Measuring Law Enforcement Suicide: Challenges and Opportunities: Proceedings of a Workshop (2023)

Chapter: 2 Primary Sources for Measuring Suicide - Federal Data Sets

2

Primary Sources for Measuring Suicide—Federal Data Sets

Currently, several federal agencies measure suicide using varied methods of data collection. This chapter first discusses sources of data collected directly from law enforcement, which are primarily nascent, and then covers recent additions and innovations to data sources in public health, where suicide has been measured longer. A panel discussed these primary data sets and responded to questions and comments from the virtual audience.

LAW ENFORCEMENT DATA SOURCES

There are two federal data collections underway at two federal law enforcement agencies. Congress mandated the Federal Bureau of Investigation to establish a new data collection that is underway and discussed in detail as the first primary data source. The second law enforcement data source described is an internal data collection that was launched in 2023 by the Department of Homeland Security.

Federal Bureau of Investigation

Lora Klingensmith (Federal Bureau of Investigation [FBI]) stated that the FBI’s Law Enforcement Suicide Data Collection (LESDC) is statutorily mandated by the Law Enforcement Suicide Data Collection Act (LESDC Act; 2020), which was signed into law on June 16, 2020. The purpose of this legislation was to establish a new data collection to better understand and prevent suicides among current and former law enforcement officers at the federal, state, local, and tribal levels. The LESDC was implemented

on January 1, 2022; it collects data from organizations that voluntarily report suicide attempts or completed suicides by law enforcement officers. The LESDC Act defined law enforcement officers as including corrections, telecommunications, and judicial system employees (e.g., prosecutors and judges), even though this term is typically reserved for sworn officers (see Box 2-1).

While working to establish the LESDC, Klingensmith commented, “It would have been easier to identify all first responders and any employee under the umbrella of a law enforcement agency, such as a program and management analyst.” Although LESDC training is focused narrowly on the occupations defined in the law, she stated that suicides by employees other than those defined in the legislation have been reported. As a result, the LESDC has been set up to collect any incident reported; FBI staff reconcile these data after they are received to be consistent with the legislation.

The definitions for terms used in the Act were refined by the FBI using a task force composed of a diverse group of psychologists and professionals from across the nation to understand standards in different parts of the country. For example, the LESDC excludes suicidal gestures and ideation from the definition of suicidal behavior. Additional information collected by the LESDC includes:

- circumstances and events that occurred before each suicide or suicide attempt;

- general location of each suicide or suicide attempt;

- demographic information of each law enforcement officer who commits suicide or attempts suicide;

- occupational category—including criminal investigator, corrections officer, line-of-duty officer, 911 dispatch operator—of each law enforcement officer who commits or attempts suicide; and

- method used in each suicide or attempted suicide.

This information is only authorized to be obtained from a law enforcement agency; confidentiality protection was required in the legislation. Klingensmith underscored that personally identifiable information is not collected with the demographic information to maintain privacy and to avoid resistance from law enforcement agencies. Privacy is especially important because the information collected is subject to provisions in the Freedom of Information Act. The LESDC also collects information on the wellness resources available at each submitting agency or office.

Pretesting was conducted with 25 agencies representing different demographic groups. The three phases of testing were cognitive interviews, coverage assessment, and usability testing. The LESDC includes a preliminary worksheet with five sections to ease navigation and completion. Once someone has gathered the necessary information, data entry is estimated to take 10 minutes or less. Klingensmith noted that more challenges have arisen in accessing the secure platform than in entering the data. Once law enforcement agency personnel obtain authorization and access, they provide data to the FBI through the Law Enforcement Enterprise Portal. Quarterly training is provided via a webinar or at conferences if requested.

Reporting suicides and suicide attempts to the FBI through the LESDC is voluntary. As a result, law enforcement agencies want to know “what is in for me?” Klingensmith conveyed that agencies report these data to gain access to resources for their personnel and guidance in identifying the right resources. She emphasized that effective interventions can save officers’ lives and safeguard agencies from the devastating effects of suicide. Klingensmith stated that the FBI wants to ensure that the data will be useful in making policy and procedure decisions, and in identifying the resources that law enforcement agencies are lacking. In the first year of data collection, 22 agencies reported 32 suicides and nine suicide attempts. The average age of a person committing suicide was 43; the average age of someone attempting suicide was 30.

Department of Homeland Security

Anthony Arita (Department of Homeland Security [DHS]) shared that a new data collection in DHS was launched in 2023—the Suicide Mitigation and Risk Reduction Tracking (SMARRT) System. Arita noted that DHS is the largest law enforcement agency in the United States, with more than 80,000 law enforcement personnel distributed across these components:

- U.S. Secret Service

- Immigration and Customs Enforcement

- U.S. Customs and Border Protection

- Transportation Security Administration’s Federal Air Marshals Service

- U.S. Coast Guard

Arita explained that, as an occupation, law enforcement comes with elements that contribute to suicide risk, including (a) stress and burnout, (b) trauma and secondary trauma, (c) moral distress and moral injury, (d) maladaptive coping (e.g., alcohol and substance abuse), and (e) barriers to care and engagement. “Every suicide is tragic and raises the question of what we could have done different (or better) to prevent (or intervene) to preserve the precious lives of those who have dedicated so much on our behalf.” DHS leadership recognized that it did not have the data or intelligence to provide insights into risks and factors that underlie suicide; nor was it clear how to tailor a more effective response. Each of the component agencies had varied approaches, if any at all, to measuring suicide within its ranks.

In October 2020, the first suicide prevention policy in DHS was established, which required its component agencies to report suicides. The impetus for change was the need to standardize methods for collecting data about suicidal behavior. The SMARRT System helps by standardizing data collection, and thereby improving reliability and data quality and promoting data-driven prevention, intervention, and postvention strategies. Arita hopes the SMARRT System will encourage greater awareness and normalization of suicide prevention efforts. This standardized approach aims to reinforce a collective and unified effort to reduce suicides.

Arita went on to say that SMARRT is an internal system built on a secure SharePoint site with an interface to the DHS human resources (HR) department, which receives biweekly feeds from the National Finance Center (NFC) for DHS employees who died during the previous two weeks. The NFC receives an Office of Personnel Management Nature of Action code that issues stoppage of payroll payment to an individual. This code prompts an alert in the SMARRT System and initiates a new record. Arita commented that this is a helpful way to know that a death has occurred, and he commended his HR colleagues for their commitment to this approach to create a reliable system.

The next step is for a SMARRT program manager to email the decedent’s supervisor with a secure link to the SMARRT System to address the manner of death. If it was a suicide, the supervisor receives additional questions about the employee’s background and circumstances of death (Table 2-1). Because supervisors are not likely to be prepared to answer all

TABLE 2-1 Data Elements Collected in the Suicide Mitigation and Risk Reduction Tracking System

| Subject Area | Variables/Data Elements |

|---|---|

| Personal | Age, sex, race, ethnicity, education, veteran status, LEO status |

| Occupational | Agency, location, job series, pay grade, position, job length, duty status, performance, disciplinary issues, shift work |

| Event | Date/time, location, method used, alcohol/substance use |

| Family | Marital status, living arrangement, minor children |

| Mental Health | Conditions, stressors (relationship, finances, losses, legal, burnout, trauma), past SI/SA, trauma exposure |

| Medical | Injuries or illnesses impacting work or career, TBI |

| Alcohol/Drugs | History of use, previous problems, recent use |

| Legal | Disciplinary action, facing criminal charges, under investigation |

| Resources | Previous treatment, EAP, connectedness, problem-solving skills |

NOTES: EAP = employee assistance program; LEO = law enforcement officer; SA = suicide attempt; SI = suicidal ideation; TBI = traumatic brain injury.

SOURCE: Taken from Anthony Arita presentation, April 25, 2023.

questions after the initial request, several aids help them populate SMARRT for this record of a death, including:

- a training video that emphasizes sensitivity and accuracy of data versus expediency;

- a data sheet to download and guide data collection;

- follow-up upon survey completion; and

- suicide postvention support.

Among the occupational variables, 23 provide personal demographics collected when an employee is hired and are automatically populated by HR systems. HR data also include a federal job series code and include the war era in the case of a veteran. Arita indicated additional data sources that will be pursued, including elements from the National Death Index (NDI), death certificate data, and potentially the National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS). These are ways to corroborate what the supervisor reports as the cause and circumstances of death.

DHS is currently engaged in a department-wide effort to identify the foremost psychological health and resilience challenges law enforcement officers face, in order to develop a research strategy to better inform and understand efforts to address mental health. Another initiative is developing a periodic anonymous survey to establish baseline prevalence of

psychological symptoms, self-care practices, and other health habits. Arita noted that the Health Related Behaviors Survey at the Department of Defense (DOD) serves as a model for measuring the health, well-being, and psychological readiness of its workforce. He concluded by stating, “My hope is that DHS and other law enforcement agencies can embrace and adopt this measurement-based approach to supply our insights and inform our way forward to support, promote, and strengthen the psychological health of our workforce and prevent suicides.”

Perspectives on Federal Law Enforcement Data Sources

After the two primary data collections in law enforcement were presented by speakers from the FBI and DHS, a series of discussion followed. Several perspectives were offered including from the lens of policing, corrections, and law enforcement research. This section concludes with questions and comments posed by the virtual audience.

Policing Practitioner Perspective

Megan Amaturo (International Association of Chiefs of Police [IACP]) explained, “We know police officers are at an increased risk to suicide.” Routine stressors, combined with the stigma associated with mental health, impact help-seeking behaviors. She emphasized that more information is needed about suicide deaths and attempts, specifically in the policing profession.

Data and research are critical for identifying the scope of the suicide problem and monitoring the effects of wellness and suicide prevention programs. Amaturo observed that surveillance allows for data collection, and that research and evaluation are key to assessing effectiveness. She commented that very few research studies have focused specifically on police or other safety professions, and a lot of the existing literature among police officers has focused on job-related factors.

Strengthening data collection and program evaluation will allow police agencies to provide suicide prevention services. Additionally, findings will contribute to the base of what works to prevent suicide among officers. Amaturo noted that law enforcement agencies are increasingly adopting practices aimed at preventing suicide, such as peer support and traumatic incident response. However, these efforts often are not formally evaluated because of several challenges, including lack of funding or expertise, ethical concerns, and confidentiality.

Amaturo identified that one hurdle to reporting suicide is agencies’ hesitancy, based in the stigma that is still associated with mental health in the profession and fears that reporting will tarnish the agency’s reputation.

Amaturo said that a debate remains as to whether reporting will be mandated or remain voluntary; she also pointed out that many agencies experience legal and bureaucratic challenges with reporting to the FBI. Another concern is that reporting may violate a family’s wishes. Amaturo underscored the importance of engaging active law enforcement for candid conversations about how to address these concerns and shift the culture around suicide. She stated that the goal at IACP, in collaboration with the National Consortium on Preventing Law Enforcement Suicide, is to use these data to focus on improving prevention and intervention efforts.

Correctional Practitioner Perspective

Sarah Gillespie (Bureau of Prisons [BOP]) commented, “Data is only as good as the methods we use to collect it.” BOP has been collecting information about correction officer suicides since about 1997, but 18 months ago it began postvention programming in the field; Gillespie said these efforts are giving BOP a good idea about the factors that contribute to correctional officer suicide.

Approximately 4–6 weeks after a correctional officer suicide, Gillespie related, staff from BOP’s employee assistance program (EAP) and peer-support team go on-site. During these visits, EAP talk with staff on every shift. They talk to supervisors, coworkers, families, friends, enemies, and anyone who is willing to speak with them. BOP also has an objective third-party organization conduct focus groups to explore attitudes toward mental health, resilience, and health seeking. The focus of these visits is to provide support and facilitate healing, although other concerns may rise to the top. Gillespie said, “We will hear from the spouse who discloses intrapersonal violence that no one knew about at work or an Army buddy that knew about traumas.” Now that they are conducting postvention visits, Gillespie has explored the route of psychological autopsies1 for a more structured and formalized approach to data collection. She believes psychological autopsies would be a useful tool for BOP.

Gillespie observed that the picture painted during postvention interviews is very different from the one painted during phone calls only. One of the things she likes about the LESDC is that it includes some of the relevant complexities, such as being looked over for a promotion or relationship stress. She noted that the FBI put a lot of resources into developing this collection (and participated in its development), so she wants to ensure that BOP as a reporting agency enters the most accurate and complete data possible.

___________________

1 A psychological autopsy helps to reconstruct the proximate and distal contributing factors of an individual’s death by suicide... or left undetermined by a medical examiner or coroner. (see https://suicidology.org/pact/)

Law Enforcement Researcher Perspective

Jack McDevitt (Northeastern University) noted that a broad array of people is trying to measure law enforcement or correctional officer suicide, and important lessons can be learned from other national measurement efforts. He echoed a comment by Alexis Piquero (Bureau of Justice Statistics [BJS]) that it is going to take time to get this right. In 1990, McDevitt was part of a group that developed the first national-level data collection with the FBI to measure hate crimes. “Nationally, we did not have any measures at all at that point,” he said. Both of these efforts require the ongoing ability to update data and continual refinement over time. Another challenge McDevitt raised is the reality that some police suicides will not be reported because they may not be acknowledged. Hate crimes are again a useful example: people do not acknowledge why they are attacked. Another example is arson, which can take weeks and months to investigate. As a result, the measurement must be flexible enough to collect data when not everything is not known during the initial reporting of an incident, with the ability to update as more information becomes available.

As McDevitt explained, current research shows that rates of suicide are similar across sizes of agencies. Therefore, the kinds of data collection systems required must account for law enforcement agencies that vary by expertise, experience, and resources. McDevitt illustrated this by commenting on a recent study in Maine that collected data about traffic stops. A couple of the large agencies said researchers needed to “get the data electronically and into the cruisers,” while some of the agencies did not have mobile display terminals. McDevitt emphasized creating a system that can work for all law enforcement agencies across the United States.

McDevitt observed that there will always be tension between a standardized data collection system—in which everybody is getting the same data from the same sources to compare across agencies—and a tailored data collection system for gathering detailed information on every incident. He commented, “It is important to understand that this does not need to be a choice, and we can do multiple things at once.” He explained that there can be a standardized system that presents a baseline across all law enforcement agencies, and agencies can also drill down to multiple sources to understand those situations. McDevitt concluded by remarking that these measurement approaches are important for officers—police, sheriff, probation, corrections, judges, etc.—who see only one way out in challenging situations. “The goal is to design a data collection system, but it is ultimately to save lives.”

Discussion with Planning Committee and Audience

Planning committee co-chair Vickie M. Mays (University of California, Los Angeles) asked Gillespie about how feasible the postvention interview process is and whether it can be standardized. Gillespie acknowledged that this in-depth approach depends on an agency’s size and noted that BOP has 122 institutions and six regions nationwide, and more than 35,000 employees. She explained that she (as director of the EAP) has been doing visits; while it is an exhausting travel schedule sometimes, she thinks it is doable for individual agencies. Comparing when BOP did not do postvention interviews versus the current approach, she stated that the data her team receives now are more complex and have contributed to greater understanding of the contributing factors for suicide: “I cannot imagine going back to only using telephone calls.” She also explained that mission change has now come to the forefront as they continue to visit institutions. When an institution experiences a mission change of some kind, many of these institutions also have a suicide not too long afterwards. Gillespie stated she is talking to people about what was so hard about the mission change and what made the work so hard; this contributes to the EAP’s ability to provide feedback to the agency about change management and how to mitigate the risk for stress and burnout, and, in some cases, suicide.

Mays asked about federal suppression rules—especially for gender, age, and race and ethnicity—because suicide is a rare event. Klingensmith stated that there are no restrictions outside of the “rule of ten” that applies to their other data collections, but she noted that the FBI will work with its privacy attorneys. McDevitt drew from experience with federal hate crime data, where gender identity is a category that is collected. He pointed out the complication that, while the federal government will collect these data, some states will not report it: “You might have provisions at the federal level, but you may have states that are not participating fully in the process, and that is governed by state rules and bodies that make it more complex.” Jimmy Baldea (Los Angeles Police Department [LAPD] Vital Signs Monitoring Program) asked whether mechanisms are in place for existing agency wellness programs to offer suggestions or recommendations on strategies to the FBI or DHS. He noted that his program with the LAPD collects daily vital signs that might be useful to federal law enforcement agencies. Klingensmith explained that this type of information is managed by the FBI’s HR department, which has a central unit for establishing these policies and procedures. She conveyed that there has been interest in these approaches for a few years and invited Baldea to contact her via email to connect him with the appropriate parties in the FBI.

Phillip Stevenson (Congressional Research Service) remarked on the parallel McDevitt drew with this new suicide collection to the evolution of

FBI’s hate crime data collection. Stevenson noted that one of the frustrations users have with the hate crime data is the number of nonreporting agencies. He asked what the FBI is doing to reduce nonreporting across its data collections for hate crime, officers killed and assaulted, and the use of force. Klingensmith stated, “There are various ways the FBI is working with state programs and federal partners—including BJA [Bureau of Justice Assistance] and BJS—on each of these different data collections in different ways.”

Planning committee member Janice Iwama (American University) summarized several comments audience members raised regarding the recent legislation allowing death benefits for suicide and concern about “incentivizing” suicide. Amaturo emphasized that IACP hears this concern repeatedly. She provided context about Public Safety Officer Benefits including that the benefit allocation must meet specific criteria, including time constraints, types of traumatic events, and debilitation by post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Amaturo observed that very few people currently know about these benefits.

PUBLIC HEALTH DATA SOURCES

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has a number of data collections to measure suicide. Christopher Jones (CDC) is director of the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (NCIPC); he offered three questions to consider regarding suicide measurement: (1) How could the data quality in the systems already in place be improved?, (2) What factors result in misclassification?, and (3) What new analytic techniques can improve understanding of the data on suicide?

Mortality data collected in the United States provide important insights into the challenges in understanding suicide mortality. The National Vital Statistics System at the CDC is the official tabulation of mortality data in the United States based on death certificates from medical examiners, coroners, and other death certifiers. The NVDRS is broader, collecting more detailed information from death certificates and law enforcement reports.

As Jones noted, it is fundamentally important to recognize that there are several thousand medical examiners and coroners across the country, who have different structures and procedures. Some areas have forensic pathologists with certifications; other areas have elected officials who oversee the death certification process. Jones posited that this variation in methods for certifying deaths contributes to challenges in gathering the level of evidence required by a medical examiner or coroner to classify something as a suicide versus an unintentional overdose or injury.

Jones underscored that the context of the post-COVID environment is important: while the medical examiner and coroner system was already

burdened, it worsened over the past 3 years. There are not enough resources nor sufficient investments to support new technologies for improving classification across the country. Jones stated that extra staff could collect additional data to provide insight on manner, cause of death, occupations of decedents, or other contextual factors that may be important for suicide prevention.

The NCIPC has been interested in misclassification because some deaths that are suicides might be coded as undetermined or unintentional injuries, especially when these deaths go to a coroner or death certifier without a note or clear evidence of intent to harm. As a result, the burden of suicide is underestimated.

With respect to new analytic techniques, Jones explained that there are ways to use natural language processing and machine learning to extract disparate or unstructured data from narratives, in order to mitigate the misclassification problem. However, these methods are still new and need to be refined. Jones also described missing data as another data quality issue. There is variation in the capture of race, ethnicity, and occupation—as well as varying definitions. Other factors that might contribute to suicide risk that are not captured well include data from emergency departments and emergency medical systems.

Jones highlighted ways in which the CDC and the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) are addressing these challenges. The CDC and NCHS created an office for medical examiners and coroners within the past couple of years as a centralized hub for engaging with these death investigators to work through issues and understand what supports are needed to improve their work. More broadly, for several years, a federal medicolegal death investigation work group—co-chaired by the CDC and the National Institute of Justice—has brought together agencies to share information about current efforts to improve the workforce; think about technology, resources, and supports; and understand the challenges medical examiners and coroners face. This has been a particularly fruitful cross-government collaboration for understanding the landscape and identifying some challenges.

Jones noted the emergence of social media, or syndromic data, that can be used for monitoring suicide and factors associated with suicide: “Certainly we know nontraditional data sources tend to be timelier than some of our public health sources.” Jones discussed blending data sources to better understand real-time suicide trends. These blended data were originally published at the national level and combined emergency department data calls to the suicide-prevention lifeline and poison centers; variation in economic indicators; and posts on sites such as Reddit, Twitter, and Tumblr. Jones asserted that blending those statistics with machine learning does a good job predicting trends. There is additional

work now to determine whether this same precision is possible at a lower geographic level or whether additional data sources are needed.

Electronic health records (EHRs), containing both structured and unstructured data sets, present another opportunity to explore. Jones wondered how artificial intelligence, machine learning, and natural language processing can help make sense of these data. Although not all data desired would be available in an EHR, some variables could be linked from other data sources to provide a more comprehensive and holistic perspective. Jones explained that typically not everything is available in a given data set, but data linkage—merging data with administrative records on occupations, criminal justice involvement, substance use treatment, mental health treatment, education, and other social determinants of health—is promising. These data can also be linked to health claims data and then back to mortality data (e.g., NDI) to provide a much broader perspective of what had been going on with someone before they die. Jones noted that some new work has been done with Medicare- and NDI-linked data to understand the touchpoints and risk factors that could remain undetected when looking at only one data set.

National Violent Death Reporting System

Alina Arseniev-Koehler2 (University of California, San Diego, and Purdue University) explained that the NVDRS is a surveillance system for violent deaths in the United States. She explained the NVDRS defines a violent death as “resulting from the intentional use of physical force or power, whether it is actual or threatened, against oneself or another person, group, or community.” Each record is created by training public health workers at the state level, who use death certificates, law enforcement reports, coroner or medical examiner reports, toxicology tests, and other sources of information and then extract standardized variables about the circumstances of death. The NVDRS currently includes more than half a million records; suicides are the majority of these deaths (more than 300,000). Therefore, the NVDRS provides a large and rich source of information—with 600 possible variables for each death—for studying suicide.

The NVDRS began in 2002 when data were collected from six states; it expanded to all 50 states, Puerto Rico, and the District of Columbia in 2018 (see Table 2-2). Arseniev-Koehler asserted that this coverage means the data set is useful for studying both general patterns and geographic variation. In addition to the decedent’s demographics, the NVDRS collects their current occupation (at time of death), as well as usual or longest-held occupation. She noted that these occupational fields are of particular

___________________

2 Coauthors are Vickie M. Mays and Susan D. Cochran.

TABLE 2-2 States Added to the National Violent Death Reporting System by Year

| Year | U.S. Statesa |

|---|---|

| 2002 | MA, MD, NJ, OR, SC, VA |

| 2003 | AK, CO, GA, NC, OK, RI, WI |

| 2004 | KY, NM, UT |

| 2009 | MI, OH |

| 2014 | AZ, CT, HI, IA, IL, IN, KS, ME, MN, NH, NY, PA, VT, WA |

| 2016 | AL, CA, DE, DC, LA, MO, NE, NV, Puerto Rico, WV |

| 2018 | AR, FL, ID, MS, MT, ND, SD, TN, TX, WY |

aIncludes Puerto Rico and the District of Columbia.

SOURCES: Taken from Alina Arseniev-Koehler presentation, April 25, 2023; data from https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/nvdrs/NVDRS-Overview_factsheet.pdf

interest for the audience of this workshop because they allow researchers to analyze occupations even for decedents who were retired at their time of death. The NVDRS uses the Census Bureau’s industry and occupational codes for this classification, which include a lot of granularity (e.g., police officer, dispatcher, bailiff). Among the other variables are circumstances, including whether the decedent had a known mental health condition, received mental health treatment ever or at the time of death, or experienced a recent life crisis (e.g., divorce).

In 2022 additional variables were added using the Public Safety Officer Suicide (PSOS) module, which will be discussed in more detail later in this chapter. Arseniev-Koehler emphasized that the NVDRS has a lot of analytic capacity from the information available in the unstructured fields. She illustrated these unstructured data using an artificial summary of a coroner’s summary abstracted by a public health worker: “Victim is a 19-year-old white male who hung himself. He was being treated for depression and his parents and siblings thought he might be gay. He had not been doing well in classes lately and was upset about his grades. No other circumstances are known.”

Arseniev-Koehler underscored that these unstructured data are extremely useful in two ways. First, they can be used to extract information that is not present in the closed-ended variables. For example, while sexual orientation is not coded for all decedents in the close-ended variables, there is often information about sexual orientation in the unstructured data. Second, these summaries include latent topics. In her research with collaborators, she applied a machine learning approach called topic modeling to identify topics in the summaries. An example of a latent topic identified

TABLE 2-3 Latent Topics in the Summaries of Unstructured Data Using Machine Learning Methods

| Assigned Topic Label | Five Most Representative Terms of the Topic |

|---|---|

| Acting Strangely Lately | drinking_heavily, drinking_excessively, acting_strangely, exchanging_text_messages, acting_strange_lately |

| Everything Seemed Fine | fell_asleep, everything_seemed_fine, seemed_fine, wakes_up, ran_errands |

| Cleanliness | unkempt, messy, disorganized, cluttered, dirty |

| Drug-Related Cognitive Disturbances | groggy, lethargic, disoriented, incoherent, agitated |

| Somatic Symptoms | dizziness, nausea, headaches, fatigue, diarrhea |

| Escalation | becoming_increasingly, becoming_more, became_more, increasingly, noticeably |

SOURCES: Taken from Alina Arseniev-Koehler presentation, April 25, 2023; adapted from Arseniev-Koehler et al., 2022.

through this research is “acting strangely lately” (Table 2-3); this information is not reflected in the close-ended variables. Arseniev-Koehler emphasized that topic modeling is useful for discovering new patterns in the summaries and pointing to potential interventions. Lastly, she underscored that only data on completed suicides are in the NVDRS; it does not collect any information on suicide attempts.

Public Safety Officer Suicide Module of the National Violent Death Reporting System

Bridget Lyons (CDC) discussed the new PSOS module that has been added to the NVDRS. The PSOS module was funded through a congressional appropriation in fiscal year 2021 and was implemented in January 2022. The module was created in partnership with many stakeholder groups, including the IACP, National Sheriff’s Association, and federal agencies such as the U.S. Fire Administration and the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Although it builds upon the NVDRS infrastructure and tracks suicide among public safety officers, Lyons emphasized that no personal identifiable information is collected in NVDRS or the PSOS module.

The PSOS module provides insights into suicides under the broad definition set by Congress, which includes paid and volunteer work for a public safety organization. The module is divided into four sections (see Table 2-4). As an example, Lyons demonstrated how the role and pay status variables would capture whether the decedent was a volunteer firefighter. A report

TABLE 2-4 Sections and Selected Variables in the Public Safety Officer Suicide Module to the NVDRS

| Section | Selected Variables |

|---|---|

| Victim | Agency type Role (occupation) Pay status Active or retired |

| Work Environment |

History of chronic or acute traumatic work-related event Timing and/or onset of most recent chronic or acute traumatic work-related event Type of chronic or acute work-related event (text field)Work-related stressors Referred to EAP or work-provided mental health |

| Injury Details | Where injury occurred (expanded from core NVDRS) Duty status at the time of suicide (on duty, off duty, other) Decedent affected by chronic or acute work-related injury/disability |

| Weapon Information | Firearm was work-issued or service weapon |

NOTES: EAP = employee assistance program; NVDRS = National Violent Death Reporting System.

SOURCE: Taken from Bridget Lyons presentation, April 25, 2023.

from the first year of data from the PSOS module should be available in the fall of 2024. Lyons noted that NVDRS staff who work on PSOS are continuing to work with several federal partners and state abstractor colleagues who submit data to the NVDRS. Lastly, although the PSOS module currently does not have a policy for researcher access to a restricted data center, plans are in place for establishing some type of protected access, with details forthcoming.

Research Applications Using the National Violent Death Reporting System

Bernice A. Pescosolido (Indiana University Bloomington) discussed research traditions that span disciplines when trying to measure suicide: one is to use rates and the other is to look at individual cases. Each of these traditions brings limitations. Using rates is impacted by ecological fallacy; for example, using unemployment rates does not necessarily mean that those who are unemployed are the persons taking their lives. However, findings from individual case studies using health claims, hospital, or school data may not be generalizable.

Pescosolido explained that geography does have an effect; she used an example of how social determinants of health are impacted by the neighborhood where someone lives. This lack of being able to understand the individual in context has implications for prevention and treatment. Thus,

she discussed her research on suicide risk based on where a person lives, and specifically on connectedness.

Problem of the Zeros

Pescosolido noted that, while it is easy to get data on people who take their lives, identifying the appropriate comparison group is more difficult. Generally, this comparison would be people who took their lives versus those who did not. This leads to what Pescosolido refers to as the “problem of the zeros” (0 = did not commit suicide; 1 = committed suicide). She stated there are data on social and neighborhood characteristics from death certificates, but this type of information is not available on a granular level for people who are still alive. However, self-reported suicide attempts or ideation can be measured with surveys or extensive questionnaires and can be connected to area data using the American Community Survey (ACS).

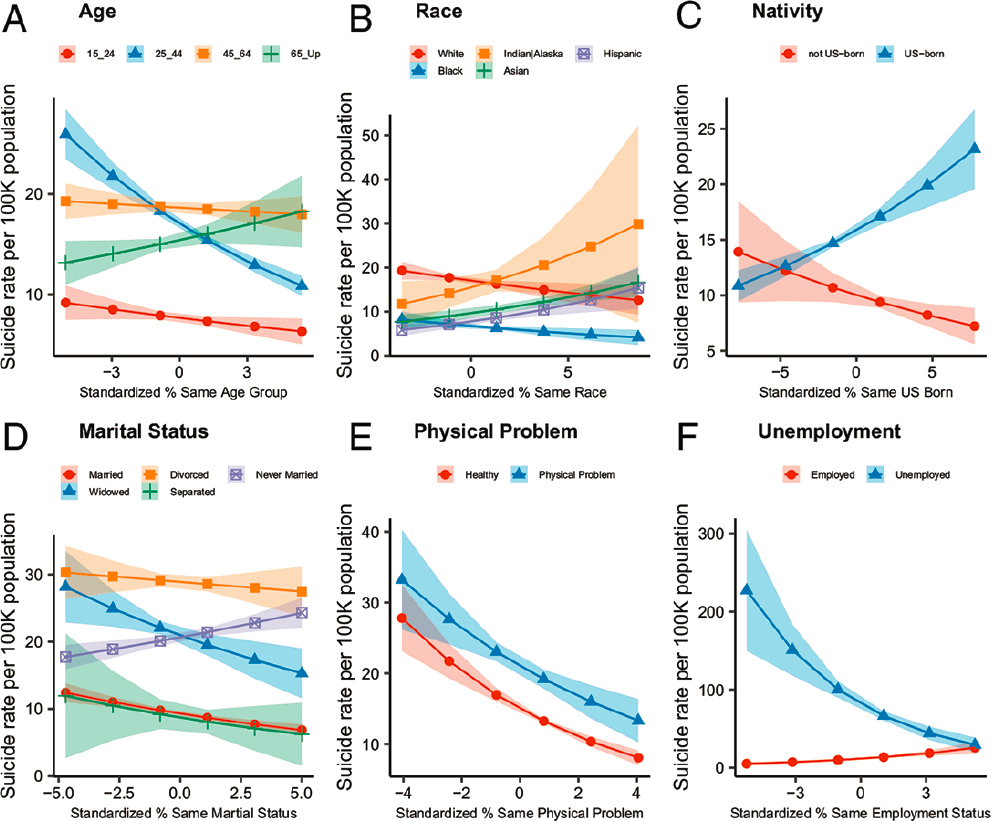

Pescosolido and her colleagues used logistic regression analysis for the binary outcome of death by suicide (Pescosolido et al., 2020). They merged NVDRS data with ACS to examine the individual and contextual factors that predict risk of suicide while controlling for other factors (Table 2-5). This new data set also enabled analysis of homophily—one’s tendency to make network ties with people who are like oneself—by creating an index to operationalize connectedness as cross-level sociodemographic homogeneity, or “sameness.” This approach using NVDRS and ACS linked data showed whether people lived near people most like them or least like them.

The coauthoring team also examined the correlates for suicide using this merged data set (Figure 2-1; Pescosolido et al., 2020). Pescosolido

TABLE 2-5 Data Elements Used to Compare Suicides and Nonsuicides

| Suicide “Ones” | Nonsuicide “Zeros” |

|---|---|

| NVDRS | ACS |

| All counties, 17 states | All counties, 2005–present |

| Treatment for mental health and toxicology screen | N/A |

| Proxies: intimate partner problem/marital status, job/school/financial problems | Marital status, migration status |

| Age, occupation, gender, veteran status, suicide history, crisis in the past two weeks, mode, date | Age, occupation, gender, income |

| Current depressed mood, current MH problem, diagnosis | Physical/mental/emotional problems |

NOTES: ACS = American Community Survey; MH = mental health; N/A = not available; NVDRS = National Violent Death Reporting System.

SOURCE: Taken from Bernice A. Pescosolido presentation, April 25, 2023.

SOURCES: Taken from Bernice Pescosolido presentation, April 25, 2023; Pescosolido et al., 2020.

explained that her team found a dramatic difference in the risk of suicide for an individual who experiences unemployment depending on the context where they live. She illustrated this using an example of Detroit, Michigan, which has high unemployment but low suicide rates, versus Greenwich, Connecticut, which has low unemployment but high suicide rates. Isolation of these different groups is not the same for all marginalized groups. The risk of suicide is reduced for both White and Black people if they live in an area with a substantial number of people from their same racial group; however, this homogeneity for Asians and Native Americans actually heightens the probability of suicide.

Federal Occupational Injury and Death Data Sources

Hope Tiesman (National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health [NIOSH]) discussed occupational data and their role in measuring law

enforcement suicide. She emphasized how important occupational coding is for measuring the size of the problem, in order to focus on how to address law enforcement suicide. Tiesman explained, “While coding who is a law enforcement officer may seem straightforward, there are many nuances to consider ... even though most researchers believe that the measurement of an occupation is free from error.”

Determining whether a decedent was a law enforcement officer using occupational coding can be difficult, Tiesman continued. The process begins with a coroner or medical examiner asking the next of kin what the decedent did for a living; NIOSH provides guidance on how to do this (Robinson et al., 2021). The description is then directly added to or paraphrased on a death certificate. Traditionally, this was done by trained coders with extensive knowledge of occupations and titles, but more recently it is performed using computerized coding programs.

Various data sets capture occupational codes intended to classify similar jobs, in order to understand exposures to industry hazards. Tiesman explained that after these codes are assigned they are used to determine whether a decedent was a law enforcement officer. Examples of narrative descriptions of law enforcement officers include:

- “she worked for the Austin PD”

- police officer

- Lt. Sgt. Patrol Division

- public safety officer

- cop

- dog warden

These descriptions are then coded into different occupational coding systems.

Tiesman indicated that the two most common coding systems are the Bureau of Labor Statistics’s Standard Occupational Codes—33-0000 Protective Service Occupations, 33-3000 Law Enforcement Workers, or 33-3050 Police Officers—or the Bureau of Census Codes—3700 Protective Service Occupations or 3850 Police and Sheriff Patrol Officers. From these codes, a researcher must select which are relevant for how they are defining law enforcement officer (Table 2-6).

Tiesman juxtaposed the LESDC definition of law enforcement officer with the NVDRS definition of public safety officer. The FBI uses a legal definition, whereas the CDC uses a definition from the public safety realm. Despite these varied definitions, classification is purely subjective, so a police cadet might be included even though they are not yet a sworn officer.

| Database | Source | Occupation Definition | Maintained | Recent Year | Occupational System |

| CFOI | Various sourcesa | What were they doing for work at time of death? | BLS | 2021 | SOC |

| NOMS | Death certificate | Usual occupation | NIOSH | 2020 | BOC |

| NVDRS | Death certificate | Usual occupation | NCIPC | 2020 | SOC |

adeath certificates, autopsy reports, law enforcement reports, family/friend interviews.

NOTES: BLS = Bureau of Labor Statistics; BOC = Bureau of Census Codes; CFOI = Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries; NCIPC = National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; NIOSH = National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health; NOMS = National Occupational Mortality Surveillance; NVDRS = National Violent Death Reporting System; SOC = Standard Occupational Codes.

SOURCE: Taken from Hope Tiesman presentation, April 25, 2023.

| law enforcement officer | FBI’s LESDC: Any current or former officer (including a correctional officer), agent, or employee of the U.S., a state, Indian tribe, or political subdivision of a state authorized by law to engage in or supervise the prevention, detection, investigation, or prosecution of any violation of the criminal laws of the U.S., a state, Indian tribe, or political subdivision of a state. |

| public safety officer | CDC’s NVDRS: All local, state, federal, military, and tribal law enforcement officers, parole/probation officers, officers of the court, firefighters, emergency medical service clinicians, and public safety telecommunicators. |

Tiesman concluded by identifying reasons why occupations may be listed incorrectly on a death certificate: inaccurate reporting by family/friends, retirement, or work in other occupations. In the case of retirement, this is often impacted by the recency of retirement. Although “usual occupation” is the guidance, the longer someone is retired or perhaps takes an additional job, the less likely that an occupational code for law enforcement officer will be assigned. Tiesman also urged that it is important to move toward a universal definition for the purposes of suicide research.

Discussion of Public Health Data Sources

Mays noted that there is interest in working with these data sets in a Federal Statistical Research Data Center where they can be joined; she asked whether there are unique identifiers to merge the files. As Lyons explained, linkage with the NVDRS would have to be done at the state level because the data do not contain personal identifiable information when they are submitted to the CDC. However, the CDC is partnering with the Veterans Health Administration to link NVDRS data on suicides with DOD Suicide Event Report data; a similar data-sharing arrangement could possibly be reached within the federal government and expanded to the FBI and DHS.

An audience member inquired about which machine learning methods are used and their degree of accuracy. Arseniev-Koehler responded that traditional topic modeling methods can be applied to the data, but their success is impeded by the extensive use of jargon in the NVDRS summary data. As a result, she and her colleagues have developed a new form of topic modeling for the NVDRS summary data that may be generalizable to other data sources, such as clinical notes.

Jennifer Myers (Education Development Center) asked whether there has been any consideration of comparing cultures that are collective versus individualistic. Pescosolido responded that many communities are concentrated by race and ethnicity, which is how she and her colleagues operationalized “sameness.”

Planning committee co-chair Joel Greenhouse (Carnegie Mellon University) asked Pescosolido about combining data at an individual level with survey data at higher level. She explained that, for her work, she uses geographic codes (i.e., Federal Information Processing Series codes), which are frequently at the county level. The linkage process can take many years.

Planning committee member Natasha Frost (Northeastern University) asked Lyons how much of a narrative is available in the PSOS module. Lyons explained that the same narrative from the NVDRS is included in the PSOS. She also noted that the PSOS module includes guidance for the state abstractors, so there may be more precise narratives supplied for public safety officers and suicides. In the PSOS module itself, some of the fields include free text.

Planning committee member John Violanti (University at Buffalo) asked whether there was any way to standardize the variables across some of these data sets. Pescosolido observed that when data are combined, one often has to use the lowest common denominator to harmonize data elements. However, some new techniques—that have not been available with traditional imputation—use machine learning to impute data.

An extensive discussion about the complexity and different types of occupational codes followed. Mays asked whether there could be a standard

classification for occupational codes. Tiesman stated that the NVDRS uses occupational information provided on the death certificate, which is then coded by the CDC into the NIOSH Industry and Occupational Computerized Coding System and into Standard Occupation Codes. The difficulty is that these systems are different. Arita stated that the SMARRT System uses the federal employees’ job classification series, so it could likely be recoded into the other occupational codes. Arita observed that there would be great utility in aggregating across data sets.

Elijah Morgan (Institute for Intergovernmental Research) commented on how many different data collections systems exist in law enforcement—federal, state, and local—and asked whether an effort has been made to integrate and streamline these systems. Klingensmith noted that the different law enforcement data collections have received some type of funding from Congress, and for the LESDC, the FBI worked with its legal team to align the data collection elements with the legislation. While the PSOS module had a broader definition, Klingensmith explained, “We are all restricted to the pieces of legislation to which we are beholden.”

An audience member asked whether any of these systems collect information on alcohol use or blood alcohol content at the time of death? Lyons responded that the NVDRS collects alcohol use, toxicology, whether a substance caused the death, and information on mental health and substance abuse treatment.

PRIMARY DATA SETS DISCUSSION

To stimulate a discussion about the primary federal data sets used in measuring law enforcement suicide, Greenhouse moderated a panel discussion and observed that this was likely the first time all these different approaches had been brought together. He characterized the discussion as an opportunity to compare and contrast these data collections. He invited the panelists—Mays, Iwama, Violanti, and Jeffrey L. Sedgwick (Justice Research and Statistics Association)—to share highlights that emerged once all these collections were considered together.

Violanti was impressed by how rich the data are, and he observed that there is much promise in machine learning for analyzing the qualitative data. He stated that this is especially important for understanding what factors contribute to suicide. Violanti stated that, while he has used the NVDRS data, their restriction to fatal data is limiting and misses suicide attempts, which are critical to understand.

Sedgwick offered observations from his current position but also from the lens of a former director of BJS (the workshop’s sponsoring federal statistical agency). One of the important points that was not raised but is relevant to this discussion is how much heterogeneity there is across law

enforcement agencies in the United States. He explained that there are more than 18,000 law enforcement agencies, and they range in size from one part-time officer to highly professionalized organizations in major cities. In addition to the size of the agencies, Sedgwick observed that there is also heterogeneity in the way the data are handled and reported in public safety/criminal justice, public health, and the military. All of these sectors have different cultures around handling data.

Sedgwick said that he often explains three ways people think about quantitative information: “numbers, data, and statistics.” These all have different characteristics and impact how they can be used and combined, and what counts as being reportable. He underscored a point raised earlier by McDevitt that a high degree of patience is required when working on these problems and with these data sets that are so complex.

Iwama observed that a number of data sources offer the opportunity to study the size and scope of suicide, but they each have limitations and concerns, particularly following recent changes in law enforcement. For example, it is important to understand how groups are impacted differentially across race, ethnicity, and gender following efforts by law enforcement to increase diversity in their recruitment efforts. Regarding retention rates, several large departments have experienced resignations increasing by greater than 40 percent between 2020 and 2021, according to a survey by the Police Executive Research Forum (PERF). As a result, excluding officers who retired or resigned from the measurement of completed or attempted suicides could potentially eliminate a key source of information in understanding this problem and creating prevention programs.

Iwama also raised the point that, while quantitative data are important, qualitative data can provide key insights. Greenhouse concurred about the value of qualitative data, and he reminded the audience of Gillespie’s earlier remarks about the value of going out to the field and talking to supervisors after suicides.

Mays noted that she is also trained as a clinical psychologist. She commented that she was both excited and frustrated by the amount of data and opportunities to build measures into newer data collections to make them complementary. She stated that the federal government often refers to a family of surveys that provide different slices of the same problem across the lifespan or within a particular context. Thus, Mays argues for harmonization over standardization. Mays suggested, “We need the bully pulpit of the surgeon general and chief statistician of the U.S. to provide big-picture view vision and strategic planning about this measurement.” She explained that her frustration is with Congress’ focus on the documentation of death, which provides a high bar for understanding correlates and prevention.

Greenhouse observed that three data collections—LESDC, the SMARRT System, and NVDRS’s PSOS module—have just started. He asked Mays

what could be done to harmonize these data sets in a way that would help the field. Mays responded that a possible next step could be a series of hearings and reports that occur in federal advisory committees or National Academies studies to make the whole greater than the sum of its parts. Sedgwick responded that findings in studies often are taken up to Capitol Hill but are then sent to a specialized committee or specialized hearing. As a result, the ways to connect criminal justice data with health data are obscured—criminal justice data are considered by the judiciary committees in the House and Senate, while health data are considered by the Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee in the Senate and the Education and the Workforce Committee in the House. Sedgwick stated, “A holistic view of data highly valued by researchers is antithetical to how Congress—and separation of powers—is structured and operates. Federalism further complicates this with local, state, and federal governments.”

Iwama suggested an alternative, bottom-up approach, since many law enforcement agencies are already collecting these data on their own. She said that keys for helping agencies use these data include guidance (especially for small agencies), funding, and technical assistance. Iwama emphasized that leadership buy-in is critical when so many agencies are already understaffed. She speculated whether funding could help shore up their resources so that providing LESDC data will not be viewed as burdensome.

Greenhouse reminded workshop participants that LESDC reporting will be voluntary and the SMARRT System data will come from supervisors. He asked what sort of incentives with the community could be used to increase participation rates. Mays responded that people are particularly concerned about trust and privacy, especially if this could result in an agency being sued. Violanti commented that law enforcement agencies have respondent fatigue and have received too many surveys, especially in the past year. He further speculated that the data provided to the FBI may be insufficient as times goes on because departments will be concerned that their leadership could be blamed or otherwise viewed as responsible for these suicides.

Sedgwick offered an example, citing the FBI’s transition to incident-based crime data. Officers have been trained to code incidents according to local statutes, but officers must now provide 84 incident characteristics for every call on a shift, significantly increasing the burden of a data collection and reporting. Additionally, not all agencies have mobile laptops in patrol cars, so officers will need to enter these data at the end of their shift. This is a reality check for researchers. How will the cost for the LESDC be defrayed to the law enforcement agencies?

Iwama added that, based on her experience working with racial profiling data, she believes the role of leadership buy-in cannot be underestimated. She argued that the importance of collecting data and how they will benefit officers must be explained. Moreover, having a chief explain

how law enforcement suicide has directly impacted them personally can result in higher reporting rates and understanding how important it is to provide data.

Greenhouse observed that the suicide data are mortality studies, so he questioned what the appropriate comparison groups are to study risk and protective factors. Violanti responded that comparisons with the general population are not helpful. The National Occupational Mortality Surveillance (NOMS) data are compared with that of other workers to control for unemployment. He added that the NOMS data are now available up through 2020. Violanti cautioned against comparing rates for suicides by firefighters, because the job is not the same. Comparing data with that of correctional officers could be used, but Violanti contends that “a corrections officer’s job is completely different than a police officer on the street.” Ultimately, these difficult decisions to identify the most appropriate comparison groups are up to the researcher.

Planning committee member Brandon del Pozo (Brown University) expanded on Violanti’s earlier observation that a police chief could feel exposed and not understand the benefits of reporting. He also echoed the comments raised by others about the importance of funding to facilitate this reporting. Sedgwick observed that this process will be a long journey, and law enforcement agencies should not be punished for not providing data but incentivized instead: “Show them how it is in their interest and how it will benefit them to report suicide data.” Violanti stated that most agencies have around 25 officers, so there is a high burden to report. Given the rise of lawsuits against chiefs generally, “you should have known there was a problem” becomes an impediment to reporting and making departments vulnerable.

Tia White (United Wellness & Safety Academy) stated that she has been looking for data on suicides or suicide attempts by law enforcement officers who were also military; she asked whether these data are being examined. Tiesman responded that NIOSH has a paper in peer review in which first responders were compared with all other worker groups in the NVDRS. She and her coauthors found that first responders who died by suicide were more likely to be veterans. However, Tiesman noted that first responders are also more likely to have past military experience compared with the general population. Mays also noted that, in her discussions with researchers preparing for this workshop, one topic raised was to consider job categories that identify police officers within the military.

Baldea asked whether there are mechanisms in place that fund labor or fraternal orders of police organizations to assist law enforcement agencies in reducing stigma, so more comprehensive data can be gathered. Frost noted that it is important to get buy-in from labor and union organizations when collecting these data in policing and corrections settings.

Arita underscored the impact of stigma that constrains participation in engagement with resources, resilience practices, and access to care, and that leadership buy-in is important. He noted several levels at which stigma is present: individual; social (e.g., fear of loss of confidence from leaders); and institutional, when policies are prejudicial against mental health conditions and treatment. Arita suggested that one way to reduce stigma is to improve psychological health literacy by explaining the symptoms and treatment options for mental health conditions and normalizing the experiences of grief, depression, and anxiety—and that “we can in fact grow from overcoming adversity.” He argued that making this part of the universal, human experience can go a long way to reduce stigma. Arita concluded by acknowledging that stigma impacts the quality and quantity of data available on mental health.

Tiesman shared that much can be learned from other occupations because it is rare to have strong, evidence-based workplace suicide prevention programs. However, she noted that a program for construction workers in Australia called the “Construction Working Minds” has been effective in reducing stigma. Construction workers have parallels to law enforcement in that both fields are male dominated and both countries have cultures of masculinity.

Pescosolido stated that most of her research has been on stigma, including a National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine consensus study (National Academies, 2016). She shared that there is a National Institutes of Health antistigma group, which may have resources available. Pescosolido stated, “I do not think the principles of changing stigma within law enforcement are different than what we have learned about how to do this because it is really about a few key principles like ‘Nothing About Us Without Us’ and having it tailored to the worksite.” She also shared research that found no difference in stigma in the health and medical professions from that in the general population.

An audience member asked about effective strategies for increasing buy-in from other agencies and granting access to their data in respective departments. del Pozo noted how significant it is to have stakeholder agencies, such as the IACP and PERF at this workshop, who can help communicate these messages to the more than 18,000 law enforcement agencies who are unlikely to attend scientific conferences. As will be discussed in Chapter 6, del Pozo emphasized the importance of having a current police chief speak at this workshop directly about the impact of suicide in an agency to bridge the human connection to data and measurement.

Theresa Patten (Christine Mirzayan science technology fellow) noted that, while individual privacy is critical, del Pozo’s point about leadership consequences when reporting a suicide event raises a question about group privacy (e.g., privacy for law enforcement agencies). Is there a process for

such group anonymization? Mays responded that data suppression occurs in areas such as public health whereby data are aggregated up to a level at which they cannot be identified. Moreover, this must be communicated at the outset when data are collected. Klingensmith echoed that this has been raised using an example of one department that had more than one suicide; she asked, “If you push this data out in 5 years, will my agency be identified as a ‘horrible’ department for someone to work?” One of the items in the LESDC pilot testing was to consider how to publish data, such as using small-, medium-, and large-sized agencies. Frost noted that, regardless of the unit of analysis, there are steps for deidentifying data, such as removing some of the attributes that are reported.