extraction of key data elements from evidence sources to facilitate evaluation:

___________________

5 Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, Oxman AE. Handbook for grading the quality of evidence and the strength of recommendations using the GRADE approach. Updated October 2013.

-

GOVERNANCE PROCESS FOR FINAL PRESUMPTIVE DECISIONS

Once the review panel completes its work, it will draft a report summarizing its findings and conclusions as to the strength of the evidence and whether an association exists between a medical condition and an environmental exposure. If the panel concludes an association exists or does not exist, the panel will submit its recommendations, for or against, in the form of a written report to the Environmental Exposures Sub-Council (EESC). Once concerns and questions are addressed and the EESC concurs, the report will be presented to the Evidence-Based Policy Council for additional concurrence, and then to VA Executive Board for approval of the recommendation. The report is then submitted to the Secretary for final approval (Governance Schematic).

APPENDIX A

The Bradford Hill Criteria are especially helpful in the evaluation of an association between an environmental exposure and a medical condition and have been used extensively in the public health literature. The criteria are:

- Strength (effect size): A small association does not mean that there is not a causal effect, though the larger the association, the more likely that it is causal.

- Consistency (reproducibility): Consistent findings observed by different persons in different places with different samples strengthens the likelihood of an effect.

- Specificity: Causation is likely if there is a very specific population at a specific site and disease with no other likely explanation. The more specific an association between a factor and an effect is, the bigger the probability of a causal relationship.

- Temporality: The effect has to occur after the cause (and if there is an expected delay between the cause and expected effect, then the effect must occur after that delay).

- Biological gradient (dose-response): Greater exposure generally leads to greater incidence. However, in some cases, the mere presence of the factor can trigger the effect. In other cases, an inverse proportion is observed: greater exposure leads to lower incidence.

- Plausibility: A plausible mechanism between cause and effect is helpful (but Hill noted that knowledge of the mechanism is limited by current knowledge).

- Coherence: Coherence between epidemiological and laboratory findings increases the likelihood of an effect. However, Hill noted that “... lack of such [laboratory] evidence cannot nullify the epidemiological effect on associations”.

- Experiment: “Occasionally it is possible to appeal to experimental evidence”.

- Analogy: The use of analogies or similarities between the observed association and any other associations.

Points of Contact for this report:

Ms. Laurine Carson

Deputy Executive Director, Policy and Procedures, Compensation Service VBACO

Dr. Patricia Hastings

Chief Consultant, HOME

This page intentionally left blank.