Multimodal Biomarkers for Central Nervous System Disorders: Development, Validation, and Clinical Integration: Proceedings of a Workshop (2023)

Chapter: 7 Exploring Opportunities to Move Forward

The workshop highlighted many challenges and opportunities for the development of multimodal biomarkers for central nervous system (CNS) disorders. A final discussion aimed to identify potential next steps to overcome these challenges and maximize the opportunities of these biomarkers. Additional opportunities that were suggested by individuals in previous sessions are outlined in Box 7-1.

VALUE OF MULTIMODAL BIOMARKERS

Rebecca Edelmayer, Senior Director of Scientific Engagement at the Alzheimer’s Association, provided a patient advocacy perspective and said that early detection and accurate diagnosis for CNS disorders not only are medically important, but also provide emotional benefits for patients and empower them to make informed decisions. She said that it is important that those developing multimodal biomarkers are very clear about their context of use, including for communication with patients and the public about scientific progress (e.g., toward blood biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease [AD]). Edelmayer said that unimodal biomarkers could be layered into multimodal biomarkers and that it will be important to ensure that each addition adds value; this is the path that will lead us toward more precision medicine for CNS disorders.

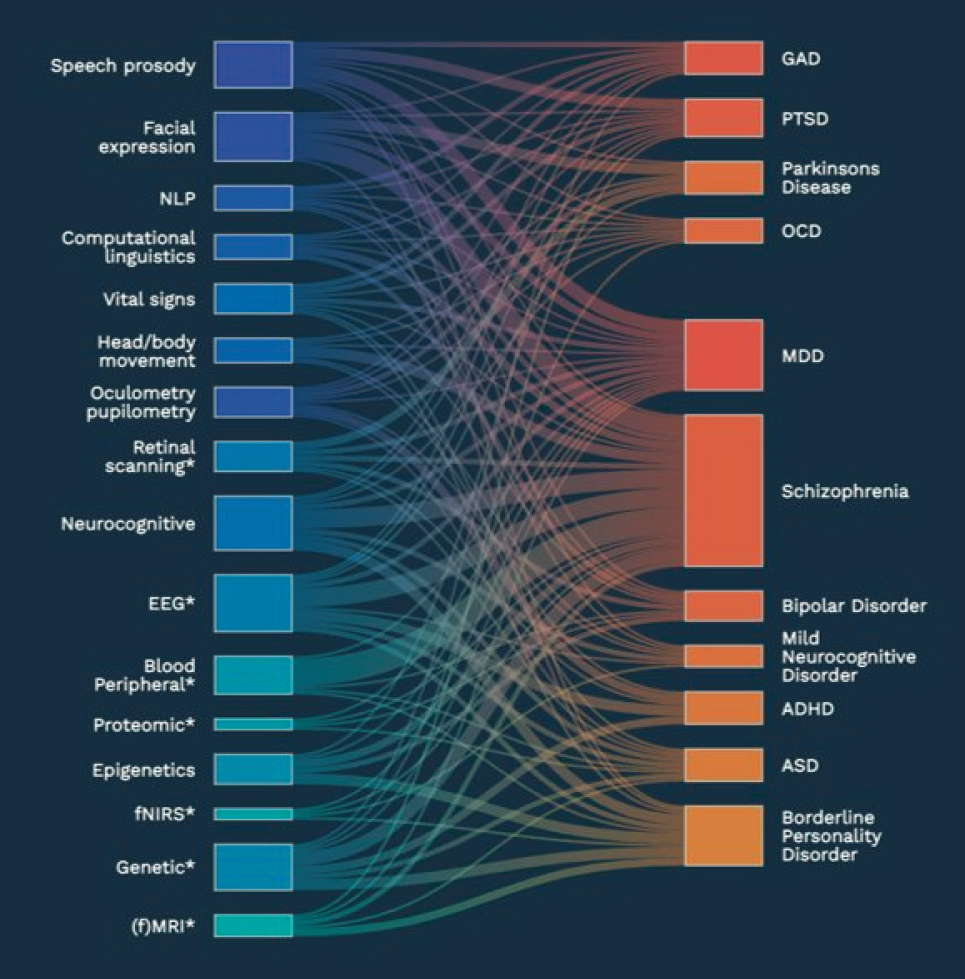

Multimodal biomarkers may enable us to better detect, predict, and monitor CNS disorders. Marc Aafjes, CEO of Deliberate.ai, described the need for multimodal biomarkers, pointing out that there are a range of biomarkers that are linked with CNS disorders, but these links are complex, and multimodal approaches are lacking (Figure 7-1). He showed a machine learning approach that integrates CNS biomarkers and may be able to predict clinical outcomes more accurately than clinical raters.

Drug development could also benefit from multimodal biomarkers. A key obstacle for drug development, according to Arthur Simen, Executive Medical Director at Takeda, is the high rate of failure for new drugs. He said that, for neurological disorders, “there is less than a 6 percent chance that a new molecule that enters Phase 1 will be approved.” The costs are also very high: “a new AD drug requires $5.7B when all costs are included

NOTE: ADHD = attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, ASD = autism spectrum disorder, EEG = electroencephalogram, fMRI = functional magnetic resonance imaging, fNIRS = functional near-infrared spectroscopy, GAD = generalized anxiety disorder, MDD = major depressive disorder, NLP = natural language processing, OCD = obsessive-compulsive disorder, PTSD = post-traumatic stress disorder.

SOURCE: Presented by Marc Aafjes, March 14, 2023. Used with permission from Deliberate.AI.

and 13.3 years of time.” Multimodal biomarkers have the potential to significantly reduce these development costs by providing “off-ramps,” allowing companies to determine more quickly when a drug candidate is likely to fail and saving resources for more promising therapies.

IMPORTANCE OF DATA AND COLLABORATION

“All of the presentations…and all the panel discussions have highlighted the great potential that we’re going to have with these multimodal biomarkers, but they have also highlighted the work that needs to be done and the challenges,” said Alessio Travaglia, Director of Neuroscience at the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (FNIH). He emphasized the need for collaboration to get the amount of high-quality, standardized data that will be needed to establish and validate new multimodal biomarkers for AD and other CNS disorders. “There is no single organization or researcher that can do this alone. . . it takes a village,” he said. By including researchers, clinicians, industry partners, and patient representatives, “we can move forward to the clinic, cutting costs, sharing resources, saving time, and building trust in the community.” As an example of successful collaboration, Travaglia pointed to the FNIH Biomarkers Consortium, which works to develop and qualify biomarkers, including those for CNS disorders.

For machine learning approaches, access to data is particularly important. Aafjes expressed the need for industry consortia to generate these data, optimally with support from the National Institutes of Health for this purpose. Guidance would also be helpful, particularly on how to standardize data acquisition and best practices for meeting the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) evidentiary requirements.

Simen echoed the need for extensive data to support the development and validation of multimodal biomarkers, including replication of studies in independent cohorts by independent investigators. He stressed the importance of collecting data on multimodal biomarkers alongside multiple clinical endpoints to provide additional context and utility for different outcomes, and that resources for analytics are also needed. He emphasized the need for collaboration and data sharing: “We really need to work together across boundaries between public and private institutions so that we can generate the quantity and quality of data that we really need to validate biomarkers and use them effectively in our trials.”

CLINICAL INTEGRATION OF MULTIMODAL BIOMARKERS

Edelmayer said that clinical trials and validation for biomarkers is just the beginning and engagement with communities and clinicians for real-world data collection will be important. ALZ-NET (Alzheimer’s Network for Treatment and Diagnosis), an FDA-recommended registry to track clinical outcomes for novel AD treatments, including diagnostics and biomarkers, is one example of such ongoing data collection. She also discussed a need for training and guidance for clinical use of multimodal biomarkers.

Elias Sotirchos, an assistant professor of neurology at Johns Hopkins University, also believes that clinical integration will be a key challenge for these biomarkers. He provided the example of blood tests for neurofilament light chain, a non-specific brain injury biomarker (Khalil et al., 2018). He said that interpretation of these blood tests varies widely depending on which clinical reference population is used for the analysis (e.g., Benkert et al., 2022; Bornhorst et al., 2022; Fitzgerald et al., 2022; Simrén et al., 2022; Sotirchos et al., 2023; Vermunt et al., 2022). He also noted that different assays for neurofilament light chain could differ in substantive ways (e.g., because they are antibody-based assays, they could detect different post-translational modifications).

Several workshop participants pointed out that the AD community has developed useful standards for the clinical use of biomarkers. Edelmayer cited the Global Biomarker Standardization Consortium1 that helps to develop reference methods and materials as well as guidance for sample collection and handling and appropriate use. To date, this group has been primarily focused on cerebral spinal fluid and blood/plasma analytes.

ACCESSIBILITY AND COST

Accessibility was described as a key challenge for multimodal biomarkers, and Edelmayer said that many of the benefits of multimodal biomarkers would depend on them being low cost, low burden, and non-invasive. She urged those developing multimodal biomarkers to think intentionally and proactively to pursue approaches that are most accessible. Simen agreed, saying that the field needs to get better at developing biomarkers that do not increase the burden on patients. He added that it will be critical to ensure that studies draw from representative populations that accurately reflect the intended patient population; ideally, these studies would be longitudinal and include patients that are pre-symptomatic or very early in disease progression.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Vikas Sharma summarized several cross-cutting points made throughout the workshop, including the opportunities and challenges of multimodal biomarkers for CNS disorders and the need for standardization, data sharing, and collaboration. Drawing on remarks from Travaglia, Simen, and other speakers throughout the workshop, he highlighted the need to collaborate and work across boundaries between academia and industry.

___________________

1 To learn more about the Global Biomarker Standardization Consortium, see here: https://www.alz.org/research/for_researchers/partnerships/gbsc (accessed April 28, 2023).

He emphasized the need for investment, particularly in the early stages of biomarker development and validation, and said, “we from the industry side . . . are willing to do this heavy lifting.” Linda Brady underscored the need for continued dialog across the community and looked forward to additional opportunities for engagement on these issues.