Multimodal Biomarkers for Central Nervous System Disorders: Development, Validation, and Clinical Integration: Proceedings of a Workshop (2023)

Chapter: 6 Regulatory Decision Making

Valentina Mantua emphasized the need to hear from a wide range of perspectives on regulatory guidance, barriers, and implications for clinical utility of multimodal biomarkers. Several workshop participants reflected on some of the challenges and approaches that might be considered throughout multimodal biomarker development to ensure that they are successful in the regulatory and payor decision-making processes.

BUILDING CONSORTIA FOR THE DEVELOPMENT OF MULTIMODAL BIOMARKERS

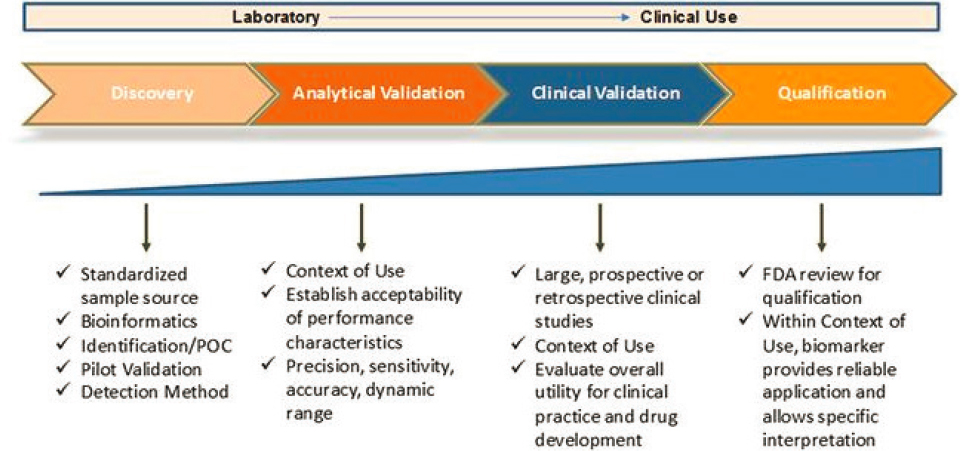

Terina Martinez, Executive Director of Critical Path for Rare Neurodegenerative Diseases at the Critical Path Institute, emphasized that “it takes a village” to bring together stakeholders to advance drug development tools, including biomarkers. In addressing drug development challenges, it is important to learn lessons from other disease areas and to look for common frameworks; leverage available resources and collaborations; consider many types of biomarkers; and iteratively evaluate what is being measured and what the data are showing; and engage with regulators early and often in this process. The evidentiary burden for a biomarker increases as it moves from discovery to analytical validation to clinical validation and ultimately to qualification (NINDS, 2023) (Figure 6-1). As it does, Martinez said, the amount of data will increase, and it is important to revisit and refine the context of use as those data are evaluated. The Critical Path consortium approach is being applied to a wide range of disorders, both rare and common, but all of them have a common theme of using multimodal biomarkers to inform staging of disease (Kinnunen et al., 2021; Tabrizi et al., 2022). Martinez said that there may be opportunities for multimodal biomarkers particularly in the early stages of these diseases (e.g., Alzheimer’s disease [AD], Huntington’s disease [HD], Parkinson’s disease [PD], and ataxias).

SOURCE: Presented by Terina Martinez on March 14, 2023; adapted from NINDS, 2023.

DECISION MAKING AMONG REGULATORS AND PAYORS

There is a “translational divide” in moving biomarkers used for research into clinical practice, said Chris Leptak, Executive Vice President of Drug and Biological Products at Greenleaf Health. “Whether you’re a regulator, a developer, or an academic, it’s always important to link the biomarker to its measurement method and to its context of use.” Regulators will also look at reproducibility across populations, adequacy of the analytic device, and feasibility of its use in both the clinical trial setting and as part of patient care as appropriate. For drug development, biomarkers will be evaluated alongside the method of measure, endpoint, and patient population, and each of these elements can be optimized. Validation of a biomarker will depend on its context of use and the potential benefits and risks associated with its use. “If you can’t define why you’re introducing a biomarker, you probably shouldn’t be doing it,” said Leptak. Furthermore, if a biomarker is fit for purpose in one study, it does not mean that it could be used in another.

There are several pitfalls to avoid when developing biomarkers for drug development, including inadequate planning and engagement with the Food and Drug Administration (FDA); ignoring the need for rigorous validation of measurement methods; over-interpreting of data from peer-reviewed publications, which may not be reproducible; and failing to recognize the importance of data management, including developing standard operating procedures and rigorous documentation. For multimodal biomarkers, many

approaches to validation can be successful. However, Leptak advised that it can be helpful to narrow down a multimodal biomarker approach to fewer elements to ensure that small milestones can be reached. During the discussion, he emphasized that multimodal biomarkers for drug development may include multiple types of measures but would be integrated into a single context of use.

Luca Pani, professor of pharmacology at the University of Modena and Reggio Emilia and Clinical Psychiatry at the University of Miami emphasized the critical importance of biomarkers usage in patient care by payors. Pani highlighted what he identified as a transformative point in regulatory thinking. This was characterized by a remark from former FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb who, while discussing specific gene therapies, said, “For some of these products, there’s going to be some uncertainty, even at the time of approval” (FDA, 2018). In Pani’s interpretation, Gottlieb’s comment signaled a paradigm shift whereby aspects such as the duration of response could be increasingly determined by payors, not just by regulators. He also drew attention to the Joint Clinical Assessment, a novel regulatory approach in the European Union designed to unify drug effectiveness assessment by the collective contribution by regulators and payors. In Pani’s view, a biomarker that would benefit patients most effectively is one that demonstrates a connection to the drug’s mechanism of action, the progression of disease, and the cost-savings in healthcare.

TRANSDIAGNOSTIC MULTIMODAL BIOMARKERS: A NEW CONCEPTUALIZATION OF DISEASE

“The three-fold promise of biomarkers to understand disease, apply understanding to develop therapeutics, and improve clinical care . . . can only be realized if we begin to operate with an evolved conceptualization of disease,” said Bill Martin, Global Therapeutic Area Head of Neuroscience for Janssen Research & Development. He pointed to the progress that has been made in AD, including in the identification of biomarkers specific to the disease that could be developed as efficacy measures and surrogate endpoints (Hansson et al., 2022). In contrast, for neuropsychiatric disorders, disease-specific biomarkers have not been identified; instead, there is genetic overlap between diseases (Lotan et al., 2014), symptomatic overlap between diseases, and comorbidity as the rule, not the exception. According to Martin, the field needs to shift its thinking from only trying to understand the disease as a single entity to identifying the multimodal biomarkers that have predictive and prognostic value for diseases, which may exist within a spectrum.

Martin said that there are key regulatory challenges for multimodal biomarkers, including identifying a single context of use, which regulatory

path to take in early drug development, uncertainty about the evidentiary burden for qualification, a lack of harmonization internationally, and how to distinguish multimodal biomarkers for neuropsychiatric disorders from behavioral measures. Moving forward, he said, it will be important for the field to begin to establish AD biomarkers as surrogate endpoints; identify biological subtypes or predictive markers for depression and schizophrenia; and begin longitudinal, transdiagnostic patient cohorts with multimodal biomarkers to begin to understand the course of disease and relationships between symptoms and biomarkers.

Martien Kas, a professor of behavioral neuroscience at the Groningen Institute for Evolutionary Life Sciences at the University of Groningen, provided a European perspective on development of transdiagnostic multimodal biomarkers. He said that the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) has been helpful for clinical practice and management of mental health disorders, but that something has to change for advancing the underlying science and for identifying useful biomarkers. He described the Psychiatric Ratings using Intermediate Stratified Markers (PRISM) project, which uses a precision psychiatry approach that is transdiagnostic and focuses on quantitative biological measures for social and cognitive deficits in AD, schizophrenia, and depression, regardless of the patient’s initial diagnosis (Kas et al., 2019). The project focuses on four domains that are affected across these disorders, including sensory processing, social dysfunction, cognition, and attention, and it uses a range of data (including electroencephalogram [EEG], imaging, and digital behavioral monitoring) to find quantitative links. For example, Kas said, they found that social dysfunction correlates transdiagnostically with default mode network connectivity (derived from brain imaging) (Saris et al., 2022). More recently, the project has worked to develop and validate a digital endpoint for social functioning that statistically differentiates between patients and controls and links to the imaging data. Kas emphasized the need for collaboration and synergistic expertise across sectors to make progress in these domains; the PRISM project includes 23 public and private partners from eight European countries.

There are several challenges for the development of these types of biomarkers, according to Kas, including transdiagnostic tools do not fit well within the regulatory system that focuses on the DSM-5 classification system; how to validate new quantitative multimodal biomarkers against the considered “ground truth” that is usually based on patient report through availability for defining primary endpoints for transdiagnostic domains (e.g., social functioning); and how to detect treatment effects when there are no specific treatments for these transdiagnostic domains.

In the workshop discussion, there was some conversation about how to define a context of use for transdiagnostic biomarkers. Leptak said that the context of use can be defined based on how the biomarker is used in

different populations, but that data will be needed to justify the use of the biomarker for each patient population. Mantua added that if a specific application is validated, then it will be important to identify the context in which it is validated.

MULTIMODAL BIOMARKERS AND EXPLANABILITY

Challenges for development of multimodal biomarkers are particularly acute for CNS disorders. Mantua said that wide constructs such as cognition could be challenging to define. More complex traits, such as social function or those measured based on machine learning models, will be even more difficult to define, validate, and use in drug development or clinical trials. Martin and Kas emphasized that it will be important that multimodal biomarkers, including those developed for transdiagnostic use, are explainable. According to Kas, the PRISM project focused on social function because it is a critical goal for patients and their families; to build a meaningful multimodal biomarker for social function, they have worked to link digital tools and imaging data to clinical social function scales. A key challenge, he said, was in identifying the ground truth for measuring social function.