Improving Access to High-Quality Mental Health Care for Veterans: Proceedings of a Workshop (2023)

Chapter: 2 Experiences of Veterans Accessing Mental Health Services

Although the number of clinics and providers available within a system can be a useful measure of access, hearing from patients directly often paints a more complete picture of challenges and successes.

The rest of this chapter highlights perspectives from veterans and their families and caregivers, describing their experiences with accessing necessary mental health services, barriers they encountered, and potential ways forward to improve the scope of services.

IRAQ AND AFGHANISTAN VETERANS OF AMERICA (IAVA)

Advaith Thampi, legislative counsel and senior associate at IAVA, shared his experience with VA and IAVA’s policy work. When he left the U.S. Marine Corps in 2010, he perceived VA as a place for people with physical injuries or veterans of previous wars. But he eventually connected with VA through the Vet Center at his community college and, with friends’ support, visited the PTSD clinic at the VA medical center in Long Beach, California. He admitted he never would have taken himself there but said that VA has saved his life more than once. Having firsthand experience as a user of VA services, Thampi also emphasized the importance of VA’s work and how critical it was for so many patients that it quickly and efficiently shifted to telehealth during the pandemic. Thampi also noted that of the 22 service members each day that die by suicide, approximately 11 are not even connected to the VA network, illustrating that some of the challenges facing veterans and VA have to do with engagement and community access to services. Similarly, Thampi noted that some populations, such as rural veterans and underserved minorities, may not feel comfortable or welcome at VA facilities. IAVA partners with other veteran service organizations to try to reach people locally and also with organizations that are more familiar with homeless veterans or others who are not already connected to VA.

IAVA members complete an annual survey on VA services and how they can be improved; the results help inform IAVA’s legislative agenda. Thampi discussed some important and recent legislation affecting veteran mental health care. For example, since the Clay Hunt Suicide Prevention for American Veterans Act in 2015, there has been a fundamental paradigm shift in how people talk about mental health and counseling.1 The Commander John Scott Hannon Veterans Mental Health Care Improvement Act of 2019 (Hannon Act)2 has broadened mental health care and suicide prevention programs,

___________________

1 H.R. 203—114th Congress, 2015–2016.

2 For more on the Hannon Act, see https://www.congress.gov/116/plaws/publ171/PLAW-116publ171.pdf (accessed June 1, 2023).

expanding services such as the Staff Sergeant Fox grants, which provide services to local nonprofits. Another bill in development that Thampi has been advocating for is the VA Medicinal Cannabis Research Act through Senator Sullivan and Chairman Tester of the Senate Veterans Affairs Committee. Thampi noted that 88 percent of IAVA members support the research of cannabis for “unseen wounds.”

In addition to cannabis research and treatment, Thampi discussed the importance of peer support for veterans and other, more alternative, therapies, such as equine therapy, fishing therapy, yoga, mindfulness, and therapies using psychedelics. With the research data that continue to emerge from these therapies, the Hannon Act is an important support to understand their potential for therapeutic use among veterans (Green et al., 2021).

Last, Thampi touched on the 988 crisis line as a critical service. Separately, IAVA has a quick reaction force case management program that veterans or their family members can call 24/7, 365 days a year to talk to someone directly and receive assistance. This program can help veterans access VA benefits, assist with housing, or locate mental health resources. Veterans can also call just to talk to someone; they or their families do not have to be in crisis to use this service.

COHEN VETERANS NETWORK

Tracy A. Neal-Walden, chief clinical officer of the Cohen Veterans Network, noted that the United States has more than 2 million female veterans and that 17 percent of veterans will be women by 2040 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2020). Neal-Walden served for 24 years as a psychologist and said that despite the great benefits to being a female veteran, several concerns specific to women also demand more attention. She shared some of these concerns from her firsthand experience in clinical settings that are consistent with the literature. The first is military sexual trauma, which one in three women veterans have experienced (VA, n.d.); combined with combat exposure, this increases the incidence of PTSD and can impact readjustment to civilian life. She also noted that service members who enter military service in a noncombat role may be exposed to combat depending on where and when they deploy.

The second challenge is substance use disorder, which is higher among the female veteran population compared to their civilian counterparts (Teeters et al., 2017). Additionally, women veterans are more likely to die by suicide than women who don’t serve (VA, 2020). Part of this discrepancy is because veterans typically have greater access to firearms compared to civilians, Neal-Walden added. Another challenge is homelessness—many women with children in need of housing support may not seek it for fear of losing guardianship of their children. She emphasized the importance of assessing veterans for housing and food insecurity and unemployment during any screening or intake processes.

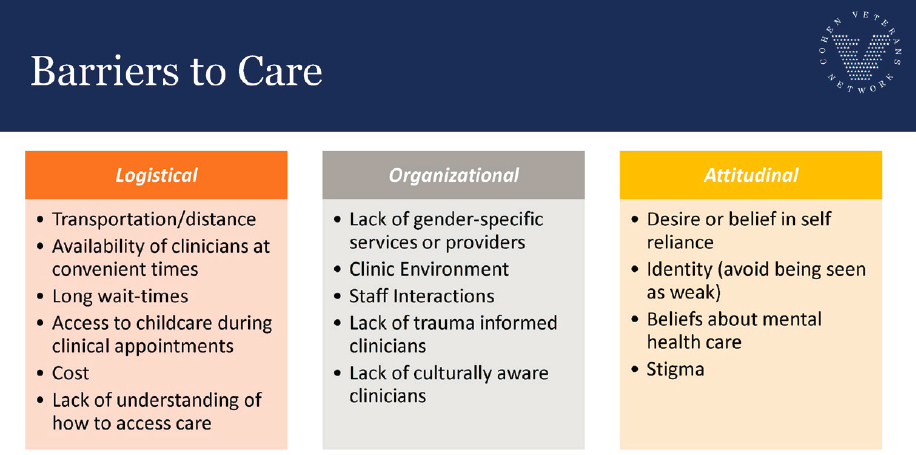

Next, she reviewed several barriers that keep veterans from accessing needed care, ranging from logistical to organizational to attitudinal (see Figure 2-1). Transportation and distance can be very challenging, especially given the need to take time from work and drive both ways for in-person appointments. This is further complicated by long wait times for and the need for child care during appointments. Another barrier is cost, she added. Wait times can be up to 6 months for a provider through TRICARE insurance off-base, but if veterans find a therapist who does not take TRICARE, the cost out of pocket can be up to $250 per session.

Neal-Walden shared access mitigation strategies that the network uses to address some of these barriers, including a triage and initial screening to prioritize an individual’s needs. It also offers a psychoeducational group for veterans who may not need specialized therapy but could benefit from additional support, stress management, or parenting techniques. To help manage stress and worry, it developed a cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) online tool with support from Blue Star Families.3 Additional strategies include case management to connect veterans to social services, clinical groups to provide effective treatment (e.g., CBT for insomnia, stress and resiliency groups), and fellows and interns to mitigate the provider shortage.

SOURCES: Tracy Neal-Walden presentation, April 20, 2023; Cohen Veterans Network.

___________________

3 Blue Star Families refers to a network founded by military spouses to provide a support network to military families. See https://bluestarfam.org/about/ (accessed August 1, 2023).

She shared Cohen Veterans Network data on telehealth clients. Looking at PHQ-9,4 GAD,5 and PCL-M6 scores, telehealth services produced improved outcomes compared to face-to-face services for clinically meaningful change and remission in depression, generalized anxiety, and PTSD, and increased retention rates in care.

Last, Neal-Walden emphasized the importance of offering comprehensive and holistic mental health care. During active duty, she pointed out, service members can easily access a chaplain, find help with financial services, and access physical fitness opportunities and other resources to help with overall well-being. But when they transition to veteran status, they often lose that supportive community. Although some of these elements may go beyond the scope of what VA can provide, partnering with community groups can allow for expanded access to available resources that can improve overall well-being.

DOVETAIL LANDING

Alana Centilli, president of Dovetail Landing and former fellow of the Elizabeth Dole Foundation, began with a video detailing her son Daniel’s story of coping with PTSD, a traumatic brain injury, a brain tumor, and difficulties after his time in the U.S. Marine Corps. After many mental health struggles, Daniel died in his sleep from his brain injuries. She recounted the numerous young male and female veterans she is connected with who battle their own demons and struggle to prosper in the civilian world. Although the care and support her family received from the Birmingham, Alabama VA hospital was very helpful, one of her biggest challenges was communicating with the clinicians providing treatment. Daniel was actively hallucinating, she noted, but because he was an adult in his mid-20s, his clinical team often did not consider her concerns even though she was his primary caregiver and observed his behavior on a daily basis. They also seldom considered how his behavior was affecting their entire family, and she emphasized that because caregivers

___________________

4 Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ)-9 is a tool used for screening, diagnosing, and monitoring self-reported depression symptom severity and frequency. See https://www.apa.org/depression-guideline/patient-health-questionnaire.pdf (accessed August 1, 2023).

5 Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD)-7 is a tool used for screening, diagnosing, and monitoring generalized anxiety disorder using self-reported symptoms. See https://adaa.org/sites/default/files/GAD-7_Anxiety-updated_0.pdf (accessed August 1, 2023).

6 PTSD Checklist is a 20-item self-report measure that assesses symptoms of PTSD, with three versions for different patient populations: military (PCL-M), civilian, and specific. See https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/documents/APCLM.pdf (accessed August 1, 2023).

like herself and other family members spend so much of their time on their veteran family members, VA clinical teams should welcome their input more and permit them to participate more actively in treatment planning.

In 2019, a few years after Daniel passed away, Centilli and her family put together some thoughts and ideas of what they had learned and how they could help other families in a similar situation. Centilli said that accessing VA services can be overwhelming for some veterans. For example, sitting on hold on the phone for 30 minutes and being transferred multiple times was not reasonable for Daniel to manage on his own. Recognizing veterans like Daniel and their families need additional support, and with the support of local and county officials, the organizational concepts for veterans’ therapeutic community was born, eventually called “Dovetail Landing.” She shared a video with attendees outlining the concept and plans for the community, with 30 tiny homes, 25–30 family-sized homes, a chapel, a community center, computer labs, and headquarters. Depending on the level of need, veterans can participate for 90 days to up to 6 months, Centilli explained. The headquarters, named “Daniel’s House,” has direct contacts to the local VA and Social Security, offers caregiver support, and can assist in accessing GI bill benefits. She also shared that Dovetail Landing is planning a “skills bridge” program with several private businesses to help veterans transition successfully to the civilian world. The community will offer several therapeutic activities, such as fishing, biking, climbing, yoga, and even learning how to forage. Centilli stated that veterans train for years to become proficient warriors and deploy to combat to protect the United States. But once they return, they often just have weeks to transition to the civilian world. VA and others need to make this shift better and more sustainable, she added, so they can find the same worth they felt when serving our nation.

DISCUSSION

Michele Samorani, associate professor at Santa Clara University, moderated the discussion and asked each speaker to provide one key improvement that VA could implement that would address some of the concerns discussed in the presentations. Neal-Walden replied that VA should continue to work on developing community partnerships and ensuring that community resources receive reimbursement. Often, she said, veterans are referred to Cohen Veterans Network without VA community care network approval, and as the network provides services to veterans who lack coverage, it is important that it is properly reimbursed.

Thampi replied that he is quite concerned about the slow hiring process at some Veterans Integrated Service Networks—the regional systems of care within VA. Legislation can improve policy and be very valuable, he said, but

without doctors, nurses, or administrators in the locations where they are needed, it will not matter. From his conversations with multiple caregivers, veterans, or people trying to work at VA, he has heard that it can take up to 6 months to receive an official job offer after candidates complete the interview process and are told that VA would like to move forward with hiring. Therefore, VA is losing qualified candidates who believe in its mission, Thampi said, as people seeking employment cannot wait 6 months to get an official contract. Although this process may vary by network, he said that it is a concern that worries his organization and its members.

Centilli reiterated the importance of community involvement and called for people to help in their own communities. She suggested that linking with VA services or offering available resources where possible can make it easier for VA to do its job.

This page intentionally left blank.