Review of the Department of Veterans Affairs Presumption Decision Process (2023)

Chapter: Summary

Summary

The United States has a long history of recognizing and honoring the service and sacrifices of its veterans. Exposures experienced during military service may result in or exacerbate a physical or mental injury or illness (condition). These service-connected disabilities are adjudicated based on a diagnosed medical condition and may occur during service or develop after a veteran leaves the military. U.S. veterans who have incurred a disability due to their military service may be eligible for benefits from the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), including health care and service-connected disability compensation.

Undoubtedly, many veterans and service members (who will one day be veterans) have encountered exposures related to their military service that are or may be positively associated with developing or exacerbating physical or mental health conditions. For some conditions, the scientific information needed to connect a veteran’s service or a particular military exposure with them may be impossible to obtain, not exist, or be incomplete; when this occurs, Congress or VA may make a “presumption” of service connection. Since 1921, Congress and VA have granted numerous presumptions for service-connected disabilities, with an aggregate cost of trillions of dollars. If a veteran is a member of a specific exposed group, defined by dates and locations of service, and has a diagnosed service-connected disability, then they may be entitled to receive health care and compensation without having to prove that their disability was the result of military service; that is, the veteran no longer has the burden of proving the connection. In fiscal year 2022 alone, VA disbursed an estimated $120.7 billion in compensation for service-connected disabilities to 5.9 million veterans.

STUDY ORIGIN AND APPROACH

The Sergeant First Class Heath Robinson Honoring Our Promise to Address Comprehensive Toxics Act (PACT Act) of 2022 (PL 117-168) and the VA initiatives that led to the revision of VA’s presumption decision process were based on a sincere and well-justified desire to create a process that is scientifically based, fair, consistent, transparent, timely, and veteran centric. Section 202 §1176 of the PACT Act called for the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (the National Academies) to review the VA process and was the basis for the committee’s Statement of Task (see Box S-1). The committee was asked to review the eight-page pre-decisional VA presumption decision process document (dated June 14, 2022, and replicated in its entirety as an annex to Chapter 1). This document describes VA’s process to identify medical conditions to evaluate for an association with an environmental exposure encountered during military service for presumption status, the factors that such an evaluation entails, and the governance process for the review and approval of a presumption recommendation.

The committee was not asked to design or redesign a new framework for the presumption decision process, nor was it asked to apply the proposed process to a condition as a case study or vignette. The committee’s assessment of the VA presumption decision process is not intended to set or

change the statutory standards VA is required to use for the process or any specific presumption decision. Furthermore, although the 2008 National Academies report that served as the basis for several components of the revised VA presumption decision process was considered, the committee was not asked to assess to what extent VA accepted or implemented the recommendations in that report, nor was it bound to agree with, support, or endorse any aspect of it. Finally, the use of the presumption decision process to make a presumption of exposure (not specifying a medical condition) was outside the committee’s charge.

The National Academies committee comprised 10 members with expertise in decision science and causal decision making, systematic review methodologies, causal inference, environmental epidemiology, chronic disease epidemiology, mental health disorders, statistics, exposure assessment, health risk assessment, toxicology, bioethics, military and veterans’ health, and VA administrative processes. Given the congressional mandate and the short time frame the committee had to produce its report, it held only three full meetings and several subgroup meetings between March and June 2023 to consider evidence and write its report.

The committee’s several information-gathering activities included invited presentations, information requests to VA, requests for public comment, and peer-reviewed scientific literature. The first meeting included presentations from VA representatives and congressional staff of the Senate and House Committees on Veterans’ Affairs to elucidate the committee’s charge and describe relevant aspects of the VA presumption decision process. VA and congressional staff both indicated that they wanted the process to be fair, consistent, transparent, timely, and veteran centric. Although VA told the committee that the revised process is being implemented and provided background and supplemental documentation to the committee, it did not include any information on the actual use of the process.

The presumption decision process is not specific to any one era or cohort of veterans and must be applicable to a broad range of environmental exposures and health conditions, including mental health conditions. However, the committee notes that the document contains no specific mention of mental health conditions. The committee was cognizant that VA’s presumption decision process and its corresponding document could not be too prescriptive but must provide enough detail to encompass a range of medical conditions, environmental exposures, and conflict eras. The process must also be feasible, flexible, and have the appropriate elements to fulfill its purpose (determining recommendations and the associated approval process regarding conditions qualifying for a presumption), and it requires a balance between brevity and the detail necessary to understand and implement it.

GOVERNANCE OF THE PRESUMPTION DECISION PROCESS

The presumption decision process has two major aspects: a governance process and an evaluation of scientific evidence for a particular condition. The former, as described in the presumption decision process document, has several elements that are difficult to understand, including the organizational structure, timing of each review, and role of each panel, council, or board.

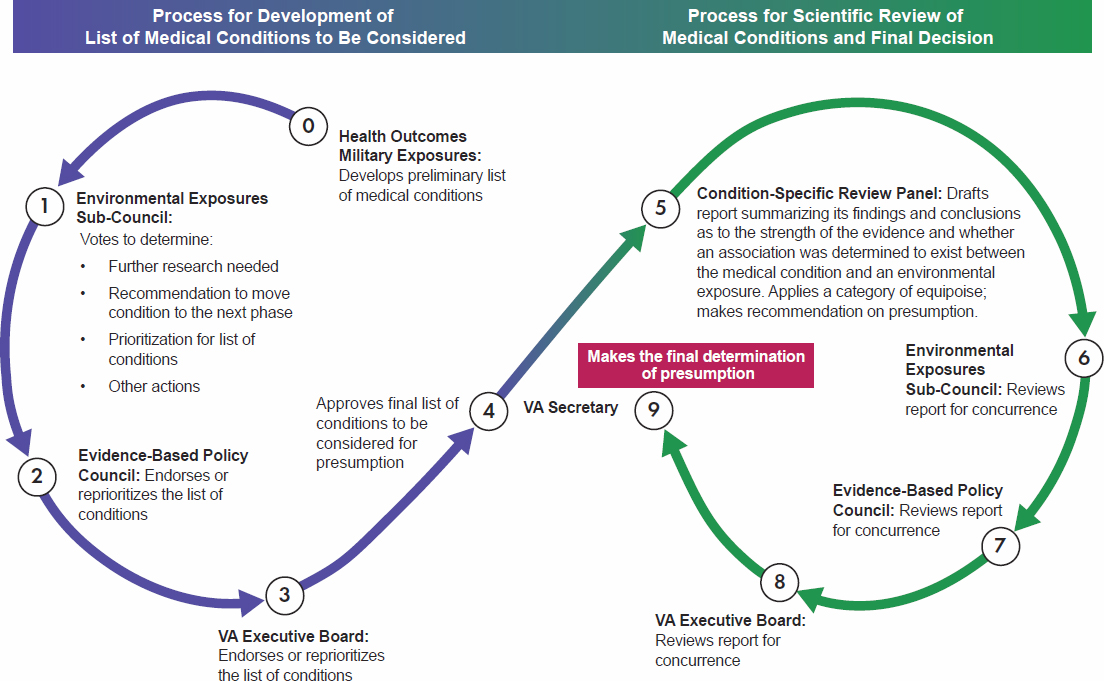

The governance process is described in sections 3, 4, and 8 of the presumption decision process document. Figure S-1 shows the committee’s understanding of the entities that have a role, which can be divided into two groups: the panels and councils that directly perform or are involved in the scientific reviews leading to a decision on which conditions to consider for evaluation and recommend for presumption, and the councils and boards that are focused on the policy, political, and financial aspects. VA’s Office of Enterprise Integration, which reports to the VA Secretary, provides the overarching governance for the entire process.

The VA decision-making process consists of nine steps that are divided into two phases. In the first phase, shown in blue, a list of conditions to be considered for evaluation for presumptive status is developed and prioritized. In the second phase, shown in green, a condition-specific scientific review is conducted and a recommendation for presumption is made.

Step 0 in the first phase, led by VA’s Health Outcomes Military Exposures office, begins with condition identification, prioritization, and selection and includes monitoring of Veterans Health Administration (VHA) and Veterans Benefits Administration (VBA) data, literature reviews, consideration of congressional and public input, and some evidence synthesis. The review and approval process for the list of conditions involves four VA entities: the Environmental Exposures Sub-Council (step 1), the Evidence-Based Policy Council (step 2), the VA Executive Board (step 3), and the VA Secretary (step 4).

Once the VA Secretary approves the final list of conditions to be evaluated, the second phase begins. That process starts with the condition-specific review panel (step 5), which screens, assesses, synthesizes, and integrates the evidence and issues a report on the likelihood of a positive association between an environmental exposure and a specific condition with a corresponding presumption recommendation. This report is reviewed by the same councils and boards (steps 6–8) from the first phase, and they either endorse or reject the condition-specific review panel’s recommendation. The VA Secretary makes the final determination of whether to approve a recommendation. VA states that the presumption decision process itself starts when the scientific evaluation of evidence is complete and a report with a presumption recommendation is submitted to the governance process.

The committee finds that, in general, the governance process used to approve the list of conditions and a condition-specific report and presumption recommendation is reasonable and logical.

However, the overarching governance (Figure S-1, steps 0–8) is not clearly described, with no information on the criteria or other considerations used by the boards and councils to review and approve the list of conditions or the condition-specific reports. There is also very little information on the expertise that will be included on the various panels, councils, and boards, and this is particularly important for the review panels, where the scientific expertise required will vary substantially depending on the condition selected for review (rather than the amount of evidence to be reviewed). In addition to the lack of information on membership of the condition-specific review panel, not specifying the standardized criteria to be used could result in inconsistencies among panels with regard to depth of review, adequacy of needed panel expertise, application of evidence evaluation standards, or decision process for a presumption recommendation. The committee appreciates that not all internal processes can or should be made public; however, making such criteria public to the extent practical will enhance fairness, consistency, and transparency.

The committee concludes that the composition of any review panel needs to ensure that there is sufficient subject matter expertise including core methodologic expertise in the systematic review of environmental health, and that there is a mechanism to obtain the perspective of the affected community. Additionally, the panel would have sufficient capacity to review the totality of the evidence in a timely manner.

The committee concludes that the presumption decision process document provides insufficient detail on the governance process for both the review and approval of the list of conditions to be considered for presumption and the review of a condition-specific presumption report. Although not all decision-making attributes can be made public, the committee further concludes that a high-level distillation of the process, entities, and criteria for both positive or negative decisions could be made publicly available.

Recommendation 3-1: The committee recommends that VA make explicit the operational criteria or guiding principles for each of the governance steps and provide a description of the expertise and the entities represented at each step. To the extent possible, these criteria or principles and descriptions should be made publicly available either in the presumption decision process document or by reference to other documentation.

Given that the process will likely evolve as it is used, VA will need a process to pilot test any revisions and a responsible entity to oversee, evaluate, and make changes to it.

Recommendation 3-2: The committee recommends that once the presumption decision process has been used by several condition-specific review panels, it be reviewed periodically (by an entity internal or external to VA with the appropriate expertise) to assess whether scientifically based, fair, consistent, transparent, timely, and veteran-centric decisions have been made and whether any modifications to improve the process are necessary.

SCIENTIFIC ASPECTS OF THE PRESUMPTION DECISION PROCESS

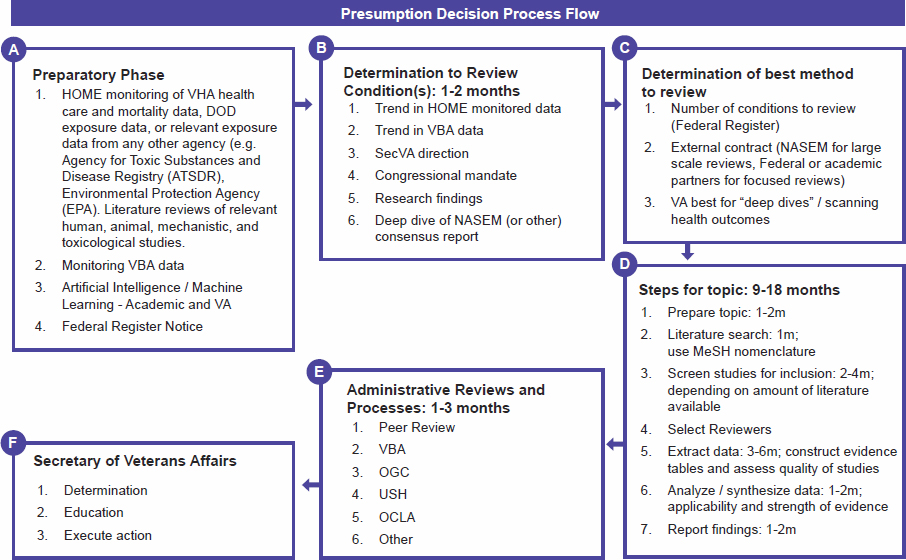

The scientific aspects of the presumption decision process are presented in VA’s pre-decisional document in sections 3, 5, 6, and 7. The scientific steps that VA uses for evidence review (see Figure S-2) can be summarized as (1) the planning and preparatory phase, (2) a standardized scientific assessment, and (3) making a conclusion regarding the likelihood of a positive association. In the VA presumption decision process document, these steps address the types of evidence to be reviewed (section 6); use of a PECOTS (population, exposure, comparator, outcomes, timing, and setting) framework “to define the strength of the evidence” and GRADE (grading of recommendations assessment, development and evaluation) to “evaluate the quality of evidence” (section 7); and determination of the likelihood of a positive association (section 5).

The committee finds an inconsistent correspondence between the four sections (sections 3, 5, 6, and 7) in the presumption decision process document that pertain to scientific aspects of the process and in the steps of the flow diagram (Figure S-2) included in that document.

The committee concludes that the accompanying section order and content narrative in the VA presumption decision process document do not provide sufficient detail to understand the activities in each box of the flow diagram or the items within a box—specifically, how the steps are defined or operationalized.

The National Toxicology Program (NTP), Environmental Protection Agency, World Health Organization, and other federal and international organizations use methods, such as systematic reviews, to assess potential environmental hazards; this process may be broadly applicable to the VA presumption decision process. The methods described by NTP and similar

NOTE: DOD = Department of Defense; HOME = Health Outcomes Military Exposures; MeSH = Medical Subject Headings; NASEM = National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; OCLA = Office of Congressional and Legislative Affairs; OGC = VA Office of General Counsel; SecVA = Secretary of VA; USH = Undersecretary for Health (VA); VA = Department of Veterans Affairs; VBA = Veterans Benefits Administration; VHA = Veterans Health Administration.

SOURCE: VA presumption decision process document (2022); boxes have been labeled (A–F) by the committee for clarity.

organizations are considered by the committee to be the scientific best practices for the use of systematic reviews. The methods begin with problem formulation (assessment planning) and continue through protocol development, evidence identification and selection, individual study assessment (including critical appraisal), body of evidence assessment (including synthesis and evaluation of the confidence or strength of evidence), and reporting of the results. Although an example of NTP’s systematic review process is given in Chapter 4 because it may be broadly applicable, other systematic review processes may be used or adapted. However, the presumption decision process document presents these topics differently from the more recognized general scientific steps given by these scientific best practices.

In the presumption decision process document, a planning phase occurs for two separate functions: identifying, prioritizing, and selecting conditions to include on the list of medical conditions to be considered, and conducting the review process for a specific condition. In the latter, the planning phase typically will begin after condition selection and informs determination of the mechanism (e.g., a systematic review) to be used to conduct the review.

The committee finds that there are insufficient details in the presumption decision process document to determine if the preparatory phase for both the development of the list of conditions to be considered for presumption status and the development of a condition-specific report is consistent with scientific best practices for identifying, selecting, and reviewing data from each source. The presumption decision process document also lacks details on the components, criteria, and methods related to the selection of review type.

The committee concludes that insufficient details are provided on condition identification, prioritization, and selection, either for the list of medical conditions to be considered for presumption or for condition-specific evaluation, in the presumption decision process document to assess how these steps would be conducted.

The PECOTS framework is used to guide the development of a protocol that specifies the scope and structured research questions in detail and outlines the methodology for the evidence review. VA states that PECOTS is a consensus-based evaluation process, which is a misuse of PECOTS.

The committee finds that, given the variety of conditions to be evaluated and the differences in the amount, type, and quality of the evidence to be reviewed for any condition, the scientific evaluation process will need to be flexible to address the research question that is formulated using PECOTS.

The committee concludes that the PECOTS terminology, the PECOTS schematic (including its content, order, and organization), and the accompanying text of the presumption decision process document are not consistent with scientific best practices.

Section 6 of the presumption decision process document lists five data types or components that provide information for conditions being considered: VHA health care data, scientific literature, VBA claims data, other factors, and rare conditions.

The committee finds that leveraging a variety of data and evidence sources to inform topic selection is appropriate; however, VA provides only cursory explanations for the types of data that may be reviewed and no information on the criteria that will be applied to them in terms of data quality, validity, or reliability or on how they will be obtained and screened for inclusion or exclusion.

Section 7 of the VA presumption decision process document, which outlines the standardized evaluation process to be used, does not explain if or how individual studies will be appraised for validity and reliability. Section 7C indicates that VA uses a “semi-quantitative approach” to evaluate the quality of evidence and determine the levels of evidence based on the GRADE structure. VA does not explain what it means by a “semi-quantitative approach” and how this approach relates to VA’s proposed use of PECOTS and GRADE for evidence assessment. GRADE is a tool to grade the quality or certainty of evidence and make a determination about the strength of recommendations.

The threshold for a presumption is defined in the presumption decision process document as the likelihood or probability that a positive association “is at least as likely as not” (termed “equipoise”). The document lists four standards with their associated definitions but lacks information on how a “standard” of equipoise is to be operationalized and applied to produce a presumption recommendation, which is a notable shortcoming.

The committee concludes that the term “equipoise” denotes a lack of consensus across the medical community and that the term as required by law to be used in the presumption decision process is inconsistent with the current scientific use of it.

The committee was unable to judge whether the pre-decisional presumption decision process document and the activities in individual steps in the process align with current scientific standards, as asked in the Statement of Task. Moreover, it was not able to comment on the fairness or

consistency of the process primarily due to the organization of the document, the lack of detail on how the process will be operationalized, and the lack of specifics for each step, such as the lack of criteria on how the evidence will be extracted, reviewed, and synthesized and how evidence will be appraised for validity and reliability. The lack of detail in the presumption decision process document and supplemental documentation VA provided to the committee makes it difficult for the committee to judge the scientific appropriateness of the process.

The committee finds that VA does not define the decision-making criteria for using the evidence synthesis to determine the strength of association between an exposure and a medical condition, particularly given the potential use of disparate evidence streams. The evidence-to-decision process also is not defined.

The committee concludes that the overall usefulness of the presumption decision process document could be improved by enhancing the existing description of the evaluation process, including detail on how each step will be operationalized, providing a logical one-to-one correspondence between the text and the flow diagram, and incorporating scientific best practices, by either including additional details in the VA presumption decision process document or referencing other documentation.

Recommendation 4-1: The committee recommends that VA’s presumption decision process contain sufficient detail to define how it will operationalize each step of the scientific process, either in the presumption decision process document or by reference to other documentation, beginning with condition identification and selection, through evidence review, to the application of a standard on the likelihood of a positive association.

Recommendation 4-2: The committee recommends that VA model its scientific evaluation of the environmental health evidence using existing standardized and structured approaches. Such a standardized evaluation process should include a formal problem assessment and study planning phase; development of a protocol that addresses the structured research question (e.g., PECOTS) and includes a detailed literature search strategy and inclusion/exclusion criteria; and a report that presents the systematic identification and selection of evidence, critical appraisal of the validity and reliability of studies, synthesis and integration of a body of evidence, and a structured approach to determining conclusions (levels of evidence) about the scientific evidence.

Recommendation 4-3: The committee recommends that VA use existing frameworks, tools, and approaches designed for environmental health assessments (e.g., NTP; World Health Organization Framework on the use of systematic review in chemical risk assessment) and apply or adapt them in a manner that aligns with scientific best practices.

SYNTHESIS OF THE PRESUMPTION DECISION PROCESS ASSESSMENT

This section discusses several overarching topics the committee identified in its assessment of both the governance and the scientific aspects of the process as presented in the pre-decisional presumption decision process document. These include areas with significant problems, including the lack of description so that the committee was unable to judge if scientific best practices are used; weak logical flow; and lack of details, criteria, or standards. The presumption decision process is not specific to any one era or cohort of veterans and must be able to accommodate a broad range of environmental exposures and health conditions, including mental health conditions. Therefore, the committee was cognizant that VA’s presumption decision process and its corresponding document could not be too prescriptive but must provide enough detail to encompass a range of medical conditions, environmental exposures, and conflict eras.

Use of Scientific Best Practices

As defined, the committee considers the methods described by NTP and other agencies noted to be the scientific best practices for use of systematic reviews to address environmental health research questions. Use of scientific best practices does not mean applying rigid rules or absolute standards; rather, it allows for the elements or steps to encompass a mechanism or guidance to promote, ensure, and document an unbiased and scientifically justifiable decision process. Similarly, the criteria guiding the evaluation and decision-making process for governance are intended to guide the questions that the reviewing panels, councils, and boards should ask while being flexible to accommodate the available data and analyses.

Chapters 3 and 4 present many similar observations and findings related to the need for additional clarity regarding descriptions or outputs of the evaluation standards and guidance or steps in the process, and, as a result, note numerous potential interpretation challenges. The presumption decision process document oscillates between providing high-level features of the process and very specific information, and not all the information is entirely correct (e.g., description of PECOTS) or relevant (e.g., some of the description of rare conditions).

On the whole, the committee finds that many of the elements necessary for the presumption decision process to be scientifically based, fair, consistent, transparent, timely, and veteran centric are identified in the document. However, the elements are not presented in the order in which they would be conducted, and detail is insufficient on how they would be operationalized for the committee to determine whether they are in accordance with scientific best practices.

The committee concludes that although the components and methods important to conducting assessments in accordance with scientific best practices noted in sections 3, 5, 6, and 7 of the presumption decision process document are necessary, viable, and worthwhile, their descriptions are inadequate and need to be articulated in the document itself or provided in other supporting documentation. Furthermore, the components and methods need to be logically organized and described in a manner that is consistent with current scientific definitions and practices.

Logical Flow

The presumption decision process document lacks internal consistency. The governance and scientific aspects of the process are labeled as distinct sections but intertwined throughout the document and presented inconsistently and somewhat illogically, which also has implications for nonconformance with scientific best practices and may lead to misperceptions and misunderstandings. The sections of the process are presented in a way that does not follow a logical progression from developing the research question to determining a positive association. Moreover, the three sections (3, 4, and 8) that cover aspects of governance are not grouped together, and other sentences related to governance functions or decision making are embedded in the scientific sections. For example, section 7A includes a sentence regarding a benchmark of an 80% majority agreement on a presumption recommendation, although it is unclear at which governance step this agreement is reached.

Three figures were included in the presumption decision process document. The first was a “PECOTS Schematic” (embedded within section 7), the second was the “Presumption Decision Process Flow” (at the end of section 7), and the third was the “Governance Schematic” (at the end of section 8). The first two figures in particular are confusing and questionable, as they do not accurately represent the PECOTS concept or clarify the steps or decision points of the presumption decision process flow, respectively.

Details, Criteria, and Standards

The issue of lack of detail is a pervasive problem in the entire presumption decision process document, from the preparatory phase (identifying, prioritizing, and selecting conditions for evaluation) to the approval process for condition recommendation and for both the scientific and governance processes. The lack of detail in the document and supplemental documentation VA provided to the committee makes it difficult for the committee to judge the scientific appropriateness of the process and whether its elements are fair, consistent, and veteran centric. Although the presumption decision process document appropriately includes the major elements, information sources, and considerations for identification and scientific evaluation of conditions to be considered, it provides insufficient detail or specification of how the process will be implemented in practice, which affects transparency.

The committee finds that the presumption decision process is not inherently flawed; rather, the incomplete and opaque documentation of it makes it difficult to ascertain whether the process is fair, consistent, timely, and veteran centric.

The committee concludes that the presumption decision process document does not provide an overall framework for the process or sufficient detail for the steps within the framework to determine if the process can achieve its intended purpose, as the document does not clearly describe the use of scientific best practices or the criteria for many of the steps in the process.

The committee concludes that a final presumption decision process document that separates scientific and governance aspects to the extent possible, presents each step in sequential order, and provides a sufficient level of detail (for example, membership and criteria or standards used for decision making by each governance council or board, or how data sources will be used and weighted for scientific evaluation) would help to clarify decision factors and decision points along the process, leading to a more understandable, consistent, and cohesive process.

The committee acknowledges that VA desires a compact and not overly technical presumption decision process document; however, the details noted in these conclusions and recommendations need to be publicly available so that stakeholders can understand, if not agree with, the presumption decision process for a given condition and the information on which the decision was made. Many agency documents incorporate additional

details by citing existing documents, but if VA does incorporate these details by reference, it needs to be clear what information is being used from each referenced document.

FINAL OBSERVATIONS

To ensure that the presumption decision process serves its intended purpose, decisions made using it must be scientifically sound, with clear acknowledgment of the many challenges, assumptions, and uncertainties that are inherent in the scientific evidence base and the scientific review and governance processes that go into the decision regarding a condition-specific recommendation for or against presumption. To foster transparency and promote understanding by stakeholders (particularly veterans and their families who are potentially directly affected by those decisions), the public availability of the rationales and justifications for the decisions and the criteria and methods used to make them are vital. As science evolves and as methods for evidence-based decision making improve, periodic evaluation of scientific best practices is critical for maintaining an up-to-date presumption decision process. The pre-decisional presumption decision process document does not indicate whether or when any such updates might occur, but it is to be expected that after it has been applied to a variety of conditions, adjustments to the governance process and/or the scientific aspects of the evidence review process, including modifying the data sources or the review criteria, might be necessary.

Those responsible for drafting the presumption decision process document assembled many well-recognized and commonly used tools that support evidence synthesis and evidence-based decision making throughout the environmental health field. However, these tools were not presented with the completeness, detail, and clarity that the committee believes are necessary to understand and perform the assessments and make well-informed decisions. The committee believes that by reviewing and implementing the recommendations in this report, VA will meet its objective of creating a presumption decision process that supports scientifically based, fair, consistent, transparent, timely, and veteran-centric presumption decisions and that puts the needs of our nation’s veterans first.

This page intentionally left blank.